7 Sibongile Sambo and SRS Aviation

Dalila Boclin

In spite of having no experience in the industry, Sibongile Sambo dreamed of founding an aviation company in South Africa. After years as a human resources manager, she secured a small amount of money from her family and established a company to broker contracts between aviation companies and clients. Soon thereafter she started to charter flights and lease airplanes, mostly for cargo. Her background loomed large when reflecting on her entrepreneurial voyage and thinking about the importance of networking, mentoring, and leading.

Figure 7.1 SRS Logo

For some people, the sky is the limit; for Sibongile Sambo, it was the frontier.

It is hard to imagine a time when Sibongile, founder and CEO of a burgeoning aviation company, would wave at airplanes overhead, hoping some gazing passenger would see her and wave back. Her story paints a picture of how a child’s curiosity is more than a set of questions and answers, but also a seed of motivation that when nurtured with determination and passion, can flower into a life filled with success and dreams come true.

SRS Aviation, South Africa’s first and only fully empowered, Black-woman-owned-and-operated airborne services business, flew its first flight in 2004. However, its foundation was laid years before the idea of a woman-owned corporation was even legal in South Africa. Sibongile grew up with a curiosity about airplanes—from how they were built to where they were going—fueling an aspiration to one day be more than just a spectator on the ground. Early in her life she began to chip away at the boundaries between herself and aviation. She laughed as she reminisced about her teenage demands on her parents: “I would actually force them to put me on a plane once a year so I could have a ride on an airplane.” Those rides, she claimed, provided the momentum that carried her passion and interest for airplanes into her adulthood.

Background

After the treacherous reign of apartheid, Nelson Mandela dedicated his presidency to reforming South Africa. He worked to rectify social injustices, grounded in the nation’s infamous past, and produced sweeping social reforms. His government did not try to simply overwrite the nation’s harsh past; rather, in establishing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Mandela attempted to peacefully incorporate apartheid’s history and influence into South Africa’s national narrative and identity. The TRC’s success is evident in the people: after 1994 political violence decreased dramatically and had virtually disappeared by 1996.1

The African National Congress inherited remarkable political, economic, and cultural challenges when it assumed power and took over from the tyrannical apartheid government. In 1994 South Africa was a country marked by racial segregation, unemployment, widespread poverty, and poor health and education. Since then the country has made incredible strides in improving economic and living standards.2 To meet the enormous challenges, the Reconstruction and Development Program was created to improve living conditions and integrate marginalized groups into the population, providing housing and basic civic services, education, and health care to disadvantaged individuals.3

In an attempt to revitalize the South African economy, the new government paired this domestic social spending with a pronounced commitment to neoliberal free markets and privatization through the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy.4 GEAR reduced the budget deficit and stabilized inflation, giving birth to a “healthy, robust, and resilient” banking system and providing the nation with the stable financial infrastructure it needed to flourish.5 Despite these gains, formal employment issues of limited opportunity and mobility for the black population, as well as the racially biased distribution of the country’s wealth, continued to plague the nation.6 To combat this inequality, South Africa passed the Black Economic Empowerment Act (2003)7 to try to assimilate the black community into South Africa’s growing market. Following the fall of apartheid, South Africa embarked on a new chapter in its history: from social welfare to economic enfranchisement, the nation reborn was able to nurture its people and produce stunning achievements such as the case of Sibongile Sambo.

Starting Slow

Sibongile first attempted to break into aviation as a flight attendant but was always limited by the height minimum most airlines required. As luck would have it, her first job offer coincided with her first cabin-crew application. In 1997 South Africa’s national airline offered her a position as a flight attendant on domestic flights on smaller aircraft with smaller cabins. Following advice from her family, she declined this long-awaited opportunity and decided to fall back on her degree in human resources, reserving her true goal for a later date.

Sibongile spent the next 7 years in human resources, working for SA Telkom and DeBeers, until the time was ripe for her entry into the aviation industry. In 2003 the post-apartheid state passed the Black Economic Empowerment Act, enabling people from previously disadvantaged backgrounds to enter and participate in economic life as entrepreneurs. Through the Women’s Economic Empowerment Policy, which aimed to economically enfranchise South Africa’s poorest group—its women—Sibongile felt ready to break out not only from human resources, but also from life as an employee.

Taking off

In 2004 Sibongile invited her sister to be a partner in her quest to own an aviation firm. Investing in aircraft, however, required tremendous amounts of capital, to which neither Sibongile nor her sister had access. Sibongile did not take on any formal debt to finance her project; rather, she relied on the people who had always supported her life-long dream: her family. Sibongile’s mother and aunt lent her the money she needed for SRS to take off. Still, with such limited funds and no experience, she was not disposed to buying or leasing her own planes. Rather, this small family loan enabled her to broker contracts between aviation services and those with air-transport needs.

SRS found its first opportunity with a government tender, which invited aviation firms to bid on a contract for cargo transport. The contract was ceded as a joint venture to SRS and another firm. Although a collaborative project appeared as a golden opportunity to wade into the industry, the other firm soon withdrew from the contract, leaving an untrained Sibongile to learn the contracting process on her own.

It was very challenging, I had to learn the different background operational needs before a flight. I had to call around and find out from different people what I needed to do. Even the clients themselves assisted me because they had run [similar] contracts before.

Sibongile reflected on the challenge of this initially stressful situation as a tremendous learning experience that quickly gave her the knowledge she needed to navigate the industry.

Sibongile could have entered into aviation cautiously by becoming a flight attendant and learning gradually through observation, but her journey led, instead, to a bold entry as an owner with her own agency. Listening to her story of how she learned the process of chartering flights, it becomes clear how that same initiative was responsible for propelling her along the steep learning curve of the aviation industry. Neither the industry nor her company could accommodate a slow trial-and-error learning strategy.

I had to actually spend time with different people who were willing to teach me how to run this business. I had to ask around in the industry. Some contractors didn’t want to help, but others were more than willing to assist me. It was a matter of approaching people.

These informal teachers helped Sibongile learn the details of organizing a flight: from giving her leads to telling her which clearances she needed and where and how to get them, to knowing how much fuel a particular type of aircraft needed, these informal mentors guided SRS through a smooth take-off and landing.

Finding a Niche

SRS operated a model different from conventional airlines by tapping into the economic potential of airplanes on the ground: “An aircraft on the ground is money down the drain,” Sibongile said. SRS evolved from its earliest model of brokering contracts, to leasing airplanes as it needed them. Most of SRS’s contracts involved moving cargo, which, Sibongile explained, returned a greater profit in a shorter time, and with less of a headache than moving people. As a result, SRS did not generally encounter competition with commercial airlines; rather, their models complemented one another, as SRS employed standing aircraft that would otherwise be absorbing money. However, SRS did contract to transport people when returns were high enough: a small percentage of the business was contracted with exclusive travelers, who chartered SRS’s private jets rather than purchasing a first-class seat with a commercial airline. This type of contract varies more compared to standard cargo transport: since the economic downturn in 2007, SRS has lost some of its business chartering private jets, as people have opted more prudently for first-class tickets. Cargo, on the other hand, has remained relatively stable, experiencing only a minor decline in 2007, with contracts resuming relative normalcy in 2008.

After merely a year of brokering flights, Sibongile’s eager entrepreneurial spirit emerged again, and so began the first steps of her company’s growth. SRS managed to accumulate capital early on by maintaining very low overhead costs, with only four employees and no office space. Sibongile applied for licenses to become a full operator in the industry, which would authorize SRS to actually contract and pilot its own flights, promoting it from a go-between to a true player in the game. As a charter company, SRS had not been responsible for the flights themselves, but was concerned mainly with marketing, securing clients, and negotiating with licensed airlines and, ultimately, applying a mark-up and handing off the client. With Pat 121, 135, and 127 licenses, Sibongile’s company leased aircraft under its own title and bore responsibility for all the logistical arrangements, from managing fuel to pilots’ learners’ permits. Although SRS progressed mainly to using leased aircraft, from time to time it provided some purely brokering services. Sibongile hoped to eventually move to a Fleet Management Model, by which she would contract with various fleets to maximize the utilization of their aircraft. Instead of leasing individual planes according to demands for transport, larger airline companies would contract with SRS to manage their fleets, in full or in part, out of South Africa. With more aircraft under SRS’s control, the Fleet Management Model would grant Sibongile much greater leverage in negotiating the comprehensive costs of commissioning a flight.

SRS’s clientele ranged from corporate or government work, to heads of state, to animal lifting, and beyond—”Anything and everything an air plane or helicopter can do . . . besides military work!” The majority of her contracts were made with the public sector, moving mostly cargo and flying within the African continent. SRS had no legal boundaries to what or where it could fly; 90 percent of its business took place predominately within the African continent, the other 10 percent comprised occasional flights to Europe, the United States, Asia, or the Middle East.

Sibongile’s unique attitude and ability facilitated her success as an entrepreneur.

I didn’t fear anything. Inside, I was confident that I wanted to get into aviation. I love it. I’ve done enough research, and I think I would be able to make it in the industry. No, it wasn’t easy, but because of the love and passion I have, I’ve persevered.

Resources Scarce and Plentiful: Financial and Human Capital

During her 7 years working as a human resources manager, although technically an employee, Sibongile assumed a leadership role and always worked above the standard, winning awards and recognition for her exceptional work. However, what stood out most, even as she was describing her time as an employee, was that she regarded it not as a deviation from her true goal, but as a constructive and integrated experience on the path toward aviation. This unique openness to learning and growing distinguished Sibongile as a natural leader. “Taking up that corporate job in 1997 in HR was a very good decision, because I do believe that I needed that corporate foundation to venture into entrepreneurship.” She learned many critical skills about how best to manage people and decode human behavior. “When you run a company, your biggest assets are the people that work for you. My career in HR actually helped me to transition into an entrepreneurship role.”

Moreover, working in human resources also gave Sibongile the opportunity to learn about herself. “I discovered that I’m actually more of an entrepreneur than a corporate person, and I came to that conclusion because of the natural characteristics that I have.” Every year she discovered qualities about herself that magnified her desire to eventually have her own aviation firm.

I come up with ideas very quick[ly], I see opportunities where most people might not necessarily see an opportunity, and I really get frustrated when I have to do one and the same thing all the time. I get frustrated when I come up with a new idea, and I want that idea to be tested and implemented, but it just gets blocked without even testing.

Ultimately, Sibongile learned as much as she could from human resources until she felt it was stifling her growth: “I was not being given an opportunity to unleash my full potential.”

Not everything came as naturally as Sibongile’s ability to lead. Aviation is a very challenging field and particularly capital-intensive. “One of the biggest challenges which we are still faced with today is capital and cash flow within the business.” Despite the post-freedom economic reforms, entering the market was by no means seamless. “We were more like a guinea pig, I would say, within South Africa, as a small company looking for a big loan.” Financial institutions would react with reservation to Sibongile’s plan:

“Aviation is risky,” they would tell us. We’ve still never had any official funding, but because of my passion and my love and my vision for this business, I decided that I was not going to let that stop me from achieving my dreams and my goals.

Access to credit remained especially difficult for black women. Only 38 percent were bankrolled, compared to 44 percent of black men, 91 percent of white women, and 94 percent of white men.8

Sibongile met this challenge with the true resources she had on hand: She created a network of family members and friends willing to lend her money, promising to pay them back with interest within a reasonable period of time. SRS continued to rely on that lifeline. “It is not at all the most convenient way of running a business—it’s very stressful and cumbersome to follow people to get them to lend you money.” Business growth did not ameliorate but, rather, exacerbated this issue: the more flights SRS had on order, the more money it needed to operate the business. There was an even greater demand for money, and still investors were weary.

Despite Sibongile’s resourcefulness, SRS had to turn away some projects because the company lacked sufficient capital. However, Sibongile did not see this financial model as conclusive for SRS.

The network hasn’t stopped me from looking for bigger investors. Right now I am working with consultants to package the company to attract investors. I’ve waited this long to create [a] strong foundation and something that is attractive to the investor: now, we’re ready to go out to formal financial institutions [and] private or organizational investors to look for funding.

In 2007 Sibongile began strategizing with an external board of directors— comprising financial consultants, legal professionals, and marketers—to plan and direct the expansion of SRS. Although she was not ready to disclose any specific plans, Sibongile saw expanding her presence outside Africa as a possibility for growth. Her business flourished in Africa, where there were still a relatively limited number of aviation firms. Sibongile noted that there were several similar companies, but not that many—especially compared to the United States. “Competing with the American market would be a huge, huge challenge,” she said; but her ambition enabled her to see beyond the horizon: “but I’d like to enter eventually into that market.” Sibongile and her directors did not see any major challenges ahead and saw the sky only as opportunity.

Despite its optimistic outlook, SRS continues to face some significant challenges. Sibongile noted that her work relied heavily on contracts with the public sector, and she was trying hard to engage more private clients. Despite SRS’s tremendous success, without any official credit or investors, expansion was a relatively slow process. In addition, a capital-intensive strategy would have invigorated the company as a competitor in Western markets. Sibongile was not discouraged, maintaining an attitude and approach that seemed assured of SRS’s future promise and success.

Although SRS made a stunning entry into the industry, challenges waited behind the gates as well.

Aviation is a very community-based type of industry. People know each other globally, and penetrating the industry is not exactly very easy. Most people saw [my entry] as very awkward, and initially, people never took me seriously. I had to prove myself more than ten times.

Ultimately, Sibongile got her message across: “I told them I’m here, I’m here to stay, I’m here to grow this business, and I’m here to make changes as well, because I’m young, I’m very innovative, and I want to bring a new spice into the industry.”

In addition, the aviation industry did not have many young, female, or black entrepreneurs. Sibongile recognized that she faced some discrimination despite her skills and knowledge. “Discrimination is something that I don’t think can just disappear overnight. There are some contracts that I didn’t get purely because I don’t go play golf with some of the guys.” At times, some of her secured contracts were hampered by racial tension: “I have partnered for some of the work with other male-owned businesses, and I have found that most of them would really take advantage and want to run the show [and] deliberately exclude us from participating on the contract.” Although these incidents occurred infrequently, they echoed South Africa’s divided past and prolonged a turbulent racial environment.

Sibongile broke these barriers by ensuring she always had the best tool at hand for this industry—knowledge. She had to study quite a bit to keep herself informed, to learn the lingo and jargon of the industry, and to actually understand the ins and outs of aviation.

In the end, [it] doesn’t matter [about] the color of your skin, how tall or short you are, or where you come from[;] what matters in this business is the amount of knowledge that you’ve got and the ability to execute it. I really strive to make sure that I empower myself with knowledge and the ability to run this business.

It is not a common feat to be a strong woman in South Africa, but Sibongile felt that it was not only her dream that she had carried since childhood, but her strength as well.

I guess my background actually gives me that platform to become a strong woman. I started living away from my parents from the age of 5 or 6 years old, which gave me a lot of independence. For high school, I went to a girls-only boarding school. I think those things have given me the confidence and also have actually shaped those strong characteristics that I have.

Moreover, Sibongile always had strong women as role models. “My mother and my aunt are very strong women as well. They both lost their husbands very early, and they took care of us as single mothers. For me, managing in an environment that is very male dominated just comes natural. I think it just comes from a confidence and willingness to learn, but also from the willingness to make mistakes, learn from them and move on.”

Entrepreneurial Reality: Life on the Ground

Facing the world as an entrepreneur inevitably brought personal challenges as well. First, Sibongile had to face the new reality that, “If I don’t work, there’s no food on the table.” But she averted this uncertainty by adding discipline and structure to her passionate goal. “I’ve tried my best to be disciplined. I try to get to work as often as possible, working like someone who works for someone else, from 8:00 to 5:00.” But sometimes, discipline and determination themselves could be an obstacle: “If I feel sick, and I need to take time to rest, unless I really need to, sometimes I try to avoid that. Sometimes I push myself maybe way too much because I just want to see this business working.”

Although Sibongile’s confidence in herself as a woman and encouragement from her family were key to her success, at times they posed awkward stumbling blocks to SRS’s operation. “Giving [my family members] duties sometimes has been a challenge.” “You know,” she said giggling, “acting as a boss, giving instructions to my elder brother.” Moreover, juggling the roles of mother, business owner, sister, and friend took a toll on Sibongile’s personal life. “I have lost quite a lot of friends because as soon as I started running a business, I needed to spend time with other business people.” Other times, being independent cut into her family life. “I know there are times when my son, who’s just seven years old, needs me, [but] I would have something for this.” Sibongile gave an example of how being a responsible CEO could compete with being a mother: she cited a time when she was to attend her son’s concert at school, but because she had a meeting with a potential investor, who was leaving the country first thing the next morning, she had to miss the opening night. Although she was able to see the show on a different night, her story provided some perspective on how she negotiated compromises between her lives as a mother and a businesswoman.

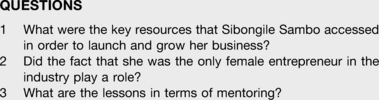

Being an entrepreneur challenged Sibongile in the industry, at home, and within herself. But what characterized her as a truly comprehensive leader was her keen recognition and ability to derive strength and knowledge from others. Despite her tremendous success, Sibongile still looked to her heroes for guidance, from former President Mandela to her mother, to both American and African women entrepreneurs, and to her clients. The diversity of her role models was indicative of the broad personal development Sibongile was constantly striving for. She cited President Mandela’s “heart of umbunto”—compassion for other people—as a quality she truly admired, and she has been lucky enough to have chartered flights for him a few times (see Figure 7.2).

I’ve moved quite a lot of people, from Harry Belafonte to heads of state. And those people are my role models too. I find that most of my clients are people I can actually learn from, and therefore I draw a lot of strength, energy, and knowledge from them.

Figure 7.2 Nelson Mandela and Sibongile Sambo

Source: Reproduced with permission from Sibongile Sambo, December 10, 2009.

Sibongile had also been paired with Louise Francesconi, former president of Raytheon, through an international mentorship program that matched women from developing nations with American businesswomen. “The experience has been so amazing. The mentorship that I’ve gotten and I’m continuing to get from her—it’s brilliant. I talk to her either by phone or by email, it’s a really, really empowering program.”

Sharing her Strength

Having personally experienced the benefits of mentorship, Sibongile took on another personal goal, to share the aviation industry with those with the potential to pilot its future—namely, South Africa’s children. She was engaged in a project to not only teach students from local schools about the opportunities in aviation, but also show them first-hand the promise of an empowered, determined individual. This project involved visiting SRS at its headquarters in Randburg or meeting with Sibongile at one of Johannesburg’s main technology centers, to provide students with a real-world glimpse into the exciting opportunities in science and technology. Sibongile wanted to encourage children to focus more on mathematics and science and, obviously, to consider aviation as a career option. She wanted to package this as a formal social entrepreneurship initiative that could gain government funding and be extended to more students. Her own personal experience of realizing her dream not only made her an incredible role model for children, but also gave her a unique insight into the importance of inspiring children and adults in a way that was more personal than a policy and more fulfilling than money or profits.

Aviation was a male-dominated sphere: Sibongile was the only female CEO in South African aviation, although the industry saw women entering from different angles, from airport and traffic management to more technical jobs such as aircraft engineering. Since her childhood as an entrepreneurial dreamer, Sibongile persevered to realize her dream, appreciating every chance and challenge as an opportunity to expand her knowledge and personal strength. She and her company have traveled far and shocked the world with their success. They continue to plan, fly, and dream as if only the sky was the limit.

Notes

1 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, “Background Note, South Africa” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of State). http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2898.htm (accessed January 25, 2009).

2 Vivek Arora and Luca Antonio Ricci, Post-Apartheid South Africa: The First Ten Years (Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 2005), p. 2.

3 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, “Background Note, South Africa.”

4 Ibid.

5 Arora and Ricci, Post-Apartheid South Africa, p. 3.

6 U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, “Background Note, South Africa.”

7 Republic of South Africa, “Government Gazette, Broad-Based Economic Empowerment Act.” (Cape Town, Republic of South Africa) www.info.gov.za/view/DynamicAction?pageid=545&sdate=%202003&orderby=act_no%20desc (accessed January 25, 2009).

8 The World Bank Group, “Flying High: SRS Aviation,” Doing Business: Women in Africa (2009): 19.