Chapter 9

Analyzing Customer Requirements

The proposal development phase begins once you receive a draft or final RFP. During this phase, you integrate your bid strategy with customer requirements and transform the product into a winning proposal.

A clear understanding of customer requirements is a prerequisite to winning. Customer requirements come in two flavors: informal and formal. Informal requirements are the needs, desires, and fears of your customer bounded by the specific need being solved. They are determined through marketing efforts and pre-proposal contact with the customer. Formal requirements are those defined by the RFP. They take precedence over informal requirements. Nonetheless, both should be combined and used to develop your proposal.

Oftentimes, formal RFP requirements can be interpreted only in light of informal customer knowledge. Be careful, however, about how you use knowledge about informal customer requirements. Adding requirements to those contained in the RFP, or significantly expanding the scope of RFP requirements, will increase your cost, which could undermine your chances of winning.

Formal customer requirements are determined through an exhaustive analysis of the RFP. What might appear to be a straightforward process frequently becomes an arduous and confusing undertaking. Even under the best circumstances, analyzing the customer’s RFP to define program and proposal requirements poses a challenge. Many government RFPs are disjointed, inconsistent, inaccurate, or fraught with ambiguities. Some RFPs are so disorganized that they require considerable translation and interpretation before they make sense. (In fairness to government procurement agencies, assembling an RFP that effectively and consistently communicates the government’s requirements is a major challenge. Moreover, sometimes RFPs are clear, concise, and reasonably well-organized.)

Preparing a coherent proposal response amidst inconsistent, contradictory, and confusing RFP requirements is just a part of the job. Those who learn to decipher RFP requirements and meet customer requirements gain competitive advantage. Those who do not suffer the consequences.

Having a good understanding of customer requirements before the RFP is released is a big advantage. You can use this knowledge to fill in the gaps and interpret vague and inconsistent RFP requirements. In other cases, poor-quality RFPs may offer opportunities for creative interpretation that can be integrated into a bid strategy.

Chapter 7 describes how to review a draft RFP and respond to inconsistent or missing RFP information. This process can be used for both draft and final RFP documents. In either case, the capture team must decide how to handle such problems.

GETTING STARTED

Assemble the proposal team and make RFP reading assignments. Make sure all team members understand their assigned RFP analysis tasks. For small procurements, have the whole team read the entire RFP. Otherwise, the core capture team should read the entire RFP. Other members of the technical proposal team can limit their reading to Sections B, C, L, and M, plus any technical attachments such as a statement of work, statement of objectives, product specification, etc. Your contracts manager should thoroughly review Sections B through K and any contracts-related portions of Section L.

Do not permit proposal team members to read only the section of the RFP pertaining to their technical specialty. Everyone on the proposal team should be familiar with the overall technical requirement. This will make it easier to coordinate different technical disciplines and to integrate individual proposal sections.

Plan to make three passes through the RFP to accomplish your initial RFP analysis. During the first reading, skim the information without taking notes or stopping to analyze requirements. This will provide you with a general sense of overall RFP requirements. On the second reading, take notes and highlight significant RFP sections, especially those that require additional analysis. Finally, read the RFP the third time to confirm or adjust your initial findings. Everyone should make a list of questions, concerns, ambiguities, or inconsistencies resulting from the RFP review. The capture team can then review those lists to determine the action required. You will need to resolve any apparent RFP inconsistencies to ensure that everyone understands the customer requirements your proposal is supposed to address.

RFP ambiguities can be handled in several ways. First, you can ask the customer a question to clarify the problem. If you choose to ask a question, use the guidelines presented in Chapter 7. Remember, bidders’ questions and the government’s responses normally are provided to all bidders. Second, you may use your knowledge of the customer to resolve an inconsistency or ambiguity. Finally, you can decide to leave an ambiguous RFP requirement unaddressed and interpret the requirement in your favor. If you interpret a RFP ambiguity in your favor, then list this interpretation as an assumption in the contract section or basis-of-estimate portion of your cost proposal. Note: Your interpretation of an RFP requirement can not contradict actual RFP requirements. That is, you cannot make the RFP state what you want. Instead, if one reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous requirement can be made, and that interpretation is in your favor, you can accept that interpretation.

Never interpret an ambiguity in a way that is detrimental to your approach. By definition, an ambiguity can be interpreted realistically in several ways. Given a choice, always interpret ambiguities to your advantage.

Using RFP Ambiguity as a Competitive Advantage

To illustrate how you can use ambiguity to your advantage, consider the following example. Our proposal team was bidding a contract that included development and production phases. Development costs were bid on a cost-plus basis, but production was bid as a firm fixed price. (Chapter 14 explains different contract types.) Part of the contract required us to design and install a series of complex computer networks and interconnect networks at a variety of locations. Unfortunately, many of the building drawings were not available. Therefore, we were faced with the prospect of bidding expensive T-1 lines without knowing the layout of individual buildings or what it would take to install the networks.

The RFP was unclear about whether installation was a development or a production task. Different proposal team members argued ardently for each interpretation. Bidding installation as a production task with a firm fixed price represented enormous cost risk. To offset this risk, we would be forced to increase our bid price significantly, which could have made us less competitive. Alternatively, if we bid installation as a development task, we could limit our risk by defining the task. If the actual task turned out to be more extensive, we would be able to increase our cost under the cost-plus terms of the development contract.

Our choice in this case was either to ask a question or to interpret the RFP ambiguity in a way that would allow us to mitigate a significant cost risk. By asking a question, we risked getting an answer we could not stand. In addition, by asking the question, we would alert the competition and thereby lose the opportunity to use this area to our advantage.

Eventually, we decided to treat the network installation as a development task. We included installation as a development task in our work breakdown structure (WBS) dictionary, listed it in our assumptions, and made it a part of our cost basis of estimate. We won the contract, but not without worrying about whether the government would view our approach as unresponsive to RFP requirements.

Reading the RFP

There are many approaches to reading and reviewing RFPs. Here is an approach I like.

Start with RFP Section B. It defines what the government is buying and what you must deliver. It typically is where you enter your proposed price, or it references a pricing form or matrix to be used for your pricing. Next, read Section C. It provides a description of the technical requirements of the contract. If the RFP includes a more detailed statement of work or product specification, it will be provided as an Attachment to Section J of the RFP. Briefly read these documents. Do not stop to take notes or highlight points. Just get an overview of the requirements.

Then read Section L, sometimes titled “Instructions to Offerors (ITO)” or “Proposal Instructions to Offerors (PIO).” Note the basic proposal format instructions, the number and types of proposal volumes, and specific instructions on how to prepare each volume or section, along with the specific technical questions to be addressed. Then read Section M, which lists and describes the evaluation criteria that will be used to select the winner. Sections L and M together tell you what must be included in the proposal and how your response will be scored.

Next, skim Sections D and E. They identify specifications for marking, packaging, shipping, and inspection. Then review Section F. It lets you know when items must be delivered to the government—the foundation for your program schedule. Section F may also contain exercise dates for contract options and the period of performance for individual contract line item numbers (CLINs). Finish the RFP by briefly reading any additional RFP attachments, and conclude by skimming Sections G through K. Pay a little more attention to Section H, which contains special contract clauses. Sometimes special requirements contained in this section have a significant technical impact.

Most of the information in Sections G, I, and K will be of interest only to the contracts manager assigned to the proposal. Once you have a general feel for what is required, begin the RFP analysis in earnest. Before submitting your final proposal, expect to read the RFP about a dozen times. Each reading will likely produce a fresh insight into RFP requirements.

KEY PROPOSAL PREPARATION DOCUMENTS

Formal customer requirements provide the foundation for your program approach and the ingredients of your proposal. Three documents should be prepared to support proposal planning and preparation: (1) program requirements document, (2) proposal requirements document, and (3) evaluation criteria document. Chapter 10 describes a further refinement of customer requirements to develop a detailed proposal road map.

Program Requirements Document

Prepared by the program manager, the program requirements document summarizes the technical requirements of the contract. As part of your bid strategy development, you should already have identified program requirements. If so, this document should be nearly complete by now and need only to be updated based on RFP specifics.

Read RFP Sections B and F and summarize the contract deliverables. If the contract includes separate lots or options, make sure to note them. Develop a high-level program milestone schedule based on this information. If possible, create the schedule with a commercially available software package like Microsoft Project. If the contract includes options, you must include start and delivery dates for each. Sometimes, RFPs provide only a not-later-than date for option exercise. If this is the case, use those dates as the start dates for initial schedule development. Remember to keep it simple; this is just a summary of requirements.

Attach a copy of the program WBS to the program requirements document. Some RFPs include a WBS. If so, you might need to expand it to accommodate your costing efforts. If not, develop one. The WBS provides the foundation for collecting cost estimates. (Pricing for most service contracts does not follow a WBS format.)

Review RFP Sections D and E. Note any special test or inspection requirements, and incorporate test dates into the program schedule. Also, list any special test locations or provisions and any special packing or handling requirements. Finally, list any key, special, or critical performance requirements from the statement of work, specification, Section H, or any of the RFP attachments. Special requirements include things like quality assurance requirements (e.g., ISO certification), software certification level, minimum requirements for key personnel, equipment reliability or availability penalties, associate contractor agreements, or anything required to perform the contract.

If the RFP includes a list of contract data requirements list (CDRL) items, summarize CDRL deliveries on the program schedule or attach a list to the requirements document. If you are required to build your own CDRLs, you may need to add these to the program requirements document after you have developed your program planning.

The program requirements document provides a concise (two pages or less) summary of the contract requirements and milestone schedule, plus any peculiar or specific requirements. Everyone on the proposal team should review the requirements document and have a copy handy for reference.

Figure 9-1 shows a sample program requirements document for the JTW program.

Proposal Requirements Document

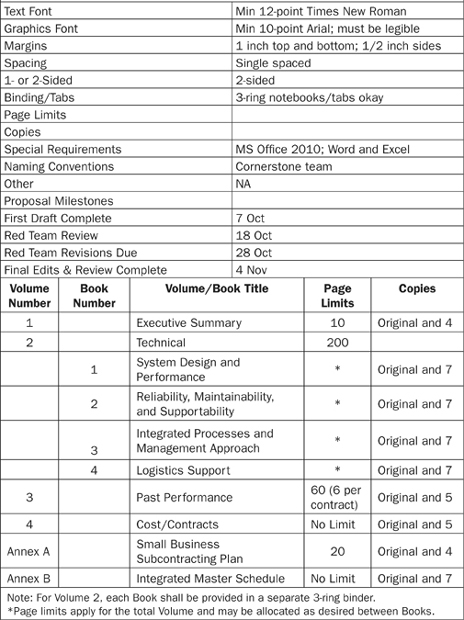

Prepared by the proposal manager, the proposal requirements document summarizes the proposal preparation requirements. Information for the document is obtained from Section L. Section L lists the required proposal volumes, the number of copies required by the government, page limitations, how the proposal should be bound (e.g., three-ring binder), and whether an electronic copy of your proposal is required. It also includes basic instructions for proposal organization and format (e.g., required type and font, line spacing, page margins). If the RFP does not specify format, use whatever standard format your organization normally uses for technical documents or ask the customer if it has a preference.

Figure 9-1. Program Requirements Document for the JTW Program

Include any additional plans or documents required as part of the proposal submittal. Some RFPs require bidders to prepare their own statement of work and CDRLs. Others require preliminary plans, such as a configuration management plan or a transition plan. Many development-type contracts require an integrated master plan and integrated master schedule as proposal submittals. The proposal requirements document should include all plans and attachments required by the RFP, organized under the volume in which they will be submitted.

The proposal requirements document should contain proposal milestone dates for key events, such as when the first draft is due, proposal review dates, final editing and quality assurance, and delivery to the customer. A more detailed proposal preparation schedule will be developed and distributed to the proposal team; milestone dates are key events everyone should keep in mind to coordinate organization-level efforts.

Include basic proposal conventions, standards, or any style requirements in the proposal requirements document. This will help minimize confusion among proposal authors. It will also minimize subsequent efforts to correct or standardize this type of information. An example is how you will refer to your company in the proposal. If you are the American Standard Telecommunications Company, will you refer to yourself with the entire name, use an acronym (ASTC), or use a shortened name (American Telecom)? Issues like this might seem trivial, but experience suggests they can consume an enormous amount of time and effort to resolve. This is time better spent on more important matters.

As a rule of thumb, do not use acronyms or abbreviations for company names unless you are IBM or AT&T, which are recognizable to everyone. Instead, use a shortened version of the company name. Evaluators are more likely to remember this name than an unfamiliar acronym.

Include in the proposal requirements document things like how you will refer to your proposed program “team” if it includes major subcontractors, the use of personal pronouns like “we” in place of your company name or program team, whether you will capitalize the title of program personnel such as “Program Manager,” how you will handle acronyms, how you will refer to your customer, and whether you will express units of measure as metric, U.S., or both. Every proposal will be different. When it doubt, put it in the documents. Doing so will save you much wasted time later when time is an especially precious commodity. Once you build a proposal requirements document, you can use it on subsequent proposals by tailoring it to meet the specific requirements of each proposal. Figure 9-2 shows a sample proposal requirements document.

Evaluation Criteria Document

If you want to win, you must write to the evaluation criteria used to score your proposal. A careful analysis of the evaluation criteria is a prerequisite to preparing a winning proposal. Section M contains the evaluation criteria that will be used to evaluate your proposal. Everyone on the proposal team needs to be familiar with these criteria. Individual authors must be intimately familiar with the criteria that correspond to their assigned portion of the proposal.

Figure 9-2. Proposal Requirements Document for the JTW Program

Prepared by the proposal manager, the evaluation criteria document summarizes the relative weight of evaluation factor and subfactor criteria.

Subfactor weights can be used to determine preliminary page count limits for proposal sections. This is especially valuable for page-limited proposals. You want to put your emphasis where it will do the most good. The relative importance of evaluation factors and subfactors can also provide guidelines on how to allocate your proposal resources. Again, the greatest emphasis is placed on those factors that are more heavily weighted.

However, a caution is warranted here. There are no unimportant proposal sections. In your zeal to maximize your score for heavily weighted factors, do not neglect factors that are relatively less important. This is a common mistake with significant consequences. All factors and subfactors are important and contribute to the final proposal score. One poor score can drag down the entire score for a factor or subfactor.

Dissecting Evaluation Criteria

The first step is to identify the evaluation areas or factors that will be used to evaluate your proposal. Every proposal is evaluated in at least two areas: technical and cost. In addition, contract information will be checked to ensure that you comply with RFP requirements. Some agencies evaluate past performance and assign it a point score. Other agencies, like DoD, assign past performance a risk rating and combine it with the technical evaluation. All of this information is typically contained in RFP Section M.

Here is a Section M example in which the evaluation factors are not equally weighted:

Proposals will be evaluated using the four factors, which are listed below. Technical is equal in importance to Past Performance, and each is more important than the Cost/Price factor, which is significantly more important than the Small Business and Small Disadvantaged Business Subcontracting Plan factor.

A. Technical

B. Past Performance

C. Cost/Price

D. Small Business and Small Disadvantaged Business Subcontracting Plan

The relative importance of these evaluation factors can be expressed as follows:

Technical = Past Performance > Cost > Small Business Plan

Even though you do not know the exact relative importance of these factors, you can estimate them fairly accurately. Start by assigning each factor the same weight. Then adjust the weighting of each factor based on the information contained in Section M. If each factor in the above example is weighted equally, it would account for 25 percent of the total evaluation.

A general rule for adjusting factor weights is: Adjust each factor by 5 percent when it is greater/lesser in importance and 10 percent when it is significantly more or less important than another factor. Applying this rule produces the following relative weights for the example above:

Technical (30%) = Past Performance (30%) > Cost (25%) > Small Business Plan (15%)

You can vary relative weights forever. But you will quickly discover that there is not a lot of variability in how you assign weights if you want to remain consistent with the language of Section M. It depends on how you judge terms like more important and significantly more important. You can make finer adjustments based on your experience and knowledge of the customer. You can also use the relative emphasis given to corresponding topics in Section L to make additional adjustments.

Some agencies use a point-scoring system in which areas and factors are assigned a set number of points. For these cases, no further analysis is required to determine the relative weight of areas and factors.

Most RFPs further divide factors into subfactors and identify their relative importance. From the example above:

The following Technical subfactors are in descending order of importance:

T.1 System Design and Performance

T.2 Reliability, Maintainability, and Supportability

T.3 Integrated Processes and Management Approach

T.4 Logistics Support

If the subfactors were of equal importance, they would each be worth 25 percent of the total score for the technical area. Arranging the four factors in descending order of importance with a 5 percent gap between them produces the following weighting:

T.1 = 32.5%

T.2 = 27.5%

T.3 = 22.5%

T.4 = 17.5%

The resulting evaluation factor document is shown in Figure 9-3. It is unlikely that subfactor weights are calculated to the decimal point, as shown above. However, for our purposes such minor considerations are inconsequential.

Figure 9-3. Sample Evaluation Factor Document

If one factor or subfactor is significantly more important than another, Section M typically will say so. The difference in relative weights may be less than 5 percent, but if it is very small, the government is more likely to say the factors are of equal importance. Alternatively, the relative difference may be greater than 5 percent. Again, if the relative difference is much greater, Section M would likely use terminology to make this point.

The important point here is that you can derive a reasonable estimate of the relative weights given to factors and subfactors using the information contained in Section M. Remember, however, that this is an estimate. It should be used only as a guideline or a point of reference for making preliminary decisions about things like page count allocation. At the same time, it does provide the proposal team with a view of the relative importance of the areas and factors that must be addressed in the proposal.

Sometimes the evaluation factor for cost is divided into subfactors. If so, Section M will identify the subfactors and define their relative importance. In those cases, use the technique illustrated above to estimate the relative weight of each cost factor.

DOCUMENT CONFIGURATION MANAGEMENT

Following a review of the program requirements document, proposal requirements document, and evaluation factor document, and any necessary revisions, they are placed under configuration control. That is, no one is permitted to change them without permission from both the program manager and the proposal manager. If one of these documents is changed, a new copy is provided to each proposal team member, along with a summary of the change. In addition, ask each member to confirm that he or she has received and reviewed the change.

Translating RFP requirements into a set of proposal management documents might not appear to offer much in the way of gaining competitive advantage. Admittedly, this part of the process is not rocket science. Nonetheless, a thorough and effective RFP analysis, and the preparation of a set of documents to guide proposal development, might produce a higher return on investment than you imagine.

Create the proposal development documents described here to set the boundaries within which you will prepare your proposal. Use this information to structure your proposal, set the foundation of your technical approach, and understand how the government will evaluate your response. Make these documents readily available to the proposal team, and ensure they are kept up-to-date so everyone is reading from the same page. This alone will enhance team effectiveness and efficiency.

The first step of a long journey is often the most important. Head in the wrong direction at the outset and you may never arrive at your intended destination. Use this phase of the proposal development process to take that initial first step toward preparing a winning proposal. Gain advantage over those who slight this phase and rush unprepared down the path to defeat.