3. VantageScore—A FICO Rival Emerges

I regularly hear from readers who thought they knew what their credit scores were—until they applied for a loan and found their lenders used dramatically different numbers. These readers are often astonished, and outraged, to learn that the credit scores they bought aren’t the ones lenders use. Consumer advocates complained that the “consumer education scores” sold by credit bureaus and other sources could be 30 points, or more, higher than comparable FICO scores.

This situation led some to label these alternative scores as “FAKO” scores, with the clear implication that the sellers are trying to deceive people with fake merchandise. That might not be quite fair, but the bureaus’ repeated insistence that “a credit score is a credit score,” and that it doesn’t matter which one you get, is disingenuous.

It’s true that the FICO scores you get from MyFICO.com might not be exactly the same as the FICO scores your lenders pull, because lenders use different versions of the FICO and those versions can be tweaked for different industries. But at least you’ll be in the right ballpark.

If you’re getting one of these alternative scores for free, it might not matter to you that you’re not seeing an actual FICO. If you’re paying for the score, though, you should make sure you’re getting what you expect. If it doesn’t say it’s a FICO, it’s not a FICO.

There is another scoring formula, though, that’s gaining ground with lenders and consumers: the VantageScore.

The three major credit bureaus—Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion—made a big splash in March 2006 when they announced this new credit-scoring system. In an unprecedented move, the three competing bureaus worked together to create a scoring system to rival the entrenched FICO.

Using words such as innovative, consistent, and accurate, the bureaus strongly implied that they had created a better mousetrap.

Many media outlets picked up the hype, proclaiming that VantageScores were an improvement on the FICO scores that most lenders use. Articles and broadcasts proclaimed the new credit score was “great news for consumers,” that it would “simplify” or “remake” the credit application process. One columnist even proclaimed, with little apparent evidence, that “creditworthy people...are more likely to get credit now.”

People who know about credit scoring took a decidedly more “wait and see” attitude. So far, VantageScore has not managed to push FICO off its perch as the leading credit score. But unlike other competitors, VantageScore has gained at least a toehold in the credit scoring market. The bureaus announced in 2015 that the formula was being used for at least some lending decisions by 2,000 lenders, including 6 of the 10 largest banks, and that nearly 1 billion VantageScores had been pulled so far.

Even more important, an additional 3 billion scores had been pulled for modeling and testing purposes—indicating many more lenders are in the process of adopting the formula. All the activity indicates that VantageScore has become a solid competitor to the venerable FICO score.

Furthermore, VantageScore has made arrangements with several consumer sites to offer its scores for free, including CreditKarma, CreditSesame, Credit.com, and Quizzle, among others. And VantageScore revised the language for its reason codes, which explain what’s affecting a score, to make them more understandable to the average person. All this outreach has helped boost VantageScore’s profile.

The VantageScore Scale

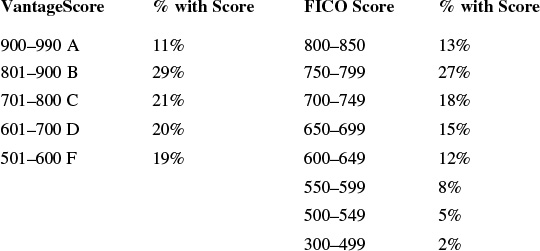

Initially, the VantageScore used a totally different scale from the FICO: VantageScores ran from 501 to 990. To make the score more “intuitive,” the bureaus designed each tier to correspond to the alphabetic grading system that most of us know from elementary school:

901–990 equals A credit

801–900 equals B credit

701–800 equals C credit

601–700 equals D credit

501–600 equals F credit

At the time the bureaus announced the VantageScore, they released statistics showing the percentage of population with each “grade.” Put those statistics next to similar statistics supplied by Fair Isaac for FICO scores, and you’ll soon notice something interesting.

The two scoring systems manage to put similar percentages of people in their highest three tiers. The FICO scale offers more tiers at the lower end than VantageScore, but the percentage of folks in the basement appears roughly the same.

Under the VantageScore system, 19 percent of borrowers at the time had F credit. If you use a FICO score of 620 as a cutoff point for subprime credit, you get similar results: Fair Isaac said that 19 percent of consumers had FICO scores below 620.

The bureaus and Fair Isaac cautioned against drawing conclusions from this comparison about where any consumer might stand in one system versus the other. But people did, and some wondered why a 750 score would be considered very good in one system and mediocre in another.

Consumer confusion wasn’t the only downside of VantageScore’s 500-to-990 scale. Lenders had built their software systems around FICO’s 300-to-850 scale, and they weren’t eager to make the changes needed to accept a different scale. Even FICO, with its ill-fated NextGen score, failed to persuade its customers that it was worth the effort. So perhaps it’s not surprising that VantageScore eventually switched to the 300-to-850 scale with its latest version, 3.0.

VantageScore 3.0 made a few other important changes. It stopped counting paid collections, saying they weren’t predictive of future default. It also looked back farther into the credit histories of people who hadn’t recently used credit. As you’ve read, FICO requires at least one account to be updated within the previous six months. VantageScore looks back 24 months. Finally, VantageScore can generate a score for someone whose credit is just 30 days old. FICO requires that people have one account that’s at least six months old. Those last two features mean as many as 35 million more people can be scored with VantageScores.

How VantageScores Are Calculated

Like FICO scores, VantageScores are calculated using the information in your credit reports. The factors considered are similar—your payment history, your balances, your credit limits, how long you’ve had credit, how recently you’ve applied for credit, and the mix of credit accounts in your file.

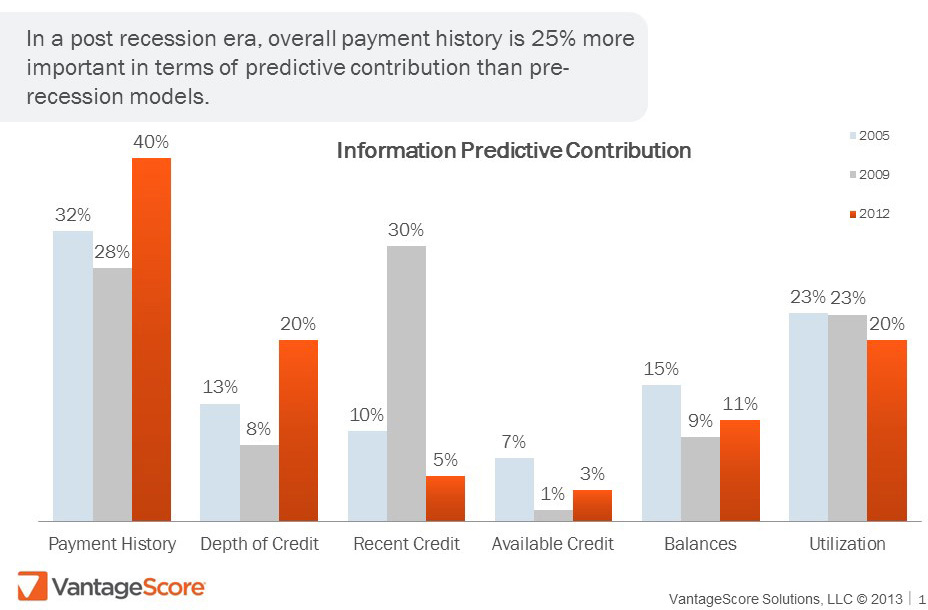

Exactly how each of these factors was weighted has changed over time as the score evolved (see Figure 3.1). Initially, for example, “recent credit activities” made up about 10 percent of VantageScore 1.0. In the second version, that was bumped up to 30 percent. In 3.0, it was demoted back to a “less influential” factor, comprising 5 percent of the score.

Which leads us to another change. VantageScore Solutions, the company that offers the formula, is trying to move away from the “35 percent is this, 30 percent is that” explainer that proved so helpful to understanding FICO scores. VantageScore says those “pie charts” are misleading because what might heavily influence one person’s score might be less relevant to another’s.

So now the company mostly talks about how influential factors are. Your payment history—essentially, paying bills on time—is “extremely influential.” Age and type of credit, and credit utilization, are “highly influential.” “Moderately influential” are the total balances you owe. Recent credit behavior and inquiries, and available credit, are “less influential” factors.

This means at least some of the basic rules are the same between the systems. Here’s how to protect and improve your score:

• Pay down your debt.

• Don’t open too many new accounts too quickly.

So Which Is Better?

The bureaus say they built VantageScore from the ground up, using their own expertise and databases. When announcing the new scoring system, the bureaus were careful not to compare it directly to the FICO score. In fact, when asked, bureau spokespeople continue to say that the VantageScore formula hadn’t been tested head to head with the FICO.

What VantageScore says to lenders is that its 3.0 score is more predictive than unspecified “benchmarks,” and that it does a better job of predicting which prime and near-prime consumers will default.

VantageScore’s Future

When VantageScore was announced, many credit experts predicted the new system would have a tough time unseating the classic FICO score. That assessment appears to have been correct, but the score is doing better than some expected.

Changing to a FICO-style scale doubtless helped. The scale is deeply embedded in the complex, highly automated formulas that lenders use to evaluate current and potential borrowers. Switching to a new range can be expensive and difficult. Credit expert John Ulzheimer, who has worked for both Equifax and Fair Isaac, put it this way: “It’s kind of like spending $10,000 to replace a $1 part, and the $1 part isn’t even broken.”

VantageScore also made strides in getting its score accepted for the process that Wall Street calls securitization, in which loans are bundled up and sold to investors. FICO scores have long been used to evaluate and price these investments, but now VantageScores are sometimes used as well.

One nut VantageScore has yet to crack is the same one that FICO has struggled with: getting major mortgage buyers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to accept a new score. Most mortgage loans are made under the guidance of these two “government-sponsored enterprises,” and that guidance has specified that lenders use a version of the FICO that’s now several generations out of date.

The wheels of government certainly turn slowly, but VantageScore still hopes those wheels will soon turn in its favor. Other regulators have accepted the score, the company says, so it may be just a matter of time before the mortgage industry catches up.

Of course, the bureaus have a strong incentive to win over lenders and rating agencies: money.

Every time a bureau generates a FICO score for a lender, the bureau has to pay a fee to Fair Isaac. It’s a profitable business for the company: According to Merrill Lynch analyst Edward Maguire, credit scoring at one point accounted for 20 percent of Fair Isaac’s revenues but 65 percent of its operating profits.

By creating and selling their own scoring system, the bureaus cut out the middleman.

The bureaus individually have tried to break Fair Isaac’s grip on the credit-scoring market before without much success. They’re hoping this joint effort—which promises a FICO-like consistent scoring formula across all three bureaus—will win over lenders who were reluctant to buy bureaus’ previous efforts to create proprietary scores.

A side note here: In unveiling the VantageScore, the bureaus made a big deal about its consistency. They touted the fact that their formula could take into account the different ways that the bureaus reported various bits of credit information and deliver scores that were consistent and comparable across all three agencies.

That caused some in the media to conclude that the FICO methodology is somehow different at each bureau. In fact, consistency has long been FICO’s trademark. It, too, uses the same formula across all three bureaus, with minor tweaks designed to accommodate the reporting differences at each agency.

Most of the variation in consumers’ scores among the three bureaus is caused by differences in the underlying data. You might have accounts reported at one bureau that don’t show up at the other two, or you might have successfully disputed an error at two of the bureaus that still shows up at the third. Neither the FICO nor the VantageScore fixes that problem; it’s still the information on each bureau’s credit report—accurate or not—that’s used to calculate the scores.

Other Scores Lenders Use

Credit scores aren’t the only scores—or even the most commonly used scores—lenders use to judge you.

Your credit card issuer checks your credit scores when you apply for credit and perhaps once a month after that. But your issuer also consults other scores, some of which are generated every time you use your card. The most commonly created score is a transaction score, designed to flag whether the purchase being made might be fraudulent. Other scores help determine

• The kind of credit card offers you get

• Whether your credit limits are raised or suddenly lowered

• Whether your card issuer calls you about a suspicious transaction, blocks it, or shuts down your account

• How cooperative your issuer is about waiving fees or lowering your interest rate

• How quickly your issuer calls you if your payment is late

• Whether a collection agency contacts you about an old debt and how hard it pushes

Here are some of the scores and what they’re designed to do:

• Application score—This score factors in data from your credit application that’s not included in your credit scores, such as your income, how long you’ve lived at your current address, and how long you’ve worked for your current employer. Lenders usually use application scores with other scores, such as credit and bankruptcy scores, to decide whether to grant you credit, how much credit to extend, and what rate to charge.

• Attrition-risk score—Lenders don’t want to lose their best customers, so they use attrition risk scores to try to figure out how likely you are to bolt to a competitor. Again, this score is used in combination with others to help the lender decide what to do next. If your account is profitable and you’re seen as a low risk for default or bankruptcy, the company might try to win you back by lowering your rate, boosting your limit, or deluging you with convenience checks. If your attrition risk is high but so is your risk of default, the issuer might just let you go.

• Bankruptcy score—Credit scores typically predict the chance you’ll miss a payment in the next two years. Bankruptcy scores predict the likelihood you’ll stop paying entirely and seek to legally erase your debt. Most lenders use both to help assess the risk that you won’t pay.

• Behavior score—Credit scores provide a broad overview of how you’re handling all your various credit obligations. Behavior scores, by contrast, focus on how you handle a single account with the creditor who’s calculating the score. Do you pay off your balances every month, carry a balance occasionally, or frequently pay only the minimum? That’s not information that can be gleaned from a credit report, but the creditor can find this data in its own files. Lenders often use behavior scores along with credit and bankruptcy scores to decide whether, for example, an overdue payment is an unintentional lapse (maybe you’re traveling) or a sign that you’re in serious trouble.

• Response score—Only a tiny fraction of the credit card offers sent out in the mail generate an application. Lenders use response scores to try to boost that tiny fraction a tiny, profitable bit more. Response scores predict the likelihood a consumer will respond to an offer of credit, such as a new card or a balance transfer offer. Credit card issuers use response scores to decide whom to target and how to customize offers to appeal to particular consumers.

• Revenue score—It’s all about the money, and revenue scores help lenders guess how much money—in interest payments, fees paid by the accountholder, and fees paid by merchants—an account is likely to generate.

• Transaction score—This is the score that’s run every time you use a credit (or for that matter debit) card. Transaction scores compare the potential purchase to your previous buying activity, as well as to known patterns of fraud. A small purchase followed by a much larger one can be one red flag because fraudsters often “test” a card with a small purchase to make sure it’s active before using the card to buy high-priced items that can be fenced. The rate of “false positives” for transaction scores is high; 20 purchases might be red-flagged for every one that’s truly bogus. It’s up to the issuer to decide where to set the bar that triggers account suspensions or review. Set it too high and the issuer can lose too much money, but setting it too low can aggravate customers by abruptly shutting down their accounts.

• Collection score—The scoring doesn’t stop after you’ve defaulted on a debt. Collection agencies look for signs that you might be able or ready to pay, and collection scores can help them sort their list of debtors so the most likely prospects float to the top. The scores look for a variety of evidence that your financial situation may be improving, from better credit scores to another collector’s account suddenly being paid.

Unlike credit scores, these other algorithms are used entirely in the background—you’re unlikely to ever see the numbers being generated, and you have no legal right to request them. But they’re being generated all the same.