6

RESILIENT COMMUNICATION AND LEADING CHANGE

This chapter represents a shift from discussing the personal aspects of resilience to focusing on the interpersonal ones. We will not be digressing into a review of communication skills training, other than to provide a context for exploring how we can apply the same four steps of waking up, controlling attention, becoming detached, and letting go to developing more effective ways to communicate. A key element in facilitating change is being able to communicate effectively, and good communication is especially important in avoiding misunderstandings between managers and their teams. These communication techniques will enable managers to begin to behave more like leaders.

COMMUNICATION SKILLS: AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACH

Our interest in communication arose from a series of resilience training sessions we were running in a large U.K. company. Staff in the company was asked to complete an annual engagement survey, and although the results suggested that the overall climate in the company was good, it was patchy. There was a wide variation across teams, and the main contributor to low engagement seemed mainly to do with poor communication. Staff also uniformly reported that poor communication was contributing significantly to their feeling stressed as well as disengaged. Communication skills training was available for staff in the company, but it didn’t appear to be having any tangible effect, so we decided to include in the resilience program many of the communications skills we discuss in this chapter.

One way is to improve eye contact. When someone you’re talking to steadfastly looks over your shoulder, it can be very disconcerting, and the opposite may be true too: unwavering eye contact can make the conversation seem more like an interrogation. Maintaining appropriate eye contact is undoubtedly important, and a rule that is sometimes suggested is that it should be about 50 percent of the time. However, patterns of eye contact are highly variable, depending on factors such as how formal the conversation is or the complexity of the information being conveyed. When someone is reflecting on a proposal you’re suggesting, especially a complex one, he will often break eye contact, not because he has lost interest but because it is easier for him to reflect if he is not focused on you. Skilled communicators might use a wide range of eye-contact patterns within the same conversation.

Another feature of good communication skills is the ability to listen. This might seem obvious, yet most people have had the experience of talking to someone and seeing the blinds come down—the lights are on, but there’s no one home! Another way of thinking about this is attention control: when the blinds come down, attention has been pulled away to something else. However, this may be because your listener is reflecting on what you’ve said. She is going into the past or the future intentionally to make sense of the problem. The simple solution is to wait or to check whether clarification is needed.

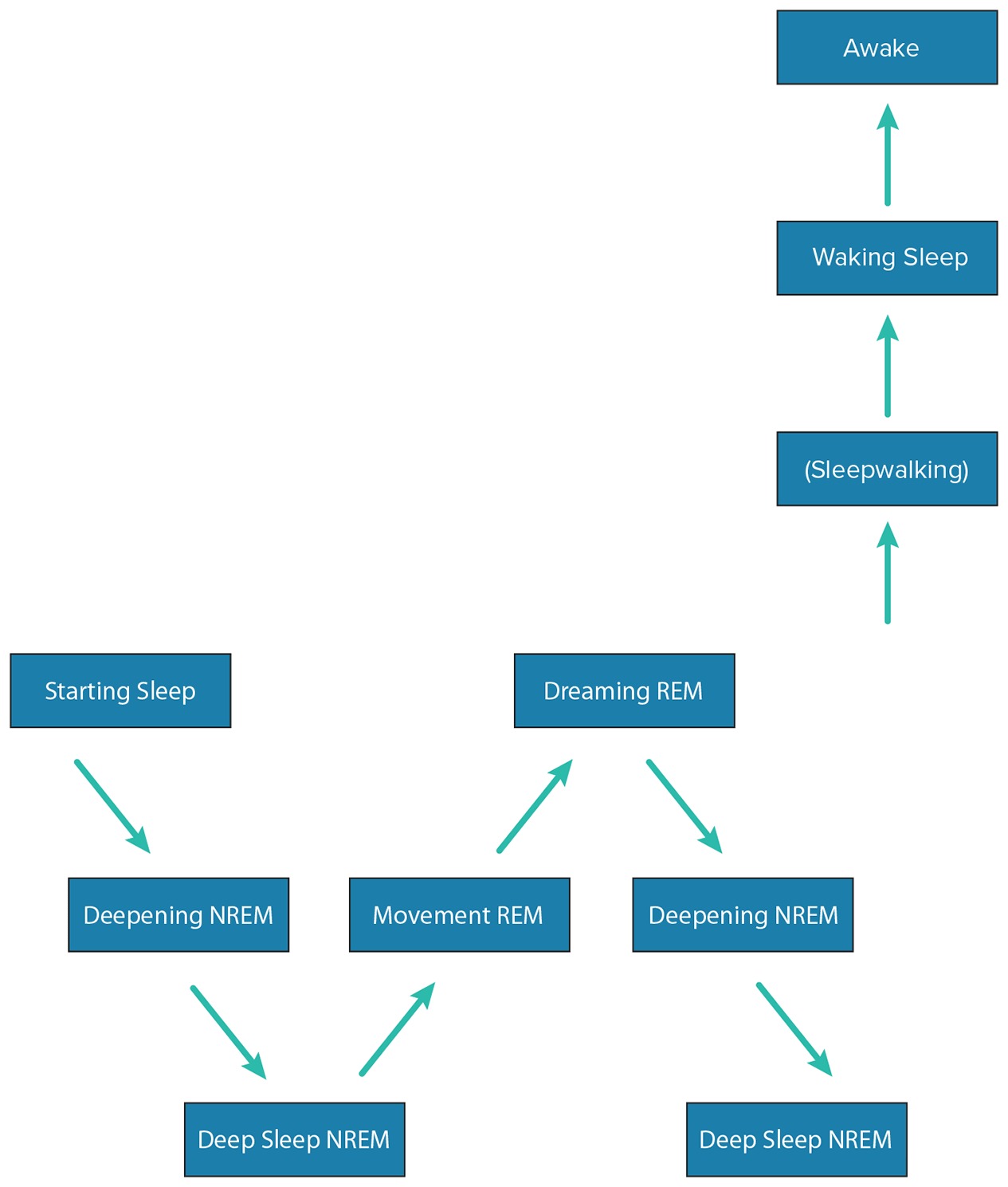

Then again your listener might have drifted into waking sleep. We all know that feeling of having heard it all before, and instead of listening, whatever we’re going to do next weekend becomes a lot more interesting. Worse still, if we’re being criticized, we might add negative emotion to the daydream and turn it into a nightmare of rumination. When attention is drawn away into waking sleep or rumination, your listener is effectively no longer there and you might as well talk to the wall.

Figure 6.1 is the same diagram we used in Chapter 2 (Figure 2.2) to show the changing states of waking and sleeping. In which of these states are you actually available and able to communicate? It has to be only when you’re awake. The first two steps in our system apply equally to communication: to do so effectively, you have to be awake and controlling your attention. Controlled attention means giving it to the here and now—in other words, listening to what is being said. Communication is disrupted by interference, which can take external or internal forms. An example of external disruption is when you’re speaking and someone interrupts you; internal disruption is losing attention control and drifting into waking sleep or rumination.

Figure 6.1

Communication is much more likely to provoke rumination when it involves a personal attack on someone, so another principle of communicating more effectively is to make it as impersonal as possible. Suppose you spend a lot of time preparing a project report, but it doesn’t meet the required standard. At the meeting, your manager has two broad options for telling you this: he can say either (1) that the work you submitted hasn’t reached the required standard or (2) that you have failed to reach the required standard.

The difference might seem trivial, until you consider the consequences. In the first option there is an acknowledgment that the work hasn’t met expectations, and the opportunity is available for your manager to find out whether you might need more help or further training in the required skills, or perhaps more experience at preparing project reports. In the second option you are personally blamed for the shortcoming in the work, which will inevitably provoke some combination of guilt, embarrassment, and anger, especially if the comments are made in front of colleagues. You might still do what’s needed, but it is very likely to be compromised because it is accompanied by rumination.

DEPERSONALIZING COMMUNICATION

Let’s suppose I work for you, in which case there are three elements in our relationship: you, me, and the work. In one possible scenario, I’m attached to the work that I do, so we could place me and my work on one side. On the other side is you. In this scenario there is a legitimate target, the work. You’re my manager, and part of your role is to evaluate what I do. However, if my work and I are merged, then whatever you say about the work not being up to snuff will apply to me as well. Your job is to evaluate what I do, but you’ve ended up also evaluating me, and that isn’t your role. My work needs to reach a certain standard, but I don’t—whatever you might think of me personally is not a factor. So there are two potential mistakes involved here: as my manager, you are using the shortcoming in my work to blame me, or I may assume that whatever you’re saying about my work also applies to me, even if that isn’t your intention. Worst of all, you might be intending to apportion blame while I’m actively taking it on.

In a second possible scenario, you and I are on the same side, and the work is on the other. What has happened is that I’ve become detached from the work and can let go of the personalizing that goes with thinking I am my job. You might say that this is letting go of ownership and responsibility, but the problem is with the language: responsibility carries an explicit sense of identification and blame. We certainly have tasks we’re required to fulfill, and we do them to the best of our abilities and within the constraints of time and money. Words such as ownership and responsibility are loaded with the potential for feeling failure and being blamed. Why do we feel we need to hold the sword of Damocles over people who are doing their best to achieve the goals we’ve set them? And why do we assume that if we don’t imply blame, we’ll be allowing others to get away with anything they like?

When people are given a task, there is an expectation that they’ll deliver. If they don’t, there is a reason for it—most people don’t intentionally do a bad job. In fact, one of the criteria for being a leader instead of a manager is to assume that everyone wants to do the best they can. Let’s take fault out of it altogether. If something doesn’t work out as planned, what can we—together, on the same side—do to try to ensure that it works out better next time? Before you engage in a blaming exercise, try asking yourself whether you’ve always done everything to perfection, and work from there. A blaming culture is informed by a fundamental belief that threat and blame get things done. As with toxic achieving managers, the job may get done, but at a significant cost to teamwork and loyalty.

A phrase that is commonly used to mask blame is constructive criticism, but criticism is never constructive. The phrase is a contradiction: constructing is putting together, while criticism is taking apart. Most people who have been on the receiving end of so-called constructive criticism will probably tell you they felt taken apart, and as a consequence, they ruminated about it afterward. People will often defend constructive criticism as a means for people to learn from their mistakes, but when you explore this further, it is apparent that there’s an implicit assumption that people feel guilty, so they won’t do it again, supposedly learning from guilt. Feeling guilty is a useless waste of attention. When you see that what you’ve done doesn’t reach the required standard, learning about it happens right then and there. Guilt is just a form of rumination. And what’s a mistake? A lack of practiced skill. How long did it take you to acquire the skills to be expert at what you do?

The negative effects of criticism might be unintentional, but saying you didn’t mean to have that effect doesn’t prevent it from happening. Communication needs to be mindful, so that you’re aware of the effects of what comes out of your mouth. This is one of the key differences between managers and leaders. Much of what passes for management training is about process, which is important, but anyone can do process. Leadership is quite different. People follow managers because they have to; they follow leaders because they want to. You don’t respect those whose default mode is criticism.

The principle of separating the person from the work is implicit in child-rearing. When children step out of line and misbehave, what do you comment on, the behavior or the child? Always the behavior, not the child. The appropriate response isn’t, “You idiot, what did you do that for?” but rather, “If you behave like that, it will upset people, so try not to do it again.” Criticism destroys self-esteem and turns people against you, which we know when we deal with our children. Why is it thrown out the window when we’re dealing with adults?

Behavior here is not what the child is but what he does, and that tacit assumption extends to our attitudes. If a member of your team has an attitude problem that’s affecting everyone else, take the person aside—this is always done privately—and point out that he has a way of behaving (acting or speaking) that is causing problems for the team. Reassure him that it is just a habit that he may not even be aware of, but it does need to change. Describe it as precisely as you can, and then give him the opportunity to change, with the further reassurance that if he finds it difficult, you can arrange for some individual mentoring for him. An important qualification is not to expect change overnight. A caveat: There are those who habitually take things personally. If they are on your team, use extra care when dealing with them. A feature of good leadership is not assuming that one style fits all—people are individuals, and they have to be dealt with accordingly. Learning to be resilient can go a long way toward addressing people’s self-perceptions, and the training program is in part about enhancing self-esteem. But when dealing with those who find it difficult to change, your expectations need to be realistic.

The effects of habitual attitudes and behavior are even more important for managers because the way they act will directly affect all of the members of their teams. Based on the resilience training, there are specific steps that can be taken to address management style and to transform mere managers into leaders.

LEADING CHANGE

The two interrelated conditions under which people in organizations are more likely to ruminate are high uncertainty and a perceived lack of control. Because both conditions are common during times of large-scale change, it is important that leaders communicate in a way that reduces rather than fuels these conditions. Leaders themselves are usually experiencing the same challenges as their people, so they need to be particularly mindful not just of the words they use but also their body language and tone of voice: they may be communicating more than they think. The way we communicate becomes so automated and habitual that we may not be aware of what skilled communication looks like, but it can be systematically described:

Leaders Skilled in Communicating

- Consult those who will have to implement the change early to get their input

- Tell people what is currently known about the change and what is currently unknown

- Adjust communication style and level of detail to the needs of their audience

- Give people honest and clear feedback about their behaviors and their impact

- Help people make sense of what the change will mean to them

- Help direct reports work out what they can stop doing, not just what they need to add

- Hold frequent milestone meetings to focus on the change through to completion

Leaders Unskilled in Communicating

- Pass on information about the change from above, but don’t translate what that means at different levels

- Rush the implementation of the change without paying attention to people’s reactions to it

- Make decisions that will affect the implementers without getting input and buy-in from them first

- Deliver feedback that focuses on the person rather than the work

- Talk constantly about the change, but not about everything that is staying constant

- Overfocus on the needs of the team, while neglecting to look after themselves

The key to being a true leader is not just being able to drive for results. Working effectively with people is as much about how well you can communicate, and people skills are a significant part of what makes the difference. People will follow leaders willingly because they respect them, and that respect comes primarily from their people skills. The term business acumen is widely used and is generally assumed to be about financial literacy. One of the Challenge of Change Resilience Training providers in New Zealand, Cynthia Johnson, decided to dig a little deeper by conducting detailed interviews with successful CEOs. Factor analyzing their responses yielded a clear structure that included financial literacy but as only one factor; the other two were passion for the job and having people skills.

Teams generally have a structure that can be expressed in a tree diagram, with diminishing authority as you move lower down the tree and with clear labels for each level and each role. For example, a sales team might have a single senior sales manager at the top, with the next level having perhaps five managers each responsible for different sales areas across the country. They will in turn have salespeople reporting to them, each responsible for a different geographic area, as well as various administrative staff. The tree is the formal organization, and it describes how the different roles relate to one another and what their levels of status or influence are. Unfortunately, what the diagram doesn’t show is the informal structure: who gets along with whom, which people or teams are competing with one another, how effective each of the managers is, and so on. A significant determinant of informal structure is the behavior of team leaders. Here are some specific strategies that can be used to improve leaders’ communication skills.

1. Communicate the four Ps of the change. When a change happens in an organization, people can struggle to make sense of what it means for them. If a leader can help them do this quickly and efficiently, the team can avoid hours, days, or weeks of ruminative thinking. William Bridges, a leading researcher on change, points out that there are 4 Ps that people want to know during any change:

Purpose. “Why are we making this change? What is the rationale behind it?”

Picture. “What is the end state we are trying to get to?”

Plan. “What are the steps we need to take to get there?”

Part. “What is my role in the change? How do I help?”

Leaders who fail to answer these questions for their people leave a vacuum of uncertainty, which often is filled with rumination. Whenever you are leading a change, begin by communicating with your people about what the four Ps are for this change and for them.

2. Talk more about what is not changing. During new organizational initiatives, leaders often are told that they should be communicating constantly about the change. While this initially sounds right, our experience is that it often leads to unnecessary anxiety as people come to believe that more is changing in the organization than really is. The fact is that during most change initiatives, the majority of things will stay exactly the same: you will work at the same desk, sit with the same people, and use the same computer to do the same job.

The paradox for the leader is that the bigger the change, the more you have to emphasize what is stable. When Nelson Mandela led South Africa through the end of apartheid, the greatest challenge he faced wasn’t getting the change to happen but creating enough stability that the nation didn’t shatter. So when you are leading change, give as much emphasis to what is staying the same as to what is changing.

3. Identify the organization’s change equation. Researchers who study change estimate that as much as 70 percent of all change efforts fail to achieve what they set out to do. Given the significant amount of time, money, and effort wasted on these failures, you’d think that organizations would be analyzing their data to find out what distinguishes the successful change initiatives from the failures, but most organizations are simply too busy to take the time to do the analyses.

To help resolve the problem, we initiated a research project to help organizations do just that. Our research showed that there was no generic set of factors that applied to all organizations: organizational cultures vary so much that what leads to success at one company might get you fired at another. In some cases change is more successful when leaders are consultative, in others when they’re more directive, and in others still when it is less about the leaders and more about the people who will enact the change. Unless you can systematically unpack how your organization really works, it can be difficult to craft a change strategy. To find out more about what your organization’s change equation might look like, visit http://bit.ly/1OlH1wh.

4. Beware of the weeds. Recently we were working with a team from an engineering company who were particularly skilled at finding problems and trying to solve them. This made them good at their jobs, but it was problematic in meetings because every time someone mentioned a challenge, everyone would dive straight into the details and start trying to solve it immediately. The effect was that they often got lost in the weeds. After watching them get stuck several times, we pointed this out to them. They recognized it as a habit they had and wondered what sort of training they would need to overcome it. “No training needed,” we replied, “just call ‘Weeds.’ The problem is not that you don’t know how to pull yourself out of it. Your problem is that you don’t alert each other quickly enough when you are doing it. The next time someone on the team spots that you’re getting stuck in the details, just call out, ‘Weeds.’”

Over the next two days whenever a team member called “Weeds,” everyone would laugh, nod, and refocus on the bigger picture. All teams have habits that they fall into, which often have to do with their professional training. Leaders must point this out to their teams and have a word or phrase to remind them, “We are doing it again.” What are the habits that you notice in your team or company culture that need to be called out?

5. Acknowledge self-motivation: an antidote to micromanaging. Managers sometimes complain that one or more of their staff is not sufficiently motivated. People do make wrong decisions about their careers, they end up in jobs they’re no longer passionate about, or they have too large a workload and feel unsupported. Instead of complaining about the lack of motivation, find out why. The first principle here is to assume that everyone wants to do his or her best. If that’s the case, what’s become the obstacle to that happening?

If you respect your people and they respect you, then when you arrange to meet a team member to find out why she seems to have gone off the rails, the conversation will not be predicated on blame but rather a genuine effort to help, both for her benefit and that of the team. You might discover she is having a hard time personally. Since it has nothing to do directly with work, it might not be your business, but the effects of rumination are seldom compartmentalized. They leak into work from home and from home to work, so offering avenues to help is in everyone’s interests. Maybe this person isn’t actually able to do the job she has been given, but she has been reluctant to acknowledge it. In which case, arrange for specific practical help, such as more training.

Perhaps this person has just ended up in the wrong place and needs a change. You can try to find a more appropriate position for her in the company, though it might also be that the time has come for her to move on. A manager in one company we worked with had joined in the role of an archivist, but he had become a manager, which he definitely didn’t want to do. He listened very attentively during the Challenge of Change Resilience Training program. A week later, he submitted his resignation. When asked why, he said it was because of the program—it had given him the courage to make the move. Prior to that, each time he thought about moving, he catastrophized everything, imagining himself jobless, impoverished, and begging on the streets—the worst things in our lives that generally don’t happen.

He worked for an enlightened organization that recognized that he no longer fit the role, and they actively helped him make the transition. We were working for the same company a while later, and he called to say that he had found a job running an antiquarian bookshop, which he loved. He’d taken a pay cut, but he and his family were happy once again. You can’t buy happiness, and no amount of misery is worth putting up with for the sake of the money. It goes without saying that a drastic move should be based on a strategic plan and not just a whim, and there are not always jobs available that you can shift to, but the major obstacle to change is fear. The reason you’re unhappy might also be because you’re a professional ruminator, and since you take your mind with you wherever you go, you might be just as unhappy in the new job—not because of the job but because of your habitual tendency to ruminate!

Assuming that people want to do the best they can is also a powerful antidote to micromanagement. The reason to micromanage is that these managers don’t trust their team. Managers have to set the strategies and the goals very clearly, but after that, they need to get out of the way and become interested bystanders—monitor progress, be available to provide help, but intervene only when necessary. In fact, if your people trust you, they won’t go on pretending they’re coping with the job, and they will let you know when they need help. And when you have to intervene, do so from the perspective of detached compassion, which allows an objective evaluation of the way people set about solving problems. There are many routes to the same outcome, but micromanagers think there’s just one right way—theirs!

6. Become counselors. To become effective leaders, managers should be counselors. What this doesn’t mean is having an open door for people to talk endlessly about their personal problems. If someone is struggling with personal issues, he may well need professional counseling. Instead, we’re using the term counseling generically. A team is not a homogeneous entity but a collection of often very different people. Managers need to acquire the skills that counselors employ.

We know from our own research that real people skills include the appropriate expression of emotion and cultivating detached compassion, both cornerstones of resilient leadership. Empathize with the problems people encounter without becoming personally involved. Counseling is also a private matter, so when mistakes need correcting, always do so privately. Ask yourself whether you’ve ever failed to deliver—even with the best of intentions, sometimes we just run out of time or resources.

7. Avoid giving team members things to ruminate about. Criticism is almost always perceived as an attack on our self-esteem, and the consequence of criticism will inevitably be rumination by the person on the receiving end. Criticism is never constructive, so avoid giving people things to ruminate about.

There was a performance issue with a member of one of the teams we were working with. The team leader happened to be rushing between meetings when he bumped into this person. All he said was, “There’s some good news and some bad news!” and he went off to his next meeting. The team member had a tendency to ruminate anyway, and all he reported doing for the next week until he could get clarification was to ruminate endlessly about what the bad news might be. This was a consequence of mindless (as opposed to mindful) communication.

As it happens this team leader wasn’t a particularly poor manager, but he had a strong tendency toward impulsive extraversion. Impulsive extraverts tend to speak before they’ve engaged their minds. Giving his team member something to ruminate about was an inadvertent consequence of this particular manager’s personality. However, it shouldn’t be taken as an excuse. Even though extraversion has a significant genetic component, extraverts are nonetheless able to act more mindfully. Speech is preceded by thoughts—what we say is formulated in our minds—and using mindful communication means being aware of what’s forming in our minds and making a strategic decision about whether or not to say it.

What is worrisome is the number of managers who mistakenly believe that the recipients of their criticism will learn something from it. Instead, what the recipients learn is guilt and fear of making a mistake in the future, which may lead to pretending everything is going fine with a project even when it’s not, in fear of further criticism. All that they’ve gained is more grist for the rumination mill, and they certainly won’t respect their managers. The remedy for this kind of inappropriate managerial behavior can be as simple as saying, “This could be approached in a different way, which should produce a better outcome” instead of, “You’ve done this completely wrong. It’s just a mess.” One important caveat, though, is that you can’t just change the way you speak. If the attitude you’re holding in your mind is that people learn from being called out, then the superficial change in speech won’t fool anyone.

8. Depersonalize communication. Depersonalize communication by making a distinction between the person and her work. Comment only on the work. This all seems self-evident, but we’re constantly surprised by managers who forget the principle of child-rearing—comment on the behavior, not the child—and vent their frustration and anger on their teams. When employees report in engagement surveys that communication in a company is poor, what they’re most often referring to are managers who have created a blaming culture. Blaming cultures are not worth staying in.

SUMMARY

- Poor communication is one of the major contributors to disengagement and rumination among staff.

- Reframe communication based on the four steps in the Challenge of Change Resilience Training program: wake up, control attention, become detached, and let go.

- Communication has particular implications for leaders because of how it affects teams.

- Resilient leaders:

- Communicate the four Ps of the change.

- Talk more about what is not changing.

- Identify the organization’s change equation.

- Beware of the weeds.

- Acknowledge self-motivation.

- Become counselors.

- Avoid giving team members things to ruminate about.

- Depersonalize communication.