14 RESOLVING DISPUTES

Sara Ellacott

This chapter considers the most commonly used methods of dispute resolution, their advantages and disadvantages, together with a consideration of the relevant procedures associated with each method. Mediation is discussed after litigation and arbitration, but you should note that it has gained popularity in the UK with the courts, government agencies and the private sector.

INTRODUCTION

Taking time to consider how to deal with potential disputes at the very outset of a complex technology project can sometimes be regarded as defeatist; the parties are keen to work together and do not want to dwell on the potential difficulties they may face. The reality, however, is that during the life cycle of the majority of technology projects a variety of disputes will happen for a wide variety of reasons:

- business requirements change;

- delays mount up;

- complex terms give rise to various interpretations.

Despite the best intentions of the parties, careful planning and excellent working practices, problems can and do still arise. Time is therefore well spent considering the various methods of dispute resolution available, before the need to use them actually arises in practice.

OVERVIEW OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION METHODS

There is a wide range of potential dispute resolution methods available, the most common of which are:

- negotiation;

- escalation to senior management;

- expert determination;

- litigation;

- arbitration;

- competition bodies (e.g. OFT, European Commission);

- mediation.

There is no ‘one size fits all’ method of dispute resolution, so your choice will ultimately depend on what you require out of the dispute resolution process, for example:

- Do you require damages/compensation for a particular breach of contract or misrepresentation?

- Is obtaining interim injunctive relief a necessity?

- Is an ongoing relationship important?

- Is it important to maintain confidentiality as to the issues in dispute and the resulting settlement (if any)?

Depending on your needs, the different methods of dispute resolution will be more or less suitable.

KEY FACTORS IN DISPUTE RESOLUTION

When deciding on any dispute resolution method, there are a number of common factors that should always be taken into account. These include:

- Impartiality–is the adjudicator impartial and seen to be impartial?

- Expertise–has the adjudicator the correct level of expertise to deal with the issues in dispute?

- Speed–how long will it take the adjudicator to reach a decision?

- Cost–how expensive will the process be?

- Certainty–will the decision be binding and can it be appealed?

- Confidentiality–will the decision/settlement be confidential?

- Motivation–who, if anyone, has a vested interest in the dispute and its resolution?

- The business relationship–can the relationship continue after the dispute is resolved?

- Ease of enforcement–can the decision be enforced domestically and/or abroad?

Each method of dispute resolution has its advantages and disadvantages, and we will consider each method against these key factors before addressing the relevant procedures associated with it.

SPECIFIC DISPUTE RESOLUTION METHODS

Negotiation

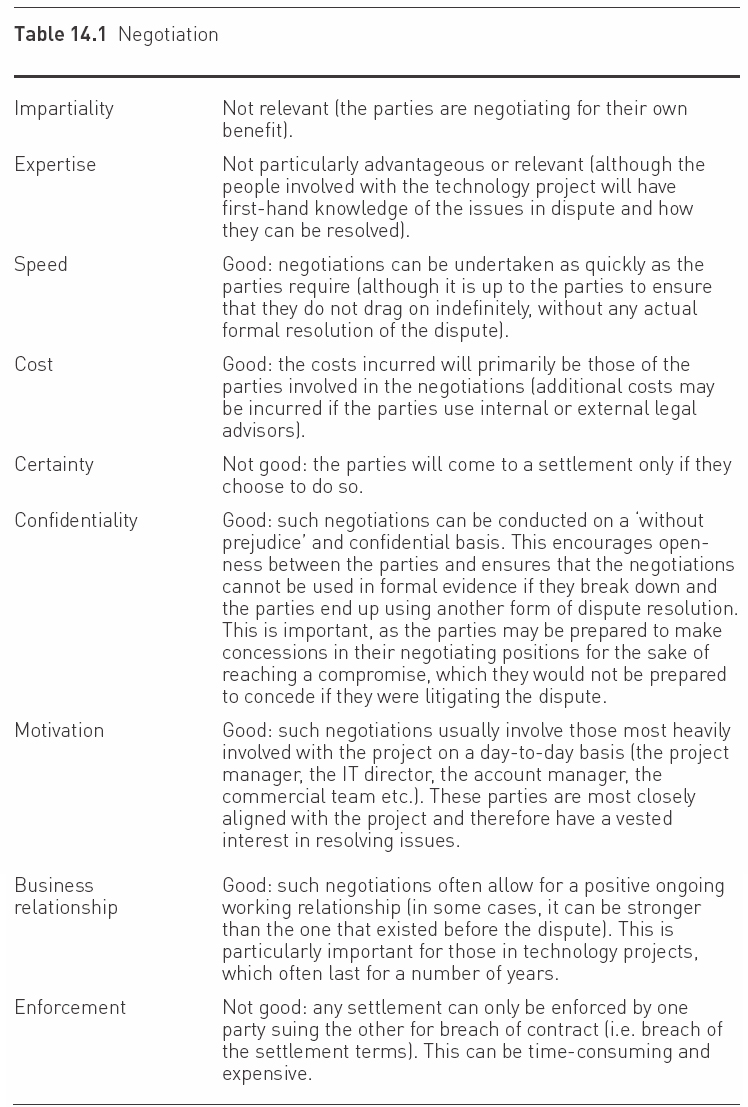

Direct commercial negotiation between the parties is one of the most popular and successful ways of resolving disputes. Table 14.1 shows how negotiation relates to the key factors.

Escalation to senior management

Some technology contracts require that the parties try and resolve disputes through senior management before resorting to external methods.

The advantages and disadvantages of this method are generally very similar to those of negotiation, but there is a particular ‘plus’ when it comes to motivation. Sometimes those at the ‘coalface’ of a large-scale technology project can become too emotionally involved to resolve a dispute: they allow their personal prejudices to prevent them seeing the advantages of a commercial resolution. Escalation to senior management can cut through such prejudices, and so allow for the ‘bigger picture’ to be considered and a commercial resolution found.

Expert determination

Expert determination is now a very popular method of dispute resolution in the construction industry, and it is also well suited to the settlement of technology disputes (although its take-up in the IT sector has not been as widespread as many people had previously envisaged).

It is a procedure by which an independent third-party expert makes a decision on the dispute. The expert does not act as a judge or as an arbitrator. Table 14.2 shows how expert determination relates to the key factors.

The procedure adopted for expert determination depends on the terms of the parties’ contract (although they may decide to put a dispute to expert determination by later agreement). The ‘terms of reference’ set out how the expert is required to act and should include clear definitions of:

- the issues under dispute;

- the material the expert is expected to review;

- what the expert is allowed to consider (matters may arise from investigations that the parties to the dispute feel the expert is not equipped to deal with);

- the procedure and timescale to be followed;

- the nature of the submissions each party is allowed to make;

- what type of hearing is required;

- how the final decision is to be delivered (i.e. orally or in writing).

The expert is usually appointed from a recognised body. The parties may appoint a panel of experts rather than an individual; each person having been selected to provide a different type of expertise and perspective.

The parties may agree grounds upon which a decision may be challenged.

If there is no express agreement, then common law inserts the following grounds as reason for appeal:

- Fraud by the expert;

- Failure by the expert to treat the two parties fairly or equally;

- A ‘material departure’ from the instructions by the expert (any departure from the instructions that is more than trivial will be a ‘material departure’ irrespective of the consequences);

- A ‘manifest error’ by the expert (i.e. a blunder or omission capable of affecting the determination). It must have a significant consequential effect on the outcome of the determination; a minor mistake will not render the decision invalid, unless the parties have agreed that it will in their terms of reference;

- An error in an accountant’s certificate that details the adjustment in value of a purchase price when that price is being determined by the expert.

Litigation

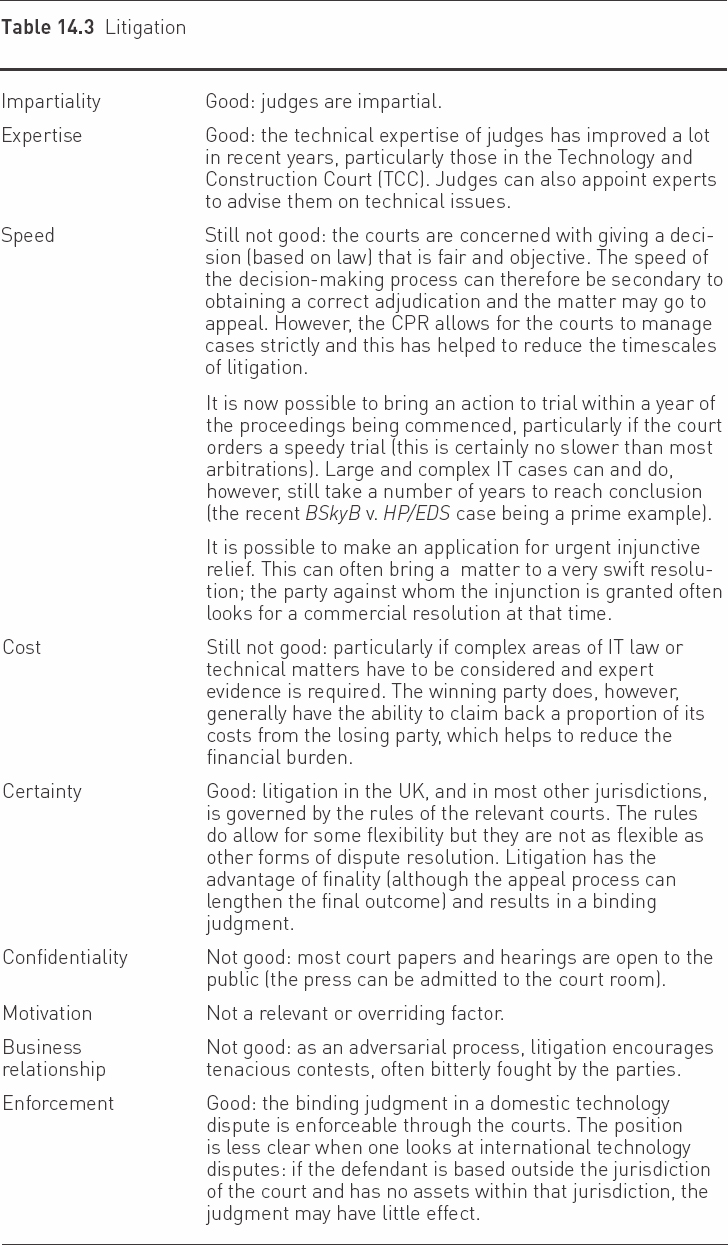

Litigation is the traditional method of resolving contractual disputes. The landscape of civil litigation changed with the introduction of the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 (CPR). The CPR continues to place an emphasis on the front-loading of legal costs, by the parties having to properly set out their claims at an early stage in the proceedings. Table 14.3 shows how litigation relates to the key factors.

The procedure for litigation is:

- The party who believes its rights have been infringed (the ‘claimant’) sends a ‘letter before action’ to the infringing party (the ‘defendant’). It is essential that the letter before action sets out the claim in sufficient detail to enable the defendant to fully understand the case against it. Thus the claimant generally must undertake a significant amount of preparation before sending this letter. When dealing with IT issues, this preparation can be particularly detailed and time-consuming. Failure to send such a detailed letter can have costs implications at the end of the case.

- The defendant will usually respond in writing to the claimant’s letter before action. At this stage, the parties may also attempt to negotiate a settlement on a ‘without prejudice’ basis (or explore alternative dispute resolution methods, particularly if required to do so by a contract between them, or the courts).

- If the parties are unable to reach settlement, the claimant may elect to issue legal proceedings in the appropriate court (most likely the Technology and Construction Court (TCC)). The claimant must serve upon the defendant a ‘claim form’ (a formal court form containing brief details of the claim) and ‘particulars of claim’ (a more detailed document setting out the claim and the remedies sought).

- The defendant must acknowledge service of the claim and may at that stage elect to admit the claim, or defend all or part of it. If intending to defend the claim, then the defendant must file with the court a ‘defence’ (a response to the claim, including the reasons why the defendant is not liable). A defendant who also has a claim against the claimant may file a ‘counterclaim’ (a document similar to the claimant’s particulars of claim). If the defendant fails to acknowledge service of the claim or file a defence, the claimant may apply to the court for judgment in default of a defence.

- The court allocates the claim to the appropriate ‘track’ (small claims, fast-track or multi-track), depending upon the value and complexity of the claim. Technology disputes are dealt with by way of multi-track. Each party completes an allocation questionnaire providing details about the dispute, to assist the court with allocation.

- The claimant may also choose to serve a ‘reply’ to the defendant’s defence and a ‘defence to counterclaim’ if appropriate. (If the claimant fails to defend a counterclaim, the defendant may apply for judgment in default.) Unless there are exceptional circumstances, the claimant’s reply and defence to the counterclaim brings an end to the process by which the parties set out their legal positions in writing. The remainder of the litigation process focuses upon the collection and exchange of each party’s evidence.

- The court sets the timetable (or directions) for the further steps in the proceedings, including disclosure and inspection of the parties’ documentary evidence, exchange of witness statements and expert reports, dates for any interim hearings (e.g. the trial of a preliminary issue or a pre-trial review). The court is guided by information provided by the parties in their allocation questionnaires, which may include each party’s preferred directions. The court may also order that the parties attend a hearing, known as a case management conference, to discuss directions. It is a particular feature of the CPR that the courts now take a very ‘hands on’ approach toward case management. It is fairly common for the directions to include a short stay of proceedings for the parties to attempt to reach settlement by alternative dispute resolution methods, such as mediation.

Following completion of the steps set out in the timetable for directions, the matter will go to trial. Trial may take the form of a single hearing, or the court has the option of trying a key preliminary issue on its own, on the basis that if this is decided in a certain party’s favour it may end proceedings (or encourage an out-of-court settlement) and save the cost of a full hearing. After hearing the parties’ cases at trial, the court gives its judgment and may grant leave to appeal.

There may also be a separate hearing to determine how legal costs are to be divided between the parties (generally the losing party pays the winner’s costs, although the courts have a wide discretion to order costs on the most appropriate basis). If a party fails to comply with any order of the court, it may be necessary for the other party to go back to court to seek a further order for enforcement.

Arbitration

Arbitration is seen as the traditional alternative to litigation. It is a private and binding adjudicative process and was conceived as a way of providing a solution for commercial disputes in a practical and cost-effective way. Table 14.4 shows how arbitration relates to the key factors.

The framework for arbitration is governed by statute. Contracts often contain clauses that refer any dispute to arbitration. If such a clause exists, the parties must adhere to it rather than issuing proceedings in the courts.

The parties to the contract select the arbitrator together on the basis of expertise in the field from which the dispute stems or on which the contract is based.

The arbitrator’s conduct is governed by the ordinary rules of natural justice, evidence, and the civil burden of proof (the case must be proven ‘on the balance of probabilities’). The parties are, however, at liberty to dispense with the ordinary rules of evidence and allow the arbitrator to carry out a more inquisitorial role.

If there is no governing arbitration clause, the parties may opt to engage in arbitration by agreement. In this instance, the parties meet and agree the terms of the arbitration agreement after the dispute has arisen. As is the case when an arbitration clause in a contract is being drafted, the parties are at liberty to determine the timescale, applicable law, procedure, and venue of the arbitration as well as the arbitrator they wish to use. In effect, the parties tailor the personnel, procedure and hearings to their particular needs.

During the arbitration proceedings, the arbitrator gives directions and may hold hearings in much the same way as a judge would in litigation proceedings. The arbitrator does this in accordance with the rules adopted by the parties, be they of their own invention or adopted from a particular institution’s prescribed rules. The arbitrator may have to decide on the rules of the arbitration if the parties are unable to agree. The parties are able to refer issues to the courts if the arbitrator is guilty of any misconduct. The courts may also determine points of law and support the arbitrator by making various orders.

The arbitrator will hold a final hearing at which he or she will make an award to one of the parties. There is no requirement for the arbitrator to give reasons for the award he or she makes. However, if one of the parties asks for reasons and he or she refuses to give them, then the court (on application from the party concerned) may order him or her to do so. The award made is legally enforceable against the other party, but a party is allowed to appeal to the court against an award on a point of law.

Mediation

Mediation involves the appointment of an independent, qualified mediator (or mediators) to assist the parties in reaching an agreed settlement. A mediator does not usually have an adjudicative role in the proceedings, nor is it the mediator’s role (unless expressly asked to do so by the parties to the mediation) to pass judgment, or to give an opinion on the merits of the parties’ individual cases. Rather, the mediator’s role is to facilitate the resolution of the dispute in question.

The use of mediation in the technology industry has continued to increase, particularly as parties to a dispute now face increasing pressure from the courts to resolve their differences through alternative dispute resolution methods rather than court proceedings. The CPR states that the court must further the overriding objective by actively managing cases, including ‘encouraging the parties to use an alternative dispute resolution procedure if the court considers that appropriate and facilitating the use of such procedure’, and there has been a corresponding increase in court-ordered mediations.

Moreover, the government is encouraging the use of mediation in the public sector. Under the Lord Chancellor’s Pledge, alternative dispute resolution methods should be considered and used in all suitable cases wherever the parties accept it. This covers government departments and agencies.

If a party in a technology dispute refuses an invitation to mediate, without a legitimate reason for such a refusal, it may risk being criticised by the courts should the dispute result in legal proceedings. That party could also face cost penalties regardless of the outcome of such legal proceedings, should a court consider a refusal to mediate to constitute unreasonable conduct.

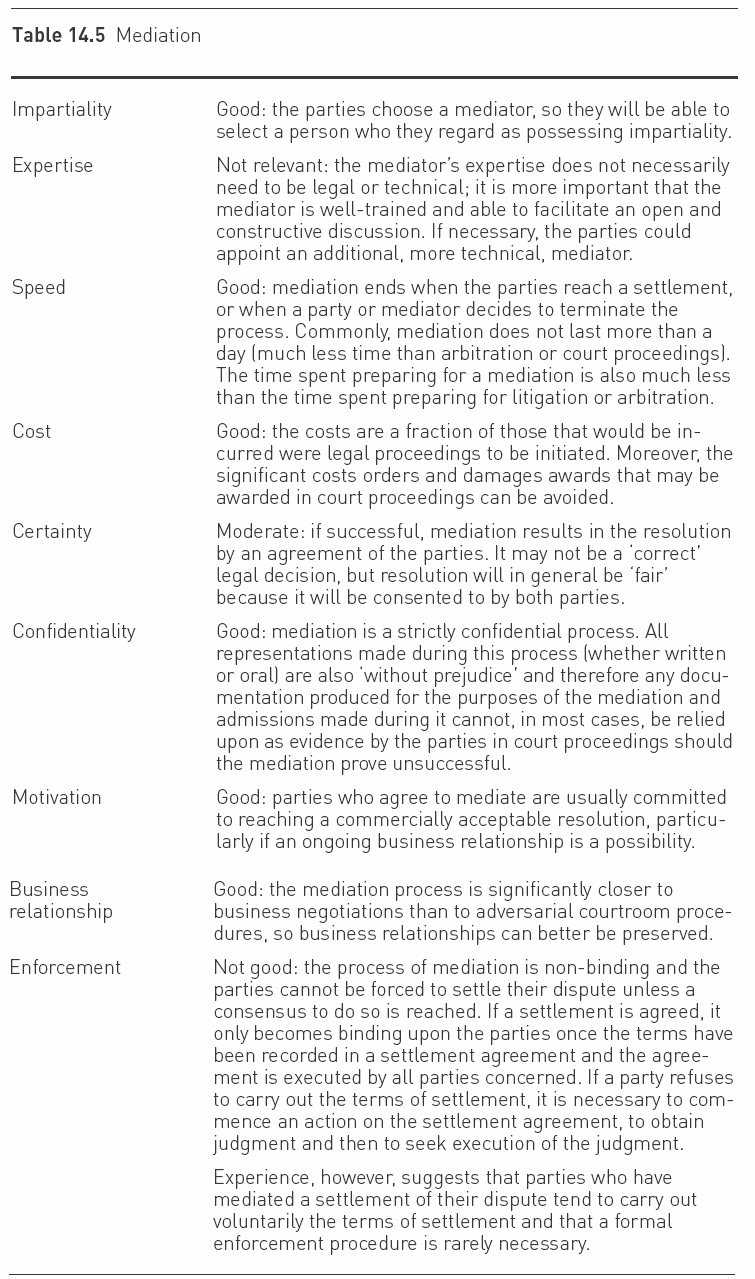

Table 14.5 shows how mediation relates to the key factors.

The parties are expected to agree upon a choice of mediator. The choice of mediator will invariably be determined by the nature of the dispute, and the mediator may be a lawyer, an accountant or a technical expert. In the IT industry, a legally qualified mediator with knowledge of the industry, or possibly a technically-qualified expert, would be preferable. A venue for the mediation also needs to be agreed upon. This is usually a venue independent of the parties.

The process usually follows this format:

- The parties prepare written case summaries that are exchanged with each other and provided to the mediator in advance of the mediation. This allows the mediator to understand the issues in dispute and the parties’ respective positions. The case summaries should highlight any facts and issues that have been agreed by the parties as well as those that remain in dispute. These summaries are usually supported by an agreed bundle of relevant documentation to which the parties can refer in their summaries. This is usually made up of contracts, correspondence, notes of meetings, relevant technical papers etc. The mediation takes place shortly after the exchange of case summaries and copy documentation.

- The mediation commences with a joint session attended by all the parties (and their legal representatives) and the mediator, at which the parties are invited to give a short presentation of their positions in relation to the dispute.

- The parties retire to separate rooms and a series of what are termed ‘caucus’ sessions commence. The sessions involve the mediator visiting each of the parties to discuss and explore their respective legal positions. The mediator will use these caucus sessions to establish if there is any middle ground between the parties that may form the basis of a negotiated settlement.

- The mediator may call the parties back for further open sessions to discuss any progress that has been made or issues that have been raised.

- If the parties are successful in establishing a commercial resolution to the dispute the mediator will expect them to sign up to written terms of settlement prior to the close of the mediation. Most mediation organisations insist upon the parties having personnel with the appropriate authority to settle the dispute. Mediators are particularly keen on any agreement reached being drawn up and signed by the parties on the day of the mediation because this avoids the parties subsequently disputing the terms of any agreement reached.

CONCLUSION

There is no ‘right answer’ when choosing a dispute resolution process. Each dispute resolution method has advantages and disadvantages that will play a part in the decision-making process.

The courts, and the increasing range of arbitration bodies, continue to take action to improve their offerings as dispute resolution providers. Mediation also continues to gain popularity in the UK as a commercial and cost-effective way of resolving disputes. A refusal to consider the available dispute resolution methods could have heavy cost implications, and they are accordingly worth addressing properly during the contract negotiation phase of a technology project, as well as in the early stages of any actual dispute.