2

WAKING UP

In an average 24-hour period, how much time do you spend asleep? The answer is likely to be around 8 hours, but let’s look more closely. What do you mean by “asleep”? This might sound like an obvious question, to which you’ll probably answer, “Eyes closed, not aware of anything, deep and regular breathing.” And what do you mean by “awake”? This also seems obvious, and the answer would probably be along the lines of, “Open my eyes, get up and dress for work, and stay that way until I go to sleep again that night.” What this suggests is that there are two states of consciousness, awake and asleep.

We’re not going to digress into philosophical arguments about what consciousness is, but our everyday model of a simple dichotomy between awake and asleep is oversimplified. In fact, what we hope to show you in this chapter is that people are asleep most of the time, which is why the first step in this program is waking up! The real problem, as we’ll see in Chapter 3, is not just being asleep but the addition of negative emotion to the mix. Ruminating about emotional upset is what we define as stress, and avoiding rumination is the fundamental key to developing resilience. First, though, a brief overview of what we ordinarily think of as sleep.

TO SLEEP, PERCHANCE TO DREAM

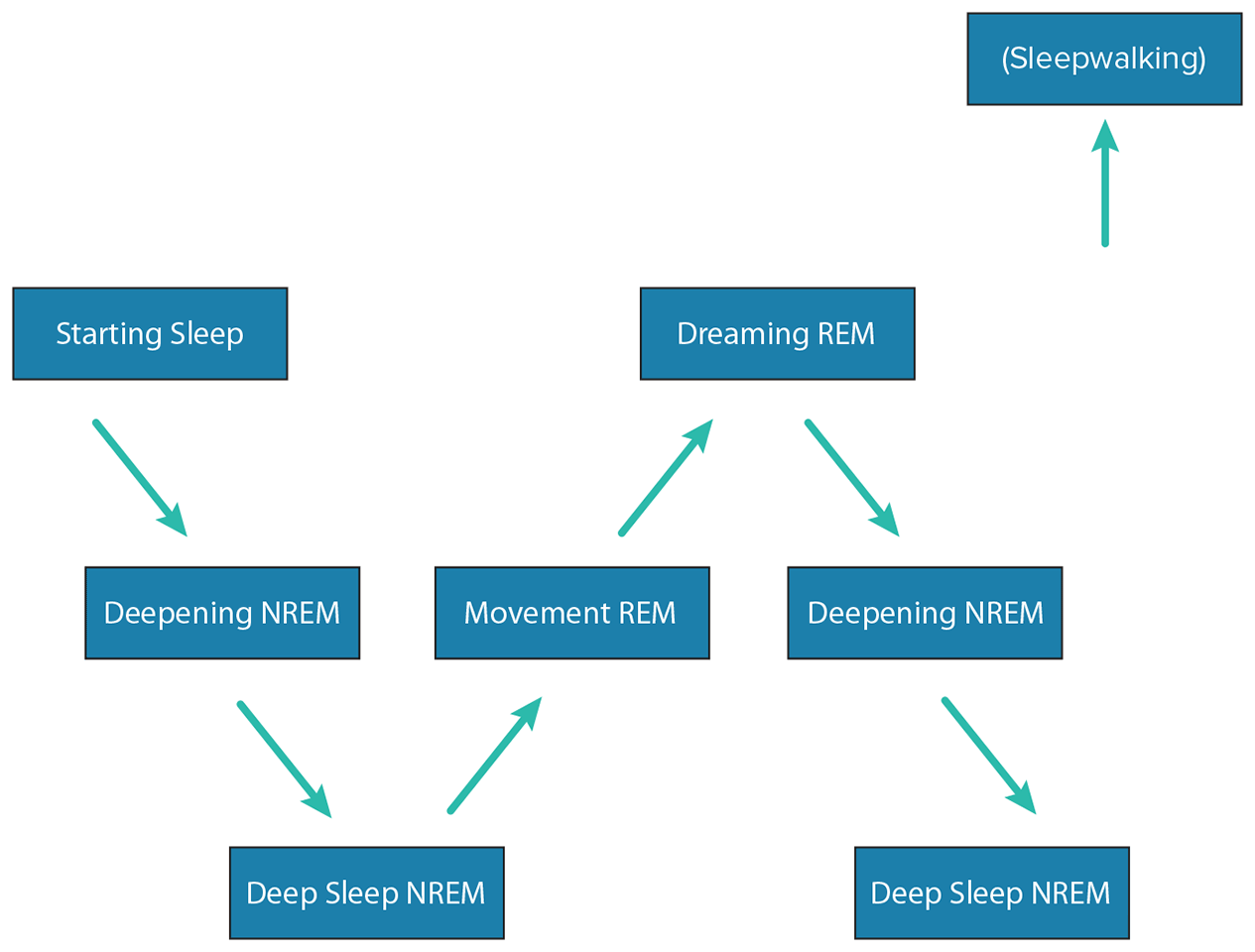

Researchers draw a broad distinction between sleep that is accompanied by rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-REM (NREM) sleep. What happens when you drift into sleep at night is that you quite quickly move into NREM sleep, which over the next 25 minutes or so descends into a particular state called deep sleep. Lasting for about the next 30 minutes, your body becomes completely relaxed, and apart from essential movements such as breathing, you become very still. You’re unaware of anything going on around you, you are difficult to wake up from this state, and if you are woken up, you probably feel a bit disoriented until you’re fully awake.

This state of deep sleep is what we would correctly call “sleep,” but during the course of the night you don’t stay there. At the end of the first stage of NREM deep sleep, REM sleep begins. This is when you start dreaming, and you may move about. During this dreaming sleep, which lasts for about half an hour, you’re easier to wake up than from deep sleep. You’re not directly aware of what’s happening around you or responding to it, although sounds can become incorporated into your dreams. In addition to eye movement changes, the switch between these two states of deep sleep and dreaming sleep has other characteristics that can be measured, such as brain activity. The easiest way to measure brain activity is to use an electroencephalogram (EEG), attaching electrodes to particular sites on your scalp and tracking changes in the electrical wave forms. These wave forms alter in direct response to the changing levels of sleep, with the pattern for dreaming sleep resembling that of normal waking much more than that of deep sleeping.

Do you sleepwalk, or do you know someone who does? If so, you know (or would have been told) that sleepwalkers may get up, dress for work, and even prepare food. Interestingly, it originates in NREM sleep, and it isn’t necessarily an acting out of dreams. When we dream, our limbs are semiparalyzed by a brain mechanism that prevents us from acting on the dreams. In part, it seems that sleepwalkers override this mechanism, and they engage in surprisingly complicated actions. Perhaps because the brain mechanism hasn’t fully matured, sleepwalking is more common in children than in adults. Because sleepwalkers engage in activities while asleep (there are claims that people have driven long distances while in a sleepwalking state), it can become a problem. It is generally regarded as a sleep disorder, and it affects as many as 1 in 10 adults.

Sleep is a complex process that isn’t fully understood, and since this isn’t a book about the physiology of sleep, we’ll use a simple but nonetheless accurate sleep model that distinguishes between states of relative activity while asleep: deep sleep, dreaming sleep, and sleepwalking. During a night’s sleep, the states might vary on a cycle of activity as shown in Figure 2.1 (sleepwalking is in parentheses because it doesn’t affect everyone):

Figure 2.1

SLEEP, WAKING SLEEP, AND WAKING UP

Then the alarm rings, and you wake up, get out of bed, and start preparing for the day. But how awake are you? Are you conscious of washing, dressing, and having breakfast, or is it all happening on autopilot? All the while you may be thinking about what you need to do today, whom you may meet, and so on. You’d probably call this “planning.” Dressing, making breakfast, and the rest are things you’ve done every day for years, so they don’t require much thought, and you can focus your attention on your plans for the day. Problem is, you can become so engrossed in the plans that the toast burns and the eggs turn hard-boiled!

There is a popular idea that you can multitask, but that’s a myth. The only tasks you can continue to do while thinking about other things are completely automated ones, and even then you’re not actually multitasking. What’s happening is that you’re switching your attention from one thing to another so quickly it looks as though you’re doing more than one action at the same time. So-called multitaskers are actually rapid attention-switchers. You can see how this works with breakfast preparation. Although the eggs seem to boil without your attention, every now and then, you check the timer to see how long they’ve been in the water, if only fleetingly, and you are hardly aware of doing so. But if you’re making breakfast for a guest who eats completely different food from you that you’re not used to preparing, your attention has to be focused completely on these novel tasks if you’re to do them properly. You’ll still be planning, but only as far as the next step in the breakfast you’re making.

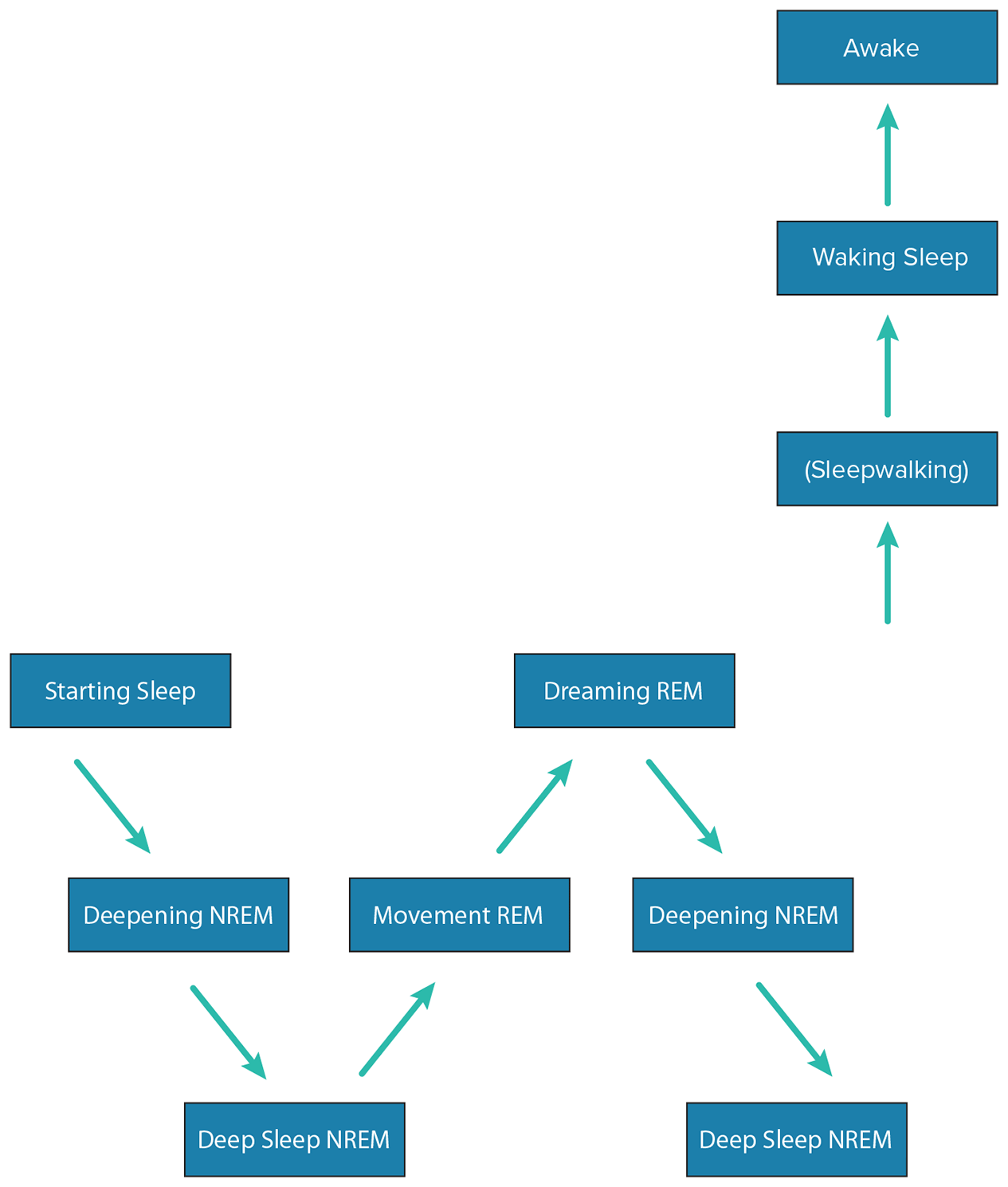

What varies all the time in the process of performing tasks is the extent to which we control and give attention. Our simple breakfast example of burning the toast and inadvertently hard-boiling the eggs shows the inefficiency that results from losing control of attention—in this case, allowing it to be hijacked by thoughts about the rest of the day. We need names for these different states, so let’s extend our continuum of sleep. There is deep sleep, which more or less refers to unconsciousness. There is dreaming sleep, which refers to a state in which there is mental activity but partial bodily paralysis. And there is sleepwalking, which refers to a state in which there are complex actions. When we’re seemingly awake but have had our attention snatched away, that we call waking sleep. As shown in Figure 2.2, being fully awake comes only after waking sleep.

Figure 2.2

Being awake can take different forms. In emergencies, people will often behave absolutely appropriately without having had any prior experience of what they’re going through, and they’ll often say that everything seemed to be happening in slow motion—they had time to react to what was unfolding. The key to this state is that you’re completely in the here and now, which is why we describe people who behave appropriately in emergencies as having presence of mind—literally, your mind (or rather your attention) is in the present. In these circumstances there’s no time to think about what others have done in similar situations, and all the information you need is gained from the present moment.

The reaction pattern we see in emergencies is sometimes described as the fight-or-flight response, but there is also a freeze reaction. What people say when fight or flight kicks in is that they experience no fear at all—the fear of what might have happened often only occurs afterward—but when people freeze, the emotion has caught them before they can begin to act. Derek’s experience of this was being in a multistory parking garage during a major earthquake when he saw some people rigid with fear behind the wheel in their cars, completely unable to act.

Emergencies like earthquakes are quite rare, and the more common experience of being awake is when people are able to draw on remembered experience and formulate plans for action, while maintaining the present as the frame of reference. When pressure is high, this calculation needs to be done quickly, but our brains are perfectly capable of that. The sorts of situations we find ourselves in at work typically will range from high-pressure, quick decision making to deliberate thinking and planning, but the common key feature is that we’re intentionally and consciously using the past and the future to make sense of the present. This purposeful planning, referring to the past and future but keeping the present as the frame of reference, we’ll call reflection.

Waking sleep is the same as becoming engrossed in a daydream. Everyone does it, but the question is, how much time do you spend in it? Waking sleep varies from person to person, and it depends on factors such as how tired we are. Here are scenarios to illustrate waking sleep. Think back to the last time you were on the road and you reached Town X. The next thing you knew, you were in Town Y, 20 miles farther, with little or no recollection of the journey between the two towns. Or you might have gotten up in the morning and somehow arrived at work, but you did not remember getting ready and traveling the route. Perhaps you listened to the news on the car radio while waiting for the weather forecast, but five minutes later you realized that you had completely missed the forecast. During these times, between towns or between work and home, where were you?

Sometimes people say they were a blank, but you’re only more or less a blank when you’re in deep sleep and only definitely a blank when you’re dead. Practically speaking, what you were actually doing was thinking about the past and the future. “What was that meeting about yesterday?” “What am I planning to do today?” “What do I need to finish that project?” “How can I engineer a meeting with so-and-so?” When these thoughts are about something in the future, we have some expectations, hopes, or fears about what might happen, which may or may not occur. To that extent, the future is fantasy. As it happens, the past is also fantasy. Bear with us while we explain.

What we call “my life” is a story we create. Everything we experience passes through the screen of our conditioned view of the world. For almost every situation, the people who experienced it will have differing versions of what happened. A simple example is the experience of people in a training program—they all heard the same presentation, but each will recall something different from what was said. Ask two people who grew up in the same family about their childhood—the versions can be so different that they might as well have been different families! The conditioned, programmed way we live much of our lives is obvious in so many simple situations. We move offices from the fifth to the seventh floor, but how often do we continue to take the elevator to the fifth floor after the move?

This is not to say events don’t happen. Individuals just have different perceptions of the event because of their different associations and conditioning. What you think happened in any given situation is your version, usually with additions and omissions. They are, after all, just thoughts about what you think happened in the past or what might happen in the future. All of it can be described as fantasy, and if these thoughts are fantasies, then they must be dreams. And if they are dreams, you must still be asleep. You may be barreling down the road at 70 miles per hour, but you’re in just another level of sleep: waking sleep.

You might wonder why there aren’t many more road accidents than there are. Fortunately, there is usually a part of our attention that continues to monitor what’s happening, and it responds to change. Each time something changes—a car pulling out ahead, for example—we’re drawn out of the dream, and we usually respond appropriately. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work, and our engagement in the dreamworld can be so complete that we don’t wake up in time. Driving while using a mobile phone is illegal for obvious reasons: your attention is on the conversation, and because you have to respond, your engagement in it can completely exclude what’s happening on the road in front of you. But what about the conversation you’re having in your head? That can be just as distracting. Learning to turn it off like a mobile phone is what our four steps are all about, and the first step has to be waking up.

People will quite readily recognize waking sleep in themselves, and they can acknowledge the need to wake up, but a question we’re often asked is how do we wake ourselves up? When we sleep at night, we can set an alarm, so how do we create an internal alarm? The first reminder that needs reiterating is that waking sleep happens to everyone: nobody is awake all the time. The aim is to be more awake more of the time, and the way to create an internal alarm is to practice staying awake whenever you do wake up. If you do this, your mind will begin to develop the habit of waking up instead of going to sleep.

We can start by discovering what it feels like to wake up. Wherever you might be while you’re reading this, stop reading for a moment and just listen. Try to focus your attention only on the sounds you can hear now, in the moment. Notice that you’ll want to classify the sound—for example, noting what kind of bird you may be hearing. This is to be expected because that’s how we make sense of the world, but stop there and return to just listening. Try not to elaborate on what you are hearing into the memory of the last time you heard it, or what it reminds you of. Just listen, as closely as you can.

We often have training audiences try this exercise, asking them to listen to the sound of our voice when we’re speaking, and when we’re not speaking, to listen to any other sound they may hear. The atmosphere in the room changes completely, so much so that we’re sometimes accused of having hypnotized everyone! We so seldom bring our minds to stillness, just registering without creating stories, that it can be quite startling. Hopefully, you’ve just had a taste of what it feels like to be in the present and awake. It might not last very long before the mind noise starts up again, but that’s to be expected: your mind needs to be entertained, so if you don’t give it something to play with, it will go off and find something. Nobody can be awake and in the present moment all the time. The key is to stay awake for as long as you can whenever you do wake up, without any self-criticism when you find you’ve drifted off again.

The easiest way to stay in the present is to connect with your senses. That’s because your senses work only in the present: you can’t see or hear anything yesterday or tomorrow. These are just thoughts about what happened or might happen. Connecting with your senses connects you with the present, and although listening tends to be easiest, the same is true for any of your senses. Remain connected as long as you can. That reinforces the habit of waking up instead of the habit of waking sleep, and you’ll find yourself waking up naturally from waking sleep more and more frequently and being able to stay awake for longer each time.

Being awake doesn’t require stopping what you’re doing. You can connect with whatever is in the present, and that includes whatever piece of work you might have in front of you. If you don’t connect with what’s in front of you, then it isn’t getting done. Do you get to the end of a piece of work and before beginning the next one, do you start thinking about next weekend? You may intend to do it for only 5 minutes, but it’s more likely you’ll wake up from the dream about next weekend 20 minutes later, by which time you’re way behind schedule. Everyone does it, but there is a cost.

Here’s a scenario: A report, endlessly amended, is doing the rounds and is back on your desk. You groan inwardly, but you start reading. In no time at all, you’re imagining where you might go for your next vacation. The reverie is interrupted by your manager, who wants to know if you’ve finished with your review and reminds you that you have to present it to the rest of the team in 10 minutes. Panic! You might manage to wing it, but all this unnecessary pressure has come about because of waking sleep: you spent your attention on the next vacation instead of attending to the report. How about the last time you were in a meeting and were asked by your boss, “What do you think about this?” when in fact you were thinking of your options for lunch. Panic!

At least some of these illustrative scenarios will be familiar, if not all of them. Our mind needs to be entertained, so it will wander off if we lose interest in what we’re doing. The efficiency cost involved is obvious: the more time you spend in waking sleep, the less you get done. We’ve acknowledged that no one is awake all the time, and repetitious tasks in particular are likely to lead to more waking sleep. We all have repetitious things to do, but the mistake is to plow on, trying to work against the growing boredom to get the job done. The result is diminishing returns and an increase in errors, which is why prolonged repetitious tasks need to be interspersed with frequent breaks to keep the mind fresh.

For almost any task you care to think of, there will be those who find it boring and others who find it interesting. That means that boring isn’t an inherent quality of the job but rather something you’ve attributed to it. The problem is that once you decide something’s boring, it will be! We tend to forget that the way we label things can make them self-fulfilling, just as saying how stressed we are all the time makes stress inevitable. Being bored with something is in part a decision you’ve made about it, although how quickly you become bored is in part hardwired, depending on where you are on the continuum from extravert to introvert. Extraverts require a greater degree of stimulation than introverts, but it is important to remember that extraversion-introversion has a bell-curved distribution: most people are toward the middle of the curve. Fortunately, extraversion is not implicated in resilience. We needn’t digress into a detailed discussion here, but for interested readers, a neuroscience model of extraversion/introversion can be found in the description of the research program in the Appendix.

THE NIGHTMARE: RUMINATION

We all recognize waking sleep, and we also recognize the panic that can come from being caught in our reverie. This leads to the next step after drifting into pleasurable waking sleep: the addition of negative emotion. After the meeting, are you preoccupied with what the rest of the team thinks about you? Do you continue to elaborate on the theme, worrying about what your boss might think, eventually ending in the nightmare scenario of losing your job, not being able to pay the mortgage, and leaving your family destitute? What you’ve moved into is a state of ruminating about emotional upset.

Rumination is the constant churning over of what-ifs and if-onlys. It’s what causes stress. Without rumination, there is no stress, and rumination serves no purpose at all. Far from being useful or good for you, the only consequence of choosing stress is a more miserable and possibly shorter life. This book is not about managing stress, as if it were inevitable. It’s about resilience, and resilient people don’t get stressed. We can now be more precise: resilient people don’t ruminate pointlessly about emotional upsets. Waking sleep is the idle dream, which unfortunately can be elaborated easily into the nightmare of rumination, but we can choose not to do it. The implications of making the choice are hugely significant, not just for individual well-being but for organizations as well. It is estimated that 15 million working days were lost to stress-related sickness absence in the United Kingdom in 2013, and sickness absence is thought to cost the U.S. economy $227 billion annually.

There are of course ill-health conditions that prevent people from working, which is primary sickness absence, but a significant proportion is also attributable to secondary absence: being well enough to return to work but deciding to take a sick day and stay at home. Sickness absence was the focus of a case study Derek conducted among serving police officers in the United Kingdom. The gold standard for assessing change as a result of interventions is a randomized controlled trial (RCT), which is the basis for testing any new medicine. Participants in the trial are all patients with the same illness, and they’re randomly allocated to either an experimental group that receives the drug or a control group that receives an ineffective substance made into tablets or capsules that look identical to the drug (the placebo). The patients are assigned randomly to one or the other group, and the key to who receives the drug and who receives the placebo is held in a computer file until after the study has been completed. Neither the patients nor the people administering the tablets know who receives what, which is why trials like this are called double-blind. At follow-up the patients are assessed to see whether there has been any change. The key is revealed only at this stage, and if the patients who actually received the drug show significant improvement in their condition compared to the controls, you can be confident that the drug has an effect on the condition.

It is difficult to create genuinely blind experimental and control conditions for training interventions, but it is possible to get a close approximation to an RCT. Our police participants were allocated to experimental and control conditions using systematic randomization: although allocation was randomized, factors such as age, gender, and length of years in service were controlled for to ensure that they were equally represented in each set of groups. One reason for working with a large employer like the police force was the substantial population from which to draw the samples based on these demographic factors. Consequently, we were able to assemble total samples of over 70 participants in each condition. For the study, they were broken down into training groups averaging 10 participants each.

Another reason for working with the police was that they had been using a conventional approach to stress management for some years. It was having little effect on the outcome measures they were using, including sickness absence, but it meant that there was a training program available that the participants were scheduled to attend at some stage. Studies of training or therapy interventions will often use waiting-list controls—people who are going to receive the training or therapy at some time in the future but who serve as control groups while waiting. The problem is that there’s no way of knowing what help or information they might receive in the meantime, and with tests of psychotherapies the problems might in any event spontaneously remit. In our study, the conventional stress management training already in place served as the dummy training, which the controls received at the same time and over the same period while the experimental groups received Challenge of Change Resilience Training. The study was arranged so that the two sets of groups did not have contact during the subsequent follow-up period.

The outcome measure was sickness absence, but occasions of primary or unavoidable sickness absence were excluded. Only instances of avoidable or secondary absence were used, and the participants were unaware that sickness absence was the outcome we were studying. Secondary sickness absence over the previous 11 months was assessed at baseline and again just under a year later, and the results showed significantly lower sickness absence for the experimental groups: the average absenteeism figure for participants in the experimental group that received Challenge of Change Resilience Training was 5.39 days over the initial 11-month follow-up period, while the average for the control group that received the dummy training was 10.96 days. The results are shown in the graph in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3

The graph shows that the sickness-absence rates increased for both groups, but this was a consequence of the 11-month inter-test interval spanning the winter months, when the incidence of seasonal minor illnesses that can compound secondary absence, such as common colds, showed a general overall increase. Controlling for seasonal effects, the control groups had significantly more days off than the experimentals, and the lower sickness-absence rate for the experimental groups was maintained through to an extended 18-month follow-up. Over the follow-up period the sickness-absence figures for the experimentals did increase slightly, but a booster session provided for a subsample from this group showed that it had the effect of reinstating the lower level of absence.

The case study of sickness absence among U.K. police officers was the first one that we conducted. The results were replicated in subsequent studies, such as an analysis of sickness absence among managers in a large nonprofit U.K. organization providing help for people with a range of mental and physical disabilities. For practical reasons, unlike the first study, it was impossible to create a control group, but comparisons were made between the sample of managers who received the training with the average data for the other managers in the organization. Comparing the sickness-absence rates for the trained and untrained managers for the six-month follow-up period of the study with the corresponding six-month period the previous year showed that sickness absence was reduced at follow-up by between 16 and 43 percent across the four sectors, compared with a change of just 0.25 percent for the organization as a whole.

Participants in the second case study were all managers in the organization. While developing resilience is a key skill for everyone, it can have even greater implications for organizations if their leaders are not resilient, so let’s consider what happens when the leaders of your organization are asleep most of the time.

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF LEADERS BEING ASLEEP?

Changing any behavior begins with awareness that it’s happening, so for leaders to be more present and awake with their teams, they first need to notice just how much of the time they are spending in a dream state, perhaps while speaking with their direct reports, sitting in a meeting, or listening to a conference call. Effective leaders we meet are seldom in a dream state—they tend to be much more awake, in the moment, and paying attention to their environment, their people, and the impact of their behaviors. In other words, they’ve learned how to wake up and stay awake more of the time.

What do more wakeful leaders look like? Comparing the waking-sleep behavior of resilient and effective leaders with that of less resilient ones, the contrast looks like this:

Skilled in Resilience

- Spend much of their time in the present moment, fully connected with the people they are talking to rather than daydreaming about something else

- Find the present moment interesting and are curious about what’s in front of them

- Realize that stories they have about the past may just be their personal version and that future plans are only possibilities

- Can quiet their minds, even amid the noise of the workplace

- See themselves as multidimensional, not defined by just one life area such as their career

- Focus on the things that they and their team can control or have influence over

Unskilled in Resilience

- Drift off into unrelated thoughts when others are talking to them and look disengaged in meetings

- Unaware of just how much time they spend daydreaming during the day

- Think so much about the future that they miss opportunities in front of them right now

- Fail to pick up on the body language of others and how they are feeling

- Focus mainly on outcomes, rather than the inputs that produce the outcomes

- Define themselves by their job: “If my work is criticized, it is a critique of me.”

Describing the problem is the easy part. The question is, what can you as a leader do to develop your resilience? Here are five strategies for leaders to reduce rumination, both for yourself and for your team.

1. Connect with your senses. The fastest way to wake up and come back to the present is to literally come to your senses: what you can hear, see, feel, taste, and smell. Try the exercise we described earlier, just for 30 seconds: listen to the sounds that are close to you and then the quieter ones in the background. Notice the weight of your feet on the floor, the temperature on your face, and the shapes and colors that are around you right now. You can do this only in the present, and when you connect fully, you’re wide awake. Try doing this several times in the next few days, and notice how it changes the quality of your presence.

2. Wake up the people around you. Most workplaces are full of people wandering around on autopilot, resulting in mindless meetings, inauthentic interactions, and a lack of real progress. The most effective leaders we know don’t follow along mindlessly. When they see people going through the motions in meetings, they wake them up, not in a way that would embarrass them but by asking the group provocative questions. Working with senior executive teams, one of our colleagues will often ask, “What’s the conversation you should be having right now but are avoiding?” People wake up, come back into the moment with their colleagues, and the energy rises. Look for these opportunities with direct reports and colleagues, to wake them up.

3. Ask direct reports questions about right now. Many people in workplaces suffer over things that are not actually happening. I (Nick) was talking to an orthopedic surgeon once about how her patients dealt with pain. She was fascinated by the ideas about waking sleep and rumination, and she mentioned how she had changed the questions she was asking her patients. She described one man who was constantly complaining of how painful his injury would be, and every time he did this, she asked him, “And how painful is the injury right now?” Often he noted that he wasn’t in any pain at that moment. The more she did it, the more he realized that while the injury was real, the suffering he was experiencing was mental rather than physical pain.

In the same way, we see many workers suffering over an organizational change by imagining the worst possible outcomes. They’re ruminating. When you see people caught up in the future like this, you can help short-circuit their thinking. The way to do it is not to dismiss their feelings but to bring the conversation to the question, “What problem are you experiencing, right now?” This offers something actual and practical you and they can work on directly.

4. Ask yourself, “What’s the opportunity in front of me right now?” One reason many can’t stay awake for very long is because they don’t value what’s in front of them. In one of our workshops, the CFO of a major airline told us that when his direct reports didn’t get to the point right away, his mind drifted off. In his 360 review, he received feedback about his drifting off, and he felt embarrassed, but he didn’t know how to change it.

By this time he had grasped the principle of waking sleep, so we asked him to start by considering what value or opportunity he was missing by falling asleep in the conversation. He laughed and acknowledged that he was missing the chance to coach, get to know, learn from, and influence them. “Are any of those of any value to a leader?” we asked. He had to admit that if he wasn’t doing those things, he wondered if he was much of a leader. We asked him what he might say to himself when he drifted off next time, and the question he chose was, “What is the opportunity I have with this person right now?” Following up later, he told us that not only did his direct reports notice that he was more present with them but so did his wife and children!

5. Start doing walk-and-talk meetings. One of the features of highly rated leaders is that their people feel comfortable sharing their emotions with them, whether positive or negative. However, the downside of expressing emotions freely is that sometimes people get stuck talking about the same old problem over and over, without moving to a solution. One of the most effective ways to break your direct reports out of this pattern is to get them to stand up and go for a walk and talk. The walk and talk doesn’t have to be long. In fact, it is better if it isn’t; 5 to 10 minutes is ideal. Breaking people out of their physical patterns—sitting in the same chair in the same office complaining about the same things—and getting them to move can break the cognitive pattern. It is hard for people to stay stuck mentally when they keep taking another step forward physically.

If you can go outside, all the better, because it redirects people’s attention from inward back out into the world. But that isn’t essential; walking around the office can be equally effective. One manager we work with does her walk and talks in the stairwell! The only rule is to keep walking. It’s not a stand and talk, nor a lean and talk. You want your people stepping forward. When the body moves, the mind will follow.

CASE IN POINT: BILL CLINTON AND LEADERSHIP PRESENCE

One of the things you often hear about great leaders such as Nelson Mandela or Mahatma Gandhi is that they have great presence. But what do we really mean by presence? We would suggest that the main reason that these leaders have presence is that they are present. When they meet you, their attention is not in their heads dreaming about last night’s dinner or something clever they want to say in the next meeting. They are present with you right now.

One of the examples that comes up often in U.S. training is that of Bill Clinton. People say that he walks through a crowded room shaking different people’s hands and when he comes to you, he looks you in the eye and you feel like . . . you are the only person in the room.

Great leaders have presence because they are present. What would people say about your presence? What would your coworkers say? What would your direct reports say? What would your family say?

Perhaps they would say, “It feels like he is giving me his complete attention.” Or perhaps they would say, “It feels like he wants to look at his phone.”

Reflect for a moment. What would the important people in your life say about your level of presence?

SUMMARY

- In a given 24-hour period, people are generally asleep for much of the time: either in ordinary sleep (deep sleep, dreaming sleep, or sleepwalking) or apparently awake but actually in waking sleep.

- Waking sleep is comparable to daydreaming, and like a dream at night, it seems real until you wake up from it.

- Waking sleep is commonplace, and it isn’t a problem unless there’s something in front of you that you’re supposed to be attending to. You can’t work and sleep, so the cost of waking sleep is inefficiency.

- Waking sleep is transformed into rumination when negative emotion is added—the what-ifs and if-onlys that serve no useful purpose and leave you feeling miserable. Rumination also prolongs the arousal required for attending to what is necessary. Your body will naturally return to a resting level so that it can recuperate, but rumination interferes with the process and prolongs the strain of the arousal to the point where it will compromise health.

- Waking sleep is not intentional. Our mind wanders into the past or the future. Being awake is about being in the present, which is why the easiest way to wake up is to connect with your senses—they operate only in the present. You can then intentionally draw on past experience and make plans for the future while keeping the present as the frame of reference. This is called reflection.

- Habitual rumination in leaders will significantly compromise a team’s productivity and happiness.

- As a wakeful leader, reduce rumination by doing the following:

- Connect with your senses.

- Wake up the people around you.

- Ask direct reports questions about right now.

- Ask yourself, “What’s the opportunity in front of me right now?”

- Start doing walk-and-talk meetings.