2

International Networks of Early Digital Arts

Darko Fritz

The histories of international networks that transgressed Cold War barriers and were involved with digital arts in the 1960s and early 1970s are, in many respects, an under-researched subject. The following tells a short, fragmented history of networks of digital art—that is, organizations that group together interconnected people who have been involved with the creative use of computers. Criteria used for the inclusion of these networks are both the level of their international activities and the duration of the network, which had to operate for longer than a single event in order to qualify. Educational networks mostly had a local character, despite the fact that some of them involved international subjects or students, and created clusters of global unofficial networks over time.1

There are many predecessors to today’s international art-science-technology networks, alliances that were primarily science- and technology based but that understood culture in a broader sense. Some of them reshaped world culture regardless of and beyond their primary mission and goals. The brief history and success story of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and its Computer Society may function as a case study of a network’s continuing growth over a century and a half, a dream come true for a capitalist economy. I will describe IEEE and a few other networks of digital arts, using text excerpts from their original documents, including official homepages, and adding critical comments by others and myself.

The IT Sector as Capitalist Dream of Growth

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers is a US network that transgresses national borders and became an international community of interest. Its growth and history are a reminder of the rapid evolution of technological innovations over the last century and a half that reshaped first Western and later world culture in many respects. Looking at its history provides a basis and interesting background for an examination of digital art networks.

Back in the 1880s electricity was just beginning to become a major force in society. There was only one major established electrical industry, the telegraph system, which—in the 1840s—began to connect the world through a communications network “faster than the speed of transportation” (IEEE 2013). The American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE) was founded in New York in 1884 as an organization “to support professionals in their nascent field and to aid them in their efforts to apply innovation for the betterment of humanity” (IEEE 2013). Many leaders and pioneers of early technologies and communications systems had been involved in or experimented with telegraphy, such as Western Union’s founding President Norvin Green; Thomas Edison, who came to represent the electric power industry; and Alexander Graham Bell, who personified the newer telephone industry. As electric power spread rapidly—enhanced by innovations such as Nikola Tesla’s AC induction motor, long-distance alternating current transmission, and large-scale power plants, which were commercialized by industries such as Westinghouse and General Electric—the AIEE became increasingly focused on electrical power.

The Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE), founded in 1912, was modeled on the AIEE but devoted first to radio and then increasingly to electronics. It too furthered its profession by linking its members through publications, the development of standards, and conferences. In 1951 IRE formed its Professional Group on Electronic Computers. The AIEE and IRE merged in 1963 to form the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, or IEEE. At the time of its formation, the IEEE had 150,000 members, 140,000 from the United States and 10,000 international ones. The respective committees and subgroups of the predecessor organizations AIEE and IRE combined to form the modern IEEE Computer Society.2 The Computer Group was the first IEEE subgroup to employ its own staff, which turned out to be a major factor in the growth of the society. Their periodical, Computer Group News, was published in Los Angeles and, in 1968, was followed by a monthly publication titled IEEE Transactions on Computers. The number of published pages in these periodicals grew to about 640 in the Computer Group News and almost 9700 in the Transactions. By the end of the 1960s membership in the Computer Group had grown to 16,862, and, in 1971, it became the Computer Society. The Computer Group News, renamed Computer in 1972, became a monthly publication in 1973, and significantly increased its tutorial-based content. By the end of the 1970s, Computer Society membership had grown to 43,930. The society launched the publications IEEE Computer Graphics & Applications in 1981; IEEE Micro in 1981; both IEEE Design & Test and IEEE Software in 1984; and IEEE Expert in 1986. IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering (introduced in 1989) and IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis & Machine Intelligence moved from bimonthly to monthly publication in 1985 and 1989, respectively. The society sponsored and cosponsored more than fifty conferences annually, and the number of meetings held outside the United States, many of them sponsored by technical committees, grew significantly over the years. In the 1980s the society sponsored and co-sponsored more than ninety conferences outside the United States. In 1987 CompEuro was initiated, and by the end of the 1980s, 56 standards had been approved and 125 working groups, involving over 5000 people, were under way. In the new political and economic climate after the (un)official end of the Cold War, the Central and Eastern European Initiatives, as well as committees in Latin America and China, were formed (1990s).

As new areas and fields in information processing were developed, the society added new journals to meet the demands for knowledge in these subdisciplines: Transactions on Parallel & Distributed Systems (1990); Transactions on Networking, jointly launched with the IEEE Communications Society and ACM SIGCOM (1991); Transactions on Visualization & Computer Graphics (1995); and Internet Computing (1997) and IT Professional (1999). By the end of the 1990s IEEE Computer Society was publishing twenty-four journals and periodicals, and the total number of editorial pages published had risen to 70,661 in 1999. The 1990s also were the decade that saw the coming of age of the Internet and digital publications, and the IEEE Computer Society’s digital library was first introduced in 1996 in the form of a set of CDs of 1995 periodicals. Soon afterwards, this set was posted on the Web, and, in 1997, the IEEE Computer Society Digital Library (CSDL) was formally launched as a product. Toward the end of the 1990s, the Computer Society had a staff of over 120. In addition to the Washington headquarters and the California publication office, the Society opened offices in Tokyo and Budapest, Moscow and Beijing. The Society’s relationship with the IEEE also changed; while it had previously operated fairly independent of the IEEE, it now became more integrated into it. A whole set of new publications was launched: IT Professional, IEEE Security and Privacy, IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, IEEE Pervasive Computing, IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, IEEE Transactions on Haptics, IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, IEEE Transactions on Services Computing, IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biology, and IEEE Transactions on Nanobiosciences. In some cases these publications were developed in collaboration with other IEEE societies. In the 2010s, the Computer Society was involved in close to 200 conferences a year, and increasingly became a conference and proceedings service for other IEEE Societies. In the early 21st century, IEEE comprised 38 societies; published 130 journals, transactions, and magazines; organized more 300 conferences annually; and had established 900 active standards. IEEE today is the world’s largest technical professional society. The history of IEEE is the realization of a capitalist, market-driven dream of everlasting growth.

The Emergence of Digital Arts and Related Networks

If we examine the histories of the ever-changing currents of modern and contemporary arts’ and culture’s interests over the last century and a half, we cannot trace such a continuing growth and such massive figures, especially not in the field of digital arts and the related blending of art-science-technology. The streams of rationality and specific methodologies that are embodied, in different ways, in art-science-technology practices, digital arts, and other forms of media art constantly came in and out of focus within the major streams of modern and contemporary art, a trend that is continuing up to the present. Only computer-generated music, under the umbrella of electronic music, has a continuous history of production, institutions, and education that continues without breaks over the decades and is still an active field today. In sound and text-based arts, we can continuously trace the creative use of computers since the 1950s.

Several initiatives that had started exploring the relationship between art, science, and technology in the 1960s shifted their focus toward the use of digital technologies by the end of the decade. In the beginning of the 1960s, a majority of art practitioners (artists, art historians, and theoreticians) shared an approach to “machines” that did not differentiate much between mechanical and information process machines, as will be seen in the following discussion of the practices of both New Tendencies (1961–1973) and Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T., since 1967). In the late 1960s digital art became the focus of several art exhibitions and expanded theoretical discourse, which resulted in the creation of new networks dedicated to digital arts.

After a series of smaller solo exhibitions and local gallery presentations starting in the mid-1960s, the first international group exhibition dedicated exclusively to computer-generated art was held at Brno in the Czech Republic in February 1968. That show, as well as a series of international group exhibitions on cybernetics and computer art that took place the following year, were organized by major art institutions and presented across Europe, the United States, and Japan, with some of them traveling around the world.3 This presence within the structures of cultural institutions fueled both the professional and mainstream imagination and created both an artistic trend and a certain hype surrounding imaginary futures that most radically presented itself at the world fairs of that time. There suddenly seemed to be a necessity for international networks for digital arts that would transgress the exhibition format and fulfill the need for networking on a regular rather than just occasional basis.

Lacking their own networks, digital art practitioners originally participated in information technology ones and their annual conferences. Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) held presentations at the annual meeting of the IEEE in 1967 (Figure 2.1). Digital art was presented at the International Federation for Information Processing (IFIP; since 1960) and the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) and their Special Interest Group on Graphics and Interactive Techniques (SIGGRAPH; since 1974). Next to their core focus on information technology (IT) industry and business, both IFIP and ACM/SIGGRAPH hold competitions and awards for digital arts that often focus more on technical excellence than artistic and cultural achievements and development of critical discourse. The critique of these mainstream IT industries for their lack of critical discourse and social awareness was common among the practitioners with a background in humanities, art, and culture.

Figure 2.1 Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) at the annual meeting of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), March 20–24, 1967, Coliseum and Hilton Hotel, New York. Artists Tom Gormley and Hans Haacke are talking to an engineer.

Courtesy: Experiments in Art and Technology. Photography: Frank Grant.

IFIP, an umbrella organization for national societies working in the field of information processing, was established in 1960 under the auspices of UNESCO as a result of the first World Computer Congress held in Paris in 1959. Today the organization represents IT Societies from fifty-six countries or regions, with a total membership of over half a million. IFIP links more than 3500 scientists from academia and industry—organized in more than 101 Working Groups reporting to thirteen Technical Committees—and sponsors 100 conferences yearly, providing coverage of a field ranging from theoretical informatics to the relationship between informatics and society, including hardware and software technologies, as well as networked information systems. In the 1960s IFIP conferences provided space for much needed international networking of the digital arts community. An important meeting and networking point was the 1968 IFIP Congress in Edinburgh, where the art networks Computer Arts Society UK and Netherlands were both initiated and started their collaboration.

ACM, the first association for computing, was established in 1947, the year that saw the creation of the first stored-program digital computer, and has been organizing an annual Computer Arts Festival since 1968. ACM’s Special Interest Groups (SIGs) in more than thirty distinct areas of information technology address interests as varied as programming languages, graphics, human–computer interaction, and mobile communications. SIGGRAPH, the Special Interest Group on Graphics and Interactive Techniques, is the annual conference on computer graphics convened by the ACM since 1974. SIGGRAPH conferences have been held across the United States and attended by tens of thousands of computer professionals. The papers delivered there are published in the SIGGRAPH Conference Proceedings and, since 2002, in a special issue of the ACM Transactions on Graphics journal. ACM SIGGRAPH began their art exhibitions with Computer Culture Art in 1981, presenting computer graphics, which developed into a survey of interactive and robotic art titled Machine Culture in 1993. SIGGRAPH established several awards programs to recognize contributions to computer graphics, among them the Steven Anson Coons Award for Outstanding Creative Contributions to Computer Graphics that has been awarded bi-annually since 1983 to recognize an individual’s lifetime achievement.

At the other end of the spectrum was the art and culture scene established by socially critical art groups around the world that criticized the art market and cultural industry and power structures in general. The different attitudes toward the IT sector represented by the culture and industry positions, respectively, became explicit in the ACM Counter-Conference in Boulder4 that was held in parallel to the 1971 National Conference of the ACM in Chicago. An anonymous comment in the PAGE bulletin of the Computer Arts Society London read: “These two meetings will mark a climax in the campaign for social responsibility in the computer profession. Their repercussions will be felt for years to come” (PAGE 1971).

The critique came from the Computer Arts Society (CAS), founded in 1968 by Alan Sutcliffe, George Mallen, and John Lansdown as the first society dedicated to digital arts in order to encourage the use of computers in all art disciplines. Over the next few years CAS became the focus of computer arts activity in Britain, supporting practitioners through a network of meetings, conferences, practical courses, social events, exhibitions and, occasionally, funding. It ran code-writing workshops, held several exhibitions, and produced the news bulletin PAGE (1969–1985), edited by Gustav Metzger and focused on recent events and initiatives. Its first exhibition in March 1969, Event One, employed computers as tools for enhancing the production of work in many fields, including architecture, theater, music, poetry, and dance (Mason 2008). By 1970 CAS had 377 members in seventeen countries. The spin-off organization Computer Arts Society Holland (CASH) was initiated by Leo Geurts and Lambert Meertens and held its first meeting in Amsterdam in 1970. Ten out of its thirty-four attendants were creatively involved in the arts (visual art, music, design, literature) and nine more from a theoretical or museological perspective (art history, art criticism, musicology, museum). Sixteen of the participants had experience working with computers (Wolk 1970). Recognizing computer literacy as an essential challenge for participants coming from the arts and humanities, CASH organized programming courses at Honeywell Bull venues in Amersfoort and The Hague. The access to computers was made possible as well, by means of time-sharing computer systems, enabling users with backgrounds in humanities and arts to use computers for the first time. Leo Geurts and Lambert Meertens edited two issues of the PAGE bulletin that presented new developments in the Dutch scene in 1970 and 1971.

An American branch, CASUS, was formed in 1971. PAGE no. 22 from April 1972 was co-edited by Kurt Lauckner of Eastern Michigan University, who was coordinator of CASUS, and Gary William Smith of Cranbrook Academy of Art, who was US chairman of the visual arts. The US chairman of Music Composition was David Steward, coming from the Department of Music of Eastern Michigan University (Ypsilanti, Michigan) where Lauckner was at the Mathematics Department. “Due to both the visual as well the verbal nature” (PAGE 1972), the proceedings of the First National Computer Arts Symposium, held at Florida State University, was made and distributed as eight and a half hours video tape, instead of print.

In 1969 the first meeting of “De werkgroep voor computers en woord, beeld en geluid” (Working group for computers and verbal, visual and sonic research) was held at the Institute of Art History of Utrecht University in the Netherlands. It was primarily a platform for information exchange between those who were pioneering in the use of computers in different fields on both a national and international level. Art historian Johannes van der Wolk, who edited, self-published, and distributed eleven newsletters of the working group written in Dutch, handled the organization of the group all by himself. The working group wasn’t a formal organization, and Wolk’s private address was used as contact. One hundred and fifty-five articles in total were published in the newsletters. Subscribers were considered members in the group and, by 1972, the mailing list comprised 126 subscribers, 92 from the Netherlands and 34 from abroad. Members participated by providing information for publication, and shaped the newsletter’s content via replies to questionnaires. Following the distribution of a questionnaire regarding expressions of interest, an issue presented thirty-eight responses, of which ten were related to arts and creativity (Wolk 1971). Van der Wolk initiated both symposia of the Dutch Working Group for computers and verbal, visual, and sonic research that were held in Deft and Amsterdam in 1970.

In 1967, Robert Hartzema and Tjebbe van Tijen founded the Research Center Art Technology and Society in Amsterdam, which lasted until 1969. The center published two reports, the first on the necessity of improving connections between the categories of artists, designers, and cultural animators, on the one hand, and engineers, technicians, and scientists, on the other; the second on the discrepancy between the economic and cultural development of science and technology versus art, noting a one-sided growth of the science/technology sector with art lagging behind (van Tijen 2011). The first stage of the Research Center was organized out of offices in the Sigma Center, Amsterdam. Later the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam housed the project for over a year. In 1968 and 1969 a series of conferences organized by the Research Center was held at the Museum Fodor, Amsterdam. In 1968 the Research Center’s co-founder Tjebbe van Tijen, together with Nic Tummers, wrote a manifesto and campaigned against the World Fair Expo ’70 in Osaka for over a year, calling for a debate about the function of world fairs and the role of artists, designers, and architects in these undertakings. The manifesto critiqued the inauguration of national pavilions in the world fair after an initial expression of architectural unity, and called for resistance to the overall concept:

Don’t the World’s Fairs force themselves upon us as manifestations of the “freedom” to have to produce things for which there is no need and to have to consume what we were forced to produce? Don’t artists, designers and architects give the World Fairs a “cultural image” and aren’t they being (mis)used to present a sham freedom?

(van Tijen and Tummers 1968)

The manifesto was distributed internationally, often inserted in art magazines supportive of its cause. People were asked to start a debate in their own circles and send reactions back to the manifesto’s authors. Dutch architect Piet Blom finally refused the invitation to participate in the world fair. Events around the Expo ’70 marked a local turning point, dividing the Japanese art scene into pro and contra Expo ’70 and influencing developments of media art in Japan that would later be criticized for their supposed non-criticality—Japanese “device art,” the art of the electronic gadgets, being an example. Machiko Kusahara puts these developments into historical and local perspective:

following the 1963 decision to realize Osaka Expo ’70, experimental artists and architects were invited to design major pavilions to showcase latest media technologies. However, Expo was criticized as a “festival” to draw public attention away from US–Japan Security Treaty to be renewed in 1970. Avant-garde artists had to make a decision. Some leading artists left Japan and joined FLUXUS in New York. Some joined anti-Expo movement. Others (GUTAI, Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, Arata Isozaki and others) stayed and supported the huge success of Expo. They remained the main stream in Japanese media art. The collaboration system between artists and the industry for Expo became a tradition since then.

(Kusahara 2007)

E.A.T. did not join in the criticism, but used Expo ’70 as an opportunity to realize some of their ideas about the integration of art and technology through their work on the Pepsi pavilion. E.A.T. was conceived in 1966 and founded as a non-profit organization by engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer and artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman in New York in 1967. Its focus was on the involvement of industry and technology with the arts and the organization of collaborations between artists and engineers through industrial cooperation and sponsorship. Klüver’s vision was that “The artist is a positive force in perceiving how technology can be translated to new environments to serve needs and provide variety and enrichment of life” (Klüver and Rauschenberg 1966). In 1967, the E.A.T. expressed their goal to:

Maintain a constructive climate for the recognition of the new technology and the arts by a civilized collaboration between groups unrealistically developing in isolation. Eliminate the separation of the individual from technological change and expand and enrich technology to give the individual variety, pleasure and avenues for exploration and involvement in contemporary life. Encourage industrial initiative in generating original forethought, instead of a compromise in aftermath, and precipitate a mutual agreement in order to avoid the waste of a cultural revolution. (Klüver and Rauschenberg 1967)

E.A.T.’s positive, fairly non-critical, and supportive attitude toward corporations and industry becomes evident in their mission statement:

to assist and catalyze the inevitable active cooperation of industry, labor, technology and the arts. E.A.T. has assumed the responsibility of developing an effective method for collaboration between artists and engineers with industrial sponsorship.

The collaboration of artist and engineer under industrial sanction emerges as a revolutionary contemporary process. Artists and engineers are becoming aware of their crucial role in changing the human environment and the relevant forces shaping our society. Engineers are aware that the artist’s insight can influence his direction and give human scale to his work, and the artist recognizes richness, variety and human necessity as qualities of the new technology.

The raison d’être of E.A.T. is the possibility of a work which is not the preconception of either the engineer, the artist or industry, but the result of the exploration of the human interaction between these areas.

(Klüver and Rauschenberg 1967)

Gustav Metzger commented on the E.A.T. collaboration with the industry in 1969: “The waves of protest in the States against manufacturers of war materials should lead E.A.T. to refuse to collaborate with firms producing napalm and bombs for Vietnam,” and continues, “Forty-five professors at the M.I.T. have announced a one-day ‘research stoppage’ for March 4 in protest against government misuse of science and technology” (Metzger 1969).

E.A.T. arranged for artist visits to the technical laboratories of Bell, IBM, and RCA Sarnoff, all located in the United States.5 By 1969 the group had over 2000 artist and 2000 engineer members. They implemented a database “profiling system” to match artists and engineers according to interests and skills. A “Technical Services Program” provided artists with access to new technologies by matching them with engineers or scientists for one-on-one collaborations on the artists’ specific projects. E.A.T. was not committed to any one technology or type of equipment per se. The organization tried to enable artists to directly work with engineers in the very industrial environment in which the respective technology was developed. Technical Services were open to all artists, without judgment of the aesthetic value of an artist’s project or idea. E.A.T. operated in the United States, Canada, Europe, Japan, and South America, and about twenty local E.A.T. groups were formed around the world.

In 1966 E.A.T. organized a series of interdisciplinary events titled 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering in New York, which involved ten artists, musicians, and dancers; thirty engineers; and an audience of 10,000. Despite the fact that the (mostly analog) technology did not work properly most of the time, which led to bad publicity, these events gained a reputation as milestones in live technology-based arts. In 1968, once again in New York, E.A.T. participated in the organization of a major exhibition on art and science titled The Machine, as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which featured 220 works by artists ranging from Leonardo da Vinci to contemporary ones. E.A.T. proposed a “competition for the best contribution by an engineer to a work of art made in collaboration with an artist” (Vasulka 1998), judged by a panel consisting of engineers only, and organized a related exhibition with the title Some More Beginnings at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, the same year.

E.A.T. then went on to organize artist–engineer collaborations working on the design and program of the Pepsi-Cola Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka. Twenty artists and fifty engineers and scientists contributed to the design of the pavilion. Digital technologies were used in some of the works resulting from this collaboration. From 1969 to 1972 E.A.T. also realized a series of socially engaged, interdisciplinary projects that made use of user-friendly analogue telecommunication systems in the United States, India, Japan, Sweden, and El Salvador.

In 1980 E.A.T. put together an archive of more than 300 of the documents it had produced: reports, catalogues, newsletters, information bulletins, proposals, lectures, announcements, and press covers. Complete sets of this archive were distributed to libraries in New York, Washington, Paris, Stockholm, Moscow, Ahmadabad, and London, illustrating E.A.T.’s understanding of a globalized cultural network, as well their care in preservation and archiving.6

E.A.T. has been an important initiative that, in a constructive and positivist manner, supported collaborations between artists and engineers in the literal sense, by bringing them together. As its value system was not artistic or cultural but quantitative only, some non-critical projects and unequal collaborations took place next to successful ones. E.A.T. considered digital technologies as one of the available technologies at the time, with no particular focus on them. After being criticized for its lack of social responsibilities in its undertakings for Expo ’70, E.A.T. changed course and realized a series of socially engaged projects using analogue technologies. Some projects took place in underdeveloped countries, putting E.A.T. ahead of its time in its understanding of a technology-driven globalized world. E.A.T. bridged the industrial and information society of the 1960s and 1970s through different projects that placed the machine at the center of creative impulses, questioning basic notions of life (of humans and machines) and communication amongst humans.

Bridging Analog and Digital Art in New Tendencies

In a different cultural context New Tendencies started out as an international exhibition presenting instruction-based, algorithmic, and generative art in Zagreb in 1961, and then developed into an international movement and network of artists, gallery owners, art critics, art historians, and theoreticians. Adhering to the rationalization of art production and conceiving art as a type of research theoretically framed by people such as Matko Meštrović, Giulio Carlo Argan, Frank Popper, and Umberto Eco, among others (Eco 1962; Meštrović 1963; Argan 1965, Popper 1965), New Tendencies (NT) was open to new fusions of art and science. NT from the very beginning focused on experiments with visual perception that were based on Gestalt theory7 and different aspects of “rational” art, which involved the viewer in participatory fields of interaction: for example, arte programmata, lumino-kinetic art, gestalt kunst, neo-constructivist and concrete art; all of the aforementioned were later subsumed under the collective name NT or simply visual research. From 1962 onward New Tendencies acted as a bottom-up art movement without official headquarters, experimenting with new ways of organization in the form of a decision-making system that involved the collective in different organizational forms, which would change over time. Between 1961 and 1973 the Gallery of Contemporary Art organized five NT exhibitions in Zagreb; in addition, large-scale international exhibitions were held in Paris, Venice, and Leverkusen. The movement was truly international, both transcending Cold War blocs and including South American and, at a later point, Asian artists. This scenario, unique in the Cold War context, was possible due to Zagreb’s position in then socialist but non-aligned Yugoslavia. From 1961 to 1965 New Tendencies both stood for a certain kind of art and acted as an umbrella or meta-network for approximately 250 artists, critics, and art groups. The latter included, among others, Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV) from France; Equipo 57 from Spain; Gruppo di ricerca cibernetica, Gruppo MID, Gruppo N, Gruppo T, Gruppo 63, Operativo R, and Azimuth from Italy; Zero from Germany; Art Research Center (ARC) and Anonima Group from the United States; and Dviženije from the USSR.

Part of the NT aesthetics was quickly adopted, simplified, and commercialized by mainstream cultural industries and became known as op art (optical art) by the mid-1960s, a point in time that could already be seen as the beginning of the end of New Tendencies as an art movement. Having cultivated a positive attitude toward machines from the beginning, New Tendencies adopted computer technology via Abraham Moles’s information aesthetic (Moles 1965). Its organizers saw this as both a logical progression of New Tendencies and another chance of keeping the rational approach to art on track while body art, land art, conceptual art, and other new contemporary art forms took center stage in the artworld, and, to a large extent, overshadowed or even excluded the previously developed language of concrete art. The new interest in cybernetics and information aesthetics resulted in a series of international exhibitions and symposia on the subject computers and visual research, which now took place under the umbrella of the rebranded tendencies 4 (t4, 1968–1969) and tendencies 5 (t5, 1973) events, after the prefix “new” had been dropped from the name in 1968. Brazilian artist and active NT participant Waldemar Cordeiro’s statement that computer art had replaced constructivist art8 can be traced through the histories of both [New] Tendencies networks themselves.

The years 1968 to 1973 were the heyday of computer-generated arts not just in Zagreb but around the world; computer arts started to be distinguished from other forms of media and electronic arts. As has always been the case in the field of media arts, a technologically deterministic and techno-utopian discourse, on the one hand, and a critically minded and techno-dystopian one, on the other, coexisted.

On May 5, 1969, at the symposium in Zagreb, art critic Jonathan Benthall from London read the Zagreb Manifesto he had coauthored with cybernetician Gordon Hyde and artist Gustav Metzger, and whose opening line was: “We salute the initiative of the organizers of the International Symposium on Computers and Visual Research, and its related exhibition, Zagreb, May 1969.” The following line identified the “we” of the opening sentence: “A Computer Arts Society has been formed in London this year,9 whose aims are ‘to promote the creative use of computers in the arts and to encourage the interchange of information in this area’” (Hyde, Benthall, and Metzger 1969).

The manifesto goes on to state that “It is now evident that, where art meets science and technology, the computer and related discipline provide a nexus.” The conclusion of the Zagreb Manifesto is pregnant with ideas that circulated at the end of the 1960s and may be reconsidered today as still contemporary issues:

Artists are increasingly striving to relate their work and that of the technologists to the current unprecedent(ed) crisis in society. Some artists are responding by utilizing their experience of science and technology to try and resolve urgent social problems. Others, researching in cybernetics and the neuro-sciences, are exploring new ideas about the interaction of the human being with the environment. Others again are identifying their work with a concept of ecology which includes the entire technological environment that man imposed on nature. There are creative people in science who feel that the man/machine problem lies at the heart of the computer the servant of man and nature. Such people welcome the insight of the artist in this context, lest we lose sight of humanity and beauty.

(Hyde, Benthall, and Metzger 1969)

At the same symposium, Gustav Metzger—co-author of the Zagreb Manifesto and at the time an editor of the PAGE bulletin published by the Computer Arts Society from London—took the critical stance a step further while calling for new perspectives on the use of technology in art: “There is little doubt that in computer art, the true avantgarde is the military” (Metzger 1970).10 He later elaborated on one of his own artworks—a self-destructive computer-generated sculpture in public space—for which he presented a proposal at the tendencies 4—computers and visual research exhibition that ran in parallel to the symposium of the same title (Figure 2.2). It was one of the rare moments in the 1960s when one socially engaged international network surrounding computer-generated art communicated with another one in a fruitful manner. At the time, the scope of interests of CAS London and [New] Tendencies Zagreb was largely the same.

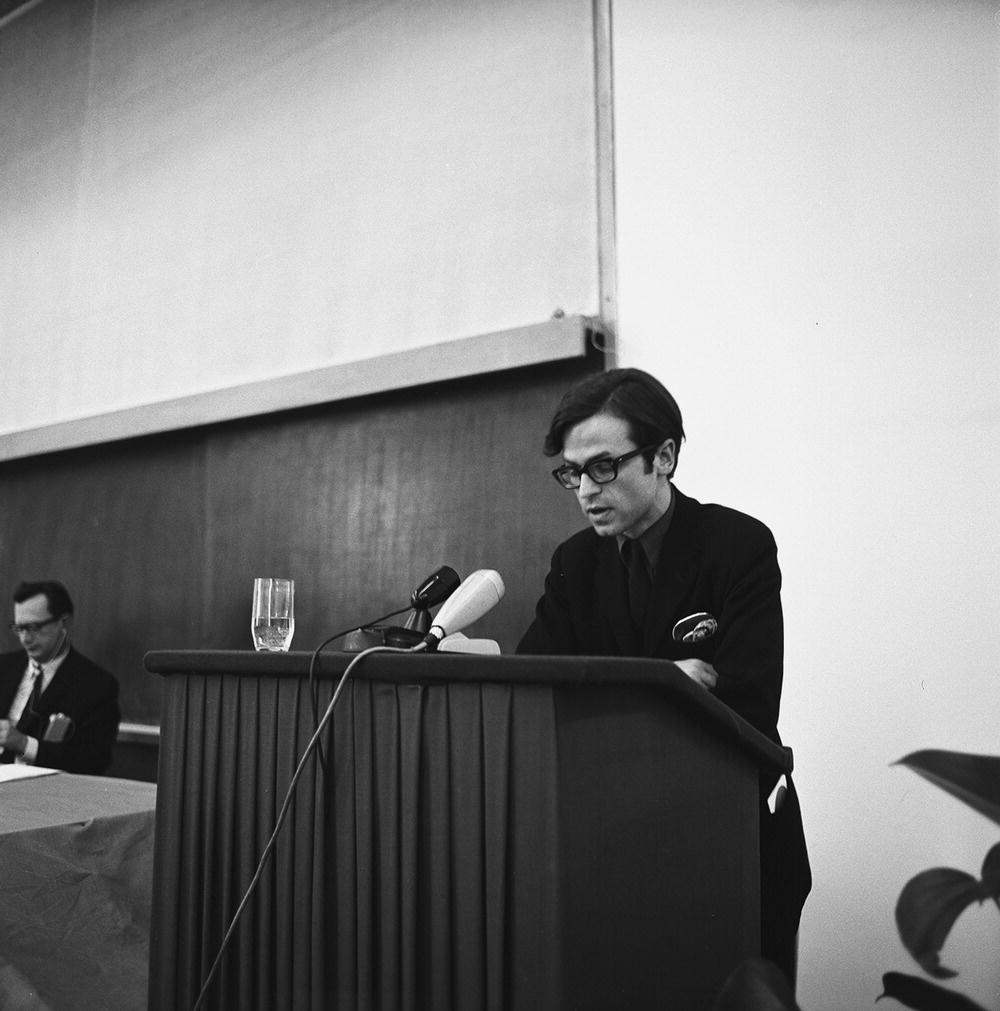

Figure 2.2 Jonathan Benthall from the Computer Arts Society, London, at the symposium at tendencies 4, “Computers and Visual Research,” RANS Moša Pijade, Zagreb, 1969.

The aforementioned symposium and exhibition in Zagreb were the concluding events of the ambitious tendencies 4 program that had begun in Zagreb a year earlier, in the summer of 1968, with an international colloquium and exhibition of computer-generated graphics also titled Computers and Visual Research. The formal criteria applied in the selection of “digital” works for the exhibition were rigorous; flowcharts and computer programs of digital works were requested, and the artworks by pioneer Herbert Franke, created by means of analog computing, were not included but were presented in a parallel 1969 exhibition titled nt 4—recent examples of visual research, which showed analog artworks of previous New Tendencies styles.

In connection with the tendencies 4 and tendencies 5 programs, nine issues of the bilingual magazine bit international were published from 1968 to 1972. The editors’ objective was “to present information theory, exact aesthetics, design, mass media, visual communication, and related subjects, and to be an instrument of international cooperation in a field that is becoming daily less divisible into strict compartments” (Bašičević and Picelj 1968). The magazine’s title bit, short for binary digit, refers to the basic unit of information storage and communication. The total number of editorial pages published in the nine issues of bit international and the related tendencies 4 and tendencies 5 exhibition catalogues was over 1400.

Between 1968 and 1973 [New] Tendencies in Zagreb functioned as an international network that once again bridged the Cold War blocs, but this time for a different group of people and organizations: more than 100 digital arts practitioners, among them Marc Adrian, Kurd Alsleben, Vladimir Bonačić, Charles Csuri, Waldemar Cordeiro, Alan Mark France, Herbert Franke, Grace Hertlein, Sture Johannesson, Hiroshi Kawano, Auro Lecci, Robert Mallary, Gustav Metzger, Leslie Mezei, Petar Milojević, Manfred Mohr, Jane Moon, Frieder Nake, Georg Ness, Michael Noll, Lilian Schwartz, Alan Sutcliffe, and Zdenek Sykora; art groups such as ars intermedia from Vienna, Grupo de Arte y Cybernética from Buenos Aires, and Compos 68 from the Netherlands; artists based at universities such as the Computation Center at Madrid University and the Groupe art et Informatique de Vincennes (GAIV), in Paris; science research centers, such as the Institute Ruđer Bošković from Zagreb; theoreticians such as Jonathan Benthall, Max Bense, Herbert Franke, Abraham Moles, and Jiří Valoch, among others; corporate research departments, such as Bell Labs, IBM, MBB Computer Graphics, CalComp, and networks such as the Computer Arts Society (CAS) from London.

In 1973 the curators of the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb opened up the [New] Tendencies to conceptual art, partly due to a proposal by Jonathan Benthall (Kelemen 1973).11 The last exhibition, tendencies 5, consisted of three parts: constructive visual research, computer visual research, and conceptual art. This combination made [New] Tendencies the unique example in art history that connected and presented those three forms and frameworks of art—concrete, computer, and conceptual—under the same roof.12 The audio recordings of the accompanying symposium’s proceedings—on the subject of “The Rational and the Irrational in Visual Research Today”—is evidence of a mutual disinterest and blindness among constructive and computer visual research, on the one hand, and conceptual art, on the other. In the computer visual research exhibition section of the tendencies 5 exhibition, a new generation of computer artists presented their works, among them the groups Groupe Art et Informatique de Vincennes (GAIV) from France, and Computation Center at Madrid University from Spain, as well as Centro de Arte y Comunicación from Argentina (CAYC).13 CAYC would later shift their initial focus on digital arts toward conceptual art practices, which became obvious in the 1971 exhibition Arte de sitemas14 in which both groups of computer and conceptual artists participated. The developments of constructing digital images were out of focus for most of the conceptual art of that time, as its interest relies on non-objective art. Nevertheless, NT organizers tried to bind those practices throughout the notion of the program. Radoslav Putar, director of the Gallery, used the term “data processing” to describe methods of conceptual art, though this possible link was not investigated further (Putar 1973). Frieder Nake (1973) identified a similarity between computer and conceptual art on the level of “separation of head and hand,” and discussed that separation as a production structure following the logic of capitalism.

The very process of mounting New Tendencies’ international exhibitions at different venues around Europe run by different organizers, as well as the ways of producing publications and gathering in formal and informal meetings, were marked by different types of communication and teamwork and the formation of different committees for particular programs. Due to its popularization and growing importance, New Tendencies passed through numerous disagreements between the organizers and different factions, particularly the participants in the first phase of New Tendencies before 1965, which considered itself as a movement. At specific moments, organizations from Milan, Paris, or Zagreb would lead the actions, while different international committees performed different tasks formed over time. The peak of complexity of the [New] Tendencies organization was reached during the tendencies 4 exhibition, which, following detailed preparations, was communicated through fourteen circular newsletters (PI—programme of information) written in Croatian, English, and French. The output, realized within a year (1968–1969), consisted of a juried competition, six exhibitions, two international symposia (both with multi-channel simultaneous translations into Croatian, English, French, German, and Italian), the initiation and publication of the initial three issues of the magazine bit international, and finally the exhibition catalogue tendencies 4. These activities demonstrate the energy surrounding digital arts in Zagreb and among the international partners and participants, as well as their agenda to contextualize the practice and theory of digital arts within mainstream contemporary art in the long run.

A spin-off or extension of the [New] Tendencies network of digital arts was active in Jerusalem from 1972 until 1977. The leading figure was Vladimir Bonačić, a scientist-turned-artist thanks to New Tendencies who created interactive computer-generated light objects in both gallery and public spaces. On the basis of an agreement between the Ruđer Bošković Institute from Zagreb and the Israel Academy of Sciences, the Jerusalem Program in Art and Science, a research and training program for postgraduate interdisciplinary studies in art and science, was founded, in 1973, at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, which Bonačić directed and where he taught computer-based art. For this program he established collaborations with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Israel Museum. In 1974 he organized an international Bat Sheva seminar, “The Interaction of Art and Science,” in which several [New] Tendencies protagonists participated, among them Jonathan Benthall, Herbert W. Franke, Frank Joseph Malina, Abraham Moles, A. Michael Noll, and John Whitney. In 1975, Willem Sandberg, a Dutch typographer and director of the Stedelijk Museum, received the Erasmus Prize in Amsterdam. On Sandberg’s recommendation, half of the prize was dedicated to the Jerusalem Program in Art and Science. Alongside computer-generated interactive audiovisual art objects, the projects created by Bonačić’s bcd cybernetic art team included the development of a new design for a computable traffic light system; the first functional digitalization of the Arabic alphabet was also realized within the academy program (Bonačić 1975). From 1978 to 1979 the bcd cybernetic art team realized a socially engaged project titled Palestine Homeland Denied in the form of thirty-five printed posters, which included the computer-generated alphabet and images of 385 destroyed Palestinian villages.

Computer-generated art’s attraction gradually faded from the artworld at large during the 1970s. Computer graphics of the 1970s explored possibilities for figurative visuals and—by delivering animations and special effects for the mainstream film industry—entered the commercial world as well as the military sector, advancing virtual reality techniques that simulated “real life.” This development—within the larger context of an increasing dominance of conceptual and non-objective art building on post-Duchampian ideas of art and representation—led to the almost-total exclusion of computer-generated art from the contemporary art scene around the mid-1970s. This process was further fueled by the rising anti-technological sentiment among the majority of a new generation of artists, created by the negative impact of the corporate-military-academic complex’s use of science and technology in the Vietnam War and elsewhere and expressed in the previously mentioned statement by Gustav Metzger in 1969, the protest movement by Japanese artists against Expo ’70, and similar events, such as the throwing of stones at a computer artist in Los Angeles15 a year later. The misuse of science and technology in the Vietnam War was described by Richard Barbrook:

M.I.T. modernization theory would prove its (USA) superiority over the Maoist peasant revolution. […] Since the information society was the next stage in human development, the convergence of media, telecommunications and computing must be able to provide the technological fix for anti-imperialist nationalism in Vietnam. During the late-1960s and early-1970s, the US military made strenuous efforts to construct an electronic barrier blocking the supply routes between the liberated north and the occupied south. Within minutes of enemy forces being detected by its ADSID sensors, IBM System/360 mainframes calculated their location and dispatched B-52 bombers to destroy them.

(Barbrook 2007, 177)

In the mid-1970s major protagonists in the field of digital art, such as Frieder Nake, Gustav Metzger, and Jack Burnham, shifted the tone of discourse on art, science, and technology. In Zagreb the [New] Tendencies movement experienced difficulties: tendencies 6 started with five-year-long ongoing preparations by a working group that could not find a consensus on how to contextualize and support “computers and visual research” and finally organized only an international conference titled tendencies 6—Art and Society in 1978, which again confronted very few computer artists with a majority of conceptual art practitioners. The planned tendencies 6 exhibition never took place. Instead, the New Art Practices exhibition—running in parallel with the last [New] Tendencies event, the “Art and Society” conference— presented the first regional (Yugoslav federation) institutional retrospective of conceptual art practices. While developing the exhibition concept for tendencies 6, the organizers from Zagreb actually sent more than 100 calls for works to video activists and community-engaged video collectives around the world, but there were no answers. The video activism of the 1970s also remains an under-researched phenomenon that is often skipped in the narratives of both media art and mainstream contemporary art history, yet provides contents that bridge the gap between socially engaged art and technologies.

Media-oriented conceptual artists of the 1970s started to use mostly analog media such as typewritten text, video, photography, and Xerox, and only a few used digital technologies. It took about twenty years until digital arts returned to the contemporary art scene in the (late) 1980s, but this time infused with the experiences of both social engagement and conceptual art practices. This return after a long disconnect would lead to the creation of many new digital arts networks. The boom of digital art networks since the 1990s has been propelled by the advances in Internet technologies and a cultural climate infused by the fast growth of new media and digital cultures that have gradually become interwoven with the everyday life of the majority of the world’s population in the 21st century. Some digital art networks disappeared quickly, but others are long-lasting and still growing; growth diagrams show that their curve almost catches up with that of the IT sector and creative industries.

Digital Art Networks of the 1980s

The 1970s saw the emergence of significant magazines on electronic and digital arts such as Radical Software (1970–1974) by the Raindance Collective and Computer Graphics and Art (1976–1978). The Leonardo journal (1968– ) is the only one of the early periodicals that is still published today; it expanded its organizational frame beyond a printed magazine and to the network at a later point, in the 1980s.

Leonardo is a peer-reviewed academic journal founded in 1968 “with the goal of becoming an international channel of communication for artists who use science and developing technologies in their work” (MIT 2013). It was established in Paris by artist and scientist Frank Malina. Roger Malina, who took over operations of the journal upon Frank Malina’s death in 1981, moved it to San Francisco. In 1982 the International Society for the Arts, Sciences and Technology (ISAST) was founded to further the goals of Leonardo by providing a venue of communication for artists working in contemporary media. The society also publishes the Leonardo Music Journal, the Leonardo Electronic Almanac, Leonardo Reviews, and the Leonardo Book Series. All publications are produced in collaboration with The MIT Press. Other activities of Leonardo include an awards program, as well as participation in annual conferences and symposia such as the Space and the Arts Workshop, and the annual College Art Association conference. Leonardo has a sister organization in France, the Association Leonardo, that publishes the Observatoire Leonardo des arts et des technosciences (OLATS) web site. While encouraging the innovative presentation of technology-based arts, the society also functions as an international meeting place for artists, educators, students, scientists, and others interested in the use of new media in contemporary artistic expression. A major goal of the organization is to create a record of personal and innovative technologies developed by artists, similar to the documentation of the findings of scientists in journal publications. Leonardo has helped to bridge the gap between art and science from the 1960s until today and has shown developments in art and science intersections as a continuum.

Since the late 1980s and in the 1990s, in particular, media arts have come into global focus again, and numerous institutions, magazines, media labs, university departments, online platforms, conferences, and festivals have emerged, not necessarily functioning as organized international networks, but providing a place for personal networking. Practices that were once subsumed under terms such as (new) media art, digital art, art and technology, art and science have become so diversified that no single term can work as a signpost any more. We may trace these developments within single platforms such as Leonardo, the longest lasting journal in the field as of today, and the longest lasting festival, Ars Electronica, launched in Linz, Austria, in 1979. Initially it was a biennial event, and has been held annually since 1986, with each festival focused on a specific theme. In its growth phase, two key factors drove the festival’s subsequent development: on the one hand, the goal to create a solid regional basis by producing large-scale open-air projects such as the annual multimedia musical event Klangwolke (Sound Cloud); and, on the other hand, to establish an international profile by collaborating with artists, scientists, and experts—for instance, by hosting the first Sky Art Conference held outside the USA. Since 1987 Ars Electronica organizes the Prix Ars Electronica, a yearly competition in several categories that have changed over time. In 1996 the Ars Electronica Center opened as a year-round platform for presentation and production that includes the Ars Electronica Futurelab, a media art lab originally conceived to produce infrastructure and content for the Center and Festival, but increasingly active in joint ventures with universities and private-sector research and development facilities. In 2009 the Center moved to a new building,

reoriented with respect to both content and presentation. In going about this, the principle of interaction was expanded into comprehensive participation. In designing exhibits and getting material across, the accent is placed on the shared presence of artistic and scientific pursuits. The substantive focus is on the life sciences.

(Ars Electronica 2013)

Media artist and theoretician Armin Medosch (2013), among others, has criticized Ars Electronica for a growing lack of criticality:

Ars Electronica only continues with a long tradition, by uncritically incorporating a positivistic view of science whilst riding the waves of hype about technological innovations. The point is, that this criticism isn’t new either. In 1998, when Ars Electronica chose the topic of “Infowar” media philosopher Frank Hartmann wrote: “Interestingly enough, the word ‘culture’ has hardly been heard at this conference, which in the end is part of a cultural festival. The social aspects of cyberwar have been excluded. It seems to me that one wanted to decorate oneself with a chic topic that reflects the Zeitgeist, while avoiding any real risk by putting the screen of the monitor as a shield between oneself and the real danger zones.” These are the words of the same Frank Hartmann who will speak at the Ars Electronica conference as one of the few non-natural scientists this year [2013]. Ars Electronica manages to discuss the Evolution of Memory in an utterly de-politicised manner, and that only months after Edward Snowden exposed the existence of the NSA’s gigantic surveillance program that exceeds anything that we have known before. […] The pseudo-scientific metaphors that Ars Electronica loves so much, usually taken from genetics and biology, and in recent times increasingly from neuro-science, lead to the naturalisation of social and cultural phenomena. Things that are historical, made by humans and therefore changeable, are assumed to be of biological or of other natural causes, thereby preventing to address the real social causes. In addition, such a manoeuvre legitimates the exercising of power. By saying something is scientific, as if “objective,” a scientific or technocratic solution is implied. The pseudo-scientification leads to the topic being removed from democratic discussion. […] Through the way how it has addressed information technologies since 1979 Ars Electronica has concealed their real consequences in a neoliberal information society. For this it has used again and again flowery metaphors which seemingly break down barriers between cultural and scientific domains in a pseudo-progressive way. According to Duckrey, Ars Electronica has in 1996, with their frequent references to a “natural order,” “reduced diversity, complexity, noise and resistance, blending out the cultural politics of memory in the age of Memetics.”

(Medosch 2013)

Facing the challenges of keeping the critical discourse up to date with the latest developments in the field(s) and the large quantity of presented artworks, as well as its own growth over several decades, Ars Electronica still plays an important role in the field of digital arts next to other large-scale festivals that have been organized over the decades, such as DEAF—Dutch Electronic Art Festival in Rotterdam (organized by V2 since 1987) or Transmediale in Berlin (since 1988). Such festivals offer possibilities for presenting and sometimes producing demanding and complex projects. As media (art) cultures are developing rapidly, such festivals have recently attracted wider audiences and necessarily entered the dangerous field of populism, with or without criticality. New kinds of spaces have been developed for personal meetings, work, and presentations, and new institutions with media or hack labs, festivals, temporary workshops, and camps have evolved. Different from the field of contemporary art, insights into context in the process-based new media field are often provided by presentations at conferences and festivals rather than through artworks presented in exhibitions or on online platforms. In the context of international networking, festivals and conferences have been and still are regular gathering places for practitioners.

Is It Possible to Organize a Meta-Network?

At the beginning of the 1990s electronic and digital arts networks rapidly emerged all over the world, and the idea of a meta-network was formed within this new wave of enthusiasm.

Founded in the Netherlands in 1990, ISEA International (formerly Inter-Society for the Electronic Arts) is an international non-profit organization fostering interdisciplinary academic discourse and exchange among culturally diverse organizations and individuals working with art, science, and technology. The main activity of ISEA International is the annual International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA) that held its 25th anniversary celebration in 2013, where one of the founders, Wim van der Plas, reflected on its history and goals:

The first ISEA Symposium was not organised with the goal to make it a series, but with the aim to establish the meta-organisation. The symposium, held in 1988 in Utrecht, The Netherlands, was the reason for creating a gathering where the plan for this association of organisations could be discussed and endorsed. This is exactly what happened and the association, called Inter-Society for the Electronic Arts (ISEA) was founded 2 years later in the city of Groningen (The Netherlands), prior to the Second ISEA symposium, in the same city. The continuation of the symposia, thus making it a series, was another result of the historic meeting in Utrecht. Quite possibly the goal was too ambitious and the founding fathers too much ahead of their times. When a panel meeting was organized on the stage of the second symposium, with representatives of SIGGRAPH, the Computer Music Association, Ars Electronica, ISAST/Leonardo, ANAT, Languages of Design and others, there was quite a civilized discussion on stage, but behind the curtains tempers flared because nobody wanted to lose autonomy.

[…] It was an association and it’s members were supposed to be institutes and organisations. However, because we had no funding whatsoever, we decided individuals could become members too. We managed to get about 100, later 200 members, many of them non-paying. Only a few [5–10] of the members were institutions. […] Over the years, more than 100 newsletters have been produced. The newsletter had an extensive event agenda, job opportunities, calls for participation, etc. […] Our main job was to coordinate the continued occurrence of the symposia. […]

(van der Plas 2013)

A main goal of the 1999 ISEA International “General Assembly on New Media Art,” called Cartographies, was to make progress “toward a definition of new media art” (van der Plas 2013). Present were representatives of the Inter-Society, the Montreal Festival of New Cinema & New Media, Banff, the University of Quebec, McGill University, the Daniel Langlois Foundation (all Canadian organizations), Ars Electronica (Austria), V2 (Netherlands), Art3000 (France), Muu (Finland), Mecad (Spain), DA2 (UK), Walker Art Center (USA), and others. Valérie Lamontagne summarized the conversation by stating that “Certain initiatives did result from this discussion, mainly the desire to form a nation-wide media arts lobbying organization” (Lamontagne 1999).

Since 2008 the University of Brighton has hosted the headquarters of ISEA International, which has moved from an association to a foundation as organizational structure. Van der Plas commented: “The ISEA INTERNATIONAL foundation, contrary to the Inter-Society, has limited its goals to what it is able to reasonably accomplish. The Inter-Society had been too optimistic and too naïve. A volunteer organisation requires professionals to make it work effectively” (van der Plas 2013).

The ISEA symposia still take place annually in cities around the world and have grown to such an extent that the 19th edition in Sydney (2013) featured five parallel sessions over three days, accompanied by exhibitions, performances, public talks, workshops, and other events. Roger Malina, who coined the Inter-Society’s name, commented on the problems the organization is facing today: “It is not at all clear to me what the right networking model is to use for an Inter-Society. Clearly we don’t want a 19th or 20th century model of ‘federation’” (Malina 2013).

With the advent of the World Wide Web in the mid-1990s, new kinds of local, regional, and international networks on different topics were created, mostly organized as specialized Internet mailing lists (moderated or not), free of membership fees and supporting openness in all respects, among them the Thing, Nettime, Rhizome, and Syndicate mailing lists/networks of the 1990s, to name just a few. The English language became a new standard for international communication, and other languages determined the local or regional character of the online network. Some networks were more focused on practice while others concentrated on developing social and theoretical discourse, but most of them merged theory and practice. A new element in networking practice was that many of the participants in the same network would not meet in person. New strategies for face-to-face meetings were developed, such as those hosted by institutions, festivals, and conferences in the field.

Conclusion

The practices of networks such as [New] Tendencies, E.A.T., and the Computer Arts Society supported art that made use of machinic processes of communication and information exchange, and bridged both society’s and art’s transition from the industrial age to the information society. Their practices reinforced a creative use of digital technologies for actively participating in social contexts. These networks promoted an interdisciplinary approach and led the evolution of digital culture from cybernetics to digital art. They provided a context for digital arts within contemporary art, among other fields, and illustrated how a network of digital arts operated even before the time of Internet. The rapid expansion of institutions and networks of digital arts and cultures since the 1990s has gone hand in hand with negative social trends brought about or controlled through technologies, reminding us of the everlasting necessity of taking a critical stance toward social responsibilities. It is fascinating to see how history repeats itself both in terms of mistakes and advances, and there is much to learn from only half a century of digital arts and its many layers and interpretations.

References

- Argan, Giulio Carlo. 1965. “umjetnosti kao istraživanje” [art as research]. In nova tendencija 3, exhibition catalogue. Zagreb: Galerije grada Zagreba.

- Ars Electronica. 2013. “About Ars Electronica.” http://www.aec.at/about/en/geschichte/ (accessed December 5, 2014).

- Bašičević, Dimitrije, and Ivan Picelj, eds. 1968. “Zašto izlazi ‘bit’” [Why “bit” Appears]. In bit international 1: 3–5. Zagreb: Galerije grada Zagreba.

- Barbrook, Richard. 2007. Imaginary Futures. London: Pluto Press.

- Bonačić, Vladimir. 1975. “On the Boundary between Science and Art.” Impact of Science on Society 25(1): 90–94.

- Collins Goodyear, Anne. 2008. “From Technophilia to Technophobia: The Impact of the Vietnam War on the Reception of ‘Art and Technology.’” Leonardo 41(2): 169–173.

- Cordeiro, Waldemar. 1973. “Analogical and/or Digital Art.” Paper presented at The Rational and Irrational in Visual Research Today/Match of Ideas, Symposium t5, June 2, 1973, Zagreb. Abstract published in the symposium reader. Zagreb: Gallery of Contemporary Art.

- Eco, Umberto. 1962. “Arte cinetica arte programmata. Opere moltiplicate opera aperte.” Milan: Olivetti.

- Hyde, Gordon, Jonathan Benthall, and Gustav Metzger. 1969. “Zagreb Manifesto.” bit international 7, June, edited by Božo Bek: 4. Zagreb and London: Galerije grada/ Studio International. Audio recordings, Museum of Contemporary Art archives, Zagreb.

- IEEE. 2013. “IEEE—History of IEEEE.” http://www.ieee.org/about/ieee_history.html (accessed December 5, 2014).

- Kelemen, Boris. 1973. Untitled. In tendencije 5, exhibition catalogue. Zagreb: Galerija suvremene umjetnosti.

- Klüver, Billy, and Robert Rauschenberg. 1966. “The Mission.” E.A.T. Experiments in Arts and Technology, October 10.

- Klüver, Billy, and Robert Rauschenberg. 1967. E.A.T. News 1(2). New York: Experiments in Arts and Technology Inc.

- Kusahara, Machiko. 2007/2008. “A Turning Point in Japanese Avant-garde Art: 1964–1970.” Paper presented at re:place 2007, Second International Conference on the Histories of Media, Art, Science and Technology, Berlin, November. In Place Studies in Art, Media, Science and Technology—Historical Investigations on the Sites and the Migration of Knowledge, edited by Andreas Broeckman and Gunalan Nadarajan. Weimar: VDG, 2008.

- Lamontagne, Valérie. 1999. “CARTOGRAPHIES—The General Assembly on New Media Art.” CIAC. http://magazine.ciac.ca/archives/no_9/en/compterendu02.html (accessed December 5, 2014).

- Malina, Roger. 2013. “We don’t want a federation.” Presented at The Inter-Society for the Electronic Arts Revived?, panel at ISEA 2013, Sydney, June 7–16. http://www.isea2013.org/events/the-inter-society-for-the-electronic-arts-revived-panel/(accessed June 21, 2013).

- Mason, Catherine. 2008. A Computer in the Art Room: the Origins of British Computer Arts 1950–80. Hindringham, UK: JJG Publishing.

- Medosch, Armin. 2013. “From Total Recall to Digital Dementia—Ars Electronica 2013.” The Next Layer. http://www.thenextlayer.org/node/1472 (accessed September 6, 2014).

- Meštrović, Matko. 1963. Untitled. In New Tendencies 2, exhibition catalogue. Zagreb: Galerije grada Zagreba.

- Metzger, Gustav. 1969. “Automata in history.” Studio International 178: 107–109.

- Metzger, Gustav. 1970. “Five Screens with Computer.” In tendencije 4: computers and visual research, exhibition catalogue. Zagreb: Galerija Suvremene Umjetnosti.

- MIT. 2013. “MIT Press Journals—About Leonardo.” http://www.mitpressjournals.org/page/about/leon (accessed August 1, 2014).

- Moles, Abraham. 1965. “Kibernetika i umjetničko djelo.” In nova tendencija 3, exhibition catalogue. Zagreb: Galerije grada Zagreba.

- Nake, Frieder. 1973. “The Separation of Hand and Head in “Computer Art”. In The Rational and Irrational in Visual Research Today/Match of ideas, symposium t–5, 2 June 1973, symposium reader, Gallery of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, n.p.

- PAGE. 1971. No. 16, 7. London: Computer Arts Society.

- van der Plas, Wim. 2013. “The Inter-Society for the Electronic Arts Revived?.” Introduction to panel session at ISEA 2013, Sydney, June 7–16. http://www.isea2013.org/events/the-inter-society-for-the-electronic-arts-revived-panel/ (accessed December 5, 2014).

- Popper, Frank. 1965. “Kinetička umjetnosti i naša okolina.” In nova tendencija 3, exhibition catalogue. Zagreb: Galerije grada Zagreba.

- Putar, Radoslav, 1973. Untitled. In tendencije 5, exhibition catlogue. Zagreb: Galerija suvremene umjetnosti.

- Rosen, Margit, Darko Fritz, Marija Gattin, and Peter Weibel, eds. 2011. A Little-Known Story about a Movement, a Magazine, and the Computer’s Arrival in Art: New Tendencies and Bit International, 1961–1973. Karlsruhe and Cambridge, MA: ZKM/The MIT Press.

- Sutcliffe, Alan. 2003. Interview with Catherine Mason, January 17. CAS. http://computer-arts-society.com/history (accessed January 15, 2015).

- van Tijen, Tjebbe. 2011. “Art Action Academia, Research Center Art Technology and Society.” http://imaginarymuseum.org/imp_archive/AAA/index.html (accessed December 5, 2014).

- van Tijen, Tjebbe. 2011. “Art Action Academia, Manifesto against World Expo in Osaka.” http://imaginarymuseum.org/imp_archive/AAA/index.html (accessed December 5, 2014).

- van Tijen, Tjebbe, and Nic Tummers. 1968. “Manifesto against World Expo in Osaka.” Distributors FRA Paris, Robho revue and GBR London, Artist Placement Group (APG). http://imaginarymuseum-archive.org/AAA/index.html#A14 (accessed August 1, 2012).

- Vasulka, Woody. 1998. “Experiments in Art and Technology. A Brief History and Summary of Major Projects 1966–1998.” http://www.vasulka.org/archive/Writings/EAT.pdf (accessed December 5, 2015).

- Wolk, Johannes van der, ed. 1970. “# 30.” De werkgroep voor computers en woord, beeld en geluid. Newsletter no. 5, May 15, Utrecht: 2.

- Wolk, Johannes van der, ed. 1971. “# 105.” De werkgroep voor computers en woord, beeld en geluid. Newsletter no. 9, June 30, Utrecht: 3–5.

Further Reading

- Brown, Paul, Charlie Gere, Nicholas Lambert, and Catherine Mason, eds. 2008. White Heat Cold Logic: British Computer Art 1960–1980. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, Leonardo Book Series.

- Denegri, Jerko. 2000/2004 (English translation). Umjetnost konstruktivnog pristupa. The Constructive Approach to Art: Exat 51 and New Tendencies. Zagreb: Horetzky.

- Fritz, Darko. 2006. “Vladimir Bonačić – Early Works.” Zagreb: UHA ČIP 07–08, 50–55.

- Fritz, Darko. 2007. “La notion de «programme» dans l’art des années 1960 – art concret, art par ordinateur et art conceptuel” [“Notions of the Program in 1960s Art – Concrete, Computer-generated and Conceptual Art”]. In Art++, edited by David-Olivier Lartigaud. Orléans: Editions HYX (Architecture-Art contemporain-Cultures numériques), 26–39.

- Fritz, Darko. 2008. “New Tendencies.” Zagreb: Arhitekst Oris 54, 176–191.

- Fritz, Darko. 2011. “Mapping the Beginning of Computer-generated Art in the Netherlands.” Initial release, http://darkofritz.net/text/DARKO_FRITZ_NL_COMP_ART_n.pdf (accessed December 5, 2014).

- Meštrović, Matko. “The Ideology of New Tendencies.” Od pojedinačnog općem (From the Particular to the General). Zagreb: Mladost (1967), DAF (2005).

- Rose, Barbara. 1972. “Art as Experience, Environment, Process.” In Pavilion, edited by Billy Klüver, Julie Martin, and Barbara Rose, 93. New York: E.P. Dutton.