CHAPTER 3

Money Habits

THINK RIVER, NOT RESERVOIR

Last summer, my wife, four boys, dog, and I piled into one of those extended SUVs for our annual summer vacation. It takes 12 hours to drive from Atlanta to Ann Arbor where Lynne’s parents live, which is where we always spend the night. From there it’s another four hours to get to Harbor Springs in Northern Michigan.

If you’ve never taken a 16-hour road trip with four kids and a giant 110-pound red Labrador retriever, let me paint you a picture.

I was driving and Lynne was riding shotgun as the copilot, navigator, and backseat referee. Samuel, my youngest, was still in his car seat. My oldest, Ben, was in a regular seat, with Kodie the dog in the middle back, and Luke and Jake in the far back. We had a ton of luggage, four bikes, and a cargo carrier packed to bursting on the roof. Everyone was struggling for seats and space, just trying to survive what even in modern times felt like an eternity in the car.

The reality is that the kids were all on their devices, glued to their screens. But even with all the technology in the world, we ended up having family conversations, intercut with “I want KFC” and “No, I want McDonald’s” and “No, I want Chick-fil-A.”

On this particular road trip, we had a great conversation about turtles.

The boys were watching the latest Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles on their iPad—actually a good movie—when I said, “Guys, did you know that in real life, Galapagos tortoises don’t age? They have the same life expectancy at age 10 as they do at age 50 and 100.”

I only knew this because I had recently interviewed Dr. Andrew Steele for my Retire Sooner podcast. Steele is a biogerontologist and the author of Ageless: The New Science of Getting Older Without Getting Old.

My son Luke, wise to hyperbole at the ripe old age of 11, didn’t buy it. “Whatever, Dad. There’s no way turtles live forever.”

“I’m not saying they live forever,” I countered. “They do die—they can get caught in a boat propeller or die from an infected cut, and they’re still susceptible to disease. But genetically, they don’t age. Their life expectancy doesn’t change.”

I told them about the oldest Galapagos tortoise on record, Adwaita, who died in a Calcutta zoo in 2006. Adwaita was said to be 250 years old, first taken to India by British sailors during the reign of King George II.1

I was winning the boys over, I could tell.

“So how old is the oldest turtle today?” asked Jake.

“One hundred ninety years old. That means it’s been alive since before the Civil War.”

Even Luke looked impressed.

I wasn’t going to subject my kids to the latest episode of my podcast—but I did share more of what Dr. Steele told me. He believes that aging is “the single most important scientific challenge of our time.”2 In his book, he talks about how Galapagos tortoises get old without getting elderly. In the scientific community they describe this as “negligible senescence” when an organism does not exhibit evidence of biological aging. The larger implication, of course, is that we two-legged humans might be able to master “biological immortality” and become ageless too.

It may sound like pie in the sky, but Dr. Steele isn’t a quack: he’s a respected biologist. And he’s not alone. Scientists around the world are figuring out how to take the knowledge gleaned from tortoises and other unaging animal species to create a medical solution—not a fountain of youth, but a way to increase our life expectancy. Steele told me they’re treating aging as a disease that could be helped, cured, or slowed down. Maybe we’ll be able to live one year longer. Maybe five. Maybe 20. We don’t know. But it’s in the works.

Here’s my question for you. If you live 1, 5, or 20 years longer: how are you going to make your money last?

Let’s say that, over the next few years, the biogeneticists get their way. Dr. Steele and his fellow scientists harness the age-defying potential of the Galapagos tortoises, and suddenly, if you take the right supplements—and assuming you steer clear of boat propellers—you can tack on an extra 10 years to your projected life span. Congratulations! That’s 10 more years of being the Happiest Retiree on the Block.

The trick, of course, is figuring out the money side of the equation. If you’re reading this book at 40 and live to be 115, will your money last as long as you do? And I don’t mean just surviving: I want you to thrive. Even 65 is a super young retiree if you’re going to live 50 more years. I want to make sure you have enough to live your best, fullest, longest, most purposeful life.

Will you live to be over 100? I certainly hope so. I’m not qualified to read your future—I deal in investment portfolios, not crystal balls. What I am qualified to tell you is that there are certain principles to follow before and during retirement to ensure your money lasts.

In the chapters that follow, we’ll be delving into the engaging, empowering, enlightening habits of the happiest retirees. But first we have to lay the financial foundation for our HROB house—and it all starts with good money habits. In this chapter, I’m going to share with you the transformative money rules and strategies that unite the Happiest Retirees on the Block.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: there are three core, actionable money habits that nearly all HROBs have in common. If you can check these off your retirement to-do list, you will be on your way to Happy Town, population: you.

The happiest retirees have:

1. At least $500,000 in liquid retirement savings. That’s the inflection point for happiness: half a million. A net worth beyond $500,000 doesn’t have nearly as much impact on higher happiness levels as getting to $500,000. Meaning, even as your savings continue to climb, your happiness won’t necessarily rise at the same rate it did from zero to $500,000. Liquid retirement saving simply means that this is money you can access with ease, such as stocks, bonds, mutual funds, ETFs, cash, etc.

2. A mortgage payoff that is complete or within sight. This is a big one. We’ll touch on it here, but a discussion of mortgages and other home-related habits takes center stage in Chapter 10.

3. Multiple streams of retirement income. It’s right there in the chapter subtitle: think river, not reservoir. Actually, think many rivers. These tributaries will carry you away to retirement happiness.

In this chapter, we’re going to dig a little deeper. We’ll investigate the principles that go into each of these three money habits, including:

• Taxes, Savings, Life (TSL) Budgeting

• The One-Third Mortgage Payoff Rule

• The Rich Ratio

• Fill the Gap (FTG)

• The Retirement Grey Zone

Let’s take a look at how to apply each of these rules and strategies—and why they matter for you.

$500,000 IN LIQUID RETIREMENT SAVINGS

Once a certain amount of wealth is attained, people experience diminishing marginal returns of happiness. As you already know, I’ve termed this phenomenon the Plateau Effect, and it’s a key factor in determining how much money we need to be happy during retirement.

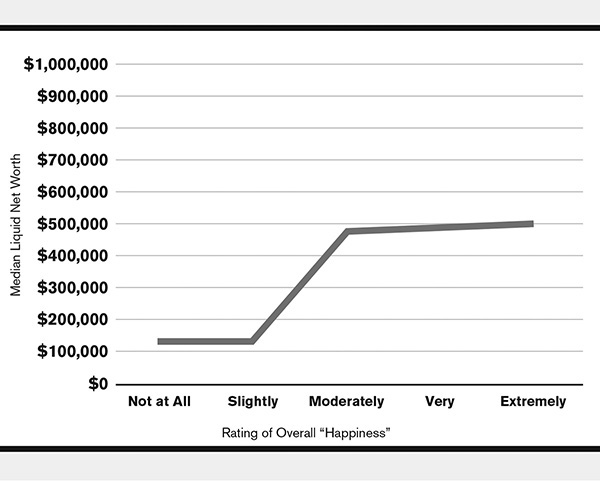

My research on happy retirees has yielded real and specific numbers to back up the Plateau Effect. In terms of liquid net worth (including stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and cash), retirees with around $100,000 reported feeling unhappy or just slightly happy.

Here’s where it gets really interesting.

See how the line levels off at the top of the graph in Figure 3.1? Looking at median data on liquid net worth, the $100,000 mark was where folks were stuck in the not happy or only slightly happy zone. But once they hit $500,000, they moved decidedly into the moderately happy through extremely happy zone.

FIGURE 3.1 Happiness by Median Liquid Net Worth

How did I reach this number? It’s the product of both my professional experience and extensive research. The results of my survey made it crystal clear: with just a half-a-million-dollar nest egg, you can live a happy and financially secure retirement. While everyone’s exact economic needs vary, this number can work for retirees who carry little debt and don’t live an extravagant lifestyle. Instead of setting your sights sky-high for numbers like $2 million or $10 million, you should first aim for a healthy $500,000 in savings.

Of course, $500,000 may still sound like a lot of money, especially if you’re a twenty- or thirtysomething who’s still accumulating wealth. I’m not saying half a million is chump change. But it is a much more attainable goal than $2 million, and no matter your income level, you have a better chance of reaching it.

How? You start by budgeting.

I’ve always recommended a straightforward budgeting methodology where for three months you’re very intentional about tracking your spending. If you are able to track it via a software program, fantastic. You can also manually add up your expenses at the end of every month using your credit card or bank statements.

The easiest budget program ever created is what I call my TSL (Taxes, Savings, Life) budgeting approach. In preretirement, approximately 30 percent of your income should be allocated for taxes, 20 percent for savings, and 50 percent for life (all the necessities and fun!).

Let’s say you have 40 years to invest and build for your retirement. If you simply take $100 each month and invest it, assuming a 10 percent return and that your investment compounds monthly, you’ll have a sweet $637,000 at the end of those four decades.

A 10 percent annual rate of return, you say? You may be surprised by the following. Despite three wicked bear market corrections over the past 20 years, the S&P has still averaged over 7 percent per year, including reinvested dividends.3 During this time, REITs, a common option in most 401(k) plans, have averaged over 10 percent per year.4 And over even longer periods of time, such as the past 40 years, the S&P 500 has averaged over 11 percent per year when dividends are included. I’m not saying these returns have been a given for most investors, nor is there a guarantee that this profitable run will continue forever. However, if you have a long time horizon, 20 years or more, then using a 10 percent assumption in this example is constructive.

So there you have it. The secret to a happy retirement isn’t having $2 million in the bank, no matter what Suze Orman may tell you. On a recent podcast, Orman raised eyebrows with a bold statement about how much money people need to retire. “You need at least $5 million,” she said, “or $6 million. Really, you might need $10 million.”5

Really, Suze? A number like that cuts most people off at the knees before they even get started. Suze may want you to work forever, but I certainly don’t.

Happiness in retirement is about having a simple plan, getting started, and being committed to having at least $500,000 saved up by the time you retire. The vast majority of the HROBs featured in this book do not have millions upon millions in retirement savings—and they were still able to stop working and live joyful, fulfilling lives.

A MORTGAGE PAYOFF THAT IS COMPLETE OR WITHIN SIGHT

I believe the happiest retirees enter post-career life either mortgage-free or within five years of hosting a mortgage-burning party. This insight comes from the extensive research I conducted for You Can Retire Sooner Than You Think.

The argument you’ll hear from the camp of pro-mortgage pros is that you can do better by investing your savings as you continue to pay interest on your house. As an example, these planners say that, instead of using $100,000 to pay off a 4 percent mortgage, you should invest it in the market, where you could see a return of, say, 8 or 10 percent. The result: a net 4 to 6 percent gain.

Hmm. This logic looks good on paper, but it may not hold up as well in the real world. As we all know, the market can drop or stay flat for relatively extended periods of time, and our gains should be measured in decades, not years. And since the average life span of a mortgage in the United States due to frequent housing moves is less than 10 years, this timeline might not work.

I’m a believer in the One-Third Rule. If you can pay off your mortgage with no more than one-third of your nonretirement savings accounts, you should consider doing so. For our purposes, nonretirement simply means after tax brokerage or savings accounts, not your 401(k), IRA, or retirement savings plans from work. If you owe $50,000 and have $160,000 in savings, drop that bomb on the mortgage. You will still have $110,000 in liquid assets to ease you along the retirement road.

In addition to financial considerations, think about how your mortgage affects your emotional health. I’ve learned from the happiest retirees that there is a real sense of peace and serenity that comes with knowing you own your house free and clear. It just feels good as you enter a new phase of life that is chock-full of changes.

Eliminating a house payment also dramatically lowers your monthly retirement living expenses, taking the pressure off your nest egg and other sources of monthly income. This step leaves you with more money to follow your dreams and passions—for travel, hobbies, or charitable giving. In other words: your core pursuits. That’s what a happy retirement is all about.

But you must be sure that you can afford this peace of mind without putting undue strain on your financial fitness. It is rarely a good idea to use retirement-account money—IRA, 401(k)—to pay off a mortgage. Remember, paying off your mortgage is about creating peace of mind. Tapping your retirement nest egg too heavily too early might end up being counterproductive. Large withdrawals from an IRA or 401(k) to pay off a mortgage can dramatically raise your tax bracket and cost you more in taxes than if you were to spread out your mortgage payoff over time.

So if you can’t dump a pile of money on your mortgage right now, consider paying a little extra each month. This way, you can shave months (or years) off the time that you’ll be making payments. And you will be further on the road most traveled by the HROBs: living mortgage free.

MULTIPLE STREAMS OF RETIREMENT INCOME

For all you devoted readers of my first book: Do you remember Rich?

Rich Ratio, that is. We talked about the Rich Ratio in You Can Retire Sooner Than You Think, but here’s a refresher: this is my system of making sure you are living below your means because that’s the crux of wealth building. Put simply, the Rich Ratio is a straightforward way to measure the amount of money you have in relation to the amount of money you need.

Here’s how to determine your Rich Ratio:

First, calculate your total monthly income. If you’re still working and looking for the ratio you’ll likely have during retirement, then use projected values. Remember to consider all possible retirement income streams: paychecks from part-time work, Social Security and/or pension benefits, rental income, miscellaneous sources, and, of course, the amount your investments should produce. Also, make sure to adjust this number for taxes so you have a “net income” number to work with.

Now that you have an income figure, it’s time to calculate your needs. To do this, simply use your projected monthly retirement budget. With these two numbers, our equation looks like this:

Have ÷ Need = Rich Ratio

For the more visual folks out there, why we want a ratio of 1 or more may be clearer now. The reason is that we want what we have to be greater than what we need. In economics, supply and demand ratios fluctuate, but when it comes to being a happy retiree, what we have (supply) must always be greater than what we need (demand).

This system works regardless of your income level. A Rich Ratio greater than 1 is fantastic. A Rich Ratio under 1 means there is room for improvement. Let’s say you generate $8,000 per month (after taxes) and you only need $4,000 to meet your obligations, giving you a Rich Ratio of 2. You’re rich! If your monthly income is $1 million, but your spending needs are $2 million (Rich Ratio 0.5), then I’m sorry to report that you are poor.

HROBs have to figure out how to bring money in the door once they head into retirement. While it’s nice to get a steady paycheck from an employer or to pay ourselves (as business owners), we have to change our mindset before we retire. When it comes to generating income, it’s a good idea to go from relying on one income stream to many.

Essentially, you’re creating as many tributaries as possible to come together in one new, predictable, larger river of income. You likely already have ideas about where you can gain other sources of income. These could include multiple pensions, Social Security, rental properties, investments, or part-time work.

Let’s talk for a moment about part-time work. There are many retirees who may be ready to retire from a full-time career but are still interested in working at least part-time. In fact, an estimated one in five retirees continues to work in some capacity after leaving their full-time careers. If you’re interested in working part-time to have an income stream in retirement, consider a job doing something you’re passionate about. Maybe it’s something completely unrelated to what you used to do. Or if you loved what you used to do, you might try consulting. While part-time work may be less income, be less secure, and include fewer benefits, it’s a great way to bring in a supplemental paycheck once your main career comes to an end.

Maybe you were earning $250,000 a year and almost killing yourself in the process. Now you might decide you don’t really need to save any more money, so you can stop putting money into that bucket. This could potentially mean downshifting from a $250,000 annual salary to a $50,000 salary, rather than stopping work entirely. You’ll obviously earn less at this part-time job, sure, but on the plus side: your overall tax rate should fall dramatically.

Maybe you were a teacher or scientist, and now you can work from home a couple of days per week. Maybe you were a nurse like my wife, and you can choose to practice via telework instead. Maybe you’re in the real estate industry—residential or commercial—and you can work from home now and only keep a handful of clients. Being an attorney is great for this sort of thing. Billable hours, baby!

There are so many ways to use your original skills in a much less demanding environment while still making enough money to avoid tapping much, or any, of your savings. Whatever your profession, find a way to make a smart, meaningful downshift. There are multiple methods to identify the gap in your income and take the right steps to fill it.

Which brings me to my next strategy.

FILL THE GAP

One of the biggest worries about retirement is that you won’t have enough money set aside when the time comes. Knowledge is a powerful weapon for battling fear. The more we know about any challenge, the less scary it becomes.

Allow me to introduce my Fill the Gap (FTG) strategy, a simple but powerful way to understand how much money you need in retirement and how much your investments have to contribute to meet that need.

FTG consists of three simple steps:

1. Figure out your post-retirement net income. This part should be simple. Take all of your guaranteed income streams (from sources like Social Security and pensions) and add them up. Then deduct what you will likely owe in taxes. If you know you’ll be getting $3,500 per month (after taxes), then this number is your “take-home income.”

2. Determine your monthly spending. Tally up all of your monthly expenses. You may use Excel, Quicken, or just good old-fashioned pencil and paper. For this example, let’s say your monthly expenses come out to $5,000 per month.

3. Find your gap. Subtract your take-home income from your spending needs. Here, we have: $5,000 – $3,500 = $1,500. That $1,500 figure is the perpetual gap you must fill. Remember that it will need to be adjusted over time for inflation and as your spending changes.

That gap will ideally be filled by your nest egg. According to the well-established 1,000-Bucks-a-Month Rule—really more of a rule of thumb—someone who retires at the typical age of 62 to 65 needs $240,000 in savings for every $1,000 a month they need to fill the gap.6 (This assumes a 5 percent annual withdrawal rate.) So in the scenario above, the retiree would need $360,000 in savings to meet their monthly needs. ($1,500 × 12 months = $18,000/year divided by 5% = $360,000)

There are nearly endless ways to approach investing for retirement. Growth, momentum, long-short, international, small cap, venture, private equity—the list goes on. I happen to be partial to a style called income investing, as is can help you get comfortable with how much your portfolio is generating in cash flow (not just growth) in any given year. On the income side, income investors can aim for at least 3 or 4 percent yield on client investments.

What exactly are we talking about here? Cash flow. Income. We are homing in on the dividends, interest, and distributions that investors can enjoy from income-oriented stocks, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), bonds, real estate investment trusts (REITs), and master limited partnerships (MLPs). Investors can often get to a 3, 4, or even 5 percent annual yield, which is the actual cash flow portion that is paid out to you or added to your account. Note that your cash flow should only be part of your overall total return equation

On the appreciation side, the situation is more fluid, as returns tend to fluctuate with the stock market and the overall economy’s performance. As a rule of thumb, you should shoot for an annual gain (over time) of another 4 to 5 percent from this part of the equation.

Combine our two factors and, depending on your risk tolerance, you should be looking to achieve an overall annual percentage of somewhere in the 5.5 to 10.0 percent range. All things considered, I’ve found this to be a reasonable range, provided you have a long and patient time horizon, and the risk tolerance for asset fluctuation.

I want to restate the importance of using after-tax dollars in your FTG calculations. Retirees often see a dramatic drop in their overall effective tax rate once they stop working, so it pays to do some research into your projected tax rate.

For example, let’s say you were used to seeing 30 to 35 percent of your paycheck go to various taxes. Once you retire, it’s not uncommon to see that tax rate get cut in half. Typically, your overall effective tax rate goes down because your income goes down: you’re controlling your income by only withdrawing what you need, and while Social Security benefits are trickling in, the amount of that check is likely going to be less than your paychecks were. So as a general rule, a person’s (or a couple’s) Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) decreases once they retire.

“But, Wes,” you say, “my financial situation is unique. FTG won’t work for me.” I beg to differ. Everyone’s situation is unique. But while your specific circumstances may be a little different than our cut-and-dry example, you can still use FTG.

I’ve seen people use this strategy despite variations in life: marital status, age differences between spouses, pension versus no pension, fear of stocks, fear of bonds, kids versus no kids, employee versus business owner. The list goes on. But part of the beauty of FTG is that it can be applied to anyone’s retirement strategy, no matter the specific financial or life situation.

While we all have our own unique combination of variables, using the FTG strategy will help you work toward achieving your financial goals. Instead of dreading your retirement years and worrying you’ll run out of money, you can rest easy at night knowing what your gap is and how you plan to fill it. If that’s not a recipe for a happy, fear-free retirement, I don’t know what is.

A quick note on the 1,000-Bucks-a-Month Rule: this is a very general rule of thumb to help you understand what you need to accumulate when you’re young. It uses a nice round number to give you a guide for how much to save. Later on, when we talk about budgeting, we’ll get a lot more specific. In Chapter 12 we’ll do a deep dive on the 4 Percent Plus Rule, and why it matters.

DON’T LET RETIREMENT SCARE YOU

We’ve all heard the doom-and-gloom stories about retirement: you need millions socked away for your money to last (thanks, Suze); you’d better push your retirement age back to 70 to make sure you have enough money; if you do X without doing Y, you’ll be living on public assistance before you know it.

No wonder folks these days question whether they will ever be able to retire.

The horror stories get published because they’re attention grabbers—and they work because they play on our fear and insecurity about stepping into this new chapter of life. They paint reality in black and white, without allowing any room for grey.

The truth is, adjusting to retirement—especially early retirement—is not an instant process. Like anything good in life: it takes time. But that’s actually not a bad thing. It simply means you are entering what I call the Retirement Grey Zone.

WHAT IS THE RETIREMENT GREY ZONE?

A lot of folks think it’s either one way or the other, black or white: you’re either still working, or you’re retired.

That might not be so, particularly for anyone eyeing an early retirement. Cue the theme song from The Twilight Zone. You may be entering the Retirement Grey Zone.7

Don’t worry—it’s not as dramatic as it sounds. Depending on your age when you retire, you may not begin receiving Social Security immediately. Medicare enrollment may be a ways off. That pension you’re so lucky to have? That may not start paying out right away either. And what about the part-time gig you’ve been eyeing for months?

All of these factors will play a key role in what the Retirement Grey Zone looks like for you. While each retiree’s financial plan is different, there are some key fundamentals that influence income streams—those tributaries we talked about earlier—when we consider retirement-focused federal programs, pensions, and part-time jobs.

Because retirement and investment planning exist along a multiyear timeline, a day-one approach to planning often doesn’t capture the entire picture. If all of our benefits and income streams kicked in the day after we retired, then, sure, planning would be a breeze.

Over the past several years, I have developed something I call the retirement timeline. This is a simple planning tool that can help anyone map out retirement, particularly those who end up in a Grey Zone.8

Here’s the method I use with the families I help. I start by drawing a timeline: literally a straight line across the page, starting with the year you begin your planning. Then from left to right, I fill in important financial years along the way. Let’s say I’m working with a husband and wife who are both currently around age 60. In our chronology, when they get to age 62 and are first eligible to receive Social Security, we may choose to add in those monthly checks.9 At age 65, we account for the rich Medicare benefit. If either one (or both) has a pension, we mark when this benefit starts to pay out income.

Other issues make the chronology that much more important. Do you have a date set for when you want to start working part-time?10 We can pencil that in. What about if your spouse has a different income and benefits timeline because of an age difference? We can chart that, too.

As we fill in each income stream, I also include what the couple’s investment income (from their retirement savings) will be in the year they’ve set for retirement.11 For ease of understanding and readability, each income stream is color-coded with a legend. With just a quick glance at the timeline, retirees can get a sense of where they are on their unique financial retirement timeline, and where they’re going.

The result is a useful tool: a clear and concise one-page financial plan that maps all of the expected income resources that will kick in sometime after retirement.12 A powerful road map for the future.

Really, just a one-page plan? Yes! I much prefer my one-page version of financial planning to an overly complicated 50-page plan. While those phone-book-size plans can be great for some retirees, they run the risk of being overly complicated and fluctuate massively with small changes to assumed rates of return and inflation assumptions. Plus, in my experience, the more complicated the plan, the more unlikely it is for families to stick to it.

In reality, most of us will live in the Retirement Grey Zone for a while. To map our way through this zone, my simple and cohesive one-page, color-coded timeline features key financial milestone dates and plots how income sources layer together. Our goal is to project the income you’ll have available each month during retirement. Then you can quickly chart your budget (and fun) according to this easy-to-understand chronology.

The bottom line: fear not. The Grey Zone is a journey—“a journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination,” as Rod Serling would say. Planning for it doesn’t have to be scary. This is a time when we are easing into full retirement. We may not be traveling 24/7, but we’re not working 60-hour weeks either. This translates into less pressure from work and more time to enjoy our newfound freedom.

HSAS AND THE RISING COST OF HEALTHCARE

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you know the cost of healthcare in America continues to rise. While this affects all of us, it’s particularly impactful for retirees and pre-retirees.

In the 1980s and 1990s, many Americans took healthcare costs for granted. As long as you had a healthcare plan at work, the deductibles were relatively manageable because companies carried most of the weight.

Today, nearly the opposite is true, as a significant portion of large companies are switching to high-deductible healthcare plans as the rate of inflation in healthcare has skyrocketed. According to a recent Fidelity study, the average couple will need an estimated $295,000 for medical expenses over the life of their retirement—and that doesn’t include long-term care.13

Perhaps the most practical way to plan for this is to understand the magnitude of these costs. Medicare doesn’t kick in until age 65, so if you are planning to retire before that, you need a stopgap solution to cover you until you turn 65. You can get that coverage by purchasing any sort of private plan, whether through a large health insurance provider or the healthcare.gov exchange.

I strongly urge you to consider increasing contributions to your tax-advantaged accounts, especially an HSA (health savings account), if you have one. HSA contributions, earnings, and distributions used to pay for qualified medical expenses are tax-free for federal income tax purposes. If you have an HSA account available at work, contribute to it. I think of HSAs as 401(k) accounts specifically for healthcare costs.

We all know that healthcare costs are a huge part of the retirement equation. My advice is to learn more about HSAs and how they work, and then see what’s available. If you’re 55 or older, you can make an additional $1,000 contribution annually to your HSA.

You can take steps today to help prevent exorbitant healthcare costs from chipping away at your retirement happiness. There are solutions—you just have to know where to look.

MONEY IS A VEHICLE

Imagine, if you will, a neighborhood of happy and unhappy retirees just going about their lives. The UROB is in his lavish backyard, snacking on candy bars, admiring his BMW 7 Series while sitting beside a swampy, mosquito-infested lake. Yes, it’s a metaphor. The lake represents the “reservoir” of money that—surprise, surprise—doesn’t make him happy. Has he ever swum in that lake?

Absolutely not. He hasn’t exercised since 1993.

On the other side of the street, the HROB is sitting in her modest backyard, admiring the brightly colored pansies she planted herself (gardening: a high-ranking core pursuit for HROBs). She’s just gotten back from a brisk tennis match with her best friend (exercise and socializing: two more HROB list toppers), and is now having a gin martini with her daughter, while her grandson plays in the backyard fort (time with children/grandchildren: another HROB fave). At her feet, multiple bubbly streams of water flow like tributaries into the large river behind her house.

Yes, it’s another metaphor. She understands money is a river, not a reservoir. If she gets the flow and timing just right, she can enjoy the retirement of her dreams—even if she lives to be 250 years old like an esteemed Galapagos tortoise.

At the end of the day, the purpose of having money is not just to have money. Money is a vehicle to get you where you want to go. Once you’ve got your Rich Ratio right and know how to Fill the Gap, you’re well on your way. That means you can turn your attention to the fun part of being the Happiest Retiree on the Block: doing what you love with the people you love.

Now that the money rivers runneth, let’s grab a kayak and paddle like hell to those core pursuits.