Fighting for the Rights Due All Americans: The Road to the March

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. first became enamored of the life and efforts of Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent marches to achieve humane objectives through passive resistance when he was getting his divinity degree at Crozer Theological Seminary. He had already obtained a degree from Morehouse College at the age of 19 and would hold a Ph.D. from Boston University by 1955.

Born to parents who were by anyone’s standards well off, he could have chosen a number of paths in life, yet he would take the one where he would be arrested, where crowds he led would be set on by police, dogs, and fire hoses, by jeers and rocks thrown by hostile mobs, and by bombs set in churches that even took the lives of children.

King’s first encounter with a racial crisis happened in Montgomery, Alabama, where he was pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Tension had been mounting over the local transit company’s policy of segregated public buses when civil rights activist Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white man. Elected president of the Montgomery Improvement Association, which was organized to boycott the transit company, King’s now famous initial stated principal was, “We will not resort to violence. We will not degrade ourselves with hatred. Love will be returned for hate.” A one-day boycott turned into a much longer one when resistance in the form of intimidation, threats, mass arrests, and even physical violence only strengthened the resolve of the boycotters to stay nonviolent themselves.

The result came a year later when the Supreme Court ruled Alabama’s segregated bus policy to be unconstitutional. People of all races rode the buses together, all from a well-organized, successful nonviolent effort.

A movie theater sign in Birmingham, a city that had a well-deserved reputation as the most segregated and racially violent city in the deep South. Its long string of unsolved racist bombings, many attributed to the KKK, earned the city the epithet Bombingham. 1963.

With that template in mind, King, along with Ralph Abernathy and other civil rights activists, organized the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957. King served as the group’s first president, and the SCLC moved from Montgomery, Alabama, to Atlanta, Georgia, when King became associate pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Rosa Parks and her husband, Raymond, would both lose their jobs over the Montgomery bus incident but, when they moved to Detroit, Rosa remained an active worker for both the NAACP and the SCLC.

These were contentious times, with tension almost always beneath the surface. Awareness was ever growing, but the resistance to civil rights was often vigorous, even harsh. The times were defined by Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, published in 1952, that addressed many of the social and intellectual issues facing African Americans early in the twentieth century, how African Americans continued to be treated as a subculture that was nearly invisible to whites. The Voting Rights Act would be brought before Congress five times in the 1950s, only to be defeated each time by southern Democrats, led by Texans Sam Rayburn and Lyndon B. Johnson.

The tension and unrest continued to grow, yet Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. stayed true to his intention to make change peacefully. In 1959 he published a short book called The Measure of a Man, which contained his sermons like, “What Is Man?” and “The Dimensions of a Complete Life.” The sermons balanced an argument for man’s need for God’s love and criticized the racial injustices of Western civilization.

The King-encouraged peaceful approach led to the Freedom Riders, civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated southern United States from 1961 and later to challenge the nonenforcement of the U.S. Supreme Court decisions of Irene Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia (1946) and Boyton v. Virginia (1960), which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional. The southern states had ignored the rulings, and the federal government had done nothing to enforce them. The first Freedom Ride left Washington, D.C., on May 4, 1961 and was scheduled to arrive in New Orleans on May 17.

In 1961, a desegregation coalition formed in Albany, Georgia, and became known as the Albany Movement. In December of that year, Martin Luther King, Jr. and the SCLC became involved. The movement mobilized thousands of citizens for a nonviolent confrontation on every aspect of segregation within the city and attracted nationwide attention. When King first visited on December 15, 1961, he had planned to stay a day or so and return home. The following day he got swept up in a mass arrest of peaceful demonstrators. To leverage the point being made, he declined bail until the city made concessions.

In April 1963, the SCLC began its campaign against racial segregation and economic injustice in Birmingham, Alabama. The campaign again used nonviolent but intentionally confrontational tactics, developed in part by Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker. Black people in Birmingham, along with members of the SCLC, occupied public spaces with marches and sit-ins, openly violating laws that they considered unjust.

During a mass meeting at the 16th Street Baptist Church, King urges his supporters to join the demonstrations. Birmingham, Alabama. 1963.

Not all that far away in Jackson, Mississippi, on June 12, 1963, a Mississippi desegregation leader, Medgar Evans, was killed by gunfire.

On June 11, 1963, John F. Kennedy called for a Civil Rights Act in his civil rights speech, in which he asked for legislation “giving all Americans the right to be served in facilities which are open to the public—hotels, restaurants, theaters, retail stores, and similar establishments,” as well as “greater protection for the right to vote.” Kennedy delivered this speech following a series of protests from the African American community, the most recent being the Birmingham campaign, which had concluded in May 1963.

Looking back, historically, these were small nonviolent successes, practice sessions for something far bigger and grander that was about to take place.

An eloquent speaker to his congregation at the 16th Street Baptist Church, King convinced many to help demonstrate. Birmingham, Alabama. 1963.

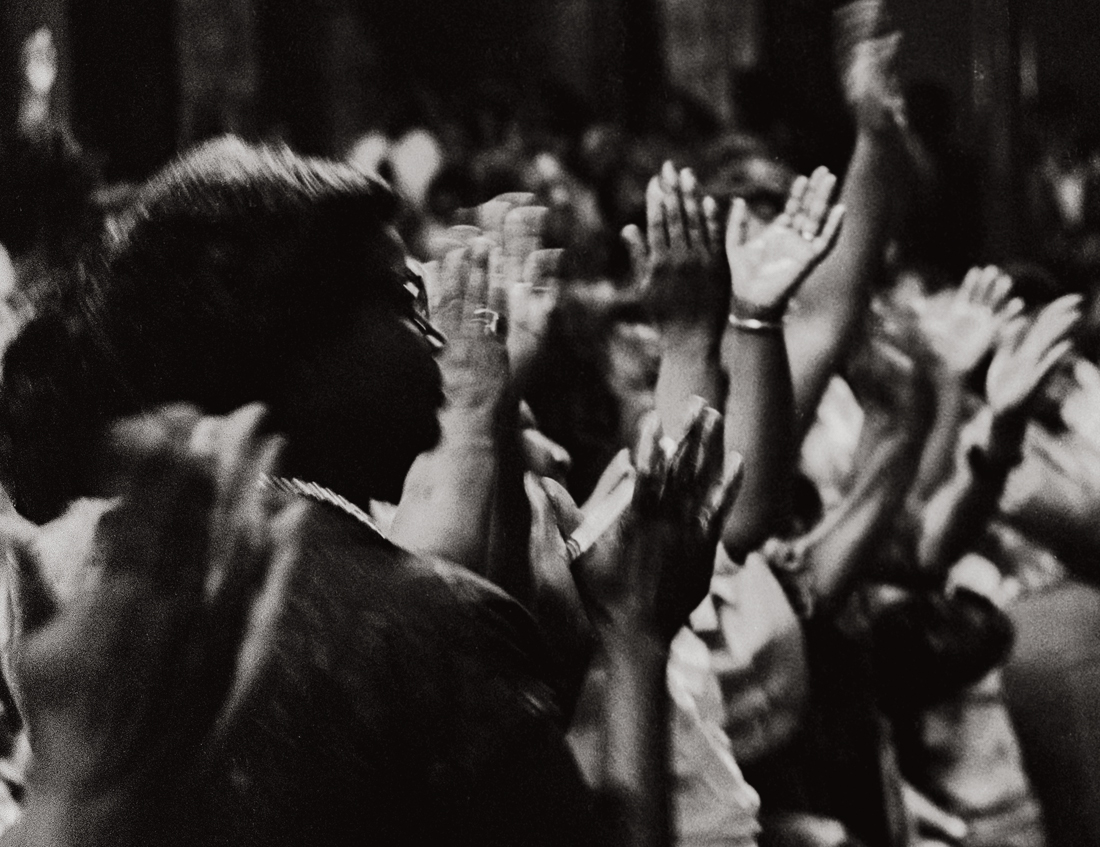

An enthusiastic response by the audience at the mass rally at the 16th Street Baptist Church. Birmingham, Alabama. 1963.

King knew how to touch the hearts of his audience at the mass rally at the 16th Street Baptist Church. Birmingham, Alabama. 1963.

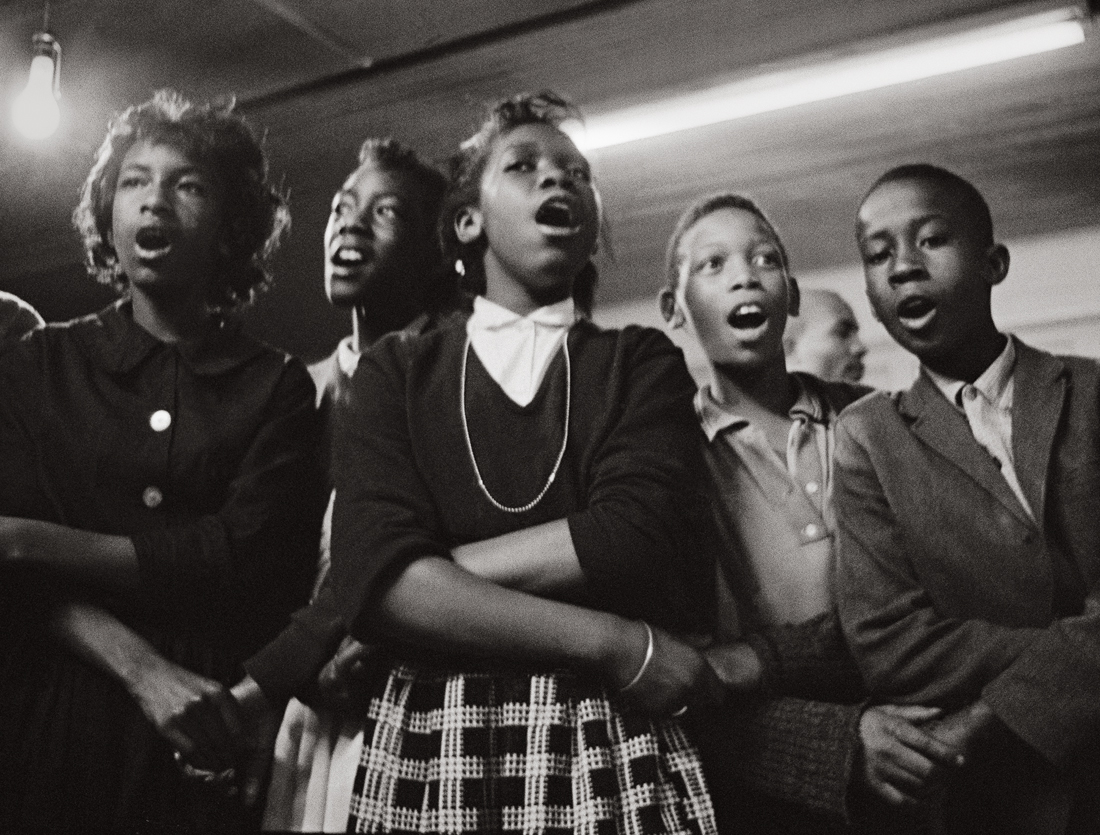

In the 16th Street Baptist Church, children crusaders link hands and sing, “We shall overcome” prior to the demonstration. Birmingham, Alabama. June 1963.

Concerned young people at the planning session for the Children’s Crusade in the basement of the 16th Street Baptist Church. Birmingham, Alabama. June 1963.

The Children’s Crusade. The police had contained the demonstrations to the black part of town. But by filling the jails, the protestors immobilized the police—and the next wave of demonstrators could peacefully protest for the first time in downtown Birmingham. The jails were flooded, the city was paralyzed, and the white leadership realized it had to come to the bargaining table. 1963.

Arrested Children’s Crusaders are placed on school buses as a massive number of demonstrators are sent off to be detained in the Birmingham Athletic Field. June 1963.

Improvised prisons: High school student demonstrators are detained in a sports stadium. Birmingham, Alabama. June 1963.

A picketer under arrest behind Loveman’s department store. The protest focused on segregation and unfair hiring practices. Birmingham was a turning point. It was the first time the Movement took on such a large city. King called it the most segregated city in America. June 1963.

Demonstrators hold on to one another to face the full force of the fire hoses that peeled the bark off the trees in Kelly Ingram Park. Birmingham, Alabama. June 1963.

No man is an island. The police and firemen used a brute show of force to try to stop the ongoing demonstrations. It didn’t work. Rather than fleeing, the protestors hung onto each other and were able to stand up to the full fury of the water, though not without casualties. As Dr. King later said, “I am startled that out of so much pain some beauty came.” Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, Alabama. June 1963.