14 Maha Al Ghunaim

Building an Investment Bank through the Crash

Adrian Tschoegl

How can a woman leading an investment bank in an emerging economy such as Kuwait navigate the turbulent waters of the global financial crisis? Maha AlGhunaim headed a multi-billion dollar financial powerhouse—the only woman to do so in the Middle East—and grew it domestically and internationally. Her unique leadership style, corporate governance, and approach to strategic thinking proved essential to meet the challenge.

On June 28, 2008 Maha Al-Ghunaim, chairperson and managing director of Global Investment House (Global), the investment bank she had built with four friends, was on top of the world. The company was celebrating its 10th anniversary. In the space of 10 years it had grown from an entrepreneurial US$50 million company to a company with a market capitalization exceeding US$5 billion. It had a regional and international client base of over 6,500. In October, Global reported pretax profits of US$386 million for the first 9 months of 2008, an increase of 66 percent from the year-earlier period. Global’s assets under management surpassed US$10 billion.

Global had grown from one office in Kuwait City to offering stock brokerage or investment banking services in Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Oman, Jordan, Tunisia, India, Qatar, Hong Kong, Pakistan, Sudan, Yemen, Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. At home, Global had just moved into a new US$70 million headquarters building in Kuwait City, leaving behind its former modest and aging head office building a few blocks away.

Global’s shares were listed on the Kuwait, Bahrain, Dubai and London stock exchanges. In May 2008 it had just had a successful offering of global depository receipts (GDR’s) in London, raising £600 million (US$1.15 billion) in equity. This was the first such offering by a Kuwaiti company. The company was highly respected. In June Euromoney had named Global the “Best Equity House in Kuwait” for the fourth year in a row and Asiamoney had named it “Best Investment Bank in Kuwait” for 2008.

Maha herself had become chairperson of Global in March 2007 when Anwar Abdullah Al-Nouri, who had been chairman since the company’s founding, had decided to step down from the position for personal reasons. She was the only woman at the head of an investment bank in the Middle East, and one of the top bankers in the Gulf. She had reached this position not by inheritance but rather by her own efforts. She had first risen through the ranks of the Kuwait Foreign Trade Contracting and Investment Company (KFTCIC), a government-owned investment firm, despite meeting some resistance from men who thought that a woman’s place was at home. Then she had the courage to found her own firm.

Maha’s success had also drawn media attention, and she won a number of accolades. She received the “Banker Middle East Industry Award 2008 (BME) for her outstanding contribution to the financial industry.” In September 2008, the Wall Street Journal named her number 43 on its list of 50 “Women to Watch.” Forbes (U.S.) ranked her 91 on their list of the “world’s 100 most influential women,” and Forbes (Arabic edition) ranked her second in its list of the Arab world’s fifty best businesswomen. Though she had not sought the honors, the press was now proclaiming her a role model for Arab women and women in the Islamic world.

Maha Al Ghunaim’s Professional Background

Maha was born in 1960 and is one of eight children, four girls and four boys. (She also has one half-sister and four half-brothers through her father’s first wife.) Both her parents believed in education for all their children, girls as well as boys, and Maha attended a French-language boarding school. Her mother was educated and spoke English as well as Arabic. Maha describes her mother as independent and strong. Most of Maha’s siblings went into engineering. She herself loved math and was in the top ten students in Kuwait in her year.

In 1978 Maha went to college in the United States. She chose San Francisco State University solely because a friend was going there. At the time she did not realize that the university was not among the more prestigious in the United States. Still, Maha graduated with a degree in math in 1982.

After graduating Maha returned to Kuwait and looked for a job. One man she remembers well suggested that she not bother: women should stay in their parents’ home till they get married, and then should stay in their husband’s home. Some years later Maha became this man’s boss’s boss.

Maha joined KFTCIC, which was not only the largest of the three Kuwaiti investment banks, but also 80 per cent government owned (in time the Kuwait Investment Authority came to own 95 per cent of its shares), and the only one to show an active interest in marketable securities, where it played a key role in trading bonds and shares in international markets. Working there provided her with an opportunity to learn. KFTCIC already had a good reputation for competence and focused on providers. The company was looking for educated staff and gave her the opportunity to choose her assignment. She began as a dealer in marketable securities, executing transactions, and then became a portfolio manager. This gave her the opportunity to travel to visit companies to see how they operated, which was itself an education.

In 1988 she became vice-president for portfolio management. She became a member of the asset allocation committee and a member of Al-Kharejeyah Umbrella Fund. In 1995 the Kuwait Investment Authority combined KFTCIC with Kuwait Investment Company (KIC) under the KIC name. Maha was appointed assistant general manager of asset management at KIC and was responsible for the local and international markets.

By 1998 Maha had arrived at the point where the next logical step was to found her own investment bank. She had had a model career in which she had worked her way up through the major areas of investment banking, and so had a good understanding of what was involved.

She also saw an opportunity. There was a need for a local investment bank that would meet international standards. There were few local competitors, and no foreign firms. The foreign firms would send in representatives from time to time to tout their latest product, but these representatives did not know the area or the clients. As a result, there was no one who produced equity research, or underwrote bonds, traded fixed income, or offered money market and bond funds. Maha decided that she would build a firm that would do all of this. The key to success would not lie in taking market share away from competitors but rather in introducing new products that would make the pie larger.

Maha believed that she had to work harder than her male colleagues. She was quick to credit her husband and family for their support. Her husband is the chairman and managing director of another company and understood the pressures she faced. She always worried about how the demands on her time of building and leading an investment bank would affect her children. When asked, they reassured her that they understood that her drive was a core part of her.

As far as acceptance by clients was concerned, Maha acknowledged that “first, clients look at you as a woman.” But, as she puts it, the key issue is, “Are you competent? Investment banking is a field where numbers are the metric.” Performance is measurable and visible, and clients respond accordingly.

Organizing and Leading Global Investment House

When Maha decided to establish her investment bank she knew she needed a management team. She brought in four people as co-founders. They were:

- Mr. Bader A. Al-Sumait, who had 19 years’ experience and would be in charge of investments locally and in the member countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council;

- Mr. Omar M. El-Quqa, CFA, who had 16 years’ experience and would be in charge of corporate finance and treasury;

- Mr. Sameer A. Al-Gharaballi, who had 16 years’ experience and would be in charge of investment funds; and

- Ms. Khawla B. Al-Roomi, who had 16 years’ experience and would be in charge of personnel and administration.

Maha brought Mr. El-Quqa, Mr. Al-Gharaballi, and Ms. Al-Roomi, with her from KFTCIC. In appointing Ms. Al-Roomi to a top management position Maha started as she meant to go on—giving women positions of responsibility. When Global started, it was a pioneer in hiring women for leadership positions in investment banking, though seeing women in responsible positions was more common in commercial banking. Today, Global is only slightly above average in giving women responsibility as the other firms have caught up. With the team in place, there was still one additional leadership role that needed filling.

One of Kuwaiti culture’s distinctive features is the diwaniya. Originally, among the Bedouin, a diwaniya was the section of the tent in which male members of the family would meet with male visitors, separated from the women and children. In old Kuwait City, the diwaniya was the reception area of a house where a man received his male business colleagues and guests. Today diwaniya has come to mean both the reception area and the assemblies that take place there. For a Kuwaiti man, visiting or hosting a diwaniya is an important part of both social and business life.

When Maha and her colleagues established Global, she knew that she needed someone to represent the bank in the diwaniyas of Kuwait. She therefore invited Anwar Abdullah Al-Nouri to be chairman of the bank, a position he would hold for the next 9 years. His acceptance of the chairmanship gave Global immediate credibility. His role was neither symbolic nor only Global’s public face. Maha referred to him as “The last gentleman on Earth.” He provided the young founders of the bank with a voice of experience and wisdom. In addition to Mr. Al-Nouri (chairman) and Mrs. Al-Ghunaim (vice chairman), the board included Mr. Khalid J. Al-Wazzan, Sheikh Abdulla Al-Jaber Al-Sabah and Mr. Marzouq N. Al-Kharafi as board members.

Maha was able to establish the company within two weeks. The shares were over-subscribed, a testament to her reputation, that of her family, and that of her team. As a result, she was able to choose her shareholders and board of directors. Her initial board remained unchanged until 2007 when Anwar Abdullah Al-Nouri stepped down from the chairmanship. (Then Maha became chairperson and managing director, and Mr. Khalid J. Al-Wazzan became vice-chairman. An Englishman, Mr. Alan H. Smith, joined the board as an independent member.)

A last issue was to pick a name. Stuck after considering and rejecting a number of ideas, Maha turned to a sister, who suggested “Global” as a modifier of “Investment House.” “Global” embodied an ambitious goal, and so “Global Investment House” was born.

Business Strategy

Before the crash, Global built its growth on five areas: investment banking, brokerage, asset management, real estate and principal investments. It used research to build its brand name in new markets before it launched new products and operations. Also, research supported asset management, broker age and investment banking. Investment banking created investment opportunities for asset management clients and could suggest opportunities for principal investments. Brokerage benefited from both the strong research base and from the asset management client base. For the purposes of this case, the discussion below looks only into some aspects of asset management and principal investments.

In the asset management area, most of Global’s initial clients were its shareholders. They were also almost entirely male. Then between January 2001 and June 2005, Global started offering annual seminars for women in Kuwait. Global saw an opportunity in educating women to make decisions for themselves. In time, the wealth management client base in Kuwait grew from being about 3 percent women to about 30 percent. Global now plans to introduce such women’s seminars in Saudi Arabia and elsewhere in the GCC area. Global’s existing wealth management clientele in the Gulf is predominantly male but as in Kuwait, Global sees an opportunity in catering for women.

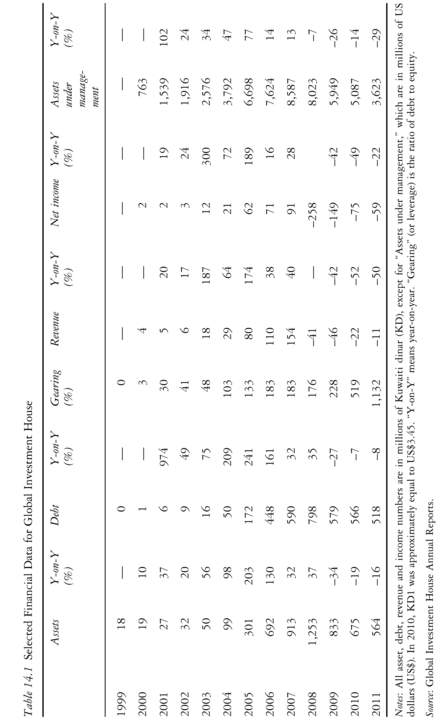

From 1999 on, the number of asset management clients grew at about a 22 percent per annum cumulative average growth rate, reaching about 7,600 in 2009. The amount under management grew at a cumulative average rate of 19 percent per annum, reaching US$5,087 million in 2010, after having peaked at US$8,587 million in 2007 (see Table 14.1).

Institutional investors accounted for about 79 percent of the assets under management. Retail investors accounted for about 21 percent. Global had a good history of client retention. One reason for this was that Global was the first investment bank in the region to have a client relationship department. Furthermore, Global kept staff numbers in line with the growth in clients and so kept service levels consistent. As a result, 85 percent of Global’s clients from 1999 were still with Global as of mid-2009. In mid-2008, 8 percent of Global’s clients had been with Global for over 8 years. Some 26 percent had been with it for a year or less.

The bulk of the assets under management were in in mutual funds. Global’s best performing fund was the Global 10 Large Cap Index fund,

which invested in the ten largest companies listed on the Kuwait Stock Exchange. However, as an index fund, the fund simply depended on the Kuwaiti stock market for its performance. Its only innovation lay in bringing index investing to Kuwait. What was more interesting was Global’s Global Buyout and Global Opportunistic private equity funds. Furthermore, Global has launched Global al-Ma’amoun fund in 2001, a unique income fund in the Kuwaiti market with two classes of shares, class A being owned by the Kuwait Investment Authority and class B by the public with a priority for the latter to receive the first 4 percent of the fund’s yearly return. In return, class A shareholders get a higher share of the returns should the fund generate over 4 percent annually.

Already in 1999 Global put a little money into principal investments, that is, investments on its own behalf rather than for clients. The investments grew modestly through 2004, with growth becoming rapid from 2005 on, when annual gross income was 38 percent. In subsequent years, income averaged about 19 percent annually, before dropping to 12 percent (annualized) by the end of the third quarter of 2008.

To support this growth Global started borrowing. As it did so, the ratio of its debt to equity (its gearing or leverage) climbed. Not only was Global now more highly geared (levered) and more dependent on principal investments for its profits than in its early days, but the debt was relatively short-term.

In the Gulf, “long-term” meant a maturity of 2–3 years as medium term notes (maturity of 5 years or so) were not yet common. This 2–3 year maturity of its recent debt meant that Global had to refinance frequently, and in ever larger amounts. Furthermore, it was in the nature of principal investments holdings that they were not liquid. And these factors were the source of the start of the crisis, when Global could neither refinance to make its principal payment nor sell assets, and so had no alternative except to default.

Impact of the Financial Crisis

In 2007, oil prices started to climb steeply. The pace accelerated from March 2008 and prices peaked in August 2008, before starting to fall sharply. The run-up in the price of oil triggered problems in mortgage and lending markets in the United States. Much of the growth in residential construction in the U.S. was occurring in suburbs in California, Nevada and Florida. High oil prices discouraged people from buying in areas where they would face long and thus expensive commutes, reduced households’ ability to service their debts, and caused them to tighten their budgets and reduce consumption.

The housing price bubble in the United States had already peaked, and started to collapse in 2006–07. This led to the crisis in the sub-prime mortgage market. When the housing market began to deteriorate and the ability to obtain funds from investors through investments such as mortgage-backed securities declined, the investment banks were unable to fund themselves. Investor refusal to provide funds via the short-term markets was a primary cause of the failure of Bear Stearns and then of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008.

Stock markets around the world, which had been falling for some time, sunk precipitously. This set off a panic in interbank markets, which froze. Banks stopped lending to each other, including short-term (even overnight) money. This was particularly problematic for investment banks, which relied on short-term financing that required them to return frequently to investors in the capital markets to refinance their operations.

Global Investment House was not immune. It had made many long-term investments that were relatively illiquid, but had funded them by relatively short term (2–3 year maturity) debt. When one of these debts came due, Global was unable to raise new debt to fund the repayment.

On December 15, 2008, Global announced that it would be unable to pay a principal payment that was due on a US$200 million international syndicated lending facility (that is, a loan extended by a group of banks). Global stated that it would continue to make interest payments, but the failure to make the principal payment meant that the firm was in default on its borrowing contract. Because debt contracts have cross-default clauses, default on one debt meant that Global was automatically in default on all its debt. Global announced that it was appointing a financial adviser to renegotiate the existing credit facilities’ terms with lending banks.

The Growing Problem

Even before the bankers arrived on December 22 to discuss Global’s future with Maha, its board and its top managers, the rating agency Fitch had downgraded Global’s issuer default rating (IDR, an estimate of a borrower’s ability to meet its financial commitments on schedule) from BBB to C, its short-term IDR from F3 to C, and its individual rating from C to E. Furthermore, Fitch had put all three ratings on Rating Watch Negative.

On January 9 Fitch further downgraded Global’s long- and short-term IDRs from C to D. Global’s KD long-term rating dropped to from C to D. Lastly, its individual rating dropped from E to F.

In April the Kuwait Stock Exchange barred Global from trading on the exchange for some days because it had failed to publish its year end results on time. Global eventually posted a net loss of KD257.6 million ($885.2 million) for the year 2008 after it had made impairment charges of KD297.4 million ($1 bllion). These impairment charges were due in large part to unrealized losses on the company’s investments. The Gulf had thought that it was somewhat insulated from developments in the rest of the world, but as matters turned out, it was not. Problems developed in Dubai and elsewhere in the GCC and even in the wider Middle East and North Africa (“MENA”) region. Equity indices in these regions fell between 36 and 55 percent, an unprecedented decline that hurt Global’s principal investment holdings.

The creditors established a steering committee to discuss how to restructure the US$1.8 billion in debt. Some fifty-three creditors appointed West LB, which had arranged two syndicated loans, to chair the committee.

A high-level steering committee chosen by Global’s creditors was in talks to restructure Global’s $1.7 billion debt. A Kuwaiti bank, representing local banks, and an Islamic bank, were also on the committee. Global, with its financial advisors, presented a comprehensive restructuring plan backed with financial forecasts, a detailed business model and an independent valuation of its assets.

Throughout the process, Maha and Global stayed in touch with the asset management clients, explaining what was going on, reassuring them that write-downs and impairment charges were only for Global’s own holdings and did not affect the funds that Global was managing for the clients.

Changing the Strategy

To return to profitability Global had to undertake a number of difficult measures. First, it instituted salary cuts of up to 20 percent and canceled all bonuses. On the operational side it closed its operations in Yemen, Iran and Iraq.

The largest change was in strategy. Principal investments had been the source of the largest part of Global’s losses. Henceforth, Global would return to its roots as a middleman, giving up acquiring companies purely for investment purposes. Although principal investments had suffered in 2008, fee income from asset management and the other activities had continued to grow.

Maha committed Global to exiting the principal investments business “in a orderly fashion” over the medium term. She also committed to using the proceeds primarily to repay Global’s debt obligations.

The first step in the restructuring of Global’s management consisted of changes in the management team. Mr. Bader Al-Sumait, who had been the executive vice president for local and GCC investments, became the chief executive officer. All the business groups would be reporting to him. Mr. El-Quqa was asked to resign.

There were also additions to the management team as featured in the annual report. In the 2008 report, Ms. Khawla B. Al-Roomi, the fifth of the founding managers, appeared as the EVP–personnel and administration, representing an elevation in the role she had occupied since Global’s founding 10 years earlier. Ms. Nawal Mulla-Hussain, who had joined Global in 2004, was elevated to the position of EVP–legal affairs, a testament to the important role that legal matters now played in Global’s survival. Last, Mr. Sunny Bhatia, who had joined Global in 2006, was elevated to the position of EVP–chief financial officer (CFO).

In 2010 Mr. Khalid J. Al-Wazzan, the vice-chairman and a member of the board since Global’s founding, left the board. His replacement as vice-chairman was Hamad Tarek Al-Homaizi. Sheikh Abdullah J. A. Al-Sabah, who also had been on the board from the start, left. The board received several other new members, one Kuwaiti, Ali Abdulrahman Al-Wazzan, and two non-Kuwaitis, Bambang Sugeng Bin Kajairi, CEO of Reem Investments, Abu Dhabi, and Junaidi Masri, of the Brunei Investment Agency.

Financial Restructuring

In December 2009 Global arrived at a debt-restructuring agreement with its fifty-three creditors. The creditors agreed to reschedule the $1.7 billion debt and entered into new 3-year loan facilities. Global also undertook to make payments to reduce the outstanding principal.

Global transferred substantially all of its principal investments into the newly created Global Macro Fund, incorporated in Bahrain, and a Kuwait-domiciled special purpose vehicle (SPV) real estate holding company (“Real Estate Holdco”). Global would continue to own both, so their performance would continue to affect Global’s financial results. Global undertook to wind down its investments in an orderly manner and apply the proceeds to repaying its debt.

David Pepper, from WestLB and chair of the Banks’ Steering Committee, added:

We are delighted by this successful outcome today and are highly appreciative of the tremendous efforts Global and its advisers, HSBC have demonstrated throughout this process. Global’s professionalism and transparency throughout this process has been highly commendable and has set precedents for other restructurings in the region.

In May 2010 Global’s shareholders approved a rights issue that would increase its capital by about 76 percent or about US$346 million. However, Maha has not implemented the capital increase.

Between August 26, 2008 and December 31, 2008, Global’s share price fell 80 percent. Between 1 January 2009 and the end of October 2010, the share price had fallen another 67 percent, with the sharpest fall coming in the first quarter or so of 2009. From then on, the share price has simply trended flat to slightly down.

In November 2011 the Kuwait Stock Exchange suspended trading in shares of Global on the grounds that the company’s losses had exceeded 75 percent of its capital. Global fought the ruling. Global is fighting the suspension, but the shares have not traded since November 14, 2011.

Then on December 13 Global announced that its lenders had agreed to defer certain mandatory minimum principal payments to June 10, 2012 and defer or waive certain covenants. Global would continue to pay interest payments as they came due, but would not have to start repaying principal. Global subsequently asked for another extension to November 10, 2012. More positively, Global won a US$250 million case against a UAE bank.

Global remains one of the most highly regarded investment banks in the Gulf. Maha is in an advanced stage in the negotiations with Global’s creditors to reach a permanent solution that will reposition Global as one of the leading financial services providers in the region, capitalizing on its competencies: loyal and experienced management and employees, its presence in major regional capital markets, and the relationship Global enjoys with its loyal clients who have shown support, especially during challenging times.

Over the years, especially during the financial crisis, Maha has shown a great level of commitment and devotion to her employees, clients and shareholders. This is key in implementing the company’s strategy moving forward, which focuses on offering services to its clients in asset management, investment banking and brokerage.