6. Coping with a Credit Crisis

A credit crisis—being unable to manage your debts—can come on slowly as the result of overspending for many years. The balances on your accounts grow and grow; pretty soon you’re able to make only the minimum payments, and then not even that.

Other times a credit crisis comes at you in a rush as a result of another financial setback—a job loss, a divorce, a major illness. Suddenly, you have more “outgo” than “income,” and you’re not sure where to turn.

Or your crisis could be the result of larger financial turmoil. After years of encouraging people to borrow money, lenders began sharply cutting back their risk in 2008 as a result of the financial crisis. They raised rates, chopped lines of credit, and closed or froze accounts. People who once enjoyed cheap credit, and plenty of it, suddenly found themselves with much higher rates and nowhere to turn. The situation worsened as the financial crisis rippled through the economy, throwing millions of people out of work and causing home values to plummet.

Many people facing credit and financial problems are hoping for some quick, magical fix. Some ask whether they should get a debt consolidation loan, use credit counseling, or tap their retirement funds. Jeff of Fair Lawn, New Jersey, is fairly typical. At 44, he’s accumulated more than $40,000 in credit card debt and is finding it tough to pay much more than the minimum balances he owes:

“I am seriously considering a disbursement [from a prior employer’s 401(k)] to pay off my credit card bills. I understand there would be 20 percent withheld immediately, and a 10 percent early withdraw penalty next year at tax time. I’m still young enough to put future earnings aside for my retirement. I’m ready to make the leap. Am I wrong with this assessment? So much cash goes from my income straight to the credit card banks that it seems to be a viable alternative. What do you think?”

Kathy of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, had $20,000 in credit card debt, racked up during a tumultuous period when her husband became disabled, a parent died, and she lost her job. She had enough equity in her home to pay the debt, but she can’t find a lender willing to lend her the money to refinance:

“I have a horrible credit report,” she emailed. “I missed two months of credit card payments when Dad died, and the balances are high. [I could] sell the house... but, boy, I hate to move. This farmhouse is our only stability, as is our neighborhood.”

The truth is that there frequently are no easy fixes when you’re in a credit crisis. Even solutions that seem like a silver bullet often end up having unintended consequences: on your pocketbook, to your credit score, and as to your future financial options.

How you handle credit problems will have a huge effect not only on your credit worthiness, but also on your financial future. The wrong move can sink you further into debt, devastate what’s left of your scores, and put your entire financial life at risk. The right moves can help you climb out of the hole stronger, wealthier, and more creditworthy than ever before.

If you’re in the midst of a crisis, you need to get to work right away to minimize the damage, evaluate your options, and steer your financial ship away from the rocks.

If you’ve already endured the crisis and are getting back on your feet, you can skip ahead to the next chapter—but you might find some important information here that could help prevent a future catastrophe.

The steps you need to take are fairly straightforward:

1. Figure out how to free up some cash—You might not need to tap every source of income you identify, but it’s good to know what’s available before you go any further.

2. Evaluate your options—If you find enough cash, you might be able to set up a repayment plan and put the crisis behind you. If you don’t, you have an array of tough but important choices to consider.

3. Choose a path and take action—You might not like all the consequences you’ll have to face, but further delay will simply make matters worse. The quicker you pick a plan and get started, the sooner your credit can start to recover.

Before you get started, you’ll want some breathing room—psychological “space,” if you will—to deal with your financial problems. If you’re stressed over bills, give yourself permission to take a deep breath, and know that by the end of this process, you’ll have a plan. If you and your partner have been fighting over money, try to declare a truce while you get things sorted out.

If debt collectors are hounding you, you have the legal right to send them a letter telling them not to contact you, and they’re required to comply.

Unfortunately, some collection agencies have taken to filing lawsuits against consumers who send them such letters or who refuse to answer their calls. They figure if you won’t talk to them on the phone, they’ll get your attention by dragging you to court and suing you over your debts. That, of course, can make your current problems even worse.

If debt collectors are making your life miserable or threatening lawsuits, you should download the free eBook Debt Collection Answers: How to Use Debt Collection Laws to Protect Your Rights by Gerri Detweiler and Mary Reed, available from DebtCollectionAnswers. com. I provide a few suggestions on dealing with collectors in the next two chapters, but this is a complicated area of finance with laws that vary widely across the country. You might need additional help that is beyond the scope of this book.

Step 1: Figure Out How to Free Up Some Cash

One of the most common mistakes people make in a financial crisis is not cutting back hard enough, fast enough.

Charlie, an animator, is a classic example. He knew when his last project ended that hundreds of his fellow animators were out of work and that the next job could be a long time coming. But he hoped for the best. He and his wife even continued paying for their children’s private schools; in fact, more than a third of the $150,000 they borrowed against their home equity line of credit went for tuition.

“My wife didn’t want to disrupt their lives or their schooling,” Charlie explained.

This refusal to cut back is far from unique, according to debt expert Steve Rhode, who blogs at GetOutofDebt.org. People in a financial crisis often put off trimming their budgets, hoping something will come along to save them. That kind of optimistic attitude is perfectly human—and can be perfectly disastrous. It doesn’t make much sense to insist that you can’t possibly take your kids out of private school only to wind up losing your home.

You might not be paying $50,000 for tuition, but chances are you could find plenty of ways to cut your expenses if you got serious. Perhaps you’re clinging to a car you can’t afford, an expensive cell phone plan, or a habit of eating out.

If you need help finding ways to cut costs, check out some of the many frugality-oriented Web sites, such as The Dollar Stretcher at www.stretcher.com, Get Rich Slowly at www.getrichslowly.org, or The Simple Dollar at www.thesimpledollar.com. You’ll also find whole shelves of books on this topic at your local library, with Amy Dacyczyn’s The Complete Tightwad Gazette the likely centerpiece.

Or maybe you need to take a hard look at some of your bigger bills. Even your so-called fixed expenses, such as your mortgage or rent, aren’t really set in stone. Rhode says he often counsels people who struggle to hang on to homes that are simply too expensive for them, when the smarter course would be to move.

Don’t panic quite yet. For the moment, you don’t have to do anything other than write down the potential savings you can identify. You might find it helpful to break those savings down into three categories:

• The easy stuff—Expenses you could ditch with little effort

• The harder stuff—Expenses that would require more sacrifice to trim

• The last-ditch stuff—Expenses you would cut only as a last resort

Again, at this point we’re trying to find potential sources of cash so that you can better evaluate your options. Just don’t close your mind to what might seem right now like drastic measures.

There are two other good ways to raise cash: selling stuff and making more money. If you can sell an extra vehicle, hold a yard sale, or auction unused items on eBay, you might free up a good chunk of change. You also might consider freelance work or a second job temporarily. If you’re already working full time, this can seem pretty daunting, but you might do something for a few months that you’d never sustain permanently.

You might notice that I haven’t included some of the most-touted “fixes” for credit problems: home equity loans, other debt-consolidation loans, and withdrawals or loans from retirement plans. That’s because these “solutions,” as typically applied, often make matters worse in the long run.

Home equity loans, lines of credit, and cash-out mortgage refinances are particularly seductive because they tend to offer relatively low rates and tax-deductible interest, to boot. But they come with big problems:

• Most people who use home equity to pay off credit card and other unsecured loans ultimately end up deeper in debt within a few years. That’s because they haven’t changed the fundamental problem of overspending that got them in trouble in the first place.

• Such loans usually turn what should be short-term debt into long-term debt. You could end up paying more in interest—and again, wind up poorer—than if you’d buckled down and just paid off the cards out of your current income.

• Using these loans to pay off credit cards, medical bills, or personal loans turns unsecured debt, which could have been erased in bankruptcy court, into secured debt that can’t be wiped out—and that puts your home at risk as well.

Many people who tapped their equity during the boom years found themselves “upside down”—owing more on their homes than they’re worth—as house prices plunged.

Most retirement plans are also protected from creditors’ claims in bankruptcy court and typically shouldn’t be used to pay off unsecured debt. In addition, a withdrawal from a 401(k) or IRA means you’re losing out on the tax-deferred returns that your money could earn in the plan if you left it alone. Every $10,000 you take out of a 401(k), for example, could cost you $100,000 or more in future retirement income, assuming it had been left alone to grow at an 8 percent average annual rate for 30 years.

The idea that you would protect your retirement or home equity instead of paying debts outrages some people. They feel every possible source of funds should be tapped to pay off debts you owe. If that’s the way you feel, fine. But you should remember that the credit card companies are going to thrive whether or not you pay your bills. How will you thrive in retirement if you’ve decimated your funds before you even get there? Hopefully, your finances will turn out to be healthy enough that you can pay off all your debts, but you should think twice, and then again, before raiding either your retirement or your home.

In addition to the long-term cost, withdrawals from 401(k)s, IRAs, and other plans typically incur heavy penalties and fees. Come April 15, you would face a tax bill equal to 25 percent to 50 percent of what you took out.

Loans from 401(k)s and 403(b)s have their own dangers: If you lose your job, you typically must repay the loan within a few weeks, or you’ll owe penalties and taxes on the balance.

Are there exceptions? Of course. You might decide to borrow from your 401(k) to pay the mortgage for a month or two to avoid foreclosure, for example. But if you can’t make your house payment any other way than by tapping your retirement funds, you can’t afford your home. You need to consider other alternatives—a regular sale if you have equity, a short sale if you don’t, turning the keys over to the bank in a “deed in lieu of foreclosure” exchange, or even letting it go through the foreclosure process. We’ll discuss those options more in a bit. In any case, your long-term financial health depends on your fixing these fundamental troubles, not merely delaying the day of reckoning.

As far as debt consolidation loans go, you’re almost certainly better off steering clear. There’s a lot of consumer abuse, if not outright fraud, in this area. High, hidden fees are common, as are loans that just stretch out your obligation and ultimately cost you more than if you’d paid off the original debt.

A similar warning goes for debt-settlement firms. Many of these outfits promise to settle your debts for pennies on the dollar—often, supposedly, without hurting your credit. In reality, debt-settlement tactics often leave your credit score in shreds, and sometimes the company simply disappears with your big up-front fee. If you choose this option, do plenty of research first.

Steer clear of any outfit that touts “debt-elimination.” These scams use cockamamie theories about the Declaration of Independence or “natural law” to argue that you don’t really owe what you owe. It’s not true, and you could lose thousands in “fees” for this bad advice.

If you really can’t pay all of your unsecured debts and your income is below the median for your area, your best bet often is to file for Chapter 7 bankruptcy rather than messing with half measures. You can get a fresh start, and you’ll have the money you otherwise would have thrown at these nonstarter “solutions.”

If you have unpayable debts and your income is above the median, you may have to choose between a Chapter 13 bankruptcy repayment plan and negotiating settlements with your creditors. If that’s the case, get advice from an experienced bankruptcy attorney before you proceed.

Either way, you need to know more about your choices.

Step 2: Evaluating Your Options

This step actually includes a number of other tasks, all of which take a little time but are essential to making sure you choose the right option.

Task 1: Prioritize Your Bills

If you’re being hounded by creditors or are simply stressed by debt, it can be easy for your priorities to get out of whack. You might wind up paying a credit card bill when the rent or mortgage is due just because a collection agency is making your life miserable. You’d be risking eviction or foreclosure over a bill that could be wiped out in bankruptcy court, or at least postponed without major consequences.

You need to be the one deciding how your bills get paid without undue outside pressure.

Once again, we’ll be dividing into threes: essential bills, important bills, and nonessential bills.

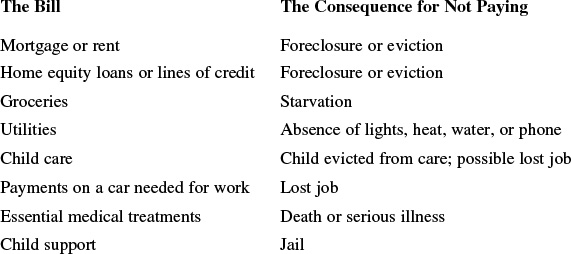

Essential bills are the ones that, if you don’t pay, will result in catastrophic consequences.

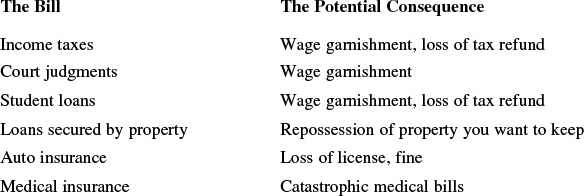

Important bills are the ones that you should pay if at all possible, because failure to pay them would have serious consequences. Here are some examples.

Nonessential bills include debts that aren’t secured by property. Failure to pay these debts could have serious repercussions for your credit score and might eventually result in lawsuits and judgments. But skipping the payments listed next won’t put you out on the street.

Nonessential Bills

Credit cards

Department store cards

Gas cards

Medical bills

Legal bills

Personal loans

Loans from friends or family members

You might have other bills not mentioned here; use your best judgment to categorize them.

After you have your list, go back and add two more columns:

• The monthly payment you typically make

• The minimum monthly payment you need to make to stay current

The minimum for most “friends and family” loans, by the way, is zero—unless you borrowed from your Uncle Tony, and his last name is Soprano.

Task 2: Match Your Resources to Your Bills and Debts

Look at the first two categories of savings that you identified in step 1—the easy stuff to cut and the harder stuff—and then add those to your monthly net income (what you get in your paycheck after all the taxes and other deductions have been taken). Now compare that income to your first two priorities—essential bills and important bills. Can you cover the minimums required?

If not, see whether you can trim the cost of some of these bills. Many people find they can cut back what they spend on utilities or groceries, for example. If you’re still straining, consider deeper cuts, like switching to a cheaper child-care option or taking in a roommate.

If that’s not enough, you might have some options before opting for the last-ditch cost-cutting measures. It’s frequently possible, for example, to get forbearance on your student loans or negotiate payment plans with the IRS. The first you can do yourself, just by talking to your lender; for IRS help, you’re probably best off using a tax pro. Even child support can be reduced if you prove to the court that your financial situation has worsened, but this can take awhile and might require a lawyer’s help.

Other possibilities: You might take that second job we talked about earlier. You could increase your paycheck by eliminating or reducing 401(k) contributions temporarily or, if you get a tax refund, by reducing your withholding.

If you still can’t pay for the essential and the important, you’ll probably need to take some last-resort action, such as selling a house if you own one or renting cheaper digs. You’ll also need to consult a bankruptcy attorney about wiping out any nonessential debts, because those obviously aren’t going to get paid.

If you have your bases covered and have money left over, however, check to see if you can pay the minimums on your nonessential bills. If you can pay at least that much, you’re ready for the next task.

Task 3: Figuring Out a Repayment Plan

Your mission: To see if you can pay off those nonessential debts, other than friends and family loans, in five years.

Why that particular time period?

Because that’s the standard generally used in bankruptcy court. If you have enough income and assets to pay most or all your bills within that time frame, a judge probably wouldn’t let you pursue a Chapter 7 bankruptcy.

You can find debt-reduction calculators on the Internet, at sites such as Bankrate.com and CreditCards.com. With these, you can experiment to see how long it might take you to pay off your unsecured debts. Similar tools are available in personal finance software, such as Quicken and Mint. Don’t include your mortgage, student loans, or any other “essential” or “important” bills we covered in the previous task; you’re just trying to design a plan for those nonessential debts.

First, see how much progress you can make with the increased income you identified; then add in the lump sums you’ve estimated that you could raise by selling stuff. Finally, check out how fast you could get out of debt if you took some of those last-ditch options.

You also could consider—carefully—using a home equity loan or line of credit to pay off your cards, if you have substantial equity and can find a willing lender. But do so only if you can commit to the following:

• Not using your credit cards to pile up more debt. (For most people, this will mean not using cards at all until the home equity borrowing is paid back.)

• Not borrowing more than 80 percent of your home equity (and preferably less) when your mortgage and home equity borrowing is combined. Home equity can be an important source of emergency funds that you don’t want to squander. (Some lenders won’t let you borrow that much, anyway. If home prices are declining in your area, you may have to shop hard to find a lender willing to let you borrow more than 60 percent or less of a home’s worth.)

• Paying off the debt in the same three- to five-year period. In other words, don’t use the home equity loan as an excuse to stretch out your debt.

Remember: If you don’t commit to these steps, you’ll ultimately just drive yourself deeper into debt.

In the best-case scenario, you’d be able to retire your credit card and other unsecured debt in less than five years without too much strain. If you still have good credit scores, you might even convince your lenders—just by asking—to lower your interest rate so that you can get the debt paid off faster. Credit card companies are often eager to give their best customers a break rather than risk losing them to competitors. If not, good credit scores typically mean other companies want your business; you may transfer your balances to other cards at lower rates. Check CreditCards.com, CardRatings.com, NerdWallet, and LowCards.com for current offers.

Of course, that particular door might be closed to you if you’ve already fallen behind on your payments. Late payments to even one of your creditors can cause your scores to fall to the point that other issuers won’t want to take a chance on you. You won’t get the low balance-transfer rates they offer to people with better scores, and you may not persuade them to grant you a new account, period. All this can make it that much harder to try to get your head above water.

If things are bad when you’re just late with a few payments, you can imagine how lenders—and your credit scores—react when an account is unpaid for so long that the original creditor “charges off” the account. A charge-off is an accounting term that means the lender has given up hope of collecting. Accounts are typically charged off if they’re unpaid for six months. Although some creditors then turn the account over to their internal collections departments, others sell the account for pennies on the dollar to outside collection firms.

Interestingly, it’s the charge-off itself that does the most damage to your score. Collection actions are serious, as well, but what matters most is what the original creditor says about your account—and a charge-off is pretty much the worst thing the creditor can say.

If you’re in this situation, consult the books I recommended at the beginning of this chapter for a detailed summary of your rights as well as the best strategies for negotiating with collection agencies. The fine points of dealing with collectors are well beyond the scope of this book.

But, as far as your credit score is concerned, keep these points in mind:

• Although late payments can hurt a credit score, a charge-off is even worse. If at all possible, try to avoid letting an account lapse for so long that it’s charged off.

• If an account has not yet been charged off, try to pay the balance in full either at once or over time. Settling the account with the original creditor for less than you owe can hurt your credit score. (Settlements on collection accounts typically don’t have as negative an effect; see the next chapter for details.)

• If an account has been sent to collections, you’ll have the most leverage to negotiate if you can pay a lump sum. But even if you have to make payments, try to negotiate to have the collection action deleted from your credit report if at all possible. Although having the collection deleted won’t erase the negative marks from your file—the most damaging mark is the charge-off, which the original creditor typically won’t drop—getting rid of the collection notation often helps your score.

What if you can’t find a way to get all your unsecured debts paid off, or you’re just not sure if your plan will work? You essentially have two options: credit counseling or bankruptcy. Read on for what you need to know about each.

The Real Scoop on Credit Counseling

For years we saw the ads on television, the radio, and the Internet promising to “lower your interest rates,” “reduce your monthly payments,” “end collection calls,” and “get you on the road to financial freedom.”

Sometimes credit counseling agencies delivered on their promises. Other times, consumers wound up much worse off. Just read what Jeff in Cincinnati went through:

“A little over five years ago, I contacted AmeriDebt to see if they could lower the interest rates on my credit cards. Within 30 minutes, I had received a callback from a representative from AmeriDebt stating that they had lowered the rates on my credit cards. I was amazed at the speed in which they had done this. I started paying them $500 a month, and they were to disburse the funds to my creditors. The problem was they never paid my creditors. [After five months], they had $2,500 of my money that the creditors should have received. This sent my credit into a tailspin. I was not in trouble with my creditors and had never missed a payment of any kind until I started dealing with [this company]. The credit card companies were calling, and they stated that they had no record of AmeriDebt working on my behalf. Bottom line: My credit was now ruined. I went from a 750 Beacon score to a 520 within four months. I paid everyone off immediately, and it has taken almost five years to get my credit score to just below 700. The funny part is that AmeriDebt decided to finally pay out that $2,500 to my creditors after I [had] already paid them off.”

AmeriDebt insisted that it helped hundreds of thousands of consumers pay their bills and avoid bankruptcy. It continued insisting, in fact, right up until the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) sued the company in 2003. The FTC said AmeriDebt lied to its customers about the fees it charged and the services it offered, leaving many of them worse off.

What’s more, regulators said, AmeriDebt posed as a nonprofit company while actually funneling money to a for-profit arm.

AmeriDebt responded by closing its doors to new customers—but sending them to another heavily advertised credit counselor making similar claims of quick-and-easy solutions to debt problems.

Credit counseling used to be a sleepy field dominated by the National Foundation for Credit Counseling, a truly nonprofit organization funded in large part by contributions from banks and credit card companies. Its mission was to negotiate lower interest rates and payments for cash-strapped consumers so that they could avoid bankruptcy. The lender receiving these payments would return a portion of each check—a contribution known as “fair share”—to the credit-counseling agency to fund its operations.

As consumer debt spiraled in the 1990s, however, a new breed of credit counselor emerged, eager to get a piece of those lender contributions. To boost market share, these new counselors started going after customers who were perfectly able to make their payments but who just wanted a lower interest rate.

Disgusted, the major creditors started dropping their “fair share” contributions, making it tougher for the older agencies to make ends meet. Instead of supporting legitimate counselors, some credit card companies even tried to steer consumers away from counseling, telling them erroneously that such help was as bad for their credit as bankruptcy.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. Many of the new credit counselors kept the first month’s contributions or charged other fat, hidden fees. Some failed to pass along consumers’ contributions at all, causing multiple late payments that devastated scores. Former employees of such firms told Congress that they were forced to use fake names and employ high-pressure “boiler-room” tactics to sign up new customers. The emphasis was on collecting fees—not providing counseling or offering education that might help consumers understand how to avoid debt in the future.

Finally, things got so bad that the IRS decided to act. The federal tax agency began auditing dozens of credit counselors and eventually revoked the tax-exempt status of about half the credit counseling industry.

“Over a period of years, tax-exempt credit counseling became a big business dominated by bad actors,” the IRS’s then-Commissioner Mark W. Everson said in a press release. “Our examinations substantiated that these organizations have not been operating for the public good and don’t deserve tax-exempt status. They have poisoned an entire sector of the charitable community.”

The IRS’s move helped weed out some of the worst offenders, but you still need to be cautious if you’re considering getting help.

Keep in mind that credit counseling is not a good option if you’re current on your bills and can pay more than the minimums. As I explained in Chapter 5, “Credit-Scoring Myths,” credit counseling itself won’t hurt your credit score, but the reactions of some of your lenders might.

If you’re already struggling, here are some of the things you need to consider before signing up with a credit counselor:

• Is it accredited? You’ll want a counselor affiliated with the National Foundation for Credit Counseling or the Financial Counseling Association of America (formerly the Association of Independent Consumer Credit Counseling Agencies). You can find affiliated agencies at www.nfcc.org or www.aiccca.org, respectively.

• What do regulators say about it? At a minimum, make two calls: one to your local Better Business Bureau and one to your state attorney general’s office. Ask how many complaints have been made about the agency, and determine whether any regulatory actions are pending against them.

• What does the agency say about its services? Avoid an outfit that says credit counseling will have no negative impact on your credit or one that promises to settle your debts for less than you owe without affecting your credit. Such unrealistic promises are a clear sign that you’re not dealing with a legitimate operator.

• What fees are involved? Legitimate credit counselors have had to raise their fees in recent years, but if you’re paying much more than $50 to set up your plan, you’re probably paying too much.

• When and how much will creditors get paid? You know that missing or late payments can devastate your credit score. Make sure the counselor tells you, preferably in writing, how much of each monthly payment you make will go directly to your creditors and when the payments will arrive.

It’s possible that after all this investigation, you’ll discover that a credit counselor’s debt management plan won’t work. If your credit counselor crunches the numbers and discovers the agency can’t help you pay off your bills within five years, you’ll probably be told to “explore other legal options.” That’s code for: Talk to a bankruptcy attorney.

You might want to do that anyway, just to get more information about your options before you decide on a plan. Such a consultation is particularly important if your debts are overwhelming and you have equity in a home. States treat this equity differently, with some protecting all or most of it in bankruptcy court and others figuring it’s up for grabs. If you can’t protect your equity, it might be worth getting a home equity loan to pay off your debts, assuming you have enough equity available.

After you’ve heard what both the credit counselor and the bankruptcy attorney have to say, you can weigh all the information you’ve been given and make a choice.

Debt Settlement: A Risky Option

As bogus credit counselors have been shut down, a new breed of firms promising debt deliverance has taken over airwaves and the Internet. They essentially promise to settle your debts for pennies on the dollar.

Although the schemes vary somewhat, the basic idea is that you stop paying your bills and instead save up the cash that the firm will then use to negotiate a settlement of your debts. Failing to pay your bills on time will, of course, trash your credit scores, and settlements, especially with your original creditors, can do additional damage.

The worst of these firms make unrealistic promises, assure you your credit won’t be harmed, and disappear after taking thousands of your dollars. Even working with a legitimate firm can lead to lawsuits and wage garnishment as creditors retaliate.

In 2010, the Federal Trade Commission forbade debt settlement firms from charging upfront fees for their services. The FTC also implemented new rules requiring more disclosure and more safeguards for any funds customers put aside to pay their bills. There are still plenty of firms trying to skirt these new regulations, though, so it’s still buyer beware.

Debt settlement makes little sense for people who can successfully file a Chapter 7 bankruptcy (details on that later) to erase most unsecured debts. If you can’t pay your bills, after all, you’re financially much better off eliminating the debt entirely and saving yourself the debt-settlement firm’s fees and the risk of lawsuits.

If you can’t file for Chapter 7 and would face a five-year Chapter 13 repayment plan instead, debt settlement might be an option. Debt settlement could have you free of your bills in two to three years. But you’ll want to choose your company carefully.

The Federal Trade Commission has said legitimate debt-settlement companies should

• Not guarantee results.

• Not accept clients who have the means to pay their bills.

• Have written policies and procedures about their debt-settlement program.

• Be a member of the Better Business Bureau.

• Have a customer dispute-resolution and review process.

• Have in-house legal counsel with significant experience in credit industry compliance.

• Handle clients in-house, never referring them to a third party.

• Offer full disclosure of all program fees and costs before the start of a debt settlement program.

• Inform customers that the IRS classifies any forgiven debt above $600 as income that can be taxed.

• Require prospective clients to commit to saving money on their own to fund settlements. This money shouldn’t be handled or escrowed by the debt settlement firm because of the risk of embezzlement and fraud.

• Negotiate on an ongoing basis with creditors and present all settlement offers to the customer for his exclusive approval.

Credit expert Gerri Detweiler of Credit.com says you should avoid any company that assures you that

• It can settle debt without hurting your credit.

• You can’t be sued. (You can!)

• It can stop creditors from calling you. (It can request that they stop but can’t prevent them from ignoring this request.)

• It can predict how much you’ll save or exactly how much the settlements will cost.

In addition, Detweiler says any of the following are also red flags:

• Fees aren’t based on performance or results—Detweiler doesn’t like companies that collect money up front or based on a percentage of your debt.

• Counselors are paid on commission—Detweiler believes this increases the chances counselors will lie to get you in the door.

• No money-back guarantee—You should have at least 30 days to change your mind and receive a refund of at least some of your fees if none of your debts are settled.

• Inexperience—Many companies have sprung into existence recently and have little experience successfully negotiating settlements.

Should You File for Bankruptcy?

In the fall of 2003, I asked MSN readers to share their bankruptcy stories: why they filed, how it has affected them, and whether they thought they made the right choice. I expected a few dozen replies.

I received more than 500 emails. I was stunned not only at the breadth of the response, but also the depth. Most were long, detailed missives that recounted financial catastrophes, such as lost jobs and huge medical bills, personal tragedies including the death of a spouse or a child, and a wide variety of human miscalculations: trusting the wrong business partner, marrying a secret gambler, or simply spending way more than they earned.

Most believed that filing bankruptcy was the right choice for them; although many admitted to mixed feelings. Here’s just a small cross-section of their responses:

“I filed last year and released about...$40,000 in credit card debt. I researched and pondered the idea for quite awhile before actually doing it, but ultimately it provided me a fresh start. Now I am a regular, financially upstanding citizen, and I have learned my lesson.... Had I not been protected by bankruptcy laws, I would still be struggling.”

—Erin in Honolulu

“I don’t think bankruptcy is ever the ‘right’ decision, but I felt it was my only choice at the time. For me, it was embarrassing and humiliating.... It is now six years later, and I’ve done all I can to restore my credit by making sure all my bills are paid on time, and I pay all my debts as quickly as possible. The children are both now grown and on their own, I’m making twice the wages I was [at the time of the filing]... that doesn’t make any difference. I still have trouble getting credit.”

—Cathy in Montana

“I filed bankruptcy in 1998 and have gotten myself in trouble once again. Currently I’m about $3,000 in debt, which consists of cell phone bills and credit cards that started out with a limit of $300 or $500...all of which are probably in or close to being in collection.”

—Leslie in Washington, DC

“We filed Chapter 7 in 1999 due to bills piling up as a result of [our business failing]. One year later, we applied and were approved for a credit card with a 13 percent interest rate. I also bought a new car at what I consider a somewhat outrageous rate of 16 percent and missed out on all the 0 percent financing offered after September 11. Basically, one can survive a bankruptcy as long as the pay history is kept up to date on all debts afterward.”

—Rob in Grand Prairie, Texas

“It has been almost four years since I sat in an attorney’s office, papers filled in ready to file for bankruptcy. I was a newly sober alcoholic wanting to make a fresh start in my new life.... I decided that filing for bankruptcy was a cop-out, and that it was unfair to the companies (small and large) that I had defaulted on. Since that day, I have [been making payments].... In April 2007, my record will be clear of all negative items, and I achieved this without filing bankruptcy.”

—Ken in Santa Rosa, California

As you can see from these responses, people’s experiences with bankruptcy can vary widely. Whether it’s the right choice depends on the types of debt you owe and the amounts, your income and resources, and your ability to navigate the inevitable fallout, among other factors.

The Effects of Bankruptcy Reform

In 2005, after several years of trying, Congress finally succeeded in passing a bankruptcy reform act to make erasing debts more difficult for higher-income borrowers. These debtors would be subjected to a “means test” that was supposed to determine whether they could repay some of their debts.

The new legislation set off a stampede, as debtors rushed to file bankruptcy before the new limitations went into effect. By the end of the year, more than two million cases had been filed—a number that shattered all previous records.

Publicity about the new law led to a lot of misconceptions. Many people believed, erroneously, that bankruptcy had been eliminated as an option or that everyone who filed would be forced to repay at least some of what they owed.

In reality, the new means test applies only to filers whose incomes are above the median level for their area. Most people filing for bankruptcy have incomes below the median, so they aren’t subjected to the means test. For them, the biggest impact of the reform is that filing for bankruptcy has become significantly more costly than in the past. A typical Chapter 7 may cost $1,200 or more in filing and attorney’s fees, whereas a Chapter 13 bankruptcy can cost $3,000 and up.

Still, that didn’t prevent bankruptcy filings from rising as the economy soured. Filings in 2008 topped one million—back to the same level that prompted lenders to begin lobbying for bankruptcy reform a decade earlier—and in 2010 consumer filings topped 1.5 million.

The Type of Bankruptcy That You File Matters

The majority of people who file for bankruptcy opt for Chapter 7, which wipes out most unsecured debts. (Unsecured debts are those that aren’t linked to specific property, such as a car or a house. So your mortgage is a secured debt; your credit card bills are unsecured.)

Filing a Chapter 7 bankruptcy can mean you have to give up some of your assets (property or cash) to pay your creditors. In reality, most Chapter 7 filers aren’t required to give up anything, either because they don’t have any assets or because the property they have is “exempt” or protected from creditors. The exemptions vary by state, but they might include household furnishings, clothing, tools you need for work, retirement accounts, and some—or all—of the equity in your home.

If you want to keep property that isn’t exempt, you can still file for bankruptcy, but you typically must choose Chapter 13. You also might be shunted into a Chapter 13 bankruptcy if your income is above the median for your area and the new bankruptcy reform means test shows that you can repay some of what you owe.

Chapter 13 requires debtors to come up with a five-year repayment plan. If they successfully complete their plan, they’re allowed to keep their property while having any remaining debts erased. Unfortunately, most people fail to complete their Chapter 13 plans, and their cases are either dismissed, allowing creditors to resume collection activities, or converted to Chapter 7s.

A bankruptcy filing can make sense if any of the following apply:

• You can’t pay back your unsecured debts, such as credit cards and medical bills, within five years.

• You don’t have much equity in a home or vehicle or much other property to speak of.

• You do have considerable equity in a home or vehicle or other valuables that wouldn’t be exempt in bankruptcy—jewels; family heirlooms; valuable artwork or collections; or stocks, bonds, and cash held outside a retirement plan—but you’re willing to agree to a Chapter 13 repayment plan rather than a Chapter 7 liquidation.

Bankruptcy might not make sense if any of these apply:

• You could repay your debts within five years.

• Most of your debts are the kind that can’t be wiped out. Debts that typically can’t be erased include student loans, child support, and recent taxes. You might still decide to file so that you can free up more money for these debts, but the disadvantages of filing might overwhelm the advantages.

• You defrauded your creditors by hiding assets, say, or lying about your income or debts on a credit application.

• You recently ran up large debts buying luxuries, which can include vacations and entertainment. If you did so while you were clearly broke, that can constitute fraud. If you ran up the bills and then lost your job, you might be able to file for bankruptcy on other debts, but the luxury debts might not be wiped out.

• You want to file a Chapter 7 liquidation bankruptcy and received a discharge for a previous bankruptcy filing within the past eight years. (You can file for a Chapter 13 repayment plan bankruptcy at any time.)

• You’re reluctant to leave a coborrower solely responsible for a debt. A bankruptcy filing can wipe out your legal obligation to repay a loan, but creditors can still go after a cosigner or joint borrower.

Making the decision to file isn’t an easy one, and you’d be smart to get expert help to explore your options. Many bankruptcy attorneys offer a free initial consultation. For more information, a good book to read is The New Bankruptcy: Will It Work for You? by attorneys Leon Bayer and Stephen Elias (Nolo, 2015).

Should You Walk Away from Your Home?

Loose lending standards put many people into homes they ultimately couldn’t afford. Others found themselves struggling to pay their mortgages after they lost their jobs. And still others decided to walk away from homes they could afford because their properties were worth less than what they owed. These so-called strategic defaults accounted for about one in three foreclosures in 2011.

People who voluntarily default often reason, probably correctly, that their credit scores may heal before property values do. Although property values have rebounded in many areas, they’ve been slow to recover in others. Seven years after the real estate recession began, prices had yet to return to their peaks in 40 of the 50 largest markets, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of home sales data from Zillow. Meanwhile, as you learned in a previous chapter, someone with FICOs in the 680 range would recover her old scores in about three years, while someone with 780 FICOs could reattain her old scores in seven years or so.

Still, the decision to stop paying a mortgage is a difficult one for many people. As the recession worsened, many tried to get mortgage modifications or refinancings from their lenders, only to have their paperwork repeatedly lost or their applications rejected for bogus or trivial reasons. Some were approved for trial modifications—and then the lender moved forward with foreclosure anyway. (In one particularly tragic case, a couple’s daughter and her grandparents were killed in a traffic accident. When the couple asked for more time to file their paperwork as they dealt with this horror, their bank responded by sending them a foreclosure notice.) Bankruptcy attorney Stephen Elias told me that many of his clients who originally insisted they had a moral obligation to pay their loans had that attitude beaten out of them by the indifference, avarice, or seeming incompetence of their lenders.

If your mortgage is problematic, your first step should be to contact a HUD-approved housing counselor (www.hud.gov) who can assess your situation and advise you about alternatives. You may qualify for help through a government-sponsored modification or refinance program, or you may work out a more affordable arrangement directly with your lender. Although some frustrated homeowners have said they couldn’t get their banks’ attention until they stopped paying their mortgages, you are not required to be behind on your payments to get help—and not paying your mortgage will have significant negative impacts on your credit scores.

If you can’t get help, you should assess whether your mortgage is truly affordable. The federal government typically defines an affordable mortgage as one that consumes 31 percent of the borrower’s gross income. In my view, a mortgage that eats up much more than 25 percent of your gross income may not be workable, because you may not have enough money left over to cover other important costs such as saving for retirement, building an emergency fund, and educating your children.

Too many people throw half or more of their incomes at a mortgage—a situation that is simply not sustainable in the long run. What’s worse is when people raid their retirement funds to make their mortgage payments, draining their future nest eggs for a home they might ultimately lose anyway. Before you withdraw or borrow money from a retirement fund to pay a debt—any debt—you should talk to a bankruptcy attorney about the legal and financial repercussions of what you’re doing.

If you know you can’t afford your mortgage, you have several options:

• A short sale—If the lender agrees, you may be able to sell your home for less than what you owe. Although a typical short sale has the same impact on your credit scores as a foreclosure, you should qualify for another mortgage after two years, versus a wait of up to seven years after a foreclosure. Always have your own attorney review any short sale agreement, however. Lenders have been known to pursue borrowers for unpaid mortgage amounts, even after agreeing to a short sale. You’ll want clear language in the agreement that you’re no longer on the hook for this debt.

• Deed-in-lieu of foreclosure—You’re essentially handing the keys over to the bank rather than waiting to go through the formal foreclosure process, which would otherwise take months if not years. Your credit scores will still suffer; although you may qualify for another mortgage sooner, as with a short sale. Again, try to make sure you can’t be pursued for the leftover debt.

• Foreclosure—The formal foreclosure process varies by state—some go through the courts; some don’t. Some states don’t allow lenders to pursue borrowers for unpaid debt after a foreclosure, while some do. The details vary enough that you’ll want to research your particular state’s laws and discuss your situation with a bankruptcy attorney or other lawyer familiar with the credit laws—and lender practices—of your state. Foreclosure has one big advantage over a short sale or deed-in-lieu in that it takes longer. Why is that a good thing? Because you can continue living in your home, rent free, while the process grinds on. If you save up the money you would otherwise commit to mortgage payments, you’ll have a stash that can help you in your post-foreclosure life—by making a big deposit that could convince a reluctant landlord to rent to you, for example.

Before you choose any of these options, you should read attorney Elias’s book The Foreclosure Survival Guide: Keep Your House or Walk Away with Money in Your Pocket” (Nolo Press, 2009; co-authored with Amy Loftsgordon) and discuss your situation with a qualified attorney.

A new twist on the crisis has begun to emerge in recent years, as much higher payments kicked in on home equity lines of credit taken out at the market peak. These lines of credit typically require only interest payments in the initial 10 years, but after that time switch to a payment that includes principal as well as interest.

Homeowners with sufficient equity, incomes, and credit scores may be able to qualify for a new home equity line that puts off the day of reckoning. Another option might be a “cash out” refinance of their primary mortgage to pay off the line and essentially add its balance to the first mortgage.

Those who aren’t in a good position to get another loan should contact their lenders to see if there is a workable solution. To lower payments, some banks have been willing to extend the payback period or defer interest until the end of the loan.

Step 3: Choose Your Path and Take Action

When faced with unappealing choices, it’s natural to procrastinate. But after you’ve assessed your situation, gathered the relevant information, and sought expert help, the path you need to take should be pretty clear.

Option 1: The Pay-Off Plan

If you can pay off your unsecured debts without help or with the help of home equity borrowing, you’re ready to take the first step: cutting up your credit cards. “What?” you might be saying. “Cut up my cards? How can I live without my cards?” News flash: People do it all the time.

You can’t get out of debt if you keep digging. And if you have easy access to your cards, you’ll keep using them. Your credit cards—at least most of them—need to be off limits until you’re debt free. Debit cards with Visa or MasterCard logos are accepted at most places that take credit cards; the difference is that the money comes directly out of your checking account, so it’s much tougher to overspend.

The big risk with debit cards is fraud. If a criminal gets hold of your account number, she can drain your bank account—and then you’ll have to wait to get your money back. The computer-chip technology that banks are finally adopting will help curb fraud, but you’re still at risk as long as your card has a magnetic stripe on the back because those are easily compromised. If you’re not comfortable using your debit card—and that’s a reasonable attitude—then consider using a credit card that currently has no balance for purchases you can’t make with cash. The key is paying this card in full every month. If you can’t do that, then use cash.

You don’t need to actually close your credit card accounts, which could potentially hurt your score, unless you really have an uncontrollable spending issue.

Next, set up an automatic payment plan as outlined earlier to pay off your debts. The order in which you pay them depends on your particular situation. If you have an account that’s close to being charged off, for example, you’ll probably want to catch up with that one right away while paying the minimums on your other debts. If you’re not behind, you could start paying down the account that’s closest to its limit, or the one that’s charging the highest nondeductible interest rate. After the first debt is retired, redirect the biggest payment to the next-highest-rate—or closest-to-the-limit—debt. Continue this pattern until all the debts are retired.

Option 2: Credit Counseling

If you decide you need a credit counselor’s aid, make the appointment to get started on a debt management plan. Every day you delay is costing you more in interest and putting off the moment when you’ll be debt free.

Understand that paying off your debts will be a long-term commitment, and that living on the tight budget necessary may be frustrating. If you need motivation to keep going, consider joining the message boards of one of the frugality-oriented Web sites to get support and keep your spirits up.

Option 3: Debt Settlement

Before you agree to debt settlement, make sure you’ve consulted a legitimate credit counselor and a bankruptcy attorney so that you understand your other options. Thoroughly research the debt-settlement firm before agreeing to its services. Commit to setting aside the money you’ll need for settlements—many people drop out of debt settlement after just a few months because it’s too tempting to spend the money on other things.

Option 4: Bankruptcy

If bankruptcy is the best of bad options, then file. The bankruptcy laws were designed to give people a fresh start; and if you’ve done your best to find money to pay your bills and failed, you shouldn’t shun this option.