Chapter II

Theory

Value

If a design has not changed in 18 years, the product is either excellent or management has failed to improve it.

Larry Zimmerman, American Value Specialist (1982)

First, I would like to introduce the concept of “value”; I will then investigate how value is managed. Value is a very subjective concept; it has different meanings for different people. A consumer will regard it as the “best buy,” a manufacturer will consider it the “lowest cost,” and a designer will view it as the “highest functionality.” Value does not stand alone: “In other words, value is a concept of time, people, subject, and circumstances, not just the subject alone” (Snodgrass and Kasi, 1986, 257). A very interesting concept was related by a customer in a survey and reported in Robert Tassinari’s book, Le rapport qualité/prix (1985): “Value is a combination of dream and concern. Dream is the idea one has of a product; concern is when you get the product and wonder if you’ve had your money’s worth.”

What is Value?

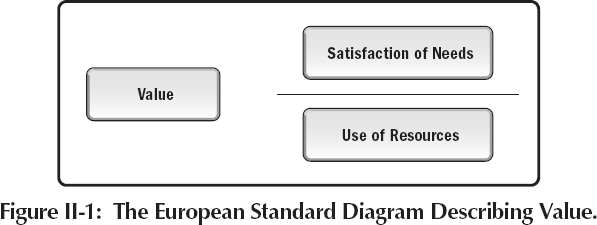

Since Miles’ time, value has evolved from a simple quality/cost ratio to a more customer-oriented notion. Customers can be both external and internal to the organization. The concept generally accepted by traditional value engineers was that value is a ratio of quality and cost; however, quality and cost can vary widely, according to the point of view, so most value managers now acknowledge that value is a ratio between the satisfaction of a need and the resources required to achieve it. Typically, value increases when the satisfaction of the customer’s need increases and/or the expenditure of resources diminishes. (Tassinari, 1985, 37).

Because needs cannot always be satisfied for lack of resources, customer value is a measure of relativity that consists of a balance between performance and resources. Performance is the capability to respond to the customer’s needs, and resources are the global overall resources (cost, time, equipment, human resources, capabilities and competences, etc.) needed to fulfill that need. Often, when setting up a project, there is a mismatch between the customers’ objectives and their capability to achieve them. The value system’s objective will be to find, or recreate, the balance between these two elements in order for the project to be a success. Every step of the way, the project team must aim for that balance between what is expected, what is needed, and what resources are available to produce it. In traditional project language, the value ratio can be expressed as the balance between scope and quality (performance) on one side and time and cost (resources) on the other.

In integrated value management, value is always customer (or sponsor)-oriented. An easy way to remember customer value is as follows:

What is Good Value?

The goal in value management is not merely to reduce costs but to balance outcome with resources. Traditionally, the greater the positive outcome (satisfaction of needs, quality, performance, benefits) and the smaller the resources used to achieve it, the greater the value.

The European Standard describes value as: “the relationship between the satisfaction of need and the resources used in achieving that satisfaction.” Although there are other definitions of value, this one is the most appropriate to the practice of value management. The European Standard (BSI, 2000) uses the representation shown in Figure II-1. In the standard appears the following note: “The symbol α signifies that the relationship between the satisfaction of need and the resources is only a representation. They must be traded off one against the other in order to obtain the most beneficial balance” (BSI, 2000).

SAVE International describes value as “a fair return or equivalent in goods, services, or money for something exchanged. Value is commonly represented by the relationship:

Value ![]() Function/Resources

Function/Resources

where function is measured by the performance requirements of the customer and resources are measured in materials, labor, price, time, etc. required to accomplish that function.” (SAVE, 2007. p.8)

These simple ratios work very well for value analyses on defined problems like construction projects, manufactured products, business systems, and processes or even services. It is more difficult to apply them to complex situations like organizational change or strategy development.

Although value is a subjective concept, it must be both measurable and achievable in order to be able to make the best decisions in projects, programs, portfolios, and organizations in general. Real value consists of achieved outcomes, not potential outcomes; sadly, many value studies still focus on potential outcomes and do not follow up to measure realized value.

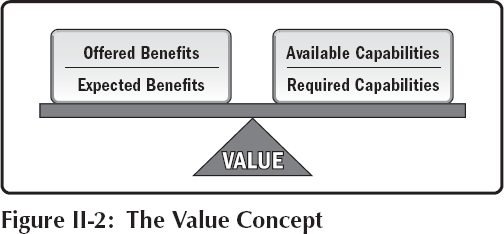

There are two dimensions to real value: the fit with expectations and the achievability of the solution. The expected outcome is defined by the different stakeholders that compose the sponsor group. A positive outcome can be defined as an increase on measured current performance or as a neutral or positive ratio between the offered outcome and the expected outcome. To assess achievability, capabilities should be balanced between what is available and what is required. If what is available is equal to or greater than what is required, the need can be fulfilled and the outcome achieved. This concept can be illustrated as follows.

The basic principle of this approach is that both the benefits variance (BV) and the Capability Variance (RV) should ideally be positive, or at least neutral, where:

BV = OB-EB ≥ 0 and RV = AC-RC ≥ 0

In order to obtain this measure, value management proposals (offered benefits) are assessed against their capability to achieve project’s objectives or program’s critical success factors (expected benefits), and available capability (resources, competence, financial, expertise…) will be assessed against requirements. If CV < 0, the project or solution cannot be achieved. The capability variance can be linked to a risk analysis. Following this evaluation, the value team will be expected to further the initial proposals in order to improve the value of the overall recommendation.

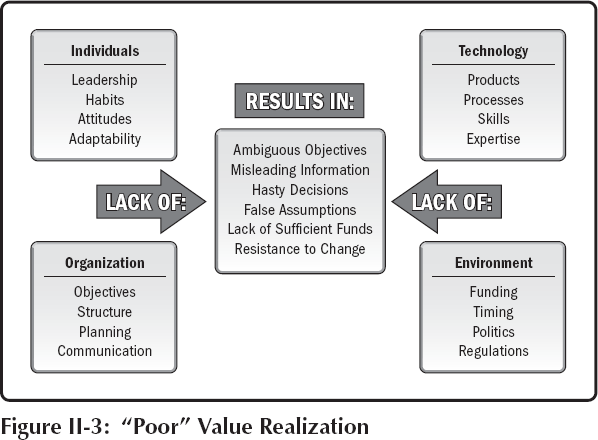

Failure to realize value is usually caused by a lack of an adequate level of performance in any number of areas:

Types of Values

Traditionally, the value management community has defined different types of value, and all of them must be pondered in a value study. Depending on the customer’s objectives, they will vary in importance, and more energy should be spent on optimizing those considered most important, while the less important after initial consideration, might not be taken into account.

Use Value—The amount of current resources expended to realize a finished product that performs as it was intended.

Esteem Value—The amount of current resources a user is willing to expend for functions attributable to pleasing rather than performing; e.g., prestige, appearance, and so on.

Exchange Value—The amount of current resources for which a product can be traded. It is also called worth, as the minimal equivalent value to be considered acceptable.

Cost Value—The amount of current resources expended to achieve a function measured in currency.

Function Value—The relationship of function worth to function cost.

Value Management

Rosabeth Moss-Kanter, who has conducted research and advised major corporations during what she terms “four major waves of competitive challenges” since the seventies (2006, 74) claims that successful innovation requires “flexible organizational structures, in which teams across functions or disciplines organize around solutions, [which] can facilitate good connections.” (2006, 82). Seeking balance in today’s constantly changing environment involves an openness of mind and an adaptation capacity that is sadly lacking in many traditional organizations and their managers and can be addressed with value management.

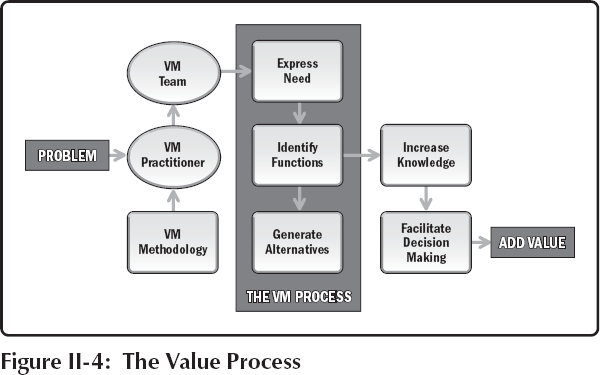

Value management—a term first used in 1974 by the U.S. General Services Administration—is a group decision making process that can be used to increase or achieve value in situations ranging from strategy development to technical problem solving. The combination of the following three key concepts underlies all value methodologies:

- The notion of function, which is the expression of needs in terms of purpose, independent from any solution

- The use of a cross-functional team, which enables a broad view and an increased knowledge of a situation

- A structured process, based on creative thinking; the alternate use of creativity and analysis, or lateral and vertical thinking (de Bono, 1970)

Value management consists of the integration of proven and structured decision making and problem-solving techniques known as value methodologies, which are combined with other management techniques. Value methodologies include all processes, tools and techniques derived from the work of Lawrence Miles.

Today there is a consensus to define VA and VE as specific methodologies aimed at improving or developing better products. A common distinction is to consider VA as the value-based analysis of existing products to improve them, and VE as the application of value techniques to develop new products. Officially, VE and VA are considered synonymous in both the SAVE International (2007, 2) Standard and in the European Standard (BSI, 2000). In their Standard, SAVE International uses the term value methodology to encompass both VE and VA and defines it as “a systematic process used by a multidisciplinary team to improve the value of a project through the analysis of its functions” (2007, 5). They add that: “A value methodology may be applied as a quick response study to address a problem or as an integral part of an overall organizational effort to stimulate innovation and improve performance characteristics.” (2007, 10) and define value management as: “The application of value methodology by an organization to achieve strategic value improvement.” (2000, 31)

They specifically include the concept of functions and function analysis (and their derivatives), the concept of cross-functional teamwork and the concept of a structured process based on creative thinking (alternative left/right brain use). There are a number of specific methodologies that have been developed worldwide on the basis of these, including, but not limited to: FAST Diagramming (U.S. and Canada), 40-hour workshop with job plan (U.S. and Canada), Split Workshops (UK), Function Tree (Europe and Canada), Function Cost (U.S. and Europe), Functional Performance Specification (France, French Canada, and Europe), Soft VM (Australia, U.K.) etc. The use of one methodology or another should not limit the value practitioner, whose first aim is to improve value within the limits of their intervention.

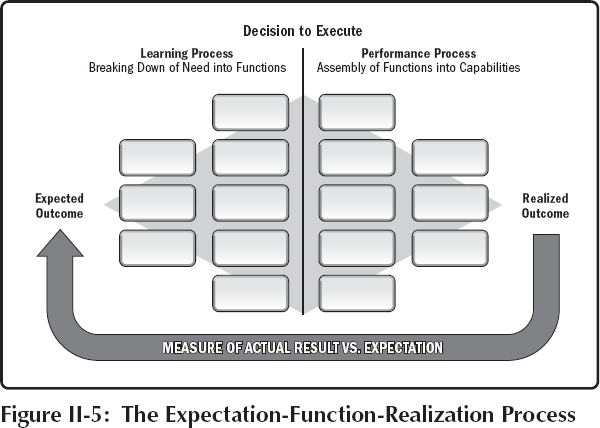

These value methodologies are implemented through a job plan using function analysis by a multidisciplinary team under the guidance of a knowledgeable value practitioner to seek out the best balance between expected performance and resources used to achieve them. Value management is associated with innovation and change; therefore, it is important for the value team to establish the strategic objectives to be achieved and to clearly state the business opportunity to be sought or threat to be addressed. Value management is, in fact, a learning process, the objective of which is to create a better understanding of a situation to find the best opportunities to address it. This can be contrasted with project management, a performing process the objective of which is to achieve stated goals with pre-agreed controlled resources.

In his book The Fifth Discipline (1990), Peter Senge lists eleven “laws” that govern the “learning organization.” Value methodologies directly address some of his concerns, such as:

- Today’s problems come from yesterday’s “solutions:” VM seeks to identify innovative solutions through its creative approach

- The easy way out usually leads back in: Value methodologies force participants to methodologically seek out solutions that address the “real” issues.

- The cure can be worse than the disease: VM balances the need to change with the value of doing so.

- Faster is slower: VM requires from participants that they commit the necessary sensemaking time to clearly state and understand the issues to be addressed before they start looking for solutions.

- Small changes can produce big results, but the areas of highest leverage are often the least obvious: Through its creative approach, VM requires participants to seek out alternatives that may not have seemed obvious and to analyze each of these alternatives in regards to the benefits it can produce and of its achievability.

- There is no blame: the whole VM process is based on the fact that participants can express their opinions and challenge existing situations without the fear of judgment.

The value study is graphically described in Figure II-2.

Functions

The functional approach is the basis of value management; function analysis is a fundamental step in any value study. We will see how a need, objective, target, or concept can be described in terms of its functions and what function means.

What is a Function?

A function is a concept by which value management practitioners describe a need in terms of its expected outcome rather than its expected solution. This concept enables the value team to generate creative alternatives that are not based on a technical solution, but rather on an expected outcome. Value management links the expected outcome to the realized outcome by breaking it down into its constituent functions. These are translated into deliverables that, once achieved, enable the outcome’s realization. If the process is consistent, the resulting outcome should correspond to the expectation (see Figure II-5).

An outcome describes an operational state created by the delivery of a new product, service, system, building, process, software, or any other project output. It describes a new capability for the organization using these outputs.

Desired outcomes should be defined by the customer or sponsor. Traditional value analysis and engineering spend time making a distinction between what is really needed and what could be considered as wants. This value judgment is typically exercised by the value team, not necessarily the customer or sponsor. Referring to need, Fallon (1977) states: “If excessive is generally bad, desirable is generally good; to ignore this fundamental distinction can lead, during a VA [value analysis] study, to dismiss the desirable, believing it excessive.” This brings us to reconsider the definition of customer need in a broader sense that includes desires as well as needs. John Bryant (1986) includes desires in the concept of value and describes customer value as follows: wants + needs/resources.

In order to establish customer-oriented value, one should understand that the need, expressed through its functions, is totally independent of technical solutions. Therefore, one can reasonably state that the customer’s expectations are usually quite stable, even if the technical solutions needed to fulfill them vary or evolve rapidly. If one bears in mind the satisfaction of the fundamental needs and manages to abstract the technical solutions, even clients that seemingly change their mind frequently are much easier to handle. This is typically what happens in program management or agile management, where the focus is on the ultimate benefit rather than specific technical solutions.

At the organizational level, functions can be associated with business benefits, as the function of an organization is to generate benefits (financial or others). The Standard for Program Management defines benefits as “an outcome of actions and behaviors that provide utility, value or a positive change to the intended recipient.” (Project Management Institute, 2013b, 34). The OGC (2010, 18) describes a function of a program as the delivery of one or more strands of portfolio strategy and the function of a project as the delivery of one or more requirements of the program (OGC). Gary Hamel, in his book Leading the Revolution, refers to benefits as: “a customer-derived definition of the basic needs and wants that are being satisfied. Benefits are what link the core strategy to the needs of the customer.” (2000, 87). Again, this demonstrates that focusing on only the bare essential is not sufficient, although identifying the essential can be a tool to compare different opportunities to a tolerable minimum performance.

Functions are usually described using an active verb and a measurable noun (e.g., chair = support weight). There are reasons for this method: abstraction from technical solutions, accuracy of the statement, broken down concept, “in extenso” description, clarified perception, easier consensus, and stimulated thought processes.

Functions have a few basic characteristics:

- Functions are use—or performance—oriented.

Chair is a solution, support weight is a performance or use. - A product can have several functions.

An office chair can support weight and allow movement. - Functions are totally independent of solutions.

Support weight can be accomplished with many different solutions: chair, stool, sofa, and so on. - Each function of the same product is independent.

Chair wheels should offer the best solution to support weight as well as the best solution to allow movement.

Types of Functions

There are different types of functions:

Primary or basic functions are those functions that justify the existence of the product and that guarantee its performance to expectations. Like critical success factors are those benefits that contribute directly to strategic objectives. These main functions can be divided into use functions (needs) and esteem functions (wants). For example, a chair must support weight, but it should also reflect status. Primary functions are customer/sponsor-oriented; dictated by the client’s needs and wants.

Supporting functions, also called secondary functions, are not secondary at all. They correspond to a complementary need that must be satisfied just as much as the basic need (e.g., a chair must not only support weight but also provide comfort). The supporting function is as important as the primary function, even if it is not essential to the product’s technical performance. In the same sense, financial benefits are essential to an organization’s success, but financial benefits alone do not make an organization valuable in the long-term.

Technical functions result from the design or the fabrication of the product (e.g., the “resist lateral effort” function of a chair). Customers often are not even aware of their existence, although they may be essential to the performance. Technical functions should never be considered in a function analysis that is not specifically directed at analyzing a design or an existing product.

Constraint functions are all the functions created by codes, regulations, standards, the site (in construction projects), technology limitations, market, and so on. These constraints usually are very specific; for example: “Endure 2,000 strikes of a fifty pound (23 kg) weight at an interval of ten seconds with less than 0.01 inches of deflection in the seat structure.” In customer terms, this translates to “exceed warranty.”

Unnecessary functions are all the functions that could be eliminated without affecting the product’s performance; for example, the “fact” that a chair must have four legs. Unnecessary functions usually are the result of honest wrong beliefs and assumptions or the perpetuation of obsolete requirements, but sometimes, they are “false constraints” that result from a lack of determination to find a solution to a problem; for example: “we absolutely need to follow this procedure” or “it would cost too much to replace our existing legacy systems.” These statements are a typical example of resistance to change that is often encountered in a value mandate. It is the role of the value management practitioners to recognize and challenge these false constraints.

The Team

Working independently, the resolution [of a problem] by one discipline becomes the problem of another.

J. J. Kaufman, American Value Specialist (1992)

The use of a multidisciplinary group is essential for creating completeness and consensus on proposed alternatives. Including participants from all levels and activity in a value study will ease communications and prevent distortion of facts.

Composition

Traditionally, value engineering studies have been conducted by means of a forty-hour workshop with a team of “experts” external to the project. This external expert approach is not appropriate to integrated value management, except under very specific conditions. In integrated value management the workshop should be essentially composed of the stakeholders, not external experts. Howard Ellegant, a well-known value engineering expert from the Chicago area, maintains that by using a peer review team on a value engineering workshop, you create an “adversarial relationship between the design team and the VE [value engineering] study team” (1993). He also states that “the very people who have to approve and implement the recommendations have no ownership of them and no stake in a positive outcome!” (1993).

Jerry Kaufman, author of a few books on value engineering, lists the following advantages of an “in-house” task value team (1992): easier implementation because of “buy in” of proposals; absence of adversarial confrontation with “outside” sources; development of professional respect; and compression of implementation time. He concludes that outside teams often are perceived as “venture capitalists” by internal resources. In general, the “expert consultant” approach is not recommended in today’s organizational environment where complexity and turbulence require a much more collaborative and participative approach.

As Peter Senge (1990) stated: “People don’t resist change, they resist being changed.” The more significant the change, the more this is true. Therefore, participants in the workshop should include representatives of all parties involved with the project concept, development, execution, and use because the needs and expectations of all the main stakeholders should be acknowledged and addressed and value proposals should be endorsed by every participant to be implemented successfully. A complete value management team includes key representatives of:

- Those whose needs the value study addresses, typically the change recipients and change agents;

- The sponsors, who will fund the effort;

- The performance team, that will deliver the value solution;

- The value team, which can include experts not available in the performance or recipients’ teams, but should not replace the performance team; and

- Any other stakeholders that are key to the setting of objectives or the realization of the initiative.

Additionally, the ability of the team to find innovative solutions will be greatly enhanced if the team is multidisciplinary, drawing on diverse expertise, both internally and externally. A well-balanced value team would be able to address all of the “ilities” of a project or product, namely producibility (constructibility), usability, reliability, maintainability, availability, operability, flexibility, social acceptability, and affordability (Ireland, 1991, II-2–5).

Tasks and Responsibilities

Each participant in the value team has responsibilities and tasks to accomplish.

Team Leader

The leader’s first task is to lead the value management process. He or she has the responsibility of preparing the team adequately by securing all the appropriate data and warrant that it complies with standard requirements. The leader also ensures that all members of the team have an adequate knowledge of value management and understand the job plan. The leader is also responsible for identifying the study’s objectives, ensuring adherence to the job plan, and following up on recommendations. The main qualities of a good VM leader are to be: responsible, open minded, humble, and able to synthesize. This person will exercise leadership on three levels: functional (procedure and organization), expertise (content and competence), and social (atmosphere and influence).

Workshop Participants

Ideally, the number of participants in a workshop should be limited; five to twelve is ideal for a traditional workshop. Larger workshops can be held in specific situations; in that case different facilitating techniques are used. Workshop results improve when participants are of equivalent hierarchical level, well-motivated, and endorse the value management principles.

Customer/Client

The customers must be convinced of the methodology, accept “opening their books” for the study, and agreeable to discussing their true needs and objectives. They must also be aware of the need to prioritize their needs and expectations in regard of available resources.

The Job Plan

The job plan is an organized approach to the conduct of a value study. The concept of a job plan is universal in its approach. Although it varies in terms of the number and name of its different steps, the job plan is essentially a decision making or problem-solving process. It has been successfully applied to manufacturing, systems processes, construction projects, health care facilities, software development and, in recent years, to strategy development. The job plan is the framework against which all value management actions are taken.

Why a Job Plan?

There are many good reasons to follow a job plan; following are eight of them:

- To obtain better results through a systematic approach.

- To use the allotted time in the most efficient way.

- To force participants to go beyond set standards.

- To emphasize performance over solutions, through function analysis.

- To identify high optimization potential areas.

- To allow everything to be questioned in a participative environment.

- To base recommendations and results on measurable data.

- To convince stakeholders to endorse the method.

Participants in a value study should be cautioned about the tendency to disregard the step-by-step approach of the job plan. A study that disregards the job plan would eventually catch the obvious value mismatches or find the evident solutions, but it would miss most of the expected results of a well-conducted study.

Examples of Job Plans

As stated above, there are a number of standardized value management job plans, depending on their country and/or organization; every value manager develops his or her own variation of the job plan. The job plan should be perceived as a foundation upon which every specific value study is developed, depending on the issue to be tackled.

My own experience demonstrates that the following basic steps of the value management process work well:

| (1) | Clarification of situation, including stakeholder analysis (information/preparation of team); |

| (2) | Elicitation of needs and agreement on objectives (sensemaking and function analysis); |

| (3) | Development of alternative solutions (creative ideation); |

| (4) | Prioritization/selection of options (feasibility analysis and options appraisal; and |

| (5) | Agreeing on measures of success and implementation of solutions (recommendation/follow-up). |

Some of these phases should be part of a workshop, while some are accomplished outside the workshop environment.

Historically, job plans have been standardized by value associations around the world the following examples are or were part of official standards, some of them having today fallen out of use.

Traditional: Five-Phase (Miles, 1972)

Value practitioners traditionally follow a standard five-phase job plan derived from Miles’ early-fifties seven-phase job plan that was designed to study existing manufactured products and try to improve them. Variations of this job plan exist, but they basically consist of subdividing the five phases into sub-phases or naming the phases differently. The standard job plan includes the following (Zimmerman and Hart, 1982):

- Information phase, during which all participants are presented the project and pertaining documents, and function analysis is performed.

- Creative phase, when ideas are generated in a brainstorming session.

- Judgment phase, at which time ideas are evaluated by the team according to their merit.

- Development phase, when ideas retained from phase three are developed into proposals.

- Recommendation phase, at which time proposals are presented to the client for implementation.

ASTM-SAVE International: Six-Phase (SAVE International, 2007)

A more integrated approach destined to design or reengineer products, processes, or projects is gaining acceptance. Consequently, more emphasis has been put on function analysis—which begins to appear between phases one and two as a phase in its own right—and on the follow-up of the proposal’s implementation. This evolution is reflected in the American Society for Testing Materials Standard’s job plan presented below (1995), as well as in the Department of Defense and the General Services Administration’s job plans (Zimmerman and Hart, 1982, 35) and its adoption by SAVE International in their Value Methodology Standard (2007):

- Information phase, during which all participants are presented the project, owner’s requirements, and pertinent data.

- Function Analysis phase, at which time function analysis is performed and cost/worth ratios are calculated.

- Creative phase, when ideas are generated through creative thinking.

- Evaluation phase; the ranking of ideas and evaluation of alternatives.

- Development phase, where proposed alternatives are developed, and life-cycle costs estimated.

- Presentation phase, when findings are summarized and presented to the client for implementation.

Association Française de Normalisation (AFNOR): Seven-Phase (1985)

In France, the Association Française de Normalisation (AFNOR) has standardized a seven-phase job plan that puts even more emphasis on “functional expression of need” and “function analysis” and integrates pre-workshop and post-workshop activities (1985, NF X 50–153). It is outlined as follows:

Preparation

- Orientation of activity

- Data gathering

Needs Analysis

- Function and cost analysis

Solutions Analysis

- Search of ideas and solution leads

- Study and evaluation of solutions

Results Implementation

- Anticipated results, presentation of proposals

- Follow-up of implementation

Her Majesty’s Treasury Central Unit on Procurement: Seven Phase (1996)

In the United Kingdom, Her Majesty’s Treasury recommends an integrated value management process, consisting of a series of reviews throughout the project. Each review is based on seven key steps:

Deutsche Industriell Normen Standard: Six Phase (1969)

German’s DIN standard relies on a six-step work schedule:

| (1) | Project preparation; |

| (2) | Analysis of object situation; |

| (3) | Description of ideal status; |

| (4) | Development of solution ideas; |

| (5) | Determination of solutions; and |

| (6) | Implementation of solutions. |

The process is iterative and guided by a constant reassessment of progress achieved toward project objectives.

Bureau of Indian Standards: Ten Phase (1987)

In India, the value engineering standard was established in 1986 and relies on a ten-step job plan:

The plan includes training and awareness in phases one and two.

Objectives of Each Phase

After many years of practice in both a North American and European environment, I have combined the American Society for Testing Materials’ job plan and European Value Management Standard plan to develop a job plan that has been proven effective in both strategic and tactical contexts. In the following section, I will detail this standardized plan. Specific techniques discussed in the section will be explained more in detail in further sections.

Preparation Phase

Before any value management study can begin, its objectives should be discussed with the client or sponsor. The way a value workshop is conducted may vary enormously depending on when and why it is undertaken. The objectives of each phase may also vary from one study to another. Thus, I will examine the basic objectives that should always be present because they lay the foundation for any value management workshop.

Sensemaking

The objective of the “Sensemaking phase” is to make sense of the situation to be studied: a learning process (Thiry, 2001). In the following, I have separated it into two sub-phases, definition and function analysis, to clarify their specific objectives.

Definition Phase

This phase consists of defining objectives and targets; it includes a presentation of the situation by the client or sponsor, the program or project manager (if assigned), and/or the business analysis team. Depending on the phase of the project during which the workshop takes place, the client or sponsor sets his or her requirements (needs and objectives), either of the program or project manager; the client or sponsor explains the program or project parameters (constraints and available resources); and the business analysis team presents the situation and context of the organization.

Any costs, actual or estimated are presented in elemental (categorized) format and modeled (Gantt chart, histogram, pie chart or other). Life-cycle costing should be included if appropriate and available.

The goal of this phase is to clearly identify the needs and objectives of the client or sponsor and make them unequivocal for every participant in the study; it is also to identify any potential optimization elements or areas to enable the team to focus its effort on the most rewarding areas of improvement.

Function Analysis Phase

Function analysis is extended to the degree required to better understand the situation. Depending on the level at which, or the phase during which, the workshop takes place, the function analysis will be more or less elaborate. Typically, an early strategic workshop will generate less functions of a higher level than a more technical later workshop.

At the strategic level, all options are still open, and function analysis becomes an integral part of the strategic planning and feasibility process. When conducted early in a program or project, it can be used effectively to determine the scope and setting of the program or project, and will create a baseline for change management. At the project level, the function analysis will drive the development work breakdown structure by defining the main objectives of the project from a functional point of view. The purpose is to create a “virtual” model of the program or project in terms of the benefits it should provide or the functions it should perform; it should not contain any technical solution.

This phase is usually conducted in a workshop environment, although parts of it can be conducted in sub-groups. The final set of functions must be agreed upon by the whole stakeholder group. At the end of the phase, the team will typically set measures (key performance indicators or KPIs) for each of the agreed basic functions.

Ideation Phase

This creativity and innovation seeking phase is always conducted in a workshop; it consists of using creative ideation techniques (brainstorming or other) to generate alternative solutions that will achieve the functions or benefits identified in the previous phase. In a strategic-level workshop, ideas will be more holistic and therefore the objective will be to look for more conceptual alternatives. In a technical workshop, hundreds of ideas can be generated in a few hours; the objective will be to generate a large number of specific alternatives.

Ideas are not discussed or judged during this phase; later phases will be devoted to thoughtful evaluation and careful development. The goal of this phase is to generate enough ideas to meet the client or sponsor requirements in a creative and innovative way.

Validation/Elaboration Phase

This phase consists of validating the ideas expressed in the previous phase and elaborating potential solutions to the situation or problem under study. Alternative ideas are discussed only to the degree required to make an informed decision. Impractical alternatives are eliminated, and experience is shared to identify advantages and disadvantages.

Ideas are then rated and ranked according to all relevant considerations, using one of several evaluation techniques. The target is to evaluate all ideas and alternatives in a timely manner and to prioritize and select those that offer the highest value potential. Chosen alternatives are then developed individually or in small groups by team members in consultation with others.

For each alternative, a value management proposal is written, including support to implementation, such as life-cycle cost estimates, contribution to benefits or functions, impact on other business initiatives, projects or project objectives, business or technical merit, risk evaluation, and other appropriate considerations.

The objective is to document each of the selected proposals in measurable terms with enough detail to convince the decision makers to adopt or reject them.

Recommendation and Decision Phase

The value team presents the decision makers with a prioritized list of proposals and summary recommendations. Typically, an oral presentation of these results is made to the key stakeholders for approval and a draft report of the proposals and summaries can be presented to the sponsor. The objective of the presentation is—for the key stakeholders—to adopt the proposals in view of their implementation. The report that follows should clearly establish the results of the study and confirm the meeting of the initial objectives.

Mastering

The concept of mastering comes from Peter Senge’s book The Fifth Discipline. In learning organizations, Senge (1990, 7) argues that mastering requires continually clarifying and deepening our personal vision, focusing our energies, and of seeing reality objectively. Mastering involves a continual learning mode. an ongoing process that requires discipline and a desire to grow.

Applied to value management, this concept involves the monitoring of value proposals to their conclusion through the realization of actual value for the stakeholders. It involves an agile process or realignment and readjustment to adapt to evolving circumstances as proposals are implemented and a continual reassessment of the context of the program or project to implement the changes that are required.

In integrated value management, the job plan is basically the same except that it is integrated into the program or project and extended over a longer period. Pre-workshop and post-workshop activities—definition and follow up—are given more emphasis since the value practitioner is involved earlier and supports implementation and value control. These two latter phases will be examined in more detail in Chapter IV.

Traditional VE Job Plan

For detailed methodology of the value engineering job plan, see also Dell’Isola (1988, 14, fig. 2-2) and Zimmerman and Hart (1982, chap. 3). Although their work is primarily directed towards the traditional forty-hour workshop, it is beneficial in specific value engineering mandates.

Where and When to Use Value Management

Every time a business initiative is being planned, or an existing process or product requires improvement, the application of value management should be considered. More specifically, when a product does not sell or generates complaints from customers, or when new markets need to be explored, value management is profitable. When a project is not evolving according to plan, or when one of the project parameters or objectives are not achieved, value management techniques are applied to bring it back on track.

Ideally, value management should be implemented in the very early stages of development when a commitment has not yet been made. This enables value to be used to its greatest potential: to clearly identify the expected performance and functions of the business initiative, product, or project. If this is not possible, it is still feasible to use value management very effectively at any stage of the planning or development phases.

Any size initiative is suitable to a value study; only the extent of the study and the size of the team will vary. As long as the value, function, multidisciplinary team, and job plan concepts are present, it is value management.