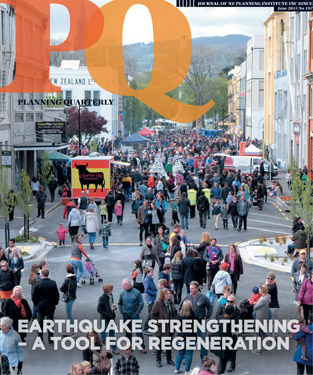

Introduction

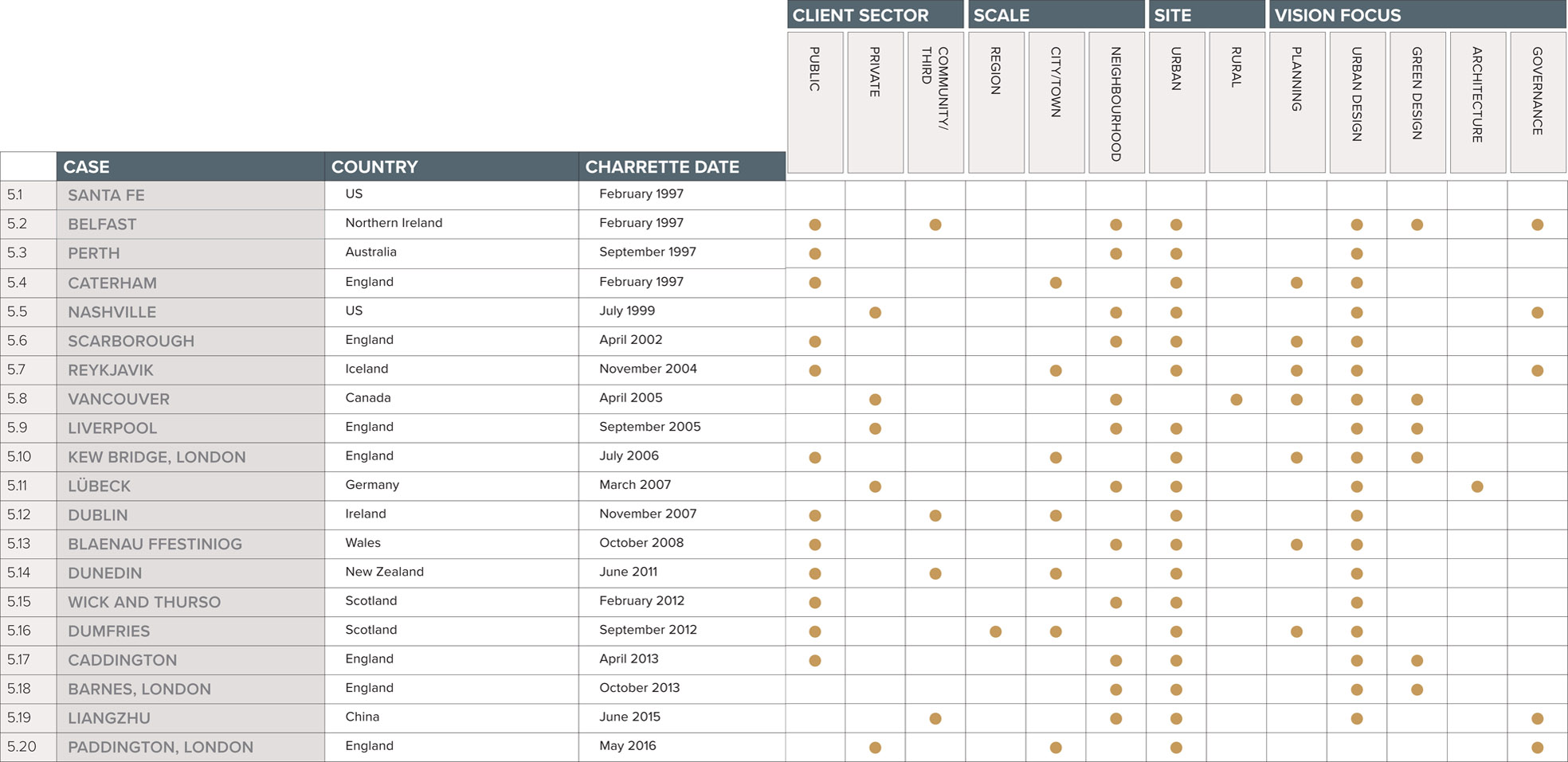

This chapter focuses on twenty international case studies chosen to illustrate a broad spectrum of places and communities around the world where a charrette process has been used.

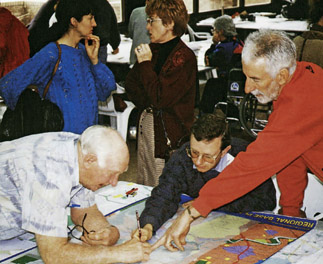

All the processes are related to change. They offer communities a way to express concerns and ideas, which are then considered by the charrette team and reinterpreted as valued and effective inputs: people’s views are heard and honoured.

The case studies demonstrate that charrettes can give people more control over changes to their community and environment. Feelings can often change too – from negative and passive to positive and proactive.

In many instances, the processes have resulted in huge learning curves for the professionals and politicians involved, and in some cases they have changed lives and careers. There are examples of communities getting involved in the pre-charrette organisational phase and the post-charrette delivery phase, whose members then go on to manage and deliver buildings and services. This is in addition to involvement in the charrette itself.

I have worked on many of the charrettes featured in the case studies, collaborating with colleagues from JTP and other practices. For case studies I have not been involved in personally, I am indebted to colleagues for directing me towards selected processes in their parts of the world, and for providing images and text.

While writing this book, I have returned to some places, and visited others for the first time, to assess outcomes from the charrettes and talk to participants. Most quotations come from personal conversations or from telephone conversations with people who participated in the original events.

What has become evident is the clarity of thinking and purpose that was developed through the charrette processes. This was affirmed by the communities and professionals involved. Apart from the tangible delivery of some truly inspiring projects, perhaps the most valuable result has been the relationships that developed within the communities themselves, which has led to further successes that would never otherwise have happened.

The case studies show that communities should not be feared, but welcomed as key participants in planning at any scale, as their input will help deliver what is right and best for the community concerned.

The case studies are presented in three sections: Foresight, Vision and Hindsight. Foresight explains the background to the place and why a charrette was decided on. Vision explains the process and the resulting vision, or masterplan. Hindsight looks back at the charrette from today’s perspective and assesses what has happened since. The final chapter of the book considers the case studies together and draws out the lessons learned.

To give an overview of the case studies and to enable the reader to select charrettes that are of most interest to them, a matrix is included. The charrettes are categorised by location and date, with category headings as follows.

Client Sector

Depending on the body that initiated the charrette process, they are differentiated as ‘Public’, ‘Private’ or ‘Community’/Third. Public sector includes local authorities, non-governmental agencies and national governments. Private includes private landowners, land promoters or masterplan developers, or developers who will go on to build out the resulting scheme. Community/Third includes civic or charitable bodies or community groups. In the latter case, raising funds to involve professional facilitators can be a key challenge.

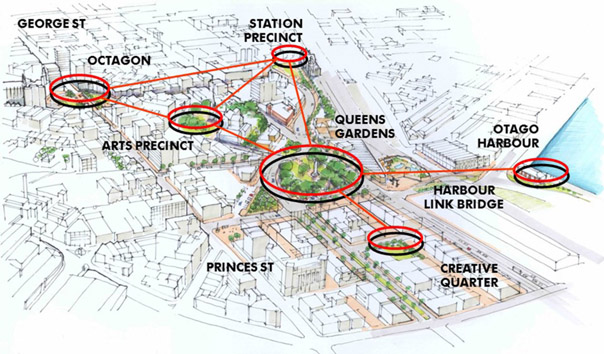

Scale

The ‘Regional’ category includes charrettes that cover more than one distinct settlement and deal with connections and infrastructure. ‘City/Town’ charrettes may involve a whole settlement, or part of a settlement such as a town centre that is significant enough to warrant engaging the whole settlement community. ‘Neighbourhood’ is more localised and typically covers a site or area that can be treated as a distinct development or regeneration opportunity, and which impacts on people within walking distance from the site.

Site

Most of the charrettes are held in the context of an existing Urban, settlement, be it a city, town or village. The ‘Rural’ category describes a site set in the countryside or bush, distinct from the nearest settlement.

Vision Focus

This category describes the primary professional or subject discipline that is the focus of the charrette – some charrettes fall into more than one category.

The ‘Planning’ category has a strategic focus, which will impact on future planning policy of the particular local community or local government.

‘Urban design’ involves a finer-grained focus that considers land use, layout and the relationship between streets and spaces. ‘Green design’ includes charrettes that have a landscape and/or environmental focus.

The ‘Architecture’ category includes the design of buildings and their relationships with place. And finally, ‘Governance’ refers to community involvement being designed in to decision making in relation to delivery and future management of the place.

Case Studies

5.1 Santa Fe Railyard Regeneration

SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, US

DATE FEBRUARY 1997 CLIENT SECTOR PUBLIC/THIRD SITE URBAN SCALE NEIGHBOURHOOD VISION URBAN DESIGN GREEN DESIGN GOVERNANCE

What to do with a large, valuable railyard that becomes available in the heart of the historic, thriving state capital of New Mexico – who decides?

Figure 5.1.1:

Santa Fe Railyard in 1913

Santa Fe, founded by the colonial Spanish in 1610, is the oldest state capital in the US. The indigenous Pueblo people had previously inhabited the land, living in small village settlements over thousands of years. The ‘modern’ city, set at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the edge of the Rockies, has an altitude of more than 2,100 m (7,000 ft) and a cooler climate than the surrounding lower-lying desert. It is a fashionable and highly liveable city,

characterised by attractive adobe buildings in the historic downtown. It has a burgeoning arts and culture scene, which makes it a popular place for both visitors and residents. In the late nineteenth century, the Santa Fe Railyard was built on agricultural land irrigated by the Acequia Madre (‘mother ditch’). In 1880 the first train arrived at Santa Fe station, and for over 100 years the yard was a vibrant commercial and tourist hub, a focal point for the town. Almost overnight, however, the opening of the interstate highway made the railyard practically obsolete. Depending on the time of year it was either a mud pit or a dustbowl. The 1980s was a time of significant growth for Santa Fe, and the railway land, being close to the city centre, became very valuable. Inevitably the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Rail Company decided to develop the site. Discussions between the city government and the rail company led to the creation of a masterplan, drawn up in Boston, which proposed tearing up the rail tracks, demolishing the buildings and constructing one and a half million square feet of real estate. Local architect Suby Bowden recalls that the plan was first seen at a council design review. The railway put up a for sale sign, and there was ‘uproar in the community, who saw it as their land’. Steve Robinson, President of the Santa Fe Railyard Community Corporation, agrees: ‘There was a strong sense of sadness – is this is what our heritage has come to – another faux-adobe shopping mall and a hotel?’ Eventually there was so much opposition that the masterplan was abandoned. This gave Suby the opportunity to go to the city council and suggest an alternative, more culturally sensitive approach. At that time the town plaza was being taken over by tourists, and the community needed their own space. A concept emerged in which the plaza would be the ‘living room’ for guests, and the railyard would become a focus for families and local people, with a park and weekly community activities. The next bold step was for the Trust for Public Land to acquire the land and hold on to it until they were sure that a park could actually be built. The city eventually bought the property from the Trust in 1995 and then began the process of its conversion into a public, mixed-use development. Having discarded the masterplan proposal, discussions took place locally about how to set up a community-based planning process, and Gayla Bechtol, from the local AIA chapter, suggested an R/UDAT. The concept that citizens would be consulted was unprecedented in Santa Fe, which had a ‘patron’ system going back 400 years. Expertise and free advice is a positive element of R/UDATs, but some local people were concerned that if experts came in to design the railyard, it would discourage participation by the community. It was therefore decided to run ten or twelve months of community-based planning, followed by the R/UDAT. Weekly public meetings took place over six months in 1996, to which anyone could bring their ideas. It was a process of simply listening to the community and discussing what land uses people wanted in the railyard, and what the priorities were. During this time, an R/UDAT steering group was set up to organise the charrette, with a wide range of members including the local AIA chapter, the City Planning Department, the Santa Fe Land Use Resource Center, the Trust for Public Land and the Metropolitan Redevelopment Commission. Suby recollects that ‘there were lots of women in top positions – it was a female-led process which believed you could collaborate’. The charrette was held over three weekends in February 1997. The first weekend focused on a design workshop facilitated by local

designers. One hundred and twenty citizens signed up for the whole weekend. This was followed by a citizen vote to determine land uses, which fed into the R/UDAT on the second weekend.

Figure 5.1.2:

R/UDAT Community Report

The R/UDAT was an intense and creative ‘window’ within a long, drawn-out planning process. The team, led by Charles M Davis, FAIA, included ten volunteer advisors from outside Santa Fe. Members of the team went on town and site tours and did many interviews. They then focused on creating a community plan, which had sections on governance, implementation, planning and transportation, as well as finance. The plan enabled people to visualise what the area might be like in the future, and it also gave the city council information about financial commitments. On the fourth night of the R/UDAT the local newspaper published the results in a special edition, which was distributed to the whole town. During the third weekend, the town’s citizens came together to discuss principles from the R/UDAT proposals and to ratify the plan. By that time many of the same people were attending all the meetings – so, with the benefit of the widespread distribution of the newspaper, a telephone survey was conducted. This revealed 75 per cent support for the proposals among the wider community. Subsequently, the councillors unanimously adopted the plan. Seven thousand people (over 10 per cent of the population) actively participated in a year of public participation through surveys, questionnaires and meetings.

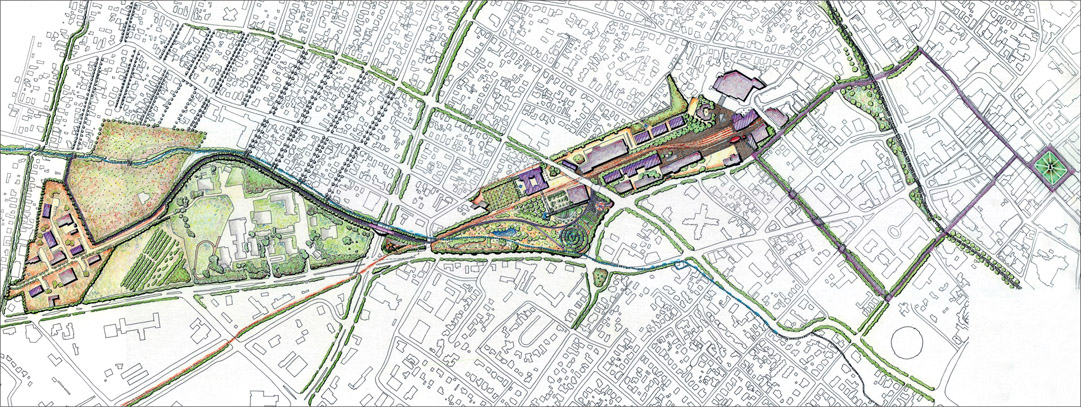

Figure 5.1.3:

Charrette masterplan

The masterplan and design code for the railyard were completed in 2001. ‘Meanwhile uses’ included outdoor activities, such as movies in the park and a farmers’ market. The city council originally offered to manage the park, but the community eventually took it over on a ninety-year lease. An international competition was held for the park and piazza, which was won by a landscape and urban design team headed by Ken Smith, Frederic Schwartz and Mary Miss. The design concepts focused on the

railway aesthetic, indigenous planting and respect for the Acequia Madre, which runs through the site.

Figure 5.1.4:

Santa Fe Railyard Park

The pace of building and refurbishment was slow, but finally in 2008 came the grand opening of the 4-hectare (10-acre) park and piazza. Industrial buildings had been restored for local business use, and new buildings were in operation. A commuter train service was established, and 10,000 people turned out to celebrate the arrival of the first train from Albuquerque. The public involvement process still continues through the management of the award-winning park, which is run according to four values: time, culture, land and oral history. In 2017 an impressive ninety-six public events were held in the park. The Santa Fe Railyard Community Corporation, created out of the R/UDAT process, now offers low rates and rents for businesses, and is developing low-cost housing to the west end of the site.

Figure 5.1.5:

Santa Fe farmers’ market

The regular Saturday farmers’ market is thronged with locals and visitors, and traders are delighted with the facilities laid on for them. For one shopper, the Santa Fe Railyard is now ‘the new downtown – it’s where you come to socialise … you can purchase something from a vendor … next thing you know you’ve been talking for twenty minutes’. Those fighting for their land came from a largely Hispanic background. The farmers were the connection between the land and its agricultural past, and the city’s roots lie in an oral rather than a written tradition. As Suby Bowden says, ‘Santa Fe has a long memory. Perhaps, as a consequence, it moves slowly and is OK with that’. Gayla Bechtol concludes: ‘I am most proud of the democracy that happened – helping people have a voice that otherwise wouldn’t have a voice in the process; that was for me the most gratifying – it was just cool.’Foresight

Vision

Hindsight

5.2 A First Step for the Crumlin Road

BELFAST, NORTHERN IRELAND

DATE FEBRUARY 1997 CLIENT SECTOR PUBLIC SITE URBAN SCALE NEIGHBOURHOOD VISION FOCUS URBAN DESIGN

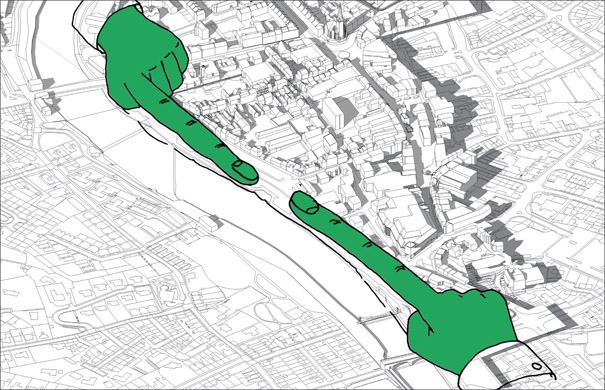

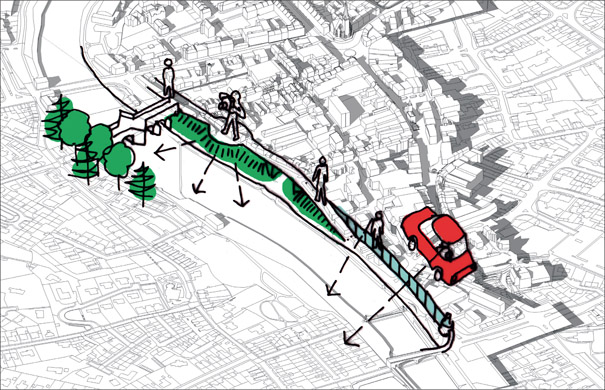

A community planning process was used to take a tentative first step to create common ground between two communities in conflict, by agreeing acceptable uses along the high road they share.

Figure 5.2.1:

British Army mobile patrol along the Crumlin Road during the Troubles, 1971

Crumlin Road is an interface between the Protestant and Catholic communities of North Belfast. For thirty years it was synonymous with the Troubles, featuring regularly on news bulletins around the world reporting a seemingly endless series of attacks and murders. Even after the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, the Crumlin Road was in the headlines again in August 2000 when two loyalists associated with Ulster Defence Association brigadier Johnny Adair were shot and killed while sitting in their jeep. Crumlin Road is one of Belfast’s key arterial routes, linking the city to the Antrim Hills and beyond. Historically, the route connected some of the city’s principal linen mills to the city centre and the docks, and thousands of jobs in manufacturing and shipbuilding sustained the area’s economy. The road is also known for being the location of many significant buildings, such as the Mater Hospital, Crumlin Road Gaol and Crumlin Road Courthouse. As well as churches and community buildings, there are mills, shops and homes along the road. By 1996 the Crumlin Road had seen thirty years of decline and neglect due to the Troubles, the waning of Belfast’s economy, especially in shipbuilding, and the blight of a planned but unrealised road widening scheme. As well as being the site of some of the city’s worst dereliction, the Crumlin Road area was also one of the most deprived in the city. Housing and territory have long been key issues in North Belfast. The Protestant areas have been depopulating while the Catholic

population is growing and requires more space for housing, but the former community would not concede to the latter.

Figure 5.2.2:

Aerial photo along the Crumlin Road looking west to the Antrim Hills

Making Belfast Work (MBW) was launched in 1988 by the Northern Ireland Department of the Environment, to strengthen and target more effectively the efforts being made by the community, the private sector and the government to address the economic, educational, social, health and environmental problems facing local people. In the mid-1990s MBW decided to focus on the regeneration of Belfast’s arterial routes. The intention was to bring marginalised communities into engagement with public authorities by building on a sense of optimism, encouraged by a new era of ceasefire. In September 1996 John Thompson & Partners (JTP) was appointed to undertake a community planning process to develop a consensus vision for the future of the Crumlin Road. At the time it was seen as a dangerous road, with highly demarcated territory and with no sense of free movement. By bringing the two communities together and focusing on a road they both used, MBW hoped that some compromise and agreement might emerge. A key objective was to find future uses for the gaol and courthouse, both designed by architect Sir Charles Lanyon, and built in the mid-nineteenth century. Since the declaration of a ceasefire in 1995, these listed buildings stood vandalised and unused, facing each other across the Crumlin Road. MBW was seeking new uses for them both but needed the permission of the community. The initial aim was to hold a publicly advertised ‘community conference’, with the potential to produce a ‘community plan’. However, following preparatory work in Stage One, community leaders believed this proposal to be too prescriptive and potentially divisive.

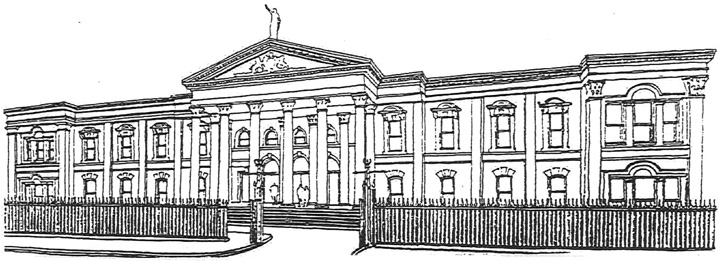

Figure 5.2.3:

Crumlin Road Courthouse

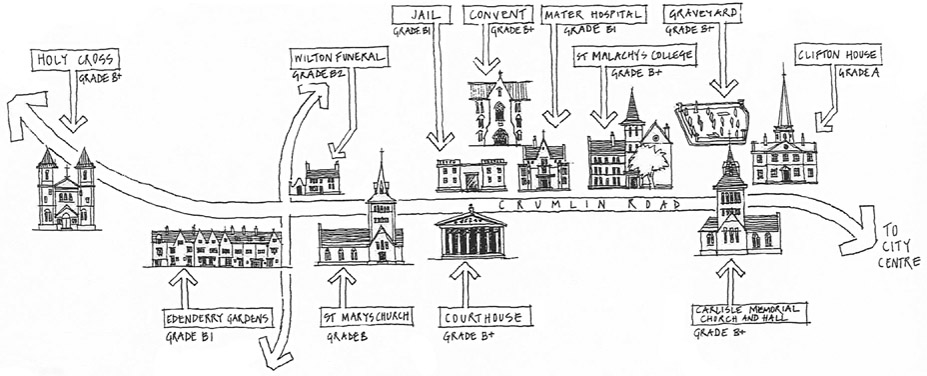

Figure 5.2.3A:

Listed buildings along the Crumlin Road

A steering committee was formed to oversee the preparation of the event, under the chairmanship of Jonathan Davis, then a director at JTP. The practice was viewed as a trusted and neutral party, and it was important not to force the timetable. A critical role of the steering committee was for the representatives of both the nationalist and loyalist communities to meet and broker a mutually acceptable venue, agenda and format for the event. Intense discussions ensued during which the process was debated and sometimes put in doubt. An agreed position was eventually worked out, which provided clear definitions of what the process sought to achieve, and what it did not. To do so, two lists were created as follows. What the process IS:

What the process ISN’T:

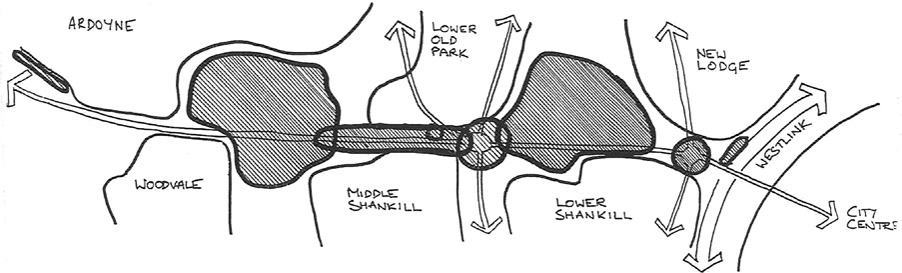

The event was redefined as an invitation-only ‘Ideas Weekend’ with the output to be a ‘flexible framework’ rather than a masterplan, which would form the basis for further discussions. As the agreed title of JTP’s subsequent report stated, this was to be ‘A First Step for the Crumlin Road’. The Ideas Weekend took place over five days between 20 and 24 February 1997 at the Spires Conference Centre in central Belfast. On Day one, following a project briefing, the facilitation team walked the full length of the Crumlin Road from west to east – a walkabout that was pre-notified to the communities to ensure safe passage. Over 100 people attended the event, and participants took part in ‘future workshops’, which discussed the multifaceted problems of the Crumlin Road and gave participants the opportunity to consider ideas for the area, how change might be brought about, and by whom. During design table sessions the future of the Crumlin Road’s public buildings, the relationship between the various residential communities and improvements for the overall quality of the environment were explored. A ‘way forward’ workshop focused attention on viable next steps. Following the two public days, the JTP team drew together conclusions and recommendations to provide a flexible framework for a possible way forward. The results were presented back to the weekend participants in a slideshow. Four potential project clusters were identified, which separately or together could have the potential to contribute to the regeneration of the area. In line with the steering committee’s objectives, it was stressed that these were examples of how regeneration might be achieved, and were a first step, not a final outcome. Considering the Ideas Weekend process took place over a year before the Good Friday Agreement of 10 April 1998, it was a significant achievement that the event took place at all. It reflected the efforts being made by many local people as part of the peace process of the mid-1990s. The event seemed to create a shift of imagination among participants, enabling a fragmented and depressing landscape to be seen as a cluster of opportunities that had the potential to be exploited for the benefit of all.

Figure 5.2.4:

Team walkabout on day one of the ideas weekend

Looking back at the process, Roisin McDonough, formerly of MBW, recalls: ‘I was very enthused about the process; it gave people a very keen sense of what things could look and feel like. Building relationships was a good thing, and the process encouraged a participative and deliberative form of democracy – it was intelligent.’ The use of co-design sketching techniques gave visual expression to participants’ ideas, and illustrated practical means by which these could be achieved. What the actual event did not do, as some had feared it might, was to derail the hard work and carefully developed relationships that had been established over the preceding months by the steering committee. During the twenty years since the event, resources have been directed into the area, which has resulted in new development and regeneration, better environment management and a brighter feel. But Crumlin Road still suffers from underinvestment, and the core issues have not gone away: there are very high levels of deprivation, and housing is still off the agenda. The 1997 collaborative event, with its strict ground rules, supported a growing awareness that interfaces could be created; an acceptance of the permanent physical divide between two communities. Communities would be separated in a way that would maintain the peace, as long as the interfaces were based on common interest and also respected the symbols and expression of community traditions. For example, both communities agreed that retail and community uses were acceptable for interface land, but not housing, as this would be construed as a territorial move. Consequently, in January 2016, after a decade of controversy about what should be done with the former Girdwood Barracks in North Belfast, a £11.7m community and leisure hub has opened, offering first-class leisure, community and education facilities. The Ideas Weekend also identified the potential for investment in the Crumlin Road Gaol as a way to develop leisure, cultural and heritage opportunities, which could have significant tourist appeal. In May 2002, the report of the North Belfast Community Action Project team discussed the need for a large-scale physical regeneration project in North Belfast, and highlighted the potential of the former Crumlin Road Gaol. By the end of 2012 the prison had reopened its doors as a tourist attraction, business space and conference centre. While much of the building is still to be fully let to businesses, the museum has been successful in attracting visitors, among them many former inmates from both sides of the political divide.

Figure 5.2.5:

Crumlin Road project clusters

Figure 5.2.6:

Crumlin Road Gaol today

Opposite the gaol, the courthouse, having suffered a number of fires in recent years and having failed to attract investment for adaptation and reuse has lain in a terrible state, a shadow of its former magnificence. But in March 2017 a Liverpool-based developer, Signature Living, bought the building with the intention of spending £25m to convert it into a 160-bedroom hotel, an initiative that has been supported by both sides of the community divide. The Ideas Weekend was held at a critical time in Belfast’s history, and it succeeded in bringing people together, building relationships and establishing agreed positions on many issues. A number of the identified physical projects have subsequently been delivered in a way that was jointly envisaged and agreed at the 1997 collaborative event. Memories are still raw for many who live in this divided community, but the potential exists for further development that builds on the growing success of Northern Ireland’s capital city. It is to be hoped that in the nottoo-distant future political progress in Belfast will enable a new round of investment to be directed to key opportunity sites along the Crumlin Road, to everyone’s benefit.

Foresight

Vision

Hindsight

5.3 Revitalising Midland – A Railway Town

PERTH, AUSTRALIA

DATE SEPTEMBER 1997 CLIENT SECTOR PUBLIC SITE URBAN SCALE TOWN VISION PLANNING URBAN DESIGN

Revisioning a former railway town has revived the spirit of the community, formed a new creative economic base and attracted investment to revitalise neighbourhoods and landscapes.

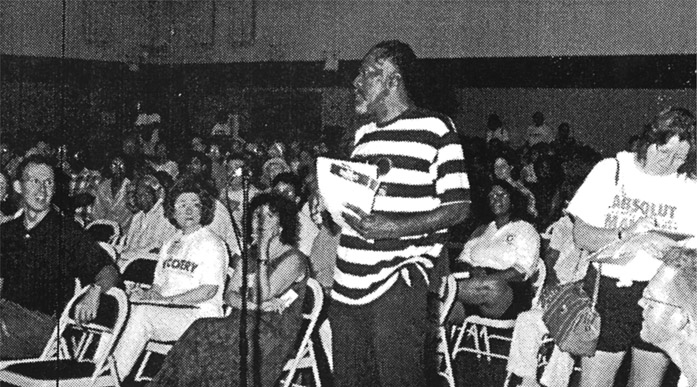

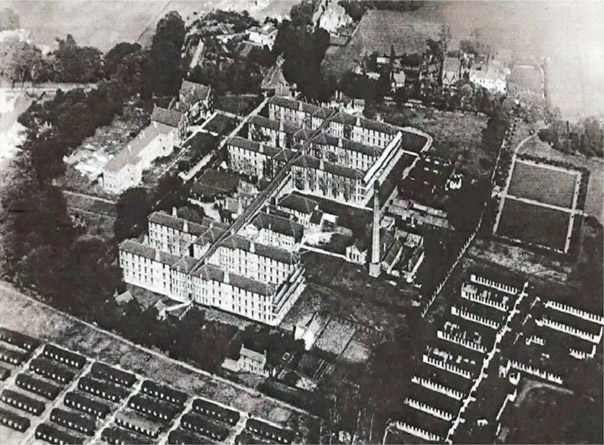

Figure 5.3.1:

Heritage image of Midland Railway Workshops

The township of Midland was established in 1891 at the junction of two main highways on the eastern fringes of Perth. Settlers had occupied the privately owned land since the 1830s, but the arrival of the Midland Railway Company in 1886 prompted its subdivision and sale. In 1902 the Western Australian Government Railway Workshops were relocated from Fremantle to Midland, and the rapidly expanding town was built on a history of heavy engineering, with a fine tradition of craftsmanship and innovation – skills that were passed from generation to generation. The Railway Workshops were vital to the development and maintenance of the Western Australian rail system, and a crucial training ground for the skilled workforce of some 4,000 people. A new rail station and shopping centre were built in the early 1970s, and the town’s fortunes looked assured. However, the closure of the Railway Workshops in 1994 had an immediate and devastating impact on Midland’s local economy and its multicultural community, including European migrant workers. It was not just the loss of their livelihoods, but also their traditions, camaraderie and pride in their work. Despite the best efforts of the authorities, including locating government and shire offices in the town centre, Midland fell into sharp decline and the community’s morale suffered. It was agreed by the City of Swan and the Western Australia Ministry of Planning that a community plan was needed to address the complex and interrelated challenges and opportunities. Ecologically Sustainable

Design (ESD), led by Chip Kaufman and Wendy Morris, was appointed to run a charrette process and develop integrated proposals, which could be implemented with the backing and involvement of the community.

Figure 5.3.2:

Midland Revitalisation Charrette

The ‘Midland Revitalisation Charrette’ was held in 1997 with the support of a wide range of local bodies, to develop a strategy for this declining sub-regional centre and bring together a diverse group of stakeholders to craft a shared vision for the future of the town. The charrette process ran for five days between 11 and 15 September 1997 at three locations in Midland. At each venue hundreds of local residents worked with the ESD team to consider the range of issues ‘all at once’. During the first evening meeting, the mechanics of the charrette process were outlined and the local community had an opportunity to voice their concerns. Over the next days the multidisciplinary team collaborated intensively with local residents, including young people, businesses, landowners and government agencies, to explore and indicatively design opportunities and solutions.

Figure 5.3.3:

Plan of Railway Workshops redevelopment area

On the concluding evening Chip Kaufman presented the illustrated vision for Midland’s revitalisation. Design ideas and an economic strategy were presented for the whole of Midland, with the key focus on the heart of the town. In addition, a range of proposals were presented for transport improvements in and around the town and the rehabilitation of the Helena River and Blackadder Creek. A key theme running through the presentation was an appreciation of the many assets of the town, and how they could be brought to the fore using the concept of ‘unleashing the giant’. From those few concentrated days of workshops and brainstorming emerged what became the blueprint for the transformation that followed. The charrette identified the growth areas of Swan View, West Stratton, Swan Park and Midland TAFE (Technical and Further Education) as places that had the potential to be strengthened with infill development, improved local centres, better linkages, and safer, more attractive streets, parks and environmental areas. Key proposals for the heart of the redevelopment area included a 1-hectare (2.5-acre) oval of parkland, to be surrounded by 130 two-storey terraced houses, each with its own private front and rear gardens, and within easy walking distance of the town centre.

Figure 5.3.4:

‘Unleashing the giant’ cartoon

Figure 5.3.5:

Sketch of ferry landing and marina at Woodbridge Landing

The charrette process enabled positive engagement with Aboriginal people who used to gather in a green space called Tuohy Gardens. This triangular street block with its confusing, uninviting pedestrian routes and hidden corners had become an ongoing problem area attracting antisocial behaviour. The charrette worked directly with the local Aboriginal community and proposed to solve all these problems by creating two new streets, redeveloping Tuohy Gardens as two-storey terraced housing, and by identifying a more suitable location nearby for Aboriginal gatherings and a cultural centre. Following the charrette, the Shire President Councillor Charlie Gregorini was delighted that so many people embraced the potential for growth and development. He acknowledged that the City of Swan had set a new standard for how local government could work with its community in planning future growth in a sustainable manner. Local resident Brian Hunt recalls: ‘Midland had been languishing for some time, and people had come together at various times before to try to decide what to do and they produced nothing. The charrette was really helpful in stimulating a positive attitude in the community – they had skilled people that could sketch, draw and analyse but didn’t preach.’ Virtually all community groups supported the proposed charrette outcomes, including, most importantly, the Midland District’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry. A steering committee was formed, with representation from the community and business groups and the council, which led to the state government establishing the Midland Redevelopment Authority (MRA) in 2000. This new agency was allocated land in the town centre, and the nearby 70-hectare (173-acre) Railway Workshops site, as the first stage of the redevelopment area. Building on community ownership of the vision, the MRA has demonstrated an unwavering commitment to ensuring that the community continues to share and shape the charrette’s dream and passion. Local communities and interest groups have been actively engaged in the project through further visioning exercises, forums, face-to-face liaison, local media, newsletters and reference groups. In particular, ESD were appointed to undertake another charrette in 2007 to review the process and outcomes and refresh the vision. Kieran Kinsella, CEO of the MRA, explains: ‘I came to deliver the charrette outcomes, which had really strong community support. We need to keep true to the issues that came out and we keep refreshing our masterplan every four to five years – the people of the town continue to advocate for the things still to be done.’ New life has been breathed into cultural landmarks, such as the site of the Midland Railway Workshops, which is central to the area’s sense of place. A new urban village has been created in the workshops precinct, with the retention and reuse of some of the original workshop buildings, and a mix of new residential, commercial, health, education and creative industry uses. Located west of the site, Woodbridge Lakes has been developed as a new environmentally friendly, medium-density neighbourhood with attractive public spaces and parklands. There are

committed affordable housing options to support a diverse population. Apartments and other higher-density dwellings are interspersed among parks, shops, cafes and transportation to provide an inner-city lifestyle. More than 150,000 square metres of new commercial and retail floor space has been created in the Clayton Street shopping hub, Midland Central.

Figure 5.3.6:

Midland Workshops Heritage Open Day

The Midland Workshops Heritage Open Day, hosted by the Metropolitan Redevelopment Authority, was held on Sunday 8 September 2014 and gave local residents, former workers and the wider Perth community an opportunity to look inside the iconic buildings and celebrate this important heritage precinct. Perhaps the greatest achievement of the MRA, and the principal reason for its success, has been the continuation of partnerships established at the time of the first charrette, which have been nurtured and maintained since by the various stakeholder groups. The organisations that helped formulate the concept plan for a revitalised Midland have remained active and enthusiastic participants in the process – not always in total agreement, but committed to realising a joint vision of a vibrant and exciting town. Midland is now brimming with confidence as local investors, developers, businesses and residents commit to the continuing journey ahead, and have become a formidable army of ambassadors for the town.

Foresight

Vision

Hindsight

5.4 Regeneration of a Historic Military Barracks

CATERHAM, SURREY, ENGLAND

DATE FEBRUARY 1997 CLIENT SECTOR PRIVATE SITE URBAN SCALE NEIGHBOURHOOD VISION URBAN DESIGN GOVERNANCE

Collaborative masterplanning transformed a former army barracks into a popular and award-winning mixed-use village community.

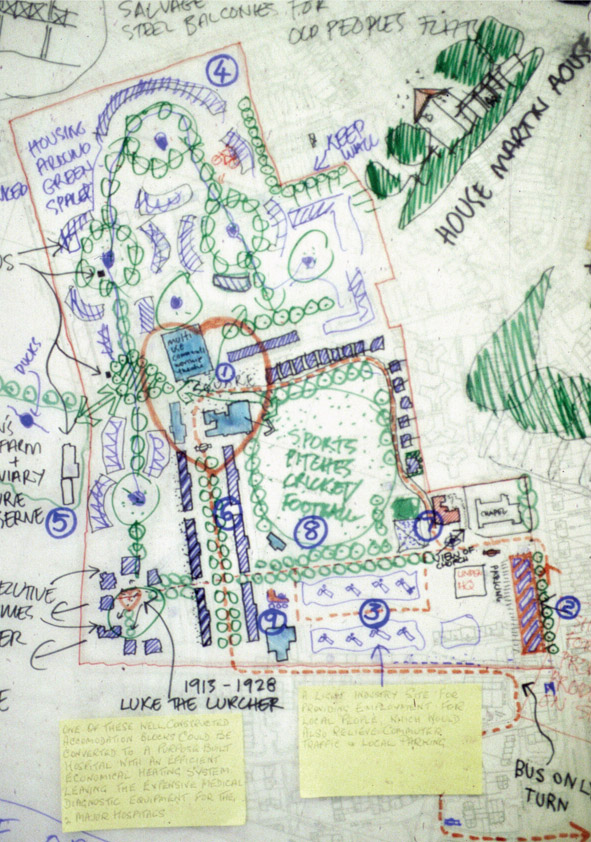

Figure 5.4.1:

Guards at Caterham

The Guards’ Depot in Caterham, known as Caterham Barracks, was established in 1877 as the basic training establishment for the five regiments of Foot Guards, part of an elite personal bodyguard to the reigning monarch. Enclosed by a perimeter wall, the barracks included a Grade II listed chapel, designed by William Butterfield in 1885. In 1960 the Guards’ Depot transferred to Pirbright, and the barracks were used to accommodate various regiments. Many Guardsmen who had trained at the depot settled in Caterham after completing their service, and the local community was able to use the barracks facilities for sporting events, including boxing tournaments, and cricket and football matches. Sadly, this changed when security was tightened in August 1975, after an IRA bomb targeting soldiers exploded in a local pub. The barracks’ closure in 1995 left a void in the community, and had a significant impact on the social and economic life of the town. A local authority community consultation process in 1997 resulted in a planning brief with minimal built development (sixteen new houses plus the barrack blocks converted to residential) and unrealistic expectations regarding community amenities. Although the brief was considered unviable by many developers, the site was bought by locally based Linden Homes. Linden recognised the local and historic importance of the barracks, and they were committed to delivering a high-quality neighbourhood. They also felt it was important to enable local residents and others to have a real input into the evolution of proposals, and that additional development would be acceptable if significant community benefits were delivered, thereby creating a more dynamic and sustainable community. Linden Homes appointed John Thompson & Partners (JTP) to create a masterplan for the site using a participatory process, including a

‘Community Planning Weekend’. This marked the first time that a large-scale collaborative planning process had been promoted in the UK by a private developer.

Figure 5.4.2:

Drawing from one of the hands-on planning groups

The Caterham Barracks Community Planning Weekend took place in the NAAFI building between 27 February and 3 March 1998, and was attended by more than 1,000 people. The event was structured around a combination of topic-based workshops, together with a large number of hands-on planning sessions, through which participants could discuss and actively contribute their design ideas. Teenagers from several local schools were involved, and local people could tour the barracks in a bus. Over the course of the weekend a consensus emerged in favour of creating a balanced village community, including more than 360 homes (around 300 new-build) and a mix of uses set in a high-quality environment that respected the history of the site. New homes were laid out around the cricket green and on traditional street patterns. There were community facilities of a high standard, and green spaces managed by a new Community Trust. Participants identified a number of possible community uses for existing buildings retained as part of the new neighbourhood, to be paid for by the increase in the number of homes provided on site. Uses for the buildings have, by and large, stood the test of time. Local resident Marilyn Payne led the call for more facilities for young people, and within a few months ‘Skaterham’, a youth project providing skateboard, inline and BMX facilities, was set up in the former gymnasium. In March 2002 it transferred from the gymnasium to the listed chapel, and now has thousands of members.

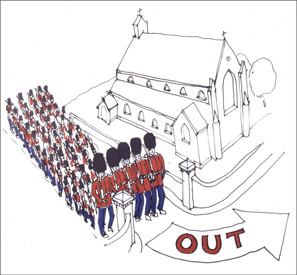

Figures 5.4.3 & 5.4.3A:

Guards marching out – community ‘guardians’ marching in cartoon

Figure 5.4.4:

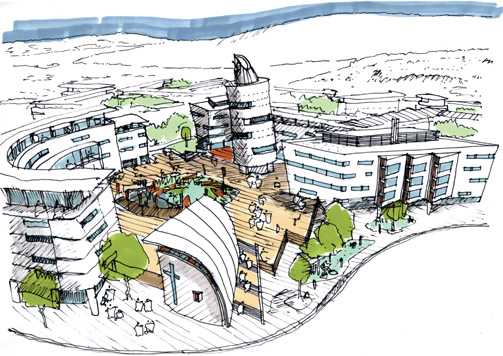

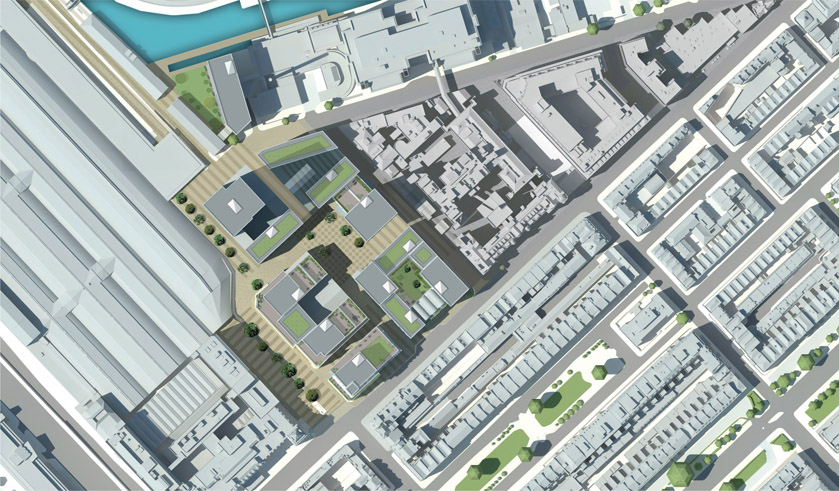

Vision for Caterham Barracks – aerial drawing

The Community Planning Weekend marked the beginning of an ongoing process of collaboration between the community, the developers and the local authority, with the aim of creating a responsive new neighbourhood with a strong sense of place. A steering group was established to provide a forum for local residents, councillors and special interest groups. A number of specialist sub-groups met on over fifty occasions, involving over 100 local people. Ivan Ball, Linden’s Project Director for redevelopment of Caterham Barracks, found himself spending more and more time working with the community. He subsequently moved into the village and became known as ‘Mr Caterham’. In due course, a series of recommendations were presented to Tandridge District Council with full community backing. The council changed its policy for the site and granted outline planning approval in June 1999, with the proposals delivered through a six-phase programme that was completed in 2008. Governance of the new village at Caterham came about through the foundation of a Community Development Trust. This was the direct result of the Community Planning Weekend, during which local people expressed a desire for ongoing involvement in the creation and running of their community. The village at Caterham was one of the first places to integrate private and affordable housing. The design of the affordable housing was indistinguishable from the private accommodation for sale, thereby achieving a genuine integration of tenure. The Village has become known as a very healthy place to live, due to the provision of walking and cycle routes, and the access to open space. The ‘Village Flyer’ bus service began in September 2000, when the first residents moved in, to provide a transport link from the Village to Caterham railway station. Initially subsidised by Linden Homes, it is now funded through the residents’ service charge.

Figure 5.4.5:

The Arc, Caterham

Figure 5.4.6:

The Village at Caterham – village green

The community planning process resulted in a highly viable development: over 360 new homes and millions of pounds’ worth of community projects, including a nursery, a health and fitness centre, a swimming pool, a cricket pavilion, sports pitches, exhibition and rehearsal space, and an indoor skate park. The collaborative process and the resultant mixed-use development and community outcomes were researched and described in the publication ‘Social Sustainability’, published by JTP in 2013. The success of the Village at Caterham has been recognised through numerous national and international awards, including the RTPI National Awards for Planning Achievement 2000 ‘Award for Planning for the Whole Community’. More importantly, it is the views of the community that have defined the development. An early resident of the converted barrack blocks emphasises the excitement of community collaboration: ‘When you’re in on the beginning of things – which is what the whole thing here was about – there is that sense of buzz and excitement. What’s it going to turn out like? How much control will you have over it? Can you actually make it how you want it to be?’ And Ivan Ball concludes: ‘It’s just a fantastic scheme – you’ve got nice trees, nice old buildings, and it’s a big enough site that we’ve been able to put in all the new facilities. I know I’m terribly biased, but if you’re looking for a new home, this is as good as it gets.’

Foresight

Vision

Hindsight

5.5 East Nashville Post-Tornado R/UDAT

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE, US

DATE JULY 1999 CLIENT SECTOR PUBLIC SITE URBAN SCALE NEIGHBOURHOOD VISION PLANNING URBAN DESIGN

A consensus vision helped rebuild and revitalise a forgotten suburb, devastated by tornadoes in the 1930s and 1990s.

Figure 5.5.1:

The destructive impact of the tornado in East Nashville

For many years East Nashville was a forgotten part of the city, located on ‘the wrong side of the river’. This residential quarter had grown up in the early part of the twentieth century as a traditional, walkable neighbourhood of homes and community amenities, with local services at key junctions. Although it was separated from downtown Nashville by industrial land and the Cumberland River, the extensive network of trolley lines gave access to employment and services. Then a huge fire in 1916 and a tornado in 1933 damaged the area’s vitality, and the building of the interstate highway encouraged the movement of the middle classes to the outer suburbs. From then on and for decades, East Nashville was largely ignored. On 16 April 1998 another devastating tornado passed through Nashville’s town centre and inner-city neighbourhoods, and East Nashville was worst hit. Local estate agent Cindy Evans describes the impact: ‘The hurricane went downtown, broke office windows and then came across the river, and the restaurant where my friend worked had its roof blown off – she was blown from one room to another. Throughout the neighbourhood fallen trees were everywhere – you couldn’t see the street. It’s like we were hit by a bomb.’ Most tellingly, Cindy concluded: ‘It wasn’t until late at night that the news said East Nashville had been hit – that’s how inconsequential we were.’ The initial response to the tornado was impressive, with the East Nashville community and public sector pulling

together to clear streets, provide emergency help and restore services. Three months later, in July, Mayor Bredesen set up the Tornado Recovery Board, which decided to apply to the AIA to bring in an R/UDAT to create a plan for regeneration, simply because of its emphasis on community participation. It was felt that the tornado could be a catalyst to take a downtrodden neighbourhood in decline and help make it much better than it had been before. Carol Pedigo, one of the key forces behind bringing the R/UDAT to East Nashville, describes charrettes as: ‘The best-kept secret – you’re always better off with more ideas than just your own.’

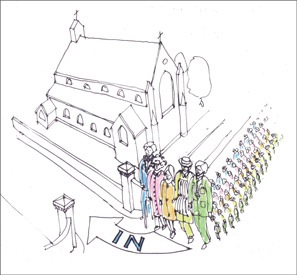

Figure 5.5.2:

Open-mic day at the R/UDAT

In 1998 Hunter Gee was setting out on his career as an architect, and was very keen on community involvement. He was asked to chair the local steering committee, which included representatives of businesses, neighbourhood associations, public sector officials and councillors. The steering group raised the $50,000 to fund the R/UDAT and, as Hunter explains, ‘one of the keys to success was the work we did over months to get the entire community represented – we spent many months building buy-in’. The multidisciplinary R/UDAT team was led by Bill Gilchrist and comprised nationally recognised land-use professionals from across the region, with backgrounds in landscape, housing, transport, venues and stadiums, community networking, urban design and management information systems. The R/UDAT was held over four and a half days in July 1999. It started with a team tour of the area, followed by meetings with politicians and key stakeholders. Day two was an open-mic day at the Martha O’Bryan Center, where the team listened to local people who lined up to explain their likes, dislikes, needs and visions. The location of the meetings was critical, to encourage a wide cross-section of the community to attend, and the open-mic session was programmed ‘from 9am until the last person who has something to contribute’. Around 400 people were involved, and over 100 people spoke into the microphone. Key themes to emerge included the value of having a diverse community and the need to ensure that regeneration did not force people out of the area. As well as the need for reconstruction following the tornado, other concerns raised included social services, greenway development, parks and playgrounds and crime prevention. Participants stressed the need to attract people and better business to East Nashville, and residents said time and time again how they wanted the area to be restored to its original beauty and splendour. Following the open-mic session, the R/UDAT team worked intensively, day and night, right up to the public report back presentation on Monday 19 July. One thousand people turned out to hear the outcomes from the charrette, which were presented using an overhead projector and transparencies.

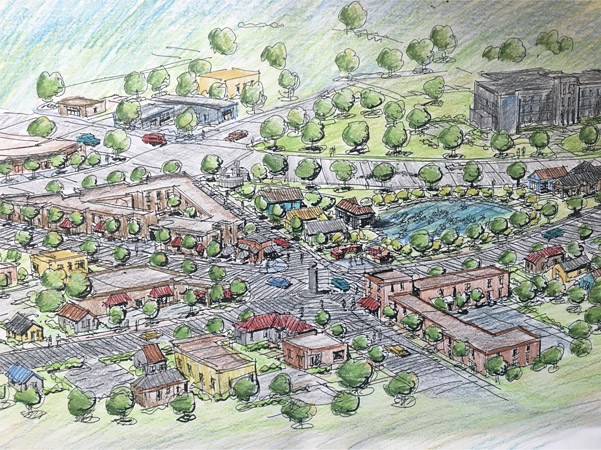

Figure 5.5.3:

Sketch of a revitalised ‘100% corner’ from the East Nashville R/UDAT

Figure 5.5.4:

Aerial sketch of Five Point, East Nashville

Three primary tasks were identified for the East Nashville community to undertake in order to enact the recommended changes. One was the need for community organisation. The second was a focus on developing public spaces and linkages. The third was the adoption of land-use policies that would enhance the unique character of this urban community. The recommendations focused on the two major strengths of East Nashville that should be nurtured and receive investment, namely the diversity of the community which lay at the heart of the area’s identity, and the essential quality and robustness of the urban fabric. The team identified the key importance of the commercial uses at road junctions within the neighbourhoods, and promoted these so-called ‘100% corners’. Hunter Gee recalls that the main recommendation was the creation of a community council to oversee implementation of the R/UDAT’s proposals. There was also a proposal to market the area and recognise that it had huge assets, such as the walkability of the neighbourhood. A logo was created and a body established called ‘Rediscover East’, which still exists today. Rebuilding didn’t happen overnight, of course: for ten years there were blue tarpaulins covering damaged buildings everywhere. One thing Hunter would change about the process, if he could, would be the availability of funding for public infrastructure improvements: ‘We could have found funding if we had staff – you need paid staff.’ A couple of years later, some R/UDAT team members returned to East Nashville and challenged the city to invest in more staff for Rediscover East. Hunter believes that the process of building the buy-in and holding the charrette set in motion a rising market that hasn’t stopped, even to this day. East Nashville is now listed as one of the hippest neighbourhoods, which brings with it its own ‘gentrification’ challenges, such as how to deliver affordable homes. In 2012, building on an idea first discussed and sketched at the R/UDAT in 1999, the Metropolitan Development and Housing Agency announced the redevelopment of Cayce Place for 32 hectares (80 acres) of public housing. This meant tripling the density to enable bringing in mixed uses, including health provision. Smith Gee studio held a charrette attended by over 100 local stakeholders and citizens, and the resulting plan will deliver more than 2,300 new homes, open spaces and 20,000 m2 (215,300 sq ft) of commercial and community uses. Despite the successes and more recent acclaim for East Nashville, it’s important to remember that the emotions and memories associated with the tornado’s devastation have not been entirely forgotten. Cindy recalls: ‘The tornado took down the huge sugar maples – when I drive home through these streets I can still remember how it used to be.’

Figure 5.5.5:

Rediscover East logo

Figure 5.5.6:

Revitalised and vibrant ‘100% corner’ in East Nashville

Foresight

Vision

Hindsight

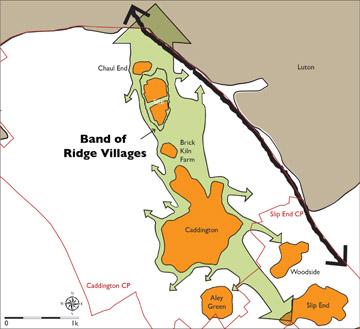

5.6 Town in Decline to most Enterprising Place

SCARBOROUGH, NORTH YORKSHIRE, ENGLAND

DATE APRIL 2002 CLIENT SECTOR PUBLIC SITE URBAN SCALE TOWN VISION PLANNING URBAN DESIGN GOVERNANCE

The community of an iconic but declining seaside resort were empowered to create and proactively deliver a vision for the cultural and economic renaissance of their town.

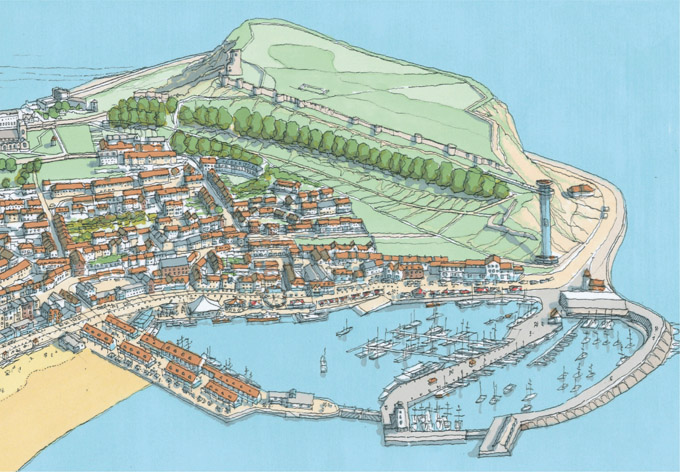

Figure 5.6.1:

View of South Bay, Scarborough, looking towards the castle

At Scarborough, North Yorkshire, springs were discovered in the early seventeenth century, bubbling from the base of South Cliff on to the seashore. This marked the beginning of England’s first seaside resort. Early visitors to the spa town were the aristocracy and landed gentry, who stayed for the summer season with their families and servants. The advent of the railways in the Victorian era led to the arrival of thousands

of day-trippers and holidaymakers, transforming the town’s local economy and leading to the construction of large hotels on the seafront and a wide range of leisure attractions. Scarborough’s expansion continued into the first part of the twentieth century, with municipal initiatives creating 142 hectares (350 acres) of public parkland. New housing estates were built on the outskirts of the town, and light industry arrived in the form of coach-building, printing, food-processing and engineering businesses. However, Scarborough’s fishing industry was in steady decline, and from the 1970s tourism also started to suffer, due to the growing popularity of package holidays to the Mediterranean. By the end of the twentieth century the town seemed unable to halt the decay and dereliction that was steadily eroding the assets of this once-splendid place. Scarborough’s geographical isolation, which had originally been part of its attraction, became a distinct threat. Its relatively poor road and rail links to York, the nearest city, meant that people quipped about it being ‘forty miles from England’. The town fell off the prestigious and lucrative political party conference circuit due to a lack of investment in hotel and conference facilities. By the turn of the millennium Scarborough had become a low-wage economy with a workforce ill-equipped to face the challenges of the twenty-first century. The empty holiday bed-and-breakfast accommodation was attracting hundreds of homeless people, some fresh out of prison, and pockets of poverty appeared, with one council ward being listed in the top 10 per cent most deprived in the country. At that time Scarborough was not looking to change – it was focused on being a seaside town, and nothing more. Business yields were poor in the hospitality sector, and discounting was seen as the only option to maintain a competitive edge. However, work led by Scarborough Council was having some positive effects, which were recognised by the Most Improved Resort Gold Award from Marketing in Tourism. European funding was also secured to help regenerate some of the town’s suburban housing estates. A major impetus came in the autumn of 2001 when Yorkshire Forward, then the Regional Development Agency for Yorkshire and Humberside, launched its Urban Renaissance programme, led by Alan Simpson. The programme, a response to Richard Rogers’s ‘Urban White Paper’ published the previous year, had the ambition of creating a ‘World Class Region’, and viewed environmental quality as a driver for social and economic regeneration. John Thompson & Partners (JTP) and West 8 from the Netherlands were appointed from the Yorkshire Forward consultant panel to create a vision for Scarborough, with an action plan for its delivery. The aim of the vision-building process was to work with the local community to explore every asset of the town and create a consensus as to how Scarborough could throw off its outdated image and move confidently into the future. Following an initial period of research and ‘community animation’, which involved talking to many residents and stakeholders, the process culminated in ‘Scarborough’s Renaissance Community Planning Weekend’. This five-day charrette was held at the Spa Conference Centre in April 2002, with over 1,000 people taking part in two days of topic workshops and hands-on planning sessions. The public event began with a welcome from Eileen Bosomworth, then leader of Scarborough Council, and an address by playwright Sir Alan Ayckbourn, long-term resident and director of the town’s well-known Stephen Joseph Theatre. His motivational speech highlighted the rare combination of assets, both environmental and community, that existed in Scarborough, and on which the renaissance of the

town could be built. Talented members of Rounders, the Stephen Joseph Youth Theatre, dramatised life in the town and the meaning of regeneration in a highly entertaining ten-minute performance.

Figure 5.6.2:

Stephen Joseph Theatre – Rounders’ dramatised interpretation of regeneration

Figure 5.6.3:

Participants at the Community Planning Weekend

Teenagers, youth workers and students from several schools participated in the charrette, an open and informal event that gave people the opportunity to take part in workshops on topics such as Arts, Culture and Entertainment, Housing and Young People. The final session on the Friday focused on hands-on planning, where ideas from the workshops were discussed in more

detail, around plans of the town, plotting opportunities and starting to produce ideas for positive change. One participant said that it was a liberating process compared with typical town meetings, as the event encouraged a much more pleasant and productive dialogue. The workshops continued on the Saturday morning, and in the afternoon participants divided into eight groups and went out into the streets to study particular parts of the town. Returning to the spa, the groups recorded their ideas on plans and presented them back to the whole assembly in a plenary session.

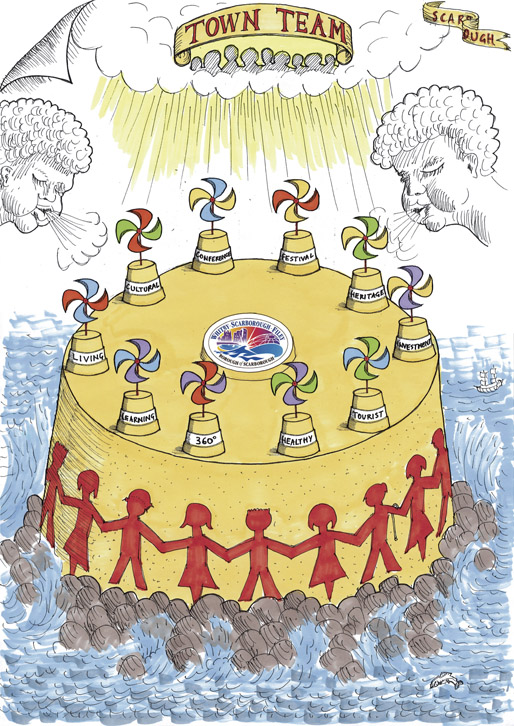

Figure 5.6.4:

The Ten Towns of Scarborough

One unexpected outcome was that local authority officers found themselves free to discuss ideas and were empowered to introduce concepts into the process (previously they had not felt able). Over the following three days, the twenty-seven-strong charrette team analysed and evaluated the outcomes from the two public days. The vision was presented to a large audience at the spa on the evening of Tuesday 30 April. A number of key themes emerged, which identified important areas of consensus. These were to promote the town’s strategic role in the region as a whole; to develop a quality public space strategy; to prioritise the development of flagship projects; to promote a cultural renaissance; to encourage economic development; to create strong, stable and healthy communities and to plan for growth. Throughout the vision-building process, it was acknowledged that Scarborough is a multifaceted town and should be recognised and supported as such. Its ‘ten towns in one’ character defined it as a cultural town, a festival town, a heritage town, a healthy town, a tourist town, a living town, a learning town, an investment town and a 365-day 360-degree town. The vision was neither a rigid plan nor a blueprint – it represented a new direction for the town and its people, and one that was based on shared and positive values and confirmed the need for change, for higher quality, for a new image and for a better environment. As a first step a new Town Team, in association with several Action Teams, was established. This Town Team was given the power, together with Yorkshire Forward and the borough council, to sign off Yorkshire Forward Renaissance funding coming into Scarborough.

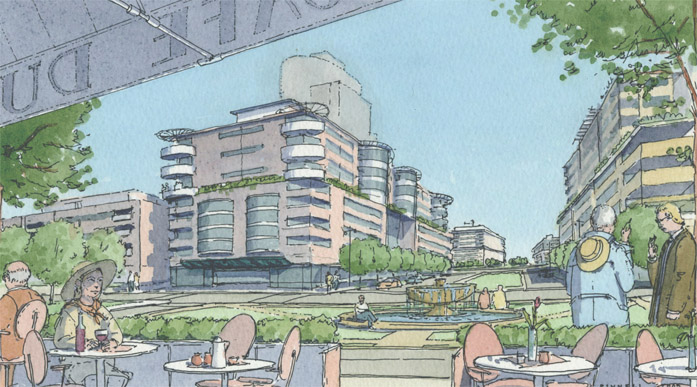

Figure 5.6.5:

Aerial image of the vision for Scarborough Harbour

The Town Team drew up the ‘Scarborough Renaissance Charter’ in the months following the Community Planning Weekend. Town Team members were asked to help define the long-term strategy for Scarborough and clarify the objectives and action points that had been identified. They were asked to ‘leave politics at the door’. An early action, aimed at changing perceptions, was the grassing of St Nicholas Street in front of the Royal Hotel, and a free open-air showing of the movie Little Voice, which was made in Scarborough. A Renaissance Forum was established, meeting monthly with an attendance of between 100 and 150 people. Action Teams were formed, each focusing on a particular area of common interest and developing further key issues that had been identified at the Planning Weekend. A representative from each Action Team was nominated to join the Town Team, which thereby encompassed the interests of the Renaissance Forum as a whole. Fifteen years later, several of these groups continue to meet and discuss their areas of interest. The extensive ‘community animation’ was documented in ‘A Cultural Audit of Scarborough’, which unveiled the potential of the creative community to help drive change. Specific arts-related improvements have since been implemented, including regeneration of the Rotunda Museum, one of the first purpose-built museums in the world, the development of Woodend Creative Workspace with over fifty studio spaces, the restoration of the Scarborough Open Air Theatre, and ongoing arts and cultural festivals. Andrew Clay, director at Woodend, believes that ‘the Arts community feels secure and connected, whereas before people felt isolated – the strong legacy of the process is people being connected and feeling they can make things happen’. Over the years following the charrette, £25m of strategic investment influenced a private sector response of more than £300m investment in the town. This has resulted in the protection or creation of more than 1,000 jobs, an improvement in business relationships and the formation of new industries. An early focus was on the regeneration of the foreshore and harbour, described by Nick Taylor, Scarborough’s Renaissance Manager, as ‘the mantelpiece in the front room of the town’. Diversification of the town’s economy has resulted in a £24m investment in Scarborough’s business park, the construction of a new four-star hotel and an 8 per cent increase in profitability in the visitor economy. The success of Scarborough’s Renaissance has been recognised through a number of prestigious awards, all of which acknowledged the value of the participatory process: Enterprising Britain Awards First Prize (2008); European Enterprise Awards Grand Jury First Prize (2009); International Association for Public Participation’s (IAP2) Project of the Year (2009); Academy of Urbanism Great Town Award (2010). The council and the business community recently partnered to make a successful

competitive bid to national government to fund a new University Technical College (UTC) in Scarborough.

Figure 5.6.6:

Scarborough University Technical College opened in 2016

The UTC opened in September 2016. It is providing skills training for national and local industry, including a new multimillion pound potash mine and the expansion of Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), which is bringing over 1,000 new jobs to the town. Both organisations have sponsored suites at the UTC, enabling students to be job-ready on completion of their education. David Kelly, Scarborough’s Head of Economic Development, believes ‘this would never have happened without the renaissance process fifteen years ago’.Foresight

Vision

Hindsight

5.7 Urridaholt – Daring to be Different

REYKJAVIK, ICELAND

DATE NOVEMBER 2004 CLIENT SECTOR PRIVATE SITE RURAL SCALE NEIGHBOURHOOD VISION PLANNING GREEN DESIGN URBAN DESIGN

A new, walkable neighbourhood on the outskirts of Reykjavik was created, integrating mixed-use development with protected nature. This was the first international project to achieve final certification under the BREEAM Communities Standard 2012.

Iceland is a small island nation situated in the North Atlantic just below the Arctic Circle, with a temperate tundra climate warmed by the Gulf Stream. The country’s economy was severely affected by the global financial crisis in 2008, which caused a depression. The recovery of the economy has been aided by a surge in tourism, with visitors coming to enjoy the country’s unique culture and its volcanic and glacial landscape.

Figure 5.7.1:

View of Urridaholt and Urridavatn Lake

The vast majority of the country’s population of 340,000 live in Reykjavik, which

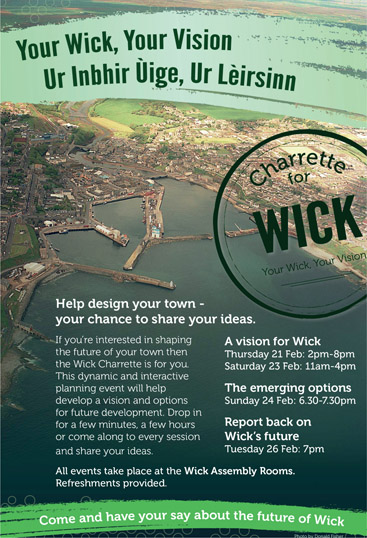

benefits from a ready supply of low-cost, renewable geothermal power. Iceland’s small population has resulted in cheap land and urban sprawl, with large, low-density residential suburbs creating an over-dependence on the car. Gardabær is a small suburban town on the outskirts of Reykjavik, which had been identified for expansion. The identified growth area included Urridaholt, a previously undeveloped hillside adjacent to the pristine Urridavatn Lake. The hill serves as a gateway from the city of Reykjavik to the natural landscape beyond. It rises around 50 m (160 ft) above a lava field, with spectacular views to the mountains, volcanoes and sea. In 2003 the developer of Urridaholt, Jon Palmi Gudmundsson, contacted Halldora Hreggvidsdottir from Alta Consulting, Iceland to ask Alta to do a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). This was intended to evaluate the potential impact of a proposed residential and retail development at Urridaholt on the shallow Urridavatn Lake, and look at how any impacts could be mitigated. Based on the SEA, it was decided to go ahead with the urban expansion, and Alta was asked to project manage the development of a masterplan for Urridaholt and a nearby retail development. The year before, Halldora had worked with John Thompson & Partners (JTP) to run Iceland’s first ever Community Planning Weekend, and she suggested running the same type of charrette process to develop a consensus vision for the development of Urridaholt. An initial charrette was held with council politicians and officers, and included a site visit, briefing, dialogue workshops and hands-on planning design groups. It is typical for Icelandic suburban housing developments to be built out in standard

car-focused street layouts, with uniform low-density residential plots. Three days of collaborative working created a new high-level vision for a walkable, climatically responsive, mixed-use neighbourhood, with the lake and lava protected as much as possible.

Figure 5.7.2:

Sketch of Urridaholt

Following the charrette, ‘Seeing is Believing’ tours were arranged to mixed-use neighbourhoods in Sweden, Denmark, Germany and the UK, and this helped

convince the council to change the municipal plan to allow a mix of uses on the site.

Figure 5.7.3:

Aerial view of the vision for Urridaholt

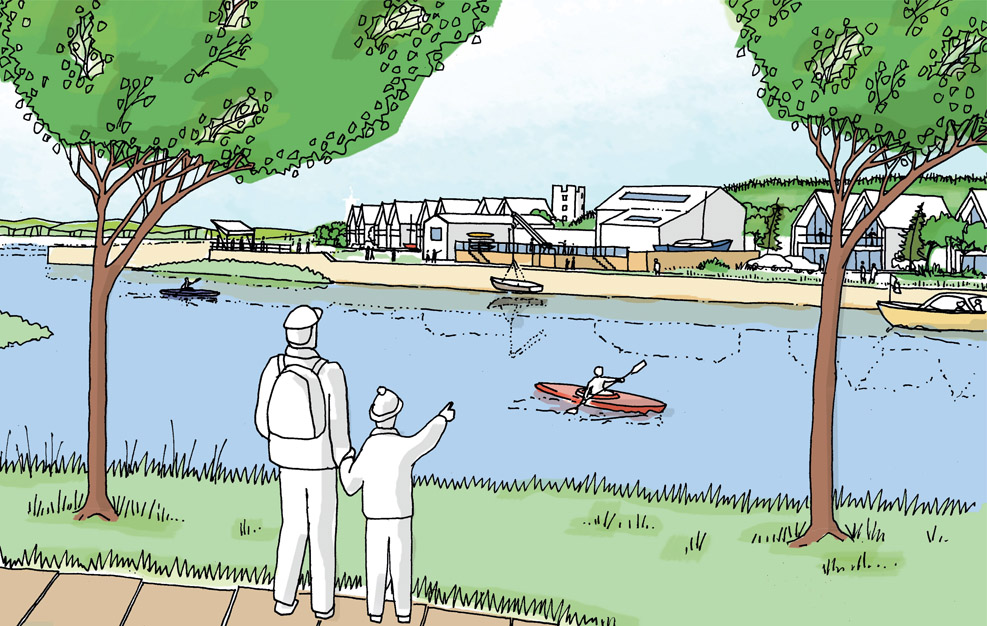

Three months after the initial charrette, in spring 2005, the local community were invited to a Community Planning Weekend, held in a golf club overlooking the site. Participants were introduced to the proposed development concepts and were then invited to take part in workshops, walkabouts and hands-on planning sessions to consider challenges and opportunities for the site. The consensus that emerged through the process was the desire to create a highly sustainable community, with calmed streets and green links to the protected lake and the wider natural environment. Following the public workshops, the consultant team drew up a vision for the site, incorporating ideas from the Winter Cities movement, which was presented back to the community at Gardebær Music Hall. Gunnar Edmondson, current mayor of Gardebær, participated in the whole process: ‘It was very enjoyable to participate and good to see the ambitious approach being taken by the developers and the professionals from the beginning to ensure quality and good placemaking. It is a model for new developments that are now being planned in Gardebær.’ Based on the vision, a masterplan was developed that rejected suburban sprawl typologies in favour of a compact, diverse, mixed-use development. The masterplan focused on environmental and social sustainability, and was closely connected to the natural environment. It included 1,600 residential units, 90,000 m2 (970,000 sq ft) of office and retail space, an elementary school and kindergartens, and up to 65,000 m2 (700,00 sq ft) of space for civic use. Up to 9,000 people will be living and working there when it is fully occupied.

Figure 5.7.4:

Diagram of drainage concept for Urridaholt

Halldora believes that the decision to create a much more sustainable development would have been impossible without a charrette process. ‘Great benefits came from the charrettes – the whole council planning and environmental teams had worked together on a joint vision, and even though new ideas of change emerged, people understood and supported them.’ Participants pointed out the importance of protecting the lake and the cleanliness

of its water. This lead to the introduction of a sustainable urban drainage system (SUDS) in the neighbourhood, as traditional drainage solutions would have resulted in a loss of water catchment and the lake would have disappeared.

Figure 5.7.5:

Urridaholt under construction

This results in some very dominant landscape features, such as green wedges which carry the rainwater down the hill when needed, but also serve as green corridors through the neighbourhood, with walkable paths and vegetation to support natural fauna. This is the first time that SUDS has been implemented in a whole neighbourhood in Iceland, and the consultation assisted greatly. The masterplan was drawn up and an early development phase took place, which included IKEA, but the whole project came to a standstill due to the financial crash in 2008. The development team submitted Urridaholt for BREEAM Communities certification – a method for measuring and evidencing the sustainability of large-scale development plans. The Urridaholt project became the first international project to achieve a final certification under BREEAM Communities 2012, and the first masterplan in Iceland to receive BREEAM Communities certification. It is a 100-hectare (250-acre) development that has achieved an interim certification. The Local Plan for the north side (Phase 2) is the first of the phases in Urridaholt to achieve a final certification, and did so with a Very Good rating. After a five-year pause, development restarted in 2013, and Jon Palmi Gudmundsson recalls: ‘When we reviewed the plan five years after the project was halted, we saw that the emphasis we put on environmental aspects and timeless principles of urban quality had stood the test of time.’ Following the trauma of the financial crash, people in Iceland were looking for a more sustainable model for living.Foresight

Vision

Hindsight

5.8 Former Mill to a Sustainable Neighbourhood

VANCOUVER, CANADA

DATE APRIL 2005 CLIENT SECTOR PRIVATE SITE URBAN SCALE NEIGHBOURHOOD VISION URBAN DESIGN GREEN DESIGN

A vision for a new sustainable neighbourhood, on the site of a former sawmill on the Fraser River, involved a vocal and networked community from Vancouver, where everyone’s favourite sport after hockey is town planning.

Figure 5.8.1:

Hammerhead crane at the Canadian White Pine Mill

The Fraser River was first navigated from its source to the Pacific Ocean in 1808, and over the next 100 years it grew in importance in the lives of the settlers from Great Britain who lived along its banks. Logs were floated down the Fraser to Vancouver, and in the early twentieth century new sawmills were built to process the timber on an industrial scale. In 1926 H. R. MacMillan founded the Canadian White Pine Mill, where massive hammerhead cranes hoisted timber to and from the river. In 1959 the White Pine Mill merged with the neighbouring Dominion Mill and, at its peak in the mid-1960s, the yard’s thousands of workers milled enough timber to build 21,000 homes a year. Then came a period of decline, before the mill finally closed in 2001, with most of the equipment and buildings shipped to New Zealand. In preparation for the site’s regeneration, members of the local community were involved, with the City of Vancouver, in creating the East Fraser Lands Policy Statement. The 53-hectare (130-acre) site was seen as the last neighbourhood-sized development opportunity in the city of Vancouver, and the Policy Statement envisioned a community of around 7,000 homes with a mix of facilities, parkland and a new town centre. The community found the early plans controversial. Concerns included traffic, schools and parks, and uncertainty about the funding of community benefits. Milt Bowling was one of several local community activists who had been working on a local park project. After hearing that Park Lane and Wesgroup were to be the developers, he was keen to meet them and find out how environmental issues were going to be addressed. After work had begun to decontaminate the site, the developers announced that they were planning to commission a charrette to be run by Florida-based New Urbanist practice DPZ in mid-April 2005. Milt recalls: ‘We had been working on the project for three or four years, and we’d never heard of a charrette before, but we thought, “Let’s do it!”’ The week-long charrette process took place in a 300-person capacity tent, erected on the site. The DPZ design team occupied one part of the tent; the remainder provided space for the public workshops. Charrette leader Andrés Duany introduced the process and explained the principles of

sustainable urbanism. He acknowledged the high quality of urban architecture in Central Vancouver, but said that the challenge was to take it to the next level in order to make the project ‘deeply, structurally environmental’.

Figure 5.8.2:

The site at the time of the charrette

The charrette began with a series of community lectures and workshops. These focused on different topics including transportation, environment, parks and recreation, land use and architecture. At times, discussion was heated, and Milt Bowling admitted they were a community who were used to making themselves heard: ‘We put Andrés on the hot seat a lot.’ Meanwhile, the design team worked away at a range of masterplan options, picking up on the discussions from the workshops and bringing in various genres and styles of urbanism. At various points the design team’s masterplans were reported back and discussed with the community.

Figure 5.8.3:

Charrette team working

Figure 5.8.4:

Sketch from the charrette

Figure 5.8.5:

Consented masterplan for River District

Matt Shillito, a planner with the City of Vancouver at the time, recalls: ‘Duany was very good at capturing attention and getting people in the room to consider trade-offs. He would close down topics we had discussed earlier in the week to ensure forward progress was maintained.’ From Day five the design work ramped up to the final presentation on Day seven. Everyone, including Andrés, was surprised that no clear masterplan had emerged, and so five options were presented. All had in common an urban street and block pattern with a high-density town centre and a quality green space network linking to and addressing the Fraser River. Reaction was guardedly positive after the feedback, and it was agreed that having creativity and input early in the process made a difference. The residents found it enjoyable, and one acknowledged that debate had been elevated ‘above the usual nuts and bolts that we talk about’. Following the charrette the design concepts was developed and taken through planning by Vancouver-based James Cheng Architects. Work on site started in 2010, including the construction of the River District Centre and Neighbourhood Restaurant, which was completed in 2011, as an early focus for the new community. At the time of writing, several residential phases to the west of the site are complete, with work on the town centre well under way to the east. The neighbourhoods are boldly high density, with residential buildings facing well-defined streets and public spaces. These have a timeless quality and create a high quality of place for the early residents to enjoy. Referring back to Duany’s challenge to create a ‘project that’s deeply, structurally environmental’, River District has won a range of local, national and international awards for its planning and development processes. Its rainwater management plan and green space strategy will ensure the purity of water running into the Fraser River and the creation of ecological habitats. River District Energy will provide space heating and hot water throughout the neighbourhood, with the capacity to use a variety of renewables and sustainable energy sources. The entire community is on its way to attaining LEED Gold and Built Green Gold status. Milt Bowling remembers that before the charrette took place there were people who were against anything and everything. However, as a representative of the community, he was able to encourage other people to speak calmly and make the most of the opportunity to be involved. Although the community didn’t get everything it had wanted – for example, rule changes subsequently led to a lower requirement for affordable housing – Milt was very positive about the process: ‘The charrette was awesome – you can get the community to agree a vision and I would highly recommend it to any community that wants to be involved.’

Figure 5.8.6:

Completed housing facing the railway

Foresight

Vision

Hindsight

5.9 Alder Hey – The Hospital in a Park

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND

DATE SEPTEMBER 2005 CLIENT SECTOR PUBLIC

SITE URBAN SCALE TOWN VISION PLANNING GREEN DESIGN ARCHITECTURE

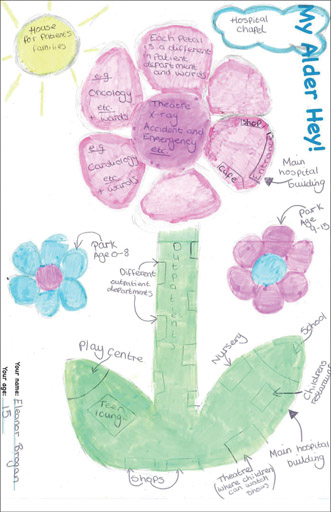

Originally established during the First World War as a US army camp hospital, Alder Hey grew into one of the largest children’s hospitals in the Europe and a world leader in health care and research. After a century, it was time to modernise the facilities and build a new hospital. In October 2015, a radically new children’s hospital building was opened, and a new chapter began in Alder Hey’s history.

Figure 5.9.1:

The original Alder Hey Hospital

In the early 2000s Alder Hey consultant Dr Jane Ratcliffe was inspired by a vision of a ‘hospital in a park … I had this idea that it should be something that’s great fun for young people – a log cabin approach, at one with nature’. This developed into the idea of a hospital with views and access to the neighbouring Springfield Park environment, providing therapeutic benefits to patients and integrated with local neighbourhoods. At that time, however, Liverpool City Council was keen to consider other sites to aid regeneration elsewhere in the city. David Houghton was Alder Hey’s Estates Manager. Having heard Ben Bolgar from the Prince’s Foundation talk about collaborative planning at a conference, he asked Ben to formulate a process for Alder Hey. Ben felt that their typical Sunday to Friday ‘Enquiry by Design’ process was not appropriate for Alder Hey. So after some discussion a step-by-step process was agreed, and the new hospital design concepts emerged through a carefully sequenced charrette process involving professional stakeholders, patients and their parents, and the wider community. The first one-day mini-charrette involved six groups of nine people, including hospital and council representatives, to assess many site options around Liverpool. Most were quickly rejected; six remained. The groups undertook high-level holistic

analyses of each site, followed by a more themed assessment, including looking at transport and environmental issues. Having visited and evaluated each site, Alder Hey emerged as the groups’ clear preferred option.

Figure 5.9.2:

Charrette workshop