C

Reviewing a Project Plan

This appendix describes the final TSP launch meeting and your role in that meeting. It covers the subjects to review and the questions to ask. It also includes a brief Plan Assessment Checklist to guide you in this review.

The Executive Role in Team Building

When engineers complete the TSP launch process, they present their plan in a final management meeting. You or some other executive or senior manager must attend this meeting. When no senior manager shows up for the final meeting, the engineers feel that they have wasted their time and their work is not important. One key reason for holding the launch is to motivate the team and get them excited about the job. Your participation will help do this.

During the final launch meeting, ask questions. This will help you to understand the engineers’ plan and will demonstrate your interest in the work. The principal mistake that many senior executives make is to not ask enough questions. Not only does this imply that you are not interested in the team’s plan, but it also misses an opportunity to ensure that the engineers have a plan they can meet and that this plan will produce the product you want on a date you can accept.

The team has spent several days producing a detailed plan to do the job that you asked them to do, and the team leader has just presented it to you in the final management meeting. Suppose the plan includes a later date than you had asked for. What should you do? The answer is discussed in more detail in the following paragraphs, but the short answer is to probe the plan to identify any mistakes or omissions. You may find that the engineers have allowed more time for some activities than is reasonable, but this has never been my experience. I almost always find that the engineers have overlooked things that, when included, will actually lengthen the schedule.

After you have satisfied yourself that the engineers have produced a credible plan, you still may not be happy with their date. However, now you know that this is the best available estimate for the job. If the team produced a schedule that was longer than you requested, they also should have produced several alternative plans to show what they could do with more resources or how the product could be delivered in versions. You can explore these alternatives with the team to see which make the most business sense. You can also try to think of other options that would better fit your needs.

If the engineers’ plan or one of their alternatives is acceptable, the team will have a sound basis for doing the job. If not, they may be able to estimate some other alternatives on the spot, or they may have to come back in a day or so with a revised plan. At the end of the meeting or possibly a day or so later, you will have a plan on which you and the engineers agree. You will also have a motivated and committed team. Another important result is that the team will have a detailed process and plan for doing the work.

The Final Management Meeting

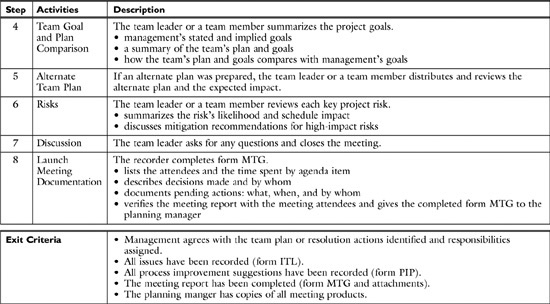

In presenting the team’s plan, the team leader will follow the LAU9 script shown in Table C.1. This is an example of the scripts that TSP teams follow in producing their plans and in doing their work. The TSP process uses scripts to guide engineers in consistently doing a job. A script is like the checklist that pilots use before a flight. It does not tell them anything they did not already know, but by following it they are less likely to forget things or to make mistakes.

In following the LAU9 script, the team leader first asks two team members to fill the time-keeper and recorder roles. These roles are specified by the TSP to help teams hold efficient meetings and to record and track important decisions. Once these roles are selected, the team leader will review the meeting agenda and objectives, describe the work done during the launch, and compare the team’s plan with your goals. He or she will also discuss any alternate plans and review the risks that the team sees in meeting the plan.

After the team leader’s review of this work, there is time for discussion and questions at step 7 of the LAU9 script. You could ask questions at any time during the meeting, but the team has done a great deal of work and will present a lot of information; by waiting until the discussion period, your questions will be better informed and less likely to cover topics that the team will later address.

The Launch Products

In presenting the team’s plan, the team leader will show the results of the team’s planning work and distribute copies of many of the launch work products. The typical products of a team launch are shown in Figure C.1.

Table C.1 TSP Launch Meeting 9—Script LAU9

Figure C.1 TSP Launch Products

These products describe the team’s plan in considerable detail. In addition to helping the team agree on what to do and how to do it, these launch products also provide the detailed guidance needed to do the job. Since these products are produced principally to help the team do the job, you need not review or attempt to understand them. They are distributed both to demonstrate that the team has done a complete job and to provide backup material for answering your questions. The launch products are briefly described in Table C.2.

The Plan Presentation

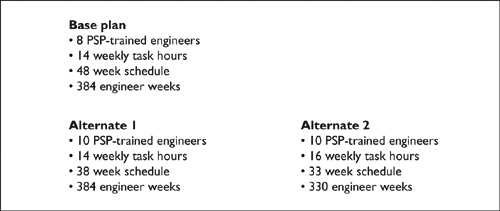

After reviewing the meeting agenda and describing the work that the team has done during the launch, the team leader will show a summary of the team’s plan. In one example of such a presentation, Janet, the team leader, first described the team’s strategy. She then showed the plan data in Figure C.2 and explained that the engineers made a detailed estimate of the planned product, defined the tasks to build this product, and estimated the time required for each task. (She could review the entire plan if you wished, but she plans to present only a summary of the plan data.) She explained that the plan schedule was 15 weeks longer than management had requested, but that the estimated total budget of 384 engineer weeks was slightly less than the planned project budget of 400 engineer weeks.

Since the plan did not meet management’s goals, the team had examined several alternate plans, as shown in Figure C.3. The first alternate plan would require immediately adding two more PSP-trained engineers to the project. Since there were several such engineers whose projects had not yet started, Janet suggested that two of them be assigned to this project, and that additional engineers be trained in the next scheduled PSP class. She also pointed out that adding these engineers would cut the schedule by ten weeks, which still would not meet management’s goal. However, adding engineers would not increase the budgeted cost, because the total required engineer weeks would be the same in both cases.

Figure C.2 Project Plan

Janet then explained that alternate 2 would meet manage-ment’s 33-week goal and reduce budgeted costs by 12%. Since this alternate required that the team achieve an average of 16 weekly task hours instead of the 14 in the plan, she planned first to discuss the task-hour problem as the team saw it. She explained that the engineers had planned only that part of their work that they could estimate and track, which included only the time to design, build, and test the product. These task hours did not include such other activities as coordinating with the hardware engineers, planning, team status meetings, meetings with management, and the many other things they had to do.

Figure C.3 Alternate Plans

The engineers had talked to members of other TSP teams and found that 14 weekly task hours was an achievable goal but that 16 hours was much more difficult. However, they were willing to commit to the 16 task-hour objective if management agreed to the actions required. They expected to need some clerical support, an adjustment in working hours, and permission to work occasionally at home. They also wanted to block certain times of the week when they could work without interruption and when no meetings involving them would be called. They would develop more detailed recommendations in the next couple of weeks.

Janet next discussed the project risks, using the charts in Figures C.4 and C.5. Then she asked for questions and comments.

Figure C.4 Major Risks—1

Figure C.5 Major Risks—2

The Plan Assessment Checklist

In probing the team’s plan, your objective is to arrive at a realistic plan that the team will commit to and that meets business needs. A suggested set of questions to do this is given in the Plan Assessment Checklist in Table C.3. As shown in the checklist, your first questions should focus on the team’s plan and alternate plans. If the team’s plan is acceptable, then probe it to ensure that it is realistic and will produce a quality product. The Plan Assessment Checklist walks you through a set of questions to accomplish this objective.

The Business Assessment

The first step in the assessment is to compare the team’s plan with business needs. There are three general situations:

1. The team meets or exceeds the goal.

2. The team cannot meet the goal as planned, but could do so with more resources.

3. The team cannot meet the goal under any conditions.

Table C.3 The TSP Plan Assessment Checklist

The Team Meets or Exceeds the Goal

If the team’s plan meets the goal and you feel the plan is reasonably accurate and realistic, proceed to the rest of the plan assessment. In the example, the team produced a 48-week schedule as opposed to the desired 33 weeks. In this case, the engineers produced two alternate plans, one of which met management needs and was accepted.

The Team Needs Added Resources

As in the case of Janet’s project, the most common situation is that the team could meet management’s desired schedule, but only with added resources. Assuming the engineers presented an alternative plan that showed what they could do with more people, they have done their job and you must make a decision. You can either add the needed resources, proceed on the longer schedule, or explore other alternatives.

If the team has not presented an alternate plan to meet your goals, ask why not. Is there some reason that additional resources would not help, or did the engineers not think to make an alternate plan? Teams generally can accelerate schedules by adding resources, but the added resources must be properly trained and available in time. If the alternate plan is satisfactory and you and the project managers agree that the needed resources can be obtained, move on to the rest of the plan assessment.

The Team Cannot Meet the Goal

Occasionally, teams will not see how to meet the business need. Presumably, they will have produced the best plan that they could devise and have presented it to you for approval. At this point, you should carefully examine the team’s plan to see if there are any variations that might meet the business need. If so, have the team produce a suitable alternative plan.

If you cannot think of an alternative approach that would likely meet the business needs, examine the engineers’ plan to make sure it is realistic and properly made. If problems exist that, if corrected, will likely make the plan acceptable, have the team take the time to correct the plan and review it with management again. If no acceptable alternatives appear likely, thank the engineers for their work, conclude the review, and hold a separate management meeting to reassess the business needs and decide what to do.

The Plan Assessment

After you have concluded that the team’s plan or an alternate plan will meet your needs, review that plan carefully to ensure that it was made professionally and that it adequately represents the work to be done. The remainder of the plan assessment process follows the general strategy shown in Figure C.6.

As shown in Figure C.6, the planning process starts with the conceptual design, which in turn determines the size estimate. Based on the size estimate and historical productivity data, the team can estimate the task hours for the development work. Similarly, the size estimate, together with the team’s quality plan, determines how many defects must be removed in testing and how many task hours will be required for that testing. With the development and testing task hours, together with the team’s weekly task-hour plan, the team can produce the schedule. This suggests that the conceptual design be the first item to examine, followed by the size estimate, the productivity estimate, and the quality plan.

The Conceptual Design

In making a TSP plan, teams first estimate the sizes of the products they will build and then use productivity data to determine how long the work will take. Before they can estimate the sizes of the products, however, they must have some idea of what the products will look like. Then they must determine the product structure and define its principal components. Because teams do not have time to produce a full product design during the launch, they must produce a conceptual design. This conceptual design represents the team’s current thinking about how to design and build the product. The engineers then use this conceptual design as the basis for making the size estimate.

Figure C.6 Plan Assessment Elements

You need not assess the conceptual design itself, but you should ask the engineers how comfortable they are with the design. If it is similar to other designs that the engineers have worked on, it will be reasonably good. If only a few of the engineers have worked on similar products, however, the conceptual design is likely to contain errors and omissions. Then there is a reasonable chance that the job will be significantly larger and take longer than planned. When engineers have not worked with similar systems, they often omit key functions or assume that important functions are simpler than they turn out to be.

The Size Estimate

After discussing the conceptual design, ask about the size estimate. Did the engineers compare this size estimate with similar prior products? Even if only two or three of the engineers have worked on similar products, if they used historical data to make the estimate and they feel confident about the estimate, the estimates for each of the system parts are probably pretty accurate.

The Productivity Estimate

Ask how the team’s planned productivity compares with the engineers’ experience, both in the PSP course and with other projects. In the TSP, overall productivity is measured in LOC per hour for the total job. What did the engineers use for productivity numbers, and where did they get those numbers? Engineering productivity for complete TSP projects usually is between one and ten LOC per task hour.

One important factor to consider in assessing team productivity is that new development work typically has higher productivity than modification or enhancement. Also, the development productivity for more complex communications or systems control programs generally falls at the low end of the productivity range, while application development work usually has higher productivity.

The Task-Hour Measure

Since variations in the weekly task-hour rate can have a major impact on project cost and schedule, thoroughly explore the basis for the weekly task-hour estimate. As Janet explained in the example, in a normal 40-hour work week, engineers do many things other than designing, coding, and testing. These other tasks can take a great deal of time, and every minute spent on these activities is a minute that the engineers cannot spend on developing the product.

If this is a first-time TSP team, these task hours should probably average about 10 hours in the first few weeks and then gradually build up to about 14 to 16 task hours per week. Further increases generally require a long-term improvement program. Until teams have historical data, it is risky to plan for more than this. When teams pick larger numbers, they frequently fall behind schedule and have trouble recovering. In reviewing the task-hour plan, ask about the data that the engineers used to make the plan. Do they have prior data on their own work, on the organization, or on similar teams in other organizations? If so, how do their planned task hours compare with these other teams, and what assumptions did they make in picking the task-hour rate for this project?

Once the organization has task-hour data, management should consider ways to help the team improve its weekly task hours. Remember, however, that the task-hour rate is a motivational issue. Management edicts to improve weekly task hours usually are counterproductive. Focus on what management can do to help the engineers improve their own task time. The engineers know that their weekly task hours are important, so trust them to set their own goals and help them to achieve these goals.

An Example Plan Comparison

Janet’s project illustrates the kinds of comparative plan data that team leaders should show. In answer to management’s questions, she showed the chart in Figure C.7 and explained that the organization had historical data on only three projects. Although these were not TSP data, several of the team members had worked on these projects and felt that the numbers reasonably represented what happened. She had also talked to finance and obtained the working hours and engineer week data.

Based on these comparisons, it appears that the team’s project plan is very aggressive. From the LOC/week numbers, productivity is about 50% higher than two of the projects and nearly three times that of the third. Since the team’s project was a large and relatively stand-alone addition to an existing application, Janet believed that the higher productivity was realistic. She also pointed out that project B consisted of many small coding changes in a large system; this is the least productive kind of software work.

Since these plan numbers look very aggressive, management should be concerned about an overcommitment and an exposed schedule. Without better historical data, however, there is no good way to tell. One approach is to accept this plan for now and to watch carefully in case the estimate is too low. If it turns out to be too low, management might have to add more PSP-trained engineers to the project or accept a later delivery.

Figure C.7 Plan Comparisons

Evaluating the Quality Plan

There are three reasons to ask about the quality plan. First, your interest in quality will send the right message. Emphasize that the quality of the engineers’ work is more important than the schedule. Second, the quality of the work will have a direct impact on the schedule. If some engineers do poor-quality design or implementation work, the entire team will waste time in finding and fixing the resulting defects. Third, quality is important to the business. For poor-quality products, field repair and warranty costs often exceed development costs. Every defect that a customer finds costs time and money and damages your reputation. While you need not examine the quality plan itself, you should ask questions about it.

Continuing with the previous example, in answer to the questions on quality, Janet showed the chart in Figure C.8. She pointed out that this was the organization’s first TSP project, so none of the other projects had comparable quality data. Therefore, she compared the team’s plan with the TSP quality guidelines, which provide quality goals for teams to use when they do not have other project data.

Janet next explained that the team planned to find 68.7 total defects/KLOC. This might seem like a large number, but actually it was below the quality guideline range of 75 to 150. Even with this low total defect density, however, the total number of defects to be found and fixed during development was 1,700. By using thorough reviews and inspections, the team planned to remove 97.3% of these defects before the first unit tests. This would result in 5.6 defects to be found in system test, and another 8.4 (2.5 + 5.9 = 8.4) defects left in the product at delivery. Finally, Janet explained that yield before system test was very important. If, like most projects, the team achieved a yield before system test of only 80% to 90%, the engineers would have to spend another 2,000 to 3,000 hours in testing.

Figure C.8 The Quality Plan

Assessing the Plan

After reviewing these items, you should be able to judge the quality of the team’s cost, schedule, and quality plans. If the plans were thorough and the engineers’ answers were clear and logical, compliment them and move on to the risk assessment. However, if the engineers have not used available data, consulted resident experts, or built on prior work, thank them for what they have done but ask them to take more time to finish the job.

The plan provides the foundation for everything the team will do. If inaccurate or incomplete, it will not provide useful guidance. Using a poor plan is like driving a car with a broken gas gauge: you might not run out of gas right away, but the longer you drive, the greater your risk. By having the engineers fix the plan, you establish the principle that you will not accept incomplete or incorrect work. Standards start at the top, so to consistently get quality work, start by insisting on a properly made and complete plan.

Examining the Team’S Risk Assessment

Once you have assessed the team’s cost, schedule, and quality plans, ask about the risk assessment. The team has evaluated the risks that the engineers think are most significant and presented a few of them to you. You will not want to review all these risks, but check that the major risks have been considered and that the team has identified where it needs help.

Meeting Conclusion

After your questions have been answered, thank the team leader and team members for their work and congratulate them on what they have accomplished. Also say a few words about the challenges ahead, and explain that you are counting on the engineers to do a superior job. Finally, conclude with a clear and concise statement of your decision on the team’s plan and a quick review of any required follow-up actions. The team leader will then close the meeting by having the meeting recorder read the outstanding action items, the person assigned to handle each item, and the follow-up date.

Summary

The following eight principal points are made in this appendix:

1. When the engineers have completed the TSP launch, they will present their plan in a final management meeting.

2. An executive or senior manager must attend this meeting.

3. The purpose of the plan review is to convince you that the team has made a thorough and realistic plan for doing the job.

4. Follow the Plan Assessment Checklist to review the team’s plan.

5. In doing this review, ask about the conceptual design, size estimate, productivity estimate, quality plan, and risk assessment.

6. By doing a thorough review, you satisfy yourself that the plan was made competently and you require the engineers to defend it.

7. Once the engineers have defended their plan and you have accepted it, they will be highly motivated to meet their commitment to you.

8. Close the review with a brief summary of your decision about the plan and a review of the outstanding action items.