10. Insurance and Your Credit Score

Tawny had been a loyal Allstate customer for 15 years. The Texas woman had paid her premiums on time and had never gotten a ticket, had an accident, or filed a claim.

Then her auto insurance premium tripled:

“I went through a devastating divorce where I lost my home and credit,” said Tawny, who became a single mother with three small children. “About a year later, I got a notice from Allstate that my auto insurance rate was increasing.... I wasn’t too worried until I got my first bill. I went from paying $396 every six months to $1,200.”

Kyra in Bridgeport, Connecticut, never had trouble with her auto insurer. But when she tried applying for a renter’s insurance policy with MetLife, she was denied:

“Although I have some previous credit problems, I would have never guessed in a million years that I would be denied a $200-per-year renter’s insurance policy based on my credit history,” Kyra steamed. “I’m self-employed, educated, and a productive citizen. I’m not any more likely to file an insurance claim than an unemployed individual with a high credit score.”

Glen in El Paso got a notice that his auto premium was being raised to $125 a month, from $85. After getting the runaround from his insurer, he discovered the reason wasn’t bad credit—it was too much credit:

“My wife had opened a GAP department store credit card with a $500 limit, and used it,” Glen said. “Nothing more.”

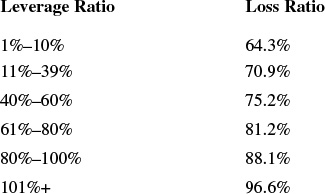

Glen was told by his insurer that consumers who use more than half their available credit on a department store card “are considered high risk and therefore must pay higher rates.”

John in Negley, Ohio, was recently notified that his homeowner’s insurance premium would soar because of a recently filed bankruptcy. His only question for me: “Is this legal?”

That’s typically one of the first questions many people have when informed that an insurer has raised their rates or denied them coverage based on their credit.

Here’s the other question they understandably raise: What does my credit have to do with anything when it comes to insurance?

“My circumstances forced me into bankruptcy.... I’ve never had an accident in my life,” said Chestena in Texas, who a year after her bankruptcy was quoted auto rates that were $400 to $2,000 higher than what she paid before she filed. “Poor credit does not mean that you are a risk or that you are prone to accidents.”

Insurers, though, think otherwise. They believe credit is an excellent predictor of whether you’ll file a claim—better, in fact, than almost any other factor, including your previous driving history.

What’s more, using credit for insurance decisions is not only legal in most states, it’s also the norm. The vast majority of property casualty insurers—those who provide auto and homeowners policies—use credit-based insurance scores in their underwriting.

Insurance scoring was slower to take hold in Canada, but by 2010, more than half of Canadian insurers used the scores.

The way insurers use credit information, however, can differ markedly from the way lenders use the same data. That’s why some people who have good credit scores and would qualify for the best rates and terms from most lenders still wind up paying higher premiums.

History of Using Credit Scores to Price Insurance Premiums

Insurers have actually been using credit information since at least 1970, when the Fair Credit Reporting Act first sanctioned the practice. Lamont Boyd, who became a Fair Isaac executive, remembers his days reviewing credit reports as a young insurance underwriter in the 1970s.

Boyd says his job was to look for “clearly ‘bad’ signals,” such as bankruptcies, foreclosures, or collections, which would be used as a reason to turn down the customer who was applying for insurance.

The process, according to Boyd and Fair Isaac, was subjective and inconsistent—much like the human-powered lending decisions being made in much of the credit industry at the time. People who might have been good risks, despite a few blemishes, were being turned down, whereas those who might have been worse risks were being accepted.

Fair Isaac decided to tackle the insurance market in the late 1980s, shortly after introducing the first credit scores based on credit bureau information. Although the company doesn’t dominate insurance scoring the way that it does credit scoring, Fair Isaac has been instrumental in promoting the idea that credit information can give insurers an edge in predicting losses.

Fair Isaac introduced its first credit-based insurance score in 1991, and it hired actuarial consultants Tillinghast-Towers Perrin to review Fair Isaac’s in-house studies of the links between credit history and insurance losses.

The correlations were so strong, said Tillinghast principal Wayne Holdredge, that the consultants were suspicious:

“We went back to the companies [that supplied the insurance data] and made them sign affidavits, saying that they hadn’t cooked the books,” Holdredge remembered. “Now the correlation is well understood, but back then it wasn’t.”

The cause of credit-based insurance scoring got another boost in 2000, when MetLife actuary James E. Monaghan published a study that matched 170,000 auto policies to the credit histories of the drivers.

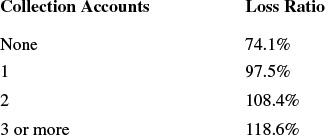

Over and over, Monaghan found a correlation between black marks on credit reports and higher loss ratios for insurers. (A loss ratio measures how much an insurer pays out in claims for each dollar collected in premiums.)

Loss ratios rose steeply, for example, with the number of collection accounts appearing on a driver’s record. Those who had no collection accounts cost the insurers an average of 74.1 cents for each dollar collected. Drivers who had one collection account had 97.5 cents in claims for each premium dollar collected, whereas those who had three or more collections cost insurers about $1.19.

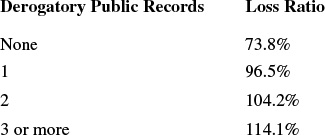

Monaghan found similar patterns with derogatory public records such as bankruptcies, liens, repossessions, foreclosures...

...with delinquencies...

...and with debt utilization, or how much of available credit was in use...

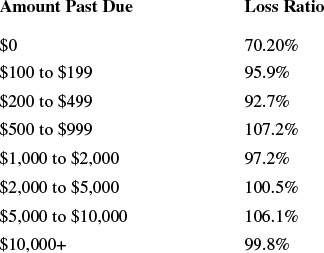

Correlations were a bit less linear for other credit information, such as inquiries, age of the consumer’s oldest account, and amounts past due...

...but the links were still strong enough to suggest a definite relationship between how well people handled their credit and how much they cost their insurers.

Monaghan’s status as an industry insider, of course, led many consumer advocates to question his results. An independent study by the University of Texas at Austin a few years later, however, found similar patterns and a “statistically significant” link between credit scores and auto losses.

The UTA researchers matched credit scores to 153,326 auto policies issued in early 1998 and tracked which policies made claims in the ensuing 12 months:

“The lower a named insured’s credit score, the higher the probability that the insured will incur losses on an automobile insurance policy,” the UTA researchers said, “and the higher the expected loss on the policy.”

The average loss per policy during the period was $695, but drivers who had the lowest credit scores cost their insurers $918, whereas those with the highest scores cost $558.

An even larger study of two million auto and homeowner’s policies was conducted by the Texas Department of Insurance. That study found a similar strong link between credit scores and claims.

But What’s the Connection?

What none of the studies have proven is a causal link between credit and claims. In other words, they can’t explain why poor credit should lead to more insurance losses.

Insurers speculate that people who are responsible with their credit might be more likely to be responsible with their cars and homes. Or perhaps people who mismanage their finances are more likely to make claims because they need the cash.

MetLife’s Monaghan, like others in the insurance industry, believes no one will ever say for certain why the two are linked. He points out that it’s impossible to prove a causal link for most factors used in insurance decisions.

The fact that you’ve been in an accident in the past, for example, doesn’t cause you to have another accident. But most people can accept the idea that someone who has already had an accident or two might be more likely to have another one. It makes sense, in a way that using credit history for insurance does not.

The lack of a clear, logical link isn’t the only thing that concerns consumer advocates about insurance scoring. Among the leading critics of insurance scoring is Birny Birnbaum, a former Texas insurance commissioner who believes insurance scoring might be illegally discriminating against low-income people and minorities.

Birnbaum doesn’t believe the UTA study was rigorous enough to determine whether it’s really credit, rather than some other factor, that correlates with insurer losses. He fears credit is actually some kind of proxy for a factor that insurers wouldn’t otherwise be allowed to use, such as ethnic background or income.

In fact, the Texas insurance department study found that black, Hispanics, and lower-income populations had worse-than-average credit scores, which meant they were getting worse-than-average rates from many insurers, regardless of their claims history, driving record, or other factors.

Insurers insist that their use of credit scoring is actuarially sound and not discriminatory. Persistent concerns about fairness, though, have led a few states to ban credit scoring by insurers, whereas others have imposed restrictions on how insurance companies can use credit information. Several states have adopted model legislation crafted by the National Conference of Insurance Legislators to regulate and restrict the use of credit. Among other things, the model legislation does the following:

• Forbids insurers from using credit information to deny, cancel, or fail to renew a policy

• Prevents insurers from using a consumer’s lack of a credit history as a factor in determining premiums or coverage

• Requires insurers to review their credit-related decisions within 30 days if it turns out those decisions were based on erroneous credit reports

Critics say the legislation does more to legitimize insurance scoring than protect consumers, but others say the laws at least provide insurers with some curbs.

Consumers already had some protections, theoretically, under the Fair Credit Reporting Act. The act requires insurers to notify consumers if credit information has affected a policy decision in any way, and include the following in the notification:

• The reasons for the insurer’s decision

• The bureau from which the credit information was obtained

• Instructions on how the consumer can get a credit report

If my mailbag is any indication, some insurers aren’t doing a good job of following the law.

Glen, the man in El Paso whose insurance increased because of his wife’s GAP card, played a long game of cat-and-mouse with his insurer when he asked why his rates had been hiked:

“My insurance agent passed me to corporate [headquarters]. Corporate threw up their hands and claimed it wasn’t their fault, it’s how [the company’s score provider] scores my credit. I ask, how do they score it? They replied that I could only get this information from [the score provider],” Glen recounted in an email.

“[The score provider] won’t answer the phone. You have to write in. I did. [The score provider’s] answer was, ‘It must be your credit report or your driving record.’ I got both. Driving record perfect. Credit report even better than when I first got insurance.

“Finally [I] get a number to call. [The score provider said it] scores your credit according to how the insurance company wants them to. The insurance company then says they can’t discuss the criteria [because] it’s proprietary.”

Glen said he finally pressured “someone at my insurance company to pressure someone at [the score provider] for an answer,” which is when he learned that a maxed-out department store card was the culprit.

Clearly, it shouldn’t be that hard to get answers.

Other readers have told me they called insurers for quotes, only to later find an inquiry by the insurance company on their credit reports. They say they weren’t told a credit check would be run or given an explanation of how the information might affect their premium.

Even fans of insurance scoring admit that insurers sometimes fumble the ball. Boyd, Fair Isaac’s point man on insurance scoring, agrees that many insurers aren’t adequately explaining what they’re doing. Customers are left baffled, as are the insurance agents who have the most contact with clients:

“The insurance companies have not done a good job educating their front-line agents to explain what’s happening [to their customers],” Boyd said.

Adding to the confusion is a market that’s even more splintered than the credit-scoring market. Fair Isaac sells its model to more than 300 insurers, but the biggest companies either have their own custom insurance scores or use the LexisNexis Attract score.

Many people who have good credit scores, for example, have been told by their insurers that their rates increased because of their attempts to get credit.

If the insurer were using Fair Isaac’s score, too many inquiries might at worst cause the customer to miss out on the insurer’s best discounts, Boyd said. The consumer would still enjoy a break on premiums because of good credit, he said—it just might not be the best discount available.

If the insurer were raising everyone’s rates by 15 percent, a customer who had a few too many inquiries might be charged 10 percent more, whereas the insurer’s highest-rated customers might pay 5 percent more—and its worst-rated customers 20 percent more.

But Boyd couldn’t vouch for how an insurer’s custom score might treat inquiries, and the insurers who use custom scoring say such details are proprietary information.

Furthermore, you don’t have a right to see the score that’s being used to judge you, as you often do with credit decisions. You’ve long had a right to see the scores used in mortgage lending decisions; starting in July 2010, lenders have been required to reveal the scores they use when you don’t get the best rates and terms. Insurers, however, aren’t required to fess up.

Insurers are doing themselves no service by failing to explain the rules to their customers—particularly those who have good credit. As Boyd notes, someone who has bad credit might just accept a high premium as fate, but someone who has good credit is likely to react badly, even if they’re just being shut out of the insurer’s top tier of customers:

“Instead of getting an A, they got an A–,” Boyd said, “and they’re the ones who are going to start asking questions.”

Insurers insist that credit-based scoring helps more people than it hurts. They say responsible policyholders pay less for their coverage than those who are more likely (in the insurers’ view) to file a claim.

Indeed, some of the people who have written to me about their insurance scoring experience had happy news:

“I’ve been working hard on paying down debt and just bought a house this year,” wrote Christopher of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. “About four months ago, I got my new insurance premium bill in the mail and noticed that it was significantly cheaper than what I was paying before. Nothing had changed but my credit rating.... This was confirmed by my State Farm agent. [Insurance scoring] is a good thing.”

What Goes into an Insurance Score

It’s hard to be definitive about what does and doesn’t affect your insurance score. Many big insurers have their own credit-based scoring models, and they’re not talking much about how those work. Fair Isaac is talking some, but its formula doesn’t dominate the insurance-scoring world the way its credit score does the lending world.

But some information is better than nothing, and Fair Isaac is willing to share some of the details of what goes into its insurance-scoring model. The factors used are similar to the ones considered with credit scoring, although their weight can vary:

• Forty percent of the average insurance score is determined by payment history—whether you’ve paid your bills on time. That compares to 35 percent for the credit-scoring model. As with credit scoring, the model looks at your payment history on different types of accounts, including credit cards and installment loans. Black marks such as delinquencies, charge-offs, collections, foreclosures, repossessions, liens, and judgments can seriously affect your score.

• Thirty percent of your insurance score is based on your credit utilization, which is roughly the same percentage that your credit score uses. The score factors in the amount you owe on all of your accounts and how that compares to your credit limit (in the case of a credit card) or the amount you originally borrowed (for an installment loan).

• Fifteen percent of an insurance score has to do with the types of new credit you’ve been granted recently—how many new accounts you have, how long it’s been since you opened a new account, and the number and type of inquiries on your report. By contrast, about 10 percent of the credit-scoring model is derived from the number and types of new credit you’ve acquired.

• Ten percent of the insurance score is based on the length of time you’ve had credit—which counts for about 15 percent of your credit score. Both scores factor in the age of your oldest account and the average age of all your accounts.

• Five percent of your insurance score measures types of credit in use, compared to 10 percent of your credit score. Once again, Fair Isaac is looking for that “healthy mix” of different types of credit, without providing much guidance about how many of each type of account you should have.

As you can see, Fair Isaac’s insurance-scoring model puts slightly more emphasis on your payment history and your recent behavior in applying for new credit. The age of accounts and their mix are slightly less important.

Keeping a Lid on Your Insurance Costs

The strategies you’re learning in this book will help you improve and protect your credit, which should, in turn, help you to qualify for lower insurance rates in most states.

Good credit alone, however, isn’t enough to keep you from overpaying for insurance. You need to be smart about the kinds of coverage you buy and how you use that coverage.

Whether your credit is good or bad, consider the steps outlined in the next sections to control your insurance costs.

Start Thinking Differently About Insurance

Many people feel somehow ripped off if they pay their premiums for years without ever making a claim. But this is exactly what you want to happen.

Insurance is meant to protect you against the kind of big expenses that could wipe you out financially—not to pay for the little stuff you could easily cover out of your own pocket.

So if you’re using insurance properly and you never make a claim, that means you’ve never suffered a major catastrophe. Who among us wouldn’t like to get through life without having a car totaled, a house burn down, or a lawsuit filed against us?

People who don’t understand the role of insurance often try to shift as much risk as possible to their insurer—by choosing low deductibles, for example, or making claims for every little ding their cars suffer in supermarket parking lots. That’s a quick road to higher premiums.

In fact, making a lot of claims—or making even one of the wrong kind of claim, as you’ll see later—can make it difficult for you to get coverage at all. Insurers share claims information and are on the lookout for people who are likely to cost them money. People who constantly turn to insurers to pay for damage they could have covered themselves often find fewer and fewer companies willing to insure them, and those companies are charging more and more to do so.

Does this seem unfair? If you think it does, you would expect to get some support from J. Robert Hunter, a consumer advocate and insurance expert for the Consumer Federation of America. He’s been sharply critical of the insurance industry on many occasions, and he’s seen by many reporters as the “go-to guy” when they need a succinct quote damning some bit of insurer foul play against consumers.

But Hunter, an insurance actuary and former Texas insurance commissioner, also knows how insurance is supposed to work. He maintains high deductibles on all his personal insurance policies, and he urges others to do so, too. He sets aside the money he saves on premiums to pay for out-of-pocket expenses.

Rather than protest, realize that this is how the insurance game is meant to be played. Preserve your coverage for the big disasters, and you’ll save in the long run.

Raise Your Deductibles

This is one of the fastest and smartest ways to save money on insurance—but many people balk.

Raising your deductible means you’ll pay less every year in premiums. You’re also less likely to make claims for piddling stuff—claims that would likely result in your rates being jacked up.

So, if you can, boost your deductibles to at least $500 and preferably $1,000 or more. Leave at least that much money in your savings account to cover the cost of any accidents, and you’ll be money ahead in the long run.

Don’t Make Certain Kinds of Claims

There’s something else that insurance is not—and that’s a maintenance fund for your house and other property.

Insurance is designed to cover sudden and unexpected losses, such as a fire. If damage happens that you could have foreseen and prevented, you’re on the hook. Insurers expect you to inspect, maintain, and protect your property without their help.

So, if a storm tears shingles off your roof and the resulting leak ruins your dining room ceiling, your policy will probably pay for repairs. If your roof is just old and falling apart, though, you’ll have to reroof and fix the water stains on your own dime.

Termite and rodent infestations are another frequent cause of damage that few insurers cover. They figure you should have noticed the little critters and had them exterminated long before they had a chance to ravage your home.

If you make a claim for such problems, you very likely won’t get a dime. But the claim could still count against you when it’s time to renew your insurance.

Okay, let’s say that the damage is indeed “sudden and unexpected”: The rubber hose on your washing machine breaks and floods your house. Surely you should make that claim, right?

Maybe not. Insurers are particularly paranoid about water-damage claims. They took a beating from an exploding number of mold-related claims, including some famous ones, such as the contention from former Tonight show regular Ed McMahon that his home’s toxic mold killed his dog.

Insurers share their claims experience in a huge database called CLUE, for Comprehensive Loss Underwriters Exchange. Readers have told me that a single mention in the CLUE database is enough to blackball their home for years. Some say they didn’t even make an actual claim, but simply asked their insurer for information.

Tami of Seattle asked a claims adjuster to evaluate what looked like damage to her bathroom floor. The adjuster determined that water splashing over the tub had seeped under the vinyl flooring sometime in the past, but that there was no current indication of moisture and the damage was entirely cosmetic:

“This was enough to have my house branded as ‘water-damaged,’” Tami wrote. “When I tried to shop for a more reasonably priced homeowner’s policy, I was told by my agent that it was impossible because no one is accepting new policies with a history of water damage. None of the six companies they represent would accept my house. I was also told that even if I entirely replaced the bathroom floor, it would have no effect on my policy status.”

Oh, and it gets worse. A few readers have told me they had trouble selling their homes because of past water-related claims. Insurance companies balked at writing policies on the home for the new buyers; without insurance, mortgage lenders won’t approve a loan.

Is this entirely rational? Of course not. Insurers are overreacting, as they tend to do. Eventually, a few insurance companies will realize they’re avoiding some good customers, more will follow, and the water-related stigma will ease.

The best course for policyholders for right now, though, is prevention—and silence. Among the things you should be doing

• Regularly inspect your home. Every few months, check your roof and foundation for leaks or standing water.

• Fix any leaks immediately.

• Replace hoses on older washing machines and dishwashers. Your plumber can point you to a type that’s less likely to break.

• If you live in a cold climate, take steps to adequately insulate your pipes and prevent breakage.

If, despite your best efforts, you suffer water-related damage, seriously consider paying for repairs yourself if you possibly can, and avoid mentioning the incident to your insurer. Preventing the “water-damage” stigma from attaching to your home could leave you money ahead in the long run.

Be a Defensive Driver

A patrol officer once explained to me that there are few true “accidents” on the road, but many, many crashes.

What’s the difference? Accident implies the collision was out of the control of at least one of the drivers involved. That’s rarely the case. Although one driver might be the direct cause, many times the other drivers could have avoided the crash had they been driving more defensively.

Obviously, there are exceptions. One of my dear friends was killed when a tractor-trailer rig flew over a center divider and smashed into his car. There’s not much he could have done to avoid this accident other than staying home that particular day.

In most crashes, however, all the drivers involved are at least partially at fault. If you’ve ever been hit, you can probably think of ways you could have avoided the collision. Maybe you were tailgating or driving too fast, not giving yourself enough time and road space to react. Or maybe you just weren’t paying enough attention to what was going on ahead of you, or to the sides, or in your rear-view mirror. Who among us hasn’t been distracted in a car by a child, a conversation, a cell phone, or a music player?

Driving is dangerous business, and we owe it to ourselves, our passengers, and our pocketbooks to give it our full attention.

Use the Right Liability Limits

This might not save you money in the short run, but it could help you if you ever cause a serious accident or get sued.

Liability coverage pays for the damage you cause (or are accused of causing) to other people and other people’s property. If someone slips and falls in your house or suffers serious injuries in a car crash for which you’re found to be at fault, they can sue you for everything you’re worth—and then some.

That’s why you want to have liability coverage on your home and cars that’s at least equal to your net worth. Some insurance experts recommend having twice that amount, or even more for people who are “lawsuit targets”—doctors, lawyers, public figures.

If you need to buy more coverage than your insurer offers—liability coverage for autos and homes usually maxes out at $500,000—consider buying a separate “umbrella” or personal liability policy. These policies kick in after the liability limits on your auto or homeowner’s insurance have been exhausted, and typically cost about $300 for $1 million of coverage.

Drop Collision and Comprehensive on Older Cars

Collision coverage pays for the damage you do to your own car in an accident, whereas comprehensive covers the other disasters that can happen—your car is stolen, dented in a hailstorm, or squashed by a falling tree branch.

This coverage is usually a good idea on newer cars and is sometimes required by your financing company. The older your car, though, the less likely you are to get much money from the insurer even if the worst happens.

If your car is stolen or totaled, your insurance company will send you a check for an amount that’s usually somewhere between its trade-in value at a dealership and what it would be worth if you sold it yourself.

If you haven’t checked the value of your car lately, you might be surprised at how small that check is likely to be. (Online sites like Edmunds.com or KBB.com, the Kelley Blue Book site, can clue you in.)

If your car is old enough that you’d just replace it with a new one, and you wouldn’t have much trouble coming up with a down payment on that next car without your insurer’s help, dropping comprehensive and collision is a no-brainer. There’s something you need to know, however: If you don’t have comprehensive and collision on your car, you likely won’t have the coverage on a rental car, either. You might need to buy the rental company’s (notoriously expensive) coverage, or see if your credit card offers “primary” coverage that would include it. Most credit cards that have rental car insurance offer only secondary coverage, which means they pay only what your insurance company doesn’t. Some cards, including American Express, have optional coverage you can add to make the card your primary insurance. Call and ask your card issuer what’s available.

Shop Around

This has always been important, but never more so now that credit is such a factor.

Insurers tend to set their rates based on their own experiences. That’s why premiums for the same drivers and cars can vary by thousands of dollars from one insurance company to the next, even when credit isn’t considered.

If your credit is mediocre or poor, you’ll probably want to look for insurers that don’t use credit information. There are still a number of these companies out there; they believe they’ve found other good ways to manage their risk.

You can look for an independent insurance agent who can tell you which companies don’t use credit information, or simply call around and ask. Don’t give out identifying details, like your name and Social Security number, until you’re sure the company doesn’t use credit info. (Like others who have a “legitimate business need,” insurers are allowed to pull your credit reports without your permission. So if you don’t want them to check your credit, don’t give them the necessary details to do so.)

If your credit is decent, you shouldn’t shy away from companies that use insurance scores, because you could benefit.

A good place to start shopping is often your state Department of Insurance, which might offer some kind of premium survey that can help you see which companies are most likely to offer you a good deal, given your location and situation. (These regulators also might provide complaint surveys, so you can avoid the insurers that create the most problems for their customers.) An auto insurer that has a good track record of managing the risks of teenage drivers, for example, is likely to give you and your 16-year-old a better rate than one that wants to steer clear of underage drivers.

You can also use quote services such as InsWeb.com or call the companies directly.

You may wonder how shopping for insurance will affect your credit or insurance score. Insurers typically say their models disregard any inquiries related to insurance. Still, for security and privacy reasons, you want to limit how many entities are peeking into your credit files. Narrow down the field of potential companies before you give any insurer enough details to pull your reports.

Protect Your Score

Although insurance scores are a bigger mystery, much of the same behavior that protects your credit score should help improve and maintain your insurance score. Those behaviors include the following:

• Paying your bills on time

• Keeping balances low on credit cards and lines of credit

• Not applying for credit you don’t need

If you do need to open new accounts, try to do so after you’ve renewed your policies for the year.