Chapter 11

Killing Zombies and Preventing Their Return

In late 2008, when banks worldwide were bleeding with huge losses from the subprime crisis, and the U.S. Congress had just given authority to the administration to buy some of the bad assets from the banks, Thomas M. Hoenig, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, called up his colleagues at the Swedish central bank. Because the Swedes’ handling of their banking crisis a decade earlier is considered to be among the best reactions and approaches to such a disaster, Hoenig wanted to get some details about how they’d done it. The Swedish officials were very helpful and thorough with their explanation of the way failing banks were swiftly cleaned up and returned to health in the early 1990s, Hoenig recalls. After hearing their story in detail, Hoenig asked his Swedish counterparts: “This makes a lot of sense. Has anyone from the U.S. talked to you about doing that because you have experience?” The response wasn’t very assuring: “Absolutely not. Nobody else has called.”

The Swedes, like the Americans and the Europeans in 2008, were also faced with two options when their banks fell apart in 1991. They could turn a blind eye to the banks’ losses, give them years to slowly write bad assets down and hope that their earnings over time would cover those. Or the government could force them to take the losses up front, recapitalize them, and make the shareholders suffer for the mistakes that had led to the crisis. Sweden opted for the second option, unlike Ireland, the United States, or Germany this time around, and it nationalized one-fifth of the banking system, moved the soured loans to a bad bank, and turned its economy around in two years.1

The initial U.S. approach smacked of the Swedish experience when former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson asked Congress for funds to buy toxic assets from the banks, under what the administration called the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). However, the strategy had to be revised quickly when Paulson realized that $700 billion was nowhere enough to buy the toxic stuff. He needed trillions of dollars to do that. So TARP was instead used to inject capital; banks were allowed to spread the losses over time so they could slowly earn their way out, and interest rates kept at near zero percent to help them do so. Three years later, the weakest banks are still licking their wounds; more losses are piling up; the housing market is stuck in limbo; the economic recovery is faltering. Europe’s troubles are no less: Doubts about the periphery’s ability to pay their debt are growing, recession in the weakest countries is into its fourth year, the euro is in danger of bursting at the seams. At the heart of the problems in both continents lies the failure to fix the banking problems properly. But it’s not too late. The right policies can still be applied and the agony of the world economy can be shortened.

It has to start with taking a hatchet to the zombies, to cut the losses and help the turnaround. But to prevent zombies from returning (other banks turning into zombies) and causing the next crisis, there is also a need for tighter banking regulation than what governments have come up with so far. Just as in dealing with the zombie banks, the solutions to the problems facing the European Union (EU) and the United States also require the bitter pill of restructuring debt, be it the sovereign bonds of periphery countries in Europe or residential mortgages in America.

Aside from the creditors of Lehman Brothers and the Icelandic banks, debt holders of the banks were untouchable worldwide during the 2008 crisis and its aftermath. There’s no reason why they should be. If a bank is facing losses that exceed its paid-in capital, then creditors should bear the excess. If the bank has a business model that can still work and franchise value that’s worth saving, then the creditor-turned-shareholders can benefit from the eventual recovery and perhaps get most of their money back. When Citigroup was on the verge of collapse in 2008, it had about $350 billion of bonds outstanding. Converting those to stock would have given the bank enough of a cushion to weather losses and made it easier to come clean with all of the toxic stuff up front, says economist Joseph Stiglitz. “That way, you’d never need a bailout of Citi,” the Nobel laureate says. “Instead, the government suspended the rules of capitalism and came to its rescue.”

Ireland could have done the same with its banks when they ran into trouble. “The best way to capitalize the banks would have been debt-to-equity swaps,” says Kevin O’Rourke, a Dublin-based economist. Some of the Irish bank subordinated bonds (those that rank lower on the creditor hierarchy) have since been converted to equity or replaced with lower value debt, but not until after taking over the losses of the banks ran Ireland aground. The new Irish government elected in 2011 is pressing the EU to allow for senior bonds to be included in some debt-to-equity swaps as well, though it’s unlikely to succeed because European leaders strongly oppose the concept. Some bondholders of Bank of Ireland have offered to swap their holdings for shares since they probably believe the bank is the best situated among the Irish zombies and can actually be turned around—so the new owners can benefit from the upside.2

Politicians and regulators have shied away from burning the banks’ bondholders because that could lead to a repricing of bank debt for good, increasing their borrowing costs, says Adriaan van der Knaap, a UBS banker who specializes in bank funding. “Maybe unsecured senior debt of banks needs to be priced higher to reflect the risks inherent in banking,” Van der Knaap says. The authorities are worried that such an increase would get transferred by the banks to their customers through higher lending rates, which would hurt growth. That could be the case if nothing else is done to reduce the riskiness of banks. But if the banks aren’t allowed to gamble as much and forced to hold bigger capital buffers, then the risk to creditors would be reduced, compensating for the possibility of debt becoming shares. More on those needed measures later.

To remove the shackles on their economies, governments need to end the lives of zombies. If the implicit or explicit state backing is removed, then zombie banks couldn’t borrow or raise capital in the marketplace and would be forced to go extinct. Without the unfair competition from weakened but propped up rivals, the healthy banks can thrive, fill the void left by the zombies, and provide the lending needed for economic recovery. “Exit barriers for banks are very high,” says Carola Schuler, a banking analyst at Moody’s Investors Service, the ratings agency. Those barriers have to come down. Society pays to keep alive banks that should have died long ago.

Who Bears the Cost?

Although Iceland chose not to go the zombie way with its failing banks, the difficulties of winding down international banks became apparent even with the country’s financial institutions that were relatively small on a global or regional scale. At their peak in 2008, the largest Icelandic banks’ assets added up to one-fifth of Commerzbank’s, Germany’s second largest bank. Yet the controversy over the government’s decision not to guarantee deposits that the Icelandic banks had collected in other countries is an unresolved dispute between Iceland, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands three years later. The liquidation of Lehman Brothers, which was roughly the size of Commerzbank when it filed for bankruptcy, has revealed even more reasons why the world needs an international bank resolution mechanism. Some 50 bankruptcy proceedings around the world are trying to sort out the assets and liabilities that were scattered among 2,000 legal entities that made up Lehman.

The world’s banks have become more and more international; the global giants operate in every country and even midsize ones function in multiple countries. But the regulatory regimes haven’t kept up with the banks’ globalization. Banking sector supervisors are still national in structure and perspective. Although a supposedly global capital regime exists under the aegis of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the latest round of decision making there showed once again that national interests divide its member countries. The Basel talks in 2010 and 2011 turned into trade negotiations as each member tried to protect its banks’ interests.3 In fact, regardless of where they’re based, most of the largest conglomerates are active everywhere and aren’t really just one country’s problem. When the U.S. government rescued American International Group (AIG) to prevent the collapse of banks that had dumped risk onto the insurance firm, it ended up saving French and German banks as well. Another case in point is the scuttle between U.S. and U.K. governments during the last days of Lehman Brothers. London-based Barclays had emerged as a buyer, but the deal needed a temporary government backing until Barclays shareholders gave their approval for the acquisition. The Americans wanted the British to do it, but the British didn’t want to take risks for rescuing a U.S. institution.4 Consequently, the deal fell through, but it was to the detriment of the global financial system, not just the United States.

The EU, whose banks were encouraged to go across borders and did so, established a continent-wide banking regulator in 2011, but the first impressions of its authority in the region weren’t very encouraging. Given the task of carrying out the stress tests of the largest EU banks, the new supervisor came under pressure from national regulators, having to bend the standards to their demands and delay publication of the results in mid-2011 as the infighting went on.5 “Will the new EU regulator have teeth?” asks Ronán Lyons, an Irish economist. “The European Central Bank has teeth on monetary issues, but when it comes to financial stability, even it has backed off. So it’s hard to see how the new supervisor will win the power.” Basel committee and the Financial Stability Board, which adds the finance ministers of the Group of 20 (G-20) nations to the mix of regulators and central bankers that Basel already has, have been discussing a cross-border resolution mechanism since 2009. However, the issue has proven the toughest on which to reach common ground, members of both groups say.

The difficulty of finding common ground on that issue comes down to burden sharing: When a cross-border financial firm goes down, is taken over, and wound down, who bears the costs? If the firm is global, can the costs be shared among jurisdictions? Member countries don’t want to establish such a burden-sharing scheme. Another hurdle to an international resolution regime is that nobody wants to cede their courts’ authority over bankruptcies to a central mechanism or to some other country’s courts. Instead we have the Lehman situation: dozens of bankruptcy procedures all haggling over assets that don’t have nationalities. The G-20 leaders need to make this a priority. If global trade can have the World Trade Organization, it can also have a supranational banking supervisor and cross-border resolution regime.

The Dodd-Frank reform expanded the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC) powers to take over bank-holding companies —the parent firms to the deposit-insured banks—in an effort to tackle this problem. Former Treasury Secretary Paulson and others have argued that the government lacked the authority to seize Citigroup or Lehman Brothers even if it wanted to. The new mechanism also requires the largest U.S. bank holding companies to present to regulators blueprints for how they’d be wound down in case of failure. If the regulators aren’t satisfied with these plans, they could ask a conglomerate to shed assets and shrink. In theory, this sounds promising, but in practice it’s riddled with the influence politics will play on such decisions. Many observers, such as Columbia University’s Stiglitz, say the new mechanism will be useless because it wasn’t the lack of legal authority that prevented action during the latest crisis; it was lack of willpower on behalf of the regulators and politicians. Even the FDIC’s outgoing chairman, who pushed for the expanded powers, acknowledges that regulators are traditionally reluctant to use such authority when necessary. “We have the tools; it’ll be important to use them,” says Sheila Bair. In a review of the new U.S. regulations, Standard & Poor’s rating agency concluded that the authorities may still choose to bail out a too-big-to-fail (TBTF) firm instead of letting it fail.6 Bair also admits that it would still be tough for the FDIC to wind down an international finance giant and emphasizes the need for establishing a cross-border resolution mechanism.

The Fallacy Over Capital

While an international resolution regime will help deal with failed banks before they turn into zombies, there’s also a strong need for better rules to prevent financial institutions from getting to that point. The best deterrent is a strong capital buffer. Today’s business of banking is a risky endeavor, so the stakeholders should know and share that risk, instead of unknowing taxpayers who end up with footing the bill when the bets go sour. Debt might have been a cheaper way to fund banks, but it has clearly been wrongly priced, ignoring the risk of blowup. That cost is still being kept down because there’s too strong of an implicit backing by governments around the world for too many banks, not even the largest, as we saw in the previous chapter. Forcing the banks, especially the bigger or the more interconnected ones, to have much bigger capital ratios is the only way to shift the risk from the taxpayers’ shoulders to the stakeholders of the banks. If a bank takes too much risk and blows up, its shareholders lose the capital they put in. Banks’ creditors don’t panic and run for the exits. Although a lot of people share these views—including Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, who has advocated higher capital standards7—there are many nuances when it comes to capital regulation.

Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers had enough capital according to their regulators the week before they went down. How could that be? Global capital standards were fundamentally overhauled in 2004, basing them on the banks’ own calculations of their assets’ risks.8 In other words, banks come up with sophisticated formulas of how risky the loans, bonds, or other components of their balance sheets are, and the capital requirement is calculated based on that. A bank could have $400 billion of assets, but it could hold as little as $10 billion in capital. That capital didn’t have to be stocks either; it could be made up of hybrid bonds that were treated as equity for regulatory purposes. That’s 40 times leverage: if your assets lose 3 percent of their value, your capital is wiped out. No wonder banks could go under so easily during the latest crisis.

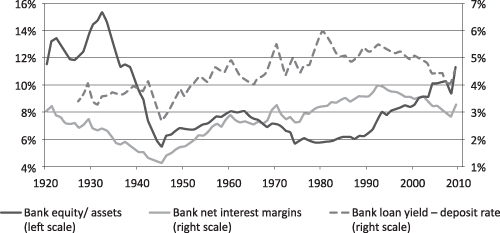

Despite the improvements in the ratios and definitions of capital under Basel III, what has been done is not nearly enough. The capital ratio has been increased to 7 percent for common stock (though some other things can still be counted in the numerator) from 2 percent, and the largest global banks may face another 2.5 percent on top of that. But the safe ratio is more like 20 percent, as Switzerland has done, though the Swiss allow the new hybrid concoctions called contingent capital in the mix. The 20 percent would provide the buffer to the kind of losses that were experienced in the 2008 meltdown, argues Council on Foreign Relations fellow Sebastian Mallaby.9 Banks scream bloody murder at such suggestions though, arguing that it would increase the cost of capital and hurt lending to the economy. Studies show that a bigger share of equity in the banks’ funding mix has negligible impact on lending rates and doesn’t restrict credit (Figure 11.1).10 Equity is more expensive for banks now because they have so little of it and the risk of being wiped out as a shareholder is so great. If that risk went down, equity would be cheaper. Debt has been priced lower than it should be because of implicit government backing for the bigger banks. It would go up if that support is lifted, but also come down if there’s enough of an equity buffer to protect bondholders. Bank executives resist equity because their pay packages are tied to stock performance. So dilution of stock—even if it happens once to bring them up to a 20 percent level now—would hurt their pay for a year or two. However, after the initial adjustment, there’s no reason bank stocks shouldn’t perform well in the long run. This type of safety doesn’t prevent them from making profits.

Figure 11.1 Research has shown that there’s no significant relationship between loan spreads and bank-equity levels.

SOURCE: Samuel G. Hanson, Anil K. Kashyap, and Jeremy C. Stein, “A Macroprudential Approach to Financial Regulation,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 25, no. 1 (Winter 2011), 3–28.

To avoid the gaming of the risk measurement that capital regulations still depend on, the simple leverage ratio, which ignores risk all together and just looks at the face value of assets, needs to be used more widely and strictly, as FDIC’s Bair has argued for half a decade. Max Planck Institute’s Martin Hellwig argues that the measurability of risk is an illusion and thus risk-based capital regulation is doomed to fail.11 “Harsh simple leverage ratio tells you where to look for problems and then you go examine the bank,” says Hoenig, who headed the Kansas City Fed’s bank supervision unit for a decade before becoming its president. For the leverage ratio to be truly effective, banks’ off-balance-sheet assets and derivatives need to be counted in as well. The use of a global leverage ratio has already come under attack in Europe though and might not get implemented.

Inclusion of hybrid securities or other assets, such as mortgage-servicing rights, in the calculation of the most basic capital—as still maintained in Basel rules—will also weaken the effectiveness of the buffer. Bair, Hoenig, and others have voiced doubt on how well the newly formulated contingent capital—where some bonds with pre-agreed triggers convert to stock in times of financial trouble—would work. The United States had a similar product called Trust Preferred Securities used widely by its banks prior to the crisis, but those proved not to provide the security needed.12 Conversion of the contingent bonds to stock could wreak havoc for the bank, showing its weakness and the weakness of the sector, critics say.

Breaking Up the Big Boys

Even if they’re not zombies right now, the biggest global banks are in danger of becoming zombies in the next crisis or the one after that because they’re too big to fail and too big to manage. The EU has forced some to break up after the 2008 crisis if they received substantial government support. The U.S. financial reform includes a cap on one bank’s share of the nation’s total deposits, which could prevent the four biggest from getting even larger. The United Kingdom toyed with the idea of some forceful breakup, but it didn’t have the political guts to do it at the end. Switzerland is trying to force the separation of the investment bank arm of UBS, the country’s largest lender, and its relocation to the United States. None of these countries have been able to come close to the 1933 U.S. decision that was taken despite strong opposition from the finance industry, which forced the separation of investment and commercial banking. Glass-Steagall’s revival (and its adoption in Europe as well) would be one way to divide the TBTF institutions, but it’s not the only way. Governments could just place strict size limitations on banks (such as the proposed legislation by U.S. senators Sherrod Brown and Ted Kaufman would do) and force the top banks to split up. To avoid the migration of all the risk to nonregulated financial institutions, such as hedge funds, even harsher size caps should be placed on nonbank players in financial markets so they can never get to the size that’s TBTF.

Bankers argue consistently that the big, international, one-stop-shop conglomerates are needed for the global economy. Citigroup officials argued during the crisis that, if they were allowed to fail, U.S. and other western companies couldn’t send money around the world and global trade would be disrupted. Academic research shows that the economies of scale for banking max out at about $100 billion of assets.13 That is less than one-twentieth the size of Citi or any other global player. Moving money around the world for payments, though carried out by banks, is a utility that could be shifted to a global nonprofit organization. Technology has made such transfers simpler and removed the need for any one entity to be physically present in a location to enable the transmission. In underbanked African countries, mobile phones are being used to make money transfers. “It’s not the size but the complexity of today’s largest banks that render them impossible to manage,” says Paul Miller, head of financial services research at FBR Capital Markets. “Citi and Bank of America are so widespread, so complicated, how can any management team do a good job?” If a bank just stuck to the traditional business of collecting deposits and making loans, size wouldn’t be an issue, but in today’s banking, the model has evolved too much. Miller refuses to cover Citi for his clients because the majority of its operations are outside the U.S., spread out to more than a hundred countries, with way too many different financial, economic, and political factors to consider when evaluating the bank’s businesses. “Same goes for the management: how can they know what’s happening in all those places?” says Miller.

Miller thinks the largest banks will be forced to break up slowly in the next decade because investors will demand lenders to be more focused and on more solid ground with what they do. The new regulations, from Basel to Dodd-Frank, will also help apply pressure to that effect, according to Miller. The stricter rules could undermine the universal banking model, according to Goldman Sachs analysts. The biggest banks might consider exiting certain businesses, Goldman said in a research note in June 2011.14 If Miller and the Goldman analysts are right, the necessary breakup of TBTF institutions will happen through a back-door way and in slow motion. Let’s hope another crisis doesn’t break out before then.

Coming to Terms with Reality

As is the case with most financial crises, the problems of the banks are closely associated with the debt overhang society faces after a decade or two of binging on cheap credit. So the solution once again lies in the realization that we need to restructure those debts before we can shake off the problems and move beyond the latest crisis. Sooner or later, policymakers come to terms with that reality in each financial disaster and the restructuring takes place. But as we’ve also seen from past experience, delaying the inevitable leads to years of economic stagnation and increased costs in the end.

In the United States, household debt needs to be restructured, particularly the millions of underwater mortgages, where the market value of the home is way below the outstanding loan on the property. While system-wide principal reductions by the banks are necessary, they can be carried out in a way to minimize the moral hazard such restructuring could create among consumers. Many homeowners who can actually afford their payments could opt for so-called strategic default if they saw widespread use of principal forgiveness. To prevent that from happening, there could be several disincentives put in place, argues Amherst Securities’ Laurie Goodman. One of those disincentives would be taxing heavily the future appreciation of the home’s value or forcing the homeowner to share that increase with the bank forgiving the principal, Goodman suggests.15 Along with principal reductions, foreclosures need to happen at a faster pace too. Not every homeowner can afford to stay in his home even after his debt is reduced significantly. Those houses need to be foreclosed and put on the market quickly. If prices are to drop further, the faster that happens, the quicker the rebound can start. Since the nation’s legal system is overwhelmed with foreclosures and the incomplete paperwork presented by the banks to carry them out, Congress could aid with some fast rules that would overlook the insufficiencies in exchange for serious capital reductions by the banks as well. This is part of what Elizabeth Warren was trying to achieve with her proposed solution to mortgage-servicing problems that was thwarted by the banks, the Fed, and some attorneys general.

In Europe, the overwhelming debt is on the shoulders of several periphery countries. Regardless of the different ways they got there, Greece, Ireland, and Portugal owe too much to be paid back. The restructuring of their debt, if done in an organized fashion and in coordination with fixing Spain’s problems, can help the EU avoid the collapse of its monetary union. This would require Germany, France, and other EU countries to face the specter of their weak zombie banks falling apart; they need to handle the crisis the way Sweden did in the 1990s. To avoid falling into the same category as Greece, Ireland, and Portugal, Spain also needs to shutter its zombies, forcing their creditors to bear the costs so that the burden doesn’t fall on the Spanish taxpayers when the country’s debt is at such a critical level. That will again impact other EU banks who’ve lent to the Spanish cajas. The EU, just like the United States, needs to face reality and stop protecting its weak banks if it wants to salvage its future.

Notes

1. Urban Bäckström, “What Lessons Can be Learned from Recent Financial Crises? The Swedish Experience,” Speech given by Swedish central bank governor, August 29, 1997; Anthony M. Santomero and Paul Hoffman, “Problem Bank Resolution: Evaluating the Options,” paper presented at the Annual Financial Management Association Meetings, October 15–17, 1998.

2. Jana Randow and Simon Kennedy, “Ireland Opens New Front as ECB Battles to Avert Meltdown,” Bloomberg News, June 16, 2011; Carmel Crimmins, “Interview—Bondholders Seek Bank of Ireland Rights Issue,” Reuters, June 10, 2011.

3. Yalman Onaran, “German Push to Delay Basel Capital Rules Meets U.S. Opposition,” Bloomberg News, September 9, 2010; Yalman Onaran and Simon Clark, “European Banks Poised to Win Reprieve in Basel on Capital Rules,” Bloomberg News, July 12, 2010; Yalman Onaran, “Banks Best Basel as Regulators Dilute or Delay Capital Rules,” Bloomberg News, December 21, 2010; Jim Brunsden, “Basel Said to Weigh 3.5 Percentage-Point Fee Based on Bank Size,” Bloomberg News, June 16, 2011; Brooke Masters and Patrick Jenkins, “Biggest Banks Face New Capital Clampdown,” Financial Times, June 17, 2011.

4. Yalman Onaran and John Helyar, “Lehman’s Last Days” Bloomberg Markets, January 2009, 50–62.

5. Karin Matussek and Ben Moshinsky, “Bafin’s Sanio Criticizes EU Regulator Over Bank Stress Tests,” Bloomberg News, June 6, 2011; David Enrich, “Europe’s Stress Tests to Be Delayed,” Wall Street Journal, June 2, 2011.

6. Rodrigo Quintanilla, Matthew Albrecht, Brendan Browne, “The U.S. Government Says Support for Banks Will Be Different ‘Next Time’—But Will It?” Standard & Poor’s Ratings Direct, July 12, 2011.

7. Damian Paletta, “Geithner Pushes for Tough Global Capital Rules,” Wall Street Journal, September 3, 2009.

8. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework,” published by Bank for International Settlements, June 2004; Daniel K. Tarullo, Banking on Basel: The Future of the International Financial Regulation (Washington, DC: Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2008).

9. Sebastian Mallaby, “The Radicals Are Right to Take on the Banks,” Financial Times, June 8, 2011.

10. Samuel G. Hanson, Anil K. Kashyap, and Jeremy C. Stein, “A Macroprudential Approach to Financial Regulation.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 25, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 3–28; Anat R. Admati, Peter M. DeMarzo, Martin F. Hellwig, and Paul C. Pfleiderer, “Fallacies, Irrelevant Facts, and Myths in the Discussion of Capital Regulation: Why Bank Equity Is Not Expensive,” Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University Working Paper No. 86, March 23, 2011.

11. Martin Hellwig, “Capital Regulation after the Crisis: Business as Usual?” CESifo DICE Report 8, no. 2 (2010): 40–46.

12. Yalman Onaran and Jody Shenn, “Banks in ‘Downward Spiral’ Buying Capital in Discredited CDOs,” Bloomberg News, June 8, 2010.

13. Ötker-Robe, Narain, Ilyina, and Surti, “The Too-Important-to-Fail Conundrum.”

14. Richard Ramsden, Ryan Nash, Christopher M. Neczypor, and Alexander Blostein, “United States: Banks—Finding Relative Winners in a Post SIFI-World,” Goldman Sachs & Co. analyst report, June 17, 2011.

15. For more measures to deter strategic defaults, see Laurie Goodman, Roger Ashworth, Brian Landy, and Lidan Yang, “The Case for Principal Reductions,” Amherst Securities Group LP research report, March 24, 2011.