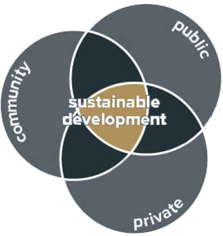

Figure 3.1:

Sustainable development occurs when people are part of the planning and placemaking process

Human beings are naturally collaborative and proactive in creating their own habitats. Most of the world’s population now live in urban environments, and the majority of people want to live in the enterprising and sustainable communities that traditional planning seeks to support and deliver. But professionals and politicians tend to dominate planning and placemaking, which means that communities can become alienated from the process.

Communities are all too often only ‘consulted’ on proposals that have already been formulated without their input, and see themselves as being excluded from the real decision making, which usually takes place before the ‘consultation’ stage even begins. This can lead to poor decisions that ignore local knowledge and needs. Proposals that are not supported by the wider community often lead to opposition campaigns and costly delays in the planning process.

Nicholas Boys Smith, from the London-based urban thinktank Create Streets, highlights research13 that shows a cavernous divide between the professional and the layperson on what is viewed as good and bad architecture. For this reason, he promotes the idea that urban planning and development must acknowledge what people want, because if it is left up to the professional, citizens will continue to live with ill-advised buildings and streetscapes that do not suit their needs and desires.

David Halpern’s 1995 publication, Mental Health and the Built Environment, describes architecture and planning as subjective and lacking the empirical tradition that would make it legible to the scientific eye.14 His book considers several issues that arise when trying to identify and analyse the built environment’s impact on stress, personal relationships and the relationships between the environment’s symbolic elements. From his analyses, it is clear that people experience the built environment in vastly different ways, and that this paradox should be central to placemaking.

Drawing on the disciplines of psychology, neuroscience and urban planning, Charles Montgomery in Happy City describes how cities affect how we think, feel and behave.15 He argues that the green city, the low-carbon city and the happy city are the same thing, and happiness is not just the pleasure of it; it is through being an active member of society that we become happier.

Research published by the Prince’s Foundation in 2014 concluded that: ‘People want where they live to be more than just a building. They want it to be somewhere distinct, somewhere that enhances their quality of life: a place. Creating places goes beyond merely creating spaces – it means designing buildings that cater to the needs of residents, supporting quality public spaces and providing opportunities for communities to thrive.’ It continues: ‘Perhaps above all, communities want to be genuinely involved in a real, not stage-managed, consultation process.’16

The quality and functioning of a city, town or village is critical to the realisation of shared objectives across the political spectrum: local prosperity, economic growth, and access to jobs and training, culture and heritage, social integration and equity, community safety and health and wellbeing. Communities want to have a say, and many want the opportunity to participate in shaping the design and governance of their place so that it reaches its full potential for the people who live and work there.

Full participation, in a properly organised collaborative charrette process, is about incorporating the community’s knowledge into the process, and working with professionals to create better proposals, and therefore better places. Improving the quality of life becomes a shared goal around which a vision of the future and specific projects can then be developed. It provides a way for individuals within the community to offer local expertise, creativity and enthusiasm, and to work with professionals and strangers as well as friends, family and neighbours. Actively engaging communities early in the planning process can result in substantial benefits to economic, environmental and social sustainability.

Charrettes have a key role to play, and the experience and knowledge base built up by practitioners over the past fifty years should be expanded on to develop skills, resources, policies and funding to move charrettes into the mainstream.

Professional and community organisations should:

- Run publicity campaigns to promote the benefits of charrette processes to politicians, local authorities, developers and communities

- Establish programmes of funded charrette pilot projects for communities, to explore how early and meaningful participation can result in a positive approach to growth, development and change

- Strengthen planning policy to require collaborative, charrette-based planning for major developments and in preparing Local Plans

- Adapt planning policy to recognise when charrettes have been undertaken so that future stages in the process fully take account of those community decisions, and provide ongoing support for them

- Promote the use of design codes with community input as part of the planning process to ensure outputs from collaborative planning and placemaking processes are delivered

- Promote open planning negotiations regarding community benefits from developments, so that when charrettes are held a proportion of the community benefit funding is allocated to the community involved, e.g. Community Trusts, subsidised workspaces, movement and transport infrastructure

- Make improving the quality of the public realm in cities, towns and villages a priority, and require every local authority to produce a Place Improvement Strategy and Place Charter

- Promote and fund Town Teams with administrative support to involve businesses, creative economy and community groups to review visions and management strategies, and sign off placemaking funding for projects

- Train built environment students in collaborative working methods including charrette systems

- Promote and encourage awareness of design and urbanism among all school-age students, and enable their participation in charrettes

- Set up civic design centres or ‘urban rooms’, where communities can go to understand and debate the past, present and future of their place with a physical or virtual model

A combination of these initiatives will help to bring collaborative processes into mainstream planning and placemaking. Through shared working from an early stage, communities and businesses can help shape and support development that is right for their specific place, and will enable it to grow and thrive.