The Aftermath: 1963–April 4, 1968

The March on Washington of 1963 was followed by more years of racial strife. Yet a strong seed had been sown of affirmation, of hope, of belief in the democratic process, and of faith in the capacity of blacks and whites to work together for racial equality.

The Civil Rights Act

One momentous event that followed the march and benefited the civil rights movement was the Civil Rights Act that was enacted on July 2, 1964. It outlawed major forms of discrimination against racial, ethnic, national, and religious minorities, and women. The bill had been earlier called for by the now-late President John F. Kennedy in his June 11, 1963 civil rights speech but was signed into law by Lyndon B. Johnson, who had once opposed voting rights for African Americans. Many credit the public demonstration of the march with making it clear that the tide had turned. The Act made it through Congress in spite of a 54-hour filibuster by southern congressmen from both parties. The opposition came from such congressmen as Strom Thurmond, Evert Dirksen, and Hubert Humphrey.

Lyndon B. Johnson, once an opponent but a consummate politician and now someone who could sense the change in the nation, told the legislators, “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory than the earliest possible passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long.”

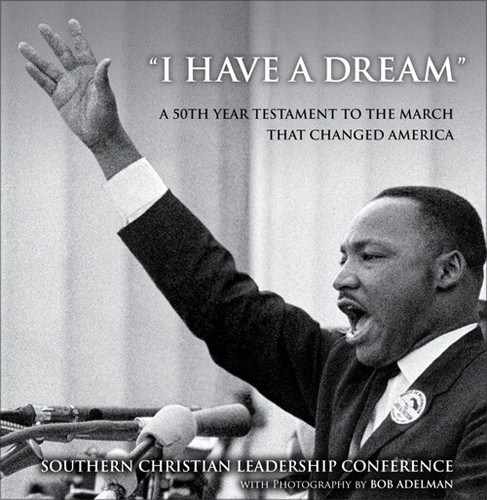

For the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), it was a step forward but also the beginning of a long campaign to continue to strive for civil rights for African Americans. In 1964, King and the SCLC were the driving forces behind intense demonstrations in St. Augustine, Florida. The movement marched nightly through the city and experienced violent attacks from white supremacists. Hundreds of the marchers were arrested and jailed.

These efforts did not go unnoticed. On October 14, 1964, Martin Luther King, Jr. received the Nobel Peace Prize for combating racial inequality through nonviolence.

In December 1964, King and the SCLC joined forces with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Selma, Alabama, where the SNCC had been working on voter registration for several months. A local judge issued an injunction that barred any gathering of three or more people affiliated with the SNCC, SCLC, DCVL, or any of 41 named civil rights leaders. This injunction temporarily halted civil rights activity until King openly defied it by speaking at Brown Chapel on January 2, 1965.

Next came the Selma to Montgomery marches. On March 7, 1965, King, James Bevel, and the SCLC, again in partial collaboration with the SNCC, attempted to organize a march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. The first attempt to march on that Sunday in March was aborted because of mob and police violence against the demonstrators. Six hundred marchers had assembled and planned to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge over the Alabama River en route to Montgomery. Just short of the bridge, they found their way blocked by Alabama State Troopers and local police, who ordered them to turn around. When the protestors refused, the officers shot teargas and waded into the crowd, beating the nonviolent protestors with billy clubs. More than fifty of the peaceful demonstrators had to be hospitalized. This day has since become known as Bloody Sunday.

Bloody Sunday was a major turning point in the effort to gain public support for the civil rights movement, the clearest demonstration up to that time of the dramatic potential of King’s nonviolence strategy. King, however, was not present.

King had met with officials in the Johnson administration on March 5 to request an injunction against any prosecution of the demonstrators. He did not attend the march due to church duties, but he later wrote, “If I had any idea that the state troopers would use the kind of brutality they did, I would have felt compelled to give up my church duties altogether to lead the line.” Footage of police brutality against the protestors was broadcast extensively and aroused national public outrage.

King next attempted to organize a march for March 9. The SCLC petitioned for an injunction in federal court against the State of Alabama, which was denied. The judge issued an order blocking the march until after a hearing. Nonetheless, King led marchers on March 9 to the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. Then he held a short prayer session before turning the marchers around and asking them to disperse so as not to violate the court order. The unexpected ending of this second march aroused the surprise and anger of many within the local movement. The march finally went ahead fully on March 25, 1965. At the conclusion of the march on the steps of the state capital, King delivered a speech that became known as “How Long, Not Long.” In it, King stated that equal rights for African Americans could not be far away, “because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

The Voting Rights Act

On August 6, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law. In the Oval Office watching him sign were Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and other civil rights leaders. This was another big step many feel could not have happened without the march.

The Voting Rights Act outlawed the sort of discriminatory practices, such as the literacy tests used in southern states, that had kept many African Americans from voting.

The Act was sent to Congress by President Johnson on March 17, 1965. The bill passed the Senate on May 26, 1965. The House was slower to give its approval. After five weeks of debate, it was finally passed on July 9. After differences between the two bills were resolved in conference, the House passed the Conference Report on August 3 and the Senate followed on August 4. On August 6, President Johnson signed the Act into law.

By 1965, concerted efforts to break the grip of state unequal treatment of minorities had been under way for some time but had achieved only modest success overall and in some areas had proved almost entirely ineffectual. The murder of voting-rights activists in Philadelphia, Missouri, gained national attention, along with numerous other acts of violence and terrorism.

It was that unprovoked attack by state troopers on peaceful marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on their way to the state capitol in Montgomery, that persuaded the president and Congress to overcome southern legislators’ resistance to effective voting rights legislation.

Congress determined that the existing federal antidiscrimination laws were insufficient to overcome the resistance by state officials to enforcement of the Fifteenth Amendment. The legislative hearings showed that the Department of Justice’s efforts to eliminate discriminatory election practices by litigation on a case-by-case basis had been unsuccessful in opening the registration process; as soon as one discriminatory practice or procedure was proven to be unconstitutional and enjoined, a new one would be substituted in its place and litigation would have to commence anew.

Soon after passage of the Voting Rights Act, federal examiners were conducting voter registration checks and found that black voter registration had begun a sharp increase. The cumulative effect of the Supreme Court’s decisions, Congress’s enactment of voting rights legislation, and the ongoing efforts of concerned private citizens and the Department of Justice had been to restore the right to vote guaranteed by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

The Voting Rights Act itself has been called the single most effective piece of civil rights legislation ever passed by Congress.4

Ongoing SCLC Activities

When the Meredith, Mississippi, “March Against Fear” passed through Grenada, Mississippi, on June 15, 1966, it sparked months of civil rights activity on the part of Grenada blacks. They formed the Grenada County Freedom Movement (GCFM) as an SCLC affiliate, and within days they had 1,300 blacks registered to vote.

Although the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had outlawed segregation of public facilities, the law had not been applied in Grenada, which still maintained rigid segregation. After black students were arrested for trying to sit downstairs in the “white” section of the movie theater, the SCLC and the GCFM demanded that all forms of segregation be eliminated. They called for a boycott of white merchants. Over the summer, the number of protests increased, and many demonstrators and SCLC organizers were arrested as police enforced the old Jim Crow social order. In July and August, large mobs of white segregationists mobilized by the KKK violently attacked peaceful marchers and news reporters with rocks, bottles, baseball bats, and steel pipes.

When the new school year began in September, the SCLC and the GCFM encouraged more than 450 black students to register at the formerly white schools under a court desegregation order. This was by far the largest school integration attempt in Mississippi since the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954. The all-white school board of Grenada County resisted fiercely. Whites threatened black parents with economic retaliation if they did not withdraw their children, and by the first day of school the number of black children registered in the white schools had dropped to approximately 250. On the first day of class, September 12, a furious white mob organized by the KKK attacked the black children and their parents with clubs, chains, whips, and pipes as they walked to school, injuring many and hospitalizing several with broken bones. Police and Mississippi State Troopers made no effort to halt or deter the mob violence.

Over the following days, white mobs continued to attack the black children until public pressure and a federal court order finally forced Mississippi lawmen to intervene. By the end of the first week, many black parents had withdrawn their children from the white schools out of fear for their safety, but approximately 150 black students continued to attend, the largest school integration in state history at that point in time.

Inside the schools, blacks were harassed by white teachers, threatened and attacked by white students, and expelled on flimsy pretexts by school officials. By mid-October, the number of blacks attending the white schools had dropped to roughly 70. When school officials refused to meet with a delegation of black parents, black students began boycotting both the white and the black schools in protest. Many children, parents, GCFM activists, and SCLC organizers were arrested for protesting the school situation. By the end of October, almost all of the 2,600 black students in Grenada County were boycotting school. The boycott did not end until early November when SCLC attorneys were granted a federal court order that the school system must treat everyone equal regardless of race and meet with black parents.

After several successes in the South, King and others in the civil rights organizations sought to spread the movement to the North later in 1966. King and Ralph Abernathy, both from the middle class, moved into a building at 1550 South Hamlin Avenue, in the slums of North Lawndale on the west side of Chicago, as an educational experience and to demonstrate their support and empathy for the poor.

The SCLC formed a coalition with the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO), an organization founded by Albert Raby. The combined organizations’ efforts were supported by The Chicago Freedom Movement. During that spring, several tests of real estate offices revealed racial steering: the discriminatory processing of housing requests made by couples who were exact matches in income, background, number of children, and other attributes where white couples were favored over black couples. Several larger marches were planned and executed in Bogan, Belmont Cragin, Jefferson Park, Evergreen Park (a suburb southwest of Chicago), Gage Park, and Marquette Park.

Abernathy said that the movement received a worse reception in Chicago than in the South. Marches, especially the one through Marquette Park on August 5, 1966, were met by bottles thrown by screaming throngs. Rioting seemed very possible. King, as always, remained opposed to staging a violent event, or one that could become violent. He negotiated an agreement with Mayor Richard J. Daly to cancel one march to avoid the violence that he feared would result. King was hit by a brick during another march yet continued to lead marches in the face of personal danger.

When King and his supporters returned to the South, they left Jesse Jackson, a seminary student who had previously joined the movement in the South, in charge of their organization. Jackson continued their struggle for civil rights by organizing the Operation Breadbasket movement that targeted chain stores that did not deal fairly with blacks.

In an April 4, 1967 appearance at the New York City Riverside Church—exactly one year before his death—King delivered a speech entitled “Beyond Vietnam.” He spoke against the U.S. role in the war, arguing that the United States was in Vietnam “to occupy it as an American colony.” He called the U.S. government “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” King also opposed the Vietnam War because it took money and resources that could have been spent on social welfare at home. Congress was spending more and more on the military and less and less on antipoverty programs.

Eldridge Cleaver’s post-prison book Soul on Ice was published in 1968. A central premise of the book was the trouble of identification as a black soul that has been “colonized” by an oppressive white society.

In 1968, King and the SCLC organized the “Poor People’s Campaign” to continue to address issues of economic justice. King traveled the country to assemble “a multiracial army of the poor” that would march on Washington to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience at the Capitol until Congress created an “economic bill of rights” for poor Americans. The campaign culminated in a march on Washington, D.C., demanding economic aid to the poorest communities of the United States.

King and the SCLC called on the government to invest in rebuilding America’s cities. He felt that Congress had shown “hostility to the poor” by spending “military funds with alacrity and generosity.” He contrasted this with the situation faced by poor Americans, claiming that Congress had merely provided “poverty funds with miserliness.” His vision was for change that was more revolutionary than mere reform: he cited systematic flaws of “racism, poverty, militarism, and materialism,” and argued that “reconstruction of society itself is the real issue to be faced.”

The Poor People’s Campaign was controversial even within the civil rights movement. Bayard Rustin resigned from it stating that the goals of the campaign were too broad and the demands unrealizable. He thought that these campaigns would accelerate the backlash and repression on the poor and the black.

The Day the King Fell

On April 4, 1968 at 6:01 p.m. a shot rang out as Martin Luther King, Jr. stood on the Lorraine Motel’s second-floor balcony in Memphis. He was pronounced dead at St. Joseph’s Hospital. Two months after King’s death, escaped convict James Earl Ray was captured at London’s Heathrow Airport while trying to leave the United Kingdom on a false Canadian passport in the name of Ramon George Sneyd, on his way to white-ruled Rhodesia. Ray was quickly extradited to Tennessee and charged with King’s murder. He confessed to the assassination on March 10, 1969, although he recanted this confession three days later.

The plan to set up a shantytown in Washington, D.C., was carried out on May 2, 1968, soon after the April 4 assassination. Criticism of King’s plan was subdued in the wake of his death, and the SCLC received an unprecedented wave of donations for the purpose of carrying it out. The campaign officially began in Memphis, on May 2, at the Lorraine Motel where King was murdered. Thousands of demonstrators arrived on the National Mall and established a camp they called “Resurrection City.” They stayed for six weeks.

On October 16, 1968, at the Olympics in Mexico City, African American track and field athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who had won gold and silver medals in the 200-meter race, raised black-gloved fists into the air and held them there during the length of the “Star Spangled Banner.” Smith later said the gesture was not intended as a black power salute but as a human rights salute. The two athletes were expelled from the games.

Although the steps were small, they were sure. The efforts of King, the march, and the SCLC and other organizations increasing pressure for civil rights began to have a measurable effect. For one, in the November 5, 1968 presidential election, 51.4% of registered nonwhites voted, as compared to 44% in 1964, and black registration for voting in 11 southern states rose from 1,463,000 in 1960 to 3,449,000 in 1971. In the years from 1970 to 1973, the black migration that had been trending South to North reversed, and African Americans began moving from the North back to the South, reflecting economic factors.

The SCLC Through the Years That Lay Ahead

Through the years that followed, the SCLC pressed on with its efforts. Following Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s first presidency from 1957–1968, Ralph Abernathy served as president from 1968–1977, Joseph Lowery from 1977–1997, Martin Luther King, III, from 1997–2004, Fred Shuttlesworth in 2004, Charles Kenzie Steele, Jr. from 2004–2009, and Howard W. Creecy, Jr. from 2009–2011. Isaac Newton Farris, Jr. has been serving as president since 2011.

Among the many distinguished members of the SCLC have been Ralph Abernathy, Maya Angelou, Ella Baker, James Bevel, Septima Clark, Dorothy Cotton, Walter E. Fauntroy, Curtis W. Harris, Jesse Jackson, Martin Luther King, III, Joseph Lowery, Diane Nash, James Orange, Fred Shuttlesworth, Charles Kenzie Steele, C.T. Vivian, Hosea Williams, Andrew Young, and Claud Young.