CHAPTER 8

MIND

Give them a reason

‘The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled.’

Plutarch

The mood is set. Your audience's hearts are thumping in heady anticipation. They're feeling a bias to yes, so why aren't we done yet?

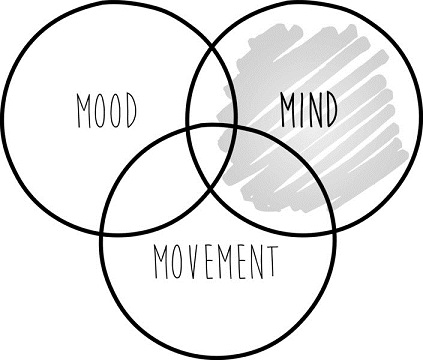

Trying to secure buy-in on the basis of mood alone is like trying to drive with the handbrake on. We might ‘feel’ like saying yes, but our rational thinking brain is in the driver's seat and it's looking for signs that this is logically the right move to make. This is the world of Mind — the second dimension of our 3M model.

To draw on a metaphor used by Chip and Dan Heath in their wonderful book Switch: How to Change when Change Is Hard, our emotional, intuitive side is like a huge elephant, while our rational, logical side is the person riding the beast. ‘Perched atop the Elephant, the Rider holds the reins and seems to be the leader. But the Rider's control is precarious because the Rider is so small relative to the Elephant. Anytime the six-ton Elephant and the Rider disagree about which direction to go, the Rider is going to lose. He's completely overmatched.’

The Rider might be small in relation to a six-ton Elephant, but it asks the tough questions and keeps us from making poorly thought through, impulsive decisions — or at least, tries to. It's the Rider who works out how to deal with complex problems that make progress hard, the sorts of things that might otherwise scare the Elephant into running away.

Of course, the Rider doesn't always get a say. We often do things based purely on intuition and emotion — sometimes for good reason (asking someone out on a date), and sometimes to our regret (losing our temper with a colleague or a loved one).

When I decided to start my own business in 2011, the Elephant was well and truly awakened. I was emotionally biased towards a resounding ‘Yes!’ But for over a year I hadn't actually made any progress on doing anything about it. What was slowing me down? I kept saying to myself, Don't rush into this Simon, work through the detail. The logical, rational side of my brain insisted that I do the sensible thing and carefully work through the pros and cons, trying to find a way to manage the risks, calculate the cashflow, determine the best timing — and so the list went on. It was a big decision and one my practical brain wasn't ready to commit to, no matter how much I felt like I wanted to.

That's why buy-in involves a mood–mind connection. Feeling and logic have to work together, to be ready to play on the same team, in order for us to say ‘yes’.

Syncing mood with mind

As much as we like to be inspired by the things we do, it's hard to justify risky decisions on the basis of mood alone. Imagine your CEO standing in front of hundreds of shareholders, announcing that the company will be opening offices in a new city just because ‘It feels right, don't you think?'

Plato described emotion and reason as two horses trying to pull a chariot in opposite directions. While that's how it can sometimes feel, neuroscientists tell us that the two sides of our brain act in elegant concert with one another.

Emotion helps us to know how to act on logical conclusions, and logic helps us to manage our emotions.

The challenge when building buy-in is to align our audience's logical thinking with the way they feel about our idea. This is particularly important in the business world, which places an enormous premium on logic and sound decision making, which is magnified by the multiple layers of managers and owners all looking to scrutinise every decision made.

The logic of ‘yes’

When you ask someone to buy into your idea or initiative, their rational brain calculates furiously whether it's a good idea or not. Is it worth it? Is it a smart idea? What's the value? Where's the proof? By working through these types of questions, they are seeking to arrive at a rational answer — what I call a logical yes.

Let's look at the two primary ingredients of a logical yes.

What's it worth?

What is the value of a stand-up desk? How about a set of measuring cups? A leaf blower? A kilo of arabica coffee beans?

If you're searching your brain for the price tag of these items as they might sell in a shop, then you're looking in the wrong place. ‘Price is what you pay; value is what you get,’ said world-renowned investor Warren Buffett. So how do we define the value of an idea?

Here's the trick: how valuable you think your idea is doesn't much matter when it comes to buy-in. The only thing that matters is what they think — that's the people you're trying to engage, your target audience.

Like beauty, value is entirely in the eye of the beholder. One person's prized antique is another person's doorstop.

At the risk of dampening the mood with an equation, value can be expressed as:

Value = Benefits – Cost

Benefits means all the ways in which your proposal or idea is good for me — the extent to which it meets my needs and drivers, and gives me satisfaction. As I sneak in a cheeky donut for morning tea, the benefits seem clear: aside from sating my appetite, I get to feel a sense of indulgence and enjoyment.

Of course, I know there's a cost, aside from the cash I just handed over. I can't seem to get the fabulous line ‘A moment on the lips, a lifetime on the hips’ out of my head. Donut confessions aside, the cost of your idea includes anything I need to give up or suffer in return for accepting your proposal. That may include risks I take on, inconvenience, diversion away from other activities, time away from family, for example.

Put yourself in your target audience's shoes: how might they see the value of your idea or initiative? In particular, ask yourself the following questions:

- What would make this an idea worth investing in? What are the real benefits to them?

- What concerns and reservations are they likely to have? What are the costs to them?

- How can I address these concerns, or how flexible am I willing to be to modify my idea or proposal to address their reservations?

- What questions do I need to ask before I can fully appreciate and understand their perception of value?

In giving thought to these types of questions, you will begin to see value not through your own eyes, but through theirs. That is the key to building buy-in.

Prove it

Even if I see value in what you're proposing, how can I be sure it will actually work? What would other people say? Will I look stupid for saying yes? How will this look if it ends up in the news? Getting your audience to a logical yes means helping them to address these kinds of questions.

Value is a highly subjective thing; proof, on the other hand, is far more objective. Proof is anchored in the opinions or experiences of others — ideally, people with the right kind of expertise and wisdom.

People derive proof from a variety of sources, such as:

- research and data, numbers and statistics

- case studies and examples of how your idea has worked elsewhere

- testimonials, online reviews and ratings that show what others think

- verification from consultants and experts.

The business world trades heavily in proof or evidence. It enables executives to show their key stakeholders that risks are taken on only where it's objectively smart to do so. Proof not only gives your audience assurance and confidence that it's wise to proceed, but also helps them to feel that they've covered their backside in the event things go pear-shaped.

In the late 1980s there was a saying bandied around the IT world: ‘No one ever got fired for buying IBM.’ This wasn't just a marketing slogan; it was an axiom invented by customers themselves. Consumers loved buying IBM because the proof that the product worked was overwhelmingly on their side. We can rest easy knowing that we've made a smart decision.

It's a wonderful thing when proof becomes a part of your brand. This holds true for all of us. Our own track record ultimately becomes the greatest form of proof we can offer.

Don't fake it to make it

Mark Twain once famously wrote, ‘There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics.’1 The fact is, numbers and statistics can often be massaged to prove even a weak argument. An even worse version of this kind of transgression is to, well, make it up. To hint that there is proof when in fact there is none may be tempting, given this ‘proof’ will often go unchallenged.

Just don't do it.

Generating buy-in is not simply a matter of convincing people to say yes. It's a matter of generating genuine, voluntary commitment. This requires people to invest in your idea and in you.

The moment you get caught playing make-believe in the world of proof, however innocent that little white lie might seem, is the moment that trust collapses, bringing with it all your hopes and dreams for buy-in.

Make sure you do your homework. Prepare to show your audience proof and evidence they may genuinely need to see to support your idea. Ask yourself these questions:

- What data or other evidence am I relying on?

- What assumptions am I making about their relevance to my own idea or proposal?

- How can I best share my sources of proof in a way that allows my audience to fully understand my thinking and reasoning?

- What other sources of proof might my audience have seen, or might they want to see?

Create, don't fabricate

Of course, proof may not always be available to you. Perhaps your idea is unique and so new that there's nothing to point to. What do you do then? You create proof — which does not mean you fabricate proof! Conduct your own mini-laboratory or research experiment that enables you to establish proof of whether or not your idea will work.

Companies engaged in rapid innovation do this all the time: they practise a ‘test and learn’ philosophy. This kind of approach accepts that truly innovative ways of doing things will lack solid proof, but that shouldn't prevent the company from at least giving it a try.

Take, for example, global online travel company Expedia. According to CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, the company's test and learn culture is based on the notion that, ‘regardless of how senior you are, if you have an idea, it will get tested and live or die based on that’.2 With this kind of approach, the proof, as they say, is in the pudding.

This can be especially powerful when done in collaboration with your target audience. Consider asking them, ‘What's the simplest way we can test the merit of this idea so you and I can make a decision about whether to take it further?’ Even in situations where you have brought established proof to the table, switching to this kind of collaborative approach can work well to keep the conversation moving.

Go slow to go fast

‘Go wisely and slowly. Those who rush, stumble and fall.’

William Shakespeare

Now you've thought about what value you're offering to those you're seeking buy-in from, and prepared the proof that will help convince them that your idea is a smart one, it would be easy to think you've got buy-in in the bag. All I have to do now is swoop in, stick a pen in their hand and ask them to sign on the dotted line, right? … Wrong.

You may be sold on your idea, but your target audience is still at first base … if they've even stepped onto the field yet.

Your job is to help them move along a path of thinking that allows them to see the value and the proof in the same way you do. But they will have questions. They'll have doubts. They may need time to think things through, to voice objections, to think some more, to spit the dummy, to sleep on it overnight and then change their mind. That all takes time. If you try to fast-track that process, the risk is that they become suspicious of your agenda or disengage from the whole idea. None of us likes the pushy salesperson. We all have finely tuned ‘foot in the door’ detectors.

Your job is to escort your audience along a path of logic that allows them to join the dots themselves. Go slow to go fast.

At the same time, you can't afford to allow things to drift aimlessly on a cloud of indecision. You need to drive their thinking towards a conclusion — even if in some situations that means a ‘no’.

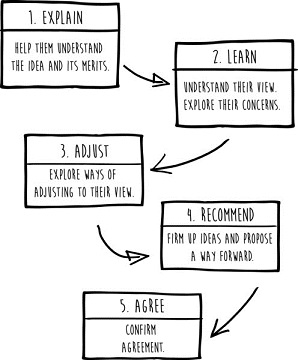

To guide you along the path to a logical yes, figure 8.1 (see overleaf) shows five sequential steps to follow.

Figure 8.1: the path to a logical yes

Step 1: Explain

This is your opportunity to open the conversation about your idea with a clear and compelling explanation. Knock 'em out with your conviction! Demonstrate the Big So What. Set the right mood and tone. Show them the value and the proof. Now is the time to put into practice all the crucial elements you've learned so far in this book.

Make sure you are specific and clear. This is not the time for fluff. Nothing clouds the path to a logical yes more than ambiguity. There's a big difference between ‘I'm seeking to create a more innovative culture’ (Okay … so what do you want from me?) and ‘I'm asking every team in the business to participate in a half-day workshop designed to identify how we as a business can become more innovative’.

Part of the art here is to distil your explanation to the most salient points. As a basic rule, you need to get to the second step — Learn — as quickly as possible. So ask your audience if anything is unclear and if they need you to explain more, rather than drowning them in detail they don't need at the outset.

Your goal in this first step is not to get your audience to actually agree to anything (yet) — only to present your proposal in the best possible light before you hand the metaphorical microphone to them. Remember, this is only the first of five steps. Less is more!

Step 2: Learn

All that matters in this second step is what they (your audience) think. Set aside your ego and let them talk. Remember our tips for engaged listening in chapter 6? Now's your chance to listen like a pro and learn from them. Kickstart the conversation by asking lots of questions:

- ‘What are your initial thoughts?’

- ‘How does this sit with you?’

- ‘What do you like about the proposal? What don't you like?’

- ‘What's your view on the value of an idea like this?’

- ‘What are your concerns?’

Then ask plenty of follow-up questions to keep the conversation going. Your aim is to gain as deep an understanding as possible of your audience's perspective so you know where they stand on your idea. This is going to help you to make any necessary adjustments at the next step in our sequence.

Embrace the ‘black hole’

It's highly likely in the second step that you'll start to see some pushback and resistance from your target audience. I call this the black hole. It's filled with the fears, reservations and concerns that are playing out in the minds of your audience as they think about your proposal. You can feel the black hole sapping the energy from a conversation, sucking any chance of a ‘yes’ into the ether.

Your first objective is not to ‘neutralise’ the black hole, but to understand it. The key is to acknowledge your audience's fears. To address the black hole, head on.

You might say something like, ‘I imagine there are all kinds of questions running through your mind about how this would work, and perhaps some concerns. I'd be really keen to hear what those are. I know if we don't address those now, then it will be difficult for you to get on board with this project.’

Keep asking questions until it seems they've run out of things to share (often the momentum builds as they get going, so for a short but scary time it may feel like a runaway train). Once you feel as though there are no questions left to ask and they've shared all there is to be shared, the best thing you can do is summarise the conversation to date and ask them whether there's anything you've missed. Use phrases like ‘Let me check I've understood everything you've raised so far …’ then confirm you're on the same page by asking whether there's anything you've missed.

The abrupt ‘no’

What happens if you're faced with an abrupt and explicit ‘no’ in the first or second step? You might feel like packing up your suitcase and going home (or throwing it out of the window), but it's too early to know for sure.

While ‘no’ can feel like an immediate shutdown, it's important to maintain a what's possible? attitude (which we explored in chapter 2). Assume for a moment that they have good reason for saying no, and that you've completely missed a beat. Adding the letter ‘t’ to their monosyllabic response can help you to imagine that ‘no’ is simply an incomplete version of:

- not today …

- not in that form, because …

- not unless …

- not until …

- not as long as …

In the face of an abrupt ‘no’, simply ignore and explore. In other words, ignore the presenting ‘no’ or counter-demand, and instead remain focused on understanding why they've said no. Steer a steady course and embrace that black hole!

Step 3: Adjust

The third step is to explore how you might adjust your proposal to address your target audience's concerns and unmet needs.

As tempting as it might seem, the aim here is not to resolve everything they've raised in one go. Nor is it to assume that you will be able to come up with a neat solution to everything in one fell swoop. To do this would be putting far too much pressure on yourself.

Besides, there is tremendous power in taking the time to allow your target audience to contribute ideas for addressing the objections or concerns they've raised. Don't assume that they even want you to come up with a tidy solution to all of their fears. Your attempts to solve things too quickly may deprive people of the very thing they need: an opportunity to work through their concerns, to have a voice in how your idea is implemented and to feel heard and understood.

If you put them into the seat of troubleshooter (rather than troublemaker) you allow them the chance to be the hero in this conversation. Let them be part of the exploration. If they do come up with a solution then it's more likely to make them a raving fan of your work — always a good thing when it comes to buy-in.

Here are some questions you might ask at this step:

- ‘You mentioned this would cause confusion in the marketplace. How do you think we can avoid that? I'd love to hear your ideas.’

- ‘The last thing either of us would want is to have our team working on the wrong things in the wrong order. Did you have any ideas about how we could overcome that?’

- ‘We established earlier that there may be a skills issue that would make it hard to get this project off the ground. Here's what I'd propose to mitigate that risk … Can you see that working?

- ‘I fully understand your concern … If we do go ahead with this, what would it need to look like to get around that concern?'

Step 4: Recommend

This step is where your audience begins to adopt a stance of ‘Okay, this could be something I might be willing to agree on …' They may say something along those lines to you, or they may give the air of someone who no longer has any major reservations or concerns. Either way, you're looking for signs that the black hole has receded into the distance.

The aim here is to table a clear version of your idea or initiative for their buy-in. In other words, this is where you finalise a proposal for people to say ‘yes’ to.

How about this …?

It's at this point that you need to pull together the threads that have emerged from the previous three steps, and drive the conversation towards a logical yes. There are two ways to do this:

- Make a recommendation yourself. Based on what you've learned, and the adjustments you've explored together with them in steps 2 and 3, you might now say something like: ‘So, based on what we've been discussing, here's what I'd like to suggest … ’

- Ask them to make a recommendation. This is a little more risky, as it's putting the ball in their court. But it can be an incredibly powerful moment if they play. You might say something like, ‘So let's see if we can pull this conversation together into a concrete next step. How would you recommend we go about this?’

Even though both of these are framed as questions, it's important to imbue this step with a little more forward momentum. Keep an eye on the energy levels of the conversation, and don't be afraid to unleash your catalyst and step into a bit more of a leadership role. For example: ‘How's this for a suggestion: why don't we run a pilot event next week and invite one person from each of the management groups, and then use that as an opportunity to refine our approach? Are you happy if we run with that?’

If they are still hesitating — or perhaps even showing outright resistance at this stage — you know you've probably tried to move things forward too fast, in which case you might need to rewind the tape back to step 2, Learn.

Hint at implementation

As you start to drive the conversation towards agreement (step 5), you might also begin to explore questions around implementation. Questions such as these:

- When would be the best time to start?

- How long do we need to secure budget for this?

- Who else needs to be involved?

- What's the best first step?

In fact, this aspect of buy-in corresponds with the third dimension of our 3M model, Movement, and is the focus of the next chapter. But touching lightly on this conversation as part of the Recommend stage is a great way to test the waters around your target audience's readiness to move into the final Agree stage.

More than anything, exploring implementation helps your target audience (and you) to make an important shift: a psychological shift from ‘this is just an idea’ to ‘this is something we're serious about doing’. This triggers a shift into very different thinking gears, and it can also evoke a different emotional response that either helps you to build positive momentum (‘I can't believe we're actually going to do this — how exciting!’), or it can highlight that you need to slow things down a little (‘Hang on, I just don't feel comfortable about this …’).

It's like standing at the open door of a plane at 10 000 feet, having made the initial decision to go skydiving while in the sheltered comfort of your home.

Step 5. Agree

After patiently guiding the conversation through the first four steps, you're now at the point of tying it all together — turning ideas and discussion into agreement and commitment. With a nod to the title of that classic book on negotiation, it's time to get to yes.

So are you in or are you out?

In the world of professional selling, they tell you to ask for the business — the part many people forget or skirt around. People awkwardly and fearfully bale midway through the conversation, simply because they're scared that after all this hard work they might not get a clear ‘yes’. To quote Peter Cook, co-author of the book Conviction: How Thought Leaders Influence Commercial Conversations, ‘If you have something of value, something that could change this person's life, that could make their world better, and you've both spent an hour with the express purpose of determining whether this is for them, and you want to work with them, ask for the business. Make the invitation. If you don't, you have wasted both your time and theirs … You've brought them to the brink, you've shown them a new possibility, a different future, and then you've yanked it away from them.’

In the context of buy-in, asking for the business equates to asking for their support. Now is the time to seek a ‘yes’.

You can do this by asking one of the following types of questions:

- ‘Can I have your support on the basis of what we've discussed here today?’

- ‘So are we all on board with the following proposal?’

- ‘Are you happy to proceed based on everything we've discussed here?’

- ‘Is that a “yes” from you?'

This is when the champion of buy-in surrenders to the merit of their proposal. At this point, it's all about the value and proof as your audience sees them. If you've done your work throughout the preceding four steps, then you'll have done everything you can to paint the right picture around both of those elements. Now let those things be the deciding factors. Don't confuse the moment as one in which they might accept or reject you. They are now making a fully informed decision about how they feel about the overall merit of the proposal, and unless you've rushed things, it's unlikely there's much more you can do to influence that view.

On the flipside, asking for a ‘yes’ prematurely is something to be wary of, because chances are you won't have done enough to ensure the best chance of success at this point.

Pick your moment

In chapter 5, we explored the importance of timing (remember, it's the secret of comedy and the key to catching a surfable wave).

The timing with which you ask your audience for their agreement is crucial. Rush it and you may get knocked back simply because they feel pressured. Allow them too much time and the moment may be lost.

So how do you know when to ask? Well, there's no simple answer to that question, but there are two things to consider. First, if the moment is brimming with signals that read, ‘I'm in, I'm in’, then seize that moment. To return to my surfing analogy from chapter 5, don't miss a good wave when it comes.

The second consideration is whether it is useful to ask them for clearance. You might say something like, ‘Well, given where we've got to today, I'd be very keen to know whether I have your support. How are you feeling at this point? Do you need any time to consider?’ If their answer to this is yes, then the next thing to do is lock down the time when you will reconvene. For example: ‘That's absolutely fine. How about I revisit this with you in a week's time?’

The underwhelming yes

On 13 December 2015 French foreign minister Laurent Fabius sat in front of an auditorium filled with hundreds of political dignitaries from around the world and declared, ‘I see the room, I see the reaction is positive, I hear no objection. The Paris climate accord is adopted.’ He then added, ‘It may be a small gavel but it can do big things.’3 And so Monsieur Fabius closed the global climate change conference in Paris, and world leaders forged an international accord to curb man-made greenhouse emissions. As the sound of the gavel echoed around the chamber, ministers stood up to cheer and applaud loudly. The deal was done.

But not every scenario will result in the kind of spontaneous applause and celebration unleashed by the French minister's gavel. Sometimes buy-in comes with a small or underwhelming yes. Perhaps they shrug their shoulders, nod slightly and say something like, ‘Ummm, okay, I guess so.’ And you're thinking to yourself, ‘Oh for goodness sake, is that the best you can give me? What's the problem now?’

The champion of buy-in knows when it's time to embrace the first yes — even if it's a guarded one — and treat it as an opportunity to get the wheels in motion and build some momentum. Think back to when your target audience stepped onto the path — right back at the Explain stage. What was their demeanour then? And how does their current state compare with that?

If you've managed the journey along the path to yes with empathy and sensitivity, then you will have given them plenty of space and opportunity to make the transition. You will have helped them to feel heard and done what you can to tailor your idea to account for their concerns.

You will have made it your priority to ensure your audience sees the value and proof in your proposal before asking them to buy in.

All of these things will have been instrumental in getting to this point: a logical yes. And, if the Mood is right, you now have a willing heart and a willing Mind. Wow … congratulations!

But don't be fooled into thinking that your work is done — that it all somehow stops here. Quite the reverse, this is where it all begins. After all, as Pablo Picasso once said, ‘Action is the foundational key to all success.’

***

So there you have it, the second dimension of our 3M model, Mind. We've been exploring what it takes to guide your target audience towards a logical yes, helping them to establish value and proof. We've seen how important it is to go slow to go fast, and to allow your audience plenty of opportunity to voice their concerns and to have a say in the final outcome.

Everything in this book so far has been a step along the journey of creating buy-in. With Mood and Mind in sync, perhaps your target audience is finally declaring, ‘Yes, I'll work with you. Deal!'

Now's the time to explore how to turn that ‘yes’ into action.