1 Global Relevance

Charrettes can work in any community around the world. The case studies demonstrate that successful charrette processes have been run in cultures and places as diverse as Australia and Iceland, China and the Middle East, Canada and Germany, and they prove that culture and context is no barrier to a successful process.

Nevertheless, there are several practical aspects that should be considered. Charrettes should always be run in the local language to ensure local participation is not impeded by the use of a second language. International teams can still lead charrettes when simultaneous translation is provided. The use of sketching and visualisation also overcomes barriers of language and literacy.

For practitioners working in culturally unfamiliar contexts it is essential to undertake social and historical research. Getting to know community leaders first will help this understanding, build trust and give access to the wider community. The potential for preliminary ‘community animation’ work and the number and choice of workshop participants during the charrette may be limited by local political considerations.

2 Scale and Types of Project

Charrettes can be tailored to any scale and type of built environment project, from town or regional planning to neighbourhood revitalisation and the design of buildings.

Charrettes are known for attracting wide public involvement and are programmed to include public and team-working sessions. In some cases, the technical complexity of the project may result in a more specifically structured programme, with communities and professionals coming together at different stages of the process. In Liverpool at Alder Hey, for example, this took the form of distinct workshops for technical experts and the general public, but everything was handled as part of the same overall process, which ensured the integration and the respect of inputs from members of the community.

Where there is no community in and around the site area, or the charrette is organised as a particular method of technical team working, the benefits of cross-discipline, multiday team working on site can still apply.

3 Non Confrontational Exploration of Ideas with Independent Facilitation

Charrettes create a nonconfrontational forum for ideas to be introduced and discussed. The structure of a charrette’s process encourages the rigour of debate within an informal environment through independent facilitation. Workshops never take the form of lectures with facts to be absorbed in silence; rather they are places for suggestions and disagreements, evolving attitudes and changes of mind.

A charrette is a people-focused process, and people can and do differ in outlook and experience. The independence of the facilitators helps the management of the event and allows a process where arguments can arise and be resolved, where difficult development scenarios can be examined. It is a process through which people recognise that a good idea is a good idea and it matters not whether it came from an individual or emerged from group working.

Although the original motivation for a collaborative planning exercise could be a new neighbourhood development proposal such as Gardebær, Iceland or the exploration of a new public realm strategy such as Lübeck, in each instance the freedom of expression allows best practice ideas to be aired and developed. These can take projects into territory that may be unfamiliar to members of the community but result in innovative and leading-edge outcomes, and ultimately more integrated, sustainable solutions.

4 Specific-Issue Charrettes can Catalyse Wider Placemaking Visions

By taking a holistic, placemaking approach to the site concerned, the initial stimulus for the charrette becomes a catalyst for the wider revitalisation of an area and be supported by all. This in turn generates new initiatives and a sense of momentum. In Dunedin, for example, earthquake-strengthening legislation provided the momentum for wider regeneration. New community champions can emerge, and the baton from a single-issue-inspired event is passed on to a much wider audience.

The case studies include charrettes that were held for specific purposes, such as post-tornado recovery (East Nashville), addressing economic decline (Scarborough), agreeing flood protection works (Dumfries) and the introduction of earthquake-strengthening legislation (Dunedin).

5 Commissioning Body – Private, Public, Community

Charrettes are appropriate for private, public and community sector-led projects, and the case studies give examples of charrettes commissioned by all three sectors, such as River District, Vancouver (private), Midland, Perth (public) and Paddington Place, London (community).

Early involvement of the community in projects that will affect their place is important in bringing local knowledge into the process and building support, regardless of who has commissioned the project. It is the focus on ‘Place’ and the people who use it that is key to changing perceptions and creating consensus.

Which body commissions the charrette is likely to have an impact on the budget available, but the case studies demonstrate that charrettes can work effectively when properly organised and resourced, across a full range of budgets.

There are certain directives that should always be followed, such as drafting and publicising a clear mission statement for the charrette, independent facilitation, and an open and transparent process.

6 Politicians and Stakeholders

Planning processes are more than likely at some stage to require the involvement of politicians and statutory organisations. While charrettes are apolitical planning processes, political decision-makers and stakeholders should be communicated with in the early stages of organising a charrette process, so that they are fully briefed about its timing and objectives. This can be done effectively through early meetings or inviting stakeholders to an event to launch the process. It would undermine the process should they hear about it second-hand, perhaps from a constituent or colleague.

Case studies at Caddington and Wick and Thurso show how early working with local politicians and stakeholders helped set the trajectory of the process. In Caddington early political and stakeholder engagement helped ensure effective event organisation and community participation. At Wick and Thurso inviting politicians and stakeholders to the launch event gave the local authority-backed process proactive and widespread media coverage.

The presence and involvement of politicians is usually expected and welcomed by the local community at charrettes, as long as politicians respect the collaborative, consensus-led nature of the process, and do not grandstand or try to score political points.

7 Community Involvement in Organisation

Many of the case studies benefited from the close involvement of members of the community to organise the event itself. The participation of local people at the start ensures the event is appropriately organised, programmed and publicised. Although facilitation by multiskilled professionals is key, the collaborative nature of a charrette allows for the community to be positively engaged and stimulated by the inherent potential of the participatory process.

The best publicity is word of mouth, and excitement can be contagious. At Lübeck, Germany the Unterstützerkreis (steering group) had input into key decisions about the organisation of the process and helped ensure wide publicity throughout the city. The participation of over 400 people in the process led to innovative and well-supported outcomes.

8 Creative Business Communities

It is important to include the local business community and creative sector in the charrette process. This can be difficult – traders and businesspeople often work long hours, and may consider that planning is not relevant to their endeavours. From a practical point of view, it may be necessary to tailor the timing of workshops to suit the working hours of such groups.

However, entrepreneurship and culture is the lifeblood of a healthy community and, as the Scarborough and Dunedin processes demonstrate, active participation by these sectors can create momentum in the process and unexpected investment opportunities. Exploiting specific local artistic talent can enliven a charrette process and emphasise its local distinctiveness, such as in the Blaenau Ffestiniog regeneration.

It may be possible to involve the creative business community in delivering ‘quick wins’, activities or events to generate interest and maintain momentum in a regeneration process, which can take many years to deliver physical results.

There are positive gains to be made by actively involving the creative community in the delivery of short-term projects. These generate excitement and show that change can be positive – and fun. Engagement with local businesses can inspire people to become ambassadors for change. Small steps and low-key initiatives can lead to the creation of thriving and vibrant places.

9 Community Animation

Charrettes are most effective, and valuable, when the resulting consensus vision has involved the widest possible cross-section of the community.

A well-resourced charrette preparation period, such as in Scarborough, helps to animate all sections of the community and lead to wide-ranging participation. Meeting local individuals and groups ahead of the charrette using established networks uncovers local issues, cuts through any scepticism about the process and encourages involvement, ensuring a balanced perspective. Information-gathering is also part of the pre-charrette process, and pre-event gleanings add to the input of local knowledge.

In several case studies, including Santa Fe and Kew Bridge, members of the team spent time getting to know the community and their concerns through both organised and ad hoc meetings. Effort is needed to encourage participation across a wide spectrum of the population, and working with hard-to-reach groups, especially the younger generation, can produce stimulating and unexpected results.

10 Learning and Capacity Building

Charrettes increase knowledge, confidence and capacity building within a community. The workshops can help moderate behaviour, change perceptions and awaken aspirations. Charrettes create a valuable win-win situation, as the outside professionals gain insight from the locals, and locals acquire new knowledge and experience.

Local people know their place well, from a personal perspective, but may have little knowledge of the principles of urban design and how to express often complex ideas. One of the major benefits of holding a charrette is the knowledge exchange that occurs during the public event. The role played by outside facilitators is crucial. They need to pass on technical knowledge and be willing to learn from the community as local experts. This can include formal presentations before and during the charrette including principles of good urbanism, understanding viability, an assessment of the local context, and so on. As a result, local people of all ages and from all walks of life can begin to understand or appreciate the assets of their community in a different way.

11 Dialogue and Feedback Loops

Dialogue and feedback loops are key elements of charrette processes. They enable complex issues to be communicated and debated in order to make decisions and develop effective and supportive solutions, together with a growing awareness that some compromises are necessary. Talking and sketching together helps to ensure that written and drawn solutions reflect the issues and ideas discussed.

At Alder Hey the community allowed building in their park by collaboratively designing a land swap which allowed for a new, reoriented and better-equipped park in the future.

Charrettes help people to prioritise community needs and desires and work out how to achieve them. For example, value-generating uses, such as residential housing, may create funds needed to subsidise community benefits, such as creative workspace or bus services. Cross-funding initiatives can therefore incorporate community aspirations into the vision, but there must be a willingness, on all sides, to have honest and transparent dialogue about the issues and solutions.

The Caterham Barracks charrette is an example of how the community accepted that the facilities they wanted could only be possible if there was an increase in housing, and that this must be well designed and well laid out.

12 Respect and Trust

Most charrette attendees volunteer their time, and the client and facilitation team must accept the essential right of the community to be involved. Local people are experts of the place in which they live and work – they deserve respect. Trust has to be earned and reciprocated. Participants may come from different backgrounds, have very different occupations, even different political leanings, but the process is designed to ensure that single-issue preoccupations take second place to a broad-based vision that is the result of genuine collaboration. Similarly, participants must respect other groups’ and individuals’ views and their right to express them as a starting point for working towards a shared vision.

The professional team members must value community input, whether they agree with it or not. Ideas should be tested, not summarily rejected. Explanations should be provided when suggestions cannot be incorporated in the plans.

At Kew Bridge, a well-organised and previously opposed local community became engaged in a charrette process and design development forums. This led to a redesigned scheme and the delivery of a new gateway development on a site that had been vacant for a long time.

Some development proposals are opposed by communities who begrudge the change to their neighbourhood, over which they feel they have little or no control. This can stoke up negativity and antagonism, sometimes resulting in campaigns and even public demonstrations. An open and transparent charrette process will not automatically dispel the hostility, but it can be effective in bringing people together to build positive consensus visions and action plans, taking account of diverse views.

13 Drawing, Illustration and Models

A charrette differs from traditional consultation meetings and exhibitions because the process includes the physical activity of drawing, in addition to the written and oral activity of discussion workshops.

Although the co-design planning sessions can encourage members of the public to put pen to paper, it is the skill of the facilitator that most often helps tease out and sketch ideas from participants. A suggestion may or may not work when it is drawn on to a plan, but the fact that it has been sketched enables the community to see their ideas immediately and understand the implications of certain decisions. Colour is important, and the simple illustration of water features and areas of green space can help bring a two-dimensional design alive, even to lay-people who may have no experience of urban design.

Once masterplan designs have been worked up in more detail, it can be very useful to build a three-dimensional scale model of the proposed development. This can help people understand the concept of height and mass and show the potential impact of new buildings on surrounding neighbourhoods. In The Liberties in Dublin a model was built of the area following the charrette process and was very effective in helping participants appreciate the scale of development proposals in context.

14 Site Visits and Walkabouts

A charrette is an action-oriented process, not an academic exercise. It should, where possible, include the potential to visit the site, so that participants can see the site through the ‘lens of placemaking’, and observe closely the constraints and opportunities of a specific place. Members of the professional team should be on hand to explain key issues, and participants can gain valuable insight into the site’s context, such as key views and connections. At Caddington in Bedfordshire, the site visits were key for participants to appreciate the character and screened nature of the site.

This practical observation is useful when the team returns to the charrette venue to draw up design options for the site. Adjacent buildings that may be retained are remembered as elements of ‘setting’, and roads which are usually driven down in a journey from A to B take on a totally different significance when viewed in terms of access to a site.

15 Follow-Up

The collaborative and stimulating nature of a charrette creates a sense of momentum and raises expectations, which need to be managed positively. Some process ‘follow-up’ should be planned and resourced before the charrette takes place, so that members of the community, who have often invested considerable personal time and effort in the process, do not feel let down.

Public sector planning and regeneration projects in particular can take a long time to deliver results, and communities will need patience. But if time passes and nothing happens, patience may be replaced by anger and frustration.

‘Early win’ and ‘meanwhile’ or ‘interim’ projects, sometimes known as pop-up or tactical urbanism, are useful ways to keep projects alive and build confidence that the process can deliver results. The fact that the local vet could move temporarily into a barrack block while the Caterham Village was being developed was a visible reminder of the original charrette.

In Scarborough a Town Team was set up whose first task was the development of a charter to embed the principles of the charrette into a document signed up to by the town.

Involvement in creating design codes, for example, can help remind people that they still have a role to play in the development process, however distant the delivery.

16 Valuable Memories

Communities that have been through a charrette process often retain a strong memory of the experience as a special time when people came together in the spirit of collaboration at the birth of the project. The vision becomes a tangible expression of the process itself.

The fact that it is an intensive event adds to the uniqueness of the memory. People who were strangers at the first workshop can become firm friends by the time of the report back, a week or so later. Knowledge is acquired, unexpected skills are developed, and community champions emerge to help take the project forward.

At Midland, Perth the original vision is regularly referred to some twenty years later, and held firmly in mind by both the community and the Redevelopment Authority.

17 Not Reverting to Top-Down Approaches, Remaining Participative

There is always a danger that a development team may choose to revert to a traditional closed planning process, even after a charrette has been successfully held earlier in a process. This could be due to various factors, including staff changes, or because it is considered that a charrette approach would take too long. A community will resent the change of style if they have already experienced an open, collaborative way of working. This can lead to conflict and delay, and it is undoubtedly a short-sighted approach.

At Alder Hey a later stage of the planning of the scheme’s residential areas was developed without a charrette and resulted in opposition to a scheme from a community that had been very supportive of the earlier phases, and were indeed actively and positively involved in delivering the new park as part of the scheme.

18 Project Delivery and Governance

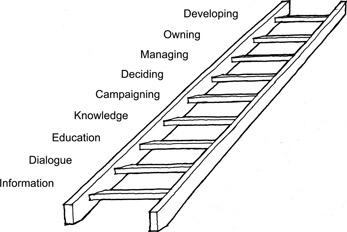

A natural follow-on from community participation in charrette processes is the involvement of local communities in the further development of proposals and the eventual delivery, ownership and management of sustainable and locally responsive community assets. A revised version of Sherry Arnstein’s ladder of participation by John Thompson illustrates the successive stages that people can move through to reach the point where they feel truly identified with and in control of neighbourhood decision making.

Organisations are being established globally following charrettes to enable the continuing involvement of the community in project design, budgeting, delivery and management. Structures include Community Forums, Town Teams, Community Trusts Community Land Trusts and parish and town councils. Community Land Trusts are becoming increasingly important methods of delivering affordable enterprise space, community facilities and housing. At Caddington Woods, for example, a new Community Trust will own and manage over forty homes, a community building and the open spaces and woodland as well as providing a new bus service linking to the local town and villages.

19 Spreading the Word

Charrettes remain a surprisingly non-mainstream way of working, despite their emergence fifty years ago as a proven and valuable aid to planning and design. Perhaps this is because they have never received the mainstream political and media attention they deserve. Maybe there are not enough skilled professionals to facilitate processes. Or perhaps planners are threatened by a process that challenges the status quo.

Charrettes encourage dialogue, clarity and transparency of purpose. Those who have organised them, or who have experienced their benefits, need to be encouraged to promote them – by speaking at conferences, submitting award nominations, writing articles and books, and lobbying politicians.

The rise of social media and blogging could be a way for stories of successful charrettes to reach a new audience. The aim must be to spread the word to the wider community, to awaken debate, to generate commissions and to inspire confidence in the value of a collaborative and participatory planning process.

20 Changing Lives and Careers

The case studies involved a number of participants who readily acknowledged the impact the process had on shaping their lives and future careers, from a professional perspective or through community activism and taking on responsible roles.

In Nashville and Santa Fe the architects are still very much involved in the long-running regeneration processes, and in the minds of the community are linked with the project.

At Caddington a former community activist, now councillor, has a role on the Community Trust established to deliver affordable housing, environmental management and a new bus service from the site.

Figure 6.1:

Ladder of participation

Vignette from Kew Bridge charrette