67

Chapter 6

MEETINGS: THE INVOLVEMENT EDGE

Most people consider meetings time-wasting, energy-draining, and spirit-sapping. Many of us would rather go to the dentist than attend another meeting. Nearly everyone complains about meetings. Most of us seek to reduce the pain by avoiding them or eliminating them—thus dealing with the symptoms, not the problem.

Meetings are miniature involvement processes and as such have highly symbolic value above and beyond the purpose they are called for. It is in meetings where people directly experience involvement. It is here that they learn where the work is headed, decide if the work is worth doing, and find out if their voices count. Low-involvement meetings sap energy while high-involvement meetings produce energy.

68

Every time we meet represents an opportunity to create and strengthen involvement. In these encounters, people decide whether to remain on board or to walk away, whether to push hard for success or to let things drift, whether to give their all to the project or allow distractions and other commitments to dissipate their energies.

If we want meetings to be dynamic, energy producing, exciting experiences that get things done, then instead of eliminating them we need to focus on making them positive experiences. Instead of working toward reducing the time we spend with each other we need to focus on how to make the time we spend together productive.

A New Blueprint for Meetings

Because we see meetings as involvement opportunities, we look beyond the typical notions of what makes for a good meeting. It’s not that agendas and efficient meeting structures aren’t important; it’s just that we don’t think they are enough. Meetings need to be more than something people endure, they need to create energy to get things done.

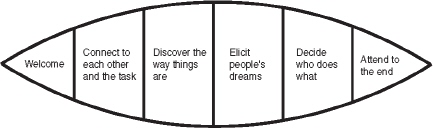

To help with this task, we have created a meeting blueprint (Figure 6.1). This canoe-shaped blueprint helps create meetings with an “involvement edge.” This canoe shape represents the opening up and closing down of a conversation. It is the boat that takes us from the beginning to the end of our time together. When we begin a meeting, the conversation is at its narrowest point. It gradually expands as we develop a clear picture of where we are and where we want to go. It is at this point that the most choices are on the table. The danger at this point is rushing to a conclusion before fully exploring where you are and where you want to go and thereby missing important opportunities. At the same time, you can’t explore options forever. The conversation narrows as we make decisions and decide what to do and who does what. Finally, it closes down as we review our decisions and assignments and say goodbye.

Let’s explore the elements of our canoe in detail.

69

FIGURE 6.1

THE MEETING CANOE

Start by Making People Feel Welcome. Foyers are designed to help people make the transition from the outside world to the inner world of our homes. In a similar manner, we need to assist people in making a transition from what they have been doing into our meeting. Here are some things to consider that help people feel welcome.

Pay attention to the room. The room sets the stage and influences what happens. Try to work in a room with natural light and plenty of wall space. Make sure everyone can see and hear what’s going on; straining to listen drains energy away from the work that needs to be done. And make sure the room is large enough to let everyone breathe.

Pay attention to how people are seated. Seating participants in a circle is usually optimal. The circle represents the most ancient form of interaction as well as a statement of egalitarian spirit. We recommend avoiding hierarchical arrangements, like lining people up in rows or seating them at long rectangular tables. Semicircles work well when the key challenge is to “face the issue.” People seated in a semicircle are able to face both one another and the plan that is posted on the wall. We also conduct stand-up meetings occasionally. When people are on their feet, the energy shifts and the mood changes. But stand-up meetings must be short, of course!

70

Pay attention to how you greet people. Your welcome can be as simple as a handshake or as elaborate as having a string quartet playing to create a mood of harmony and peace. The lobby might feature a simple banner announcing the meeting or a troupe of actors performing mime. Whatever kind of welcome you plan, it should make people feel special as soon as they arrive.

You already know how to make people feel special. You do it in your homes all the time. Think about the last time you had guests for dinner or an overnight stay. You took special care to clean your house beforehand. When your guests arrived, you greeted them in your foyer or on the front porch steps. You offered them tea, coffee, or a snack, as well as a comfortable seat in which to rest their weary bones. Each of these gestures demonstrated that you considered them honored guests, to be treated with dignity, courtesy, and warmth.

Now think back to the most memorable gatherings or social events you’ve experienced. Chances are good that the welcome you received was something special. We know a company that held a meeting for all its employees to celebrate an important new business initiative. To set the tone, the meeting planners constructed a tunnel for people to walk through as they entered the meeting. The walls of the tunnel were decorated with pictures depicting the company’s history from its founding to the present day. What a remarkable way to send the message “Our company is a unique and wonderful organization—and all of you are an important part of it.”

Find Ways to Create Connections Among People. In the words of a saying coined by the faculty of the School for Applied Leadership, “Connection before content.” In other words, before people can work together, they must feel connected.

Seeking connections is as natural as breathing. We do it whenever we meet someone new: “Where were you born? Where did you go to school? Do you know so-and-so?” We search for what we have in common so that we can feel more comfortable together. Finding something in common relaxes us and begins the process of transforming strangers into colleagues, partners, and friends.

71

Conversations help us connect. Some groups we know start their meetings by asking everyone, “What do you need to say in order to be fully present at this meeting?” A quick once around the room with everyone providing a response allows people to “clear their minds” and they are able to bring their whole selves to the gathering.

Personal questions are powerful ways to deepen our connections. They make us uncomfortable, and they make us think. We use questions such as, “Why did you come to this meeting? Why are you staying?” “What are you willing to do to contribute to the success of this meeting? What are you not willing to do?” “What acts of courage will our work require of us?”

As important as it is to connect with others in the room, it is also important to connect to the purpose, our reason for coming together. A common frustration experienced by meeting planners is to bring people together, make a presentation on the importance of what needs to be done, and then be met by silence.

Here is a pattern we frequently observe that we believe is at the root of the problem. The presenter will spend fifty-five minutes of the one-hour meeting making a presentation about why the topic is important. With five minutes to go the presenter will ask if there are any questions. Not wanting to be the only person who stands between the group and getting out of the meeting on time, no one dares raise their hand.

We suggest reallocating time by taking no more than twenty minutes to present information and then using the remaining amount of time for question and answer and discussion. Before starting a question-and-answer session, have people discuss their questions together first. This process of reflecting with others before asking produces better questions and helps the process go smoothly.

Reflecting first can also be used to stimulate discussion. After making a presentation, you can ask those present to reflect together on what interests them about what you have said, what they want to know more about.

When making presentations, avoid death by PowerPoint. A presentation using PowerPoint slides can be a powerful way of conveying information visually. But sitting in the dark looking at images on a screen encourages passivity. Use PowerPoint sparingly and keep it interesting.

72

Discover the Way Things Are—Build a Shared Picture of the Current Situation. A common concern we hear is, if we bring different people together the meeting will degenerate into a shouting match with everyone advocating their point of view, not listening to or incorporating others’ views. That is because leaders see things one way, followers another. Customers or clients have their own perspective. Outsiders such as neighbors or members of competing organizations have yet another view.

The easiest way to get started building this baseline is to ask people to explain to each other how they do their job. Individual answers will teach everyone about the challenges they meet on a daily basis. Taken together, they’ll reveal how the whole system operates. When people understand how the whole system operates, they become more willing to develop solutions that support the whole system operating effectively.

Suppose you are working with your school’s Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) to improve the nutritional content of the food served in the cafeteria. You might start your search for common understanding by asking the various people involved in the issue to talk about it from their perspective. The cooks might talk about the limited supplies they have to work with and the time pressures they are under. The school administrators might talk about federal guidelines that have to be met and the budget constraints they are under. The parents might be worried about the fat, salt, and sugar content in the food, without which the students might complain that the food is boring. Each of these perspectives represents a piece of a puzzle. Put them all together and you get the whole picture that needs to be examined if meaningful solutions are to be found.

Another approach is to foster curiosity by asking people to break down and reassemble ideas. For example, a group studied the systems in a hospital by designating one person as a patient. Wearing a sandwich board, this patient traveled from table to table, each table representing a different hospital procedure. At each table, participants wrote a description of what they would do to the patient and posted it on the sandwich board. By the end of the activity, the notes on the sandwich board represented the full patient experience as defined by the entire group.

Another approach is to help people discover what they already know. During a company meeting at a firm that needed to reshape its corporate culture, we asked people to describe their first day on the job. As people told their stories, they uncovered the history of the organization, teaching one another how things came to be.

73

The previously mentioned approaches support people sharing issues and ideas with people they usually don’t talk to. This means creating conversations that cross traditional boundaries—managers talking with employees, the sales department talking with manufacturing, and townspeople talking with the plant manager. It means teachers, parents, and students talking together about curriculum issues. It means doctors, nurses, patients, and insurance company executives talking together about the quality of health care.

When people come together to share their views of the world in this way, the lights go on.

Elicit People’s Dreams—Build a Shared Picture of Where You Want to Go. Have you ever noticed that when you decide that you want to buy a new car you begin to see that car everywhere? Having a clear picture of the current situation (you need a new car), and a clear picture of where you want to go (own a new car), your brain lets in new information. Now those cars were always out there, but because you’ve established a clear picture of the future you want to create your brain begins to see possibilities you didn’t see before.

We’ve found the arts to be powerful tools for creating a picture of where people want to go. Artistic talent isn’t required—just the willingness to share a personal vision of the future.

For example, you might invite the members of your team to make simple drawings that capture an aspect of the future they dream of. Even crude sketches can carry powerful messages about the future.

Sometimes we ask people to create short skits that show them five years in the future. As they act out the future, they show us how things could be, giving life to their imaginations.

Creating “living sculptures” is another approach. Once when we were working with a group of people in the midst of creating a new organization, we asked them to become the organization chart, standing in the groupings called for. As the new organizational arrangements came to life, the team members discovered what they liked and didn’t like about their plans for the future.

Writing can also be used to uncover the future. Try asking people to imagine themselves five years in the future and spend just five minutes writing about what they see in a free-flowing, open-ended style. The insights that emerge may surprise you.

74

Perhaps you’re dubious about using the arts in this way. We’ve found that most people are willing to participate in exercises like these as long as they understand that artistic talent is not required. The secret is to say, “This is not about art. We are not here to judge the final results. We want to use drawing [or skits, or writing] as a way of uncovering the future.”

If you still shy away from the artistic approach, try simple conversation. Invite people to pretend it is five years from today. Ask them to discuss what they are doing, how they are working together, what their new workplace, church, school, or community looks like. The key is to conduct the conversation in the present tense, as if the future is now— discussing not how you would like it to be, but rather how it “is.”

Many varied observations will emerge from this discussion, but in time some common themes will emerge. These themes represent the shared picture of the future—the goal toward which your work will be directed.

Encourage creativity as you build your shared pictures of where you are and where you want to go. We do this through a variety of methods. Exaggeration is one of them. For example, when working to improve the supply chain at an Air Force base, we asked participants to identify how they could sabotage the process. Exploring how to make the process fail provided ideas for what was needed to make the supply chain project a success.

Another approach is “single concept thinking.” In designing new organizations, we often ask participants to design the organization based on a single criterion such as customer service or quality. In this way, participants are able to delve deeply into that variable without worrying about other constraints. Later we ask people to integrate the best ideas from each category of single concept thinking.

Still another is the concept of an idea fair, in which people visit different booths where ideas are presented. Before leaving each booth, participants jot comments on a sticky note, which gives the idea creators lots of input from a variety of perspectives.

Decide on Who Does What to Create the Future You’ve Agreed Upon. Meeting leaders and participants often are frustrated about what happens when they come together to get things done. Instead of leaving with energy and enthusiasm, clear about where they are headed, they often leave confused about future direction. Unclear decision-making processes are often the cause. In order to prevent these negative outcomes there are three things to worry about here: the how of the decision, the what, and the who.

75

The group must know ahead of time how it’s going to decide. There are several options. The leader can simply decide; the leader can ask people to offer recommendations and then decide; or the group can make the decision jointly, with everyone having an equal voice. Any of these approaches can be valid. What’s most important is that the method you choose is clear and understood by all.

Identifying what needs to be done can be handled by simple brainstorming. Sometimes leaders already have an idea of what needs to be done. They can offer their own list as a starting place and ask people to add to or subtract from the list.

In other cases, the group will start from scratch. One technique we’ve found useful is to have everyone jot ideas of what needs to be done on sticky notes. Post all the notes on an easel or wall, and group similar notes together. Give each grouping a name and identify for each grouping the main task and the subtasks that need to be done.

Another approach is to create a time line on a giant sheet of paper taped to a wall. Invite people to identify what needs to be done and have them jot their ideas on sticky notes. Then have them place each idea on the time line at the point where it needs to be done. In this way a plan will emerge.

Finally, there is the who. Again, there are various approaches. The leader can appoint people to be responsible for each task. Volunteers may be called for, perhaps by creating a sign-up sheet. A mixed method is to assign someone to lead a task and then have people volunteer to work on the task.

A more sophisticated version of the sign-up sheet is to identify the kinds of people who ought to be involved in a particular task. You can then ask people to volunteer for tasks based on the slots available.

Having identified the what and the who, it is critical that you review the decisions reached and make sure that everyone understands what has been decided and who is going to do what.

Attend to the End: Pay as Much Attention to Endings as You Do to Beginnings. Does this sound obvious? Not necessarily. Recently Dick took some lessons in public speaking. At one point, the instructor asked him how he closed his speeches. “I usually end with a question-and-answer session,” he replied.

“Absolutely the wrong way to end a speech,” the instructor told him. “As the questions and answers gradually peter out, you fade to nothingness. The impact of your speech fades with it.”

If you don’t want your meetings to end on a whimper, you need to put as much thought and attention into saying goodbye as you did to saying hello.

76

In our work, we like to end by taking time to review decisions and agreements so that everyone is sure what has been decided and what are the next steps. Then we reflect together on the work that has been accomplished. We ask people to identify what they appreciated about working with others. What helped the work go smoothly? What inspired creativity? Which moments were fun? Sometimes we celebrate our work together with food and drink. We don’t rush the ending nor do we drag it out.

Everyone leaves meetings with thoughts about how they could be improved. Why not bring those conversations into your meeting so that you can improve the way you work together? If you end your meetings by asking those present, “What did we do well today and what do we need to do differently next time we meet?” we guarantee that your meetings will improve.

Special Considerations

Large meetings and meetings that extend for more than an hour offer the opportunity to work with groups of various sizes. People sometimes need to work alone, sometimes in pairs, sometimes in small groups, and sometimes in larger groups. Solitude gives people a chance to think things through. Writing or taking a walk are good ways to provide this time for reflection. Working in pairs or trios provides a safe space for people to share ideas. In groups of two or three, people get to know each other in a way that they are not able to do in a larger group. We use large meetings when we want to build a critical mass for change, small groups when we want to develop the details.

Use mixed groups and homogeneous groups as needed. Mixed groups include people with different views or from different parts of the organization. They are important when you want to create innovative solutions or to examine the whole from a variety of viewpoints. Homogeneous groups consist of people with the same point of view. They are valuable when you want to tap into a particular viewpoint. For example, you might have all the supervisors meet together to prepare a report reflecting their perspective on an issue.

77

Meetings as Rituals

Meetings are stylized rites for coming together. It is in the meeting that the whole system by its behavior demonstrates what’s important. Shaking hands, having coffee and donuts, passing out prepared materials for those present, getting the “word” from the leadership, and arranging participants’ seating are examples of common meeting rituals.

Long rectangular tables provide structure to a ritualistic way of gathering that emphasizes authoritarian behavior while circular tables emphasize an egalitarian spirit. Handshakes prior to the meeting represent perfunctory connections between people, while taking time to discuss what you have to do or say to be fully present at this meeting allows for deeper connections. Meeting processes that support people discovering what they know naturally and building their future together are powerful involving mechanisms, while being told what to do dampens people’s energy.

Over time meeting processes become ritualized. They become the way things are done around here. Recently Dick was in a meeting where the leadership team was discussing an important direction for the company. At one point in the meeting, one of the members said, “I’m not sure why we are discussing whether to adopt this plan; we all know Tom (the CEO) is going ahead with the plan.” This group’s meeting ritual was that the leader presented a course of action to which he was already committed, the group discussed it for a while, and then when the leader felt he had heard from everybody, he announced his decision, which rarely deviated from his original plan. The group had developed a pseudo-involvement ritual. They went through the motions of involvement while at the same time everyone in the room knew that their voice did not count.

In another organization, the value of connection has become so important that people would not think of beginning their meeting without taking time to welcome newcomers and connect with each other prior to doing the business portion of the meeting. Participants so valued these activities that they have become “ritualized” portions of their meetings.

Rituals help us make meaning of what is going on and build bonds among those present. Some meeting rituals emphasize authoritarian behavior; others emphasize an egalitarian spirit. Most meeting rituals go unnoticed; they are just the way we do things around here. Examining the meaning behind our rituals allows us to uncover hidden messages that may be working for or against the change you are trying to create. When you look for the involvement edge at each stage of the meeting, you create new rituals that add meaning to what you are doing.

78

Meetings That Generate Involvement

When it comes to meetings, people are constantly making choices. They choose whether and when to show up and whether and when to leave. They choose how much energy they will put forth. They choose to speak up or remain silent. When you understand the power of choice, you conduct your meetings differently. Meetings are rituals that convey powerful messages about how people are going to be involved. Examining our current meeting rituals gives insight into the hidden message behind our actions. Designing meetings using the meeting canoe helps create new rituals that give your meetings the involvement edge.

Is it possible to have a meeting without using the process we’ve just described? Can you hold gatherings without welcoming people, building connections, building a shared understanding of the way things are, crafting a picture of where you want to go, deciding who does what, and saying goodbye? Of course. But will these gatherings generate the kind of involvement that gets things done? We doubt it.

Chapter Checklist

Here is how you create high-involvement meetings:

- Start by making people feel welcome.

- Take time to foster connections among people.

- Discover the way things are—build a shared picture of the current situation.

- Elicit people’s dreams—build a shared picture of where you want to go.

- Decide on who does what to create the future you’ve agreed upon.

- Pay as much attention to endings as you do to beginnings.