Chapter 3. Defining and Documenting a Process

What is the Objective of This Chapter?

In order to improve a process you must define it, then you must document it and, then you must analyze it to improve the process.

The objective of this chapter is to teach you how to:

1. Define a process by: looking at who owns, and is responsible for, the process by understanding the boundaries of the process, and by understanding the objectives and metrics of the process used to measure its success.

2. Document a process by: understanding flowcharts and how to use them to document a process.

3. Analyze a process by: understanding how to analyze a flowchart to begin improving a process.

A Story to Illustrate the Importance of Defining and Documenting a Process

Defining and documenting a process is a critical step toward improvement and/or innovation of a process. The following example demonstrates this point. In a study in a billing office at a hospital laundry an analyst began to diagram the flow of paperwork using a flowchart. While walking the green copy of an invoice through each step of its life cycle, he came upon an administrative assistant transcribing information from the green invoice copy into large black loose-leaf books. The analyst asked, “What are you doing?”, so that he could record it on his flow diagram. She responded, “I’m recording the numbers from the green papers into the black books.” He asked, “What are the black books?” She said, “I don’t know.” He asked, “What are the green papers?” She said, “I have no idea.” He asked, “Who looks at the black books?” She said, “Well, Mr. Johnson used to look at the books, but he died 5 years ago.” The analyst asked: “Who has looked at them for the last 5 years?” She said: “Nobody.” He asked, “How long have you been doing this job?” She said, “Seven and one half years.” He asked, “What percentage of your time do you spend working on the black books?” She said, “100 percent.”

Next, the analyst did two things. First, he examined the black books. From examining the black books he realized that they were inventory registers. Every day all laundry pulled from central supply was recorded on the green papers (invoices) by item onto the appropriate page in the black books. At the end of each month, page totals were calculated, yielding monthly used laundry inventory by item. Second, he asked the administrative assistant how long ago the person who hired and trained her had left the hospital: “Five years ago.” At this point, the consultant realized he had solved a problem the hospital did not know it had. Nobody was looking at the books because nobody knew what the administrative assistant was doing. The current manager assumed the administrative assistant was doing something important. Surprisingly, the current manager had computerized the sales registered as soon as he came on the job; five years ago! So, the administrative assistant had been doing a redundant job for five years. Nobody had bothered to document the process. The administrative assistant was a wheel that didn’t squeak; so why study her? As an epilogue, the administrative assistant was reassigned to other needed duties because she was a good employee.

This problem is an example of a failure to define and document a process to make sure that it is logical, complete, and efficient.

Fundementals of Defining a Process

Who owns the process? Who is responsible for the improvement of the process?

Every process must have an owner; that is, an individual who is responsible for the process (Gitlow and Levine, 2004). Process owners can be identified because they can change the flowchart of a process using only their signature. Process owners may have responsibilities extending beyond their departments, called cross-functional responsibilities; their positions must be high enough in the organization to influence the resources necessary to take action on a cross-functional process. In such cases, a process owner is the focal point for the process, but each function of the process is controlled by the line management within that function. The process owner will require representation from each function; these representatives are assigned by the line managers. They provide functional expertise to the process owner and are the promoters of change within their functions. A process owner is the coach and counsel of her process in an organization.

The identification and participation of a process owner is a critical first step in defining a process. It is usually a waste of time to be involved in defining and documenting a process, as part of process improvement activities, without the complete commitment of the process owner.

What are the boundaries of the process?

Next, boundaries must be established for processes; in other words, before a flowchart of the process can be created, the process owner must help you identify where the process starts and stops (Gitlow and Levine, 2004). These boundaries make it easier to establish process ownership and highlight the process’s key interfaces with other (customer/vendor) processes. Process interfaces frequently are the source of process problems, which result from a failure to understand downstream requirements; they can cause turf wars. Process interfaces must be carefully managed to prevent communication problems. Construction of operational definitions for critical process characteristics that are agreed upon by process owners on both sides of a process boundary will go a long way toward eliminating process interface problems. Operational definitions will be discussed later in this book.

A Story About Process Boundaries

One of the authors was consulting at a paper mill, and he noticed that the entire mill was surrounded by a nine foot tall chain link fence. He realized that since a paper mill is a very dangerous place, even potential intruders have to be protected.

As was his custom, he started his tour from the beginning of the process, in this case the wood procurement area. This is the where trees enter the mill on flat bed trucks and are cut into 40 foot lengths by large saws. Everyone the consultant met was very nice and helpful.

The next part of the process was the wood yard. This is the area where the 40 foot logs are turned into wood chips for making paper. He noticed that there was a chain link fence between these two areas. That was to prevent truckers from wandering into the wood yard. However, the chain link fence also had a door that was pad locked, and on top of the chain link fence was concertina barbwire, coils of wire with razor blades attached. It would slice to pieces anyone trying to get over it.

The consultant wondered why the wood procurement area would be more concerned about the wood yard employees than they would be about outsiders. The wood procurement folks opened the padlocked door between the two areas and let the consultant enter. He thought he was about to be attacked by wild lions. In the distance he saw a man walking toward him, and as he got close, the consultant stuck out his hand to shake the wood yard manager’s hand.

The wood yard manager did not reciprocate and called the consultant an ethnic slur that was relevant only to a very small area in Europe that his ancestors were from. How this man would have known this term was a mystery to the consultant. Apparently he was a savant of bigotry.

Now the consultant knew why there was concertina wire between the two mill areas; it was a statement of mutual hatred. When the consultant asked the wood yard manager why there was so much hatred between the two mill areas, he responded: “They are morons! They cut the logs into 40 foot lengths and we need 20 foot lengths for our equipment to operate at its best.” When the consultant asked why they didn’t know to cut the logs into 20 foot lengths the manager said, “They should know.”

At that point, the consultant realized that the wood procurement area was so put off by the manager of the wood yard that they had no communication whatsoever, even to the extent on which size saws to purchase. This is a classic example of a very clear dysfunctional process boundary. Most disagreements occur at process boundaries.

What are the process’s objectives? What measurements are being taken on the process with respect to its objectives?

A key responsibility of a process owner is to clearly state the objectives of the process and indicators that are consistent with organizational objectives (Gitlow and Levine, 2004). An example of an organizational objective is: “Provide our customers with higher-quality products/services at an attractive price that will meet their needs.” Each process owner can find meaning and a starting point in the adaptation of this organizational objective to his process’s objectives. For example, a process owner in the Purchasing Department of a health system could translate the preceding organizational objective into the following subset of objectives and metrics:

Objective: Decrease the number of days from purchase request to item/service delivery.

Metric: Number of days from purchase request to item/service delivery by delivery overall, and by type of item purchased, by purchase.

Objective: Increase ease of filling out purchasing forms.

Metric: Number of questions received about how to fill out forms by form by month.

Objective: Increase employee satisfaction with purchased material

Metric: Number of employee complaints about purchased material by month.

Objective: Continuously train and develop Purchasing personnel with respect to job requirements.

Metric: Number of errors per purchase order by purchase order.

Metric: Number of minutes to complete a purchase order by purchase order.

Whatever the objectives of a process are, all involved persons must understand them, and devote their efforts toward those objectives. A major benefit of clearly stating the objectives of a process is that everybody works toward the same aim/mission.

Fundamentals of Documenting a Process

Now that we have identified the process owner, know where the process starts and stops, and understand the objectives/metrics to measure success, it is time for us to document the process. Documenting a process requires input from all of the stakeholders of the process, as they may have different points of view on the flow of the process.

How do we document the flow of a process?

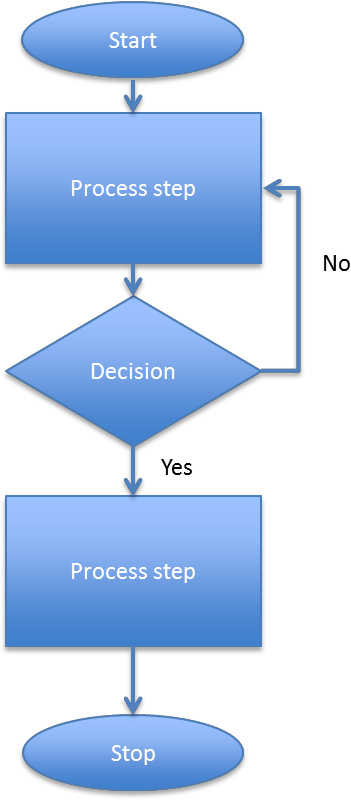

To document a process we use a flowchart, which is a pictorial summary of the steps, flows, and decisions that comprise a process (Fitzgerald and Fitzgerald, 1973; Silver and Silver, 1976). Figure 3.1 below shows a simple generic flowchart.

Figure 3.1. A Simple Generic Flowchart

Why and when do we use a flowchart to document a process?

Documenting a process using a flowchart, as opposed to using written or verbal descriptions has several advantages:

• A flowchart makes it easier for people who are unfamiliar with a process to understand it.

• A flowchart allows for employees to visualize what actually happens in a process, as opposed to what is supposed to happen.

• A flowchart functions as a communications tool. It provides an easy way to convey ideas between engineers, managers, hourly personnel, vendors, and others in the interdependent system of stakeholders for the organization. It is a concrete, visual way of representing a complex system.

• A flowchart functions as a planning tool. Designers of processes are greatly aided by flowcharts. They enable a visualization of the elements of new or modified processes and their interactions.

• A flowchart removes unnecessary details and breaks down the system so designers and others get a clear, unencumbered look at what they’re creating.

• A flowchart defines roles. It demonstrates the functions of personnel, workstations, and sub-processes in a system. It also shows the personnel, operations, and locations involved in the process.

• Flowcharts can be used in the training of new and current employees.

• A flowchart helps you understand what data needs to be collected when trying to measure and improve a process.

• A flowchart can also be used to be compliant with regulatory agencies, i.e., JCAHO (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations )

• A flowchart can be used to compare the current state of the process (how the process is), the desired state of the process (how the process should be with standardization), and the future state of the process (how the process could be with improvement).

• And last, but not least, a flowchart helps to identify the weak points in a process; that is, he points in the process that are causing problems for the stakeholders of the process.

Flowcharts can be applied in any type of process to aid in defining and documenting it, and ultimately to improve and innovate the process.

What are the different types of flowcharts and when do we use each?

There are two types of flowcharts we will cover in this chapter that are used in process improvement activities: process flowcharts and deployment flowcharts. Each type of flowchart has different features that will be discussed below.

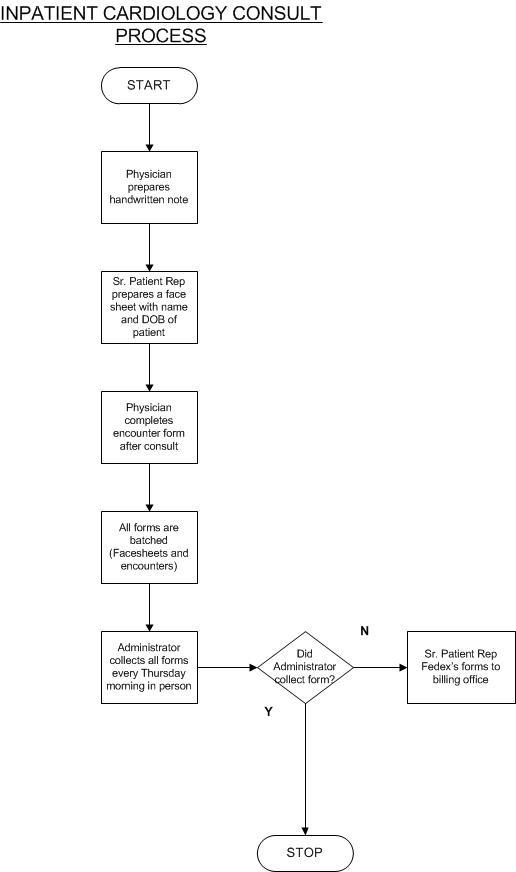

Process flowchart:

What is it?

• A flowchart which lays out process steps and decision points in a downward direction from the starting point to the stopping point of the process.

When to use it?

• When you want to depict a process at a high level or when you want to drill down into a detailed portion of a process.

What does it look like?

• An example of a process flowchart for a typical inpatient cardiology consult process is shown below in Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2. Process Flowchart Example

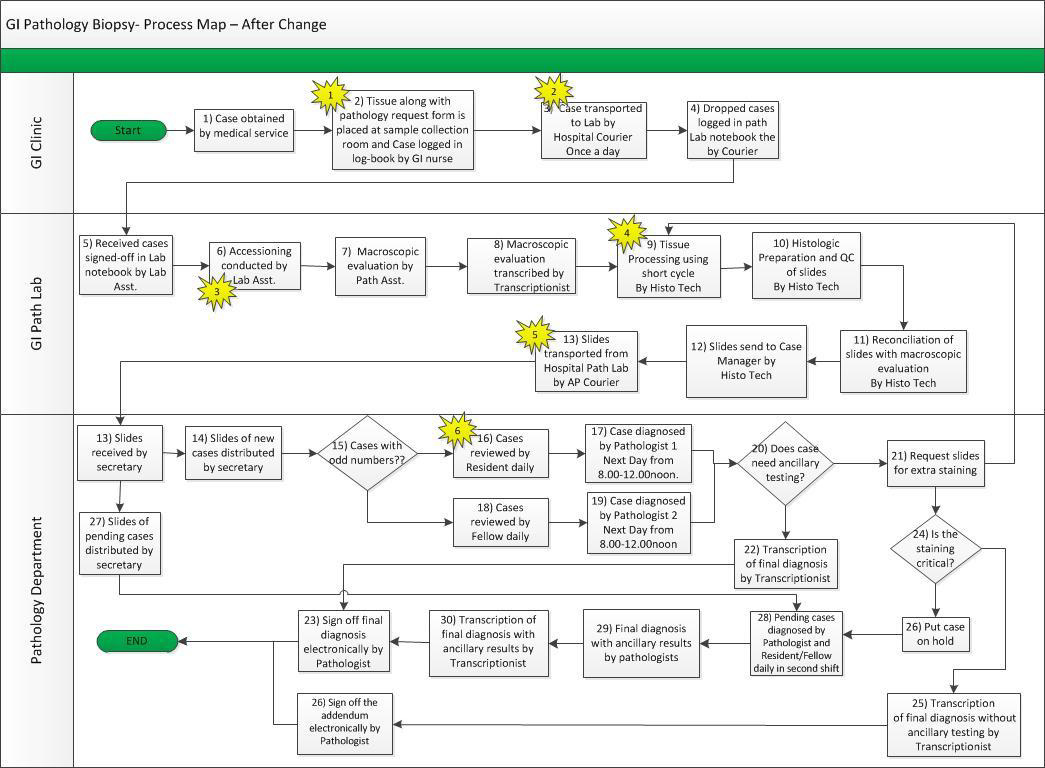

Deployment flowchart (also known as cross functional or swim lane flowcharts)

What is it?

• A flowchart which is organized into ‘lanes’ which show processes that involve various department, people, stages or other categories.

When to use it?

• When you want to show who is responsible for different parts of a process as well as tracking the number and location of handoffs within the process.

What does it look like?

• An example of a deployment flowchart for a surgical biopsy sign out process is shown below in Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3. Deployment Flowchart Example

The starbursts in figure 3.3 show areas of the process that are suspected of causing problems in the process’ outputs. The starbursts can come from process experts, reviews of the available literature, benchmarking with similar processes in other organizations, or many other possible sources. All the possible sources of the star bursts will be discussed later in this book.

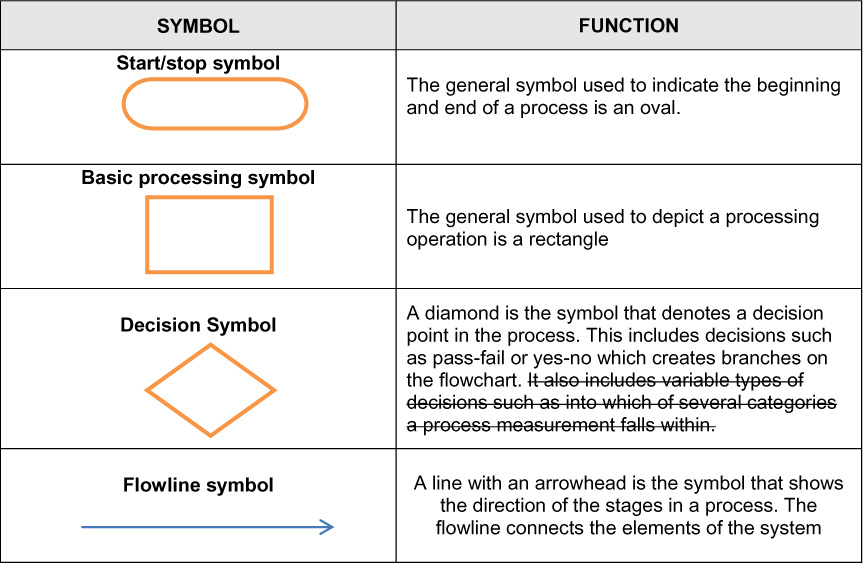

What method do we use to create flowcharts?

The American National Standards Institute, Inc. (ANSI) has developed a standard set of flowchart symbols that are used for defining and documenting a process, some of which are shown in Table 3.1. The shape of the symbol and the information written within the symbol provide information about that particular step or decision in a process.

Table 3.1. American National Standards Institute Apprved Standard Flowchart Symbols

• Flowcharts provide a common language for the stakeholders of a process to discuss the process, for example, where it begins and ends, who is responsible for each step in the process, how does the process flow, how should the process flow, too name a few benefits of flowcharts...

• Flowcharts help managers see that the responsibility for the outputs of the process are their responsibility, as opposed to the employees that work in the process, because they designed and manager the process.

• Flowcharts provide stakeholders a tool to walk the process from front to back (process owner’s point of view) and back to front (customer’s point of view).

• Flowcharts provide an opportunity for the stakeholders of a process to identify the problematic steps in the process (starbursts).

Fundamentals of Analyzing a Process

How do we analyze flowcharts?

Process improvers can use a flowchart to change a process by paying attention to the following five points:

1. Process improvers find the steps of the process that are weak (for example, parts of the process that generate a high defect rate).

2. Process improvers improve the steps of the process that are within the process owner’s control; that is, the steps of the process that can be changed without higher approval from the process owner.

3. Process improvers isolate the elements in the process that affect customers.

4. Process improvers find solutions that don’t require additional resources.

5. Process improvers don’t have to deal with political issues.

If these 5 conditions exist simultaneously, an excellent opportunity to constructively modify a process has been found. Again, process improvements have a greater chance of success if they are either non-political or have the appropriate political support, and either do not require capital investment or have the necessary financial resources.

Other questions that the process improver can ask are:

• Why are steps done? How else could they be done?

• Is each step necessary?

• Are they value added and necessary? Are they repetitive?

• Would a customer pay for this step specifically? Would they notice if it’s gone?

• Is it necessary for regulatory compliance?

• Does the step cause waste or delay?

• Does the step create rework?

• Could the step be done in a more efficient and less costly way?

• Is the step happening at the right time? (sequence)

• Could steps be done in parallel with another step to cut cycle time?

• Are the right people doing the right thing?

• Could steps be automated?

• Does the process contain proper feedback loops?

• Are roles and responsibilities for the process clear and well documented?

• Are there obvious bottlenecks, delays, waste or capacity issues that can be identified and removed?

• What is the impact of the process on stakeholders?

Things to remember when creating and analyzing flowcharts

• Work with people who really know and live the process such as frontline employees. Managers may think they know how it works, or how it is supposed to work, but those on the front lines can tell you how it really works.

• Make people understand you are only there to help. The last thing you want anyone to think is that their job may be in jeopardy if their process gets improved so much that it is no longer necessary. You are there to help them do their jobs better, not to eliminate them. Explain they have employment security, not job security. Job security leads to redundancy and unnecessary work; for example, if a unionized electrician knocks a water pipe loose, s/he can’t fix it due to union rules. A plumber must be called in to fix it and much damage could result in the factory in the interim. However, if employees are guaranteed employment and wage security, then they are more open to cross training and the above scenario would not happen.

• Start high level to identify major components of the process, then drill down

• Keep asking questions, and question everything

• Involve enough people so you get a complete understanding of the process

• Validate and verify with key stakeholders to make sure the process is understood

• Keep the flowchart as simple and understandable as possible so it anyone can follow it

• Walk the process from to front to back (process owner’s point of view) and from back to front (customer’s point of view).

• Focus on the needs of the customer

• Only improve processes with data and facts

Takeaways from This Chapter

• There are four steps used to define a process:

• Identify the process

• Identify the process owner

• Identify where a process starts and where it ends

• Identify the objectives and metrics to measure the success of a process

• Flowcharts are used to document a process

• The two main flowcharts used in process improvement activities are process flowcharts and deployment flowcharts

• Practice, practice and more practice!

References

W. Edwards Deming (1982), Quality, Productivity, and Competitive Position (Cambridge, Mass.: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study).

W. Edwards Deming (1986), Out of the Crisis (Cambridge, Mass.: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study).

J. M. Fitzgerald and A. F. Fitzgerald (1973), Fundamentals of Systems Analysis (New York: John Wiley and Sons).

Gitlow,H., Oppenheim,A., Oppenheim,R., and Levine,D., Quality Management: Tools and Methods for Improvement, 3rd ed., (New York: McGraw-Hill-Irwin, 2005)

Gitlow, H. and Levine, D. (2004), Six Sigma for Green Belts and Champions: Foundations, DMAIC, Tools and Methods, Cases and Certification, Prentice-Hall Publishers (Saddle River, NJ).

G. A. Silver and J. B. Silver (1976), Introduction to Systems Analysis, (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall).