CHAPTER 9

The Social Networks

I HAVE A LOT in common with Richard Rosenblatt. We are about the same age, are both entrepreneurs, and have both run public and private companies. We also share the kind of eternal optimism that irks many people. But what sets Rosenblatt apart from me is that he was chairman and CEO of MySpace, one of the most widely publicized companies in the world of social networking.

Rosenblatt cut his teeth with DrKoop.com and iMALL, the second of which was sold very profitably to Excite.1 After that he managed eUniverse, a company that once had looked forward to a bright future until it was mismanaged and delisted from the NASDAQ exchange. That was when Rosenblatt jumped in.2

Rosenblatt doesn’t look for problems within companies; he looks for opportunities. So when he took over at eUniverse, he changed the name to Intermix, got it back on the NASDAQ, and looked for assets in the company that he could exploit. One of those was a little-known site called MySpace.

MySpace was created by two employees at Intermix after they saw the huge success of Friendster and my company Classmates. com.3 Under Rosenblatt’s leadership, MySpace grew to more than two million members within a few months.4 But for all its success, MySpace was still third in size behind Classmates.com and Friendster.

Long Live MySpace

How did MySpace beat Classmates.com and Friendster and come to dominate the world of social networking? Because Classmates. com was my company, let me start there and tell you how it happened from my perspective.

Classmates.com was founded by Randy Conrads in 1995 to serve, you guessed it, former high school classmates trying to reunite. The site was free to use and had great success in driving traffic. But like many Internet companies, it had very little advertising revenue to support the business. Then the founders changed the business model and started charging for access to the network. These changes made Classmates.com profitable by 2001, but they stunted its growth—and made it vulnerable to free social networks.

By the time my company took over Classmates.com in 2001, it had 1.4 million paying subscribers and nearly 38 million registered users. It was here that our team made a big mistake: we became enamored of (better wording might be “paralyzed by”) our profits and forgot the principle of the first stage of networks, Metcalfe’s big bang—namely, that one should grow a network unencumbered. By focusing on profits instead of the growth of the network, we encumbered ourselves and let Friendster and MySpace eclipse us in size.5

As for Friendster, MySpace beat that site for a different reason. Founded in 2002 by Jonathan Abrams, Friendster was the dominant social network by 2003. Although Classmates.com was largely considered the first social network, many people credited Friendster with the launch of Web 2.0 and hailed Abrams as an Internet wunderkind. Time flagged Friendster as one of the best inventions of 2003, and Entertainment Weekly hailed Abrams as “the friendliest man of the year.”6

In fact, Friendster was enjoying a meteoric rise in both media attention and growth. The company tapped no less than Tim Koogle, former CEO of Yahoo!, to take the reins as CEO. As with most growing networks, the growth was akin to a brain’s neural development in the early stages—fast and furious. Here was a company poised for success.

But the growth was so large and so fast that it nearly brought the company’s technology to a halt. Load times, for instance, typically exceeded a minute per page.7 But that is not what killed Friendster, nor, as many people assume, was the great success of MySpace the reason for its demise.

In addition to technical problems Friendster was hit by a phenomenon called fakesters. These were fake profiles set up by charlatans. One hacker pretended to be Bill Gates; another, Bill Clinton. Others included Jesus, Elvis, and R2D2. Although these fakesters were phonies, their sites were wildly popular.8 But Abrams, the young and somewhat abrasive founder, wanted the fakesters “ . . . all gone. All of them.”9

But removing the fakesters cut off thousands of connections within the network, leaving abandoned many other legitimate profiles that were linked to them. If Abrams had been more familiar with neuroscience, he might have realized that Friendster was killing its most popular neurons. But he didn’t—and that’s when Richard Rosenblatt jumped in.

Recognizing that Friendster was going down the wrong path, Rosenblatt had MySpace embrace the fakesters.10 As far as he was concerned, users could befriend their neighbors, Barack Obama, or even Ronald McDonald. Within months of this decision, MySpace’s users surpassed Friendster’s, and within a year, MySpace had twenty-two million users to Friendster’s one million.11 These days, MySpace has more than one hundred million users (meager only if compared to the U.S. population of three hundred million).12 MySpace sees more traffic than Google and signs up more users every day than the populations of Green Bay and Kansas City combined.13

Will MySpace Implode?

By following the laws of networking, MySpace became a phenomenon and eventually was sold to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp in July 2005 for nearly $600 million.14 Less than a year later, Google cut an ad deal with MySpace worth a reported $900 million.15 In 2006, Murdoch said that MySpace was worth more than $6 billion. 16 And MySpace continues to grow, following the curve of Metcalfe’s law.

Now, however, you can see signs that MySpace is exceeding the inflection point of networks. Not including the highly publicized child pornography problem, security issues are growing graver, highlighted in 2008 when more than a half million user pictures were uploaded to another site.17 Because anyone can build and create a page on MySpace, consistency is lacking and searching is growing more difficult. And even though MySpace continues to grow, by early 2008 MySpace had begun to see a slowdown in the rate of its user growth.18

But the core problem, ironically, is that MySpace continues to grow at all. MySpace is likely past the inflection point for a network. This is causing all sorts of user problems that should result in constriction, but the MySpace team is fighting it. My sense is that it should stop growing now—before it implodes. To be sure, MySpace is in a heated battle with a new competitor, and on the Internet, for better or worse, the perception is that size matters.

So MySpace is pushing to increase usage, traffic, and registered users. But this practice is causing problems that will frustrate users and ultimately destroy the network. The biggest problem is that the network is becoming untenable and unnatural. When you join a social network such as MySpace, you expect to connect with people you know, reconnect with those you have known, and reach out to those you want to know. The community grows and thrives based on those three assumptions. But when a network grows too large, your ability to connect to others becomes overwhelming. If you search for John Smith on MySpace, you will receive five hundred pages of names (roughly five thousand people), but only because MySpace caps the number of pages per search at five hundred. Hopefully you are not John the 5001st, and heaven forbid if you are trying to find someone named John Smith.19

Users are constantly bombarded with requests to befriend people they do not know. Occasionally, this is not a bad thing. Who isn’t touched by having someone reach out to be friends? But imagine getting such solicitations numerous times per month, per week, per day, and even per hour. The value of a network does not increase with size when the size of the network makes it impossible to derive value from it.

Even worse, because of the numbers of people trolling on MySpace (and the lack of restrictions), it is easy for someone to find you randomly. Predators, in particular, are on the site looking for money, credit, computer fraud, or sex. The nation saw the horrifying effects of this when Dateline NBC aired a recurring segment on child pornography called “To Catch a Predator,” which showed child molesters using MySpace and other sites to meet unsuspecting children. The danger has become so serious on MySpace that forty-nine U.S. attorneys general banded together in 2008 to issue guidelines for social networking.20

I suspect that what is happening on MySpace is the following (I say “suspect” because independent sources of user data are notoriously unreliable). The number of registered users continues to grow, but the number of active users is likely stalling. This is because curiosity continues to prompt new users to try the network, but many find it too overwhelming to be useful. These new users, along with large groups of existing users who have seen a decrease in value because of the new users, will likely become inactive.

As a former MySpace user, I can attest to a decreasing value because of the size of the network. Certainly, heavy users and those who have established strong relationships on MySpace will continue to be very active, but they will not necessarily gain value from the increased size of the network—a sure sign that Metcalfe’s law is no longer relevant.

MySpace execs are likely struggling with a network that has reached its equilibrium point. They should be weeding out the low-impact, inactive, and irrelevant users, just as the brain weeds out the least-viable neurons through a process aptly called cellular suicide. Now is the time for pruning.

MySpace should also be limiting users’ ability to connect with others in an effort to match the growth of the network to the value curve. This approach is different from artificially cutting the network because of an ideological concern (such as what happened to Friendster); this is genetic fitness, à la cellular suicide. But instead, the company’s leaders are adding fuel to the fire.

Facebook’s Network of Networks

On top of everything else, the team at MySpace should be particularly concerned about Facebook, the (relatively) new kid on the block. In fact, I suspect that by the time this book is published, Facebook will be the largest social network on the Internet, surpassing MySpace in users and page views.21

Like Microsoft, Facebook was started by a Harvard dropout. Founder Mark Zuckerberg wanted to connect with all of his Harvard classmates, and so he launched Facebook in February 2004.22 It was a hybrid of Classmates.com and MySpace, except that Facebook was only for Harvard students. That very limitation made it a huge success: while MySpace was growing out of control, Facebook gave its Harvard users the control and community rarely seen in the larger social networks. Before the end of its first day, Facebook had registered twelve hundred Harvard students. By the end of its first month, more than half of Harvard’s student body was online .23

That’s when Zuckerberg took a risk. He quit Harvard, moved to Silicon Valley, and raised venture capital from Founder’s Fund, the same group that started eBay’s PayPal and Napster.24 Starting with Harvard, Facebook methodically enlarged its network to additional Ivy League schools, then to all colleges and universities, and then to all schools. Finally, Facebook opened to the world in September 2006.

By then, Yahoo reportedly had offered the twenty-two-year-old Zuckerberg nearly $1 billion for the company.25 Most people thought Zuckerberg was nuts, but he turned Yahoo! down. Then Microsoft stepped up just as Facebook reached 30 million users and attained a growth rate that eclipsed every site on the Web except MySpace.26 Microsoft bought less than 2 percent of the two-year-old company in 2007 for a reported $240 million (and for anyone having trouble with the math, that would value Facebook at roughly $15 billion).27 Zuckerberg was not nuts (Microsoft, I am less sure of).

What I find interesting about Facebook is its resemblance to Jim Anderson’s network of networks. Zuckerberg, like most entrepreneurs, stumbled on a model of the mind through trial and error instead of understanding the brain. Recall that Anderson realized that the brain is not as homogenous as researchers had once thought. On top of that, the number of neural connections is not very great. The average neuron has roughly 10,000 connections to other neurons in the brain. But the total potential connections is about 1010 (100,000,000,000). In other words, actual connectivity is only about 0.0001 percent of what it could be.28

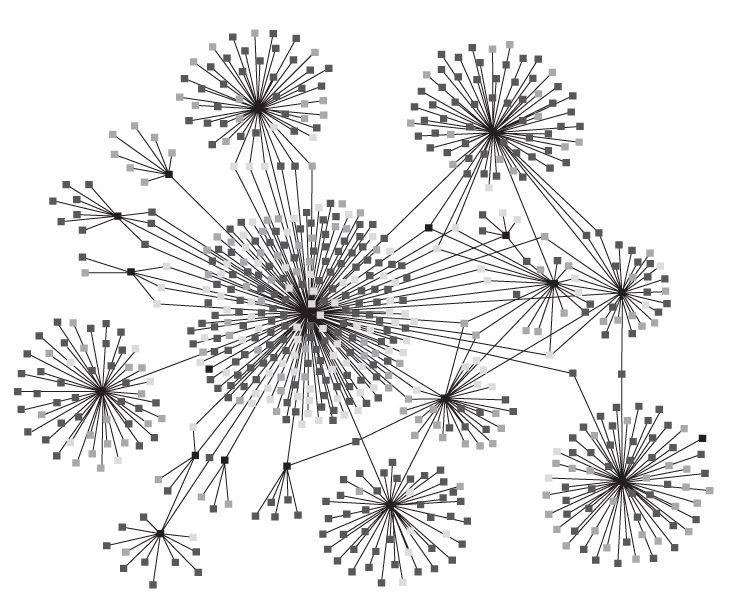

But Jim’s model assumes that neural activity is not evenly distributed. Instead, the network of the brain is built on clusters of neurons, each tightly connected within itself. These clusters then connect to other clusters and eventually form one network composed of many subnetworks—a network of networks. The beauty of this model (figure 9-1 represents the model introduced in figure 1-3), is that the brain allows the overall network to grow while maintaining equilibrium within its subnetworks.

Many things grow in this same way. Consider, for example, the infrastructure of a highway. Within cities there are many roads, and they are very well connected. But there are fewer roads that go across cities or travel long distances. What you have is a network of networks that creates (or enables) population density to increase and improves the flow of traffic within the overall network (see figure 9-2).

The same model applies to the Internet. The hardware of the Internet—computers—is connected through fiber optics and cable. These connections are not evenly distributed. Instead, clusters of computers are tightly connected (for example, computers in an office intranet), and the clusters are then loosely connected through the Internet to other clusters (see figure 9-3).

The same is true for Web sites. Researchers have analyzed connections among Web sites and found that they tend to create tightly connected Web sites within clusters that are only loosely connected to other clusters of tightly connected Web sites.

A network of networks enables population density and improves traffic flow

Source: Copyright 2008 Jupiter Images Corporation.

Take a step back and compare figures 9-1 through 9-3: it is astounding how similar they are.

The genius of Facebook, then, can be found in its network-of-networks approach. As Facebook evolves, it continues to create internal points of equilibrium within subnetworks, which it calls “groups” or (no surprise) “networks.” As the company notes, “Facebook is made up of many networks, each based around a workplace, region, high school or college.”29 Each of these networks is tightly connected, in the sense that each has many users that have strong connections to one another. Across those networks, however, the user relationships are more sparse (just as the brain’s neurons link mostly to those neurons within their subnetworks). For Facebook, this arrangement started in a controlled way—first with Harvard, then to other schools, and finally to corporations. But as Facebook opened to the world, these clusters continued to proliferate, because Facebook encouraged users to subscribe to subnetworks (see figure 9-4).

Clusters of computers connect to other clusters in the Internet

The greatest advantage of the network-of-networks approach is the ability it gives Facebook to continue to enlarge the overall network while maintaining equilibriums within the subnetworks. There are other advantages as well. One of MySpace’s problems, you may recall, was the randomness of the connections; anyone could connect to anyone else, even pedophiles to children. The network-of-networks approach helps solve this problem. Facebook leverages existing associations to control the risk of out-of-network associations.

Clusters of Web sites are connected to clusters of other Web sites

As one of the leading online social networking news sites described it, “A big difference on Facebook is that the friends you add are usually your real friends. It’s not a contest like on MySpace where everyone is trying to have the most friends. On Facebook it is about talking to the people you know and sharing things with them . . . Both sites have groups, but Facebook makes them more prominent.”30 With Facebook, you focus on your friends within your networks, and not on the overall social network.

But Facebook is not immune to the tugging and pulling of the Internet economy. Despite the protection of the network of networks approach, out-of-network expansion still happens. With more than 100 million users at last count, the dangers that have affected MySpace affect Facebook as well.31 In fact, Facebook now has its own chief privacy officer.32 It has also signed a pact with attorneys general in various states to implement features to thwart predators, stalkers, and scammers.33 But even with Facebook’s growth approaching that of MySpace, those issues of unwanted solicitation are not nearly as severe.

The real issue is whether Facebook can hold true to its network-of-networks approach. Remember that the brain as a whole eventually reaches a period of equilibrium. After this comes a massive implosion. In a recent issue of The Economist, Facebook’s “in-house sociologist,” Cameron Marlow, acknowledged that the average user only has about 120 friends, of which only 7–10 are close friends.34 This corresponds closely with two phenomena of the brain: first, the Dunbar number, a limit of roughly 150 on the brain’s capacity for relationships; and second, Miller’s magic number 7 (+2), which as we discussed earlier, is the capacity of short-term memory.35 So what is Facebook facing? If we observe the brain, the answer is clear.

Will the Internet Implode?

We’ve seen plenty of Web sites go down by becoming too big. All networks, even the Internet, at some point stop growing. But a more macro question is this: could the entire Internet implode? Again, I call upon Bob Metcalfe (Bob, please excuse me for using you once again as a straw man).

In 1995, Metcalfe made a bold prediction: “I predict the Internet . . . will soon go spectacularly supernova and in 1996 catastrophically collapse.”36 This, from Metcalfe of all people—one of the early inventors of the infrastructure of the Internet, the CEO of 3Com, and the namesake of the networking law “Bigger is better.” Why was Metcalfe now saying that the Internet, one of the largest networks on Earth, was going to implode?

It turns out that in the early days of the World Wide Web, there were looming issues. Metcalfe based his prediction on four fundamental problems, all linked to the exponential growth of the Internet. First was that during peak times, the Internet was regularly losing 10 percent of its data and communication.37 Imagine trying to listen to someone who leaves out one word in ten every time she opens her mouth. Second and third were problems with hardware and software, respectively. Because the Internet was still in its infancy, Metcalfe argued that buggy systems were likely to cause massive problems. Finally, he was concerned about global terrorism, the kind that comes in the form of viruses.38

And there were signs that the Internet was having its share of problems. Most alarming was that global outages were rampant. Consider America Online, at the time the largest Internet service provider. By 1994 AOL was openly admitting that it could not handle the load or demand of the Internet. It had started limiting the number of users online during peak times, almost begging customers to switch to competitors.39 The problems culminated in August 1996 with a massive outage that affected six million AOL users.40 By 1997, AOL was forced to refund millions of dollars to angry users who had sued over the problems.41

In another, more alarming incident that same year, a corrupt database rendered the World Wide Web virtually useless: e-mail was shut down, and domain names could be accessed only by using their numeric alternative.42 Imagine having to visit Yahoo! by typing “69.147.76.15.”

The Internet Is Dead; Long Live the Internet

But as we all know, the Internet did not catastrophically collapse and Metcalfe had to eat his words. It turned out that the Internet was far more resilient than many people had thought. More important, the Internet became stronger and more ubiquitous with each failure. What did not kill the Internet made it stronger.

But Metcalfe was not entirely wrong (he rarely is); he just missed the scope, timing, and significance of the collapse. The Internet does have its share of problems. Networking bottlenecks, loopholes, software bugs, viruses, computer glitches, and many other concerns have caused downtimes that lead many observers to believe that the Internet will one day implode. This fear caused the U.S. government to announce in 2008 a plan to reduce the Internet’s external connections (or ports) from more than four thousand to fewer than one hundred to curb the cyber threat to national security, in what Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff called the Internet’s “Manhattan Project.”43

But all these problems, even the viruses, haven’t destroyed the Internet. And in many cases, after a brief and painful period, the Internet grew stronger. After America Online’s problems, more ISPs—including NetZero and Juno, two of my public companies—sprouted up, offering increasingly better reliability. Broadband began to have increasing penetration, allowing more users to reach the Internet faster. Access became quicker, faster, and cheaper.

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) was formed in 1998 as a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the independence and reliability of the domain name system. It quickly eliminated many loopholes, such as the database problems that rendered domain names useless in 1997.

But people continue to debate the “inevitable” collapse of the Internet.44 Each time a new pundit declares the Internet dead, the problems we face are always far greater than those that fueled previous fears. But it is because the Internet advances significantly each time it encounters and solves fundamental (or for the naysayers, fatal) flaws. When Metcalfe first made his prediction, the problem was simply the number of users coming online, primarily to gain access to e-mail. That problem caused issues, but, just as Metcalfe avowed would happen, the Internet proved resilient.

Soon after that, we saw concerns about the millennium, and the millennium came and went. Then came the flood of concerns about viruses and e-mail spam. Paradoxically, this problem propelled us to new heights with viral marketing and social networks. More recently came the flood of rich media, such as YouTube, which now processes more information than the entire Internet did in 2000.45 That problem, too, will surely be solved, but there will be others. The point is that with each new problem comes a solution and a stronger Internet as a result.

So Metcalfe was right in a way; the Internet does have its problems. But his prediction was dead wrong: a catastrophic collapse has not happened. Instead, the Internet has evolved into something far more powerful. Remember when I said that Metcalfe had to eat his words? He did so, literally. In true stoic fashion, Metcalfe put his article into a blender and drank the milky paste during a wellattended Internet conference in 1996.46