So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

Genesis 1

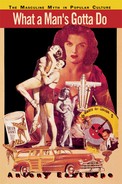

It is time to try to speak about masculinity, about what it is and how it works. This collection of essays looks at the images of masculinity put forward by the media today and analyses the myth of masculinity expressed through them.

Despite all that has been written over the past twenty years on femininity and feminism, masculinity has stayed pretty well concealed. This has always been its ruse in order to hold on to its power.

Masculinity tries to stay invisible by passing itself off as normal and universal. Words such as ‘man’ and ‘mankind’, used to signify the human species, treat masculinity as if it covered everyone. The God of Genesis is supposed to be all-powerful and present everywhere. He first makes ‘man’ in his own masculine image before going on to create male and female. If masculinity can present itself as normal it automatically makes the feminine seem deviant and different.

In trying to define masculinity this book has a political aim. If masculinity can be shown to have its own particular identity and structure then it can’t any longer claim to be universal.

An ancient myth of masculinity, going back to the Greek gods of the sun, equates maleness with light. In Genesis there are certainly men and women but only because he created them. Masculinity has always tried to be present everywhere as the source of everything, and this is what makes it hard to write about. Masculinity has to be unmasked, separated from the role it wants to play by pretending to be the human, the normal, the social.

Two things now make it possible to define masculinity in a critical way, just as they make it politically necessary as well. The first is the revival of the women’s movement since the 1960s. By the very fact of asserting the rights of women and the claims of femininity the women’s movement has put masculinity in question and suggested it has its own particular identity (competitive, aggressive, violent, etc.). In the same period gay politics has openly challenged the idea of masculinity that is promoted on all sides as normal and universal.

Feminist and gay accounts have begun to make masculinity visible. But, written from a position outside and against masculinity, they too often treat masculinity as a source of oppression. Ironically, this is just how masculinity has always wanted to be treated – as the origin for everything, the light we all need to see by, the air we all have to breathe. The task of analysing masculinity and explaining how it works has been overlooked.

Popular Culture

If masculinity is not in fact universal, where is it? The Masculine Myth takes the version which saturates popular culture today, both British and American, in films, advertising, newspaper stories, popular songs, children’s comics. This is the dominant myth of masculinity, the one inherited from the patriarchal tradition. Here it is examined in twenty-two sections. Some are long, some short, but all look at an example of how popular culture portrays men and tries to appeal to them.

Clearly these are masculine fantasies, fantasies of masculinity. When I enjoy a Robert Redford film I imagine I’m Robert Redford but I know I’m not really. Men in fact live the dominant myth of masculinity unevenly, often resisting it. But as a social force popular culture cannot be escaped. And it provides a solid base of evidence from which to discuss masculinity.

Gender can be defined in three ways: as the body; as our social roles of male and female; as the way we internalize and live out these roles. To define masculinity in terms of the physical apparatus, the male genitals, doesn’t get you very far. Sociologists have undertaken important work on the second way of defining masculinity, that is, in terms of male gender roles. But their writing about male behaviour and male attitudes tends to be too descriptive. It relies a great deal on interviews and what men are consciously prepared to admit about themselves. Sociological work does not look at masculinity from the inside, at the way social roles are recreated and lived imaginatively by individuals.

When I was born I did not know whether I was going to be Chinese, English, or Navajo Indian, but still nature had equipped me, like everyone else, with the biological potential to live and reproduce in any of those societies. But biology is not enough. Every society assigns new arrivals particular roles, including gender roles, which they have to learn. The little animal born into a human society becomes a socialized individual in a remarkably short time. Babies born in England go off to school five years later to spend most of the day away from their parents. They can do that because they have internalized and come to live for themselves the roles of the parent society. This process of internalizing is both conscious and unconscious. To understand it fully we need to be able to analyse the unconscious.

Psychoanalysis and Masculinity

This book uses a psychoanalytic definition of masculinity, especially that developed by Freud and later by the French analyst Jacques Lacan. In 1974 Juliet Mitchell published Psychoanalysis and Feminism, an extraordinarily original book which did more than anything else to revive psychoanalysis as a way of understanding gender. It is certainly true, as Mitchell says, that ‘psychoanalysis is not a recommendation for a patriarchal society, but an analysis of one’. Unfortunately it is also true that psychoanalysis is still in part contaminated by the patriarchal assumptions it sets out to analyse. Too often it regards as general something that is only or mainly masculine. Even so, at present there is no clear alternative to psychoanalysis for explaining the internal structures of the self – the fantasies, wishes and drives through which we live out the social roles of male and female. Psychoanalysis may well be inadequate in its account of the feminine, but may still be accurate about masculinity.

A century ago Darwin discovered that the evolution of all species was determined by two needs. A species must be able to make a living by looking after itself and it must be able to reproduce itself. On this basis Freud describes the human psyche as shaped for the most part by two forms of drive. Corresponding to the instinct for self-preservation there is self-love or narcissism. Corresponding to the need to reproduce there is sexual drive. But Darwin’s instincts must not be confused with Freud’s drives. While instinct (Instinkt in German) is simply biological, a matter of genetic inheritance, drive (Trieb) is instinct that has been transformed into symbolic form. The difference is crucial but often misunderstood (and it doesn’t help that the standard English translation of Freud uses ‘instinct’ for both terms).

The distinction means, for example, that when psychoanalysis speaks about ‘the mother’, it is not referring to an actual parent who nurtures you but to the mother as an idea or object that you love. This is the symbolic mother that the infant loves even if its real mother has died and her function has been taken over by an aunt or its father. Even more to the point, for psychoanalysis the penis is not the penis, a fragile and important organ of the body, like the heart or the liver. The penis is a symbolic and cultural object, the phallus. As a cultural object the phallus may attract immense force and charisma while the humble penis carries on as best it can with its usual bodily functions (it is a neatly dual-purpose organ).

There is no shortage of objections to psychoanalysis, and one of the main ones is that it ignores history. Psychoanalysis tends to regard human beings as though they are the same everywhere and always were. This is undoubtedly a valid criticism, and one which psychoanalysis should have come to terms with long ago. For it follows from the distinction between instinct and drive, between the body itself and its symbolic representation, that drive is in part culturally and historically determined.

Patriarchy is almost certainly as old as farming, the advent of which signified the replacement of collective ownership by private property. But this book does not examine the myth of masculinity anything like as far back as that. Nor does it look outside European culture. The myth certainly goes back to the ancient world of Greece and Rome; however, its present form is stamped indelibly by the Renaissance and the rise of capitalism. No attempt to analyse masculinity, even one relying on psychoanalysis, can ignore the way masculinity is defined by history.

One example would be the way gender is given a new definition by capitalism and the bourgeois culture that goes with it. From the Renaissance there has been an increasing economic split between production and consumption, between what is produced for the market and the market it is sold to. Work and leisure, the factory and the home, become widely separated. Accordingly, the idea of male and female becomes similarly separated and polarized. Work becomes masculinized while home and leisure become feminized.

Present-day car advertisements also demonstrate how ideas of gender are always historical. The ads emphasize the sleek, rounded outlines of the latest model, suggesting it has somehow made itself without human labour. And they often link this silhouette to a sharp, shiny image of a woman’s body. In this way commodity fetishism and psychic fetishism are superimposed, and a particular idea of masculinity emerges: he is the master and the car is a she. So a psychoanalytic definition of masculinity cannot be timeless. It must take account of a particular culture and history.

Bisexuality

For psychoanalysis sexual identity has no core, no centre. The infant begins as a wild bundle of drives seeking pleasure without shame wherever it can be found, from the mouth, the anus, the genitals. Not yet he or she, it is ‘polymorphously perverse’ in Freud’s phrase or, in Lacan’s pun, an ‘hommelette’, both a ‘little he-she’ and, like the batter of an omelette in a pan, flowing and spreading without limit or definition. Whatever the external sexual apparatus may say, inside the infant is an active mixture of masculine and feminine, and this potential is never lost. Freud refers confidently and unequivocally to ‘the constitutional bisexuality of each individual’. So everyone acquires a relatively fixed sexual identity but this sexual direction can never be more than a preference, a predominance.

The former Chinese premier Chou En Lai was once asked what he thought of the French Revolution. He replied, ‘It’s too soon to tell.’ The same goes for psychoanalysis. I do not know whether its theories are tenable or not because it is too soon to tell and too little work has yet been done. But it does yield a systematic account of masculinity, one which doesn’t just describe features but analyses them. Psychoanalysis can explain a range of different surface appearances of masculinity in terms of a single, coherent structure underlying them.

As will be seen, a number of main themes recur constantly throughout the twenty-two sections of this book. The examples of popular culture discussed are all treated from the perspective of psychoanalysis. However, the process may also work back the other way. The validity (or otherwise!) of the analysis may confirm psychoanalytic theory. Or it may not. In any case, I shall avoid technical exposition as far as possible, though for each section a list of the relevant work drawn on appears at the back.

If everyone is a mixture of masculine and feminine there is no single such thing as a male, a female, a man, a woman. The Masculine Myth argues that at present masculinity is defined mainly in the way an individual deals with his femininity and his desire for other men. The forms and images of contemporary popular culture lay on a man the burden of having to be one sex all the way through. So his struggle to be masculine is the struggle to cope with his own femininity. From the versions of masculinity examined here it seems that men are really more concerned about other men than about women at all. In the dominant myth it looks as though – as some feminist writing has suggested – women take on more value for men in terms of the game of masculinity than in their own right. It is for this reason that The Masculine Myth is divided into five parts. The first four are about masculinity trying to cope with itself and its other, feminine side. Only the final, longer section looks at men and women together.

This has been borne out by my own experience. Through no choice of my own I was born into a family in which my mother was the only woman. I went to a grammar school, which was all male, and then to university at a men’s college (this has since admitted women). At work my academic department has a teaching staff of twenty-one men and seven women. This experience of living and working in a man’s world is pretty typical. Since men have traditionally had the power to decide these things, it looks as though they have preferred to spend most of their time with other men rather than with women. It also looks as though this separation of home and work has been exacerbated by the development of a capitalist economy.

It is not going to be easy to write about masculinity. One difficulty is that you cannot really define masculinity apart from femininity and a male writer cannot speak for women, of what they are and what they may be. Another is that it is hard for a man to think about masculinity because at present it seems so natural, obvious and close to home. Psychoanalysis helps here since it sets masculinity at a distance and treats it as something to be understood in an objective way. To a large extent I intend to follow the logic of psychoanalysis and see where it leads. But still there is no guarantee that the writing will not warm to the theme of masculinity, endorsing it even while it is being held up for detached inspection. This book may enable others to do better.

So, trying to define masculinity is going to be a tricky and speculative venture. However, for this task psychoanalysis provides one valuable piece of extra assistance. It is an analytic, not a moralizing discourse. This is, I think, a very good thing. To be male in modern society is to benefit from being installed, willy nilly, in a position of power. No liberal moralizing or glib attitudinizing can change that reality. Social change is necessary and a precondition of such change is an attempt to understand masculinity, to make it visible.

The venture has one clear implication. If masculinity is not, as it claims, normal and universal but rather has a particular identity and structure, then it would be wrong to regard masculinity simply as a source, whether of oppression or anything else, as though masculinity were just there, a given. The argument will demonstrate that masculinity is an effect, and a contradictory one. In so far as men live the dominant version of masculinity analysed here, they are themselves trapped in structures that fix and limit masculine identity. They do what they have to do.