4

Proto-Media Art: Revisiting Japanese Postwar Avant-garde Art

Machiko Kusahara

The history of Japanese media art goes back to the postwar avant-garde art of the 1950s and 1960s, both in terms of attitudes toward media technology and the artists themselves, who later played crucial roles in launching institutions for media art including educational programs and art centers. Soon after World War II, a sense of freedom brought an explosive energy to visual art. New forms of art emerged within a few years after the war, when major cities were still making an effort to recover from the ashes. With the recovery of freedom of speech and expression, innumerable cultural activities took place all over the country and many art groups were formed. Theoretical leaders such as Shuzo Takiguchi, Jiro Yoshihara, and Taro Okamoto led the art scene and inspired young artists to carry out highly experimental activities in the early 1950s—activities original and powerful even by today’s standards.

Among the many groups that were active from 1950 to 1970, Jikken Kobo and the Gutai Art Association are of particular interest when seen from the point of view of today’s media art. As the country started to rebuild international relationships, Japanese artists became involved in art movements such as art informal, abstract expressionism, Neo-Dada and Fluxus.1 The aim of this chapter is to provide not an in-depth introduction to their works and projects but a snapshot of what was happening in art in connection with the social and political background of the era. For this purpose, prewar art history will be briefly introduced. It would require another essay to analyze the complex and extremely rich activities in the 1960s that connected art, design, film, theatre, and music, among many other fields. The role that the 1970 Universal Exposition in Osaka (Osaka Expo ’70) played in the death of avant-garde art and the birth of media art is yet another topic that would warrant an essay of its own.

An Overview of Postwar Avant-garde Art

The Japanese postwar avant-garde art movement was short-lived but extremely active and colorful in spite of the country’s difficult situation. Recent publications in English that accompanied major exhibitions provide rich source material for understanding the phenomenon. For example, Gutai: Splendid Playground (February–May 2013) at the Guggenheim Museum in New York offered a rare opportunity to view the group’s unique activities from its earliest stages to its final days. The exhibition titled Art, Anti-Art, Non-Art: Experimentations in the Public Sphere in Postwar Japan, 1950–1970, shown at the Getty Research Institute in 2007, gave an excellent overview of the wide spectrum of artistic activities based on research. Tokyo 1955–1970: A New Avant-Garde (November 2012–February 2013) at New York’s MoMA (Museum of Modern Art) focused on art activities and groups in Tokyo including Neo Dadaist Organizers (Neo-Dada), Hi Red Center, and Fluxus, highlighting the multidisciplinary approaches and practices that characterized the avant-garde art in Tokyo during that time.

In Japan, curatorial efforts exploring what the postwar avant-garde art movement meant for society gained visibility after the Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. In December 2012 the exhibition Quest for Dystopia at the Metropolitan Museum of Photography in Tokyo included a section titled “Protest and Dialogue – Avant-garde and Documentary,” which focused on documentary films and videos produced by avant-garde artists in the 1960s and 1970s. During the same season a large-scale exhibition titled Jikkenjo 1950s (“testing ground 1950s”) was held at the National Museum of Modern Art as the second part of its 60th anniversary special exhibition. The chief curator, Katsuo Suzuki, states in the accompanying anthology of texts (in Japanese only) that the 1950s were an era when people could imagine and realize many possibilities, and multiple options were still open for Japan’s future. According to Suzuki, groups, movements, debates, and publications developed by art critics, artists, and other cultural figures were the practice to create “public spheres” that would support democracy, art, and the power of cultural resistance. With the period of rapid economic growth from 1955 to1973, such activities gradually diminished.

Prewar Avant-garde Art

Japanese art has a long history, but it is very different from its counterpart in the West. Western-style painting was officially introduced only in the second half of the 19th century. As a result, Japanese and Western paintings remained two separate categories, dominated by two different groups of established artists. These artists ran the official Imperial Academy of Fine Arts Exhibition (Teiten), which was held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Ueno Park.2 Artists frustrated by the hierarchical art communities and their favoritism founded their own groups and curated exhibitions. As an action against Teiten they launched the Nika-kai (meaning “second section group”) annual exhibition in 1914 to exhibit their works.

By the 1920s, modernist culture flourished in major cities, especially in Tokyo. Cinemas, variety theatres, and dance halls clustered on the streets of Asakusa. Jazz, French chanson, and European classic music became popular on the gramophone and radio. Less than half a century after Japan opened its borders, Western culture was knit into urban life.3 New trends in art, design, and theatre, among them Bauhaus, constructivism and futurism, arrived almost in real time. The Dadaist movement was introduced in 1920 and had a strong impact especially on poets. Their first Dada magazine came out as early as in 1922.

Surrealism was introduced in the late 1920s and had an immediate influence among poets, theorists, and artists, mostly as a new style of expression rather than social criticism or a political attitude. The two leading figures were painter Ichiro Fukuzawa and Shuzo Takiguchi, a poet and theorist who translated Andre Breton’s Surrealism and Painting in 1930.4 Surrealists showed their works in the “9th Room” of the Nika-kai exhibition, which served as a core part of prewar avant-garde art. Meanwhile, Proletarian artists influenced by the Russian Revolution gathered and formed San-ka (the 3rd section group).

The age of modernism did not last long. While people still enjoyed jazz and dance, and enthusiastically welcomed Charlie Chaplin’s visit, militarism spread quickly. Soon democracy movements were demolished, and artists who were suspected of having socialist tendencies were harshly oppressed. Fukuzawa and Takiguchi were arrested and detained for months in 1934 on the groundless allegation that they were part of the international surrealist movement connected to communism. This marked the end of the prewar avant-garde art movement. Taro Okamoto, who had lived in Paris and achieved recognition among surrealists and abstract painters, was forced to come back to Japan in 1940. After his first solo exhibition in Tokyo he was drafted and sent to the Chinese front. Major painters—of both the Japanese and Western school—were involved in war painting, but surrealist or abstract paintings were of no use for propaganda.5

Postwar Political Situation and the Art Community: 1945–1960

When the war ended in 1945 and the occupation forces arrived with overwhelming material presence, it became clear that the wartime spiritualism could not resist the power of science and technology. The belief that Japan had to remodel itself as an industrial nation was widely shared. Osamu Tezuka’s manga and animation Mighty Atom (1951, titled Astro Boy outside of Japan) represents this vision. In 1970, this ideal of industrialization was visualized in the world exposition in Osaka, for which many of the avant-garde artists were hired.6

Establishing democracy and eliminating any remaining traces of wartime nationalism was the most urgent goal for GHQ, the occupation force operated by the United States.7 Although there were no official convictions of former art leaders who had promoted the war propaganda, they were publicly criticized by those who had remained “innocent.”8 The discussion inevitably led to heated arguments about the nature of art and the responsibilities of artists. Following the collapse of the prewar and wartime hierarchy, numerous groups of artists and theorists formed, actively working and collaborating in a spirit of excitement about the new possibilities that had opened up for them. The group that played the most important role in the formation of the avant-garde art movement was Yoru no Kai (The Night Society, named after Taro Okamoto’s painting), founded in 1948 by Okamoto and Kiyoteru Hanada, a literary critic who most actively argued for the democratization of art. For the younger generation who had had no chance of receiving a proper art education during the war, Okamoto’s texts on art history and theory—testament to the fact that he had inherited his mother’s passion for writing as well as his father’s talent in art—must have been a liberation.9 Young artists joined the group’s meetings to learn about art history and theory, and to discuss future Japanese art.

Art classes were also held. The Avant-Garde Artists’ Club, which was founded in 1947 by artists and critics including Takiguchi with the aim of democratizing the art community, opened its Summer Modern Art Seminar in July 1948. Leading art critics and painters, including Takiguchi and Okamoto, taught the class. As a theorist and art critic with a firm theoretical background who had not yielded to wartime militarism, Takiguchi soon became a leading figure in the postwar art scene. He helped launching not only the annual Yomiuri Indépendant (which will be further discussed in the next section) but also Takemiya Art Gallery in the central part of Tokyo, an independent art space for exhibitions of young artists he discovered. Securing such a venue was an important step at a time when art museums were still scarce and there was no regular space for contemporary art.

As Okamoto’s works show, Western art in Japan had been under European (especially French) influence before the war. The postwar occupation brought a major change. Cultural programming was an important part of the GHQ’s democratization policy. In November 1945, the library of the Civil Information and Educational Section (CIE), located in the center of Tokyo, opened its doors to the Japanese public with publications that introduced American culture and society, including a rich selection of art books and musical records.10 Books introducing the latest art movements were among them. As the United States had become the center of new movements in visual art, music, and dance from the beginning of World War II, the CIE library provided up-to-date information that was not available elsewhere. After years of an absence of any cultural atmosphere—high school students worked in factories while university students were drafted—people were hungry for books, art, music, or any other cultural activities. A law student named Katsuhiro Yamaguchi immediately visited the library when he saw a notice in the newspaper. Yamaguchi, who would soon become a central figure of Jikken Kobo, recalled that he decided to become an artist when he encountered works by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy at the library. Frequent visitors to the library included people who later would become major members of Jikken Kobo, such as Kuniharu Akiyama, Shozo Kitadai, Toru Takemitsu, Hideko and Kazuo Fukushima, and Takiguchi.11 Akiyama, who was a university student in French literature but extremely knowledgeable in music history, eventually took a role as an assistant organizing record concerts at CIE.12

The thirst for cultural activities was shared by a wider public. Rejoicing in the freedom of speech and expression, many circles focusing on art, music, theatre, etc. were formed among the people, especially students and workers, supported by the GHQ’s policy to help labor unions to grow. One of these art organizations, founded by a group of prewar as well as younger proletarian artists, launched the annual Nihon Indépendant art exhibition as early as 1947.13 The Communist Party actively promoted “cultural movements,” supported by the respect they had gained for their suffering during wartime and the international high tide of communism. However, the wind changed quickly as tension in East Asia increased. The People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, and the Korean War started in 1950. Communism spreading in Asia became a major concern for the United States. Instead of a promotion of democracy and freedom of speech, a Red Purge—the equivalent of McCarthyism in the United States—was conducted under the GHQ’s instructions around 1950. It is estimated that 30,000 people lost their jobs.14 In the process of redefining Japan as a “protective wall against Communism” (New York Times 1948), the occupation, except for that of Okinawa, ended in 1952.15 The 1950s therefore was the decade of politics. The immediate confusion after the war was settled, but the Cold War followed.

The Korean War (1952–1955) helped the Japanese economy to recover as Japan became the major supplier of commodities for the US forces in Asia, but people were also afraid of being involved in warfare again. The 1954 tragedy of the Lucky Dragon No. 5 tuna fishing boat in the South Pacific reminded them of their fear of nuclear weapons.16 The 1955 protest against US military bases, led by farmers who lost their land in Tachikawa, a western suburb of Tokyo, attracted much attention. In 1956 the government declared the postwar period to be over, based on the country’s rapid economic growth. But severe struggles between labor unions and enterprises continued.17 Moreover, the government’s decision to make Japan a cornerstone in America’s global strategy was not fully supported by everyone. Massive protests against signing the US–Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security (in Japanese abbreviated as Anpo) took place in 1960. When the treaty was signed in spite of a student’s death in one of the final demonstrations, a feeling of defeat was shared by many, including artists. The explosive energy that drove postwar Japan came to a halt.

Collectives, Exhibitions, and Organizations

Yomiuri Indépendant (1949–1963)

Yomiuri Indépendant (written “andepandan” in Japanese characters), the annual art exhibition that started in 1949—only four years after the war—played a crucial role in the birth of postwar avant-garde art.18 The annual non-juried exhibition chose the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum in Ueno—where the national Teiten was held in the prewar era—as its venue, and anyone could show their work by paying the fee. The exhibition was sponsored by Yomiuri newspaper and supervised by Shuzo Takiguchi.19 Yomiuri journalist Hideo Kaido, who was responsible for its cultural section, detested the prewar and wartime hierarchy in art. While the majority of the submitted works were said to be rather conventional paintings and sculptures including those by hobbyists, Yomiuri Indépendant, informally referred to as Yomiuri Anpan, offered an ideal space for independent artists and the most experimental works. Along with younger artists such as Shozo Kitadai and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, the Gutai founder Jiro Yoshihara was among its early participants.

“Anpan” is the name of a popular Japanese pastry. The reason why young artists such as Genpei Akasegawa preferred calling the exhibition “anpan” with a friendly tone rather than using the more art-ish French “Indépendant,” was probably more than a matter of mere abbreviation. “Anpan” was invented in the early Meiji era when bread was not yet part of Japanese daily culinary life. Instead of filling a small piece of bread (“pan” in Japanese, based on the original sound of the word introduced by the Portuguese in the 16th century) with apple preserve or chocolate, as in the case of French pastries, the bakers Kimura, father and son, used traditional bean paste (“an”) that was (and still is) familiar to most Japanese. In other words, they replaced the traditional flour- or rice-based exterior part—which is called “skin”—of Japanese cakes with the more substantial volume of the most basic Western food, which was new to most Japanese. Anpan was a huge success and the bakery was immediately commissioned to serve the emperor’s court, which made their reputation solid.20 It is believed that the invention of anpan made a substantial contribution to bringing bread onto Japanese tables. This well-known anecdote illustrates a typical way in which Western culture was introduced to and merged into Japanese culture. The abbreviation “Yomiuri anpan” was thus metaphorical, and it may explain the way young artists outside the traditional hierarchy of the art world felt closer to the exhibition.

From approximately 1959 onwards, performances and unusual, large-scale installations by art groups started to appear at Yomiuri Anpan. The most radical of all was Neo-Dada Organizers, the “anti-art” artists group that was formed in 1960 by Masanobu Yoshimura, Jiro Takamatsu, Natsuyuki Nakanishi, Shusaku Arakawa, Genpei Akasegawa, and Ushio Shinohara, among others.21 They performed “happenings” around the same time as, but independently from, Allan Kaprow, and introduced interactivity into their works.22 For the 1963 Yomiuri Indépendant exhibition—which would be the last one—Takamatsu exhibited a piece consisting of a string that extended outside the museum, crossing the streets and reaching the Ueno Station. Nakanishi submitted a work titled Clothpins Assert Churning Action, a performance in which he walked through the streets with his head and face covered by numerous cloth pins. Akasegawa exhibited a huge copy of a 1000 yen bank note, which was part of a series that later became part of a famous court case as a counterfeit note.23 Another project realized by Akasegawa, Nakanishi, Takamatsu, and Yasunao Tone was a “miniature restaurant” for which they sold tickets for dishes to visitors. Those who had expected a full meal were disappointed when they found out that the food was served in tiny sizes on a dollhouse dish. Body-centered performances also took place, including one performed nude. Takehisa Kosugi, who was a member of Group Ongaku (Group Music), sealed himself in a bag with a fastener and crawled around.

Yomiuri Indépendant ended in 1963—or, more precisely, the 1964 exhibition was canceled just before the opening, and that was the end of it. The conflict between the institutional framework of a public museum and the radical artists became visible in the 1962 exhibition with its destructive, noisy, or stinking junk art that went beyond the limits of what the organizers could support.24

Competition among avant-garde artist groups had already led to demonstrations of most unusual pieces of anti-art and non-art for several years (Merewether and Iezumi-Hiro 2007). Kyushu-ha (Kyushu School) were notorious for their anti-art approach as demonstrated by their infamous piece Straw Mat – Straw Mat, which was a straw mat from the floor of their studio rolled up and filled with garbage.25 The museum had stated rules forbidding types of works that produced extremely unpleasant sounds, or involved knives and materials that would stink or decay, but not all artists respected them. The cancellation of Yomiuri Indépendant did not stop the avant-garde art movements. The Neo-Dada artists Takamatsu, Akasegawa, and Nakanishi formed a new group, Hi Red Center, in the same year.26 The last and best-known project by the short-lived but brilliant group was the Be Clean performance (Let’s Participate in the HRC Campaign to Promote Cleanup and Orderliness of the Metropolitan Area!) in October 1964. Artists wearing white robes cleaned the sidewalks of Ginza in central Tokyo. It was an ironic commentary on the government’s campaigns to “clean up” Tokyo for the Olympic Games.27

One might argue that Yomiuri Indépendant illustrated the limits of a public museum and private media company. At the same time artists enjoyed freedom because they didn’t have to take on certain responsibilities thanks to the sponsor who took care of the exhibition management. Yomiuri Indépendant created opportunities for them to regularly present their works and to meet other artists and form a loose but important network among them. Another outcome was the rise of a critical discourse among artists and critics triggered by the conflicts created by the exhibition.

Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop, 1951–1957)

Jikken Kobo—Experimental Workshop being the official English name—was active from 1951 to 1957 in Tokyo.28 Without doubt, Jikken Kobo was the most experimental and technologically advanced group of artists in 1950s Japan. The group was ahead of its time and laid the basis for media art to come. A departure from the traditional art system clearly was a concept driving the group. Unlike many other artist groups, Jikken Kobo never announced the beginning or ending of the group, its policy, or the membership. Besides the group's shows, which were titled “presentations” instead of “exhibitions,” their activities included multimedia performances, workshops, concerts, photographic works for magazines and so on.29 Jikken Kobo’s members worked both in visual art and in music. Most of them came from outside of the academic art or music environment and were not bound to mainstream art. At the same time they were well informed about prewar and postwar art movements in the West, and freely appropriated elements from them. They gathered at members’ houses, inspiring each other and working together. Openness was a shared attitude. They extensively collaborated with others, widening their field of activities.

Jikken Kobo started as a voluntary gathering of visual artists and composers around Shuzo Takiguchi, who named the group when they were commissioned to realize, in collaboration with dancers, a multimedia ballet titled Picasso, La joie de vivre (Joy of Life), as part of a “Picasso Festival” accompanying an exhibition of Picasso’s paintings in 1951.30 The choice of ballet as a form of collaboration was an homage to the history of avant-garde art, referring to Dada’s and surrealists’ experimental ballets created by artists such as Francis Picabia, Erik Satie, and others in the 1920s; to Jean Cocteau and Diaghilev; and to the American avant-garde scene represented by John Cage and Merce Cunningham. Set designs required a wide variety of methods, tools, industrial materials, and scalability. The experience created a foundation for the group’s extensive activities. Many of them became leading figures in visual art and music as, for example, Toru Takemitsu who contributed not only to the international contemporary music scene but also to Japanese cinema by composing for many films including those by Akira Kurosawa and Nagisa Oshima.31 Although there is not enough space to fully introduce the group’s extremely rich body of works, reviewing its process of formation by taking a look at the paths of Shozo Kitadai and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi will give an idea of the group’s nature, the speed of its development, and the postwar environment.

Shozo Kitadai was a few years older than the other members and played a leading role in the group. He was born in 1921 in Tokyo, grew up amidst 1920s and early 1930s modernism and, influenced by his father, familiarized himself with photography at a young age. He studied metal engineering before being drafted in 1942 and sent to the South Pacific as an officer of telecommunications technology. He was detained after the war—as was Okamoto—and returned to Japan in 1947. After coming back to Tokyo he joined the aforementioned Summer Modern Art Seminar in July 1948. In August, Kitadai proposed to Yamaguchi, Hideko Fukushima, and a few other young artists he met at the seminar to form a group. Soon after, Fukushima’s young brother Kazuo, a composer, joined with his friends. The young artists and composers regularly met at Kitadai’s and Fukushima’s houses, discussing topics ranging from art history and contemporary art, to nuclear physics, relativity theory, and science fiction (Jikken Kōbō 2013, 49–51). Within a few months (November 1948) they had put together their first group exhibition including abstract paintings and a “mobile” by Kitadai, who was inspired by a picture of Alexander Calder’s work that he had encountered in a magazine. Kinetic sculpture would become an important element for Kitadai and Jikken Kobo, enabling remarkable stage design for dance performances.32

The exhibition generated a review by Okamoto, strongly supporting the group and their exhibition, in Bijutsu Techo, a magazine that played (and continues to play) a leading role in contemporary art. Imagine Kitadai’s excitement when he, the self-taught artist who had recently returned from detention, was highly appreciated by the leading artist/theorist of the era!33 In 1949, an abstract painting and a mobile that Kitadai had submitted to the first Yomiuri Indépendant generated praise in a review written by Takiguchi for Yomiuri newspaper. As an emerging artist, Kitadai was invited to be the stage designer for a performance by a contemporary ballet company in 1950.34 He created a sculptural composition, which was a novelty. Takiguchi once again highly praised him in Yomiuri, referring to Isamu Noguchi’s stage design for the Martha Graham Dance Company, and hoped this would be the first step in further collaborations between contemporary art and ballet. The following year Kitadai was invited again and designed an even more innovative set. The lighting designer for both performances was Naotsugu Imai, whom Kitadai had already known through a major circle of artists and poets.35 Imai would later become an important member of Jikken Kobo. What made Jikken Kobo so unique was the collaboration among multidisciplinary talents. Recognizing the potential of the group, Takiguchi commissioned them for the stage, costume, and musical design of Picasso, La joie de vivre in 1951, which marked the beginning of the group’s activity.

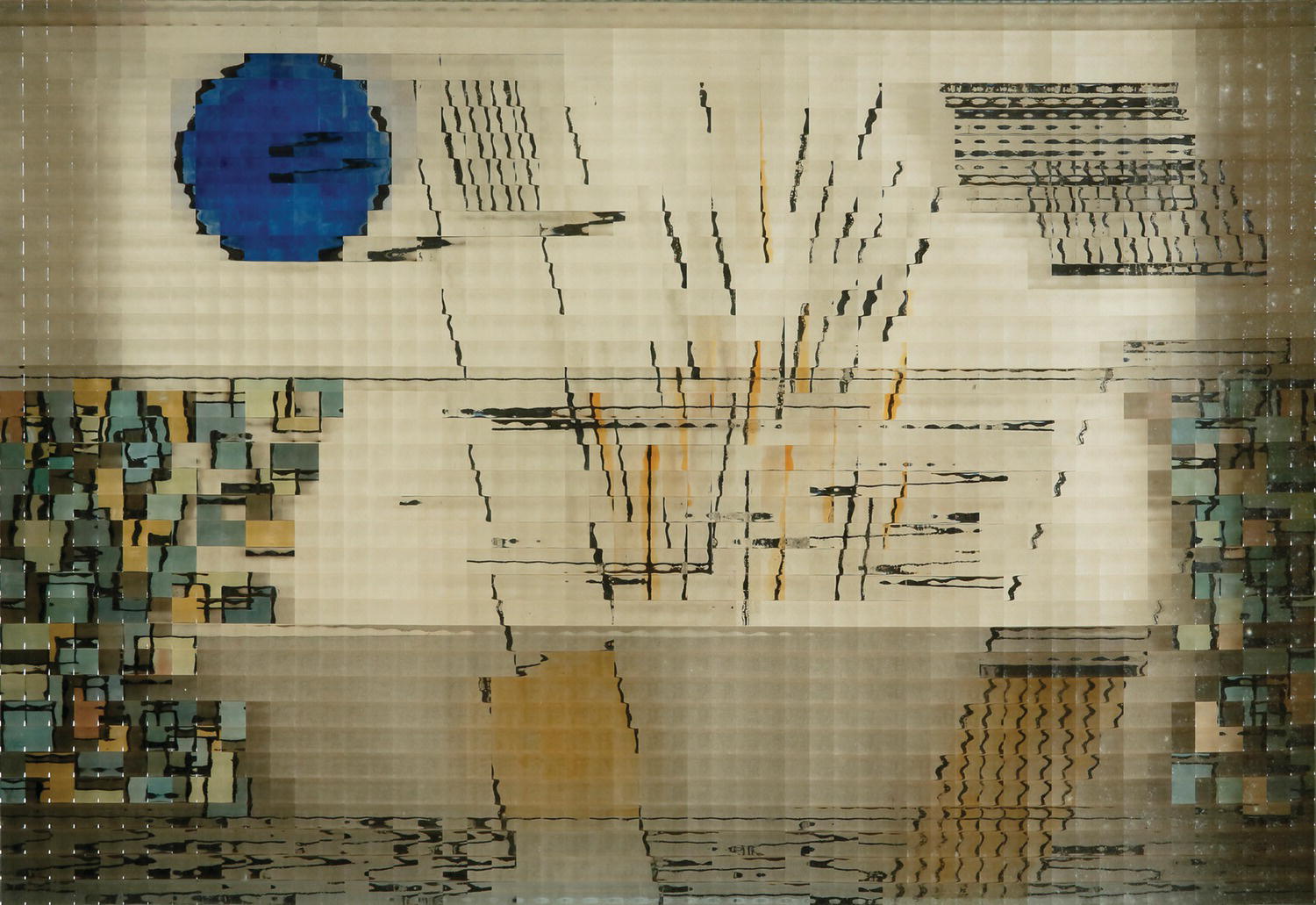

Along with Kitadai, Katsuhiro Yamaguchi played a key role in the three-dimensional space design. Apart from Lazlo Moholy-Nagy’s works and György Kepes’s Language of Vision, Frederick Kiesler’s projects—such as the stage design for Entr’acte (René Clair, Francis Picabia, 1924)—had a lifelong impact on him.36 An interest in motion, time, and space can already be observed within his Vitrine series, which started in 1952. It consists of abstract patterns painted on the surface of corrugated or slumped glass plates—an industrial material typically used for bathroom windows (Figure 4.1). Although the idea itself sounds simple, the work creates a proto-interactive optical illusion of movement as the observer moves in front of it.37

Figure 4.1 Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, Vitrine Blueplanet, 1955.

Yamaguchi’s spatial design for Jikken Kobo’s Musique Concrète/Electronic Music Audition at Yamaha Hall also involved everyday industrial materials.38 Musique concrète was developed by Pierre Schaeffer around 1950 as a new form of music based on magnetic-tape recording technology and attracted members’ attention immediately after its introduction to Japan in 1953. Yamaguchi used dozens of white strings, stretching from the middle of the seating area to the ceiling, that created geometric patterns, turning the well-known Yamaha Hall in the central part of Tokyo into an unusual space for the temporal event. The design compensated for the emptiness on stage, where machines rather than humans played back the music. Such transformation of space by a geometric and semi-transparent structure may have been inspired by Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modulator, a major influence for Yamaguchi. Innovative use of industrial materials is one of the features Jikken Kobo members share with today’s media artists. The Bauhaus spirit and the aesthetics of Oskar Schlemmer and Nicolas Schoeffer are strongly felt in the early works by Jikken Kobo, but they went beyond these influences.

For self-taught young artists who aspired to the spirit of democracy after the war, the “sense of gravity in plastic art such as painting, sculpture and architecture” was the most depressing feature of authoritative prewar art academia. Their interest in transparent or lightweight industrial material, found objects, lighting, and interactivity can be also understood from that perspective.39 Later in the 1960s Yamaguchi developed a technique for using acrylic resin in sculptures with embedded light sources developed as “order art,” that is by giving instructions for their creation to factories.40

The acrylic light sculptures were a logical consequence of his Vitrine series while “order art” was an homage to Moholy-Nagy, who in 1923 created his Construction in Enamel series by describing his designs over the telephone to a local enamel factory in Weimar. In 1966 Yamaguchi co-founded the Environment Group (Enbairamento-no-kai), which organized the exhibition From Space to Environment in the same year, in which he included a light sculpture titled Relation of C. The exhibition was meant as a precursor for the Universal Exposition 1970 in Osaka.41

The best example of Jikken Kobo’s experimental and multimedia approach is a series of surrealistic audiovisual stories they produced in 1953 by combining 35 mm slides and musique concrète, using the brand-new Automatic Slide Projector (Auto Slide) from Sony.42 The system synchronized a slide projector with a tape recorder, and was meant for educational use. Four Auto Slide works were made for their Fifth Presentation in September 1953, combining experimental music by composers and imagery by visual artists (Jikken Kōbō 2013, 84, 338).43 Yamaguchi worked with Hiroyoshi Suzuki on Adventures of the Eyes of Mr. Y.S., a Test Pilot; Hideko and Kazuo Fukushima collaborated on Foam is Created. Tales of the Unknown World was written by Takemitsu, with art direction by Kitadai and music by Suzuki and Joji Yuasa. Slides for these three works were based on sculptural constructions for each scene that were photographed by Kitadai or Kiyoji Otsuji, the photographer and experimental filmmaker. The images for Lespugue44 were not photographed but painted by Tetsuro Komai. For that piece Yuasa did an exquisite manipulation of sound elements, including ones created by piano and flute, making full use of the functions available on tape recorders. It is considered a pioneering work of musique concrète in Japan (Jikken Kōbō 2013, 84).

In parallel to the production of Auto Slide works, Jikken Kobo expanded its activities to printed media from January 1953 onwards. For the weekly Asahi Graph, a magazine published by the Asahi Newspaper Company, a photograph of an abstract structure—with the letters APN (for Asahi Picture News) included in it in some way—was created every week until February 1954. The abstract compositions’ style was similar to that of the group’s stage sets and Auto Slide works, and consisted of everyday materials and objects, such as pieces of wire, paper, wood, plastic, beads and small balls, glass containers, metal cans. The compositions were created alternately by Kitadai, Yamaguchi, Komai, and Yoshishige Saito while photography was always done by Otsuji. Later three artists outside of Jikken Kobo, including Sofu Teshigahara, the founder of the “avant-garde” Teshigahara Flower School, were invited. The series, which continued for fifty-five weeks, was the first instance of a regular and frequent distribution of avant-garde art works by mass media.

In 1955 Jikken Kobo members were involved in a series of performances named Ballet Experimental Theatre. The program included Illumination, The Prince and The Pauper, and Eve Future, with stage and costume design by Yamaguchi, Fukushima, and Kitadai, and musique concrète by Takemitsu. The stage set for Eve Future by Kitadai consisted of abstract structures that were partly movable by actors. The same year they collaborated with the radical theatre director Tetsuji Takechi45 to realize Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire as a masquerade for An Evening of Original Play by the Circular Theater. Akiyama translated Albert Giraud’s poems into Japanese, Kitadai designed the masks and the stage sets, Fukushima the costumes, and Imai did the lighting. The Noh player Hisao Kanze played the role of the Harlequin. Joji Yuasa composed for another piece from the program, “Aya no Tsuzumi” (The Damask Drum) written by the novelist Yukio Mishima, based on a classic Noh play. Such collaboration and mixing of Western and Japanese traditions was a precursor of the lively visual culture of the 1960s that included underground theatre, experimental cinema, and Butoh dance performances and often involved avant-garde artists and composers. Another project Jikken Kobo worked on at the same time was a film titled Mobile and Vitrine, featuring Kitadai’s and Yamaguchi’s works. It premiered at ACC in 1954. In the same year it was used as a backdrop projection for an act of a burlesque theatre piece at Nichigeki Music Hall titled 7 Peeping Toms from Heaven, featuring music that used sounds of hammering and a lathe (Jikken Kōbō 2013, 96).46 While the combination of avant-garde art and nude dancers might seem unusual, it was a time when a new wave of postwar humanities was spreading through the cultural sphere. Led by the philosopher Shunsuke Tsurumi, who coined the term “genkai geijutsu” (marginal art), studies of mass culture from a democratic perspective developed, covering topics within mass entertainment that had previously been neglected by academia.47

In 1955 Mobile and Vitrine was shown at a special screening of abstract films at the National Film Center. The screening included Jikken Kobo's Auto Slide works, Otsuji’s and his Graphic Group’s Kine Caligraphy, and Hans Richter’s Rhythm 21.48 For the group, film was a logical continuation of the Auto Slide works and the best medium to capture optical illusions and movements. They collaborated with the experimental filmmaker Toshio Matsumoto on Ginrin (Bicycle in Dream, 1956), a promotion film for the Japanese bicycle industry. In the film, a young boy’s dream is presented in surrealistic landscapes created by Kitadai and Yamaguchi, in a style similar to their Auto Slide, APN projects, and stage sets, while a Vitrine sometimes blurs the dream. Eiji Tsuburaya, who made the film Godzilla in 1954, was in charge of the special effects and the music was composed by Takemitsu and Suzuki. From then on Matsumoto continued to collaborate with Jikken Kobo members, especially Yuasa and Akiyama, who composed music for his films.

The group activities of Jikken Kobo ceased at the time of Takiguchi’s death in 1957, after their last group exhibition. The friendship among members continued, but, as members already had received recognition individually and were busy with their own work, they lost momentum to act as a group without their spiritual leader. Most of the members continued to be active either on solo or collaborative projects. Takemitsu composed music for more than fifty films in the 1960s alone. Yamaguchi traveled to Europe and the United States from 1961 to 1962, meeting Kiesler and Fluxus artists, and witnessing the latest movements in art including minimalism and primary structure. The experience drove Yamaguchi to further experimentation with new materials and manipulation of space, leading to the formation of the Environmental Group with architects and designers. In the 1960s Yamaguchi joined some of the Fluxus events that were co-organized by Akiyama and Ay-O. Eventually the Osaka Universal Exposition was around the corner. It involved most of the members of the group who created high-tech audiovisual environments.

Gutai Art Association (1954–1972)

Among the many artists groups active during that period, Gutai is the internationally best known, having produced works such as Atsuko Tanaka’s Electric Dress (1956) and Six Holes by Saburo Murakami (1955). Jiro Yoshihara founded Gutai in 1954 in the international and cultural town Ashiya, near Osaka. Staring in 1955, Yoshihara published newsletters called Gutai and sent them to his prewar international contacts. As a result, Gutai was noticed abroad as a Japanese equivalent of French art informel or American abstract expressionism in 1956. Among the many avant-garde artist groups of the time, Gutai was the first to be associated with international art movements and recognized outside the country.

Gutai also was the longest lasting among the postwar avant-garde art groups. Altogether almost sixty artists joined Gutai during its nearly two decades of activity that ended with the death of Yoshihara in 1972. In contrast to Jikken Kobo, Gutai was a solid “group” with declared membership. The Gutai Art Manifesto, published in 1956, stated the goals of the group, which functioned under Yoshihara’s strong leadership. The activities of Gutai can be divided into three phases.49

Beginnings of Gutai

Yoshihara, the heir of a leading cooking oil company, was a recognized avant-garde painter in the prewar era. Although he studied business instead of art he was accepted into the Nika exhibition at the age of 29 and, in 1938, joined the newly added “Room 9” for avant-garde art. In 1937 he helped traveling the Surrealist Paintings from Abroad exhibition to Osaka and shared a panel with Takiguchi, who had co-organized the show. After the war Yoshihara became a key figure in the cultural community of the Kansai region. He assisted in relaunching Nika and served as its representative in Kansai; founded and became the chair of the Ashiya City Art Association in 1948;50 and, in 1952, co-founded an interdisciplinary art organization that became known as “Genbi.” Its monthly meetings were joined by a wide variety of local cultural figures such as painters, sculptors, designers, and calligraphy and flower arrangement artists. Yoshihara himself did stage designs for performances and fashion shows in Ashiya, and Genbi organized five exhibitions, with more than two hundred artists participating, until 1957. Yoshihara’s background as a businessman presumably helped him in organizing projects with a strong leadership. Given all of these activities, it seemed a logical step for Yoshihara to establish his own group. By 1947 Shozo Shimamoto and others were frequenting Yoshihara’s house, bringing their works and asking for critique. Other groups had started to appear in Kansai, including Zero-kai (Zero Group). In 1954 Gutai was officially formed with members chosen by Yoshihara.51 The core members of Zero-kai—Murakami, Tanaka, Akira Kanayama, and Kazuo Shiraga—joined Gutai in 1955.52 The publication of the bilingual Gutai journal in January 1955 was a significant step in achieving the international recognition that Gutai would receive. On March 12 of the same year, the Gutai artists submitted their works to the 7th Yomiuri Indépendant in Tokyo. All the works were simply titled Gutai, in line with Yoshihara’s concept of pursuing abstraction. It was Gutai’s first and last massive participation in the Indépendant. After that, the Gutai artists separated themselves from the most active avant-garde artists who had gathered around the non-juried competition. Did Yoshihara find the messy Indépendant inappropriate for his group? Or, was it because the art community in Kansai was smaller and more exclusive compared to the one in Tokyo? It seems that Yoshihara believed in the value of closed groups and juried exhibitions such as Nika, while more radical critics such as Takiguchi tried to change the system and realize democracy in art.53 Gutai was actively involved in the scene of modern art, as their list of exhibition illustrates, while Jikken Kobo members did not care if they were making art or not. Experimentalism and an interest in science and technology can be observed in the activities of early Gutai members, but did not develop further.

The first phase of Gutai: 1954–1957

The most unusual and original Gutai works were created between the group’s first and legendary outdoor exhibition titled Experimental Outdoor Exhibition of Modern Art to Challenge the Midsummer Sun in Ashiya Park in the summer of 1955 and Gutai Art on the Stage in July 1957. The outdoor exhibition inspired members to think differently about art making.54 No one cared about preserving or selling the work after the show, and everyone tried to attract the most attention. The need to create large-scale pieces within a limited budget led to the choice of unusual materials. Everyone was enthusiastic about their respective ideas, including impossible or dangerous ones. Having a leader who made the final decision was a necessity.55 Concepts such as interventions into the environment, interactivity, and participation by visitors were pursued because of the nature and scale of the park with nearly five hundred pine trees, stretching along a river. In October of 1955, the 1st Gutai Art Exhibition took place at Ohara Kaikan Hall in Tokyo.56 This time the challenge was to surprise the Tokyo audience who were familiar with avant-garde art through Yomiuri Indépendant and other exhibitions. Murakami’s Making Six Holes in One Moment, in which he stretched layers of packaging paper over two wooden frames and tore through them six times, and Shiraga’s Challenging Mud, in which he thrashed around in a heap of building clay for twenty minutes, surely shocked visitors.

Among the legendary pieces from the period were Tanaka’s Work (Bell) (1955), Shiraga’s Please Come In (1955),57 and Shimamoto’s Please Walk on Here (1956)58—all strongly focused on visitor participation, which was unusual in contemporary art at the time. Tanaka’s Work (Bell) was a sound installation—consisting of a string of electric bells laid out around the gallery—that could be experienced only when a visitor pushed a button for a certain period of time to set off a chain of rings (Figure 4.2). A series of electric bells connected to a control panel was placed along the border of the exhibition space. Tanaka designed the wooden control panel, which was placed on the turntable of a record player. Touch switches were carefully placed on the board in the shape of a heart (i.e., a variation of cycloid), with each switch corresponding to a bell. As a visitor pushed a button the panel would rotate, and the bells would start ringing one after another, producing a continuum of an alarming sound traveling through the exhibition space. Work (Bell) was shown at the 3rd Genbi Exhibition in Kyoto in 1955.

Figure 4.2 Atsuko Tanaka, Work (Bell), 1955/2005.

Photo: Seiji Shibuya. Photo courtesy of NTT InterCommunication Center (ICC).

Shiraga’s Please Come In consisted of a structure made of logs bound together at the top. Visitors were invited to come inside the open structure to contemplate the sky and surrounding trees. Shimamoto asked for more involvement from the visitors. His installation consisted of long, box-like pathways made of colored wooden blocks. A notice read: “Please walk on top of it. Shozo Shimamoto.” The wooden floors started wobbling as visitors walked on them since the artist had installed springs underneath the blocks to make them unstable. Using simple technology he created an interactive kinetic sculpture involving visitors’ bodies.59

During the 2nd Gutai Outdoor Exhibition in Ashiya Park in 1956, a big wooden panel together with paint and markers for free use was installed. A small sign said, “Rakugaki-ban: Please draw freely” (“rakugaki-ban” means a board offered for graffiti) without attributing the work to any artist. In the 5th volume of the Gutai periodical, which reported on the outdoor exhibition, the board was featured only as a “Scribbling Board” in the “Snap” section, which presented snapshots taken by group members and visitors to the outdoor exhibition. The work raised the question whether it was meant as an artwork, or was just a service offered to the public, especially for children. The piece later was officially named Please Draw Freely when it was shown at the Nul international art exhibition in Hague in 1966, to which Gutai had been invited. Whether the piece was originally meant as an artwork or not, Yoshihara defined it as art by then.60

One might ask how and why such an idea—which almost anticipated interactive art or the net art of the 1990s that offered free (online) spaces for virtual drawing—was conceived and realized. The answer may lie in Gutai’s involvement in children’s drawing. In late 1947 Yoshihara was contacted by an editor of a children’s poetry and art magazine titled Kirin.61 The editor himself, Yozo Ukita, joined Gutai. Gutai members contributed their works and writings to the magazine and were involved in competitions of children’s paintings. Like many other young painters, Gutai members often earned their living by teaching painting to children. When members later on were asked about influences from abroad that had influenced their work, they would answer that they were inspired by children’s drawings, not by international art movements. Respect for the originality of children’s drawing was in accord with Yoshihara’s famous doctrine to respect originality above anything else.62 Originality was the criterion he applied in selecting members’ works, and even the repetition of one’s own original ideas was rejected (Murakami 1994, 213).63 This generated an explosive production of original works, as Atsuko Tanaka’s projects illustrate.

Tanaka, who used to produce rather minimal works before joining Gutai, discovered industrial textile as a cheap material for creating structures in outdoor space. A huge piece of thin cloth in vivid pink would change its form in the wind. Tanaka’s interest in transforming space continued in indoor pieces such as Work (Bell) for which she designed the electric circuit herself and appropriated regular house bells and a record player, anticipating the “circuit bending” practices of today’s media artists. She continued using electric wiring for the outdoor exhibition in 1956, employing light bulbs and changing light intensity through the use of water. In her best known work Electric Dress (1956)64 she connected light bulbs painted in vivid red, yellow, green, and blue to form a dress, which she wore as performer. The bulbs flashed, and, together with the wiring, made the dress extremely heavy. There was the danger of getting an electric shock if cables came loose. Yoshihara’s doctrine along with technical advice from Kanayama, whom she later married, must have encouraged her, yet it involved significant risk-taking for a young female artist to realize the piece.

The above-mentioned works show Tanaka’s interest in creating projects that move, change, and interact with the environment. Her experience with using textile became the basis for her Stage Clothes (Butai-fuku, 1957) performance. The dress she had designed and wore continued to dramatically transform as she removed its parts, one after another, on stage. The extremely complex design of the cloth and performance proved her talent in designing a layered but logical system through the use of either electrical circuits or purely physical representations. However, Stage Clothes marked Tanaka's departure from technology. From 1957 onwards Tanaka concentrated on abstract paintings based on drawings she had done for designing electric circuits. Her interest in movement was occasionally realized in the form of figures painted on large circular wooden panels that rotated, driven by motors, and were installed in her garden. In the film Round on Sand, Tanaka is seen drawing these types of lines and figures on the beach, and the waves wash them away.65

The interest in technology, new material, and scientific phenomena was shared by some of the Gutai members, including Jiro Yoshihara, who created light sculptures for outdoor exhibitions, and his son Michio Yoshihara, who applied musique concrète in their stage performances. Sadamasa Motonaga suspended plastic bags—a new material at the time—filled with colored water for the outdoor exhibitions.

Among the technically most advanced members of Gutai was Kanayama, who experimented with industrial materials such as inflatable balloons and plastic sheets. His Footprints (1956) was an installation using long white plastic sheets with black “footprints,” laid on the floor of the exhibition venue or on the ground (if exhibited outdoors), and inviting visitors to walk on it. However, the imaginary walker’s footprints would leave the visitors behind when the sheet would “climb up” a wall or a tree, revealing the work’s three-dimensional nature. Kanayama’s Work series, produced mostly around 1957, was created by means of a remote-controlled toy car with paint tanks. The artist built, modified, and drove around the car on a sheet laid on the floor. Neither its trajectory nor the resulting traces of ink were fully controllable. Kanayama tested a variety of crayons, markers, black and color inks that were scribbled or dripped by the car over large pieces of paper and later white vinyl sheets, which the artist found to be most appropriate for his purpose. The result was a series of complex line drawings—traces of an entangled relationship between the artist and the machine, control and chance operation.

“Painting through action” was an experimental practice shared by early Gutai members, among them Murakami who created sensational performances by running through paper screens. Shiraga, who performed Challenging Mud in 1955, continued to use his own body in his work, often painting with his feet while swinging on a rope hung from the ceiling. Michio Yoshihara used a bicycle for drawing. Shimamoto painted on large canvases, first by throwing glass bottles filled with paint, and later using a cannon and even a helicopter. One has to wonder whether Gutai members saw their work in the tradition of publicly performing calligraphy or calligraphic painting, which had existed since the Edo era.66

The second phase of Gutai: 1957–1965

As Yoshihara and Shimamoto kept sending their bilingual journal Gutai abroad in 1956, the group started gaining international recognition. In April, LIFE magazine sent two photographers to shoot images for an article on Gutai.67 The journal also reached Michel Tapié, the French critic and theorist who coined and promoted the concept of art informel. Recognizing Gutai as the Japanese version of art informel, Tapié, together with the painter Georges Mathieu, visited Gutai in September 1957. Being part of international movements meant a lot to Japanese artists at that time. Yoshihara decided to follow Tapié’s suggestion to exhibit Gutai abroad and introduce art informel in Japan. Gutai members began focusing on the creation of paintings, instead of experimenting or performing, for practical reasons—to be able to ship, exhibit, and sell, as Tapié also was an art dealer.

In 1958, a Gutai Group Exhibition took place in New York’s Martha Jackson Gallery. In the spring of that year, a hundred copies of Gutai Vol. 8—co-edited by Yoshihara and Tapié—were sent to a bookstore in New York and were “sold out in a few days” (Kato 2010, 104). However, their works were (mis-)interpreted and contextualized as manifestations of informel or abstract expressionism. The press release of the exhibition introduced Gutai as an “informal gathering” that aimed at “embodiment of spirit” and took inspiration from “new American painting,” especially from Jackson Pollock (Kato 2010, 106). This was especially unfortunate for Kanayama whose Work series was understood as mere mimicry of Pollock. The same year Shimamoto made a seven-minute color film with sound, titled Work, by painting directly on film, but otherwise experiments became rare.68

The International Sky Festival in 1960 was an exceptionally unique exhibition in the second phase of Gutai. Air balloons—a typical medium for advertisements during that era – featuring paintings by Gutai and international artists from Italy, Spain, and the United States floated in the air above the roof of the Takashimaya Department Store in Osaka for a week.69 Another interesting work of that time was the interactive Gutai Card Box, which was installed in the gallery space of the Takashimaya Department Store for the 11th Gutai Art Exhibition in April 1962. By inserting a coin into an automatic vending machine, each visitor would get an original artwork painted by a Gutai member. Created before the arrival of Fluxus, the project was ahead of its time and its venue (a department store) made it even more interesting. The Gutai Card Box actually was not a machine, but had a human hiding inside who would do the drawings.70 Shiraga and Murakami recall that the quality of the card depended on “human factors.” Male members tended to draw better if the client was a young woman (Murakami 1994, 218).

Gutai’s focus on painting was enhanced when Gutai Pinacotheca, a permanent exhibition space named by Tapié, opened in the central part of Osaka in 1962 in the old warehouse of the Yoshihara Oil Mill. Compared to the times when the artists had to work hard on filling the vast space of Ashiya Park, hoping their pieces would last for a week or two, the gallery made exhibiting much easier, but it also left little space for experimenting. Tanaka and Kanayama left Gutai in 1965 just when the invitations to take part in the Osaka Expo ’70 split the artworld. In their studio in Nara, Tanaka focused on her paintings inspired by circuit designs from her earlier works. Kanayama stayed away from presenting artworks until the late 1980s, and his later works involved artistic visualizations of sound waves and astronomical data.

The third phase and end of Gutai: 1965 to 1972

Given that Gutai was based in the Osaka area and internationally recognized and Yoshihara was a member of the region’s business and cultural communities, there were reasons for the group to get involved in the 1970 Expo.71 In parallel with the official art exhibition, which included selected members of the group, the Gutai Group Exhibition was realized with a unique exhibition design by a new member, Senkichiro Nasaka, who used metal pipes to create a visual structure for hanging paintings. Another new member, Minoru Yoshida, contributed his large-scale optoelectronic sculptures to the show. Furthermore, Gutai group performances took place on the main Festival Plaza in front of Taro Okamoto’s Sun Tower, reviving some of the experimental practices in which the group had engaged in its earliest stages. New members with advanced technical skills played a major role in the group exhibition and the spectacular stage performances. One might ask what initiated these changes after years of more conventional practices consisting of images displayed on gallery walls.

In April 1965, Jiro Yoshihara and his son Michio visited Amsterdam to install Gutai artworks at the Stedelijk Museum for the international exhibition Nul 1965. The exhibition was organized by the Nul group founder Henk Peeters and was based on his network of European avant-garde artist groups, such as the French GRAV and the Italian Gruppo N and Gruppo T, and artists including Otto Piene. When the Yoshiharas arrived “with a suitcase full of paintings and sketches for new installations,” Peeters surprised them by rejecting the paintings as being “too informel” (Munroe 2013, 35). Kanayama’s inflatable vinyl air sculpture Balloon, which they had brought in the suitcase, was accepted, but, other than that, they were asked to reconstruct early Gutai works on site, including Murakami’s Work (Six Holes) and Shimamoto’s Please Walk on Here, by using locally available materials. As a result, Gutai’s works were, probably for the first time, internationally presented and received within the right context, side by side with works by artists from various countries that represented experimental and challenging approaches. This experience made Yoshihara reconsider the policy he had adopted since 1957. The “informel fever” was over in Japan at that point, and the forthcoming Osaka Expo would become a new stage for technological art forms.

By the end of the same year Yoshihara invited quite a few younger artists to join the group, which was unusual in Gutai’s history. His hope to bring back an experimental spirit to the group was obvious, and the effect became immediately visible. In 1966, Toshio Yoshida developed a machine that produced soap bubbles as a sculpture, which was shown at the 19th Gutai Group Exhibition in 1967. The 19th exhibition showcased a number of kinetic and light artworks consciously responding to the movement of “environment art,” including kinetic sculptures by the youngest member, Norio Imai.72 The introduction of a darkened room for light art was a new development for art exhibitions. Minoru Yoshida, whose background was painting, became known for kinetic sculptures using motors and industrial materials such as fluorescent acryl. He and Nasaka were invited to Electromagica: International Psytech Art Exhibition ’69, held at the Sony Building in Tokyo, along with artists including Nicholas Schöffer and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi. The Electromagica exhibition was meant as a pre-event for the Expo and aimed at presenting new methods and forms of art and design in the era of electronics, in which “cohabitation of human and machine is needed,” echoing the theme of the Expo that called for “Progress and Harmony for Mankind.”73 Gutai at that point was regaining its experimental spirit and trying to bridge art, design, and technology.

Yoshida’s iconic work Bisexual Flower (1969), a large kinetic sculpture incorporating sound, was made of yellow-green, transparent, fluorescent plexiglass, ultraviolet tubes, motors, and electronic circuits. Petal-like elements made of plexiglass moved as neon-colored water flowed through transparent plastic tubes. The entire sculpture glowed in a darkened space. Even today the piece fully functions and is strikingly impressive. The unprecedented kinetic sculpture was shown at the Expo along with three other works by Yoshida, including a transparent car, but the artist himself was not present. Yoshida felt uncomfortable with being part of the Expo while the political meanings of the event were argued about and criticized among young artists. Tired of conflicts, Yoshida left Japan before the Expo opened and moved to the United States.74

Toward the end of the Expo, from August 31 to September 2, a group performance titled Gutai Art Festival: Drama of Man and Matter took place on the Festival Plaza. It combined elements from Gutai’s previous stage performances, such as balloons, smoke, bubbles, light, sound, dancers in designed costumes, as well as kinetic sculptures. Nasaka designed the major structure. Sadaharu Horio created an installation made of fabric, which responded to the general interest in environmental design. Yoshida’s transparent car appeared on the stage and robots were also present, yet they were not controlled by means of sophisticated technology. A box that magically moved and finally fell, for example, was operated by a student inside—similar to the earlier Gutai Card Box. After Yoshida left, the technical skills of the group were more limited.

The Expo could have served as a springboard for the group. Instead it created stress and disagreements among the members. Due to the rapid increase in new members, the group’s identity was no longer clearly defined. Older key members, such as Shimamoto, Murakami, and Motonaga, left Gutai in 1971. Although the Gutai Mini Pinacotheca, a smaller reincarnation of the original Pinacotheca, which closed in 1970, opened in Osaka in October 1971, not much activity took place after the Expo. With the unexpected death of Yoshihara in 1972 the group disintegrated.

Cross-genre, Intermedia, and Sogetsu Art Center

The latest international art movements were introduced in Japan in the early 1960s. The most sensational event were the performances by John Cage and David Tudor at the Sogetsu Art Center in 1962. Yoko Ono, who had already been active as an avant-garde artist in New York, and the young composer Toshi Ichiyanagi, who was a student of John Cage, helped realize Cage’s and Tudor’s visit to Tokyo.

As previously indicated, 1960s Japan saw an incredibly rich variety of experimental art activities. Japan was part of an international phenomenon, as the Fluxus events organized by the avant-garde artist Ay-O and ex-Jikken Kobo members Yamaguchi and Akiyama illustrate, but, at the same time, distinctly Japanese elements rooted in more traditional aesthetics started to appear. New forms of art, such as Butoh and the underground theatres organized by Shuji Terayama and Juro Kara, among others, reflected both the international rise of underground culture and the prewar (or even pre-Meiji Restoration) mass entertainment tradition. “Japan-ness” was rediscovered and woven into the underground culture, for example in the posters designed by Tadanori Yokoo and Kiyoshi Awazu for underground theatres and experimental films. Experimental film directors, including Nagisa Oshima, founded the Art Theatre Guild (ATG), a membership organization that supported the production of independent cinema. Photographer Eiko Hosoe, for whom the writer Yukio Mishima modeled nude, took close-up pictures of 1960s cultural figures including Butoh dancers, creating a new genre in Japanese photography.

“Midnight entertainment” TV programs also launched in the 1960s, bringing a glimpse of radical avant-garde art to the living room through the artists invited to the shows. Yoji Kuri was among the regular guests and introduced his experimental short animations, which could be either ironical, nonsensical, or surrealistic. The merger of popular entertainment and art was also taking place in manga. The independent comic magazine Garo, which launched in 1964, played an important role in the rise of alternative and avant-garde manga, Yoshiharu Tsuge’s “surrealistic” manga being an example. These people with very different backgrounds would eventually form a wide network—also including editors, writers, and TV producers of cultural programs—which made it possible to organize cross-genre activities. “Intermedia” became the keyword of the 1960s and early 1970s, encompassing the wide range of art, design, illustration, music, literature, theatre, architecture, film, video, animation, entertainment, and more.

It was symbolized by Sogetsu Art Center, which opened in 1958 in the central part of Tokyo. It served as a hub for experimental art through the 1960s.75 Sofu Teshigahara had founded Sogetsu School before the war, redefining flower arrangement as free form spatial sculpture rather than a set of rules for arranging flowers, and introduced industrial materials that had never been used before. His son, the experimental filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara, operated Sogetsu Art Center as the director until April 1971.76 Concerts, screenings, and lectures took place almost every weekend during high season, with Sogetsu Cinematheque often focusing on underground cinema, Sogetsu Animation Festival introducing art animation, and the concert series featuring contemporary composers.77 In 1969, Sogetsu Art Center collaborated with the American Culture Center (ACC) to introduce works by Stan VanDerBeek on the occasion of his visit for the Cross Talk Intermedia event.

Cross Talk Intermedia, a three-day event that took place in Tokyo in the huge Yoyogi Gymnasium in 1969, was sponsored by ACC as an attempt to create a dialogue between Japanese and American “intermedia.” Catalogue essays were contributed by John Cage, Buckminster Fuller, Peter Yates, Taro Okamoto, Shuzo Takiguchi, Kenzo Tange, Gordon Mumma, and Stan VanDerBeek, and works by Cage, Mumma, and VanDerBeek were performed along with those by other American and Japanese artists. The long list of artists and composers included names such as Matsumoto, Yuasa, Akiyama, Ichiyanagi, and Takemitsu, as well as other avant-garde artists, such as Takahiko Iimura and Mieko Shiomi who had joined New York Fluxus. Butoh dancer Tatsumi Hijikata also performed. Both visual artists and composers attempted to fill the space, be it with multiscreen projections or multiple tape decks. Robert Ashley’s sound piece That Morning Thing included audience participation. Former Jikken Kobo members Akiyama and Yuasa enthusiastically volunteered to realize the event, collaborating with Roger Reynolds. Imai was the lighting director and Yamaguchi collaborated on the set design. Cross Talk Intermedia became possible through an international network of avant-garde artists, and the former Jikken Kobo members formed its hub in Japan.78 It also was a prelude to the Expo ’70.

Osaka Expo ’70

The 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo were an important step in recovering the nation’s pride and international presence. Following their success, a plan to realize the Universal Exposition in Osaka in 1970 was immediately developed and confirmed in 1965. There were several reasons why the “Expo” was needed, international promotion of Japan’s economic growth being one of them and redevelopment of Osaka another.79 The Expo was considered a stage for demonstrating the power of science and technology to the public. But the situation also was more complex; the renewal of the permanent version of the US–Japan Treaty (“Anpo”) was to take place in 1970, and there were expectations of a strong opposition similar to that in 1960. Those who opposed the Treaty suspected the Expo was meant as a spectacle to divert people’s attention from political issues. Due to the opposition against the war in Vietnam and student struggles in many universities, following the May 1968 student revolt, streets in big cities were no longer quiet.80

From its earliest stages, the Expo project was led by a group of architects who had promoted Metabolism, a highly conceptual architectural movement since the beginning of the 1960s. Transforming the hills covered by tall bamboo shrubs into a large, completely artificial and temporal “future city” presumably was a dream project for them.81 The most established architect of the time, Kenzo Tange, was appointed as producer of the main facilities.82 Tange invited Taro Okamoto to be the producer of the thematic exhibition. Okamoto initially hesitated to be a part of the nationalistic event, but accepted the role.as a practice of his concept of dualism or Polar Opposites, which suggested that new art forms would be born only from emphasizing contradictions or conflicts rather than synthesizing them.83 The participation of Okamoto created confusion in the avant-garde art world, which had lost momentum with the cancellation of Yomiuri Indépendant in 1964. Should artists consider the Expo as a rare opportunity to realize their ideas and earn money? Was it acceptable for artists to serve the industry and support such a national event?

The theme of the Expo was “Progress and Harmony for Mankind,” but it definitely did not create harmony in the avant-garde art world. In the second half of the 1960s avant-garde artists were split into three groups. Artists and composers who used new technology, especially the former members of Jikken Kobo, became actively involved in the Expo. Others kept their distance from the Expo, among them Tanaka and Kanayama, who left Gutai and concentrated on painting in their house in Nara, and artists who had left Japan. The third group of artists and art students severely criticized the Expo as a showcase of capitalism and a spectacle meant to distract people from the social and political problems in real life. They argued that artists should not take part in such a scheme. While some performed happenings and others organized “anti-Expo” art events, the situation gave birth to a new critical wave among young artists. Best known among them is the group of students from Tama Art University, which included Yasunao Tone who formed a group named Bikyoto (Bijutsuka Kyoto Kaigi, or Artists’ Joint-Struggle Council) that developed more theoretically oriented activities.84

In spite of the protests and hot debates, pavilions by leading corporations and industrial associations featured unusual structures filled with image, sound, and optical effects, realized through contributions by young architects, artists, designers, filmmakers, and composers. There was a high demand for avant-garde artists since they typically were ahead of their time when it came to imagination and experience in using the latest technologies and realizing futuristic space. The “intermedia” atmosphere of the 1960s had already created a loose but effective network that nurtured collaborations. For people in this network the Expo was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and a challenge, accompanied by a much bigger fee than they could normally earn with their artworks. When invited they agreed to participate. If Okamoto had accepted the role, why shouldn’t they? The Pepsi Pavilion, designed by the members of E.A.T., and covered in a fog sculpture by Japanese E.A.T. member Fujiko Nakaya, was one of the most experimental pavilions with an open-ended, interactive design. The Mitsui Group Pavilion, designed by Yamaguchi, anticipated today’s motion rides by creating three movable decks, each carrying twenty visitors, suspended in the air. The young architect Arata Isozaki, a regular member of Neo-Dada meetings, took on major responsibilities in the system design of the main pavilion, which included two robots.

A most unusual pavilion was designed by the experimental filmmaker Toshio Matsumoto, who had earlier directed Bicycle in Dream with Jikken Kobo. As a freelance film director he was known for highly experimental short films created during the 1960s—both for advertising and publicity and as personal artworks—including For The Damaged Right Eye, a multi-projection short film. A collage of footage documenting anti-Anpo demonstrations and scenes from the entertainment districts of Shinjuku were shown on three screens. The work was both an artistic engagement with the political situation of the time and an experiment in deconstructing time and space by juxtaposing two parallel scenes coexisting in Tokyo in 1968. Matsumoto was nominated as director for the Textile Pavilions while shooting the feature film Funeral Parade of Roses, a landmark piece in Japanese avant-garde cinema.85 His team for the Expo consisted of avant-garde artists: Tadanori Yokoo created the exterior and interior, both done in red, with the exterior half covered by a scaffold-like structure as if the pavilion was still under construction; The Neo-Dada artist Masunobu Yoshimura modeled a number of plastic ravens that were positioned on the scaffold along with a few life-size human figures who looked like workers. Inside the pavilion, life-size “butler” figures, all identical and designed by the doll artist Simon Yotsuya, welcomed the visitors. Matsumoto himself created a multiscreen space showing an ordinary day in the life of a young lady named Ako. Sound and lighting effects were designed by the former Jikken Kobo members Akiyama and Imai.

All in all, it was a surrealist installation. It is not clear whether the client (the textile industry association) was exactly happy with the outcome, but they had given Matsumoto and Yokoo permission to do whatever they wanted to do, and the artists took advantage of it. Why did they choose to create such an uneasy atmosphere for the pavilion, with its red scaffold, ravens, and “workers” on the roof? As a filmmaker who had worked with the industry for years and already was famous for a style combining artistic qualities with functionality—which presumably was a reason for choosing him—working with the industry itself could not have been an ethical problem for Matsumoto. At the same time the nature of the Expo and the political problems surrounding it must have bothered him, since he was also a theorist. The uneasy and unfinished look inside and outside the pavilion could be interpreted as a metaphorical refusal of the artists involved to complete the tasks given to them by the industry.

As mentioned earlier, Japanese postwar avant-garde art was inseparable from the social and political situation of the era. In a sense the artists participating in the Expo were used for creating propaganda, the illusion of infinite economical growth supported by future technologies. As an artistic resistance to such agenda, Matsumoto’s Textile Pavilion perhaps was an exception. Most of the participating artists had to face the fact that art was consumed as a mass entertainment, as a part of a spectacle in the sense of Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1967).

One reason for involving avant-garde artists in the Expo was the relationship between being avant-garde and being experimental. While being “avant-garde” implied a certain attitude confronting the establishment or tradition, being “experimental” meant the exploration of new methods, materials, or tools that had not yet been known in art making. When new materials and tools such as tape recorders, electronic devices, and computers appeared in the 1950s and 1960s, experimentation with new technologies or materials often required collaboration with engineers or researchers coming from the industry. At the same time, the industry was interested in discovering new possibilities for their products or technologies through artistic imagination. Though still small in scale, Jikken Kobo’s works using Auto Slide were examples of such a collaboration between artists and engineers. When the scale of the experiment expands and the technology is very specialized or expensive, collaboration extends beyond a small group of people, which frequently happens in today’s media art as well.

One might still raise the questions why artists did take part in a nationalistic event sponsored by the government and whether they were indifferent to political issues. While it will be impossible to definitively answer them, the distance that Jikken Kobo and Gutai artists kept from politics or social issues can be better understood when considering the social and political turbulence around them. They were surrounded by politics, including proletarian art movements and hierarchical academic art. Still, considering the contrast between French and Japanese surrealists, one has to ask whether the tendency to avoid social or political issues has a tradition in Japanese art.

East Asian Avant-garde Art after World War II

In other parts of Asia the birth of avant-garde art and subsequently media art took much longer. The following is a brief overview of art developments in China and Korea. An in-depth exploration is beyond the scope of this chapter; it would require another text to discuss details of experimental film and video in Hong Kong alone, for example.

China after the War

When World War II was over and the Japanese occupation ended in 1945, drastic changes took place in China and Korea. Following the immediate political confusion after the war, the Cold War brought a continuous tension to East Asia.

In China, the Communist Party led by Mao Zedong fought against the Chinese Nationalist Party. The civil war ended in1949 as Mao took hold of Mainland China and the Nationalist Party moved to Taiwan. At that time most of China was far from being modernized. From 1958 to 1961, Mao’s Great Leap Forward campaign was carried out, aiming for a rapid transformation of the country’s industry and agriculture. The unrealistic plan collapsed, resulting in the Great Chinese Famine. To regain his political power Mao launched the Cultural Revolution, which lasted from 1966 to 1976. Many artists and cultural figures were expelled from the cities and sent to remote farming villages for labor. Any “anti-communist” activities or expressions were severely punished. During these campaigns, much of the historical and cultural assets were destroyed and Western art books were confiscated. Art teachers and painters used to study either in Europe or in Japan before the war and were familiar with the latest trends in the artworld, but three decades after the war there was no information flow on modern or contemporary art from the West. Art education was focused on realism, based on European classical academic styles, and meant to serve communist propaganda. Painters found themselves under censorship, and there was no space for experimental art.

In late 1970s, economic reform started and open policies set in. Only then did Western modern and contemporary art became accessible, inspiring young artists to experiment with new forms of art. A 1979 outdoor exhibition by a group of avant-garde artists named Star (Xingxing) Group, founded by twelve principal members including Ai Weiwei, was a major breakthrough.86 It was followed in the 1980s by various experiments by different groups, which were referred to as the “85 Art Movement” or “85 Art New Wave.”87 An epoch-making exhibition of Robert Rauschenberg’s work took place in the Beijing National Gallery in 1985. A most radical art group called Xiamen Dada, led by Huang Yong Ping, was founded in 1986. The China/Avant-Garde exhibition in 1989 at the National Gallery was a seminal event that concluded the era of Chinese avant-garde art, showing more than three hundred works from more than a hundred artists.88 In the same year the democracy movement came to a halt in Tiananmen Square and at the same time China experienced an economic boom.

In the 1990s Chinese contemporary art started to flourish with Political Pop and Cynical Realism as mainstream approaches. With the rapid increase of international interest in Chinese art, contemporary art finally gained more status and recognition within the country, encouraging young artists to explore new media such as computer graphics and animation. Feng Mengbo (b.1966) belongs to the new generation of artists who work with new media technology. He became internationally recognized through the interactive piece My Private Album shown at DOCUMENTA X in 1997, and the video-game-based Q4U shown at DOCUMENTA XI in 2002.

During the long period of confusion in China itself, some Chinese-born artists were very active abroad. Wen-Ying Tsai is known as a pioneer in cybernetic art who combined kinetic sculpture and stroboscopic light, often using sound from the environment as the “input” to a cybernetic system. Tsai, born in China in 1928, moved to the United States in 1950. When the Cultural Revolution came to a halt Tsai contributed to helping young Chinese artists to show their work outside the country.

Korea after the War