4 International Dignitaries and Their Impressions of Coranderrk

Coranderrk was the site of many visits from international dignitaries, including royalty, and members of the political elite. This chapter looks at 14 of these visitors as diverse as media baron Lord Northcliffe to acclaimed English historian James Froude. Unfortunately we do not have details of the nature of every visit – in some cases we just have a matter-of-fact newspaper account that a visit took place. In other cases we have both newspaper accounts and published accounts from the dignitary. Where we have some detail we are able to reconstruct the performances the Coranderrk residents arranged for the visitors. Typically, these performances included boomerang throwing, spear throwing, and fire making. On some occasions the visitors were given gifts of baskets and clubs. On one very special occasion the visiting party was given a specially-made basket and some nicely carved emu eggs as gifts for the Queen. When the Victorian Governor Lord Brassey visited Coranderrk in late 1897, William Barak presented him with a picture of a corroboree painted in black on yellow on a slab of wood about 3 ft long by 2 ft high. When the new Anglican Bishop of Melbourne visited in October 1904 the Coranderrk people performed a corroboree with singing. In June 1910, artist Hugh Fisher of the Visual Instruction Committee of the Colonial Office visited Coranderrk to collect information and photographs and make paintings to be used in the preparation of educational lectures on Australia. At Coranderrk Fisher made a sketch of Anthony Anderson. Fisher’s personal diary of his visit is published here for the first time. In 1912 the Governor General Lord Denman visited Healesville as part of a special planting ceremony of oaks especially sent from the Queen. The Coranderrk residents participated in the celebrations, and other than boomerang throwing and fire lighting they presented Lord Denman with an ornamental boomerang with gold inscription plate, and Lady Denman with a native basket.

4.1 Sir William Henry Gregory, Former Governor of Ceylon, February 1877

One of the first international dignitaries to take ‘a peep’ at Coranderrk was Sir William Henry Gregory (1817–1892), an Anglo-Irish writer and politician. The South Australian Register, (22/2/1877) described him as ‘an archaeologist of acknowledged reputation’. He was appointed Governor of Ceylon in 1872. He resigned in 1877 and visited Australia en route to England. The Hobart Mercury (8/1/1877) announced his intention to visit NSW Governor, Sir Hercules Robinson, in Sydney, and stated that he would probably be ‘taking a peep in passing at the other Australian colonies’.66 The Argus (26/2/1877) reported that Sir William made an overnight visit to the Yarra Ranges, visiting Steavenson Falls and Marysville, and ‘on the way back made a short stay at the Aboriginal station, Coranderrk, where the natives were busily engaged in hop picking’.67 He returned to Melbourne tired but much pleased with his excursion.

4.2 James Anthony Froude, February 1885

James Anthony Froude (1818–1894), an English historian and biographer, visited Australia from January to February 1885 (see Figure 4.1). He spent three weeks in Victoria and travelled with his son Ashley Anthony Froude (1863–1949) and William Elphinstone (1828–1893), 15th Lord Elphinstone, who kept a portfolio of sketches, which Froude used when he published Oceana, his account of his travels. In the preface to this work, Froude (1886: iii) explained that the ‘object of my voyage was not only to see the Colonies themselves, but to hear the views of all classes of people there on the subject in which I was principally interested’. He spent four weeks in Victoria which included a stay at Mt. Macedon and tours of the Ballarat and Bendigo gold districts. The Argus (21/1/1885) considered he ‘is the most eminent man of letters that has ever visited our shores’. Blainey (1985: v) agreed: ‘He was probably the most famous intellectual to come to Britain’s southern colonies in the second half of the nineteenth century’.

In early February 1885, the Governor of Victoria Sir Henry Loch accompanied Froude, his party, and Sir George Verdon on a tour of the Healesville district. They visited Coranderrk ‘where the Blacks gave the visitors a treat in some boomerang throwing ( Evelyn Observer and South and East Bourke Record, 13/2/1885)’.68 The Australasian (7/2/1885) reported on the Coranderrk visit:

While sojourning in the Upper Yarra district His Excellency, with Lord Elphinstone and Mr. Froude, the historian, was the guest of Mr. H. de Castella, at St Hubert’s vineyard. On Wednesday the party were driven through Healesville and Fernshaw to the Black Spur in a special coach … On the return journey they called at Coranderrk, and saw an exhibition of boomerang-throwing by the blacks.

Froude (1886: 128) alluded to the visit in Oceana . Froude was visiting de Castella’s St Hubert vineyards near Healesville:

On the way home we turned aside to see a native settlement – a native school, &c. – very hopeless, but the best that could be done for a dying race. The poor creatures were clothed, but not in their right minds, if minds they had ever possessed. The faces of the children were hardly superior to those of apes, and showed less life and vigour. The men threw boomerangs and lances for us, but could not do it well. The manliness of the wild state had gone out of them, and nothing had come in its place or could come. One old fellow had been a chief in the district when Mr Castella first came to settle there. It was pathetic to see the affection which they still felt for each other in their changed relations.

Blainey’s (1985: 67) annotation of this passage in his abridged edition is that ‘Froude’s harsh, rather Darwinian, comment was typical of the era. The old Aboriginal whom Hubert de Castella greeted warmly was almost certainly William Barak (1824–1903), born before the British arrived’. Froude’s visit to Coranderrk was his only encounter with Australian Indigenous people. Later in New Zealand in an entry on the Maori he would write: ‘The Maori, like every other aboriginal people with whom we have come in contact, learn our vices faster than our virtues. They have been ruined physically, they have been demoralised in character, by drink’ (Froude, 1886: 223) – yet although he considered them ‘a sad, shameful, and miserable spectacle’ at Rotorua, they were ‘the noblest of the savage races with whom we have ever been brought in contact’ (Froude, 1886: 233). ‘Those only will survive who can domesticate themselves into servants of the modern forms of social development. … The negro submits to the conditions, becomes useful, and rises to a higher level. The Red Indian and the Maori pine away as in a cage, sink first into apathy and moral degradation, and then vanish’ (Froude 1886: 257–8).

Froude’s view of non-Anglo-Saxon races was that they were inferior and infantile. In contrast Anglo-Saxons ‘possessed superior physical and moral virtue and Froude never doubted their right to subjugate other peoples; in fact, the subjugation of other races became something of an obligation’ (Thompson, 1987: 210). British rule for subject races was for their own good, and if necessary should be imposed through military force – but Froude did not condone genocide. Thompson (1987: 4) stresses that a nuanced understanding of Froude’s racial chauvinism is necessary, for he never ruled out the possibility that given the time and opportunity other races might attain a moral and intellectual level equal to the Anglo-Saxon – suggesting the inherent equality of races rather than their inherent inferiority.

Froude has largely been ignored in the historiography of Coranderrk. John Stanley James, aka The Vagabond, when discussing Healesville, is one of the very few who has referred to his visit (The Australasian, 30/5/1885).

4.3 The Marquis and Marchioness of Stafford, Viscount Tarbat, November 1886

The Marquis and Marchioness of Stafford, and Viscount Tarbat visited Coranderrk on 30 November 1886.69 The Marquis of Stafford (Cromartie Sutherland-Leveson-Gower) (20/7/1851–27/6/1913), was a London-born Peer and politician, educated at Eton.70 His spouse, the Marchioness of Stafford (Lady Millicent Fanny St Clair-Erskine) (20/10/1867 – 20/8/1955) (they married on 20/10/1884 when Lady Erskine was 17 years of age) was a society hostess, social reformer, author, journalist, and playwright and often used the pseudonym ‘Erskine Gower’ (Freeman’s Journal, 14/12/1901) (see Figure 4.2). Viscount Tarbat (Francis Mackenzie Sutherland-Leveson-Gower) (3/8/1852–24/11/1893), the Second Earl of Cromartie, was the younger brother of the Marquis of Stafford. They arrived in Melbourne on 20 November and were guests of Victorian Governor Henry Brougham Loch. They were taken on excursions to Mt Macedon, Marysville, Fernshaw, and Healesville where they visited Coranderrk. The Argus (29/11/1886) announced their proposed visit to Healesville.

Marchioness Stafford (Millicent Stafford) published an account of her travels in 1889 entitled How I spent my Twentieth Year Being a Short Record of a Tour Round the World 1886–87 . In the preface she explained that her ‘notes were hastily jotted down as we journeyed from place to place, I had no intention whatever that they should be read by any but my immediate relations and friends. I have, however, complied with their wish that I should offer this journal to public criticism’. She noted ‘Those who have travelled will know how hard it is to find time for writing and sketching, and how difficult to form opinions on sights and events that, like a constantly changing kaleidoscope, continually pass before one, leaving but a faint impression’. She wrote the following concerning her visit to Coranderrk on 30 November 1886. Stafford expressed some disappointment that the Aboriginal residents were dressed like Europeans – she had expected them to be dressed more exotically. She noticed that in terms of their receptivity that they ‘seemed pleased to be visited’.

After passing Healesville we turned off to a native settlement which was most interesting. About ninety aborigines and half-castes are settled on a tract of land, with a European and Christian superintendent and schoolmaster. The school was full of little dusky children learning the three R’s; they were very well-mannered. All speak English, and rather to my disappointment were dressed in jackets and trousers like anybody else! The women are dreadfully ugly, but most pea- ceable and docile, and seemed pleased to be visited. The men threw boomerangs for us, and one of the old chiefs ignited a fire by friction, rubbing two pieces of wood together and setting light to the inner bark of the gum-tree, which burns like tow.71 Mr Shaw, the superintendent, gave us a basket and some clubs made by the natives, and as we drove away three hearty English cheers rang through the air, partly, I am afraid, for the lollipops and tobacco we left behind! (Stafford, 1889: 32–33).

As far as can be gleaned from Stafford’s account and newspaper reports, this visit to Coranderrk was the only encounter the party had with Aboriginal people in Australia.

The Aboriginal skill at fire-making, along with boomerang and spear throwing, and basket making, was a traditional skill that tourists to Coranderrk found particularly interesting. Ethel Shaw has discussed the practice in some detail:

Fire-making required both skill and strength to produce it quickly. At Coranderrk the natives used a soft white wood with a pith in the centre. This they called “doitborke,” meaning “fire.” They took a piece of wood about two feet long and 2½ inches in diameter. This was split into two pieces, showing the pith running down the centre. A few notches were cut on the flat side of the wood. These were rounded as a socket for the rubbing-stick, and also grooved slightly to allow the “fire” to drop out on to a small bundle of dry bark placed underneath the wood. The rubbing-stick, a thin, round twig of the same shrub, was placed upright in the socket and rubbed between the palms of the hands, beginning at the top to near the bottom of the stick, exerting pressure as the hands descended. The resultant hot dust would fall on to the bark, which was then taken up and gently waved in the air, fanning the hot dust and thus igniting the bark (Shaw, 1949: 33).

4.4 Lady Brassey, June 1887

Anna (Annie) Brassey, Baroness Brassey (nee Allnutt) (7/10/1839–14/9/1887) was an English traveller and writer (see Figure 4.3). She married Sir Thomas Brassey (later first Earl Brassey) (11/2/1836 – 23/2/1918) in October 1860 and they had five children before they travelled abroad on their luxury yacht Sunbeam . The family’s first circumnavigation of the world was in 1876–7 in the Sunbeam . Their last voyage was to India and Australia, undertaken from November 1886 to improve her health. She died en route to Mauritius on 14 September 1887 from malaria and was buried at sea. Upon the return of the Sunbeam to England in December 1887, Lord Brassey placed his late wife’s journal and manuscript note in the hand of M.A. Broome to edit them into an account of his wife’s final voyage. Lord Brassey also kept a private journal called the ‘Sunbeam Papers’ printed for private circulation,72 however, they are silent on Healesville owing to the fact that only Lady Brassey made the excursion to the upper Yarra.

Figure 4.3: Lady Brassey.73

The Sunbeam arrived at Melbourne on 12 June 1887. On 29 June 1887 Lady Brassey paid a visit to Healesville and Coranderrk whilst her husband sailed for Sydney for a brief visit.74 Later, Lady Brassey joined her husband in Sydney by taking the train as far as Albury where they transferred to Lord Carrington’s carriage that took them on to Sydney. Lady Brassey wrote the following account of her visits to Coranderrk – note that she misspells the station name as ‘Koordal’.

Wednesday, June 29th. … Further on we came to Koordal [sic], a ‘reserve’ for the aboriginals. It has a nice house, and the land is good. The aboriginals are rapidly dying out as a pure race, and most of the younger ones are half-breeds. Even in this inclement weather it was sad to notice how little protection these wretched beings had against its severity. We passed a miserable shanty by the side of the road, scarcely to be called a hut, consisting merely of a few slabs of bark propped against a pole. In this roadside hovel two natives and their women and piccaninnies were encamped, preferring this frail shelter to the comfortable quarters provided for them at Koordal [sic]. The condition of the men of the party contrasted very unfavourably with their appearance when they presented themselves under the charge of Captain Traill, the Governor’s A.D.C., at his

Excellency’s Jubilee levee last week. To-day they looked like the veriest tramps, and were most grateful for a bit of butterscotch for the baby and the shilling apiece which we gave them after an attempt at conversation.

From Healesville we rattled merrily over an excellent road, the scenery improving every mile, till we reached the picturesque little village of Fernshaw, a tiny township on the river Watt. … From Fernshaw up the Black Spur must be a perfectly ideal drive on a hot summer’s day, and even in midwinter it was enchanting. … Precisely at half-past two we started on our homeward journey, and with the exception of a few minutes’ stay at Healesville to water the horses, and at the blacks’ camp to have a little more chat with them, we did not stop anywhere on the way. Since morning the blacks had turned their huts right round, for the wind had shifted and they wanted shelter from its severity.

The Hastings Museum in Hastings, East Sussex, holds the Brassey Collection in the Dunbar Hall.75 This collection consists of some 6,000 items of art, ethnography, archaeology and natural history donated to the museum in 1919.76

4.5 Lord Brassey and family, October 1897

Lord Brassey served as Victoria’s final colonial governor from 1895 until 1900 (see Figure 4.4). During his appointment as Governor of Victoria he had an opportunity to visit Coranderrk in 1897, some ten years after his late wife Annie Brassey (see above) had visited the station during her last voyage on The Sunbeam . In the intervening decade Lord Brassey had remarried. We can only speculate as to the mixed emotions he may have experienced visiting the station with his new family knowing that his first wife had visited the station some ten years earlier without him. The governor and his family had visited Healesville in December 1895 on a private visit; but there is no indication that they called into Coranderrk (The Australasian, 14/12/1895). They returned on 23 October 1897 spending a weekend in Healesville. The Argus (26/10/1897) reported on their visit to Coranderrk. It refers to a discussion that Lord Brassey had with an ‘intelligent black’, William Barak, who told him how he had acquired his fire making skills:

The Governor on Tour. Visit to Coranderrk. An Aboriginal’s Present to the Queen. (By our special reporter). …

en route to St. Huberts a call was made at the Coranderrk aboriginal settlement, where the gallant little handful of surviving blacks welcomed His Excellency the Governor and Lady Brassey with exclamations of loyalty and exhibitions of boomerang-throwing. One intelligent black affirmed to Lord Brassey his belief in the existence of a Supreme Being, who had taught him how to produce fire by rubbing two pieces of stick together – a curious survival of the old

Figure 4.4: Lord Brassey, c. 1895-1900, State Library of Victoria Pictures Collection Accession No. H16.

Promothean legend, which students of comparative religion might find significant.77 He added a naïve expression of regret, however, that the Ruler of the Universe had not taught him how make blankets. About 80 men, women, and children of varying degrees of blackness were marshalled for inspection, and displayed their accomplishments to their own intense gratification. A striking feature in this coloured population is the large proportion of half-castes and quarter-castes, the inky colour-scheme of the pure-bred black paling by infinite gradations through the varying tints of cocoa and dry biscuit until it reaches at last the interesting pallor of well-made cheese.

The Healesville Guardian also published an account of the visit. This account adds that the Governor was presented with a basket with carved emu eggs.

VICE-REGAL VISIT.

The Government House party, consisting of his Excellency Lord Brassey, Mr. Albert Brassey, M.P., the Misses Brassey, Mrs. Neville, Lord Richard Nevill, Mrs. T.K. Smythe, Mr. E. Fitzgerald and Mr. E. Lucas, arrived on Saturday night. Attended service in the Church of England on Sunday, when his Excellency read the lessons. Lady Brassey arrived by the Sunday train, and in the afternoon the vice-regal party went up the Black Spur to the Hermitage. Mr. Lindt, however, not expecting this honor, was not at home. On Monday morning the party drove out to Coranderrk Aboriginal Station, where they were received by the superintendant, Mr. Joseph Shaw. About 70 blacks were present, and sang the National Anthem heartily. Lady Brassey was presented with pretty native made baskets made with wild flowers and ferns, and the other ladies of the party received smaller similar presents. A specially made basket and some nicely carved emu eggs were given to Mr. Albert Brassey, M.P., with a request that he would present them on behalf of the Victorian Aboriginals to her Majesty the Queen, a task which he kindly promised to perform. An exhibition of spear and boomerang throwing was given by the male portion of the tribe, and fire lighting by rubbing two pieces of wood together was accomplished by King Barak, greatly interesting the visitors, who left substantial monetary gifts behind them when they departed (Healesville Guardian, 29/10/1897).

Table Talk (29/10/1897) ran the following story:

Lord Brassey paid his first visit to the Victorian Aboriginal settlement at Coranderrk this week. There are still a few pure-blooded descendants of the once powerful Yarra tribe at the settlement, and … how they maintain their tribal traditions and beliefs despite two generations of supposed civilization. One of the aboriginals, known as Mrs Rowan persuaded Mr. Albert Brassey, M.P., to … of a finely woven grass basket which she had made for the Queen. Another, aboriginal, the …. “King William “—he is very wrathful … addressed by the summer excursionists to Healesville as King Billy—presented Lord Brassey with a picture of a corroboree, painted in black and yellow on a slab of wood about 3ft. long by 2ft. high. The Australian blacks have a traditional style of art but unfortunately “King William” has allowed himself to be influenced by advertisement … and illustrated newspapers.

The Gippsland Times also ran a story on the visit, however, the contributor was unable to appreciate Barak’s art:

(“Atticus” in the Leader.)

Undeterred by his Queensland experiences, his Excellency the Governor has paid visit to an mission station; at Coranderrk Lord Brassey and his party were received by a most decorous and sober lot of blacks, and the Governor was presented with an aboriginal painting by the royal artist, King Billy, of the Yarra Yarra blacks, who once ruled this part of the country from his palatial on the apex of Eastern Hill. The artist explained that this picture (his masterpiece), represented a corroboree, but it looks more like a pattern for a crazy quilt – that is, an unusually crazy quilt. However, in the course of a few years, when the artist is dead, and the painting has become an old master, it will, no doubt, have acquired considerable historic and artistic value. I remember seeing an aboriginal drawing that looked like a child’s reproduction of a section of Cleopatra’s needle knocked down for £6 at a Sydney art sale, where a somewhat ambitious work by a local European artist, who has quite a magnificent opinion of himself, only fetched £4 10s (Gippsland Times, 1/11/1897).

4.6 Officers from the Italian warship Puglia, September 1901

In September 1901, several officers from the Italian warship Puglia visited Coranderrk. The warship had arrived in Melbourne on 14 August 1901 from Adelaide (Bendigo Advertiser, 15/8/1901). On board were 12 officers and 272 men (The Mercury, 17/8/1901). The cruiser was under the charge of Capitano di Fregata Andrea Canale (The Argus, 14/8/1901). The warship left Spezia on 4 June, and called at Port Said, Aden, and Colombo leaving for Australia on 30 July.78 The local Healesville newspaper published a brief account of their visit to Coranderrk:

Yesterday several officers of the Italian warship or man-of-war Puglia, which is at present located at Melbourne, paid a visit to Healesville. In the morning they visited the Coranderrk aboriginal station, and during the afternoon the scenery around Fernshaw was viewed by the holiday-makers (Healesville Guardian and Yarra Glen Advertiser, 13/9/1901).

4.7 Dr Henry Lowther Clarke, Anglican Bishop of Melbourne, September 1904

In September 1904, Dr Henry Lowther Clarke, the Anglican Bishop of Melbourne paid his first visit to Coranderrk. Dr Clarke (1850–1926) was vicar of Huddersfield when he was appointed bishop of Melbourne in February 1903. The Argus (10/9/1904), revealed that the ‘Bishop of Melbourne has made arrangements to spend next Tuesday and Wednesday at the Coranderrk Aboriginal Station, and a visitation in the neighbourhood of Healesville’. The local Healesville paper presented a detailed account of the visit. As well as the usual performances of boomerang throwing and fire making and displays of their curiosities, the Coranderrk people performed a corroboree with singing:

The Right Reverend the Bishop of Melbourne, accompanied by Mrs Clarke and their two sons, paid a visit to Healesville on Tuesday and Wednesday last. They were during their stay the guests of Mr and Mrs Shaw, of Coranderrk station. Tuesday was spent in looking round the black station. The natives showed many of their aboriginal curiosities, boomerang throwing, fire making and corroboree singing, to the great interest; and delight of the visitors. In the evening a short service was held in the station chapel, at which nearly all the natives were present. The Bishop addressed some kindly and brotherly words to his congregation, which, as he said, was unique, as far as his experience had gone. Wednesday, in spite of the variable and chiefly inclement weather, was spent on a trip, over the Blacks’ Spur, the party, going as far as Mr Lindt’s. For tea they were the guests of Mr and Mrs Gilbert at Gracedale House. They left by the evening train, thoroughly pleased with their outing (Healesville Guardian and Yarra Glen Advertiser, 17/9/1904).

The Wanganui Chronicle (20/10/1904) reported that the visit had convinced the Bishop of the value of Aboriginal missions:

Dr. Clarke, Anglican Bishop of Melbourne, says a visit to one of the aboriginal settlements has convinced him of the wisdom of the work the church and State are doing for the remnant of the original inhabitants of Victoria, and that the vague talk of about the now intellectual and moral character of the race is false in the light of the results obtained by the kindly fostering care shown on the mission stations.

4.8 Sir Reginald Arthur James Talbot, Victorian Governor, October 1904

Sir Reginald Talbot served as Governor of Victoria from 25 July 1904 until 6 July 1908. He visited Coranderrk at the end of a long weekend stay in Healesville in October 1904. Unfortunately the article is to the point and reveals little of his visit to Coranderrk:

The State Governor, Sir Reginald Talbot, Lady Talbot and party visited Healesville on Saturday by the midday train, and stayed at Gracedale House. Mr Bancell, of the Metropolitan Board of Works, acted as guide, and piloted the distinguished visitors to the various places of interest. In the afternoon, the Watts Weir was visited, His Excellency demonstrating his prowess with the rod and line, and on Sunday, the party drove to the Hermitage. On Monday, the Coranderrk aboriginal station was the chief source of interest, and lunch was taken at the Terminus Hotel. The party returned to the city by special train on Monday afternoon (Healesville Guardian and Yarra Glen Advertiser, 8/10/1904).

4.9 Alfred Hugh Fisher, Visual Instruction Committee of the Colonial Office, June 1910

In Natalie Robarts’s diary for 3 June 1910, she has the following entry concerning a visit to Coranderrk of a ‘Mr and Mrs Fisher’:

We had today the visit of Mr. Keogh79 and a Mr. and Mrs. Fisher who belong to the ‘visual committee’ formed actually by our present queen. After her visit in the late King’s dominions she realised that the home people knew little or nothing regarding the Colonies – so a committee was formed to personally visit and gather information from all the Colonies. Mr. Fisher sketches and takes photos. He had King Anthony as his model asked several questions regarding this Station & the people he does that everywhere he visits & all that is put into book form for the use of the school (Robarts diary 3/6/1910 in Clark, 2014b: 47).

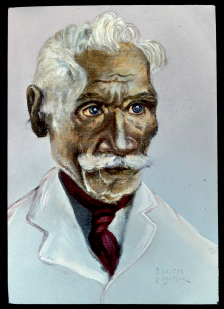

Figure 4.5: Alfred Hugh Fisher80

Alfred Hugh Fisher (1867–1945), was an English-born etcher, engraver, illustrator, and painter. He was appointed in July 1907 as an artist to the Visual Instruction Committee of the Colonial Office. His appointment came with a salary of £25 per month plus travelling and subsistence fees. His job was to illustrate lecture materials about the British Empire that the Visual Instruction Committee was producing for British school children. To prepare him for his photographic work he underwent training in photographic techniques. He was encouraged to spend several days in the places he visited so that he could absorb the atmosphere of each place more effectively. He was authorized to purchase photographs of important places he was unable to visit. He was to have the educational rather than the pictorial aspect in mind and he was instructed by the committee to present the ‘native characteristics’ of each colony and the ‘super-added characteristics due to British rule’. For the next three years he travelled extensively throughout the British Empire taking photographs and making sketches. His visit to Australia was part of his final tour for the Committee.

H.J. Mackinder (1911:84) has explained that the Visual Instruction Committee took the view ‘that children in any part of the Empire would never understand what the other parts were like unless by some adequate means of visual instruction’ and that where possible ‘the teaching should be on the same lines in all parts of the Empire’. The Committee eventually came to the view that the illustrations used for teaching should be prepared on a uniform system by an artist especially commissioned and instructed for the purpose. With financial support from the Queen and others, Alfred Hugh Fisher was appointed. The Visual Instruction Committee favoured the use of the lantern slide – as the ‘object in visual instruction is not to render thought unnecessary, but rather to call forth the effort of imagination’ (Mackinder, 1911: 85).

Fisher published an account of his travels through India and Burma (Fisher, 1911),81 but did not produce an account of his experiences in Australia. Fisher’s travel journals (in the form of letters to his colleague Halford Mackinder) are in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. They concern his visits to Australia, Borneo, Canada, China, Fiji, Hong Kong, New Zealand, etc. In his personal diary, Hugh Fisher made the following entry regarding his visit to Coranderrk. He indicates that he entered into a dozen huts – he considered the ‘whole visit was by far the most melancholy experience I had in Australia’.

The weather was wintry wet and disagreeable – June 2 for instance was wet all day with a few short intervals of chilly sunshine – we left Melbourne that evening from Flinders Street station for Healesville and thought what a contrast it all was with our run out to Warburton (in the same direction) at Christmas time. We reached Daly’s Hotel Healesville at 8.30 p.m. and the next day were taken by a Mr. Keogh, President of the “aborigines” board to see Coranderrk one of three native Reserves in Victoria, where 65 aborigines are confined in 2400 acres of land under the general care of a resident superintendent and a matron. At Lake Condah and Lake Tyers Mr Keogh said the same arrangements obtained.

The natives live in government built brick huts and are clothed in government supplied garments and fed upon government supplied food. I went into about a dozen of the huts and saw a number of the wretched creatures living at Coranderrk. The whole visit was by far the most melancholy experience I had in Australia. I made a painting during the afternoon of one called King Billy [sic] who wears a semicircular brass plate or crescent over his chest which, rightly or wrongly, he says was given to him by the Duke of York “my playmate Dook York”.82

Then there was more rain, and the Coranderrk natives went on dying and C. & I got up to “the Hermitage” – Mr. Lindts ideal rest place in the very heart of the forest up on what is called Blacks’ Spur.83

The Advertiser (3/12/1909) reported on the work of the artist:

SCENES OF THE EMPIRE. AN ARTISTS MISSION. Melbourne, December 30.

Mr. A. Hugh Fisher, artist, of the visual instruction committee of the Colonial Office is at present in Melbourne. He is a member of the Royal Society of Painters and Etchers, and his duty is to make sketches, paintings and photographs of the life, characteristic features, leading industries, manners, and customs in various parts of the Empire, so that school children may be enabled to form more accurate ideas of Greater Britain. This is the third year of this appointment. In the first year he visited Ceylon, India, Burmah, Aden, Somaliland, and Cyprus. Last year was mainly devoted to Canada, but in winter Mr. Fisher left Vancouver for China, and visited Wei Hai Wei, Hong Kong, also Singapore and British North Borneo, returning to Canada for the spring. He came here the other day by the Omrah, and his instructions are to visit New Zealand and Fiji before entering upon the work of depicting scenes in Australia. Mr. Fisher will go on to New Zealand in a day or two and will return to Australia in March. He expects to get very good material here. The Governor-General and the State Governors were advised by a dispatch from the Colonial Office of Mr. Fisher’s visit, and he bears letters of introduction to their Excellencies, and to some of the Commonwealth and State officials (The Advertiser, 31/12/1909).

After Mackinder left the Colonial Office project due to illness, the preparation of the lectures on Australia, British North America, the Far East, and Mediterranean colonies was taken over by A.J. Sargent, Professor of Commerce at the University of London. The Australian material was published by A.J. Sargent (1913). The book announced in its front pages that ‘A set of Lantern Slides has been prepared in connection with this book, and is sold on behalf of the Committee by Messrs. Newton & Co., 37, King Street, Covent Garden W.C. … from whom copies of this book can be obtained. The complete set of 489 slides may be had for £39’. In the preface it is confirmed that the lectures had been written by Arthur John Sargent and revised at the offices of the High Commissioners for the Commonwealth of Australia and New Zealand. The slides were derived from pictures painted and photographs taken by Mr. A. Hugh Fisher on behalf of the Committee, supplemented by photographs supplied from various sources. In terms of the eight lectures, lecture four concerned Victoria and Tasmania.

In the first lecture on Australasia, Sargent discussed the Aboriginal people of Australia:

Whether we look at the animals, plants, or aborigines of Australia, we are at once struck with the fact that they belong to an entirely different order of life from that which we find in the other great continents. The whole region seems, from a very early age, to have been cut off effectively from the rest of the world, and to have developed along lines peculiar to itself; though since the advent of the white man we have the artificial introduction of European and other plants and animals, which bid fair in many cases to oust the native products, just as the white man has displaced the original inhabitants.

The aborigines, as we found them, were as primitive as the plants and animals. They are not black, but a dark-brown people, and their hair is waved and silky, not curly like that of the negro. They are different also from the negro in the shape and build of the head and face. There are various theories as to their origin, but the nearest correspondence seems to be in some of the ancient hill tribes of India and the Veddas of Ceylon. At any rate they are quite different from the Malays, and equally also from the now extinct Tasmanians. The Tasmanians had woolly hair, and perhaps represented the remnants of an earlier and even less developed race than the invaders from the north.

The native Australian, as the first European discoverers found him, was not an attractive being. He was looked on as little better than a wild beast and treated as such. This was partly due to ignorance of his language and customs. His mode of life was fitted by long adaptation to the peculiar conditions of his surroundings. He had developed no agriculture in his new home; not without reason, if we think of the agricultural possibilities of the country in the hands of a rude and backward people. He was equally without any of the useful animals, and had no means of procuring them. So he was reduced to the nomad life and to the utilisation of the wild roots and plants of the country and such small game as he could kill with his rude weapons. …

The hostility of the native to the European colonists often arose from their interference with his natural food supply, or to their careless ignorance of his semi-religious ideas or customs, such as the tabu.

His only possible clothes were the skins of animals, and his weapons and tools all belonged to the Stone Age. The axe, knife, and hammer were in universal use, and long journeys were made to obtain the right kind of stone. This involved a certain amount of intercourse among the tribes. For weapons of offence the native had the club, and the spear tipped with bone or stone; while some tribes used a special spear-thrower. The boomerang was a curved bar of heavy wood, often five or six feet long, which was used for killing or stunning at a short distance. The smaller boomerang, which returns to the thrower, was merely a toy and used in sport; here we see it in use [Glass Lantern Slide 39 – Throwing the Boomerang]. The stone implements are all similar to those which are dug up in Europe, the relics of the Neolithic Age of man. One of the chief uses of the axe was to cut notches for climbing trees, in search of honey among other things; though they had another method which we see here [40 – Native Climbing a tree].

The natives were divided into tribes and sub-tribes, and had some form of tribal government, under head-men. In the south-east of the continent these chiefs had considerable authority and were sometimes treated by us as representing the tribe. Here is one of them, though he does not look imposing in his European dress [41 – Anthony Anderson] [see Figure 4.6]. They had an elaborate social system and curious marriage customs about which the learned still dispute. They had a strong belief in spirits of various kinds, though it could hardly be called a religion, and a whole series of tales and legends handed down orally, some of them showing considerable power of imagination. They even had the beginnings of some ideas of art and ornament [42 – Native Paintings], as we can judge from the crude paintings shown here [43 – Native Paintings].

The most interesting of their social customs was the corroboree [44 – Corroboree], a great gathering for feasting and dancing, often combined with some religious or social ceremony. Such meetings represented the only real social intercourse of the people and tribes, except messages by ambassadors who were sacred everywhere.

On the whole, then, they were not so low in the scale of civilisation as the early observers imagined. Even the language, with its many dialects, due to the absence of writing and the nomad life of the people, is elaborate and inflected like those of Europe.

Figure 4.6: Anthony Anderson, glass lantern slide, A. Hugh Fisher, S.J. Jones collection of views of Australia; Australasia A.M.M. Set 1, 41. State Library of Victoria Pictures Collection, Accession no. H82.43/135.

The native life in its original form is decaying, and survives chiefly in the interior and the west. Wherever white occupation has extended, the native is dying out; in fact, in some parts he survives only on the Government Reservations. Here are some of these survivors in Victoria [45 – Native Reserve, Victoria] [See Figure 4.7]. Here again, in Queensland, we see the native converted to European clothes, though he does not seem very comfortable in them [46 – Group of Natives, Queensland] [47 – A Native Woman, Queensland]. In this district, as in South and Western Australia, and the Northern Territory, they still exist in considerable number; but it is probable that there are less than 100,000 in all in the Commonwealth. In the census of 1911 an attempt was made to count them, and some 20,000 were found to be living in or near white settlements; only a vague estimate was possible in the case of the tribes of the interior, who still live their nomadic life in the more inaccessible parts of the country. But the area untouched by the white man grows smaller every year, and unless the native can change his character greatly, he is likely to die out in the north and west as in the south-east. In 1911 there were only about two thousand in New South Wales, hardly any in Victoria, and none at all in Tasmania. It was inevitable that the Australian native should be displaced from his hunting grounds (Sargent, 1913:14).

Butlin (1995: 182) has noted that the promotion of empire through books, illustrative materials, and educational syllabuses was widespread, part of an education policy geared to cultural imperialism, the imperial curriculum and the materials produced providing what Mangan has called ‘images for confident control’ and racial stereotypes used in imperial discourse. MacKenzie (1984: 162) considers the work of the Colonial Office Visual Committee to be one of formal, official imperial propaganda. The committee was tasked with providing the people of the United Kingdom and its Dominions and colonies with ‘a more vivid and accurate knowledge than they possess of the geography, social life, and the economic possibilities of the different parts of the empire’ by making available lectures with accompanying lantern slides for use in schools. However, MacKenzie (1984: 34) observes that the Visual Committee failed in its efforts at imperial propaganda because it embraced the technique of the lantern slide at a time when it had already become obsolete with the advent of film. The magic lantern had been invented in the seventeenth century and by the late nineteenth century had achieved a degree of standardisation. Lantern slides were found particularly suited to travel and missionary subjects – missionaries and explorers used halls and theatres to show slides.

Figure 4.7: ‘Native Reserve, Victoria’, Glass Lantern Slide 45, Photographer Arthur Herbert Evelyn Mattingley; Arthur Mattingley Collection, State Library of Victoria Pictures Collection, Accession no. H84.488/176.

4.10 Lord and Lady Denman, March 1912, April 1913

In March 1912, Coranderrk matron, Natalie Robarts made a very brief diary entry concerning a visit from Lord Denman, the Governor General of Australia, and Lady Denman: ‘Mme Melba, Lord and Lady Denman came to the Station by Motor, she [that is Melba] seemed not in a happy mood. Lord & Lady Denman very nice’ (Robarts diary 20/3/1912 in Clark, 2014b: 53).

The Healesville community were earnestly preparing for the planting at Fernshaw of ‘the Queen’s Acorns’. When she was the Duchess of York, Queen Mary had picnicked at Fernshaw and to commemorate the occasion the Healesville Tourist and Progress Association had applied to the Queen for some oaks, to be planted at the spot. The Queen had complied with the request. The first lot sent failed to germinate, so a second set was requested. ‘The acorns were handed over to the care of Mr Cronin, curator of the Botanical Gardens, and word was officially received from Lord Richard Neville last week by the Progress Association that they had germinated’. Lord Neville suggested to the tourist association that Her Excellency Lady Denman should be invited to be present at the official planting (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 29/11/1912). During their preparations there was ‘A suggestion that Mr Robarts be asked to co-operate in taking what steps he thought advisable in bringing the natives of Coranderrk to participate in the proceedings was readily accepted, and it was decided accordingly’. After much planning, the planting ceremony was set for 11 April 1913. Natalie Robarts made the following entry in her diary regarding the plantings:

Yesterday was a great gala day for Healesville. Lady Denman came to plant the Queens-oaks – she was received by the school children singing the national Anthem ... John Terrick & Ted Collett were arrayed in native garb of 1868 [sic] with weapons etc. etc. Lady Denman seemed much amused & interested ... she was presented with a boomerang with an inscription on a silver plate ‘Presented to Lady Denman by the natives of Coranderrk on the occasion of the planting of the Queen’s oaks’ (Robarts diary 12/4/1913 in Clark, 2014b: 55).84

After the Fernshaw planting, it was decided to plant two historical oaks in Queen’s Park where ‘A presentation will also be made of a boomerang, suitably engraved, from the natives of Coranderrk’ (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 4/4/1913). The local paper reported extensively on the celebrations. The arch of welcome had the words “Welcome to vice-Royalty” being on one side, and “Safe Return, Good Luck” on the other. In the centre was a painted coat-of-arms, and on the opposite corners a Kangaroo and Emu were depicted. The structure was decorated with flags and greenery and on opposite sides pedestals were constructed. One, upon which stood three aborigines, surrounded with the various native arms of war, was decorated with purely Australian foliage, and the words “Terra Australis, 1768” stood out boldly. On the other pedestal, Ivy Hall, and Masters Hall and Reg. Potter, three fair young Australians, presented quite a different appearance, and these represented Australia in 1913. According to the reporter, the effect of the tableaux lent a touch of originality to the scene, and Her Excellency was much impressed with the spectacle. At Queen’s Park Lady Denman and party partook of afternoon tea, after which the Hon. Thomas [her son] was presented with a boomerang by a picaninny, and the Hon. Judith [her daughter] with a native basket (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 11/4/1913). Another paper gave a little more information on the activities at Queen’s Park:

The Australian blacks from Coranderrk assembled in the park [Queen’s Park], and two of the little piccaninnies, on their behalf, presented the Hon. Thomas Denman with an ornamented boomerang with gold inscription plate, and the Hon. Judith Denman with a basket of native workmanship. The blacks gave demonstrations of boomerang throwing and fire lighting with sticks (Table Talk, 17/4/1913).

4.11 Sir Arthur Lyulph Stanley, Victorian Governor, April 1919

Sir Arthur Stanley served as Governor of Victoria from 23 February 1914 until 30 January 1920. Natalie Robarts diarised his visit to Coranderrk on 7 April 1919. The residents took the opportunity of the Governor’s visit to raise their concerns about the closure of Coranderrk and their removal to Lake Tyers Aboriginal station. Lanky Manton informed the Governor ‘he would be shot before he would leave’. Violet and Alec Mullett also made strong pleas to the Governor to be allowed to stay at Coranderrk. W.H. Everard, a member of the Board, and a local parliamentarian, assured them ‘there would be no compulsion’.

The state governor Sir Arthur Stanley with party visited the station today. It was a perfect autumn day. Mr Everard the member for Evelyn & also member of the Aborigine’s Board brought the party.85 Sir Arthur was very pleasant, he is a real type of an English gentleman, taking an interest in all things, cordial to one & all & ready to enter into any happy suggestion regarding the welfare of the Aborigines. One almost forgot the ‘Excellency”. We entertained the party at morning tea in the drawing room, which looked particularly attractive with beautiful autumn roses & leaves & the pale sunshine peeping through the windows. We all had a very enjoyable morning. ... Lanky, Violet Mullett & Alec addressed the governor pleading that they be not sent to Tyers. Lanky said he would be shot before he would leave. His Excellency was very diplomatic & referred their petition to Mr Everard who was hardly ready for this, His Excellency however warning him not to make rash promises (Robarts diary 7/4/1919 in Clark, 2014b: 78).86

The Governor’s visit to Coranderrk was reported in The Argus newspaper, highlighting the petition from the Aboriginal residents.

On the way to Healesville His Excellency visited the aboriginal station at Coranderrk, where the aborigines gave an exhibition of fire making and throwing boomerangs and spears. “Lanky” Manton, the one pure blooded aborigine on the station, produced fire by rubbing two sticks together, and gave His Excellency a light for his cigarette. The aborigines are much exercised about the proposal to remove them to the Lake Tyers station, and “Lanky” and others asked that they should be allowed to remain at Coranderrk. “They will never move me away unless they shoot me,” said “Lanky.” Mr Everard, who is a member of the Aborigines Protection Board, gave an assurance that there would be no compulsion. There is a proposal to take the 2,500 acres now used as an aborigines’ station for repatriation purposes, but the aborigines claim that they were promised years ago that they would be allowed the use of the land for all time. After being entertained at morning tea by the superintendent of the station (Mr. Robarts) and Mrs Robarts, the party went on to Healesville, where His Excellency was welcomed by the president of the Healesville shire (Councillor Burnside) (The Argus, 8/4/1919).

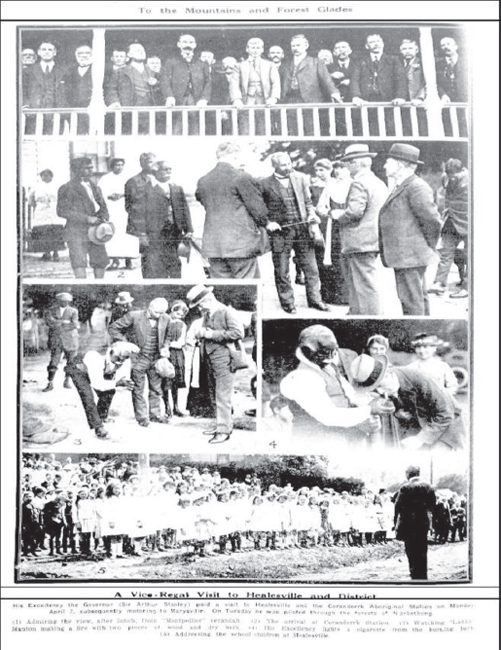

Table Talk published a montage of five photographs of the Governor’s visit to Healesville, including three taken at Coranderrk (see Figure 4.8).

4.12 Sailors From H.M.S. Renown, May 1920

In 1920 the Prince of Wales visited New Zealand and Australia as part of a tour of the British Dominions making his voyage in H.M.S. Renown. The Renown left Portsmouth, England, on 16 March, and visited New Zealand before embarking at Melbourne. In terms of the Prince’s itinerary it was expected that he would arrive in Melbourne on 26 May and remain in Victoria until 6 June when he would leave for Sydney (The Argus, 16/3/1920). The Healesville Shire Council made a number of unsuccessful efforts to be included in the Prince’s itinerary and then set about welcoming the sailors from the Renown (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 1/5/1920). Up to 500 sailors were expected to visit Healesville and the Superintendent of Coranderrk was asked if he could arrange a display by the Aborigines (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 15/5/1920). It transpired that 150 sailors visited Healesville:

“RENOWN” SAILORS. Visit to Healesville. On Friday, 4th inst., 150 sailors from H.M.S. Renown arrived by special train at 11 a.m. … Various kinds of sport were indulged in – displays in boomerang throwing and other purely Australian pastimes being the chief items (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 12/6/1920).

4.13 Lord Northcliffe, September 1921

Lord Northcliffe (Alfred Charles William Harmsworth), the famous media baron, visited Coranderrk in September 1921. Natalie Robarts made the following entry in her diary:

Madame Melba visited here today bringing Lord Northcliffe & a Mr York.87 Dame Melba was in a very good mood & pleasant to all. … the children sang & Mme was pleased with their singing.

Figure 4.8: To the Mountains and Forest Glades. A Vice-Regal Visit to Healesville and District (Table Talk, 17/4/1919). His Excellency the Governor (Sir Arthur Stanley) paid a visit to Healesville and the Coranderrk Aboriginal Station on Monday April 7, subsequently motoring to Marysville. On Tuesday he was piloted through the forests of Narbethong. (1) Admiring the view, after lunch, from “Montpellier” verandah. (2) The arrival at Coranderrk Station. (3) Watching “Lanky” Manton making a fire with two pieces of wood and dry bark. (4) His Excellency lights a cigarette from the burning bark. (5) Addressing the school children at Healesville (Table Talk, 17/4/1919).

She said they sang very naturally & did not keep their voices back, like most people do (Robarts diary 25/9/1921 in Clark, 2014b: 86).88

The local paper also published an account of his visit, and indicates that Northcliffe was greatly interested in the residents and wanted to hear a conversation in their native language:

Lord Northcliffe, accompanied by Dame Nellie Melba, paid a visit to Coranderrk Station on Sunday afternoon and was shown over the settlement by Mr C.A. Robarts. Lord Northcliffe was greatly interested in the residents, being particularly keen in listening to a conversation in the native language. A number of songs were given by the children, who were highly delighted at the appreciation shown by the visitors. After leaving the station Lord Northcliffe and Dame Melba motored over the Blacks’ Spur returning back to Melbourne the same evening (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 1/10/1921).

Lord Northcliffe died in August 1922 from infective or ulcerative endocarditis (Clarke, 1931: 300). His Australian travel memoir was published posthumously and edited by his brothers Cecil and St. John Harmsworth. In the Introduction they explain that it was Lord Northcliffe’s habit ‘to dictate his observations to one or other of the private secretaries who accompanied him on his travels, and to send sections home to be duplicated and circulated to the members of his immediate family circle. In the present volume the chapters correspond generally with the sections as they were received’.89

In a press release published in The Argus (7/9/1921) Northcliffe advised the Australian public that he was visiting Australia ‘for a holiday among Australian friends and family connections. I am not writing a book or anything else about Australia, except, perhaps, my opinion of the Commonwealth as a possible sphere for British investment and as a field for emigration. The other objects of my sojourn in Australia are rest and sunshine’. Tom Clarke (1931: 219f), the editor of the News Chronicle, who worked for Northcliffe, but did not accompany on him on his world tour, noted that Northcliffe had told him as far as his intended visit to Australia was concerned he wanted ‘to solve the Riddle of the Pacific and White Australia. I want to know and understand better this great Empire and the world at large. … I am growing older, and must see all I can quickly. I do not travel enough’ (Clarke, 1931: 221).

In the posthumously published account of his journey, Northcliffe briefly discussed his visit to Coranderrk. Note that he states that the residents make their living through farm work and by making boomerangs and baskets for sale to the public.

I did not stay long at the [Lindt’s] hermitage, for Melba likes moving about as much as I do. We went off to see a camp of aborigines – perhaps the only ones I shall see in Australia, because we may not be stopping at the northern parts of Queensland where they are numerous. They are short and ugly, with very wide faces. It is said there are fifty thousand left in Australia. They are most carefully protected by the Government, as are the Indians in Canada by the Canadian Government. Melba told me they had very good voices, and made them sing, which they did remarkably well. When it came to giving them some money, neither Melba nor I had any. I managed to extract a few shillings from the chauffeur. These aborigines live by farm work and making boomerangs and baskets for the public. One old man threw a boomerang. I have seen it done better at home (Northcliffe, 1923: 51–52).

When Lord Northcliffe visited Coranderrk in September 1921 he was in the company of Madame Nellie Melba. He was staying at Melba’s Coldstream home ‘Coombe Cottage’. Melba biographer Ann Blainey (2009: 308) describes Northcliffe as one of a galaxy of English guests who descended on the Coldstream cottage in 1921. Although his body was swollen with heart disease he proved to be an ‘easy guest’. Melba referred to his visit in her autobiography:

Nobody who knew the triumph of young Harmsworth could fail to feel deeply the tragedy of Lord Northcliffe. That last world-tour of his was the final gesture of a great man, but of a man already under sentence of death. When he arrived in Australia he came straight up to stay with me at Coombe, and I could hardly prevent myself crying out in pity, and alarm. The slim alert figure had grown heavy and swollen, the keen face was puffy and sagged, the bright darting eyes had lost their lustre. He gave me the impression of a man whose whole body was poisoned, as indeed it was. … Six months later he was dead (Melba, 1925: 275f).

Reflecting on Northcliffe’s publication of his world tour, the Sydney Morning Herald (14/7/1923) noted that the tour was ‘conducted at big speed and under high pressure’, and that Northcliffe was ‘a sick man in search of health’. Consequently, although he was a keen observer, it was not surprising that some of his observations were rather superficial and his generalizations rather hasty.

4.14 The British Squadron and Members of the Methodist Church, March 1924

In 1923–24, HMS Hood and the Special Service Squadron sailed around the world on ‘The Empire Cruise’ visiting ports of call of all the countries which had fought together in the First World War. The ships involved were battlecruisers under Vice Admiral Sir Frederick Field: HMS Hood and HMS Repulse and light cruisers under Rear Admiral Sir Hubert Brand: HMS Delhi, HMS Danae, HMS Dragon, HMS Dauntless, and HMS Adelaide . In March 1924, The Argus reported on their visit to Healesville:

Healesville, Thursday. Never before has Healesville presented such a gay and festive appearance as it did today, when 80 officers and men of the British Squadron, accompanied by clergy and members of the Methodist Church, visited Healesville. Other visitors accompanying the seamen numbered more than 100. … The visitors were then entertained at lunch by Mr. F.J. Cato, a leading member of the Methodist Church. Several toasts were honoured, after which exhibitions of boomerang and spear throwing, and fire-stick kindling, given by Coranderrk aborigines were witnessed. Pleasure trips over the Blacks’ Spur and other places of interest were made, and shortly before 5 o’clock the parties returned to Healesville, where tea was served in the Memorial Hall (The Argus, 21/3/ 1924).

The Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian (29/3/1924) added that after the official speeches in the Memorial Hall, the ‘gathering then dispersed and were entertained outside with exhibitions of fire-stick kindling, boomerang and spear throwing by “Lanky” Manton and “Billy” Russell.

Select References

Blainey, A. (2009). I am Melba. Melbourne: Black Inc.

Blainey, G. (Ed.) (1985). Oceana, or the tempestuous voyage of J.A. Froude 1885. North Ryde: Methuen Hayes.

Brassey, Lady (Anna Allnutt) (1889). The Last Voyage to India and Australia in the ‘Sunbeam’ (edited by M.A. Broome). London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Butlin, R.A. (1995). Historical Geographies of the British Empire, c. 1887–1925. in M. Bell, R. Butlin, & M. Heffernan (eds.) Geography and Imperialism, 1820–1940. Manchester: Manchester University Press (141–188).

Clarke, T. (1931). My Northcliffe Diary. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd.

Craig, J.W. (1908). Diary of a Naturalist being the record of three years’ work collecting specimens in the south of France and Australia (1873–1877) (edited by A.F. Craig).

Paisley: J. & R. Parlane. Fisher, A.H. (1911). Through India and Burmah with Brush and Pen. London: T.Werner Laurie.

Froude, J.A. (1886). Oceana; or England and Her Colonies. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

MacKenzie, J.M. (1984). Propaganda and Empire: the manipulation of British public opinion, 1880–1960. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Mackinder, H.J. (1911). The Teaching of Geography From an Imperial Point of View, and the Use Which Could and Should be Made of Visual Instruction. The Geographical Teacher. 6(2): 79–86.

Melba, N. (1925). Melodies and Memories. London: Thornton Butterworth.

Northcliffe, Lord (1923) My Journey Around the World 1921–22. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Nunn, W.H. (1963). James Anthony Froude A Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sargent, A.J. (1913). Australasia: eight lectures, prepared for the Visual Instruction Committee of the Colonial Office. London: George Philip & Son.

Shaw, E. (1949). Early days among the Aborigines: the story of Yelta and Coranderrk Missions. Fitzroy: The Author.

Stafford, Marchioness (Millicent Stafford). (1889). How I spent my Twentieth Year Being a Short Record of a Tour Round the World 1886–87. Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons.

Thompson, T.W. (1987). James Anthony Froude on Nation and Empire: A Study in Victorian Racialism. New York: Garland Publishing.

66 Presumably he also visited the memorial in Melbourne to his cousin, Robert O’Hara Burke ( Freeman’s Journal, 26/3/1892).

67 Hugh Halliday was in charge of Coranderrk in February 1877.

68 William Goodall was superintendent of Coranderrk at this time.

69 This was during Joseph Shaw’s superintendence of Coranderrk.

70 The Fourth Duke of Sutherland was known as the Marquis of Stafford between 1861 and 1892.

71 Tow is a short or broken fibre (such as flax or hemp) that is used for yarn, twine, or stuffing.

72 The ‘Sunbeam Papers’ were included in volume two of Voyages and Travels of Lord Brassey, K.C.B., D.C.L. From 1862 to 1894 (arranged and edited by Captain S. Eardley-Wilmot), 1895 Longmans, Green & Co., London.

73 Source: http://epsilon-del-camino-del-oro-blanco.over-blog.com/pages/Les_maitres_celebres_de_carlins-1841692.xhtml

74 Joseph Shaw was superintendent of Coranderrk at this time.

75 See http://www.hmag.org.uk/collections/durbar/collection/

76 I have not been able to confirm if the collection holds any items from Coranderrk.

77 This old black was probably the eminent elder William Barak.

78 Launched in 1898 and completed in 1901; the Puglia was used as a minelayer during WW1 and was retired from service in 1923. For more information see http://www.oz.net/~markhow/pre-dred/bits.htm#Puglia

79 Mr. Keogh is Hubert Patrick Keogh (1857–1938), M.L.A. for Gippsland North (1901–1908), and Vice-Chairman of the Board for the Protection of Aborigines. Keogh joined the Board in 1902.

80 Source: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/465981892664269565/

81 Fisher, A.H. (1911). Through India and Burmah with Brush and Pen . London: T. Werner Laurie.

82 Fisher has erred here; his subject was King Anthony Anderson.

83 Herbert F. West Collection of A. Hugh Fisher Series II Writings. Ephemera and Photographs. Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University Library, GEN MSS 795 Box 4 Folder 51 pp. 629–637.

84 According to the newspaper article, the period represented was 1768, not 1868.

85 W.H. Everard, MLA for Evelyn 1917–1950.

86 Maurice Robarts’s summary of his mother’s diary entry: ‘Visit by Governor Sir Arthur Stanley, & the local M.H.R. Mr Everard, Lanky Manton made fire with fire sticks for Governor, he & Alec Mullett made strong plea to vis itors to be allowed to stay at Coranderrk’.

87 Presumably, Bernard Yorke, the second son of Lord Hardwicke, who was staying with Melba at Coldstream.

88 Maurice’s summary of his mother’s entry: ‘Dame Nellie Melba visited today bringing with her Lord Northcliffe and a Mr York. Dame Nellie was in an excellent mood & praised the children who sang for her’.

89 During this voyage his travelling companions in Victoria included his brother-in-law, Harry Garland Milner, from Brisbane; H. Wickham Steed, then Editor of The Times, W.F. Bullock, New York correspondent of The Daily Mail, Keith Murdoch, Editor of The Herald, Melbourne; John Prioleau, principal private secretary; Harold W. Snoad, assistant private secretary; H. Pine, chauffeur; and Frederick Foulger, valet.