2 Tourism at Coranderrk

Tourism at Coranderrk Aboriginal station has been researched by Lydon (2005), however her concern with tourism is primarily to provide context for her reading of the photography that visitation produced. Lydon’s (2005) study of Coranderrk has shown how this station became a ‘showplace’ of Aboriginal culture, and how it was visited by many local and international visitors many of whom have left a photographic record, such as Charles Walter, Enrico Giglioli, Frederick Kruger, Claude-Joseph Désiré Charnay, Nicolas Caire, and Ernest Fysh, who were keen to participate in what they thought was ‘the work of salvage, collecting information and taking photographs to serve as scientific data’ (Lydon, 2005: xx). People were also motivated by an interest in Aboriginal people they regarded as both a ‘dying race’ and a ‘fossil race’. Indeed, in the early 1900s tourist guides often promoted a visit to Aboriginal stations and the purchase of postcards of the stations and their residents as important souvenirs of a soon-to-be extinct race of people (Lydon, 2005: 189).

Lydon (2005: 22) has observed ‘Coranderrk was unusual in its level of contact with European society: the station’s proximity to white settlement saw a constant flow of visitors toward it … the problem of maintaining the residents’ seclusion became a constant theme’. Coranderrk became akin to a zoo or laboratory. Lydon (2005: 22f) further notes that once the Board had ‘enforced its assimilation policy in the mid-1880s, the Board allowed the station to become a showplace, open to visitors, and as tourism out of Melbourne developed, Coranderrk became a must-see site on an itinerary that extended northeast into the Dandenongs’.

Under John Green’s leadership, the Coranderrk residents had been allowed to develop their own internal organization – decision making was consensual via a council of elders; the siting of resident houses was permitted in accordance with traditional social organizational practices; punishments were meted out by a residents’ court; and movement on and off the station was regulated by the elders. As Green explained, ‘My method of managing the blacks is to allow them to rule themselves as much as possible’ (Lydon, 2005: 15). The older residents were permitted to continue to live in traditional dwellings (or willams or mia-mias) (see Figure 2.1), and to bury their excrement as they always had so that it could not be accessed by their enemies and used for traditional harming practices. When worshipping the traditional segregation of men and women was maintained. In this context then it was only logical that Aboriginal people would also expect to control external processes that sought to incorporate them such as tourism and photography. Tourism gave residents an opportunity to sell souvenirs and to participate in sporting and cultural events in Healesville and in Melbourne, and it also allowed them ‘to develop a sophisticated awareness of white discourse’ (Lydon, 2005: 23).

Kleinert (2006: 84) has argued that the tourism that developed at Coranderrk and Lake Tyers ‘was a response to a growing fascination on the part of an urbanised populace for a unique experience of an exotic “primitive “, conflated with the picturesque natural beauty’ that these two localities offered. Seeing tourism as an important form of cross-cultural exchange, she notes that in the late 1800s and early 1900s ‘many hundreds of tourists visited Coranderrk and Lake Tyers particularly during the summer months’. At Coranderrk, as the analysis that follows will detail, tourists were able to see boomerang throwing, fire lighting, spear throwing, tree climbing, basket making, hear stories from leading men such as Barak, and take their own photographs or buy locally produced photographs and postcards. As mementos of their visit they were able to purchase their own baskets, rugs, boomerangs, spears, fire-lighters, and paintings. John James, a.k.a. The Vagabond (The Argus, 23/5/1885) was dismissive of the tourism at Coranderrk where Metropolitan cockneys and globe trotters from Manchester and Birmingham could get their first impression of the ‘Australian black fellow’ and purchase badly-made curios to take home, mementos of their experiences with the ‘“Savage” of Australia in his native lair’.

2.1 Tarra Bobby, the Brataualung, and Acheron Station, April 1860

One of the earliest visitor accounts is that of a Brataualung Aboriginal man named Boon-bul-wa, aka Tarra Bobby, who belonged to the Warrigal Creek and Tarra River district in Gippsland, who visited the Acheron Reserve in April 1860 (Stephens, 2014 v. 3: 265). There he found Aboriginal people working the land ‘like white man’ under the guidance of Robert Hickson. Attwood (1987: 47) observes he was most excited by what he saw and on his return to Melbourne gave William Thomas ‘a glowing account of blacks working hard, making paddocks &c. &c.’ telling him ‘blackfellows Gippsland by and by like that’. Attwood (1987) has made a special study of Tarra Bobby and confirms that he belonged to the Yauung group (or band) of Brataualung that was centred on Warrigal Creek and the Tarra River. Attwood (1987: 47) suggests that ‘[m]uch of Bobby’s optimism was due to the fact that the Taungurong had bestowed a young woman, Annie, upon him in accordance with the practice of exchanging women between distant clans’. After his marriage he returned to Gippsland to inform his people about Acheron and in June some 100 Kurnai came to visit Acheron. By winter of 1863 Tarra Bobby, his wife Annie, and another Brataualung man, Bobby Coleman, went to Coranderrk. On 27 May 1863 a deputation from Coranderrk attended Victorian Governor Sir Henry Barkly’s public levee or reception in Melbourne to honour the recent marriage of the Prince of Wales and the Queen’s birthday. At the levee they presented gifts to Prince Albert to equip him in his new role as a married man and birthday gifts of rugs and baskets were presented to the Governor to be passed on to the Queen (see Clark, 2014a). The Argus (27/5/1863) confirmed that the Aboriginal delegation represented the ‘Waworrung, Boonorong, and Tara-Waragal tribes’. Presumably, the representative of the Tara-Waragal here referred to is either Boon-bul-wa (Tarra Bobby) or Bobby Coleman.

2.2 Rev. Robert Hamilton’s Impressions of Coranderrk, August 1864

One of the first to visit Coranderrk was the Presbyterian Rev. Robert Hamilton (The Age, 6/8/1864). This visit was the beginning of a long association with the Coranderrk residents.

Sir, – As many of your readers are doubtless interested in any scheme that is likely to improve the condition of the aborigines of this country, I beg to communicate some information respecting a settlement of the blacks on the Upper Yarra. This aboriginal station has a Government reserve of 2300 acres about 40 miles from Melbourne, and is situated on what is called “The Yarra Flats.’’ The place receives the name of Coranderrk. It is well supplied with water, having the Yarra and Badger’s Creek on the one side, and Watt’s River on the other. Three sides of the settlement have a water frontage all the year round — the creek mentioned, and the smaller river having a constant flow of beautiful water summer as well as winter, and the remaining side has a natural fortification of mountainous ranges. The reserve once formed part of Mr W. Nicholson’s station and was secured for the blacks at the time that gentleman was in office in the Government. The spot is exceedingly well suited to the purpose for which it has been selected. It is secluded, and thereby fitted to preserve the natives from free and injurious intercourse with the whites.

Hamilton reported that the reserve was rich in native game: ‘The greater part of the station is covered with bush, and contains, of course, abundance of firewood, and, what is of great importance, a considerable amount of game. The kangaroos, and opossums, the wombat and native bear, the wild duck, parrot tribe, magpie, swan, &c. are all found here, and often yield to the fatal shot of the natives’ (The Age, 6/8/1864). In terms of the residents, Hamilton explained that there were 67 Aboriginal people on the settlement at the time of his visit, representing various tribes: the ‘Yarra and Goulburn embrace a large proportion. One is from the Murray; a few are from Gipps Land and Seymour. A number have come from Franklinford… Besides those, there is a large number of blacks who regard these as their friends, either by family and tribe connection, or by interest and other considerations, and are likely, sooner or later, to come and settle with them. The number of the whole would, in that case, be about 140’. ‘They are all dressed in European clothing, not received in charity, but acquired by the earnings of their own industry’. He considered that one of the obstacles they had to overcome was the requirement that they learn English ‘with which they must be very imperfectly acquainted. The progress which heathens in other lands make under missionary teaching is doubtless very much facilitated by the teachers first learning the language of the people, and then imparting knowledge to them on all subjects in their mother tongue. Were it not for this hindrance, I have no hesitation in saying that, other circumstances being alike, the natives of this country would make as much progress in a given time as the savages of other climes do under missionary labor’

Hamilton found it interesting that the Coranderrk residents were ‘of a disposition to form an independent judgment on matters. They wish to have minds of their own; and, while they respect and love Mr Green in a high degree — even as a father, a friend, or a chief — yet they are not disposed by any means to be always bound by his opinions and views. And sometimes a little reasoning is necessary to bring them to right plans’. The residents displayed this independence many times over the next sixty years and would be a constant irritation to some members of the Board who had their own idea on what was in the best interests of the residents.

Attending worship, Hamilton noticed that certain decorum and rituals were observed in the seating arrangements and when leaving the chapel:

At the close of all the speechifying, which was to all appearance greatly enjoyed, worship was conducted as usual, and a short exposition of Scripture given. Immediately after the religious service, the women, who sit all on the left side of the room after entering, while the mon all sit on the right, are the first to rise, and one by one to shake hands with all the children and white people, but not with the male adults, and then retire to their huts. Next the men rise, and one by one also shake hands in a similar manner and then retire. The separate classification of males and females, and the great hand-shaking morning and evening, by invariable custom, originated entirely with themselves. Shaking hands, as a mark of goodwill, is quite an institution among them, and if you meet them several times a day, it is only what is expected, that you as often observe the ceremony (The Age, 6/8/1864).

Although Hamilton was silent on the manufacture of rugs, the Central Board (Victoria, 1864: 5) in its annual report announced that ‘They have made a great number of rugs, which have been sold for about £70’.

2.3 Making progress at Coranderrk 1865

The Age newspaper kept its readers informed of the progress of Coranderrk, and when it was not sending its own reporters to the station; it would summarize annual reports published by the Central Board, such as the following for 1865:

On the 22nd June, 1865, two members of the Central Board – Mr. John Mackenzie and Mr. Brough Smyth – visited this station. They arrived, they believe, unexpectedly, and found the station in its ordinary condition. They inspected the huts and houses at nine a.m., and found them clean, neatly swept, and very comfortable. Many of the interiors were tolerably well furnished, the seats and tables being made of rough bush timber, and the walls decorated with pictures cut out of the Illustrated London News and the illustrated papers published in Melbourne. There were also several photographs, which were highly prized by the aborigines. There were 105 blacks on the station at that time, and there was scarcely one of them who was not in robust health. Wonga, a very intelligent aboriginal, showed them some opossum skins which he had tanned with the bark of the native trees, and he showed that he was fully competent to discriminate the barks and select the best.

On the 14th July, 1865, the Central Board received a general report from Mr. Green, extracts from which will be read with interest, he says:

The old men generally hunt every fine day, but the young men hunt only two days in the week. They work on the other four days. They make rugs with the skins of the opossum, kangaroo, and wallaby, for each of which they get from £1 to £1.15s.With the moneys thus obtained they buy boots, hats, and clothes, powder and shot, and occasionally meat. Tommy Hobson has bought a good mare, and a saddle and bridle. A few years ago I could not prevent him from spending all his money in drink; but now he has always money on hand, and he keeps himself, his wife, and three children, always well clothed. … The greater number of the women keep their huts, themselves, and the clothes of their husbands very clean. In their spare time they make baskets for sale, and with the money they get for these they buy little things for their huts. There are 104 blacks here. They are from six different parts of the colony; and there have been only a few cases of drunkenness since they came. They all agree very well. When any strife arises it is settled in a kind of court, held in the schoolroom, at which I reside.

Many persons who take an interest in the welfare of the aborigines, have from time to time visited this station; and, as far as the results of their observations are known to the board, they corroborate the statements of their officers (The Argus, 14/6/1866).

Barwick (1998: 83–4) has shown how the Coranderrk residents were able to raise their standard of living by their ‘canny’ expenditure of income from crafts and their wages. Visitors repeatedly commented that their homes and furnishings were equal to those of ‘English workingmen’ and superior to many selectors in the district.

The women sold their baskets, eggs and fowls to visiting pedlars for fashion books, dress lengths and trimmings and then paid itinerant photographers to record their finery. Most of their furniture was home-made but they eagerly saved for sofas, chiffoniers and rocking chairs, curtains and wallpaper, clocks for the mantelpiece, pretty ornaments and tea cups, sewing machines and perambulators, spring carts and harness and guns, as well as all the utilitarian bedding, dishes, cutlery, candles and kerosene lamps not supplied by the Board. In addition to spending large sums in the Healesville shops they ordered furniture and other goods from Melbourne, and the manager in 1877 complained that ‘there is no end to their propensity for good dress when they have the money’. They also spent their money on novels and newspapers although the station had a library of ‘improving works’. The illustrated weeklies contained engravings of stirring events and portraits of Her Majesty do decorate their walls; the Melbourne daily newspapers, the Age, and Argus, were their main source of information on Board decisions. Rugs made from wallaby and possum skins, once worn as cloaks, took a fortnight’s stitching but had a ready sale in 1865 at 20 to 35 shillings each. These and other indigenous manufactured goods – nets, weapons, bags and baskets – were a spare-time industry for the women and the aged. The sale of such crafts supplemented the income from crops by an average of £100 a year to 1874 but lessened as materials grew scarce (Barwick, 1998: 83–4).

2.4 1866 Intercolonial Exhibition

The Ballarat Star reported that Coranderrk Aboriginal people were preparing to exhibit their crafts at the forthcoming Intercolonial Exhibition.

A number of the aborigines in the district of Coranderrk, Healesville, have expressed their intention of competing at the forthcoming exhibition, opossum skin rugs, baskets, &c., being the articles in which they intend to exhibit their emulative skill to the test of public verdict (Ballarat Star, 25/4/1866).

The Coranderrk residents were also presented at the exhibition, pictorially, as German photographer Charles Walter had been commissioned to prepare an exhibition of Aboriginal portraits to be displayed (see Lydon, 2005: chapter 2).

2.5 The Northern Wathawurrung Visit the ‘Blackfellow’s Township’, March 1866

In early 1866, after intervention from John Green, seven Wathawurrung children were taken to Coranderrk, and their parents left Carngham determined to visit the station and satisfy themselves that their children were well cared for. They remained at Coranderrk for four months. Upon their return to Carngham, and the information they passed on about the ‘blackfellow’s township’, the rest of the northern Wathawurrung visited Coranderrk. When these people returned, they petitioned Porteous to apply to the Board for a block of land at Chepstowe for their use (Clark, 2008). Local guardian, Andrew Porteous reported on the results of their visit, that:

A number of the tribe have requested me to apply to the Government to reserve a block of land near Chepstowe for their use, where they might make a paddock, and grow wheat and potatoes, and erect permanent residences. I believe most of the tribe would remain permanently there if land was reserved for their use; their hunting is in the neighbourhood, and there is plenty of water. The young men seem to be very anxious about it; I believe this has arisen from hearing of the comfort and happiness of the Aborigines at Coranderrk. It would be little or nothing for the Govt. to reserve two sections for a year or two while the tribe lasted. A few more years will see them extinct.

In the early part of this year, seven youths were sent from this tribe to Coranderrk. They left Carngham at three o’clock a.m. in a spring cart, to get the first train from Ballarat, and by nine o’clock the same morning, the parents of four of the youths took the road and followed their children, and by slow but continued marches found Coranderrk, and their children comfortable and happy under the care of Mr Green. The parents remained at Coranderrk for upwards of 4 months, and then returned to inform the tribe of the comfort and happiness they had witnessed in the blackfellows’ township as they called it. On hearing their story, which was very interesting, the king made up his mind to take the whole tribe, and go to see the blackfellows’ township; and I have been informed that the Hopkins tribe intend to join them, and proceed to Coranderrk (Victoria, 1866: 13).

William Thomas, the Guardian of Aborigines confirmed the Wathawurrung clan head’s visit took place in 1866 when he was visited by 14 of the ‘Mount Emu’ people at his Merri Creek residence, en route to Coranderrk (Jnl 17/3/1866 in Thomas Papers, vol. 5). Porteous confirmed that the chief of the tribe and a number of others visited Coranderrk, and stayed there for a few weeks. ‘On his return, he described everything that he had seen, and he thought that the arrangements at Coranderrk were a great improvement on the former habits of the blackfellows (Victoria, 1869: 33)’.

2.6 Daniel Matthews, May 1866

D.M. from Sandridge, was another who reported on a ‘flying visit to the Aboriginal station at Coranderrk’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 12/6/1866). Coranderrk was part of a two-and-a-half-day stay at Healesville. In this embryonic period, Healesville boasted seven public-houses. D.M. is Daniel Matthews (1837–1902) who had a teaching association with the Sandridge (Port Melbourne) Wesleyan School in the early 1860s and who is known to have visited Coranderrk in 1866 (Cato, 1976: 27). Cato notes that he stayed several days and was impressed with the absurdity of the then prevailing notion that the Aborigines were some kind of poor beasts in human shape, incapable of learning. Matthews modelled his Aboriginal station ‘Maloga’ on the Murrray River near Moama in New South Wales after the Coranderrk station (see Cato, 1976).

THE ABORIGINAL STATION, CORANDERRK

Sir,- Having for a length of time promised myself a visit to the scene of Mr. Green’s labours as aboriginal protector, I resolved to proceed in that direction on Saturday evening. … The town of Healesville is as yet but small. It can, however, boast of seven public-houses. At a distance of two miles from Healesville, in the direction of the Yarra, and across a smaller hill of this mountainous district, in unpretending retirement on a gentle slope of the dividing range reclines the neat little native village of Coranderrk. The station is bounded on the south by the river. Yarra, and on the west by Badger’s Creek, which supplies a never failing stream, of delicious water. It contains 2300 acres, of first-class agricultural land, some of it possessing extraordinary richness. …The adults are quartered in nicely constructed bark huts, which form both sides of the main street of the township. The married folks have detached huts, while the single men and women have larger ones for their accommodation, and every means is employed to inculcate among them habits of cleanliness, neatness and order. Some of the more antiquated blacks consider this mode of life a sad innovation upon their former existence, and much prefer the primitive mia-mia to the modern hut. … From this little commonwealth of the reclaimed relics of the scattered tribes of our aboriginal brethren may be learned true lessons of happiness, peace, and concord. Friday and Saturday of each week are employed by them in their original pursuits – fishing and hunting. This I consider to be a wise step, as their attachment for home is greatly enhanced by this compulsory absence, and they return to its enjoyments with increased pleasure. …The experiment made at Coranderrk having proved so far successful, it is in contemplation to extend it. Government has been applied to and has granted two or three thousand acres on the Murray, somewhere near Echuca, for the purpose of another establishment.

D. M., Sandridge, 29th May (Empire, 11/6/1866)

One interesting residential aspect noticed by D.M. concerned the preference of the older people to live in traditional mia mias rather than occupy the cottages or huts supplied to them at the station (see Figure 2.1, which shows a man and his two wives at their willam or mia-mia). One of these residents was old Mary of the Ballarat tribe. ‘She could speak very little English and spent most of her time sitting at her camp entrance wrapped in a possum rug and smoking an old clay pipe. She usually had a small fire near, with a billy of tea beside it, as well as her cats and dogs’ (Symonds, 1982: 44). Massola (1969: 8) noted that the residents were in the habit of erecting miamias and bark huts in their ‘summer camp’ on the flat on the right hand side of the road where it crosses the Yarra River. In the 1920s he claimed it was still possible for travellers and tourists to pull up at these camps and obtain boomerangs and other weapons and beautifully made baskets. In the later years this access to passing traffic may have served to reinforce the value of continuing this traditional practice of living in willams or mia-mias.

Figure 2.1: Victorian Aboriginals and Mia Mia. John Kruger, photographer. (Author’s picture collection)

Diane Barwick’s analysis of Aboriginal women’s craft production has shown how vital it was to the viability of Coranderrk during its formative years in the 1860s and 1870s. Barwick claimed that the rush baskets and rugs the Aboriginal women and some old men made for sale at Coranderrk were more profitable in the early years than men’s participation in seasonal employment (Nugent, 2011: 78). In November 1867, R. Brough Smyth, the secretary of the Central Board visited Coranderrk and reported that in the homes the residents were in the habit of hanging native baskets up against the walls which were ornamented with pictures (Victoria, 1869: 19). He recommended that the residents ‘should also be encouraged to make baskets and rugs for sale, and the moneys got in this way, as well as by the sale of fruit, &c., should be paid into the consolidated revenue’, instead of being discretionary spending for the residents. Green persuaded the Board to refuse Smyth’s recommendation arguing that ‘the women and aged men had a right to profit from the crafts they made in their spare time’ (Barwick, 1998: 88).

2.7 Joseph Shaw’s Visit to Coranderrk, 1868

In 1868 Joseph Shaw, the young missionary at Yelta, on the Murray River visited the station and spent several days there. Little would he know that in 14 years’ time he would return to Coranderrk as its teacher, and become its longest-serving superintendent? He wrote of his 1868 visit:

A few weeks ago I spent a few days at Coranderrk Mission, and what I saw there filled me with joy. There was quite a little village of Aborigines, living in substantial cottages of bark, each cottage having two rooms. These were erected by the people themselves, under Mr. Green’s guidance. There are about 80 to 100 men, women and children living on the mission. The women are taught domestic duties and sewing, while the men are employed on growing wheat, oats, potatoes and vegetables, and other farm work. The children are instructed in reading, writing, and arithmetic, and several have made good progress. Each morning and evening all assemble for Divine Service in a large weatherboard schoolroom, and a more quiet and attentive congregation could hardly be found (Shaw, 1949: 14).

2.8 Sale of Coranderrk Baskets in Melbourne

In 1869 the Coranderrk residents had a retail outlet in Collins Street in Melbourne from which they were able to sell their craft. Sold through Reed’s Fancy Repository, the proprietor had agreed to sell them without charge or commission. The local papers ran with the story.

Says the Telegraph-.—Some interesting specimens of native basket work, from the aborigines station at Coranderrk, are now on view at Mr Reed’s fancy repository in Collins street, Melbourne, where they have been sent for sale. They consist of baskets and small grass basket nets, which are made by the aboriginal women and young girls while the men are employed on the farm or in hunting. The material used is the common coarse grass which is found growing in the swampy lands near Coranderrk. If encouragement be given to this industry the women and girls will soon produce elegant carriage baskets, and baskets for fruit, flowers, &c (Ballarat Star, 22/7/1869).

The women of Coranderrk ‘are not idle. They employ themselves in making baskets, nets; and bags, and many really useful and beautiful baskets are now on sale at Mr Reed’s fancy repository in Collins-street east. The baskets are made of the common coarse grass found growing in the swampy lands near Coranderrk. Some of them are elegant in form, and all of them are durable. Few more interesting presents could be sent to Europe. Mr Brough Smyth has kindly advertised the sale of these articles at his own expense, in order to encourage the native women to persevere with the work’ (Geelong Advertiser, 22/7/1869).

THE ABORIGINES.

In reference to the efforts that have been made to encourage the aborigines in industrial pursuits, and Mr. Reed, of the Fancy Repository in Collins-street, having undertaken to sell the baskets and nets which they manufacture free of cost, and without deduction of any kind, it is only proper to report that when the secretary of the Central Board for Aborigines visited the station a few days ago, and handed to the aborigines the several sums which they had earned by their industry, they testified in the most lively manner their appreciation of, the efforts made on their behalf, and promised to give the utmost attention to any hints for improvements in the form of the baskets, &c. About twenty-seven baskets were lately sent to Mr. Reed for sale. They are of various forms and sizes, and some of them are elegant, and all of them are neatly and strongly made (The Argus, 13/9/1869).

Brough Smyth (Victoria: 1871: 8) noted that:

There are few native weapons to be found now at Coranderrk. Not without some difficulty fire-sticks, and asked one of the men to make fire after the native fashion, in order that a sketch of him and his implements might be made. As showing how small must have been the intercourse amongst the Aborigines in the olden time, I may mention that whilst a southern black was engaged in this employment (twirling the upright stick), a Murray black – a recent arrival at the Coranderrk station – said that he could make fire much quicker and with less labor. Knowing the method he would employ, which is the same as that practised in many parts of New Zealand by the Maories, I asked him to set to work, and he did so, raising a smoke in a few seconds. This surprised the southern Aborigines, and they were not well pleased to see that one of their own race was somewhat in advance of them. The women spend the time they can spare from the cares of their households in making baskets, nets, and bags. The forms of the baskets are good, and since I made designs for them they have improved rapidly, and are now capable of fashioning quite intricate patterns.

2.9 R.H. Otter, 1872

In the early 1870s visitors’ accounts such as Otter (1872) and Craig (1873) confirm the consolidation of the tourist economy at Coranderrk that emerged in the 1860s in which residents made artefacts and handicrafts for the emerging tourist trade. Robert Henry Otter visited Australia in late 1872 on advice from his physician to spend the English winter abroad on account of his invalidism.8 He travelled with his brother and a cousin and arrived in Melbourne on 13 December 1872 on the Renown – Green’s Blackwell Liner.9 In his publication, Otter (1882: 15) reveals that he remained a month in Melbourne from 14 December 1872 to 15 January 1873 and spent a further week in February 1874. In the preface to his publication, he explained that the purpose of his book was to ‘give those who are advised by their doctors to spend their winters away from England on account of health, some information respecting the different places which I have myself visited for the same reason’. He wished to inform his readers of the easiest routes, the weather to be prepared for, and the occupations and amusements which the visited places afforded.

During his stay in Melbourne he visited Coranderrk as part of a five or six day excursion by buggy to ‘the black spur range of the Dandenong Mountains’. In his account of his visit he has overstated the number of residents – there were approximately 107 residents (Victoria, 1871: 3), not over 400.

On this expedition we visited a place called Healesville, where the Colonial Government has established one of its reserves for the small remnant of the aboriginal inhabitants which is still left in the Colony. There are between 400 and 500 of these natives gathered together and living in huts round the house of the Government Superintendent. There is a school for the children, and every effort is made to teach both young and old the way to get their living by husbandry and simple handicraft.10 From what I could hear, however, the natives do not seem to take to civilised ways, and it seems probable that they will soon become extinct, except in those parts of Australia which are still uncolonised by white men (Otter, 1882: 19–20).

From Melbourne, Otter visited Hobart, Sydney, Wollongong, the Blue Mountains, Bathurst, Goulburn, Brisbane, Maryborough, the Darling Downs, and the Riverina and Wagga Wagga, yet his visit to Coranderrk was the only time he met with Aboriginal people.

The Spectator (19/8/1882) considered Otter’s book furnished ‘a comprehensive account of the Australian Colonies seen from the point of view of the health-seeker, and contain, among other interesting details, a very charming account of life upon the Stations’.

2.10 James Whitelaw Craig, March 1875

James Whitelaw Craig (22/3/1849–16/9/1880) was an engineer by training, from Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland, but his passion was natural history. In 1873 his health deteriorated and he was encouraged to travel overseas in an attempt at regaining his health. He spent two years in Australia from November 1874 until November 1876 collecting specimens of birds, insects, butterflies and plants which he later presented to the Paisley Museum. His book Diary of a naturalist: being the record of three years’ work collecting specimens in the south of France and Australia, 1873–1877, was published posthumously in 1908 for private circulation. It was edited by his brother, A.F. Craig, who explains that his brother’s diary was discovered some 28 years after his death and as it was found difficult to discriminate as to what should be left out and what should remain’ ‘it was decided to print the whole’.

Craig visited Healesville on Monday 1 March 1875 and went to Coranderrk:

Left Melbourne at 8 o’clock this morning for Healesville. Arrived at 2.30 p.m. Very hot day. Visited the Black Station, which is about two miles from Healesville. Found most of the blacks busy picking hops. Measles had been very prevalent among them. Some deaths occurred, and some of the blacks were still suffering. This has been a very prevalent disease in Melbourne this summer. Got a few insects.

He returned to Coranderrk four days later on Friday 5 March:

Visited the Black Station in the afternoon. Spoke to two of the blacks, who told me that they were not compelled to remain at the station, but could leave when they liked, but preferred being there to knocking about. They are fed and clothed by Government, and some of them get 6/- a week when working full time. There hours are from nine till one, and from two till five. Saturday is a full holiday. There is a sewing school and a church in connection with the station. There are 130 blacks now at the station. Got a few insects to-day; also some native weapons, consisting of three boomerangs, one spear and wummerie (or spear thrower), a shield, and a waddy or club.

In the preface to the posthumous publication of his brother’s diary, A.F. Craig refers to ‘The Craig Collection of Australian Natural History’ that was presented to the Paisley Museum. This collection contains a large number of birds and animals, and insects, ‘as well as curiosities, such as the weapons used by the Australian Aborigines – spears, boomerangs, and such like’. In communications with Ms Nicola Macintyre, the Assistant Curator of Natural History, at Paisley Museum, I have learned that the Aboriginal objects in the Craig Collection were donated by A.F. Craig and their provenance is listed as Queensland. However, it is possible that this information was not attached to the objects when they were donated to the museum, but added later, so some of the objects may be from Victoria (N. Macintyre personal communication, 30/9/2014).

In relation to the Aboriginal people of Australia, A.F. Craig notes that his brother ‘made friends with some of the Aborigines of Australia; bought curiosities from them, studied their habits and language, and has given in his Diary a vocabulary of some of the words’ (Craig, 1908: 4). On a visit to Beenleigh on the Albert River, Craig sought out German missionary Johann Gottfried Haussman (1811–1901). Haussman had established the Bethesda mission in 1866 among the Yugambeh people. At The Gap, Craig asked one Aboriginal man if he could procure for him (Craig) the skull of a black fellow. Craig (1908: 171) recorded his response: ‘he was horrified at the idea, and said the black fellow (evidently meaning his spirit) would come after him’. Craig’s book includes three photographs of Queensland Aboriginal people – presumably they were taken by Craig during his stay in Australia.

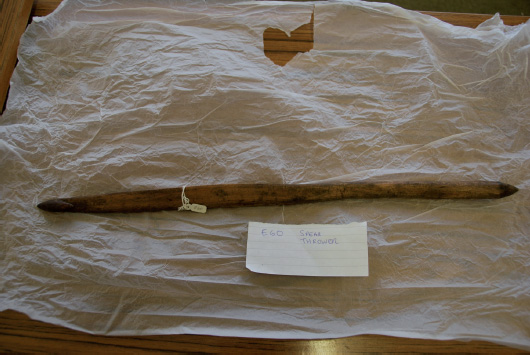

A.F. Craig in a footnote confirmed that the cultural materials his brother obtained at Sandgate ‘may be seen in the Paisley Museum’ (Craig, 1908: 110; 148, 150). A careful reading of Craig’s diary reveals that during his sojourn in Australia, Craig collected a stone tomahawk from Dromana; boomerangs, spear and spear thrower, shield and clubs from Coranderrk; a woman’s mourning headgear made from feathers, and a club and waddy from Sandgate; three boomerangs were purchased at Sandgate, along with a nulla-nulla and pieces of wood used for making fires and a different kind of morning badge worn in the hair; dilly bag from Brisbane; and a carving implement made from cheek bone of possum at The Gap (now a suburb of Brisbane), along with 230 words of vocabulary from Aboriginal people he met at The Gap in Queensland. Given that he collected boomerangs and clubs/nulla nulla from both Coranderrk and Sandgate it will be difficult to tell them apart if they have been incorrectly described. According to his diary, however, he only collected a spear and spear thrower and shield from Coranderrk and there is no indication that he collected examples of these anywhere else he visited (see Figures 2.2–2.7).

In terms of craftwork on the station, annual reports for the rest of the decade confirmed that the women continued to make baskets and table mats for which they received a ready sale and good prices (Victoria, 1874: 5).

2.11 Healesville in the 1880s

Symonds (1982: 61) has confirmed that with the greater leisure and prosperity of the 1880s, Healesville came into its own – in one eight day period in 1885 Cobb & Co. carried 1064 passengers to the three resort towns of Healesville, Fernshaw and Marysville. The railway from Lilydale to Healesville opened in March 1889 and that year overcrowding in hotels was such a problem that dining rooms, parlours, and sheds and stables were used as temporary sleeping quarters.

Diane Barwick (1998: 304) has reflected on the turbulence of the 1870s and 1880s:

The successful farming township which Green and the Kulin had built was destroyed in the 1880s by a handful of men who had rarely visited and never listened to the Kulin. The blackfellows’ township which had been a source of pride to the clan-heads Wonga and Barak became a shabby zoo where thousands of idle tourists visited on Sunday afternoons. They came for a ‘peep at the blacks’; they went away with their prejudices confirmed.

Ethel Shaw has detailed the daily rhythm of life on the Coranderrk station in the 1880s when her parents assumed responsibility for the station;

The day began with morning prayers. Men, women and children assembled in the church, a hymn was sung, followed by a brief reading from the Bible, a short talk, and a prayer to God for help and guidance through the day. After the service the men gathered near the bellpost for the day’s orders. Often there were matters to be talked over. Anything that had happened to disturb the harmony of the people, or a quarrel to be settled, was brought up, the “’pros and cons” discussed; often a little joke or friendly sarcasm from Mr. Shaw would provoke a hearty burst of laughter and restore peace. After the talk the men went to their allotted duties. There was regular work in the hop garden. The usual farm work to provide food for man and beast required a fair amount of labour. Paddocks had to be cleared, fences repaired, and a large herd of Herefords and Shorthorns to be looked after. All this provided work for many hands.

Figure 2.3: Aboriginal Shield in the Craig Collection, Paisley Museum.

Figure 2.5: Spear thrower in the Craig Collection, Paisley Museum.

Figure 2.7: Aboriginal club in the Craig Collection, Paisley Museum.

The women attended to their homes, and children. Some were good housekeepers, and took a pride in keeping their houses and children neat and clean. Mrs. Shaw inspected the houses once a week; marks were given for the best-kept house, and prizes awarded at the end of year. The women enjoyed these visits, and were ready with smiles of welcome. They loved to chat over things and any little trouble and problem was talked over and advice given. They made their own and children’s clothes. Mrs. Shaw held a sewing class for any who needed help, and also to make clothes for the old women. In their spare time the women made baskets, which found a ready sale to visitors. They had to go some distance to gather the right variety of rush. To prepare the rush for use, it was split from top to bottom with the thumb and first finger, the strands tied together in bundles, and then soaked in water for some hours. The bundles or hanks were hung up to dry; they were then ready for use. The old Aboriginal women began to make the basket by tieing three or four strands together and winding them around their big toes and working buttonholes stitch round the loops thus formed. The baskets were very firm and durable, and most attractive in appearance, particularly when decorated with a red rush worked in a pattern round the basket. This rush was rather scarce, so was only used as a decoration (Shaw, 1949: 16, 18).

Ethel Shaw (1949: 21) also explained how the Aboriginal residents would supplement the clothing they were provided with by the Government by purchasing extra materials from the money they received as wages or from the sales of weapons and baskets.

2.12 Hawkers at Coranderrk

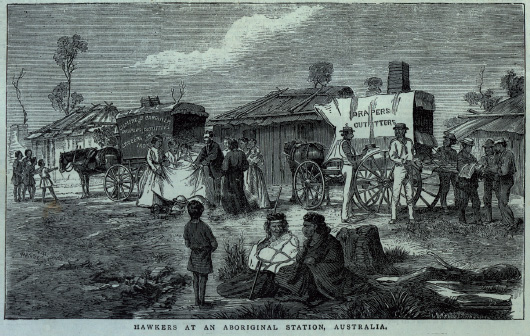

During the 1880s Indian hawkers and Chinese tinkers were welcome visitors at Coranderrk which was one of their ‘ports of call’. Ethel Shaw recalled that ‘a cheery welcome awaited “Joe, the hawker”. He knew well how to cater for his Aboriginal customers. Brightly-coloured materials for the women and bottles of scent and pomade for their hair were very popular among the belles and dandies of the community. “Jimmy the Chinaman” was also a favourite. With a bland smile wreathing his face, he soon disposed of his jars of preserved ginger, gaily-coloured silk handkerchiefs and sticks of lolly and liquorice. There was usually a ripple of amusement when “Charlie the crockery man” appeared with his quaint, old-fashioned van. He used to extol his wares by tapping them with his knuckles, assuring one and all that they were “very good china” (Shaw, 1949: 21) (see Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8: Hawkers at an Aboriginal Station, Australia (The Pictorial World, 14/10/1876: 112). The same image has been reproduced in the Illustrated Australian News (10/7/1876) with the title ‘Hawkers at the Aboriginal Station, Coranderrk. View from a photograph by F. Kruger, Preston’, where it has the following description: Scene observed by the artist afforded evidence of the extent of the progress of civilisation among the aborigines settled in that locality. Here we see one of these hawkers who perambulate the country with their vehicles, containing, as usual, a miscellaneous assortment of goods, engaged in offering his bargains to an assemblage of the youthful population of the aboriginal settlement. The interest taken by the mothers and maidens in the gown pieces offered for their inspection is manifest, and equally so is the pleasing prospect before the lads of becoming possessors of moleskins and billycocks which they appear to be handling like any expert in soft goods (Illustrated Australian News, 10/7/1876).

2.13 Garnet Walch’s Request for Information: ‘Visitors Not Refused But Not Invited’

In October 1886, Garnet Walch, editor of the Gem Guides wrote to the Secretary of the Board advising him that he was compiling a new ‘“Guide to Melbourne” and he was anxious to include particulars of Melbourne’s “remaining aborigines” and especially hints for intending visitors to “Coranderrk”, means of reaching locality – formalities to be observe in order to obtain permission to view’ (Lydon, 2005: 181). After a silence of a month, Walch sent a reminder. On this letter an official has noted ‘Doesn’t wish anything published as to best way of getting to Coranderrk – Visitors not refused but not invited’.

2.14 Massina’s 1888 Visitor Guide

In 1888 Massina and Co. published a visitors’ guide to the holiday destinations to the Upper Yarra and Fern Tree Gully districts. The guide sold for one shilling and contained 12 maps and detailed descriptions of the holiday destinations east of Melbourne. Aitken (2004: 51) in a study of early tourist guides in Victoria has confirmed it was published at the time the railway was being constructed between Ringwood and Fern Tree Gully and the Dandenongs were emerging as a recreational resort. The late nineteenth century was a time before the advent of the motor car completely changed the experience of tourism in the twentieth century. It was also the period before photography was widely available and guidebooks were often kept as mementoes of holidays and excursions. The guide is very clear that mementoes may be purchased at Coranderrk including possum skin rugs and fancy mats made from wallaby and koala skins:

Noticeable on the right hand, about a mile or so from the Yarra, is the entrance gate to the Coranderrk Station, for the remnant of aboriginals still existing. It is a large reserve of over 4000 acres, and during the long regime of Mr. Green, that gentleman introduced hop-growing as one of the industries of the place, and fairly tested the district for the growth of that crop. The place is now presided over by Mr. Shaw, who seems to have secured the good-will of the unfortunate people, who are fast being thinned by age and disease. A good deal of work is got though at times, the women being expert with the needle, and skilled in the manipulation, from indigenous vegetation, of basketware, nets, and other articles of an ornamental or useful nature. Visitors wishing to take away mementoes of their trip may purchase many articles of great interest as exhibiting the skill and patience of their fabricators. Opossum rugs and fancy mats of wallaby and bear skins are also to be purchased by those desiring such (Massina, 1888: 56).

Joseph Shaw (Victoria, 1889: 6) confirmed that the residents continued to ‘make a great deal of money during the summer months by making and selling baskets, and the money so earned is generally well laid out either in the purchasing of clothing, or furniture for their houses, and thus, they grow in habits of usefulness and industry’.

Edmonds and Clarke (2009: 15) have noted that by the end of the nineteenth century, Aboriginal material culture in south-east Australia had changed dramatically. New ways of drawing and painting remained secondary artistic practices compared to the manufacture and decoration of wooden and woven artefacts for trading with outsiders. They observe the irony that although Aboriginal people were being increasingly categorized and labelled according to their skin colour and their cultural practices were considered obsolete, they continued to fascinate the general public. They highlight how Coranderrk became a popular site for tourists who could purchase items perceived as traditional (that is, authentic and pre-contact) and view displays of boomerang throwing and listen to storytelling. They observe that William Barak (see Chapter 6) was one of those willing to share his culture with Europeans and they argue that it is possible that he and others on the station supported tourism as a means of ensuring the survival of their art practices as well as a potential way of persuading Europeans of the validity of their culture.

2.15 Healesville in the Early 1900s

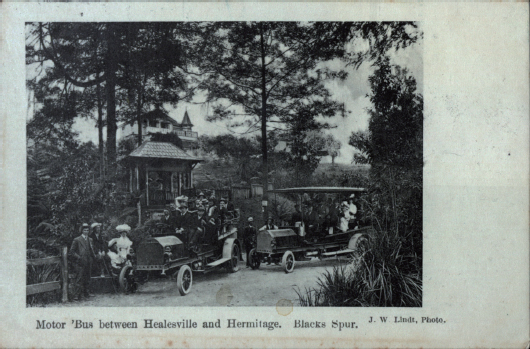

The advent of the motorcar in the early 1900s transformed tourism at Healesville. Henry Phillipe, an employee at Gracedale, a leading guesthouse, explained the nature of his work with visitors in the early 1900s:

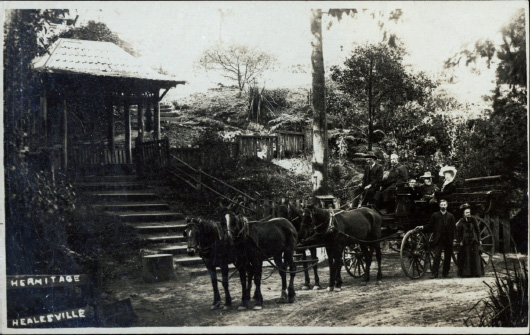

My work was to take people for day or half-day drives with horses and waggonettes. Maroondah Weir was one of the favourite drives. After coming to the weir the visitors would take a walk up the side of Mount Monda to see the Matthina Falls. Another half-day trip was to Coranderrk Aboriginal Reserve where the natives would race up to display their wares and their prowess with boomerangs and the firestick. When the fire blazed was the signal for the hat to go round. These trips were also done by other livery stables in Healesville. Mr Cornish worked in one season sixty horses daily – and then there were trains to meet, in and out, all day as well (Symonds, 1982: 79) (see Figures 2.10–2.12).

James Smith in The Cyclopedia of Victoria (1905 vol. 3:44) in a description of Healesville and district stated that ‘The aboriginal station at Coranderrk, the Graceburn and Maroondah weirs, and the Mathinna Falls are among the attractive features of the district more immediately surrounding Healesville’.

In the Companion Guide to Healesville … and other localities in the district, published in 1904 and written by N.J. Caire and J.W. Lindt, the preface indicates that its purpose is ‘to bring prominently before tourists and holiday seekers the beauties of the Mountain Scenery in the Healesville district’. Coranderrk is listed as one of the visitor attractions or ‘outings’ in the district and considered a place of interest within easy walking distance from Healesville:

Coranderrk: – An aboriginal station under the supervision of Rev. Mr. Shaw. Open to the public during the week, Sundays excepted. The natives make and sell the various implements used in war and chase, and are always ready to give exhibitions of boomerang and spear throwing; also fire making. They are christianised. Most are educated, and assist in raising hops. Distance from railway station entrance gates: 2½ miles (Caire & Lindt, 1904: 45).

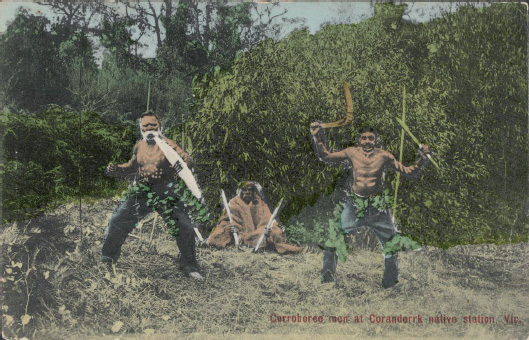

The guide contained the following ‘photographic note’ concerning Coranderrk: ‘The aboriginal station. Permission to photograph must be obtained (Caire & Lindt, 1904: 63). The guidebook published 65 illustrations including one scene from Coranderrk: ‘Type of Cooroboree Men at Coranderrk’ (see Figure 2.9). The image does not appear in later editions. The image was used as a popular postcard in the early 1900s but with a different caption.

Figure 2.9: Corroboree men at Coranderrk native station, Vic. Source: Author’s private collection. The three men (left to right) are: Lanky Manton; John Terrick; and Harry McRae.

Figure: 2.10: Black’s Spur, Healesville. (Author’s private collection).

Figure 2.11: Hermitage, Healesville. (c.1906–1910). J. Kercheval, Healesville, Victoria, Australia. (Author’s private collection).

Figure: 2.12: ‘Motor ‘Bus between Healesville and Hermitage. Blacks Spur’. J.W. Lindt. Photo. (c. 1910) (Author’s private collection).

2.16 Elinor Clowes and Coranderrk

Elinor M. Clowes (1911: 296–308) was another who had visited Coranderrk and recalled ‘the people all seemed exceedingly leisurely and good tempered, and childishly clamorous for pennies. Two or three men emulated each other in throwing the boomerang for our amusement’. Clowes noted that the ‘little huts at Coranderrk are tidy and comfortable, and the people well fed and cared for; but there is something inexpressibly sad about the whole encampment’.

Elinor May Clowes used the pseudonym ‘Elinor Mordaunt’. In 1898 she married Maurice Wilhemn Wiehe in Mauritius. In January 1933 she married Robert Rawnsley Bowles. Born in Nottinghamshire in May 1877, she arrived in Australia in 1902 and lived in Melbourne for seven and a half years (Mordaunt 1937: 121). For the next nine years she published semi-travel accounts of her experiences in Australia, including her 1911 publication On the Wallaby Through Victoria . In 1909 she returned to England, and in 1915 she changed her name by deed poll to Evelyn May Mordaunt. She died in June 1942 in Oxford.11 In the introduction to On the Wallaby … she notes she was ‘asked to write something about the country which has extended its hospitality to me … I can only write about Victoria as I know it. … my nose has been too close to the grindstone, while life has resolved itself for the most part into a mere struggle for existence. Still, that very struggle has brought me into touch with real people, and with the many grades of society which are to be found here as elsewhere, in spite of all the theories of democracy. I have edited a woman’s fashion paper, of sorts, … I have written short stories and articles; I have decorated houses, painted friezes, made blouses for tea-room girls, designed embroideries for the elect of Toorak, even for the sacred denizens of Government House. I have housekept, washed, ironed, cooked. Once I made a garden … (Clowes, 1911: v-vii).

In the final chapter of On the Wallaby Through Victoria which is entitled ‘Primitive Victoria’, she devotes 13 pages to discussing Aboriginal people. She begins this discussion with reference to Coranderrk.

About a couple of hours’ journey from Melbourne, and within a short drive from Healesville, there is a Blacks’ Settlement, where there is gathered together a remnant of those people who, with their four-footed fellows, were once in undisputed possession of these mountains and forests—before the days of the axe and saw, the “stump-jump,” and the “mallee roller.”

It is a good many years since I was at Coranderrk, as the settlement is named, and therefore I have no very clear memories of it, excepting that the people all seemed exceedingly leisurely and good tempered, and childishly clamorous for pennies. Two or three men emulated each other in throwing the boomerang for our amusement, and in this the older men were certainly by far the best, literally bursting with pride at their achievements; one grey-haired man, taller and bigger-built than his fellows, sending it to such a height and distance that it had dwindled to a hardly distinguishable speck against the blue sky before it turned and came whistling back, in a sweeping semicircle, to drop almost exactly at the place where its owner stood.

The little huts at Coranderrk are tidy and comfortable, and the people well fed and cared for; but there is something inexpressibly sad about the whole encampment. It is bad enough to see one person dying—say of consumption, or some such fatal disease—but it is worse by far to see a whole people die, no matter how ineffectual they may be in their powers of grappling with the conditions of modern life, for those individuals who are not actually dead are yet in a state of senile decay, and, having lost the wonderful instincts of a savage, are still groping wistfully and ignorantly among the intricate ways of civilization. Still, sometimes if you can borrow a black fellow, to go fishing or trapping with, you may yet catch sight of a spark of the old bushman’s cunning and mysterious lore.

2.17 Officers from the American Fleet 1908

On 4 September 1908, 160 officers of the American fleet were guests of the Melbourne Automobile Club. Seventy cars made their way to Gracedale where they were entertained to lunch and amusements including boomerang throwing demonstrations (Symonds, 1982: 92). At a public meeting, convened by the shire president, in late July, to make arrangements for welcoming the officers of the American fleet on a trip to Fernshaw on 4th September it was decided upon a suggestion from the Automobile Club to have a demonstration of spear and boomerang throwing by the Coranderrk aborigines, and wood chopping contests-standing block and underhand (Healesville & Yarra Glen Guardian, 24/7/1908). The local paper ran the following story of the event:

THE FLEET OFFICERS. HEALESVILLE’S WELCOME. A BIG DISPLAY.

Local residents were early astir this morning in anticipation of the visit, as guests of the Melbourne Automobile Club, of over 100 officers of the American fleet. ... There were altogether 70 cars. They were given an enthusiastic ovation as they passed along the street en route for Fernshaw and Gracedale House, where they were to be entertained at lunch and to witness a programme of wood chopping contests and Coranderrk aboriginals making fire and throwing boomerangs and spears, That portion of the days entertainment was proceeding as we went to press. ... Several modern camera friends were present to take moving pictures of the proceedings (Healesville & Yarra Glen Guardian, 4/9/1908).

2.18 The Gift of Boomerangs, October 1909

Boomerangs made by the Coranderrk residents were given as gifts in October 1909. The occasion was a meeting of the Melbourne Chamber of Commerce and each delegate was presented with a Coranderrk boomerang. Accompanying each boomerang was the following letter:

We hand you a real Australian boomerang made by Australian blacks, and we trust you will accept this as a souvenir of your visit to Victoria. As the main feature of the boomerang is that it returns again to its thrower we hope you will recognise in this small gift the symbol of our wish that you will return again to Australia (The Argus, 4/10/1909).

Kleinert (2012: 93) has discussed how boomerangs came to represent a symbol of Australian identity; for Aboriginal people it was a critical part of their heritage, and boomerang throwing became a staged ‘spectacle of Aboriginality’ – one that everyone enjoyed.

2.19 The Companion Guide to Healesville

The Companion Guide to Healesville, Blacks’ Spur, Narbethng, Marysville, Mt Donnabuang, Ben Cairn, and The Taggerty, published in 1916,12 updated information presented in the first edition in 1904 (see above).

Coranderrk Aboriginal Mission Station.

Among the five or six stations set apart by the Victorian Government as homes for the aboriginal natives of this State, Coranderrk is perhaps the most important, supporting the largest community to be found on any of the Native Mission Stations. The well being of a native community depends largely on the organising capabilities of the manager in charge. The Rev. J. Shaw, who died some three years ago, during his long tenure of the position of Superintendent at Coranderrk proved what firmness and kindness will do in establishing, as it were, a social circle of the original sons and daughters of the Australian soil

Mr. Shaw’s place was taken, after an “interregnum,” by Mr. Chas. Robarts, whose wife acts as matron. The policy of match-making between the full-blooded blacks has been the occasion of several picturesque weddings during Mr Robarts’ term of office, and numerous little children about the Station prove very attractive to visitors.

The daily routine at the Station works like a clock. At 7 a.m. rations are served out. At 9 a.m. the bell rings, and is the daily ca1l to morning prayers. The call is not a compulsory one, as all are free to avail themselves of the benefits of the pastor’s spiritual services. Comfortable houses are provided for the numerous families, and these are gradually furnished and improved by the individual efforts of the various members of the community, as they occupy a great deal of their time in making weapons, such as spears, waddies, boomerangs, shields, etc., which they dispose of to the numerous visitors who call at the station.

The station is not by any means regarded as a show place, but the genial Superintendent is always pleased to grant permission for visitors to see around the place on their applying to him. Sunday is regarded as a day of rest, all work being suspended, and the usual church services are held in the building used for that purpose.

Coranderrk is listed as one of the visitor attractions or ‘outings’ in the district and considered a place of interest within easy walking distance from Healesville:

Coranderrk: – An aboriginal station under the supervision of Mr. and Mrs. Chas. Robarts. Open to the public every day. The natives make and sell the various implements used in war and chase, and are always ready to give exhibitions of boomerang and spear throwing; also fire making. They are Christianised. Most are educated, and their chief employment is cattle breeding. Fishing and the sale of weapons and baskets engage their attention at odd times. Distance from railway station entrance gates: 2½ miles.

The guide contained the following ‘photographic note’ concerning Coranderrk: ‘The aboriginal station. Permission to photograph is not now necessary except from the natives concerned. Any promise of photographs to them should be faithfully kept, or an equivalent sent, as they feel greatly offended with those who do not fulfil their promise.

Massola (1975: 41) asserts that ‘Sundays and holidays were “open days” and visitors came to the station to look around and, if they wished, could buy “curios” from the natives’, but Maurice Robarts in his reminiscences was clear that Saturdays were ‘open days’ (Clark 2014b: 220):

For two successive winters about 1911–12 we had a Coranderrk football team (all coloured) cheered on lustily by the whole settlement, & Badger Creek community; their pleasure in the sport won them the premiership of the Yarra Valley Association in the second season. It is rather amusing to recall that a popular position amongst the older men in late summer afternoon was playing marbles & they were really good. Many of the older women made baskets, from rushes grown on the Yarra river flats, these were always saleable to visitors to the station, permitted on Saturdays & driven out from Healesville by wagonette or cab. Fishing was good in both the Badger & Yarra. Making of Aboriginal weapons & curios for sale was a popular occupation (Clark, 2014b: 220).

2.20 Raffia Work, 1909

In 1909 the women’s basket work at Coranderrk underwent a transformation as they began to learn raffia work. The matron of Coranderrk, Natalie Robarts, first discussed this in her diary:

On Wednesdays, her ‘day off’, Mrs Robarts went to Lilydale for a lesson on raffia work, which she was learning from a Miss Hynes, who was later employed for some time as governess to the Robarts’ children. Mrs Robarts obtained permission from the Board to teach raffia work to the Coranderrk women they seem quite interested in it and are looking forward to their lessons (Robarts diary 14/7/1909 in Clark, 2014b: 34f).

Two months later she noted ‘We had quite a little pleasant disturbance, Mr. Fisk13 the photographer came to take several photos of the natives, and I proposed he should take the women at Raffia work, & so he did ...’ (Robarts diary 8/9/1909 in Clark, 2014b: 38). The new industry was local news:

A New Industry at Coranderrk.

Mr and Mrs Robarts, managers at Coranderrk station, are to be congratulated on their introduction of an industry that promises to be of more than ordinary interest and importance. Raffia work is becoming very popular in its varied forms of belts and baskets, bats and other articles of use and ornament. The pliable fibre is admirably adapted to the dexterous manipulation for which our Coranderrk workers are so famed, and already, many samples of their work may be seen at the station. At the same time it need not be feared that the more characteristic green rush work for which our natives have so far been known will suffer by this new industry. At certain seasons of the year, the green rush is not obtainable; for instance, it is just now very scarce, whereas Raffia fibre is always on the market, and will be used when the green rush is hard to get. In this way Coranderrk visitors will be less rarely disappointed in their desire to secure momentoes [sic] of their visit. To watch the nimble native fingers at work fashioning these articles is quite a treat, the women being notable for their slim and shapely hands. They are being trained at present by Miss Hyne, governess to Mrs Robarts’ children, who now resides at the station, having left her former residence at Lilydale. Miss Hyne learnt Raffia work in America, where it is “all the rage,” and she was until a while ago one of the most sought after teachers of this work in Melbourne. With so able a teacher and such apt pupils Coranderrk should soon become notable for its Raffia work (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 17/9/1909).

Natalie Robarts diarized the first sales: ‘The first Raffia work was sold last week, Violet sold her belt for 1/6 & she is working another which is ordered. Eliza Fenton also disposed of her first belt & Miss Hyne of a basket, all looks encouraging’ (Robarts diary 9/10/1909 in Clark, 2014b: 40). The Board would later report that ‘The introduction of the Raffia basket-making has been very successful; a number of the women make these baskets and find ready sale for them’ (Victoria, 1911: 5f).

2.21 South African Cricket Team, February 1911

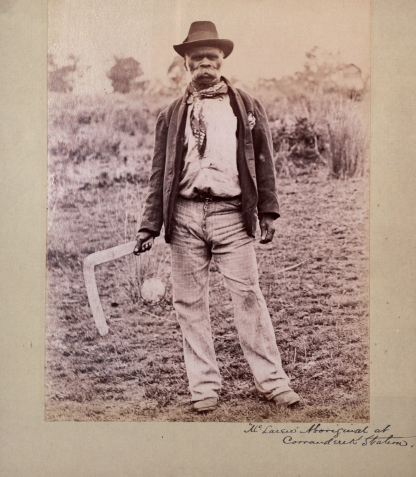

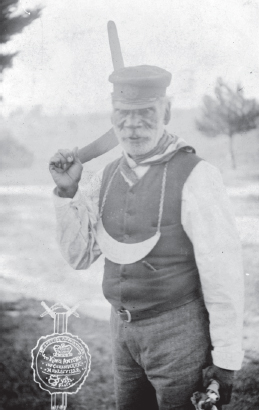

In February 1911, several players from the South African cricket team were visiting Healesville and they were entertained by several Aboriginal men from Coranderrk who demonstrated boomerang-throwing and fire-making (see Figure 2.13). Both The Argus and the local Healesville paper published accounts of the visit

Figure 2.13: ‘McLaren Aboriginal at Corranderrk Station’ (Author’s picture collection). The State Library of Victoria has a photograph entitled King Billy & a Mate, Coranderrk Station’ (see Figure 6.1) which contains William Barak standing with this man on his left. According to the SLV catalogue entry the photographer is W.H. Ferguson.

BATSMEN AND BOOMERANGS.

Healesville Thursday – A number of the South African cricketers who visited Healesville by motor car yesterday were entertained by boomerang-throwing and fire-making by several aborigines from Coranderrk. Enamoured of the possibilities of the Australian boomerang, which to them appeared a more puzzling weapon than the assegai of their native land, the cricketers insisted on being allowed to learn how to throw it. The result was that a large number of spectators were attracted by the unusual sight of six well-dressed young men, and a portly gentleman of more mature years madly throwing boomerangs in the main street. So delighted were the members of the team with their swiftly acquired proficiency that each left Healesville with a boomerang as a souvenir (The Argus, 17/2/1911).

The South African cricketers had a trip from Melbourne to the Black Spur by motors last week. Several of the aborigines from Coranderrk, who happened to be in the town at the time, gave an exhibition of boomerang throwing and also their method of lighting fires. For about an hour boomerangs were flying about all over the place, and before the motors departed many of the South Africans had become quite adept at throwing these ancient weapons. The visitors evidently enjoyed the unique exhibition, considering the way in which they purchased boomerangs from the makers, and no doubt the gentlemen from Coranderrk would like the visitors to pay many such visits to Healesville (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 24/2/1911).

Symonds (1982: 94) has noted that in ‘1911 tourists flocked to Healesville and it became known as the premier tourist resort in the State. Christmas was described as the best ever experienced and even at Easter 10,000 visited the town, 5,000 of them by train’.

2.22 Temptations in the Tourist Resort of Healesville, 1911

In his annual report for 1911, Charles Robarts reported that he had some concern with the proximity of Coranderrk to the tourist resort of Healesville – he considered that alcohol was too readily available to the men:

The conduct of the people on the whole has been fair. This Station being only 3 miles from the township of Healesville, which, being a tourist resort, offers attractions to which the natives are so easily drawn. The women and children are satisfied with the picture shows, &c, but the men who can and will get drink, by the help of the outside half-castes who do not come under the Aborigines Restriction Act, often give me a deal of trouble (Victoria, 1912: 5f)

2.23 Healesville Shire Council: Coranderrk ‘Will Ruin Healesville as a Tourist Resort’

In 1914 and 1915 Healesville residents petitioned the government to resume the Coranderrk reserve for a permanent military camp. The Healesville Shire Council organized a public protest meeting asserting that ‘the congregation of a degenerate race a few miles from the township will ruin Healesville as a tourist resort’ (Barwick 1998: 306–7). This was a ridiculous claim given that Coranderrk was a staple for the tourism industry in Healesville and the townsfolk had been ‘touting tours of Coranderrk as a major tourist attraction for decades’ (Barwick, 1898: 307). Barwick (1998: 307) asserts that in the post war years some 2,000 visitors went to Coranderrk every year.

2.24 Rev. Frederic Chambers Spurr – Impressions and Experiences of Coranderrk

In 1915 Rev. Frederic Chambers Spurr, minister of the First Baptist Church in Melbourne from 1909–1914, published an account of his experiences and impressions in Australia – entitled Five years under the Southern Cross: experiences and impressions (see Appendix 2.1). It included his observations of Coranderrk. In the preface to the work, Spurr explained that much of it was based on a large number of articles on life in the Commonwealth he had written for the English periodical Christian World. Spurr had succeeded Rev. S. Pearce Carey as Minister at the Collins-St Baptist Church in May 1909. He had begun his clerical career in Wales and was at one time special missionary for the Baptist Union of Great Britain. Before coming to Melbourne he was pastor of Maze Pond Church, London. An earlier ministry was at Cardiff. In early 1914 he returned to London where he succeeded Rev. Frederick Mayer as minister of the Regent’s Park Chapel, London (The Advertiser, 1/5/1914).

The book was reviewed in the Euroa Advertiser (21/5/1915)

A Poor King.

Hardly less entertaining are the author’s observations regarding the aborigines. Almost every district in the State has had its Billy – a last lone aboriginal to whom somebody or other gave a brass plate bearing a royal inscription. These derelicts of the black race were only small boys at the time of the great inrush of the white population. Their ‘kinship’ was a joke. According to many authorities, the Victorian blacks had no ‘kings,’ or any ‘chiefs’; their tribal organisation was on a different plan. Mr. Spurr found a colored identity who had a plate bearing the words ‘King of Birchup,’ and he reflects upon the last state of the mighty fallen with moving pathos.

Native Cricket.

We read further on that when playing cricket,” the Coranderrk aborigines used as a bat ‘part of a boomerang.’ The author does not say whether there was any big hitting. He discovered, too, that when an aborigine throws a boomerang it ‘whistles and sings.’

2.25 Communal Sharing of Blankets, 1919

Management’s concerns with the eradication of some aspects of Aboriginal culture were still a reality as late as 1919, five years before the break up of Coranderrk. In a letter to the Board, the manager, Charles Robarts, hinted at a specific way in which the Aboriginal residents were maintaining their traditional practice of communal sharing. The issue concerned the annual issue of blankets – the manager reported that he did not order any blankets in 1918 as he ‘found by looking into each family’s supply they had sufficient. Out of habit and custom, the natives asked for the blankets, had they been presented, they would either have been given to outside families or exchanged for some inferior article, or even ... for erecting shelters when camping by the river’ (Robarts 16/1/1919 in Land, 2006: 192). Land’s (2006: 192) analysis is that the policy of providing clothes on an individual basis was being used by Robarts to try to curtail communal sharing of resources and to reduce the availability of blankets to be used for shelter on river sorties.

2.26 Tourism in the 1920s – Before the Closure of Coranderrk

Lydon (2005: 212) has noted that from 1918–20, the Blacks’ Spur Motor Service Garage took daily ‘pleasure drives’ to Coranderrk for a fee of two and a half shillings. Charles Robarts, the station manager, reported in July 1921 that tourism traffic at Coranderrk had increased, and estimated that some 2,000 visitors had been to the station during the past year which demanded that he constantly repair the road and build new fences (Lydon, 2005: 212). This popularity is confirmed by an article in The Argus (24/1/1922) which detailed the attractions in the Healesville district and considered ‘ One of the most interesting Saturday half-day trips is to Coranderrk aboriginal station, three miles from Healesville’. Lydon (2005: 177) has argued that a visit to Coranderrk ‘became a popular way to spend a day off, and by 1921, approximately four thousand visitors passed through every year, with hundreds arriving on Christmas Day and other public holidays’.

2.27 Mrs Aeneas Gunn, Coranderrk, and John Terrick

Jeannie Gunn lived at Elsey station on the Roper River, south of Darwin for 13 months before the untimely death of her husband saw her return to Victoria and live with her father at Monbulk. At Elsey she had taken a keen interest in the Aboriginal people on the station, and once back in Melbourne they became the focus of two publications: The Little Black Princess (1905) and We of the Never Never (1908). Presumably the interest in Aboriginal people that had been kindled at Elsey was continued at Coranderrk, some 35 km to the northeast. For example, Natalie Robarts noted in her diary for 22/2/1917, that ‘Mrs. Gunn (Mrs Aeneas Gunn, authoress of A Little Black Princess ) is with us since two weeks (Robarts diary 22/2/1917 in Clark, 2014b: 61). At Coranderrk she took a particular interest in John Terrick.

Margaret Berry, Jeannie Gunn’s niece, has written the following in her Memoir of Jeannie Gunn :

Jeannie returned to Australia in October 1913, as she felt she needed the ‘influence of the local environment’, the scent and sounds of the bush. She continued to work on The Making of Monbulk [which she’d begun in 1910] but, perhaps feeling more attuned to writing about the Aborigines, in 1917 she started to write another book to be called Terrick: His Book . She had focussed her attention on the Coranderrk Settlement near Healesville, in the hope of recording the habits and customs of the tribe there.

Terrick was the head of the tribe, and she would talk to him and try to elicit from him the information she wanted. He showed her his way of making fire, for instance, which differed from the way of the Elsey blacks. But he was old by then and there wasn’t enough time left for her to find out all she wanted to know. This book never passed the stage of rough notes. Another one of the blacks there, Lanky, taught her how to throw a boomerang and make it come back.

I always knew when she was going to Coranderrk because she would come home with yards and yards of flimsy blue gossamer material, which she would make into squares to give to the women of the tribe. They preferred blue. ‘It goes with our dark skins’, they said. They often gave her baskets they had made.

John Terrick died in June 1921. Natalie Robarts recorded his death and funeral:

I did not record the death of John Terrick, who just went out like a candle, there was no grumbling, but always real courtesy was shown a polite “thank you mam”.14 Mrs Gunn & Mr McAlister came to his funeral owing to the slowness of the coffin makers & the short winter days, when we left the church it was dusk. How it all seemed fitting with the hills all around us, the dead being placed in a dray which rumbled softly on the grass. The horse plodded to the Cemetery Hill amongst gum trees followed by all the people of the station. Mrs Gunn wished to accompany her old friend to his last destination (Robarts diary 23/6/1921 in Clark, 2014b: 85).15

In 1953, Oswald Robarts, Natalie Robarts’s journalist son, used his mother’s diary to memorialise the death of John Terrick and discussed his relationship with Mrs Gunn:

LAST VICTORIAN CHIEFS REST IN OBSCURITY

When the matron of Coranderrk Aboriginal Station recorded the death of John Terrick in the winter of 1921, she wrote of his last illness: “There was no grumbling; always a polite “thank you ma’am,” for every small attention.” Son of one of Victoria’s last aboriginal chiefs, John Terrick had come originally from the Terricks whose tribal domain lay to the north of the State. He was one of the few at Coranderrk Station who, as a youth, had been initiated according to tribal law. To-day he lies buried in an area the Queen will visit when in Victoria next year. – By O.C.R.

John Terrick was tall, slim and erect, courteous and quietly reserved. He had always been kind to the sick and to little children, though, as a true aborigine, it might be said that he had definite views on the place of women in the home or on walkabout. As one of the older generation of aborigines his loss was keenly felt by others on the station.

At intervals for more than two years before Terrick’s death Mrs. Aeneas Gunn had stayed at Coranderrk. She spent much time with Terrick and his wife Ellen on their rambles by the Badger River and the Yarra, gathering from his material on aboriginal legends and tribal lore. Already time had sealed the door on much that was gone forever. Research failed to provide sufficient additional material and a projected work, tentatively titled “Terrick – His Book,” was reluctantly laid aside. Australian aboriginal history is thereby the poorer.

But when John Terrick died the little “Missus” of Ealey station – of “We of the Never Never” – had not forgotten. She came specially from Melbourne to be present at the service on that late winter afternoon in the little wooden church at Coranderrk. Afterward, with dusk closing in a procession followed on foot behind Terrick’s coffin, winding slowly past the venerable pines and old hop kilns. It crossed s little Bridge and ascended to the cemetery among the gum trees on a knoll which looks westward across the Yarra flats to Steel Range and eastward toward Mounts Riddell and Toole-be-wong (Turm-be-waang). By her own wish Mrs. Gunn had taken her place in that silent cortege. After the burial service, read by the manager of the station, Terrick was laid to rest not far from William Barak, who had been the last chief and last surviving member of the Yarra Yarra tribe. Nearby were others who also occupy a special place in the early story of Victoria (Cairns Post, 28/12/1953)16

2.28 Dame Nellie Melba and Coranderrk

Dame Nellie Melba was another famous ‘local’ with a strong connection to Coranderrk.