3

CONTROLLING ATTENTION

The first step in the program is waking up, which we illustrated in Chapter 2 with the exercise of listening to sounds happening in the here and now. You can plan by imagining what might happen in the future, informing your plans by drawing on past experience. This is an intentional process that we call reflection, and it keeps the present as the frame of reference. (In contrast, waking sleep is an unintentional drifting into thoughts about the past or the future.) The exercise was aimed at bringing you back into the present, but it did in fact include the second step of controlling attention: you were invited to focus your attention actively and intentionally on the sounds you could hear. The two steps happen together, but they can be described as a two-stage process: until you wake up, attention isn’t available to you. Attention hasn’t stopped, but it has been so effectively absorbed in the dream that you’re unaware of what’s happening in the present. Waking up was described in detail in Chapter 2. In this chapter we will expand on the second step of controlling attention.

Attention is like the beam from a flashlight. Your brain is the flashlight. If someone calls your name, you swing the beam of attention to focus on who is calling and why. The person might have called you to look at a plane flying overhead, and you open your attention up to the sky, searching for it. Once you spot it, you focus your attention on that one point in the sky. Attention varies along a continuum, from sharply focused on one point or wide open to stimuli, but all along the continuum you control and give it intentionally.

Nothing happens without attention. A report arrives on your desk, and instead of dealing with it, you drift off into plans about next weekend. Attention hasn’t stopped, but you’ve lost control of it. In waking sleep, all that attention creates is only dreams; the review of the report that you’re supposed to be doing has stopped. Waking up and attending to the report is focusing attention on it. You may be drawing on previous experience to do the review, but this is the controlled thinking process of reflection. During reflection your attention can become completely absorbed in the review, but this is all happening intentionally. If the task is proving difficult, you might sit back and stare out of the window for a while, and your attention may drift back toward your plans for the weekend—whom you’ll meet, what you’ll wear, what you’ll eat, and so on. There is no less attention involved, but you’ve allowed it to slip from your control and be drawn into waking sleep.

The waking-sleep thoughts about the weekend can be a welcome break from grappling with a difficult problem. It is also true that a solution will sometimes miraculously manifest in waking sleep, just as it might during dreaming sleep, but how many really useful solutions have come to you in these states of mind? One example was the discovery of the structure of benzene, which Friedrich Kekulé claimed occurred to him in dreams about a snake eating its tail, forming the ring structure that characterizes the benzene molecule. Such examples lead to an unwarranted notion that some of our best ideas come during waking sleep, but a closer examination will show that in fact, most creativity is 90 percent perspiration and 10 percent inspiration. Sweating it out happens in reflection, not waking sleep. Another mistaken idea about creativity is that it involves completely unique inspirations, but discovery means just that: discovering, taking the cover off what was already there. Creative people are able to see and make new connections between things or ideas that already exist.

Being aware of attention is really quite simple: as you’re reading this page, be aware that you’re paying attention to the text. Acknowledge that you can do anything in a mechanical, automated way, or you can be awake and aware of what you’re doing. This brings you out of waking sleep, and it is also what will bring you out of stress.

RUMINATION: TURNING DREAMS INTO NIGHTMARES

In Chapter 2 we extended our continuum of ordinary sleep to waking sleep. Although there are efficiency costs in being absent in daydreams, there is no stress involved. The real costs begin when negative emotion is added, transforming the daydream of waking sleep into the nightmare of rumination. Defining stress as rumination provides a new way of thinking about stress, and it offers a simple method to avoid becoming stressed altogether.

Paradigm shifts occur when a new way of thinking replaces a previously held convention. In science, this doesn’t mean that the original paradigm is rejected entirely. Einstein’s relativistic physics didn’t reject all of Newton’s laws. Science is a cumulative process, in which a pathway to understanding is established and followed until the path takes a turn to include new information, which in contemporary science is often brought about by more advanced instruments. The turns can be very sharp, but paradigm shifts are seldom catastrophic. They can take time, especially if the new ideas are strongly resisted. People continued to believe that the earth was flat and that it was the center of the universe for a long time after those views were shown to be false. So, too, with the ideas about stress that have become so ingrained in popular thinking. For the past three decades we’ve been arguing that a shift in the stress paradigm is long overdue and that the conventional methods of stress management couldn’t possibly have any real benefit. In this chapter we want to discuss the central, most important part of our approach, which is to define stress as nothing more or less than ruminating about emotional upset.

The flat-earth view of stress is that it is caused by events and that it can in some way be good for you. Our view is that events simply offer something for you to ruminate about, but whether or not you do so is a choice that you can make. To understand this, we made an important distinction in Chapter 1 between pressure and stress. The conventional approach is to distinguish between supposedly good and bad stress, but in this chapter we want to show you that there is nothing useful about stress at all. Pressure, on the other hand, may be very useful, acting to motivate and spur us on, but pressure is just a demand to perform. Pressure varies, from the simple demand to get up when our alarm goes off to having to deliver work by tight deadlines. The pressure might be intense, but there is no stress inherent in it until rumination is added.

For example, at the end of a team meeting while everyone’s packing up, your manager tells you across the table that you need to get a grip or soon there won’t be a place for you in the organization. What happens next isn’t an idle reverie about the weekend, but thoughts filled with intense emotions: anger at your manager for telling you off publicly, embarrassment in front of your colleagues, fear of losing your job. Dwelling on these emotions is rumination, but let’s place it in context. What your manager is doing is telling you that you need to improve your game. He or she may have acted inappropriately in not discussing this with you privately, but that could happen for all sorts of reasons, including your manager’s being in a state of rumination about the team’s performance. If you leave out all the imagined negative scenarios, the demand to work harder is just pressure, a demand to perform better. There is no emotion inherent in it, even if your manager has told you this in an inappropriate way. The anger you feel is what you’ve added to it.

We’re human, so when things like this happen, we will inevitably feel the emotional effects. That’s natural, but what isn’t natural is elaborating them into rumination. The cost is twofold: emotional and physiological. We’re all familiar with the emotional aspect, and it’s no fun feeling angry or embarrassed, but these feelings will pass, and the sooner, the better! They serve no purpose other than to remind you that something needs to change, and that can be done in a reflective rather than a ruminative way. As we said in Chapter 1, worry is completely pointless. Yes, be concerned that you need to do something, which might even mean brushing up your résumé, but all that ruminating about it will only prolong the misery.

So what happens to us when we ruminate? Here’s a practical example. Your company is planning a restructuring, and you’ve been asked by your manager to look at the makeup of your team and provide feedback on how the team might be reorganized to fit within the proposed new structure. Coming to grips with the restructuring issue may involve walking down the hall to talk to a colleague about it. You might intentionally think about the past to remember what you did the last time and whether or not it worked, as well as about the future to consider how other approaches might work. All of this is an intentional, controlled use of attention. Once the issue has been appraised, attention is then focused on the strategies to address it. When attention is given to a problem, solving it begins to progress, with new information to be processed and assimilated. In practice it is unlikely to be so clear-cut, but in principle this is a model of how work gets done. The process followed here is what we’ve described as reflection. In this scenario, it would be a case of the manager describing the proposed restructuring and the anticipated outcomes, and then you getting on with it.

Let’s discuss a second scenario. This time you think, “Not all that again! We’ve just been through a restructuring that made absolutely no difference at all!” Your attention drifts away to something that seems more interesting, like the dinner you’ll have with friends after work or the trip you’re planning for next month. There’s still attention, but now it’s distracted by a daydream about pleasanter things—in other words, waking sleep. Since you can’t work and sleep at the same time, the job you’ve been asked to do comes to a standstill, and it will remain that way until you wake up and return to the present. There is a performance cost but no stress. To bring stress into the picture, we need to add an ingredient: negative emotion.

Here’s a third scenario. This time your manager gives a blunt overview of the issue, and on the way out he turns back and says, “Just do a better job of it this time, not like the last restructuring you messed up!” What follows is no idle fantasy about next weekend, but anger, fear, resentment, and thoughts of revenge. It’s not a happy place to be.

FIGHT OR FLIGHT AND STRESS

To understand the biochemistry of stress we need to take into account three key components, the first of which is a segment of brain tissue at the base of the brain called the hypothalamus. This is connected by a short stalk to the second component, the pituitary gland. These two are connected in turn to the third component, the adrenal glands, of which there are two, one on top of each kidney in the small of your back (each adrenal gland has an outer part called the cortex and an inner part called the medulla). The three components act in concert, and the system is referred to collectively as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which we can fortunately abbreviate to HPA.

A way to illustrate the connection between the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal glands is to remember the last time you were suddenly startled—for example, perhaps you were engrossed in something in a quiet room, and a gust of wind suddenly slammed the door shut just behind you. If you had checked your body at that time, your heart would have been racing, and your hair might have been standing on end. This we’ve described earlier as the fight-or-flight response. Fight or flight doesn’t just happen. It is a decision: we respond differently to different situations. We ordinarily think about decisions as rather long-winded processes of mulling over the options, but decisions can happen without all of the cogitating when they need to be made very quickly. When you perceive that whatever has happened might be a threat, your hypothalamus is stimulated, and that in turn stimulates the medulla of your adrenal gland. This is a direct neural connection, and it is consequently extremely rapid. What the adrenal medulla secretes is adrenaline, and adrenaline prepares you for action, increasing your heart rate and blood pressure to maximize oxygen for your muscles so that you can fight or flee.

This is not stress. Adrenaline is sometimes called a stress hormone, but it is in fact simply a hormone doing exactly what it is designed to do: prepare you for action. There is always adrenaline in your system, and it is produced elsewhere in your body, but the medulla is specialized to release a large quantity very rapidly. Adrenaline regulates arousal, and the response varies according to demand (remember, it is a decision). You might remember drifting off a bit during a talk or a meeting, and then someone said something that really interested you. Ping! You suddenly became alert, facilitated by an increase in adrenaline, albeit a much smaller response than the crash of a door slamming unexpectedly behind you.

With a full-blown fight-or-flight response, adrenaline levels rise dramatically, so much so that you can really feel the effects of an adrenaline rush, though you can’t become addicted to it. So-called adrenaline addiction is simply a desire for stimulation regulated by the same physiological process. Fight or flight is also accompanied by an increase in the secretion of endorphins—that is, naturally produced morphinelike hormones that help to reduce the perception of pain. Endorphins are probably responsible for soldiers being unaware of wounds they’ve sustained. The link to morphine led to muddled notions about athletes who push themselves to their limits being addicted to endorphins. There is no such thing.

In some respects fight or flight doesn’t entirely capture the way that people respond to intense demand. We’ve also described freezing, when the emotion catches you and leaves you literally frozen by fear. Fight or flight describes an entirely appropriate response. Although some animals freeze to merge into the background and escape by becoming invisible to predators, freezing or panicking are likely to lead to disastrous outcomes. We saw that with our white-water rafting metaphor in Chapter 1, and with Derek’s actual experiences during a major earthquake. The complex emotional responses we make are mediated by the interactions with other parts of the brain, but whether you react by fighting, fleeing, freezing, or panicking, all of it is associated with a dramatic rise in adrenaline.

The increased physiological arousal provoked by adrenaline is not stress per se, but there is a significant potential cost involved. Imagine a river with a bend in it. The flow of water will cause an increase in the pressure against the outer bank of the river as it turns the bend. When the river floods during a storm, the pressure increases to the point where that outer bank begins to erode and collapse. Now substitute for the river your coronary artery, which emerges from the top of your heart and loops back down to feed the heart muscle itself, with many bends and forks. The increase in adrenaline is equivalent to the flood. The rise in blood pressure and heart rate means an increase in cardiovascular strain, and like the outer bank there may be damage to a fine layer of cells that lines the inside wall of the artery. The purpose of this layer is to help inhibit the accumulation of blood-borne fat sticking to the wall of the artery, which can happen if there is a lesion or damage to the cell layer. The fatty plaque that forms can harden and eventually block the artery, resulting in a form of heart disease called atherosclerosis. Sustained high levels of adrenaline are linked to chronic high blood pressure.

How does all this relate to stress? Think about the last time someone said or did something that really annoyed or offended you: how often and for how long did you go on thinking about it afterward? Every time you did, you provoked fight or flight. It may not be as intense as when the event happened, but it increases and is sustained for as long as you are thinking about it. This is ruminating about emotional upset. Most of us know that cows are ruminants: they bring up the cud, chew for a while, swallow it, and then repeat the process. At least this is useful, gradually breaking down the cellulose in the grass so that it can be digested. Churning over emotional upset serves no purpose at all, except to make you miserable and potentially to shorten your life.

People sometimes say that it’s human nature to ruminate. That suggests that it is natural, but doing something that makes you miserable and might shorten your life couldn’t possibly be natural. Nature is a self-regulating system devoted to preserving the species, so what’s natural is not ruminating. Rumination is also defended with the claim that you learn from doing it, but all that you’re learning is how to self-inflict misery. Thinking that you learn from rumination is confusing rumination with reflection. The distinction between them can’t be overemphasized. Reflection is problem solving (thinking through things without becoming involved in emotional upset), and it requires taking the third step in the program, becoming detached. Ruminating is churning over an imagined sequence of what-ifs and if-onlys repeatedly, and it solves nothing. To paraphrase Mark Twain, some of the worst things in your life never happened.

Defining stress in this way allows us to remove it from the event and to focus not on the triggers but on what is triggered: a cognitive-emotional response, interpreting what has happened and responding emotionally to it, coupled with the physiological changes that facilitate action. As we’ve said, this isn’t stress, provided that we can return to a resting level as quickly as is practicable. If rumination is triggered, the reaction is extended beyond what is useful. Resilient people don’t ruminate, which is why they’re able to adapt so effectively. Think about it as equivalent to a motor that’s run flat out continuously, compared with a motor that’s run on full only when it’s needed. Our bodies are designed to do the latter. Rumination overrides this natural tendency toward homeostasis, which is returning quickly to rest and recuperating from any wear and tear of the cardiovascular system.

Hormones such as adrenaline serve to translate perceptions into actions, and the process is entirely appropriate if the demand is not perpetuated by rumination. Another hormone that has a known effect is cortisol, which, like adrenaline, is erroneously described as a stress hormone. Cortisol is secreted by the outer part of your adrenal gland, the cortex, but the response is slower because where adrenaline is provoked by an extremely rapid nerve signal, the trigger for cortisol is hormonal and acts via the bloodstream. Cortisol also involves the HPA axis, but we need to add a further detail: the hypothalamus has a front (anterior) and a rear (posterior) segment, and it is the posterior segment that directly stimulates the adrenal medulla to secrete adrenaline. The anterior hypothalamus secretes a hormonal stimulant, called a releasing factor, into a duct that is connected to the pituitary gland. The releasing factor stimulates the pituitary to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) into the blood stream. ACTH is attracted to the outer part of the adrenal gland, the cortex.

When ACTH reaches the cortex, it provokes it to secrete cortisol. Cortisol has a range of functions, one of which is that it acts as an anti-inflammatory (the synthetic drug cortisone is based on the cortisol molecule). Inflammation is an entirely appropriate tissue-based response that occurs at the site of any injury sustained in fight or flight, but runaway inflammation can inhibit blood circulation to the affected area and retard healing. Another function of cortisol is to regulate energy levels by facilitating the release of stored sugar (glycogen), which provides the energy to fight or flee. It also conserves energy to deal with the immediate demand, and it does so in part by temporarily suspending high-energy processes such as producing certain types of white blood cells. There are several different specialized white blood cells, but cortisol has been shown to reduce both natural killer (NK) cells and to compromise T cells. NK cells are the frontline defense, acting quickly against a range of pathogens, while T cells regulate the overall immune response.

Continuing to churn over emotional upset maintains elevated levels of both adrenaline and cortisol. This helps clarify the difference between acute and chronic stress that we described in Chapter 1. Most of the negative effects of stress come from chronic rather than acute stress. When there’s an intense demand, such as having to complete a job by a deadline, you’ll feel the pressure, and your blood pressure and heart rate will rise as adrenaline levels increase to meet the demand. There are very few people who are under constant pressure like this, 24/7, so there are always opportunities for the emotional effects to recede so your body can recuperate. What makes the pressure constant is continuing to ruminate about the emotional upset in the absence of anything actually happening. Rumination is chronic stress. Acute stress isn’t stress at all, just pressure. The physiological effects we’ve described are well established, which is why stress can never be good for you.

STRESS AND EMOTION

Fight or flight is not just a physiological response. What triggers and sustains it is emotion. Although we’ve defined stress in terms of emotional upset, there’s nothing wrong with emotion. Emotion is part of what makes us human, and almost everything we do involves emotion. For example, different aspects of your job can be ranged along an emotional continuum, from “I hate doing this” to “I love doing that.” If you have an inbox, the bottom will be filled with “I hates.” Unfortunately, they don’t just disappear, and you find your attention repeatedly being distracted by remembering that they’re still there. One day you decide to do only them, and you then wonder what the fuss was all about! The fuss was put there by your not wanting to do the jobs and preferring to do something else, which was an emotional prioritization rather than a rational one.

Instead of prioritizing according to what’s most important, try doing the reverse: begin by deciding what isn’t important and needs to be trashed. Managers often impose on their reports the completely unrealistic expectation that they should do everything they are sent. When did you last get everything done? I recall a training session in which a manager turned to his team halfway through and said he didn’t expect them to do everything he gave them. A refreshingly enlightened view, though he did include an important rider: that the important things needed to be done 100 percent. If the team tried to do everything, they’d be lucky to deliver 70 percent, so prioritizing needs to be a continuous process that begins with identifying what isn’t important.

To make this decision requires keeping in perspective the emotion that clouds our judgment and turns prioritizing into preferring, but there may be a real problem in deciding what to focus on. Your manager has given you three tasks to attend to, but you realistically have time to complete only two of them satisfactorily. Which are the most important? The way out of that dilemma is consultation—that is, asking your manager directly. If she is a leader, she will be able to see that her expectation wasn’t realistic, and she will make recommendations: “Focus on these two, and if the third doesn’t get done, we’ll make another plan.” A mere manager (rather than a leader) will simply tell you to make sure you deliver everything. Changing jobs in tough economic times is neither simple nor easy, but it may be time to brush up the résumé—managers who disregard the constraints of time and money and make unrealistic demands are not worth reporting to.

In fact, with fewer workers doing more, the inevitable consequence is that everyone has too much to do. You can learn to manage the time available more effectively, but there is no training program that can create more of it. The conventional wisdom is that you need to work smarter, but no one tells you how to do it—don’t you just end up pedaling faster? It is possible to work a lot smarter, but the key to doing so is to be more awake.

Although emotion is an inevitable part of how we respond, it does need to be kept in perspective. The danger with emotion is not that it occurs but rather that there is potential for you to become involved and overwhelmed by it. The key to resilience is to avoid turning pressure into stress by needlessly adding in negative emotion and feeding it with attention. People sometimes say that without stress, they wouldn’t be sufficiently motivated, but what should motivate us is passion for the work, not stress. Stressed people work less well; all that the myth about stress being good for you has done is to provide bad managers with a justification for making impossible demands.

Emotions won’t stop when you become more resilient, but what does become available is a choice about how you continue to respond. The most important choice is not to ruminate about the emotional upsets, but there is another choice included in our model, which is whether or not you express your emotions. Derek’s research program was aimed at identifying the personal factors that made people more vulnerable to stress, and in addition to the key measure of rumination was a scale for emotional inhibition. These two measures formed part of what was called the Emotion Control Questionnaire (ECQ), and studies using the scales showed both that stress is rumination and that its effects can be mitigated by expressing rather than inhibiting emotion.

Rumination was unique to the research program, and the ECQ represented the first published index of rumination, but it wasn’t a great surprise to find emotional inhibition emerging as a factor as well. The benefits of saying how you feel is expressed in common aphorisms such as “A problem shared is a problem halved,” and much of the research at the time had shown the importance of this aspect of emotional response style. Getting things off your chest is the feeling of pressure being released.

The reasons people bottle up or inhibit emotion are many and varied, but central to it is the idea that expressing emotion is a sign of weakness, and doing so will make you vulnerable. In fact, the opposite is true. In the same way as not ruminating, expressing how you feel is a sign of emotional intelligence. It was also not too surprising to find a significant gender bias, with women far more willing to share their emotions. There can be little doubt about the greater emotional intelligence of women, who know and understand their emotions; for many men, how they feel is an embarrassment best kept secret. We do need to be clear, though, that we’re talking about the appropriate expression of emotion. We’re not advocating indiscriminate disclosure! People who are always venting have often just developed the habit of doing so. They’re not getting any resolution, and there are no benefits in it for them or the people who have to listen to it all the time.

The appropriate expression of emotion means not becoming identified with the issues all over again but, rather, talking about them in a way that leads to putting them in perspective. It is equally important that the listener maintain perspective and avoid becoming identified with the discloser’s issues. This is what empathy is. Becoming identified with others’ issues leads to sympathy, and nobody is helped by sympathy—you just have two people with the problem instead of one. Empathy is a cornerstone of effective leadership.

TAKING THE FIRST STEPS

When it comes to waking up, unfortunately, there is no magic bullet. The training program is not the road to Damascus, and like any useful behavior, it requires repeated practice if it is to become a habitual response. The first step of waking up can become habitual surprisingly quickly. In our training program, the sessions are sometimes split into two periods, with time in between for reflection and practice. The gap need only be overnight, and the homework is to ask participants to notice how much time they spend in waking sleep. On their return for the second period, everyone has become aware of periods of waking sleep. It isn’t that waking sleep has suddenly started or has increased but, rather, that people have become aware that it is happening. It is also typical that some return to the second period extremely concerned to have discovered just how much time they spend in a dreamworld, but they can easily be reassured by asking them how they knew they were in waking sleep. The answer has to be because they’d already woken up—knowing about waking sleep is always retrospective. Waking sleep is, after all, another level of sleep, and just as you wake up from a nightmare and realize it was only a dream, you know you were in waking sleep only after you’ve already woken up.

Having woken up, attention then becomes available to be used and directed intentionally to the tasks at hand. People sometimes say that what makes them feel stressed is not being in control, but they’re often talking about things that they have no control over anyway. The one thing you always have control over in principle is your attention, and that’s what really needs to be controlled. Something else many commonly say is that they do wake up, but it is all too easy to slip back into waking sleep. This is exactly what people find when they start to practice. Remember, nobody is awake all the time. The aim is to be more awake more of the time. A useful motivation to being more awake is to recognize the efficiency costs of waking sleep.

Realizing the significant health costs of rumination can certainly help to focus the mind, but it also helps to remember that rumination is a habit that can be changed. Our case studies have provided direct evidence for that. For example, in a large New Zealand company, we included staff from two sectors of the organization that were located in separate buildings. Challenge of Change Resilience Training had been planned for groups from both sectors, but while the groups from one sector received the training, it had to be postponed for the other sector. This provided the opportunity to compare experimental (trained) and control (untrained) sets of groups. In preparation for the training, participants from both sectors had completed the Challenge of Change Resilience Profile, which includes a measure of rumination (the profile comprises eight different dimensions, which we’ll be describing in detail in Chapter 5). One of the shortcomings of readministering tests is that participants’ responses are biased by recall, which was minimized by using a 13-month interval between testing.

The readministration of the profile showed a significant decrease in rumination scores for the trained group, while scores for the untrained group were unchanged. Because of continuing work with the company, it was possible to interview participants at the second administration of the tests to determine how much they had practiced the principles they had learned in the training program. The measure was an informal one, but nonetheless the trends indicated clearly that change had occurred mainly among those who had continued to practice the principles of the training. This is hardly surprising—training offers little benefit unless it is subsequently put into practice, but it was helpful to be able to confirm the effect.

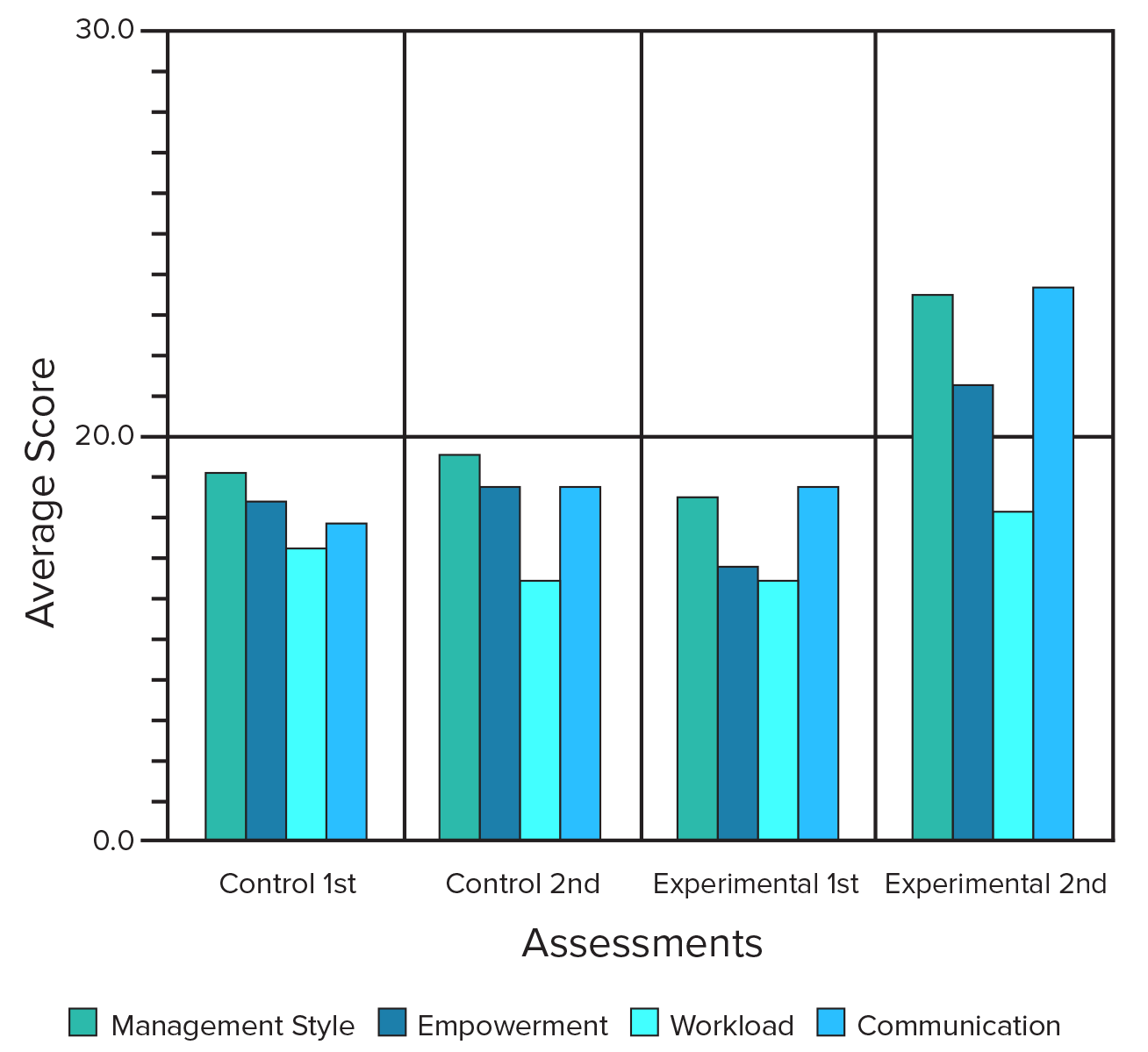

Further evidence for change as a result of the training came from analyzing the results of a climate survey that Derek developed as part of his work. The Challenge of Change Resilience Training Climate Survey was constructed using the same rigorous psychometric procedures that the profile scales were based on, generating items by asking respondents from a wide variety of employment sectors and levels to reflect on their experience of work, current and previous, and to say which positive features made organizations great to work for and which made them negative workplaces. The preliminary questionnaire based on their responses was given to a large sample of working people, again from a wide range of sectors and levels (gender was balanced), who were asked to rate their current organization on each item using the 4-point scale. Their responses were subjected to exploratory analysis to decide a final form of the scale, which was endorsed by subsequent confirmatory analyses.

The analysis yielded four workplace factors or components that are labeled Management Style, Empowerment, Workload, and Communication. The labels for the factors are to some extent self-explanatory. The first dimension reflects general perceptions of the overall management style in the company, the second the degree to which people feel they are able to act independently, the third the perception of how heavy the individual workload is, and the fourth the perception of how open and effective the communication of information is in the company.

Using the statistical weights for each item, the four dimensions were regularized to comprise 10 questions each, which means that scores range from zero to 30; scores in the range from 20 to 30 represent positive perceptions of organizational climate. Of the four dimensions, average scores for Workload tend to be lower than the other three, reflecting the relatively increasing workload that has generally been experienced in most economies in recent decades. The four dimensions do correlate fairly strongly and can be pooled to provide an overall measure of organizational climate, but using them independently offers a more targeted and detailed picture of employees’ perceptions.

The readministration of the climate survey in the second case study provided before- and after-training scores for the groups that received the training, as well as first and second administration scores for the untrained groups over the same period. The results showed a significant increase or improvement in scores for the trained groups on three of the dimensions (Management Style, Empowerment, and Communication), as shown in the graph in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1

The lack of significant change in the Workload factor of the scale was not surprising. Workload is in fact a measure of pressure or demand, and neither this training nor any other will reduce pressure. Together with the findings for the rumination dimension, what the results revealed was the same degree of pressure but a less stressed (in other words, less ruminative) way of responding to the pressure among those who had received the training.

STRESSLESS LEADERSHIP

There is no question that leaders in the twenty-first-century workplace are under increasing pressure. Each year we work with over a thousand leaders in our training programs whose workplaces are characterized by BOCA conditions:

- Blurred boundaries where new technologies mean that work has penetrated all times and locations

- Overload from the volume of work exceeding the ability to keep pace with it

- Complexity of problems becoming more systemic and difficult to solve

- Addictive, meaning that many leaders with high-achieving personalities are addicted to the stimulation of work

And that’s just at work. Much of what people describe as workplace stress is actually stress they carry from their personal lives: ruminative thinking isn’t something you leave at the door to your office. The opposite is equally true: rumination won’t necessarily stop when you walk through your front door. Minds are portable, and we carry our thoughts with us wherever we go. What might change is the theme of the rumination: when we ask participants in our workshops to list their pressures at work and at home, the top three for the former are workload, change, and deadlines, and for the latter, family, health, and finances.

With all these pressures, is it possible to lead yourself and your team and be happy at work and at home, without getting completely stressed out? The answer, as proven by many of the leaders we work with, is a definite yes. We describe those who don’t get stressed—in other words, who don’t ruminate—as being resilient, but we’ve also emphasized that rumination is a habit. It may be a well-practiced one, but habits can be changed, so resilience is a skill that can be acquired by training. It all begins with waking up, and leaders who often drift off into waking sleep are constantly saying how stressed they are. They lack resilience skills. Comparing their habitual behavior with the skills of resilient and effective leaders, the contrast looks like this:

Skilled in Resilience

- Understand the difference between pressure (external demand) and stress (rumination), and teach their people to do the same

- Accept that pressure is a natural part of having a job, whereas stress is chosen

- Focus on what they and their team can control or have influence over, especially their attention

Unskilled in Resilience

- Constantly think about the what-ifs and if-onlys, without realizing they’re ruminating

- Imagine events to be bigger and more consequential than they really are

- Ruminate about other people and what others might think of them

We’ve said many times that resilience is a learnable skill, so here are four practical steps leaders can take to enhance their resilience.

1. Help your team differentiate between pressure and stress. Most people think these two are one and the same. They are not. Don’t you know some people who face very little pressure in their lives but are very stressed? Don’t you also know some people who face a great deal of pressure and yet are not stressed at all? In our workshops we often ask, “Does everyone in this room face pressure?” Everyone nods in agreement. Then we ask, “Is everyone in this room stressed?” There’s usually a silence before someone says, “Yes, of course we’re all stressed,” but others then speak up: “No, I’m not stressed.” When scores from the profile are discussed in the group, the leaders realize that everyone in the room is facing roughly the same pressure but that the stress levels vary widely.

While it is not a universal rule, we often see in our work that the higher people go in the organization, the less stressed they are. You might argue that this is because people at the top have it easier. That could be true, but we doubt it. Looked at more closely, the truth is that those who keep getting promoted are most often the ones who can handle more and more pressure without turning it into stress.

2. When you wake up from ruminating, ask the question, “How useful was that?” When I (Nick) first learned about Challenge of Change Resilience Training, I was going through a high-pressure health challenge, and I realized I was ruminating constantly. One exercise that helped enormously was to ask myself, “How useful were the last 12 minutes of rumination?” It was a genuine question because I felt that perhaps some real value had been created by doing it. I discovered that no matter how many times I asked, there was never an occasion when anything useful came of it. This contradicts the belief that many ruminators have, that rumination needs to be maintained because it has some useful purpose. Once you start to see that your ruminations serve no purpose, the grip that these pointless, negative thoughts have over you starts to release.

3. Scratch the rumination record. Many still remember what it was like to play records on a turntable. A new record would play perfectly, but as it got older and scratched, the needle would start to jump out of the grooves. If you scratched the record enough, pretty soon you couldn’t play those familiar tunes at all.

Rumination is like a record. We have favorites that we play over and over in our head without any helpful outcome (“Does my boss hate me?” “What if there are layoffs?”). What we need to do is scratch the record as soon as it starts playing. We do this by interrupting our thoughts as quickly and powerfully as we can. Once you’ve taken the vital first step of waking up, one of the most powerful ways to maintain this state is to physically move: stand up and go for a brisk five-minute walk. Don’t fall into the trap of spending the entire walk continuing with the rumination. Connect with the present for as much of it as you can. The way to do that is to remain connected to your senses. When you move with intention, you get out of your mind and back into your body and the world around you.

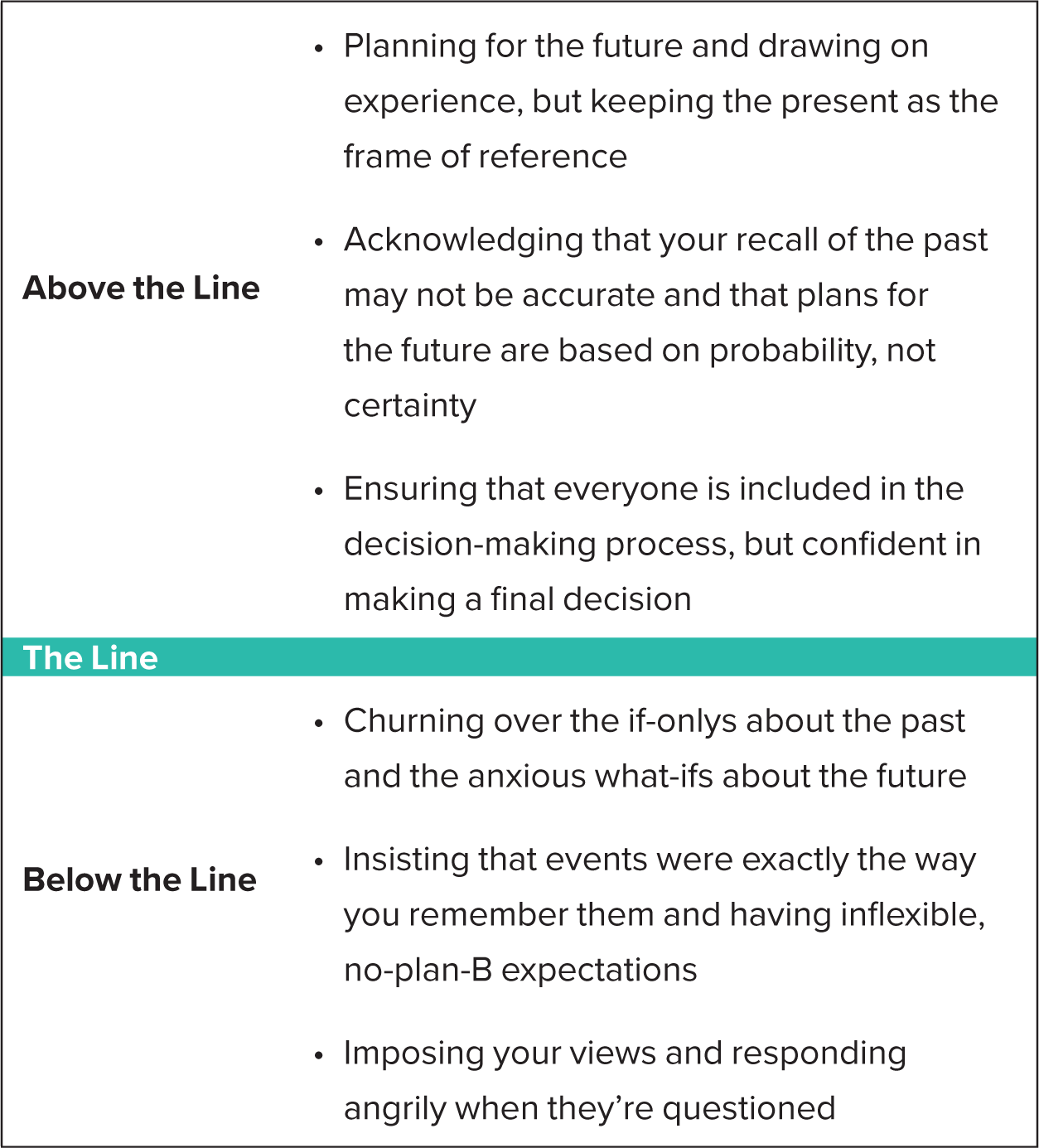

4. Turn rumination into reflection. Some leaders are confused by the distinction between rumination and reflection. Both involve thinking, but they couldn’t be more different. Figure 3.2 shows a good way to illustrate the difference by using a simple visual representation that has a threshold shown by a horizontal line.

Figure 3.2

When you think about the past or the future in a positive or even a neutral way, this is reflection, and we call this above-the-line thinking. Rumination is below-the-line thinking. Reflection is essential for good leadership, while rumination is disastrous. When you catch yourself thinking about something, stop and ask yourself, “Am I reflecting in a positive or neutral way, or am I ruminating and making myself stressed?” The former helps you create direction, alignment, and commitment for your team. The latter will lead to a short, miserable life. Choose wisely!

CASES IN POINT

Power Plants

We once worked with a group that included electrical power plant managers. During the first session one of the leaders asked if we were actually telling a group of power plant operators that they should never think about what could go wrong! The answer of course was no, we were not saying that. What we were saying was, think about it, plan for it, be ready for it—just don’t fall below the line and ruminate about it.

The rest of the group then shared that, in fact, the worst person to run a power plant would be a chronic ruminator, who would make everyone anxious. In their view, the best managers were those who could look at the plant and their work in a detached way, which allowed them to do two things:

- Plan for what could go wrong and how to respond, without ruminating about it (future focus)

- Reflect on past mistakes so that they could learn from them (past focus)

Football Teams

We saw the same principle in action with a professional football team. On the Monday morning after each game, the players would gather in the film room, and the coach would play a video of key parts of the game. He would constantly stop the video to point out what they did well on a particular play and where they had made mistakes (learn from the past). Once they had watched the whole game, the coaches would then switch the players’ focus toward the next game and what they needed to do to prepare (plan for the future). For the rest of the week the players practiced implementing that plan to the highest quality possible (focus on the present). The players and coaches didn’t ruminate about the last game or the next one. They stayed above the line and used all three time dimensions—past, present, and future—to get the job done as well as they could.

SUMMARY

- Stress is rumination, which turns pressure into chronic worry and sustains fight or flight when there’s nothing to fight or flee from.

- Resilient people don’t ruminate.

- Resilience isn’t a matter of being able to surface more quickly when you’re submerged by the flood of feeling that you have too much to do. Resilient people know there’s no flood to survive—just pressure that comes and goes.

- Waking sleep has efficiency costs, but the real costs come with the addition of ruminating about negative emotion. To escape from these dreams and nightmares, we need to wake up.

- The habit of going into the dreamworld is countered by staying awake for as long as you can whenever you do wake up. Nobody is awake all the time, so waking sleep will always occur, but rumination—and therefore stress—can be avoided altogether.

- Once you’re awake, attention becomes available for you to use intentionally. There is attention in waking sleep and rumination, but it’s been hijacked by your thoughts.

- Expressing emotion is helpful in mitigating the effects of rumination, but it needs to be expressed appropriately.

- As a wakeful leader, you can help your teams do the following:

- Differentiate between pressure and stress.

- Upon waking from rumination, ask, “How helpful was that?”

- Scratch the rumination record.

- Turn rumination into reflection (practice above-the-line thinking).