CHAPTER ELEVEN

Give a Gift When You Complain

Scotland faced the same issue many countries worldwide confronted during the COVID-19 pandemic—complaining customers who got in the faces of service staff, threatened, and even physically attacked essential workers. In response, the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman offered advice to people handling complaints that involved going beyond calling the police to arrest and charge such customers with breaking laws.

The Ombudsman’s advice was almost a plea to everyone to return to long-gone good old days and maintain a civil people-centered approach, even with potentially dangerous customers. This advice from the Ombudsman seems rather quaint compared to the reality of how some customers behaved during the pandemic. The Ombudsman recommended listening with respect and kindness, not labeling customers as “vexatious” or judging their behavior. Because customers are probably unhappy and stressed, it suggested excusing negative behavior even when on the nasty side. The Ombudsman encouraged both staff and customers to “engage positively with each other.”1 It wasn’t bad advice, but it makes one yearn for those days when customers were mainly kind and sympathetic to workers, grateful that stores were open and shelves were fully stocked and service staff was adequate enough to meet their needs.

The partnership needs to go both ways. We’ve talked about the responsibility of CSRs to seek satisfactory solutions to customer issues—but customers also have a role to play. If customers want an acceptable solution to their problems, it’s advantageous for them to manage their behavior and not alienate people attempting to assist them. Complaint handlers have a lot of power regarding how complaining customers are treated and compensated, and it doesn’t always work for customers to attack CSRs. John Goodman, who has completed more customer service research than just about anyone and is the author of Strategic Customer Service, says that most CSRs come to work to do a good job. He estimates complaint handlers’ attitudes or errors cause about 20 percent of customer dissatisfaction.2 But it happens. I have been upgraded to first class on airplane flights by gate agents because I was friendly and empathetic to their situation caused by a mad mob screaming at them. None of them were upgraded, and several didn’t get a boarding pass.

There are no easy solutions here. We cannot rely solely on CSRs to stop customers from doing what many do: making enemies out of people whose job is to help them. It’s possible as many as one-third of customers are not easy to help. Think about that—that’s one in three customers!

CSRs have to be proactive, starting by letting upset customers know they are on their side, even when they are hostile and use unsettling language. We’ve covered this, and the strategies and techniques identified in this book will help. Of course, if you as a service provider feel that someone is likely to explode and become physically dangerous, it’s time to get help. We can’t say that often enough.

But beyond attempting to manage a complaint before it gets out of control, we all need to take responsibility for how we behave when complaining. If you believe customers have the right to act any way they want because they are “the customer,” then this message is not for you. It will bump right into your beliefs. But if you want to be a successful complaining customer instead of someone just blowing off steam and likely reducing your chances to get what you want, you can do a few things to be successful at it.

How to Engage with a Complaint Handler

A successful engagement between complainers and complaint handlers requires both sides to understand what is happening: customers didn’t get what they thought they were buying or deserved. CSRs are on the edge of collapse after dealing with emotional customers all day long, yet they want to be helpful. At times they haven’t been given enough authority or information to handle complaints appropriately. But they aren’t in the business to make their customers miserable. The overwhelming majority want to do well with their customers. There is a mirroring of inherent desires here: the customer wants redress, and the service provider wants to help. The question is how to let each other see what they want to do, so the transaction can be completed with both getting what they want.

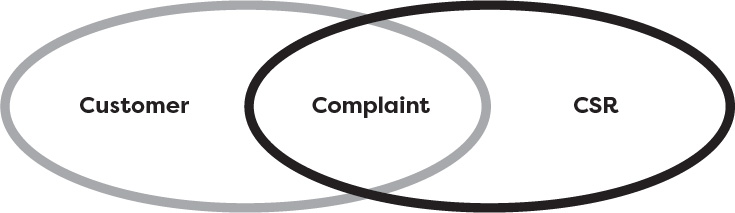

One of the most effective ways to “give a gift,” so to speak, is to look at the customer-CSR relationship as a Venn diagram. If you are not acquainted with Venn diagrams, they use circles to show relationships between at least two groups. In one circle, we have customers; in the second circle are the CSRs. The two circles intertwine in the middle, which is the connection between the two groups.

In the case of a complaint handler’s relationship with a customer, the customer is dissatisfied about something that happened or didn’t happen. It is the CSR’s task to handle the complaint. The customer is saying, “Please help me.” The CSR responds, “Thank you. Please help me help you.” That is the content of the intertwined relationship. The CSR doesn’t need to know everything about the customer’s life, just as the customer doesn’t need to know everything about the restrictions the CSR is placed under. They can both focus on meeting the customer’s needs, engaging each other with civility in that intertwined circle, which will probably result in a satisfactory outcome.

It can be constructive to explain emotions that are hard to control if you are the customer. This requires the customer to approach the CSR with a calm demeanor, moving into that interconnected portion of the Venn diagram. For example, “I’m sorry if I sound upset, but that’s because I am. I’m not upset with you. I’m upset with what happened/what I purchased/the delay I faced/how quickly this product broke down.” If you’ve had a difficult exchange with a service provider and you are now on your way to speak to a manager about what just happened, it’s a good idea to walk off your emotions before starting in on a second person. You’ll be heard better.

Clearly state your emotional reaction and the facts around why you are upset. Don’t exaggerate or threaten; be matter of fact. And then finish with saying, “And, I really need your help. I hope you can help me.” I can’t predict what will happen, but I do know presenting a less threatening emotional state will go a long way to getting help from the CSR on the telephone or standing in front of you.

Another way you, as a customer, can start is to say, “I think your company is better than this. I have been doing business with you for several years now, and I know you are better and have high-quality standards. Unfortunately, this [state the problem] happened, and I need your help.” As a customer, can you see the complaint handler as someone who wants to do his job well? This approach may not get you what you want as a customer, but at least you’ll both be operating from the connected part of the Venn diagram.

Think about the times when you were able to be helped or compensated as a customer. What was your behavior? Chances are you didn’t go ballistic and blame your complaint handler. When being accused, it’s hard for people not to get defensive; perhaps the CSRs have limited experience or haven’t read a book like this one and don’t know how to deal with upset customers. As a customer, you can help them do this. Show these hard-working people that you are nice. As stated earlier, most complaint handlers are unconsciously more likely to support the nice customer than someone yelling at them. And you won’t find it necessary to go back and apologize to the service provider because of how difficult you were! You’ll walk away from the complaint exchange feeling better about yourself.

Let’s look at complaints or feedback we receive from or give to our close friends, family, and loved ones, using the same principles and behaviors. Let’s also consider complaints we receive from a wide variety of people in our communities.

Handling Personal Complaints

Personal complaints come at us in huge numbers, especially if you open up an expanded idea about what feedback is. A driver in the middle lane may use his horn to give you the message, “Don’t change lanes. I can see you will hit me if you don’t get back in your own lane.” Notice how frequently the environment “complains” to us. We can take these notices as gifts to help us remain safe or remind us that we are about to do something socially unacceptable.

If you have ever watched the Olympics, especially the Winter Olympics, the intricacies of athletes’ movements require constant coaching if they have half a chance of winning one of the medals. You’ll notice that the coaches are close by their ice-skating athletes, whispering in their ears. You can see the coaches gesturing to let them know how to tilt their heads better, position their arms, twist their bodies, and dozens of other moves. In the ice-skating events, the coaches walk with the athletes, constantly giving them advice and motivation until the skaters step onto the ice. It’s unending, and those skaters have probably been working with their coach for years. It’s the same as a customer who gives businesses feedback that hopefully organizations will do something about. You could think of the coaches as delivering thousands of “complaints.” If skaters don’t accept that feedback and do something about it, they won’t improve either.

When somebody gives you feedback or a complaint, you have a choice to accept it, learn from it, and then be ready for the next piece of advice. The world is one big feedback cauldron, and hopefully we are constantly improving because we listen. It isn’t necessary to accept all feedback. But if we opened ourselves up to listen to feedback, then applied it judiciously, we could probably see constant dramatic improvement. On top of that, we might be a lot less irritated by this unending barrage of feedback.

The same thing happens in our close personal relationships. Feedback enables us to remain close to others if we don’t just turn ourselves off to what someone else is offering us. The Venn diagram is particularly useful when thinking through problematic personal relationships. Consider Gillian Laub, a remarkable storyteller and photographer of her family’s life. Laub lets her readers in on her family experience at a very personal level—warts and all.3 The “all” includes a family mess surrounded by a great deal of comfort and love.

The emphasis on Laub’s family conflict came during the political conflict in this century’s late teens and early twenties. Laub’s parents supported one party; its leader consumed them. Laub was an avid advocate of the opposition. Perhaps you have experienced this with parts of your family or some of your friends. Many families have separated as a result of their political choices.

As people worldwide have come to know in this period, it sometimes takes more than love to maintain a relationship in the face of radically different political views. Certain members of Laub’s family could not agree about their core political views. The pandemic and politics kept this close-knit family apart; the pain was devastating for all involved before they learned how to be around each other without fighting or relinquishing their political views.

Apply the Venn diagram to family conflict, and you can see how that model can help families like Laub’s. In one of the outer circles would be Laub and her husband. The other circle would house her parents, aunts, and other members who held opposing political views. Both sides needed to keep their political views in the two outside circles. But in the intertwined circle, the history, love, and care that the family shared existed. It required an effort on everyone’s part. Laub’s husband had to continually remind his photographer wife that maintaining her relationship with her family did not mean she validated their political beliefs.

It’s a great metaphor for any relationship where we aren’t in total unison. In the same way, we don’t have to become best friends with our customers to develop a mutually satisfactory business relationship. We don’t have to approve of their purchases or get turned off by the use of four-letter words. But we stand to lose a great deal if we allow our differences to break up personal relationships. You don’t have to pay these “coaches” a fee; they’ll do it for free. You have complete freedom of choice about whether to accept their advice. We also don’t have to reject someone in our business or social community because they coach us to better behavior.

The same thing happens when dealing with complaining customers or whoever else complains. Customers are not our family members; we didn’t grow up with them. But we know each other through shared cultures. Citizens of any country must share a somewhat cohesive community or break into tribal warfare. We can divide ourselves from our fellow citizens and family members or look for what binds us together. Empathy helps us find the ties that bind, and those ties keep families close.

Though this business application is the dominant thrust of this book, I hope you will read it and see how it applies to your personal life. When customers complain, we can disparage them because they negatively demanded help, or we can focus on the relationship we want to maintain. This approach to feedback is not so different from seeing another person as a partner in a relationship we want to keep because relationships are what make up families. It’s seeing feedback as a gift.

I have heard from people who attended my seminars or speeches weeks or months later. They explained they took my words to heart and opened up communication with family members, some of them even on their deathbeds. It was not easy, they say, but they have learned to accept whatever family members are doing that they disapproved of and put it in the outside circle. If they can’t tolerate something, they realize it’s not their total relationship with that person. When it comes to feedback, they don’t feel compelled to punish this person by stopping communication because of the way they offer feedback. Yes, they are still disappointed in many cases, but they have learned to say “Thank you” when being criticized or attacked. They realize this feedback or name-calling probably covers up some deeper emotions they will eventually release.

Would it be better if people who love each other never had to go through such agony? Of course. But once they are there, how can they focus on the shared love and not let their disagreements or destructive behaviors become the only thing present in the relationship? One way to begin is to thank people when they attack you with feedback. See if you can step away and come back to thank them for letting you know how they feel. Feel gratitude for the core of your relationship with that other person or family member. You don’t have to spend all your time with people who are difficult. But there’s probably a sliver of connection that is worth nurturing for family.

I hope you use these materials to help you in all your relationships. To see feedback as a gift, you must start with a gift mindset. It begins with gratitude—gratitude for the people who are in your life, appreciation that you have relationships with them, and gratitude that you have the power to keep those relationships in the face of conflict.

CORE MESSAGES

![]() Everybody has internal customers in any organization. Those internal customers have complaints as do paying customers. We need to learn how to handle internal complaints as well as we handle customer complaints.

Everybody has internal customers in any organization. Those internal customers have complaints as do paying customers. We need to learn how to handle internal complaints as well as we handle customer complaints.

![]() The Venn diagram identifies an overlapping space between people. It can help us deal with severe conflicts that possibly could split relationships apart.

The Venn diagram identifies an overlapping space between people. It can help us deal with severe conflicts that possibly could split relationships apart.

![]() Just because we don’t agree with other people’s viewpoints, we don’t have to validate their beliefs. We can focus on our connection points.

Just because we don’t agree with other people’s viewpoints, we don’t have to validate their beliefs. We can focus on our connection points.

DISCUSSION PROMPTS

![]() Do people in our organization use feedback from each other to develop themselves? How does this manifest itself? How can we encourage internal feedback?

Do people in our organization use feedback from each other to develop themselves? How does this manifest itself? How can we encourage internal feedback?

![]() How much energy is consumed by staff conflicts because people do not feel comfortable handling personal criticism?

How much energy is consumed by staff conflicts because people do not feel comfortable handling personal criticism?

![]() Does our organizational culture support people who apologize?

Does our organizational culture support people who apologize?

![]() Can we learn from accepting feedback in our personal lives so it positively influences how we work with complaining customers?

Can we learn from accepting feedback in our personal lives so it positively influences how we work with complaining customers?