13 FREEDOM OF INFORMATION

Victoria Hordern

Any private computer company doing business with the public sector must recognise the influence of the Freedom of Information Act 2000. Freedom of information is about the public’s right to know how public money is spent and how public sector decisions are made. This chapter aims to give the reader a working knowledge of the rules under the law, what exemptions exist to withhold information and how a private computer company should prepare for a request for disclosure of its commercial or sensitive information.

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA or the Act) was part of the newly elected Labour Government’s drive in 1997 to shake up the British constitutional system. All public authorities are required to provide people who exercise their rights under the Act (’requestors’) with information that the public authority holds regardless of where it came from or who owns it. The changes were part of moving from a ‘need to know’ to ‘right to know’ culture. In practice, the right to environmental information has been around for a lot longer (where a requestor asks for disclosure of environmental information the Environmental Information Regulations 2004 apply rather than FOIA). Furthermore it is likely that the reach of the Act will be extended so that the access to information regime will become even more important.

As a consequence, all private companies dealing with the public sector need to consider carefully the information they provide to public authorities. The advent of Public Private Partnerships (PPP) and Private Finance Initiatives (PFI) in the 1990s has led considerably more private companies to provide services both to and on behalf of local and central government. When contracting on this basis, private companies inevitably provide considerable amounts of information to a public authority about their business proposal. Disclosure of this information under FOIA can present a commercial risk to private companies and put them at a disadvantage with competitors. Furthermore, the FOIA itself does not provide a private company with any sanctions to stop disclosure. Consequently a private company is relatively powerless when facing a disclosure by a public authority of its confidential information and is forced to rely on contractual or common law remedies. On a practical level, private companies need to focus on maintaining a good working relationship with the public authority and encouraging the public authority to involve them when a request relates to information about the company. From a legal perspective, the private company should ensure that there is a clear FOIA clause in any contract or non-disclosure agreement.

Of course there is nothing to stop a private company making a FOIA request itself to a public authority in order to understand certain issues within the public authority or to obtain information about competitors held by the public authority. However, be aware that making requests in your own name could influence the public authority’s attitude towards you!

TRANSPARENCY AGENDA

The incoming 2010 Coalition Government has set out plans to open up government data that includes the commitment to publish online all new central government IT contracts with a value of more than £10,000. Central government in this context includes agents and agencies of central government, all non-departmental public bodies, the National Health Service (NHS) and trading funds. Guidance produced by the Office of Government Commerce (OGC) indicates that redactions from IT contracts may be made by a public authority before publication in line with available exemptions under the FOIA. Otherwise, the contract should be published in full. In this context, suppliers should be given the opportunity to identify which pieces of information they regard as exempt under FOIA and why. However, a public authority is not obliged to withhold information by relying on exemptions cited by the supplier. The Transparency Agenda marks a shift towards proactive publication, and suppliers of IT services to the public sector should therefore assume in most instances that information contained in the contract they sign will be published.

PUBLIC AUTHORITIES

One of the first questions to consider when thinking about FOIA is to check to see whether the organisation you are dealing with is a public authority under FOIA. Sometimes this can be straightforward since you can check on the organisation’s website to see whether they indicate what their status is under FOIA, but it may not always be clear. Most public authorities are listed by name under Schedule 1 Part I of the Act. However, there are other rules that catch organisations that are not listed but may be publicly owned companies or otherwise designated by the Secretary of State as a public authority. In reality, in the last few years, the Secretary of State has proposed designating very few new organisations as public authorities: the Association of Chief Police Officers and the Universities and Colleges Application Services are recent examples. At the time of writing there is no one comprehensive list of public authorities that are caught by FOIA.

A PUBLIC AUTHORITY’S OBLIGATIONS

As well as providing a publication scheme (which is typically accessible through the public authority’s website and sets out what information is routinely made available), a public authority must comply with two obligations under FOIA in response to a request for information. It must:

- confirm or deny whether it holds the information; and

- make such information available.

The public authority is required to respond to the requestor within 20 working days of receiving a request either providing the information requested or setting out the specific exemptions and an explanation as to why such information cannot be disclosed. When exemptions require an examination of what is called the public interest test (defined below), the public authority may take a further 20 working days (i.e. 40 working days in total) to consider the public interest arguments if it so requires. However, the public authority must still respond after the initial 20 working days to notify the requestor of the exemption it seeks to rely on and that it needs longer time to consider the public interest test. A public authority cannot indefinitely delay responding fully to a request.

In certain cases the request may not be formulated clearly, may be too general or ask for access to a lot of information. The public authority cannot simply refuse a request on those grounds. It is under a duty to provide advice and assistance to requestors, which may require seeking clarification from the requestor as to the actual information they are seeking, helping the requestor focus their request and providing information that it is able to locate within a specific period of time. However, there are limits to the amount of effort the public authority is required to expend in order to determine whether it holds information (discussed below).

PROVIDING INFORMATION TO THE PUBLIC AUTHORITY

Where private company information is subject to disclosure

Since the Act catches all information held by a public authority, this will include all information supplied to a public authority by a private company in the context of discussions, contract negotiations and contract delivery. This means that the tender document prepared by the private company setting out its business proposal and references from previous customers will be caught. Likewise, at contract negotiation stage, the technical specification, service level agreement, IT and security policies, methodologies and algorithms that underline the particular solution (once provided to the public authority) are caught together with the payment schedule that sets out the unit costs for particular products and services that the private company will provide to the public authority. Given that FOIA will apply to all information held by a public authority you should consider whether you need to provide to the public authority any information beyond that which is strictly necessary to include in the contract as part of documenting the legal agreement between the parties.

Where the private company is required contractually to help a public authority locate the information that is requested under FOIA

Where a private company provides a service on behalf of a public authority, the company must recognise that the information it holds on behalf of the public authority is subject to FOIA. This rule ensures that public authorities cannot avoid the effects of FOIA by procuring private companies to hold information for them. In most contracts, the public authority will seek to impose an obligation on the private company to assist the public authority in complying with any FOIA request (or indeed request under the Data Protection Act 1998) to disclose information. When faced with this obligation, the company should consider how it would go about locating and providing the information. For instance, will the IT system be designed to run searches that will be able to easily locate information? Additionally, the company should consider whether it wishes to provide this assistance as part of the overall services to the public authority or whether it wishes to seek a reimbursement of its costs for this exercise. It is better for discussions on this point to occur at contract negotiation stage rather than at the time that a public authority is pressing the company for assistance so that the public authority can comply with the 20 working day limit.

THE REQUEST PROCESS

It is important to bear in mind that there is no requirement on the public authority under the FOIA to involve the private company when the private company’s information is requested. A timeline of a request is set out below.

Request received by the public authority

Once a request is received, the public authority must assess its scope and decide whether it understands what information is being sought. The public authority must treat the request as applicant-blind and motive-blind so it cannot make a decision not to disclose information to a particular requestor because it suspects their motive. The only exceptions to this rule are where the request is vexatious or compliance would exceed the appropriate limit (see below).

The public authority must then consider whether it holds the information in question and should seek to locate it within its records and files.

Once the information has been located, the public authority should consider whether the information should be disclosed or whether it can rely on an exemption to withhold the information. Even if an exemption is available, the public authority is not required to rely on it. It is at this stage that a public authority should seek to involve a third party, such as a private company, if the information in issue relates to that third party.

Once the public authority has reached a decision about whether to withhold all or part of the information or whether to disclose all, it will respond to the requestor. Some public authorities maintain a disclosure log on their website with access to all the responses they have sent to requests.

After the response is sent to the requestor, it will only go further if the requestor seeks an internal review of the public authority’s decision.

If the requestor disputes the public authority’s decision, the public authority must conduct an internal review that must be carried out by a suitably senior and independent person within the public authority.

The internal review must take place relatively quickly and the requestor be provided with the results of the review.

Appeal to the Information Commissioner’s Office

If the requestor remains unsatisfied with the way that their request has been handled, they can then take the matter to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). The ICO hears all appeals from a FOIA request at an initial stage but private companies cannot directly present their arguments to the ICO. In the early days of FOIA, the ICO was faced with a huge backlog of appeals from FOIA requests that meant that the process took months or even years. More recently, the ICO has improved the efficiency of the appeals process although it can still take some time.

The ICO considers the complaint from the requestor, contacts the public authority to ask for the relevant information that is the subject of the request for it to assess and then makes a decision, which is published on the ICO website. The decision sets out whether the public authority was correct to rely on an exemption to withhold information or whether the ICO considers the public authority was wrong and should now disclose the information.

Appeal to the Information Tribunals

Either the requestor or the public authority can challenge the ICO’s decision by appealing to the relevant Tribunal. New rules that came into force in 2010 mean that appeals from the ICO’s decision are either heard at First-tier Tribunal (Information Rights) level or at Upper Tribunal level.

If the matter is significantly serious the appeal goes to the Upper Tribunal (e.g. appeals against national security certificates are automatically sent to the Upper Tribunal). Otherwise most matters are dealt with by the First-tier Tribunal. It is at the Tribunal stage that third parties (such as private companies) can be joined to the proceedings in order to represent their interests before the Tribunal. For instance, T-mobile joined as a third party when an appeal was brought by Ofcom against an ICO decision that required disclosure of information that impacted on the mobile phone industry.

The Tribunal considers the arguments and comes to a decision, which is published on the Tribunal’s website. Further appeals to the appropriate court are only permitted if there is a dispute on a point of law.

WITHHOLDING INFORMATION

It is important that private companies are aware of the circumstances in which a public authority can withhold information under an exemption. FOIA provides two types of exemption: absolute and qualified exemptions. Absolute exemptions do not require any consideration of the public interest test. However, all qualified exemptions require the public authority not only to consider whether the information is exempt but also to determine whether in all the circumstances of the case the public interest in maintaining the exemption outweighs the public interest in disclosure (the public interest test). Since the default position under FOIA is that the public interest always favours disclosure, in order to rely on a qualified exemption, the arguments in favour of maintaining the exemption (i.e. withholding the information) must always outweigh the arguments in favour of disclosure.

The public authority must consider public interest arguments both in favour of disclosure (e.g. holding public authorities accountable for the spending of public money, helping the public understand decisions taken etc.), and in favour of withholding (e.g. timing of the request may be critical, the public authority’s ability to procure services from the private sector would be damaged etc.). It is important to note that what is ‘of interest to the public’ is not the same thing as what the public interest test recognises as ‘in the interests of the public’. Furthermore, the public interest test is concerned with the public as a whole not with the interests of the individual requestor.

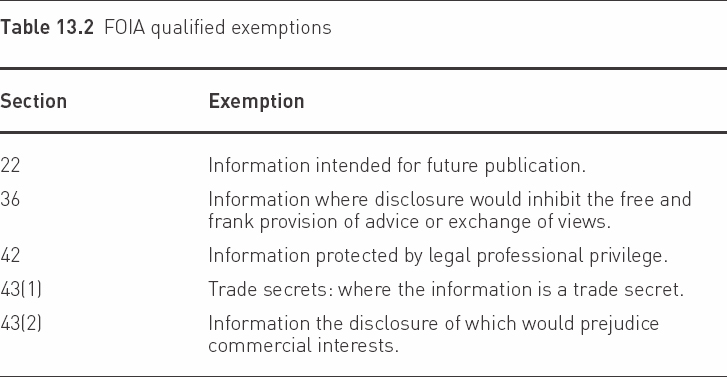

For the purposes of private sector companies engaging with the public sector, the most common exemptions that the public authority will consider in order to withhold information are set out in Tables 13.1 and 13.2.

The rules also allow public authorities to refuse to respond to requests where the request is designed to disrupt the working practices of the public authority. A public authority can refuse to answer a request that is vexatious or repeated as defined in guidance from the ICO and Tribunal decisions. Furthermore, a public authority need not respond to a request where the actual time spent determining whether the information is held, locating, retrieving and extracting the information would exceed certain time frames: 24 hours for central government and 18 hours for all other public authorities. The rule is known as the appropriate limit or cost limit and is set down in regulations. It also provides that the public authority can charge a requestor in certain circumstances, but it does not set out any mechanism for private companies to be reimbursed for any time spent assisting a public authority to comply with a request.

IMPACT OF FOIA ON PRIVATE COMPANIES

Private companies now have to operate on the basis that any information they provide to a public authority could be disclosed in the future. Such disclosures may take place regardless of the confidentiality clauses in any contract between the public authority and the private sector company since a statutory obligation to disclose outweighs any contractual obligation on the public authority. In other words, the public authority may have to disclose confidential information under FOIA even if this disclosure would put it in breach of contract. This may give rise to commercial, reputational and privacy risks for the private company.

Commercial

Much of the information that a private company provides to a public authority will relate to business practices or commercial matters within the private company. There are a number of exemptions that may be relevant here and we set out below brief background on two exemptions in particular: confidential information (s. 41) and commercial prejudice (s. 43 (2)).

The test in relation to confidential information requires a number of different elements. Firstly, the information must have been obtained from another party (i.e. not the public authority). Secondly, the information must be confidential. Thirdly, the information must have been imparted in circumstances importing an obligation of confidence (i.e. the receiving party should have been reasonably aware that the information must be held in confidence). Fourthly, the disclosure of the information must be to the detriment of the party providing the information to the public authority. Fifthly, there must be no public interest defence to the disclosure and, lastly, any action for breach of confidence should, on a balance of probabilities, succeed.

The test in relation to commercial prejudice is whether, at the date of the request, disclosure of the information would be likely to damage a party’s commercial interests (whether the public authority, computer company or another party). Therefore, if consulted by the public authority about a FOIA request, or in identifying information that may fall within this description for inclusion in a schedule to the contract listing confidential and commercially sensitive information, the company needs to be able to clearly distinguish between information that is not really commercially sensitive and information that is. In support, the company should provide arguments about the damage the release of such information will actually cause the company (i.e. disclosing unit prices would allow competitors to undercut the company’s position). Furthermore, to the extent that the company can assist the public authority in considering the public interest factors (since s. 43 (2) is a qualified exemption), the company should provide the public authority with arguments that the public authority can then consider when deciding whether it can rely on an exemption. The Office of Government Commerce Civil Procurement Policy and Guidance provides a useful starting point for thinking about when this exemption might apply to specific information.

Reputational

It goes without saying that disclosure of information under FOIA can have a serious effect on the reputation of numerous actors: the public authority as well as third parties involved.

Privacy

Depending on the information that is disclosed, there can be risks to individuals’ privacy if information about their public or private role is disclosed.

DEALING WITH FOIA

Private companies should follow these steps:

- Prepare for company information to be put into the public domain particularly in light of the Transparency Agenda.

- Devise a PR strategy for dealing with this eventuality.

- Think carefully about the information provided to public authorities and in what context. Public authorities will not necessarily know how sensitive the information is to the company unless they are told. A public authority could be entitled to consider that information provided voluntarily, without any warning to a public authority about its sensitivity, could be disclosed under FOIA.

- When entering into contracts, ensure that there is a robust FOIA clause that requires the public authority to notify and consult the company when it receives a request that affects company information.

- If the company is providing a service to a public authority that involves the company collecting information on behalf of the public authority, bear in mind that the company will be holding information on its behalf and, therefore, such information is subject to FOIA. As a result, the public authority may require the company to help with compliance with its responsibilities under FOIA by searching for and locating this information. This activity may impact on the company’s resources depending on how many requests of this nature are received. The company should consider at contract negotiation stage whether it is prepared to absorb these resource costs or whether it proposes to charge the public authority for this assistance.

- When entering into a contract with a public authority, seek to identify early on the information that is confidential or commercially sensitive to the company and identify this information in a schedule to the contract explaining why the exemption should apply and providing any public interest arguments. This is particularly important due to the new Transparency Agenda, which requires the proactive publication of IT contracts. Although this is not a guarantee that this information will not be disclosed it does provide a clear indication of the views of the parties at the time the contract was signed.

- Seek to be involved in helping the public authority assess the relevant exemptions when information is requested. However, do not try to control the public authority’s FOIA process and be realistic about the information the company wishes to withhold. A blanket exemption for the whole contract is not going to be persuasive. Furthermore, a public authority is not obliged to take account of the company’s arguments and can still disclose regardless of what the company says.

- The ultimate remedy available to a private company if a public authority is due to disclose information that the company considers is exempt from disclosure is to seek an injunction to prevent disclosure. In reality, hardly any companies have gone down this route and the company will need to have been informed in advance that a disclosure is due in order to seek an injunction preventing disclosure.

PROCUREMENT

When bidding for substantial public sector IT projects, the tender process is run according to UK procurement rules. Under procurement rules, public authorities are required to disclose certain information at particular points in the procurement timetable. For instance, once a contract award decision has been made, the public authority must provide all those expressing an interest in tendering for the work (besides the successful tenderer) with information such as the award criteria and weightings, the score that the particular recipient obtained against those award criteria and weightings, and the score that the winning tenderer obtained. On the basis that this information is intended for future publication, once the award has been made, a public authority may well consider applying the exemption under s. 22 (along with any other available exemptions) if it receives a request for disclosure of this information before it has been published to the interested parties. However, to rely on this exemption, the public authority must be able to demonstrate that it is reasonable in all the circumstances that the information should be withheld from disclosure until the date intended for publication. Additionally, since s. 22 is a qualified exemption, the public interest test applies.

DRAFTING A CLAUSE

The following lists some issues that a private company should consider when negotiating a contract or non-disclosure agreement with a public authority:

- Is the public authority required to publish the contract as part of the Transparency Agenda?

- Is there an opportunity to provide a schedule setting out the information you consider to be confidential or commercially sensitive?

- Will the public authority notify you if it receives a FOIA request that relates to information you disclose to the public authority in connection with the contract?

- If the public authority agrees to notify you, will it do so immediately or use reasonable endeavours to do so or within a specified time period?

- Is there any obligation on the public authority to consult with you when a FOIA request relates to information you disclose to the public authority in connection with the contract?

- Is the public authority under any contractual obligation to take your arguments into account when applying exemptions?

- If you will hold information on behalf of the public authority under the contract, under what circumstances can the public authority require you to search for and provide information in response to a FOIA request?

- Will the cost of the resources you apply to searching and providing information be paid for by the public authority or will you absorb these costs?

- To what extent are you required to search for information?

- Within what time limits are you required to provide this information?

FURTHER INFORMATION

Information Commissioner’s Office: www.ico.org.uk

Information Tribunal: www.informationtribunal.gov.uk

Ministry of Justice and FOIA: www.justice.gov.uk/about/freedom-of-information.htm

Ministry of Justice Section 45 Code of Practice: www.justice.gov.uk/guidance/docs/foi-section45-code-of-practice.pdf

OGC Civil Procurement and Policy Guidance (v2): www.ogc.gov.uk/documents/OGC_FOI_and_Civil_Procurement_guidance.pdf

OGC Transparency: www.ogc.gov.uk/policy_and_standards_framework_transparency.asp