1

The Validation Spiral

I couldn't shake the feeling of precariousness—that all that I'd worked for could just disappear—or reconcile it with an idea that had surrounded me since I was a child: that if I just worked hard enough, everything would pan out.

—Anne Helen Petersen, Can't Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation7

“BINGO!” I HEARD my classmate call out. I started to feel my eyes well up with tears.

My second-grade teacher noticed. She guided me out of the classroom and into the hall. She gently asked why on earth I was crying over a game of bingo. As only a precocious 8-year-old could, I tried to explain that I hated bingo because it required no skill. It was pure luck. There was no strategy to employ, no natural talent to rely on to win. Either your numbers were called or they weren't. I couldn't extract value out of a win. There was no meaning to victory—although loss still hurt. My teacher gently explained that it was “just a game” and encouraged me to enjoy it. But that's the thing. There has been nothing in my life that has been “just a game.” Every win was a small indication that things would work out, that I'd be okay. Every loss was a devastating reminder that I could lose everything—and probably would.

What I couldn't quite explain at the time was that there was no way I could parlay a game of bingo into validation that I was good enough. Today, I know this feeling—this fear—well. It's with me all the time. I'm self-conscious to admit that this continues to be an issue for me. I'm much more aware of it now, and I course correct much more quickly. But in owning the fact that I still struggle, my hope is that this story (and this whole book, really) doesn't get thrown into the mountainous pile of stories of overcoming. I don't believe that we're supposed to transcend all of our challenges—congenital or cultural. I believe that recognizing the persistence of these challenges is key to maintaining our awareness as well as acting to collectively to make change. I constantly seek ways to prove myself good enough and validate my worthiness. I used to worry that I fixated on demonstrating that I was better than others, but I've come to realize that, instead, I'm just trying to prove that I belong. And that it's okay for me to take up space.

I seek validation of my worth, my usefulness, my value in everything. And I'm not alone. Validation-seeking is one of the defining pathologies of our culture. How could it not be? We move through social circles with the brand names we buy. We attempt to one-up each other by what we post on social media. We strive for more and better at work, at home, and at play. We're desperately seeking a way to figure out whether our numbers will get called or whether someone else is going to yell “BINGO!” long before we can cover up the squares.

The Question of Worthiness

Why is validation so elusive? Why do we organize our lives and work to prove to others (and ourselves) that we're worthy of love, respect, and belonging? Because we've been taught to question our worthiness. And while this isn't a new phenomenon, it gained a new flavor over the last century or so.

In 1947, a group of leaders in the fields of economics, sociology, and history gathered at a ski resort on Mont Pelerin in Switzerland. They were there to discuss what they saw as harmful overreach by the governments of Western Europe and the United States. That harmful overreach? It was government programs like Social Security and unemployment insurance as well as regulations on business and industry. Western democracies increasingly leaned toward democratic socialism, and this group was quite concerned. The Mont Pelerin Society, as the group would come to be known, advocates a hands-off approach to economic policy. The group believes that private enterprise and free markets can provide better solutions than governments. Its approach is in direct opposition to Keynesian economics and Marxist philosophy, and its aims would be familiar to anyone who consumes the smallest amount of political news in the United States.8

Friedrich Hayek was one of the organizers of this original conference. Hayek was an advocate for individualism and self-reliance over socialism or collectivism. He believed that free society—and free markets—would create better outcomes than one that was planned or designed for desired outcomes: “If left free, men will often achieve more than individual human reason could design or foresee.” Who is going to argue with liberty, am I right? As he started to draw conclusions about how to apply this philosophy, though, things got a little weird. In Individualism and Economic Order, Hayek writes:

…only because men are in fact unequal can we treat them equally. If all men were completely equal in their gifts and inclinations, we should have to treat them differently in order to achieve any sort of social organization. Fortunately, they are not equal; and it is only owing to this that the differentiation of functions need not be determined by the arbitrary decision of some organizing will but that, after creating formal equality of the rules applying in the same manner to all, we can leave each individual to find his own level. There is all the difference in the world between treating people equally and attempting to make them equal.9

What Hayek suggests here is that if everyone were equal, we'd need the state to determine our responsibilities—choose our occupations, determine our wages, maybe even select our homes or families. While dystopian novelists have long envisioned destructive systems in this vein and dictators like Stalin, Mao, and the Kim family put them into practice, it's hardly true of the direction Western democracies took in the early 20th century. Instead, those nations took steps to treat more people equally—white women finally got the right to vote, chattel slavery ended, and workers started to gain some protections and the right to collective bargaining.

Hayek, of course, worked at a time when the illusory veil of a monocultural nation had yet to be lifted. He was “free” to allow his arguments to pertain to the white, educated, property-owning upper class man. He was unburdened by the structural inequities faced by women, workers, former enslaved people, or immigrants. He could easily explain away their poverty, lack of rights, or lack of opportunities as a function of their “gifts and inclinations,” rather than a product of a system that favored people like him: “…the relative remunerations the individual can expect from the different uses of his abilities and resources correspond to the relative utility of the result of his efforts to others but also that these remunerations correspond to the objective results of his efforts rather than to their subjective merits.” Your economic conditions, then, are the product of your interests, talents, and value to society.

This, then, might be the genesis of our contemporary concern with worthiness and validation. Hayek and his buddies in the Mont Pelerin Society, including economist Milton Friedman, the figurehead of conservative economics in the United States, have had a profound and long-lasting effect on our cultural narrative. The authors of Confidence Culture, Shani Orgad and Rosalind Gill, described the cultural impact of this movement, known today as neoliberalism, as a “hegemonic, quotidian sensibility.” They argued that the machine Hayek set in motion transformed us into entrepreneurs-by-necessity, “hailed by rules that emphasize ambition, calculation, competition, self-optimization, and personal responsibility.”10

Anything less than the successful organization of your life around those factors is a personal failing, a deficit in your usefulness to society. You see the evidence of this in the hoops someone has to go through to apply for disability or even unemployment assistance. You see it in the “means testing” that gets baked into every piece of legislation designed to help people move out of poverty. It's baked into performance reviews, the gig-ification of the workforce, and stagnant wages. You even see it in the way different fields of study are treated at the college level. The department I graduated from was eliminated a couple of years ago in order to siphon its funding into a multimillion-dollar sports medicine and physical therapy building. The message? Sports medicine practitioners and physical therapists are worth more to society than philosophers and theologians. What's more, if you venture onto any social media platform, you can witness the performance of usefulness and worthiness to rake in those validating likes.

Maybe today, faced with a distinctly multicultural society and hard evidence of how free markets do not create level playing fields for people, Hayek might draw different conclusions. Maybe he would accept that privatization has exacerbated inequality and lack of freedom for many. But his work, along with others', in the first half of the 20th century fomented a whole movement which, in practice, has created a pathological fear of unworthiness aimed to keep us striving, consuming, and climbing over others on the way up the ladder. It's from within this movement that other questions of worthiness arise, most often around gender, disability, and race.

As a woman, I learned a host of shoulds and supposed-tos that would prove my worthiness. I should attain a body that conforms to white, straight Western beauty standards. I'm supposed to see my value in finding a husband and caring for a family. The after-effects of second-wave feminism conditioned me to measure myself against standards that are traditionally coded male so that I could prove I was worthy of being a 21st-century woman. Men deal with the question of worthiness, too. They're socialized to pursue becoming the “alpha” of their friend groups. They're taught to see their value in their ability to provide for a family financially or claim the sexiest mate. They're conditioned to measure their worthiness against their title at work or the car they drive. And, of course, that only begins to account for the social conditioning of nondisabled, cis-gendered, heterosexual, neurotypical people. When you add disability, nonconforming gender, queerness, immigrant status, or neurodivergence into the mix, the weight of the pressure to “measure up” can be too much to bear. Race adds a whole other element to account for.

Lucky for us, thanks to the legacy of individualism (which I'll explore more in Chapter 2), even the way we process our anxiety about worthiness has a pathology. We call it the “Imposter Syndrome,” the feeling that you are not good enough and soon to be found out as a fraud. This phenomenon was first described by Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Imes in 1978.11 Imposter Syndrome has most often been characterized as an individual condition—a mysterious questioning of ability despite all indicators to the contrary which disproportionately impacts high-achieving women. However, seeing Impostor Syndrome as an individual condition belies the very real, very loud messages that women and underestimated groups receive, telling them that, if we were really good enough, we'd already be doing better than we are.

It often feels like the only way to answer the question of worthiness is through external validation—and achieving bigger and better goals is one of our primary ways of doing that. In smaller ways, we also seek validation in our daily commitments and responsibilities. By saying “yes” to more and more, we can feel more useful and more worthy of the part we play in our families, our workplaces, and our communities. That is until it all starts to get too much, and we hurtle toward burnout. One of the ways we can see this cultural pattern most clearly is by how we overcommit and overschedule ourselves.

“I'm busy!”

We live in a chronically overcommitted culture. We say “yes” to too many things. We pack our calendars full of life and business commitments. We pin our hopes on doing it all. We're fried and frazzled from just trying to keep up with our commitments. We're stretched beyond our capacity. You'd think that the exhaustion and anxiety caused by this state of affairs would be enough for us to put an end to it. But very few of us reach that conclusion on our own because “saying yes” is one of the primary ways we seek the external validation that temporarily pacifies our inner struggle. Without all of the excess commitment and responsibility, we lose a crucial way to reassure ourselves that we're doing okay, that we're still productive members of society.

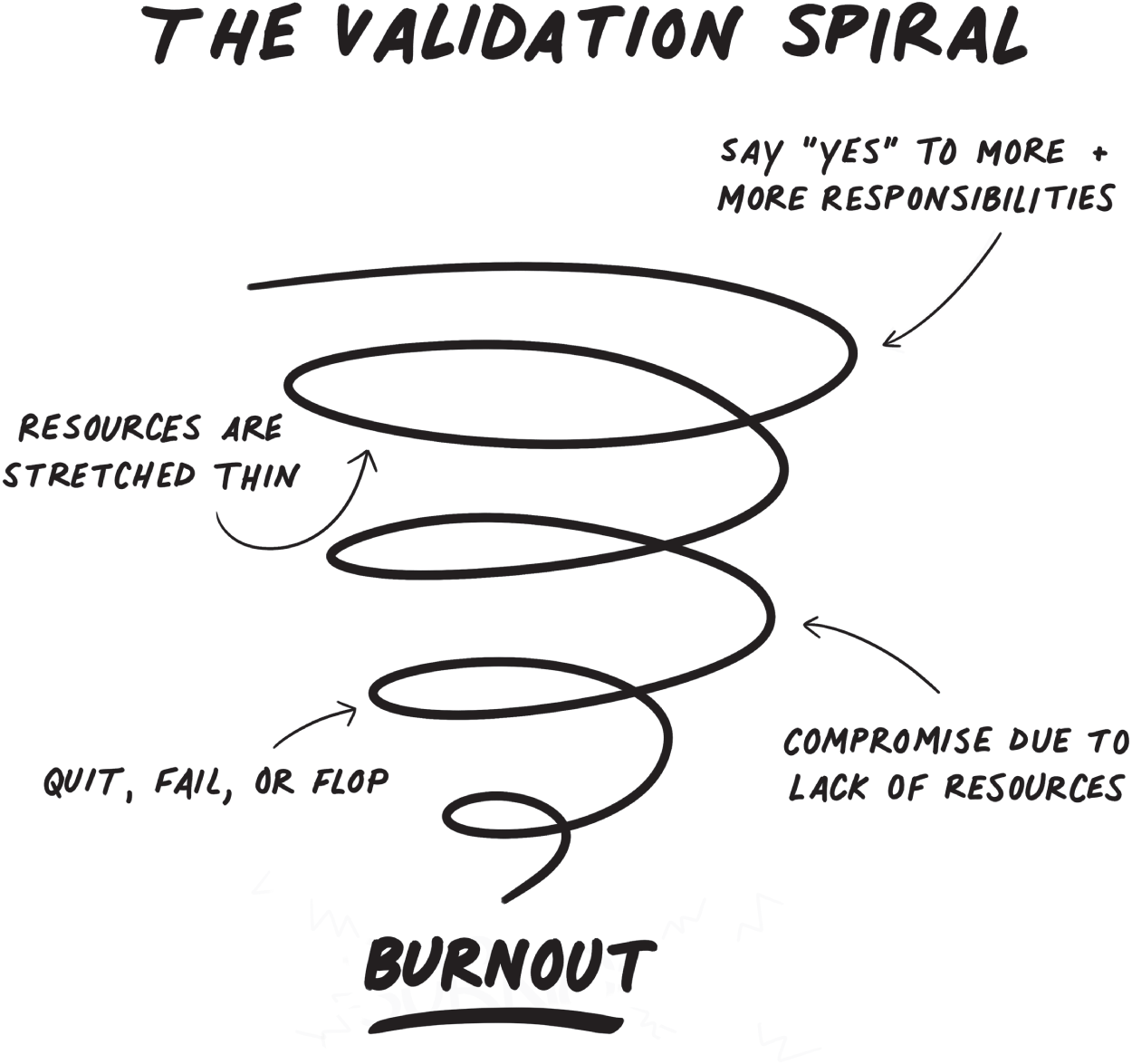

Our culture celebrates the entrepreneur who sleeps four hours per night and the single mom who works two jobs to keep food on the table. We're afraid to be seen as lazy, unproductive, or coasting. The more we say “yes” to, the more we can expect to be lauded for our efforts and validated in our contributions. Saying “yes” gives us another chance at hearing our number called in the bingo game of life. But, as I'm sure you've realized by now, this causes some problems—a phenomenon I call “The Validation Spiral.”

Dejà Vu All Over Again

The Validation Spiral starts in that all-too-familiar place: saying “yes” over and over again. It might sound like, “Yes, I'll bring the cookies to softball practice even though I'll be coming straight from work,” or “Yes, I'll head up another project outside of my job description,” or “Yes, I'll take on another client even though I'm already working 60 hours per week.” We seek validation for our worthiness and usefulness in our families, in our jobs, in our friendships, and even in the quiet moments we call “me time.” At first, the extra responsibilities and commitments seem harmless. The inconvenience or time feels like an appropriate trade-off for feeling helpful, like a valuable member of the team. Every time someone asks you to step up or help out, you feel like you belong.

But over time, those commitments start to add up. We fill our capacity to overflowing and stretch our resources thin. We might feel resentful of the people who have asked us for help or angry at ourselves for always saying “yes.” Despite the growing exhaustion and bad feelings, we push on. We struggle against labels like unhelpful, difficult, or lazy—labels we are all too quick to put on ourselves. We push on until we can't anymore. Maybe we get sick, or we relapse into a mental illness or addiction. Perhaps insomnia brings us to our knees. Maybe we end up burned out and unable to cope with all of the responsibilities.

Burnout, by the way, is a studied phenomenon, not simply a term for being stressed out and exhausted. Burnout is the result of overwhelming stress on the body—including the nervous system. The stress doesn't have to be overwhelming in terms of acute magnitude—a divorce, diagnosis, or job loss. The overwhelming stress that causes burnout is often an overwhelming accumulation of stress. In other words, all those yeses add up to psychological and physiological consequences. Herbert Freudenberger studied burnout among “caring professions” in the mid-1970s. He characterized the condition as emotional exhaustion, decreased sense of accomplishment, and depersonalization. Essentially, when we burn out, we've cared too much for too long, seen a lack of impact from our actions, and burned the empathy candle at both ends.12

Burnout is the more intense of two inevitable results of endless validation-seeking (the other being undercommitment, which I'll explain in the next section). We give and strive to prove our worthiness to others—and ourselves. We give and persevere until we're exhausted, ineffective, and resentful. In their book Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle, Drs. Emily and Amelia Nagoski describe how our bodies fight back against all of the stress we impose on ourselves while our fear of selfishness or laziness compels us to continue capitulating to new responsibilities. They write that our “instinct for self-preservation is battling a syndrome that insists that self-preservation is selfish, so your efforts to care for yourself might actually make things worse, activating even more punishment from the world or from yourself because how dare you?”

In our culture, women and marginalized people experience the imperative to overgive, overdeliver, and overcommit to the most significant degree. But no one is immune to the ways that uncertainty, complexity, and emotional labor can contribute to burning out. Journalist Anne Helen Petersen documents the universality of burnout among millennials in her book Can't Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation. Petersen's analysis feels spot-on to me—we're the same age—but it also resonates with many who were born before 1980. Burnout isn't some quirk of psychology in the 21st century. It's the product of a system that hasn't worked and won't work for anyone but the wealthiest and most powerful. Wage stagnation, unhealthy work expectations, precarious employment structures—not to mention the erosion of any assistance from the government if things go south—makes it difficult to feel a modicum of comfort, let alone attain success. Petersen writes, “The only way to make it all work is to employ relentless focus—to never, ever stop moving.”

Undercommitment

Most of us, I think, are familiar with the potential for burnout and its costs. We can recognize it in others and maybe even in ourselves. But burnout is just the more evident result of our quest to prove ourselves worthy and useful. The other way overcommitment and validation-seeking plays out is seemingly more banal, less deserving of intervention: undercommitment. While burnout may put us on the sidelines, undercommitment keeps us in the game but doesn't allow us to play our best. Undercommitment is what happens when we lack the necessary resources to carry out the responsibilities we've said “yes” to. When we've overcommitted ourselves on the whole, we're bound to be undercommitted to any individual endeavor. Opting to overcommit means opting out of the ability to be all-in on what you're committed to. We might think we're following through and holding up our commitments, but we also end up with disappointing results because we just couldn't invest the time or effort required for better results. I mean, what else could we expect? We had to parcel out our reserves of time and effort between the multitude of things we said “yes” to despite being overscheduled and exhausted already.

In my work with small business owners, I see the phenomenon of undercommitment all the time. The folks I work with are passionate, effective people. They care deeply about their work and the people they serve. But they worry that they're not doing enough, that what they've created isn't good enough, and that the businesses they've built aren't strong enough. So they push themselves to do more and more. They end up with highly complicated plans and overcrowded calendars. So they divide up their limited resources among all the things they think they're supposed to be doing to maintain the perception that they're doing this whole business thing right. The result? Everything they do is a half-measure: the social media posts, the sales calls, the product development. They don't get great results because they can't pursue anything they do with the proper resources. If you don't have the capacity or resources to devote to what you've committed to, whatever you're doing won't work, even if your plan is sound (more on capacity and resources in Chapter 5). Undercommitment can be difficult to identify while you're in it, though. And it can be tough to spot when the stakes are as high as they are when we're working through our responsibilities to business, career, or family. Instead, we internalize the results of undercommitment (e.g., lackluster results, missed opportunities, resentment) and use them as evidence of our own personal failings.

I first started to notice my undercommitment pattern outside of work or family. I noticed it in sports. I played a bunch of sports as a kid and early teen. In high school, I started to focus more on school and music to prepare for college, so sports took a (very) backseat. Two decades passed before I reacquainted myself with my inner athlete. It was love at second sight. I started running. Then I learned bouldering—which is climbing on short walls or big rocks with no ropes. From there, I started powerlifting and practicing yoga. Working out helped me deal with my anxiety, and training for new performance milestones gave me a sense of, you guessed it, validation.

I put a lot of time into fitness and sports. But even so, it was a challenge to effectively divide my resources among running, lifting, climbing, and yoga. At first, I tried to improve my performance in each discipline concurrently. Early on, this was possible—not because I was training effectively but simply because I was training instead of sitting on the couch. As time went on and my general performance improved, I found it more and more difficult to improve my performance in any individual pursuit. I tried to run faster, lift heavier, climb harder, and flow more gracefully all at the same time—failing miserably. I was always sore, constantly tired, and always on the verge of injury. Even though sports were a low-stakes venture for me, I still felt like I failed—which meant I pushed myself even harder.

I realized that I was undercommitted to what I was trying to accomplish because I overcommitted to performance goals. The remedy was to prioritize my training better so that I was only focused on one performance goal at a time—and then use the other disciplines for cross-training or pleasure. For instance, if I set a goal to run a half marathon, I'd scale back my weightlifting and climbing goals so that I could focus on my running endurance. If I had a climbing competition coming up, I'd scale back on running and lifting to focus on strength endurance and technique for climbing. I fully committed my resources—time, energy, muscle—to one thing at a time and didn't worry about leaving some in reserve for other goals. Focusing on my commitment to just one sport or performance goal at a time had the added benefit of making sure I was never bored with how I trained. I enjoyed it more, and I was more effective.

Sports became the training ground for how I approached all of my responsibilities. I started to see that I couldn't commit to the performance improvements in everything I had said “yes” to. I just didn't have the resources (no one does). Sports are low-stakes, though. I'm not a professional athlete, and I haven't tied my self-worth to whether I can crack running a 5K in less than 23 minutes or not. It was relatively easy for me to dial back my performance targets and focus on one thing at a time. It's not so easy when it comes to work or family. The things we've said “yes” to for work or family have much higher stakes. The shoulds and supposed-tos mix with our fear of not being good enough. We have a sense of identity around responsibilities to work and family, and the validation we seek from them is often central to how we understand our self-worth. So undercommitment continues to be a persistent problem. As we divvy up our resources among #allthethings and become less effective across the board, we feel less useful and less validated. So what do we do? We pursue new responsibilities and projects. We say “yes” again and again, chasing that feeling of validation and worthiness.

And we descend another layer into the spiral.

How Goals Fuel the Spiral

When I started to identify The Validation Spiral in my own life, I wondered what was wrong with me. Was I so broken inside that I had to chase after the approval of others? What undiagnosed psychological condition was causing me to prove my usefulness to society? What maladapted personality trait caused me to continually compromise on my commitments? Since learning that I'm autistic, I've realized that my neurology has likely exacerbated my experience of the cultural imperative of validation through accomplishment. According to a study by Amy Pearson and Kieran Rose in the journal Autism in Adulthood, autistic masking is often a contributing factor to burnout. They find that, to avoid external consequences (e.g., being looked over for a promotion), autistic people may try to “pass as normal” and defy their own innate behaviors. But “passing” (or masking) brings with it greater internal consequences, like burnout.13 I've certainly found this to be true for myself. But autism is not the source of my need for validation.

At first, identifying The Validation Spiral pattern led to a flood of judgment and self-critique. It was deeply unsettling. Researching whether I could change my personality was partially inspired by wanting to rid myself of the spiral and alleviate the constant anxiety that I would never be as smart or accomplished as I desperately wanted to be. And, it seemed that I was the problem. If I could change my personality—become more carefree, more social, more fun—then, surely, I could break out of the cycle. I wouldn't have to rely on the approval or validation of others to feel like I belonged. I'd just belong. Looking back on it now, this seems like a big jump to make. But in the compromise-or-burn-out part of the cycle, fixing the problem-that-was-me was all I had to go on.

The more I investigated my patterns, the more I started to wonder if maybe—just maybe—the problem wasn't with me. Maybe the problem was with how I had learned to operate in the world. The pattern wasn't a defect of my personality; it was a product of self-preservation. The Validation Spiral is how I learned to cope in a world that was begging me to question my worthiness and prove my usefulness. And I also discovered that while being neurodivergent, as well as being a woman, was making the effects of The Validation Spiral more intense, it was something that almost everyone I met dealt with in one way or another. We were all trying to keep up with cultural expectations, stretching to the breaking point to prove ourselves. Once I realized that most people dealt with this pattern to varying degrees, I identified that it wasn't me that was the problem. It was cultural and systemic. In the next chapter, I dig into how underlying cultural forces—like rugged individualism, Protestant work ethic, and supremacy culture—create the conditions that force us to create these coping mechanisms. But for now, I want to explore how goal-setting contributes to The Validation Spiral.

Shirin Eskandani studied to be an opera singer from the time she was young to all the way through college. She moved to New York City to pursue her dream—singing in Carmen at the Metropolitan Opera. While studying opera as a young singer, Eskandani was a big fish in a small pond. But moving to New York City meant that equally talented, equally persistent singers surrounded her. Her confidence was shaken, and she started to question whether she was good enough to achieve her goals. Eskandani persisted. She told me that she believed that, once she got the call to sing in Carmen, she'd know that she was good enough. She'd feel validated in her talent and hard work. When she did finally get the call, a wave of recognition hit her—one that will be familiar to anyone who has tied a sense of worthiness to the achievement of a particular goal. She realized that she still didn't feel good enough despite her accomplishment. There was no revelation of worthiness—just an empty feeling that she would need an even bigger goal to chase.14

It's not just the daily responsibilities and projects to which we say “yes” that keep us trapped in The Validation Spiral. It's also the very goals we organize our lives around. As an elder Millennial, my childhood was organized around getting into a good college. A wave of my Validation Spiral started by saying “yes” to the pursuit of excellent grades and enriching extracurricular activities. AP English? Yes! AP Latin? You bet! Independent-study music theory? Sure! Wind ensemble, Latin club, jazz combo, drum major in the marching band? Yes, yes, yes, and yes. I applied to a well-regarded, small, liberal arts college and won an academic scholarship as well as a music scholarship. It still wasn't enough. Double major? That sounds promising. Chapel worship leader? That might work. Honors thesis? Of course. Just like Eskandani, I kept expecting that the next accomplishment would finally put the need to prove myself to rest. But it never did.

Finally, my top choice graduate school sent me a thick envelope with an acceptance letter and an offer to cover the full cost of tuition. This was it; I was finally on the Ph.D. track. Surely, this would be enough. Instead, a tidal wave of fear and anxiety of whether I was worthy of my position in the program crashed over me. Two weeks before I was going to move into my tiny studio apartment and start school, I withdrew. Call it compromise or call it burnout—it was one of the lowest periods of my life. I was undoubtedly experiencing complete emotional exhaustion as well as feeling distinctly unaccomplished (despite literally accomplishing a huge goal). And that, combined with the worst bout of clinical depression I had experienced to date, meant that I just didn't have the resources to keep going. I took a full-time job in retail management, and the quest for validation started all over again.

Our culture teaches us to organize our lives around goals like these: the perfect role, the dream school, the sought-after title, the wedding, the purchase of a home. The shoulds and supposed-tos become a way to grade ourselves. Meditation teacher Sebene Selassie writes in her brilliant book You Belong, “We learn that appreciation, acceptance, and sometimes even love are connected to how we measure up.”15 Aiming for milestones can undoubtedly be a valuable way to organize our time and action. However, when the goal is a stand-in for validation that you're good enough or a symbol of your identity, the goal can pull you out of your life instead of helping you live it. We often conflate goals with the pursuit of purpose or meaning in life. Then, when we experience the results of working toward that goal (whether we hit it or not), we are left a little lost and confused. Everything isn't different on the other side of that goal. The same questions and concerns about our worthiness remain. We feel unmoored and out of balance until we can find a new goal to organize our lives around—and plunge ourselves back into The Validation Spiral.

Before we can look at how to exit The Validation Spiral and find purpose in practice instead of outcomes and achievement, we need to take an even closer look at the cultural foundations of this problem. While it might fall on us as individuals to deal with and move past the ramifications of The Validation Spiral in our own lives, it's important to understand just how much this is not a problem with us as individuals. It's a social condition that's hoisted on us through pervasive cultural narratives. To break the cycle, we must deconstruct those stories.

Reflection:

- When you were a kid, what did you believe a “successful” life looked like? What influenced your belief?

- Consider a big goal that you set in the past. Why did you set it? How did accomplishing or not accomplishing it make you feel? What story did you tell yourself about accomplishing or not accomplishing your goal?

- In what ways are you overcommitted right now? In what ways are you undercommitted?

- Are you more likely to push yourself to burnout or compromise so you can keep going? Why?

Notes

- 7. Petersen, Anne Helen. Can't Even: How Millennials Became the Burnout Generation. New York: Vintage, 2022.

- 8. Abdulfateh, Rund, et al. “Capitalism: What Makes Us Free? Throughline.” NPR.org, 21 July 2021, www.npr.org/2021/06/28/1011062075/capitalism-what-makes-us-free. Accessed 16 Mar. 2022.

- 9. Hayek, Friedrich A. “Individualism: True and False.” Individualism and Economic Order. (Fifth Impression.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969.

- 10. Orgad, Shani, and Rosalind Gill. Confidence Culture. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022.

- 11. Tulshyan, Ruchika, and Jodi-Ann Burey. “Stop Telling Women They Have Imposter Syndrome.” Harvard Business Review, 11 Feb. 2021, hbr.org/2021/02/stop-telling-women-they-have-imposter-syndrome. Accessed 15 Mar. 2022.

- 12. Nagoski, Emily, and Amelia Nagoski. Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle. New York: Ballantine Books, 2020.

- 13. Pearson, Amy, and Kieran Rose. “A Conceptual Analysis of Autistic Masking: Understanding the Narrative of Stigma and the Illusion of Choice.” Autism in Adulthood, vol. 3, no. 1, 22 Jan. 2021, 10.1089/aut.2020.0043.

- 14. Eskandani, Shirin. “EP 282: Finding Support through Coaching with Wholehearted Coaching Founder Shirin Eskandani.” What Works with Tara McMullin, 26 May 2020, explorewhatworks.com/finding-support-through-coaching-shirin-eskandani/. Accessed 15 Mar. 2022.

- 15. Selassie, Sebene. You Belong: A Call for Connection. New York: HarperOne, 2022.