CHAPTER 1

looking into your BRAIN'S TOOLBOX

APPLE BLOSSOMS

![]() Sanguine Conté on acid-free foamcore board

Sanguine Conté on acid-free foamcore board ![]() 12″ × 15″ (30cm × 38cm)

12″ × 15″ (30cm × 38cm)

Drawing is fun! Why, then, does drawing seem to be so difficult for most people, even art students? Why should it be? All the information is right in front of you. It's like taking a test with all the answers on the board. Yet for some reason, you struggle to transfer that information to your paper. Drawing shouldn't be a frustrating process for anyone. Let's find out why it so often is.

Like most people, I used to think that learning to draw was simply a matter of developing drawing skills. This is only partly true. Developing these skills requires you to know your problems, and know them well. This chapter will do just that by explaining the sources of the most common problems you will encounter in drawing. You've probably already encountered these problems and considered them as evidence of inability. This is simply not true!

Everyone who attempts drawing must, in one way or another, overcome the problems discussed in this chapter. It may be easier for some more than others. When I was learning, I was in the middle. It wasn't easy, but it was easy enough that I was encouraged to work hard and keep practicing. Knowing what causes your problems will make it easier to overcome them, and you need look no further for the source of these problems than inside your brain.

If you're frustrated with drawing, it's because you're using the wrong mental tools for the job. Can you see what you want to draw, but when you try to draw what you see, it comes out wrong? Let's discover what your own brain is doing wrong and why.

The two information-processing tools of your brain

Your brain processes visual information entering through your eyes in two distinctly different ways: spatially (or visually), and intellectually. The first and faster is the spatial process. Its primary function is to keep you informed about the constantly changing space around you by recording where and how big things are. It perceives shapes and spaces, dark and light patterns, vertical and horizontal orientation, size relationships and the relative locations of shapes.

The spatial part of your brain does not identify these as trees, cars and people; that kind of identification comes later. All of this is done on autopilot, just at the threshold of your consciousness. When you parallel park a car or walk through a crowded mall, you use this spatial tool. Its primary job is to navigate you through space safely.

The analytical or intellectual portion of the brain processes the spatial information not as visual images, but as data. When you identify the shapes you are seeing as trees, cars, people and so on, you are using the intellectual brain. This is the right tool for just about every other conscious activity of your life. But when you use this part of your brain to draw, the results are disastrous. It first translates the visual information it has received from the spatial brain into data, then creates a simplified visual symbol to stand for the information.

How Your Brain Processes What It Sees

Complex shapes enter the brain through the eyes and are simplified by your intellectual brain into symbols that merely represent the original item. These symbols are recalled when you try to paint what you see. Additional information about these things is added to the perceived information. As a result, you may paint a person, animal or object as you think it should look instead of how it actually appears.

How your intellectual brain interferes

There are four ways in which the intellectual brain distorts information needed for drawing, thus causing the most common problems.

-

It interjects previously stored data about the object into the activity of drawing.

-

It calls up early symbols created to stand for (not look like) the complex visual information it receives.

-

It creates new symbols and generalizes information to make it easier to store.

-

It focuses on surface details for which it has a name and ignores information that explains the structure of forms.

FROM THE ARTIST'S BRAIN

Drawing problems arise when we attempt to do the job with the wrong tool.

POLPERRO HARBOR

![]() Graphite pencil on bristol board

Graphite pencil on bristol board ![]() 9″ × 10½″ (23cm × 27cm)

9″ × 10½″ (23cm × 27cm)

PROBLEM 1 The intellectual brain imposes previously stored data into the drawing.

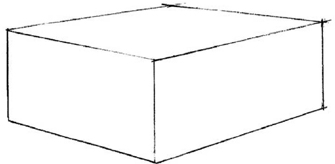

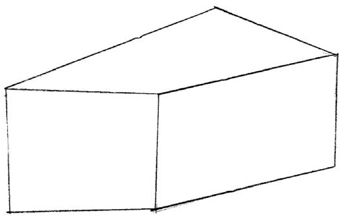

This problem is evident when you start to draw a simple object like a box. The conflict between what you know (analytical, intellectual) and what you see (visual, spatial) is very clear.

You want to draw the box, but you're faced with a dilemma: The visual information does not match the intellectual information. Is the object made up of rectangles or of these odd geometric shapes perceived by the visual brain?

The Dilemma

Does trying to resolve the conflict between visual and intellectual processing make you feel like this?

Perspective Is Not the Problem

Most people complain that they don't understand perspective and that this lack of knowledge makes it difficult to draw a simple box. It is not lack of knowledge that causes the problem.

What's Really There

These are the shapes the visual brain records. It sees an object with three planes, each having a different shape. And not one of these shapes has a 90-degree angle!

What Your Smarts Say

Your intellectual brain says, “Oh yes, that is a box. I can see three of its planes.” And what does it know about those planes? It knows that the planes are composed of rectangles, four-sided geometric shapes with four right angles, especially with adjacent sides of unequal length.

The Answer

Both sets of information are true! One is a visual truth about the shapes as they are seen, and the other is an intellectual truth about what the shapes mean. If you want to build a similar box, measure it and use the intellectual data. If you want to draw it, ignore that data and focus on the shapes you see.

However, since the analytical part of your brain controls the conscious activities of your life, it naturally thinks it should also control the act of drawing. And this is the cause of the problem. You are trying to draw the box, but your brain is sending two conflicting messages. What do you do? Compromise?

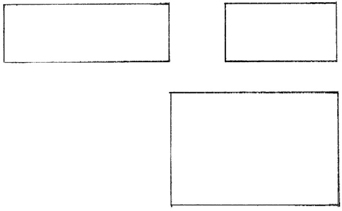

Is Compromise Possible?

We're civilized people, can we meet halfway between true visual information and intellectual truth?

The Sad Truth

Compromises in drawing do not work. This is the kind commonly reached; it contains elements from both bodies of information.

Your intellectual brain compromises by admitting that the angles you see are not the 90-degree angles it knows are there, but it is unwilling to find out exactly what they really are. It tells your hand to put in any angle that is somewhat close. Your task in drawing is to turn off the analytical information and focus only on the visual.

FROM THE ARTIST'S BRAIN

For most people, drawing is a fight with the intellectual brain to adjust the drawing bit by bit toward the visual truth of what they see.

Problem 1 in Action

A container with a round opening presents another example of this classic conflict between the visual information supplied by the eyes and the analytical data supplied by your intellectual brain.

I know this mistake is the result of a compromise and not an error of perception: In thirty years of teaching, I've never seen a student observe a narrow elliptical opening and draw an even narrower ellipse. Invariably, students draw the opening wider than they see it. If it were only a mistake in observation, some students would draw a too-narrow version of the shape. This was my first clue that something happened to the observed information after it entered the student's brain, distorting it on a consistent basis.

I find that making you aware of the mental conflicts you will encounter makes you look twice before putting pencil to paper. And that second look gives you the information you need in order to draw it right the first time. As a result, you're able to draw faster and more accurately.

Not Just Boxes

Do you have problems drawing simple containers like this one?

Seeing vs. Knowing

What we see of any circular opening is a foreshortened view, an elliptical shape. We know it is a circular opening, and we know what a circle looks like.

Why We Can't Just Get Along

This is what the compromise drawing might look like.

PROBLEM 2 The intellectual brain creates symbols intended to stand for (not look like) the visual information before you.

We create symbols for everything. It is a method for compressing large amounts of information into smaller packages. The digit “5” is a symbol for a given quantity. The Yin-Yang symbol stands for a complex cultural concept.

The brain also creates symbols for the things we see, acting as shorthand versions. They are not meant to be a likeness of the item. For example, the common symbol for mountains -^^^- is not meant to resemble a particular mountain, but to stand for all mountains.

For a child, creating symbols is a method of communicating feelings. You will find that children spend much more time creating symbols on blank paper than they will spend with coloring books. The paper gives them a world in which to express themselves. At some point, most people become dissatisfied with these symbols and try to shift towards making their creations appear more like the individual items they see. We call these people artists.

Most people encounter difficulties and give up. For them, the intellectual brain (which has received all the attention in school and at home) is dominant.

Drawing is based entirely on the visual information supplied by the visual brain. Drawings are the product of intense observation, not intellectual interpretation.

The Symbols We Make

Art That Stands for Something

No child thinks this is how Mommy really looks. In fact, when asked they say, “This is Mommy,” not, “This is what Mommy looks like.”

Building Your Symbol Collection

Between the ages of three and ten we create a host of symbols to represent the things around us. These symbols become more complex as we age, and new symbols are created for all the details.

Problem 2 in Action

I often see people who are looking directly at a pine tree draw a version of their childhood pine-tree symbol. How does this happen?

The intellectual brain is trying to control the drawing process. It recalls the childhood symbol, and it compromises by changing the symbol a little. Intense observation would reveal information about the tree's shape and edges, but this not only takes time, it also puts you in a visual mode that shuts the intellectual brain out. Ouch!

A person sees something like this.

The intellectual brain recalls a childhood symbol for “pine tree.”

Seeing this symbol work as well as it did in the third grade, a compromise is reached in which some of the observed features are grafted onto the childhood symbol to create a new symbol.

From Seeing to Remembering

The image in front of a person goes through a transformation from what is seen to what is remembered, resulting in a disastrous compromise.

PROBLEM 3 The intellectual brain creates new symbols and generalizes for better storage and retrieval.

Accurate drawing requires intense observation. You can assume nothing about the object: Approach with a blank page and the willingness to see it as it really is. That is far different than simplifying and generalizing the information for easy storage. The two tasks are simply not compatible.

There is nothing wrong with the generalizing mode of the intellectual brain. It protects us from sensory overload. We can't go through each day taking note of every little detail. We would soon burn out. So we create broad generalities that do not bother with the specific variations. Roses are red. Bananas are yellow.

Symbol-making is one way of simplifying and generalizing visual information. However, when it insinuates its symbols into the drawing process, a process that requires the recording of specific, unique information, it becomes a problem.

The Beginnings of a New Symbol

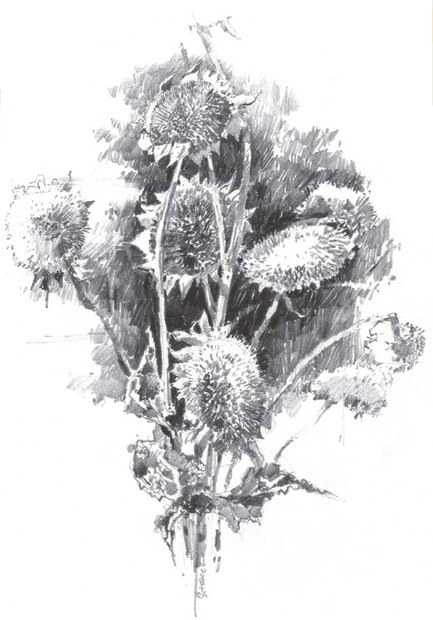

When you look at these dried sunflowers, you identify them, store the information in case you have to identify them again, and move on. If asked about their color, they are brown and dark. Period!

However, if I tell you to draw them, your response might be different. “What? That's too difficult! They're too complex!” To help you, the intellectual brain will create some new symbols to simplify the task. Not so good of a friend!

What Your Intellectual Brain Creates

This symbol represents the essential information concerning the dried sunflowers without intense observation. It records the generally prickly nature, the curve of the stems and the fact that there are larger, triangle-shaped objects around their perimeter. This drawing doesn't even mention the leaves. It seeks general information that can stand for all dried sunflowers.

Typically, the intellectual brain does not care about the relationship of each flower to the next one or about the peculiar twist in the dried petals or the specific curve of each stem. It simply asks, “Where are they?” and answers, “At the end of curved stems.” It seeks a symbol for all petals. Likewise, it creates a symbol to stand for all the prickly centers and selects one curved stem to stand for all stems.

Problem 3 in Action

Doing a drawing that actually looks like these sunflowers will require you to create marks that convey the actual quality of the sunflowers, and that you place all the parts in the same spatial relationships that exist in the original forms.

Don't fall into the trap of letting the intellectual brain give you the “Tarzan approach” to your drawing. “Me Tarzan, you Jane!” “Sky blue!” “Grass green!” “Sunflower prickly!” “Stems curved!” You can do a faithful drawing of these sunflowers only if you turn off the symbol-making analytical brain and allow your more artistic, visual brain to handle the job. Your visual brain enjoys the complexities of the image.

SUNFLOWERS

![]() Graphite pencil on bristol paper

Graphite pencil on bristol paper ![]() 9″ × 7″ (23cm × 18cm)

9″ × 7″ (23cm × 18cm)

Drawing as a Means of Discovery

This drawing discovers the complexities of the forms, the brittleness of the leaves, the prickly quality of the centers, and the lights and darks as they reveal an edge in some places and dissolve it in others. Unlike the intellectual symbols, this drawing cannot be repeated. Another drawing of the same subject would yield a different result. Even a slightly different view would produce a completely new set of relationships to explore.

PROBLEM 4 The intellectual brain focuses on the surface details it can identify, ignoring information that explains the form.

A common statement by adults who claim not to be able to draw is, “I can't even draw stick figures.” That, of course, is not true. What they mean is, “I can't make my stick figures look realistic.” Well, of course they can't — people don't look like stick figures!

It's odd that in our culture we assume that everyone can (and should) learn basic language skills although only a small percentage will become authors. We also assume that everyone can learn math while only a few will become mathematicians. However, we assume that drawing requires some special talent possessed by only a few and the rest need not try.

When I first started teaching drawing, I had no idea where these symbol images came from. Students looked at a subject right in front of them, but their drawings seemed to come from another world. And in a sense, they were. The subject for the drawing was in the visual world, but the symbol that materialized on the paper came from a world of data storage. Drawing ability was overshadowed by conscious symbol-making. Discovering your hidden talent doesn't have to take years.

Drawing well requires you to reject the symbol proposed by your intellectual brain and ask yourself, “What do I actually see?” There are no shortcuts. The information cannot be generalized or memorized. It must be savored and enjoyed.

Like a good meal, an honest search for visual information in a subject is enjoyable and satisfying. Only your intellectual brain thinks it's tedious.

Photo Reference

This gentleman in England was kind enough to allow me to photograph him for a drawing.

The Symbol Drawing

This is a typical symbol approach to drawing a head. Notice the attention placed on nameable details like glasses, lips and hair. But it pays no attention to their shapes. Glasses are glasses; why bother to get the actual shape when a symbol will do? The intellectual brain does not notice the hair is dark (in shadow) on one side and white on the other. Also, the intellectual brain doesn't care about the actual tilt of the head, but includes details such as eyelashes although it can't see them. It only knows they are there.

Beginning to See

This, on the other hand, is the beginning of a real search for observational details. Notice the sighting lines that explore the vertical and horizontal relationship of the hairline to the glasses, the eyebrow to the ear.

This kind of search produces a likeness. The search narrows until it includes the small angles of the shadows around the eyes, the spots of light on the glasses' rims, and so on.

An Almost Completed Search

Here the search has progressed to a more complete stage. I would finish this drawing by pushing the values (the lights and darks) and deciding what I wanted to emphasize about him.

POINTS TO REMEMBER

![]() Your intellectual brain can't draw — it sacrifices all the wonderful information that makes beautiful drawings. It interjects, symbolizes, generalizes and focuses on details. Work around it to see only shapes.

Your intellectual brain can't draw — it sacrifices all the wonderful information that makes beautiful drawings. It interjects, symbolizes, generalizes and focuses on details. Work around it to see only shapes.

![]() Pay attention to shadows. When the symbol creation of your intellectual brain is unsatisfactory, it tries to remedy the problem by adding details. Its theory is that if there is a problem, more details will solve it. Of course, it focuses on the details for which it has names: eyelashes, stains, bumps, holes, scratches, etc. It will ignore shadows that explain how the form turns in space.

Pay attention to shadows. When the symbol creation of your intellectual brain is unsatisfactory, it tries to remedy the problem by adding details. Its theory is that if there is a problem, more details will solve it. Of course, it focuses on the details for which it has names: eyelashes, stains, bumps, holes, scratches, etc. It will ignore shadows that explain how the form turns in space.

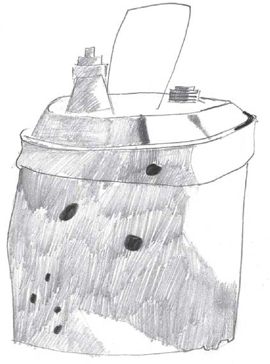

Problem 4 in Action

This old gas can is a good example of different kinds of detail. It has decorative details that may enhance the visual interest of the piece but do not explain its form. But, it does have structural details that help us understand its form, structure and three-dimensionality. Can you see the difference?

What Makes the Shape?

Ignoring Form and Latching Onto Details

Look familiar? This is a typical beginner's response to drawing and shading the can. You can tell the intellectual brain controlled the process. Notice the proportions: It's too wide for its height; the spout and lid are too small and too far apart. The bottom is not fully rounded, and the shadowed area is not dark enough. These characteristics were ignored by the intellectual brain as it jumped into the drawing and headed right for the bullet holes.

Check out those dark bullet holes! You can't help but notice them, can you? Why are they so pronounced? It's because the intellectual brain could identify them and put a name to them. You can almost hear it say, “Hey, bullet holes! I can draw those. They're just black dots. That's easy!” It doesn't notice that the holes are only a little darker than the shadowed can.

Drawing Like It Is

In this drawing, I have rendered the shadow almost as dark as the bullet holes. This is the correct value relationship. I have also drawn the height to width and other size relationships correctly. I checked the angles and the positional relationships of the handle, the spout and the lid. A visual likeness is created by these relationships, not by the accumulation of details.