5 Journalists and Correspondents and Coranderrk

This chapter is concerned to analyse seventeen published accounts from journalists and correspondents who visited Coranderrk. They are of interest because they reveal the development of the station and show the evolution of Coranderrk as a tourist attraction and the response of the Aboriginal residents to this growing interest. Some accounts, such as that from a correspondent to The Argus (9/9/1876) indicate that Aboriginal residents, when it suited their purposes, were willing to use visitors as a way of making known their views about the way they were being treated whether they were issues with management or with the threat of station closure and forced relocation. In this sense residents’ willingness to take advantage of tourism is an extension of Lydon’s argument that they were using the occasion of visiting photographers to achieve their political ends. The correspondent to The Argus visited Coranderrk and gave an extensive report on conditions at the station. He concluded that ‘the blacks are possessed of very extraordinary notions in regard to their position on the station, and in regard to their rights and privileges. They are under the impression that the land they occupy belongs to themselves, and also the buildings, the stock, and all that is on the station. They regard the board and its white employees partly as usurpers and intruders, and partly as more or less inefficient and dishonest administrators of their (the blacks’) estate’.

5.1 An Easter Trip to Mount Juliet, April 1864

One of the earliest accounts of a tourist visit to the Coranderrk station was in the South Bourke Standard of 15 April 1864, a year after the commencement of the station. The author of the article gave an account of an Easter trip to Mount Juliet that included a visit to the Aboriginal station at Coranderrk. The party consisted of 20 people, five women, eight men, and seven Aboriginal people ‘who rode in front, acting the capacity of guides, and clearing the track of fallen branches and other obstructions’. What is interesting here is that some of the Coranderrk residents served as tourist guides to Mount Juliet.

5.2 With ‘The Last of the Mohicans’ on the Upper Yarra, July 1866

The Australasian (28/7/1866) published an account from a visitor to the Upper Yarra who spent an evening at Coranderrk. This writer drew comparisons between American Indians and Aboriginal people, and described the market for possum skin rugs and lyre bird tail feathers. Of course the reference to the Mohicans may be a deliberate play on words as Mohican was the name of one of the Aboriginal stations established in the district before Coranderrk commenced operations in 1863.

Half an hour’s dubious riding takes us among real savages of another class. We say dubious, for though the road to the blacks’ station for a bush track is not bad, the darkness by this time had settled in one dense mass upon the earth. So pitchy black indeed had the night become that the outlines of the trees were barely distinguishable, and the only clue to the position of the station was a faint reflection indicating some distant fire. In the Victorian bushland, any more than in the tropics, twilight hardly exists, and half an hour bridges the interval between the rosy sunset and the blackest night. The mare, however, pretty well knocked up with her yesterday’s work, plodded steadily onward. Then came the inevitable barking of dogs, and at once I rode into a camp of red American Indians, Siouxes, Hurons, anything you please-Cooper’s men, in short. At any rate it was a very close imitation of the Huron camp in The Last of the Mohicans . The mia-mias are much like the wigwams in Catlin’s exhibition, and as we paced fast by, through the smoke and flame of the fires within we glanced, upon dusky figures of the true savage type, some sitting, some lying, some stacking, some talking, and all at the sound of the horses tread starting to their doors to catch a glimpse of the passing strangers. A few yards more brought us in sight of a long, low building; and the sound of a hymn from many voices. It was the children’s tea time, and a very good tea it was!

This remarkable settlement owes chiefly its initiation to the philanthropic enterprise and indomitable perseverance of the Rev. Mr Green, its present superintendent. Some three or four years ago the aborigines were a perfect nuisance to the neighbourhood, alternating between starvation and drunkenness, either beggars or bullies. How quickly disease was carrying them off may be judged by the fact that the present number of 102 are the remains of nine tribes, the Yarra Yarra numbering at present only twenty, three, of the Goulburn, and five other whose names I forget. How completely intemperance, neglect, and disease have been the cause of this fearful diminution, maybe judged from the fact that since they have been collected together and properly managed numbers have not decreased, but increased from 98 to 102. Mr. Green and his excellent wife seem, besides unlimited zeal, to possess that rare quality which so seldom cronies with zeal, namely common sense. The blacks are neither over managed nor under managed, it would be too absurd to treat the adults, vagabonds from their childhood like good little children at a Sunday school. To put them into model cottages with glazed windows and slate roofs would be to smother them at once. They are therefore left to pig in their mia-mias in aboriginal fashion. For four days in the week they are expected to work, and, tell, it not in Gath, so well do they work that this year there will be sixty acres in cultivation, and the settlement will be nearly self-supporting. The other two they are allowed to go out into the bush and hunt. Formerly the game was abundant, but now, with so many expert hunters after it, it is necessary to go some miles off. Wallaby, of course, are good for food, and parrots and bandicoots by no means despisable; but the chief prizes are opossums for their skins, and the lyre bird for its tail feathers. The opossum rugs sell readily at £1 15s. untanned, and £2 5s. tanned. The exquisite feathers of the lyre bird, the Australian pheasant, sell as high as 5s. apiece, but the lyre bird is particularly difficult to shoot. It requires a practised eye to make out its whereabouts, and the blacks themselves are often at fault. The net produce of the hunt averages £120, out of which the men have to find their own clothing, such as it is. Formerly, of course, all would have gone in rum, but now drunkenness is extinct. Only two cases occurred in three years, and in both the delinquents were expelled by the Sanhedrim of their own countrymen, which sits once a month as a kind of aboriginal grand jury. Besides the produce, of the chase, each working adult receives from five to six pounds of flour, and the non-workers a pound less. A small quantity of sugar and tobacco is likewise given. The total expense to Government is thus only £4 per head. The children, thirty seven in number, reside in the house, and of course have to be entirely supported.

At eight p.m. a bell rang, and the whole settlement came trooping in to prayers. It was curious, glancing round on the crowded room, to see these swarthy faces turned towards the reader, most in vacant observation, but some evidently attentive. Positively, I do not think the native face repulsive. It is grotesque, and strikes one at first like a comic mask, but it has good points about it; the eyes are often good, though furtive and wild. Prayers over, all trooped out, each in passing shaking Mr. and Mrs. Green by the hand, and the settlement went peaceably to bed.

I could not help thinking, as I lay that night listening to the plungent dash of the rain, which augured ill for the expedition of the morrow, about all the doings of the day, and how much, after all, civilization was forth. Which were the more, civilized, Mrs. A and Mrs. B in crinolines tearing each other in the mud, or the grateful savages who are constantly bringing Mrs. Green rough presents because she has been kind to them? However,” Kismet ” as the Turks say. They are doomed. Be it so, but at any rate let their doom come to them as lightly as possible. Our treatment of the natives is anything but a white spot in the history of Australia, and if national death must come to its first inhabitants, let it be euthanasia (The Australasian, 28/7/1866).

5.3 Notes of a Trip to the Black Spur, March 1868

This newspaper article mentions the manufacture of baskets, rugs, and native implements to be sold as objects of curiosity to visitors. The author also challenged the commonly held view that the extinction of Aboriginal people was inevitable.

Notes of a Trip to the Black Spur

What interested me most of all in the course of my holiday excursion was the Black Station at Coranderrk, about two miles from Healesville. I was there two days; and the greater part of the third; enjoying the hospitality of Mr Green, the superintendent, and making myself familiar with the ways of the black fellows under his charge. I have often heard it said (and who has not?) that it is of no use attempting to civilise the blacks; that they are utterly incapable of civilisation; that they are a doomed race, fast dying out; and that the best thing to do with them is to let them alone, I never believed in this doctrine, and cannot believe in it after being at Coranderrk. I saw seventy-five blacks there, including men, women, and children; I saw them in their huts; I saw the men at work in the harvest field, reaping, binding and stacking the corn; I saw the women making baskets and tending their babies at home; I saw the boys in the school, and at play on the cricket ground; I saw them all attending religious service both week day and Sunday; I conversed with young and old repeatedly; and had it not been for the dark hue of their skin and the peculiar physiognomy of some of them, I confess I could hardly have noticed any difference between them and ordinary English farm laborers. They dress as our laborers do; and on Sundays they come to chapel clean and tidy, each in his Sunday suit, and with his boots well blackened. Some of the young women wear lace collars and brooches, and one or two of them are not without personal attractions. Their clothes are not provided for them be it understood. Each adult must keep himself in clothes, and a good rule – it is, if they are to be trained to habits of independence. Their industry is shown by the fact that they have between 60 and 70 acres under cultivation; that they grow wheat, oats, maize and potatoes, for the supply of the settlement; and that they do all the ploughing themselves, all the sowing and reaping, and in short all the work of a farm; requiring no more superintendence than any farmer is in the habit of giving to his men. They are allowed two days in the week for hunting and fishing; and by making opossum rugs, baskets and native implements, to be sold us objects of curiosity to visitors, they earn a little money, which amounts in the aggregate to about £100 per annum. Every man has his horses and cows bought with his own money. Last year ten of the men went to the Goulburn to assist in getting in the harvest, and earned £128. One of them, it is true, spent his moiety in drink on the way back, but he was a new chum; the others saved their earnings for judicious expenditure. There is not a man on the place now but has given up drinking habits long enough to show that he is capable of resolution, prudence and foresight, and some have given up smoking. The minority have been settled four years, without showing the least sign of hankering after their old roaming habits. They can all speak English, and read a little. Some of the girls are able to write letters to their friends. The boys are all merry enough, but the men are grave, even to sadness, in their looks; though they are losing in some degree that wildness of eye peculiar to the savage state. They are reserved and shy, especially with strangers. Their religious ideas and feelings I will leave to be inferred from what I have said regarding the progress they have already made in the common habits of civilisation (Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers, 3/3/1868).

The author was also somewhat critical of the research methods of the Rev. Julian Woods who had paid a fleeting visit to Coranderrk:

I am aware that the Rev. Julian Woods has pronounced them to be utterly ignorant in regard to religion; but let it be considered that he was at the station not longer than twenty minutes altogether, and that if he had an opportunity of conversing with any of the blacks at all, it was scarcely long enough for him to have penetrated that barrier of reserve which, as it characterises them generally in their intercourse with strangers, so does it most of all when religion is in question. Mr Woods is a man of science as well as a priest, and in dealing with human phenomena, as he had to deal at Coranderrk, I should have expected him to proceed inductively rather than dogmatically. He best knows why he allowed himself to lapse into the mere priest, and arrive at a conclusion without sufficient data to warrant it, or rather without duty at all (Illustrated Australian News for Home Readers, 3/3/1868).

5.4 A Week on the Yarra Track by “Beppo”, January 1874

A correspondent who used the nom de plume ‘Beppo’ noted that he and a friend called ‘Giacomo’ spent a week in the summer holidays in the vicinity of Mt Juliet and Fernshaw. One of the day trips they made was to Coranderrk:

On Sunday we paid a visit to the Blacks’ Station at Coranderrk on Badger’s Creek. We walked all round, conversed with the blacks, went through the hop plantation, and finally attended the service. The behaviour of the congregation was excellent, as was also the singing (The Telegraph, St Kilda, Prahran and South Yarra Guardian, 17/1/1874).

5.5 ‘Our Sable Brethren Live in Semi-civilized Comfort’, November 1874

Another correspondent identified as J.W.M. wrote an account of a week in the Yarra valley in November 1874. He explained that the motivation for his ‘week’s holiday in the country’ was a ‘desire to look upon the face of nature’. He chose to visit the ‘Yarra Flats’ where they stayed with a friend. After breakfast they arrived in Healesville and visited Coranderrk:

… This is one of several similar institutions provided for the purpose of sheltering the remnant of the aboriginal inhabitants of Victoria, and preserving them as far as possible from the destructive influences which seem destined to extinguish their race. Owing mainly, I believe, to the judicious management of Mr. John Green, the late superintendent (since promoted to some higher sphere of duty in the same service), a great deal of success has attended the work at Corranderk [sic], and numerous families of our sable brethren live in semi-civilized comfort on the station, whilst numberless paddocks are fenced in and cultivated. A large quantity of farm improvements and station stock, a hop garden, with drying kiln, &c., complete, and oven a system of waterworks bringing the water of the Badger Creek into the very centre of the tiny township, show that vigorous efforts have been made to turn their labor to some profitable account. … J.W.M. (Mercury, 30/1/1875).

5.6 Coranderrk – ‘Well Worth a Visit, But Go On a Week Day’, January 1875

‘Pedestriano’ promoted Coranderrk as well worth a visit, but cautioned that the visitor should go on a week day, as the station is preoccupied on the Sabbath:

On the morning of the 3rd January, the weather showing no signs of clearing up, in company with the representative of the Lands Office, I made tracks for Healesville, formerly called New Chum, where we were joined by the bonded store keeper and brother—and guided by the hotel keeper, Mr. Morrison, at once started for the Black Protectorate Station at Coranderrk, distant about three miles over a very bad road, very soft and badly in want of broken metal. The Black Station consists of a number of wooden houses, comfortably built, but few inside adornments, said not being appreciated by the natives, who appear to furnish their domiciles with “cooking utensils only.” There are about 100 blacks, a large number being children, the majority of the males, are handsome fellows, with large black timid-looking eyes, long black flowing hair, and whiskers and moustaches, for which many a young swell would give three years of his existence. The women are ugly, coarse, and uncouth creatures, and evidently do not relish being told that their husbands have a much darker complexion than the children. (Strange, but true, many of the children being almost white.) It being the Sabbath-day we did not like to intrude upon the Superintendent, and were thus unable to acquire information concerning the natives, such as their habits, diet, general health, future prospects, etc. We found an extensive hop garden in a most flourishing condition, and from which a handsome profit will be realised this year. … The Government have reserved a large area of land, to be in a position to extend the enterprise when feasible; much has been done, but a vast deal more, is yet to be accomplished. A new kiln for drying the hops was in course of erection, but we were unable to learn much concerning it, as the contractor received us with a curse; was not at all choice in his language, and evidently, not the class of man to impart information of an interesting or valuable character. Coranderrk is well worthy of a visit, but go on a week day. And should you be a man of Kent, you can readily imagine yourself transported to the hop gardens of Thong. … ‘Pedestriano’ ( The Record and Emerald Hill and Sandridge Advertiser, 18/3/1875).

5.7 Cricket at Coranderrk, April 1876

An account in The Argus of 6/4/1876 informed its readers of the intersection of tourism and cricket at Coranderrk. A cricket match between the visitors and a team from Coranderrk was an opportunity for the visitors to see how the ‘natives are housed, treated, &c.’

… A cricket match will be played between eleven of the natives and the visitors. The former have been hard at work practising for the event, and they are looking forward to it with great joy. The visiting eleven will comprise one or two fair players, but the remainder will be purely of the “muff” order, and gentlemen of some standing in the city. The tourists will start from Melbourne on Friday afternoon (The Argus, 6/4/1876).

5.8 ‘Under the Impression that Coranderrk Belongs to Them’, September 1876

In September 1876 a ‘special correspondent’ to The Argus (9/9/1876) spent a day at Coranderrk and published a lengthy report of their impressions. He concluded that ‘the blacks are possessed of very extraordinary notions in regard to their position on the station, and in regard to their rights and privileges. They are under the impression that the land they occupy belongs to themselves, and also the buildings, the stock, and all that is on the station. They regard the board and its white employees partly as usurpers and intruders, and partly as more or less inefficient and dishonest administrators of their (the blacks’) estate’. The identity of the correspondent is not revealed. The correspondent considered the ‘blacks at Coranderrk are a helpless, thriftless class’. Noting the station consisted of 4,850 acres, the correspondent could not believe that the station was subsidised by the state. ‘A thousand white people could support themselves on the Coranderrk Station, and require no subsidy; a still larger population of Chinese would get rich upon it’. The Aboriginal people at Coranderrk were the cause of this state of affairs: ‘He is there a pampered child, who expects to have everything done for him, while he does little or nothing in return, and he will only submit to discipline in so far as that may meet his own convenience and suit his taste’. The correspondent then described the day he spent on the station.

At 11.30 a.m. he witnessed a small émeute or small rebellion on the station. The hop workers had taken a break from work to have a smoke and had been advised by the hop manager that unless they resumed work they would not receive credit for their half-day’s labour. They went in search of the superintendent – Hugh Halliday. A ninety minute public meeting ensued in which they condemned the management of the station. They also asserted that their meat ration was insufficient; they could not live and work upon it.

The correspondent noted that Halliday had only been in office since March and ‘though he is doing his best to introduce some needed reforms, and has already accomplished a good deal, much yet needs to be done. The work is naturally slow. Official delay hinders it, and want of money, and most of all, the nature of the blacks themselves. They have never been taught to submit to strict discipline, and can indeed do pretty well as they please’. He considered Halliday ‘acts wisely in exercising a little patience, and endeavouring to introduce better habits by degrees’. The correspondent then noted that ‘The fact which impresses itself most forcibly upon the mind of a reflective visitor to Coranderrk, is, in the first place, that there should be no such establishment at all; and in the second that granting the establishment as an exorable circumstance, three-fourths of its inhabitants have no business to be there. ... They are as fit to earn their own living as the average white man, and they would probably be happier and more contented fighting their own way in the world than they are now’ (The Argus, 9/9/1876).

5.9 John Stanley James, aka ‘The Vagabond’, and Coranderrk

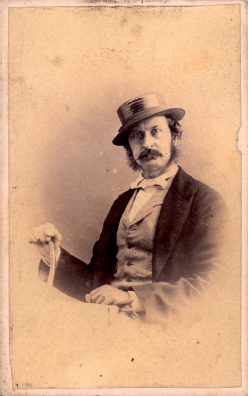

One of the greatest critics of Coranderrk in the nineteenth century was ‘The Vagabond’, aka John Stanley James aka ‘Julian Thomas’, who was a regular visitor to Coranderrk (see Figure 5.1). James visited Coranderrk at least four times – in 1877, 1885, 1888, and in 1893. In 1885–6 he also visited Framlingham, Ramahyuck, and Lake Tyers Aboriginal stations. After his first visit to Coranderrk in March 1877 he wrote ‘A Peep at “The Blacks”’ for The Argus .

In the published historiography of Coranderrk the work of The Vagabond has received very little prominence. Barwick (1998: 304) in her study of Coranderrk, presumably, borrows the title of his 1877 paper when writing about Coranderrk in the 1880s; she observes that the Blackfellows’ township had become ‘a shabby zoo where thousands of idle tourists visited on Sunday afternoons. They came for a ‘peep at the blacks’; they went away with their prejudices confirmed’. Jane Lydon (2014: n.p.) in a discussion of hop picking and its place in creating an Aboriginal idyll at Christian farming villages such as Lake Tyers and Coranderrk, refers to James’ inspection of the Coranderrk hop garden and his comment that ‘at a slight distance [they are] one of the prettiest sights in the world’.

John Stanley James (1843–1896) was an English-born freelance journalist who went to America in 1872 where he changed his name to Julian Thomas. He arrived in Australia in 1875 ‘sick in body and mind, and broken in fortune’. In 1876 he began to publish articles using the pseudonym ‘A Vagabond’ – and later changed this to ‘The Vagabond’ as he gained greater notoriety. He published a series on ‘the social life and public institutions of Melbourne from a point of view unattainable to the majority’, often based on first-hand reports of what it was like to be ‘inside’ certain institutions, a kind of investigative journalism or immersive journalism in which he went undercover. He brought to his observations a breadth of perspective gained from his knowledge of other societies. In a recent analysis by Willa McDonald (2014) James’s work is considered an early example of Australian literary journalism. According to Sims (2008) literary journalism is characterised by such things as immersion reporting, a focus on ordinary people, character development, complicated structures, symbolism, voice, and accuracy. Whitt (2008) considers literary journalism is interpretation, a personal point of view, whose focus is not institutions per se but the lives of those affected by those institutions. Jean Chalaby in his study of the history of journalism has described this field as ‘miserabilism’ (McDonald, 2014: 70), reporting on the evils of poverty and deprivation to an upper-class audience. The Wanganui Chronicle (29/11/1877), in referring to his fourth volume of the “Vagabond Papers” which included ‘A peep at the Blacks’ – his first article on Coranderrk, noted that he was ‘still finding plenty of social sores to probe’.

Figure 5.1: John Stanley James aka The Vagabond, J. Brown photographer, 1860. State Library of Victoria Pictures Collection, Accession No. H29809

James (1877 vol.1: preface, n.p.) described his work as ‘a new line of Australian journalism … I have everywhere been on “the inside track,” and write from that eligible vantage point’. He went into institutions such as the Immigrants’ Home, the Benevolent Asylum where he had himself admitted, working as a porter at the Alfred Hospital, attendant at lunatic asylums, and dispenser-cum-dentist at Pentridge gaol. James was interested in powerlessness and in his narratives he often positioned himself as an advocate for the marginalized and oppressed. Yet whilst he stood with the underclass in Melbourne society his advocacy did not extend to Aboriginal people. Although the Coranderrk Aboriginal station was only a short distance from Melbourne, it was one institution he did not investigate by going undercover –rather he accepted an invitation from his host to visit the station in March 1877 whilst he was staying in the Yering district. Evidently, James was not interested in the ‘inside track’ of Coranderrk – his interest was limited to a mere ‘peep’.

In 1884, James signed a three-year contract with the Argus newspaper to travel throughout regional Victoria describing country towns for a series entitled ‘Picturesque Victoria’. In the 1890s he published a second series of articles entitled ‘Country Sketches’ that concern his travels and adventures in south-eastern Australia. Cannon (1981: viii) considered the two series were ‘exhilarating’. Today, this writing would be considered destination journalism or travel writing.

5.9.1 ‘A Peep at the Blacks’: The Vagabond’s First Visit to Coranderrk, March 1877

James’s first article on Coranderrk was published in the Argus of 7 July 1877. It was republished in the fourth volume of the ‘Vagabond Papers’ in 1877.90 In the article James reveals that he accepts the familiar tropes, established narratives and racist myths about Aboriginal people that were prevalent in the latter part of the nineteenth century: their laziness; their inability to farm; and their addiction to alcohol. Julia Peck’s (2010) analysis of James’s writings is the opinions he expressed were indicative of the debates in Victoria at that time that led to the implementation of the 1886 Aborigines Protection Act (also known as the ‘Half-Caste Act’) which redefined Aboriginality on the basis of racial terms and reclassified people of mixed descent as ‘white’. In practical terms this meant that part-Aboriginal people between the ages of 14 and 34 were given three years before they were forced to leave Victoria’s mission stations and integrate and assimilate into European society and become self-sufficient. The immediate effect of implementation was a reduction in government spending and the attempt to fracture families. Barwick (1998: 197f) refers to it as a vicious article which represented the views of local residents ‘who coveted the reserve but he gave the impression that the criticisms were the views of staff’.

The Vagabond made his first visit to Coranderrk in March 1877 – former police sergeant Hugh Halliday was superintendent at this time:

A PEEP AT “THE BLACKS.” By A VAGABOND.

During my pleasant sojourn in the Yering Valley in March last, our host one day inquired, “Would you like to go and see the Blacks, ‘’ I assented dubiously, not at first being quite sure as to the description of amusement thereby designated. But I was very pleased when I found that “the Blacks” was the colloquial term in the district for the aboriginal station at Coranderrk. Two of our party refused to go, preferring cigars and grapes, and dolce far niente under the verandah.91 However two dear little friends and an eminent banker accompanied me. ....

We started after an early lunch, and driving through the lovely vineyard and across large paddocks, struck a slip panel, and emerged into the high road to Healesville. One mile of Australian bush road, except on the mountains, is much the same as another. En route we passed an old blackfellow, who, gun in hand, and with half a dozen dogs at his heels, was following his natural instincts as a hunter. Crossing the Yarra, we drove along fertile flats, and then turned sharply to the right along a bush track leading to the station. We passed trees with rude carvings on them, the figure writings, earliest efforts of all savage tribes. But whether this was a remnant of ancient aboriginal art, or an imitation of the white man’s, I cannot say. We soon arrived at the station, which is quite a settlement, comprising some 30 cottages or huts, schoolhouse, and houses of the superintendent and schoolmaster, kiln for drying hops, barns, stables, and other outbuildings. Driving along the street between the huts the first thing that strikes a visitor is the ample supply of water. There is a large open gutter on each side of the street, there is a water-tap in the centre, which is fed by pipes filled from Badger’s Creek, which runs through the grounds, having a large fall from its mountain source. There are few men to be seen about. Lubras were at the doors or outside of their huts, some lazily washing, others administering to their babies. The superintendent of the station was not at home, but the school-master, an intelligent and superior kind of man, did the honours of Coranderrk. The first thing we inspected was the hop garden. I have seen hop-picking in Kent – at a slight distance one of the prettiest sights in the world. Here, however, hops grow luxuriantly, and the long poles were covered with trailing plants, bent beneath a weight of blossoms. Hop-picking is a light, easy employment, and one would have expected to find all the hands on the station at work here. Not so, however; the gorgeous “bucks,” secure in the possession of free quarters, clothing, rations, and wives, will not work for the extra inducement of a shilling a day, but roam round the country, hunting a little, stealing a little, getting drunk occasionally, and generally having a remarkably good time of it. The Government-maintained heir of the soil scorns work, and hop-picking is apparently done by some of the lubras, a few old men and boys, and Chinamen from Melbourne. In real truth, however, the work is done by the latter, who being paid by the “pocket,” toil on with the patient, untiring industry of their race, being thus able to earn from 20s. to 25s. a week. The work done by the lubras, children, and old men is very little. They lazily pull at the poles, or lie in the shade. The women have all sorts of complexions, and their children are all sorts of colours. Dark women have light picanninnies and vice versa . Miscegenation appears to be practised to its full extent at Coranderrk. One very old blackfellow was pointed out to me whose boast it is that for years he never saw a white man without shooting at him; and he is believed to have killed a few in his time.

The Coranderrk reserve is about 5,000 acres in extent, and the hop garden only occupies 20 acres. The rest of the ground under cultivation comprises hay paddocks, potato field, fruit and vegetable garden, and orchard. The hop-garden alone affords any part of profit or return. There is little doubt that much more land might be brought under cultivation if the blacks would work, but when Chinese labour has to be employed to gather the hops now raised, it is evident that scant progress will ever be made in this direction. The greater part of the reserve is in primal scrub and bush, and is used as a cattle run, there being a good deal of stock on the station. Cattle are required to furnish the pound of meat daily with which each adult is supplied, and each family has also a cow. The few blackfellows who work act as stockmen and herdsmen; they like the excitement and pretence of labour which riding about affords them. After leaving the hop-gardens we went to look at the kiln where the interesting process of drying and packing the hops into bales is carried on. This was done by white men. A blackfellow cantered by us on a good horse. He was as well clad at the Government expense as any English labourer, and in every material respect has, to my mind, a better lot of it. The “cottages” at Coranderrk next claimed our attention. They are miserable and squalid enough, no doubt, made of paling and bark, but after all they are good enough for the occupant!, who do not desire, and will not trouble themselves to get, anything better. They are as good as negro huts in many parts of the States, and better and more healthy than many of the shanties in the purlieus of Little Bourke-street. Dr. M’Crea, I know, issued a strong report against the state of the huts at Coranderrk, but I think he will find in Melbourne city far more glaring examples for him to moralise on. Mind, I don’t say Coranderrk is a nice place, but it is good enough for its lazy, indolent inhabitants. The neglect and shiftlessness apparent all around reminded me very much of a free negro settlement. Offal and rubbish lying about; gardens, so called, overrun with weeds; turkeys, fowls, and ducks, apparently sharing the huts with their human inhabitants – all this is characteristic of the freed negro, who will, as a rule, do as little work as he can possibly help.

School hours were over, but the children scattered about the street and hop garden were hastily summoned to the schoolhouse for our inspection. There are about 25 boys and girls in the school, of all ages from 10 downwards, and all shades of colour from pure black to pure white. They sang one of Moody and Sankey’s hymns for our entertainment. “It is a small world,” said my friend. “The last time I heard that was in Exeter-hall, London. I little thought then I should be in company with ‘The Vagabond’ at a black station and listen to the same air.” As the children sang I inspected them, and my soul grew wroth within me. Why should these children with less than a quarter of black blood in their veins be condemned to be branded as “blacks,” so for ever associated with them, and be reared only to be the victim, wife or mistress as you will, of some lazy brutal blackfellow, her progeny being thus of a lower grade than their mother? Why could not they be raised at a state school, and given a chance in life away from the stupid and immoral influences of an aboriginal station? I know that this seems opposed to theories in which I was raised, but it is not so. In America, “coloured people,” those with a drop of white blood in their veins, will never mate with “black niggers,” and a Quadroon or Octoroon girl may be sure of finding that their children will possess more of white blood than they do. And so in time, our “peculiar institution” being abolished, the black blood is worked out, and five generations from the negro may be reckoned as pure white. Altogether, my opinion of Coranderrk is that it is but a Government breeding establishment, where the native and mixed races propagate in idleness. There can hardly be said to be a pretence of work on the part of the blacks there. They occupy valuable land near townships. Their women get seduced (if such a term can be used of those to whom chastity is an unknown virtue) by white people, and they all obtain drink from the same source. I know this has been denied, but inquiries in the neighbourhood satisfied me of its truth, and but the other day 16 blacks were brought before the magistrates at Healesville for being under the influence of liquor. If we must have a Government station for aborigines, I would say send them up the country, where they would be by themselves, free from the temptations of the white man. A far better plan, however, would, I think, is to send them to those parts of Australia where game still abounds, and where the squatters would pay them for every kangaroo killed. They would then follow out their own life, and be happy according to their lights, dying out by degrees, remaining savages perchance to the last. Civilise them, I hold, you cannot.

But humanitarians will say the land belonged first to the black man, who does not want Anglo-Saxon civilisation, but merely leave to occupy his heritage, and live his miserable, savage, brutal life in peace, “The land belonged to them, and there was a first wrong committed in taking what was not ours.” I say there was not. The earth belongs to those who will occupy and cultivate it, converting barren wastes into teeming pastures and fields of grain. Savages who live by the spoils of the chase can only thinly populate a country which, tenanted by civilised men will feed thousands. The apparent first wrong is after all a right, not on the ground of “the good old rule, the simple plan,” but following out a far higher law, “the greatest happiness of the greatest number.” The nomad savage who will not work, and who uselessly cumbers the ground, must disappear before the white man. It is so in America, where, however badly individuals may have behaved to the Indians, the nation has endeavoured to fulfil all its just obligations to the original occupiers of the soil. But in spite of all efforts the wild Indians of the plains can never be reclaimed. I have seen them at “agencies” and in reservations, I have seen them arranged in hostile line attacking a surveying party. I have ate with them, and fought with them, and am forced to the conclusion that General Phil Sheridan was right when he said, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” The American aboriginal is of a far higher type than the Australian, which will, happily for all, soon disappear from this continent. And when one thinks what they were and are, and sees how at Coranderrk, with its feeble attempts at civilising, and weak efforts to convert to Christianity (?), the savage character is so little changed, one is forced to the conclusion that it is useless to attempt to artificially preserve the remains of a race never lovely in itself, and whose members have only learnt – and will only learn – the vices of the white man, and none of his virtues (The Argus, 7/7/1877).

5.9.2 A Second Visit from ‘The Vagabond’, May 1885

The Vagabond returned to Healesville in May 1885,92 and noted in his subsequent article that the village was becoming a popular tourist resort. He described how at the Coranderrk Aboriginal station, globe trotters from Manchester and Birmingham were able to get their ‘first impressions of the Australian black fellow’ and ‘purchase badly made boomerangs and other curios’ as mementoes of their experiences. James described the Aboriginal people on the station as frauds with no picturesque points principally renowned for their laziness. He then gave a brief description of what can be seen at Coranderrk and concluded that those Manchester and Birmingham tourists with a commercial vein may be interested to know that the station had made a loss of over £5,000 in the previous year.

PICTURESQUE VICTORIA. By “THE VAGABOND”

Healesville is yearly becoming more popular as an inland holiday resort. … Metropolitan cockneys always find a deep joy in walking or riding to Coranderrk and Manchester and Birmingham globe trotters there get first impressions of the Australian black fellow, and purchase badly made boomerangs and other curios to take home to their family circles, mementoes of their experiences with the “Savage” of Australia in his native lair. The aboriginal on Government stations is, however, as most people know, a fraud. He has no picturesque points, and is principally renowned for his laziness. But at Coranderrk, visitors may be interested in the score of huts and cottages, the hop gardens and kiln, the school, also acting as a church, and the laundry and sewing rooms he will learn that out of the 100 “aborigines,” there are 31 children, principally half castes, at school, who are ‘fairly advanced’ and that “religious instruction is given to all daily.” And Manchester and Birmingham tourists of a commercial vein will, above all, be struck with the fact that in the account of receipts and expenditures at Coranderrk for 1884, there is a balance on the wrong side of £5,003 18s 5d! (The Argus, 23/5/1885).

In another newspaper article in 1885 James acknowledged that Coranderrk was a great attraction to visitors to Melbourne:

Picturesque Victoria: To Healesville

We pass the entrance to the station on the right. I have refused to again visit this native reserve. Eight years ago I was here with two young friends, now in France, and I gave my impressions of the place in The Vagabond Papers . I have also lately condemned the whole principle of the policy pursued towards our aboriginals in the carrying out of the system of reserves, which are principally occupied by half-castes, and I do not wish to be always harping on the same string. But Coranderrk is a great attraction to Melbourne visitors at Healesville, which is only two miles off (The Australasian, 30/5/1885).

5.9.3 The Vagabond’s 1893 Visit to Coranderrk

James returned to Coranderrk in 1893 – Joseph Shaw was now the superintendent.

HEALESVILLE. BY “THE VAGABOND,” IN THE LEADER .

Coranderrk is one of the first places the tourist at Healesville will visit. You can walk there and back and do the place in three hours. The number of full blooded blacks here is rapidly decreasing, although the board is trying hard to keep up the color by importing aboriginals from the Murray and the far western district. The reserve of 5000 acres was set aside for the nominal use of the old Yarra tribe. At the present time there is only one of these left, William Berwick, a very fine old man, known to many by Senor Loureiro’s magnificent painting, a Son of the Soil. The ordinary criticism on this picture was that it was not like an Australian aboriginal, the features being too good. That is true. The painting does not represent a type, but it is a wonderful study of William Berwick, who is the handsomest aboriginal I have ever seen, with Aryan profile and intelligent expression. The last of his race, king by descent, as he will tell you, is of a distinct type to other blackfellow I have seen in the length and breadth of Australia.

A new chum will be pleased with a visit to Coranderrk. When the old men strip off their European clothes and put themselves in fighting attitudes with spears and boomerangs in hand, the new chum will be thrilled. But they can throw neither spear nor boomerang. They have lost all their old arts, and have not acquired the industries of the whites. One can scarcely credit that they do not even make their own bread, which is supplied to the station from Healesville, Mr. Roberts being the contractor. The women make baskets of rushes, which the men sell in the township, and which are pleasing souvenirs for visitors to take them. But there is an old Tasmanian lives in the ranges who makes baskets of white wood, very superior to the native production. I but repeat now what I have written for years – that Coranderrk is a disgrace to the colony, land being locked here which should be utilised by white men. An effort is now being made to turn part of the reserve into a Village Settlement. But the whole reserve must be resumed by the Government or the last state will be worse than the first. The black fellows can be cleared away to the extensive reserves at Lake Tyers or Lake Wellington, where they can die off in idleness and dirt. I think William Berwick and his wife might be allowed to end their days on the spot where his ancestors were chiefs. At the present moment every man, woman, Coranderrk is kept at a cost of 200 acres of land per head locked up, and rations and clothes, and an expensive superintendence (Healesville Guardian, 29/12/1893).

McDonald (2014: 74) has noted that ‘James’s articles were highly controversial and drew a great many letters to the editor, both for and against’. In the case of Coranderrk his final article on the station elicited a response from a local Healesville woman, who had had enough of his negativity about the Aboriginal people of Coranderrk. Her letter also reveals the excitement in Healesville at the news of the impending visit of the Vagabond and the concern from local businesses that they needed to show him deference in case he wrote negative things about Healesville.

THE “VAGABOND” AND ABORIGINES. (To the Editor of The Guardian )

SIR,-Vagabonds are a class of people whom no honest and respectable person would like to associate with; but it was very amusing to see the state of excitement into which the inhabitants of Healesville were thrown a few days ago by the arrival of “The Vagabond.” My little boy came home from school, exclaiming – “Mother, the Vagabond’s in Healesville!” And to see the business people and others how they fluttered and hovered around him, knowing that unless they paid him some such homage, they would get a very poor advertisement if any. When he visited the bowling-green gentlemen of whom I would have expected better things – gave their subscription to get him a drink, because they did not wish to appear unsociable. Now, I am a woman, and my opinion of the “Vagabond” may go for very little; but I do think that he is a great coward. The unmanly way in which he attacks the aboriginals of Coranderrk, and the false witness he bears against them is mean and cowardly in the extreme. The “Vagabond” says that Coranderrk is a “disgrace to the colony; “I say it is a credit to the colony, and to the Government, that they have provided such a home for the aborigines (whose lands they occupy), that the men, women, and children might be protected from the drinking habits and the evil vices and influences of the white vagabonds who travel about the country. That the natives are naturally lazy is well known; but I venture to say that there is not a native at Coranderrk one bit more lazy than “The Vagabond,” and I know for a fact that more of Coranderrk natives have gone to the Murray district than have come from thence. I think if the “Vagabond” will only venture to visit Coranderrk that the native men – and women, too – will readily show him with what a steady hand and true aim they can throw the spear and wield the waddy. I am tired reading the same old story from the “Vagabond,” as it is all puff and rubbish. It is very unmanly indeed to write as he does against the poor aborigines. He does not seem to know that the natives cultivate a hop garden at Coranderrk, and that by their own industry alone they have succeeded in gaining the champion prize at the Royal Agricultural Show on several occasions, and that their hops have realised by far the highest price in the market. They also plough and sow, and carry on general farm operations, and their little village settlement may be regarded as a model of order and cleanliness. I challenge “The Vagabond” to prove anything to the contrary. His other remarks are unworthy of attention. Yours, &c., A WOMAN. December 19, 1893 (Healesville Guardian, 21/12/1893).

James’s writings often contain what Cannon (1969: v) has described as ‘philosophical homilies’ reflecting his ‘particular blend of liberal, conservative, free trade and anti-church views’ (Cannon, 1969: 5). He often expressed anti-Semitic and anti-Black views. The latter are seen in his writing about the Aboriginal people he met in Victoria. James shared the prevailing populist view that the Aboriginal race was destined for extinction as the savage ‘must disappear before the white man’. He believed the Aboriginal people ‘belonged to an inferior Stone Age race, destined to die out before the advance of a superior white race. This simple analysis was of a piece with his times’ (Cannon, 1981: xiii).

James promulgated the stereotype that Aboriginal people are lazy, indolent, and work-shy. He believed that children of mixed-descent should not be branded as ‘blacks’ but ‘given a chance in life away from the stupid and immoral influences of an aboriginal station’. He thought Coranderrk a ‘peculiar institution’, one that was simply a ‘government breeding establishment where the native and mixed races propagate in idleness’. Peck’s (2010: 217) assessment is that James was ‘naive about the effects of separating children from their families, and his opinion reflects the widespread doubts about the missionaries’ effectiveness in civilising Aborigines ...’. James also frowned upon the fact that the station occupied ‘valuable land near townships’ and considered a far better plan would be to send the Aboriginal people of Coranderrk ‘to those parts of Australia where game still abounds, and where the squatters would pay them for every kangaroo killed’. Another justification for removal was their underuse of the land – the earth belongs to those who will occupy and cultivate it’. He considered it was using valuable land close to Melbourne and his preference, if there had to be a government station, was that it should be up the country away from the temptations of white men. He characterised Coranderrk as a feeble attempt at civilising, and weak efforts at Christianising. He considered it ‘useless to attempt to artificially preserve the remains of a race never lovely in itself, and whose members have only learnt – and will only learn – the vices of the white man, and none of its virtues’. Although James was critical of Coranderrk and was an early advocate for its closure, he was more positive about the Lake Tyers mission station. Aboriginal villages, such as Lake Tyers, which represented a vision of an Aboriginal arcadia, combined the European agrarian ideal with aspects of traditional Aboriginal life such as fishing, and assumed the form of an idyll, a charming scene of rural peace. Lydon (2014) has noted that even the ‘hostile journalist’ John Stanley James ‘acknowledged this appeal in describing the picturesqueness of Aboriginal life on the Gippsland lakes’.

5.10 ‘Melbournensis’, Yering, and the Black Spur, January 1881

In 1881 in The Irish Monthly an article entitled ‘Yering and the Black Spur’ that mentioned Coranderrk was published by someone who used the nom de plume Melbournensis. Research by the author into the identity of Melbournensis has revealed he was the Rev. Michael J. Watson, S.J. (1845–1931).93 In 1911 he published a volume of historical sketches entitled The Story of Burke and Wills: with sketches and essays and in this work he included the sketch ‘In the Highlands, Victoria’ which is a verbatim copy of ‘Yering and the Black Spur’.

YERING AND THE BLACK SPUR VISITED BY MELBOURNENSIS.

During my stay in Yering I had the pleasure of making one of a party of excursionists to Fernshaw and the Black Spur. We set out early. Shortly after leaving the house we met a comfortably-dressed, good-looking aboriginal, on horseback. He belonged to the native station of Coranderrk, which is situated about a mile from the road which we were following. We put a few questions to “Tommy,’’ and received quick, intelligent answers (Watson, 1881: 42–46).

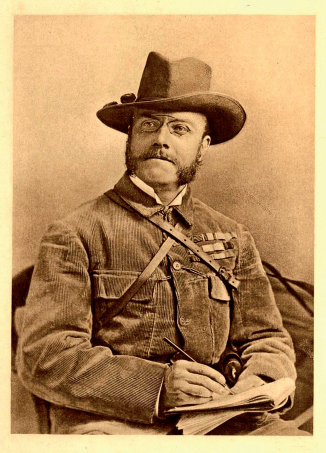

5.11 Melton Prior and Coranderrk, January 1888

Melton Prior, a ‘Special Artist’ and war correspondent for the Illustrated London News from the early 1870s until 1904, reported in its 12 January 1889 issue that he had recently visited Coranderrk. Prior had come to Melbourne to make sketches of the 1888 Melbourne Centennial International Exhibition (Daily Alta California, 30/5/1888).94 In September 1888, the Geelong Advertiser reported on Prior’s activities in Australia:

The readers of the Illustrated London News must be familiar with the graphic sketches from the pencil of Mr Melton Prior, who for nearly two decades has acted as special artist of that journal in every one of the wars which have taken place during that period. Mr Melton Prior has been on a professional visit to Melbourne for two months past, for the purpose of sketching Melbourne during the Centennial Exhibition period. He has been asked to deliver a series of lectures in Melbourne and the provinces, and has consented. He will lecture in the town halls of Melbourne, Geelong, Ballarat, and Sandhurst at an early date, and his lectures will include his war experiences, illustrated by panoramic sketches from his own pencil, done on the field of battle (Geelong Advertiser, 13/9/1888).

Prior confirmed the tourist trade enjoyed by the Aboriginal residents – the women made fancy articles, such as the feather aprons used in ‘olden times’ or baskets and nets, and these articles may be purchased by visitors to Coranderrk. The men were allowed to manufacture and sell boomerangs. Prior was entertained by displays of boomerang throwing and an old man showed him how to make a fire with two pieces of wood and dry bark. Prior observed the ‘natives here collected live in comparative comfort, with very little work to do; hop-growing being of the principal employments’, and noted that ‘To say they are happy in this confined condition would not be true’.

Figure 5.2: Melton Prior.95

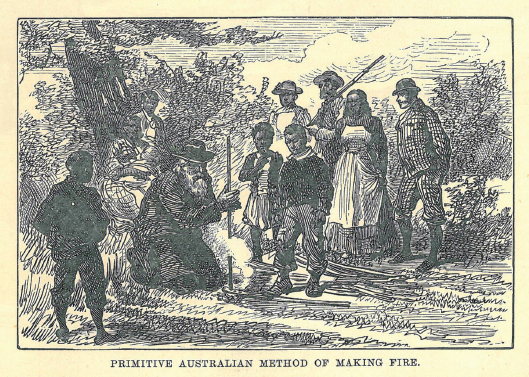

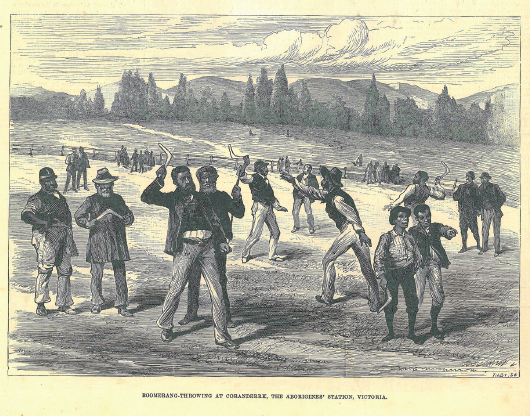

Three Prior sketches of scenes at Coranderrk were reproduced in The Illustrated London News : one showing the primitive Australian method of making fire which depicts tourists standing around an elderly Aboriginal man as he makes a fire (see Figure 5.3). The second depicts the main street of the station and is entitled ‘Street of Coranderrk, the Aborigines’ Station, Victoria (see Figure 5.4).96 The third is a scene on the oval entitled ‘Boomerang-Throwing at Coranderrk, the Aborigines’ Station, Victoria,’ and shows groups of tourists watching Aboriginal men throwing boomerangs (see Figure 5.5).97

Figure 5.3: ‘Primitive Australian method of making fire’. By our special artist, Mr. Melton Prior. (Source: The Illustrated London News, 12/1/1889, p. 51).

Entitled ‘Sketches in Australia – By Our Special Artist, Mr. Melton Prior’, the article in The Illustrated London News, explained that ‘Our Special Artist, Mr. Melton Prior, during his recent sojourn at Melbourne, the capital of the Colony of Victoria, had an opportunity of visiting the Government station for the residence of protected aborigines, which is situated at a place called Coranderrk, in the hill country beyond Lilydale, a small town or village of about four thousand inhabitants on the railway twenty-four miles north-east of Melbourne’.

We proceed to give our Special Artist’s own account of his excursion to the Coranderrk Aborigines’ Station, and of the road to that place, which is from Lilydale, he says,” a perfect slough of despond,” at least in the season of the year when he performed the journey …

Figure 5.4: ‘Street of Coranderrk, the Aborigines’ Station, Victoria’. By our special artist, Mr. Melton Prior. (Source: The Illustrated London News, 12/1/1889, p. 51).

Figure 5.5: ‘Boomerang-Throwing at Coranderrk, the Aborigines’ Station, Victoria’. By our special artist, Mr. Melton Prior. (Source: The Illustrated London News, 12/1/1889, p. 52).

“We soon arrive, therefore, at the gates of Coranderrk Station, one of the reserves provided by Government for the remnants of Australian aborigines. It is a large tract of land, over 4000 acres. The natives here collected live in comparative comfort, with very little work to do; hop-growing being one of the principal employments. To say they are happy in this confined condition would not be true; but they are watched over by a gentleman, Mr. Shaw, who does his utmost both in careful superintendence and by his friendly manner, to render their restraint more tolerable; and he seems to have gained the goodwill of the unfortunate people, who are fast being thinned by age and disease.

“A good deal of work is got through at times, the women being expert with the needle in making fancy articles, such as the feather aprons used by the natives in olden times, or baskets and nets; and these articles may be purchased by visitors to Coranderrk. The men are allowed to go out hunting occasionally; but one of their chief amusements is the making and throwing of boomerangs, which they also are allowed to sell. Great care and skill are necessary in their manufacture, to ensure the peculiar flight of these strange missile weapons through the air.

“I chanced to be there in the evening when the men, young and old, were out practising with boomerangs and trying them; and I was much astonished by the extraordinary style in which, being thrown with great force, the boomerang would whirl through the air, looking like a hoop; then, after rising and falling, and swooping about in the manner of a bird, it would return and fall at the thrower’s feet. The children and boys were running to and fro, picking up the fallen implement as it fell; whilst the wives and sisters were looking on at a distance.

“For the second time in my life, I here also saw an old native make fire with two pieces of wood. One piece of wood rests on the ground, over some very dry bark of a tree, and then, with a long stick put between the hands, a certain twist is given, not so much by force as by knack, till the two pieces of wood emit sparks, which ignite the dry bark, and there is the fire. The whole process does not take more than half a minute. Novices may try their hands at it, but with as much success as in throwing the boomerang, for great practice and skill are necessary in both operations.”

5.12 A Cricket Match: Coranderrk versus St John’s Cricket Club, November 1892

This next article concerns a cricket match at Coranderrk station between St John’s Cricket Club from Williamstown and an Aboriginal team from Coranderrk. The day’s proceedings were organized by the Coranderrk school teacher Edwards. Before the game commenced, the tourists were treated to an exhibition of boomerang throwing and several of them tried their hand at throwing. After the game which was won by the visitors some of the cricketers visited the station and inspected the residences at Coranderrk, others went fern gathering.

A TRIP TO CORANDERRK (By One of the Party)

ANXIOUS to spend Prince of Wales’ Birthday in the peaceful stillness of the country, away from the humdrum and busy activity of city life, the members of the St. John’s Cricket Club arranged – through the kind offices of Mr Edwards, school teacher at the Coranderrk station – a match for that day with the native team of that place. The contingent, who left Footscray by the 6.29 train, numbered 11. We hurried down from Spencer street to Princes Bridge station, for the train to Healesville was timed to leave the latter station at seven o’clock. We got down in good time, but had a mighty struggle to get the tickets. … However, we, the members of St John’s, safely ensconced ourselves in a first-class carriage; and all went well. We had a merry trip to Healesville, which station we reached at a quarter past nine. There we were duly met by Mr Tresize, a prominent member of the Healesville Football and Cricket club, a former acquaintance of the writer, and one to whom we were much indebted for kindness received during the day.

There also were buggies driven by two of our sable opponents; Tom Dunolly and Billy Russell. Into the vehicles we got, and were driven out to Coranderrk, about two and a half miles away. It was a lovely drive through the bush, and one could not help thinking how true the line of the poet, “God made the country, but man made the town.”98 The picturesqueness of Coranderrk station has been described in other journals by abler pens than mine; suffice it for me to say that it is a beautifully situated spot, and one that delighted the eyes of all of our team.

We were driven to Mr Edwards’ house, where we were warmly welcomed by Mrs and the Misses Edwards, Mr Edwards, whom we would have liked to have personally thanked for having arranged the match, having gone to Melbourne to battle on behalf of the Healesville Bowling Club with Princes Park Club. Coming up in the train we had been recounting to each other our varied experiences that morning about getting our own breakfast. In some cases the fire would not light, in others the kettle was put on with no water in it, and some had just time to rush for the train. In a word we were hungry, but we never expected to find such an excellent breakfast ready for us on our arrival at Coranderrk. Yes. Mrs and the Misses Edwards’ had prepared for us a sumptuous repast, which was done full justice to. After breakfast our fellows were treated to a splendid exhibition of boomerang throwing by the natives. A few of our contingent essayed the task of throwing them, but narrowly escaping killing a few of their comrades they gave up the attempt, and contented themselves with watching the wonderful way in which Jack Friday and Billy Russell made the weapons perform. Some of our team were anxious for tennis on the morning, but our opponents advised making an early start at cricket, as they prognosticated rain would commence about four o’clock. We took their advice and commenced about eleven. A really excellent wicket had been prepared, and when our captain, George Cuming, won the toss from Tom Dunolly who commanded our opponents, he decided to bat. The bowling of Dunolly and McLellan was so good that the first five of our wickets fell very rapidly, but thanks to vigorous cricket by A. Scott, and H. Dobbie, and a careful innings by T. Handfield, the innings reached 81 runs before the last wicket fell. Dunolly and McLellan bowled right throughout the innings and shaped splendidly, especially the former, who trundled with extreme hard luck, several catches being missed off his bowling. W. Shaw and H. Scott started the bowling for St John’s, and both being in good form, the wickets fell rapidly until Foster came in to bat. He commenced trilling in brilliant style, and caused Scott to retire in favor of Dobbie. Eventually the innings closed for 47, out of which number Foster made 18. We were then entertained to an alfresco luncheon by our opponents, who had provided a tempting lot of eatables, which, after our two hours play, were much enjoyed. After smoke-oh, cricket was resumed by our captain sending our opponents again to the wickets. On the second essay they made 54, Foster again batting vigorously. Fortunate we were in the first innings in getting rid of Dunolly, the skipper, so cushy, as he is an excellent batsman. We were left 21 to get to win, and Handfield and H. Scott were sent in to make them, and succeeded in doing so, the latter batsman scoring 19 by free cricket and was caught in the long field just as the requisite number had been made. This ended the game. The cheers which we gave our opponents at the conclusion were hearty, for it was one of the most pleasant games we had ever played. Our opponents were as jolly and amiable a set of cricketers as one could meet, and their captain showed that he was the right man in the right place. Better fielding than that of Harrison, one of our antagonists is very seldom witnessed, and the umpiring of Mr Tresize and Bobby Wandon gave satisfaction to everybody. About 3.30 cricket was over, and we put in the rest of the afternoon in various ways. Some played tennis, others inspected the well-kept station, and visited the residences of the blacks, whilst a few went fern gathering and came home laden with a splendid lot of maiden hair and wild flowers. True to the blacks’ prediction rain commenced to fall about 4.30. Tea was then provided by Mrs Edwards, and about seven o’clock we were driven to Healesville to catch the train, but before leaving gave three hearty cheers for Mrs and the Misses Edwards for their very great kindness to us during the day. The rain was coming down in torrents as we drove through the bush to Healesville. But what cared we for that? We had spent a most enjoyable day, and it would take more than a good wetting to damp the ardour of our spirits. I cannot conclude this crude account of our trip without mentioning the name of Jack Friday, one of our opponents. Will any one of us ever forget his merry laugh, and his really witty sayings? I trow not. On the return journey to Melbourne we had his company, as he went to Melbourne for a day. What a splendid lot of songs he sang for us. Poor old Jack! May his shadow never grow less (He is only 16 stone) (Independent, 19/11/1892).

5.13 A Camping Holiday on the Coranderrk Creek, January 1894

In January 1894 a party of friends went to Healesville for a camping holiday at Christmas on Coranderrk Creek. The members of the party were called ‘the Professor, the Volunteer, the Grub, the Grumbler, the Wombat, and the Irrepressible’. During their holiday they visited the Coranderrk Aboriginal station:

A HOLIDAY AT HEALESVILLE. CAMPING ON THE CORANDERRK. [BY A.J.]

The trip to see the Coranderrk blacks was made on a fine day, and I went. The rain never stopped our boys! There is not a great deal to see at the station pure and simple. You have to make your own fun there. Boomerang throwing is all very well in its way and was interesting to me, but what the crowd I was with did not know and had not seen seemed infinitesimally small. The Grub knew something about black fellows, got the chief of a tribe (whose name I forget)99 to express his conception of “love.” At first the task appeared hopeless, but a little whisper advanced matters considerably. The next instant the erstwhile leader of his mob had tucked the Grub in the ribs, was chuckling most peculiarly, and saying the Grub knew all about it. I had always believed the black fellow had nothing but animality in his economy, but this gentleman listened with wrapt attention while the Grub recited portions of Shelly’s “Rosalind” and “Helen,” and Philip Marston’s “Before the Battle.” The Professor afterwards dwelt at length on the atomic or some similar theory, and showed how this man, who had been selected for a chief, probably was so constituted to have far more intelligence than the common or garden black. We all liked listening to the Professor when he had it bad; there was a gladsome relief when he finished, not to be obtained otherwise. However, a sensitive photograph would be the thing to reproduce this scene, and as that was not at hand, anybody who wants to hear the Chief of all the Yarras, or of whatever clan it was he bossed before the white man spread over Victoria, had better take out the Grub to get the old chap on the job again. The Volunteer endeavoured to obtain a sketch of the old boy’s warrior days, but this was a failure. Except that in action the sky was not seen for spears, we learned nothing (Healesville Guardian, 5/1/1894).

5.14 ‘Amongst the Black Fellows’ by J.D.C., November 1911

This is an interesting article as it reveals the context in which the Aboriginal residents of Coranderrk expected to interact with tourists – with dignity and formal introductions. One white female tourist who was looking at a little baby was quickly told by the child’s mother that ‘her staring and gazing at the tiny black piccaninny was not quite becoming [of] a lady’.

“Amongst the Blackfellows!” Such an opportunity fell to my lot on Boxing Day holiday, when I paid a visit to Healesville. Here there was a bicycle sports meeting held, and it was attended by the Australian aboriginals, or what is left of them, who are homed at what is known as the Coronderrk [sic] Station. There were old blacks and young blacks, married blacks with their wives and families, some of the latter in arms, others toddling hither and thither, of varied ages and both sexes. Certainly, all told, the number was not great. They comprise the handful left to remind their whiter-skinned brethren who it was who formerly held sway and possession of that portion of Australia known as Victoria. Your blackfellow and black woman, of course – of today, are a highly civilised class, and don’t you forget it! Undeniably, however, as a people, they are still aboriginals. With their high cheek bones, eyes large and gleaming, that appear to scan the country for innumerable miles at a glance, jet black hair, and holding their still beloved boomerang and fire stick, they don’t fail to give one the impression that they are what they are descendants of the old and original stock. In their dress, which, truth to tell, is moulded in the rough, they make brave attempts to imitate the attire of their European brothers and sisters. As for the ladies, one cannot say that he noticed an ideal hobble skirt or bucket hat. Possibly that is a circumstance that can be put down to the credit of the female aboriginals. They appeared to appreciate comfort rather than any absolute style that may have emanated from Paris, for their costumes were ideally appropriate to the warm weather that prevailed, even though the fitting was not entirely accurate in parts. Your black lady and gentleman deport themselves with every ounce of dignity at their command, and anyone who attempts to strike up a conversation with them without the formality of an introduction, in the majority of cases soon finds this out. A black woman, for instance, was nursing a piccaninny an interesting little creature to gaze upon. A white woman, out of excusable curiosity, kept on eyeing the little one and watching its antics. The mother just as keenly now and again eyed the white woman, and losing patience, informed her in perfect English pronunciation and enunciation to the effect that her staring and gazing at the tiny black piccaninny was not quite becoming a lady. The white woman wasn’t slow at taking the hint! I had the good fortune to drop across one interesting old blackfellow. He was none other than King Anthony Anderson, of Birchip, Donald, and two or three other places. This information is contained on a brass oval plate which “His Majesty” wears around his neck. The plate was said to have been sent out to Anthony by the present King when Duke of York. Amongst people who speak in the familiar style King Anthony is known as “Tony”. “Tony’s” exact age is unknown, but it is reckoned to be anything between 50 and 100, or over. At all events, there is no more genial soul alive than “Tony”. He is a humorist, too, in his way. Likewise his style of conversation is quite taking. I had a word with “Tony.” I felt quite honored.

The blackfellows took a very keen interest in the bicycle sports. In addition, there was a boomerang throwing competition for the blacks. By way of preliminary a white man – one of the sports officials – tried his hand at the game. He threw a boomerang, it took a terribly erratic course in endeavouring to return, and as a finale it struck an elderly blackfellow on the face and knocked his pipe out of his mouth! The crowd roared with laughter; but the blackfellow simply picked up his pipe as if experiences of this kind were every-day occurrences to him! It is no awe-inspiring spectacle to see the present day black throw his boomerang. With a slight curve of the body, to the right and to the rear, the old time implement of war is thrown with apparently little impetus, and less ceremony. Away it goes in a circle at first sight looking like a bird on the wing, and if it comes right back to the feet of the thrower so much the better for the dexterity of the thrower. An elderly and a young black engaged in a fire-stick competition. With the point of the stick held against a piece of wood the fire is lighted by the friction, i.e., by whirling the stick backwards and forwards between both hands. A small piece of inflammable material is close to the point of the stick ready to catch the first spark, and when this, is done the material is picked up and the spark coaxed into a flame by using the mouth as a bellows. The old black blew soft and hard alternately, but the result was only smoke. The younger competitor, amidst applause, was the first to produce the flame. The old fellow had had bad luck and in his case, at least, a maxim of the whites, that where there’s smoke there’s fire, did not hold good. Some of the blacks also took part in the greasy pig competition, which a dozen or so whites also participated. Piggy, although he had his tail greased, had a very short run. The crowd was upon him in quick time, and when all was over a blackfellow emerged carrying the squealing pig on his shoulder. He had proved victorious, but the result did not cause as much world-wide interest as when Mr Jack Johnson, the gentleman of color, knocked out the “hope of the white race” in the person of Mr Jim Jeffries. That civilisation was firmly implanted in the breasts of the Healesville black fellows was proved by the fact that they are quite prepared to make a bargain where the coin of the realm is concerned, as the winner of the contest immediately sold the pig for 15/-. The sports over, the blacks strolled out of the ground at intervals to return homewards, and as the shades of evening were failing fast the sounds of “coo-ee” fell upon one’s ears. This made me feel more than ever that I was indeed “Amongst the Blackfellows!” (Malvern Standard, 21/11/1911).

5.15 A Picnic at Coranderrk, March 1914

In March 1914 a lady visitor to Coranderrk contributed presents and gifts to the Coranderrk residents for their annual picnic. It is an interesting article in that it shows the activities the residents enjoyed when they were spending quality community time together, including boomerang throwing, fire making competition, basket making competition, various foot races, and a tug of war. At the end of proceedings three men sang and performed a corroboree.

Picnic at Coranderrk (Contributed.) Thursday, March 26.

The day was all that could he desired for picnicking, though John Blair and “Lanky” Manton thought that the wind would hazard and spoil good boomerang throwing. Just after lunch men and maids, old and young, began to gather from the camps on the bank of the Yarra Yarra and from the homes on the hills. How nice and smart they all looked-evidence of care is not wanting. Modestly and cleanly attired little ones shyly waited their turn in the day’s sport. Said a lady visitor: Do the folk at Coranderrk have an annual picnic? We do not need to go into details, this is enough, that this lady sent along many little presents of value, another also sent a few gifts, so the superintendent and his good wife did the catering, and a few friends came to help the day’s sport. “Lanky” Manton let Russell fix the peg for the boomerang throwing. “Lanky’s” first throw arrived [...] yards and a half away, and the other seven competitors could not beat it. Then the fire making was another interesting display. Everybody thought that Henry McCrae was going to win, but his bark was too new. “Lanky,” who had failed, again tried and finished second to Alex McCrae, who had had two tries. In this and the former event the prizes were two tobacco pouches and pipes and one knife. The tug-of-war was most exciting, but the married men held their own throughout, and smiled upon five pipes. The old women competed in basket making, five minutes commencement of the basket. Jemima Dunolly was first, and Ellen Terrick beat Ellen Richards for second place. The married women’s race was well handicapped, and Mrs Kate Mullett, just beat Mrs Mary McCrae, who had five others closely in pursuit. The young women very shyly contested, and Jessie Wandin just won by a foot from Mary McCrae. In this and the foregoing event, the prizes were two lace collars and two nice necklaces. Daisy Davis, with a happy smile, was to be seen with her new skipping rope, signally her success, while four little girls, two with books, one with a ball, and one with a necklace, quietly brought their winnings to their mother. Campbell and Freddie Mullett had a good run for a book and a trumpet. The usual votes of thanks were moved and hearty cheers accorded after the replenishing of the inner man; then Russell, “Lanky” and John sang and did a corroboree. Eyes turned to the west where a rich copper glow like a posthumous veil eclipsed the sun, and a quiet murmur passed from soul to soul watch out tomorrow. Happy, laughing folk cheered lustily while they watched the champion runner of the station beat the best runner among the single men. Other nice gifts of texts and two bibles were distributed, and another lady visitor gave each little one a prize packet, or a sweet stick. Little Teddy is three years old, no one beat him for the drum – he beats it as his father carries him up the hill to the station. The rain came! (Healesville and Yarra Glen Guardian, 27/3/1914).

5.16 ‘How Would You Like To Be Forced to Move to Germany?’ January 1918

One of the most striking instances of a Coranderrk resident taking advantage of a visitor to their station to advance their political interests and make clear protests about their situation is that of the interaction of Benjamin ‘Lanky’ Manton, erroneously referred to in the articles as ‘Mankey’ and his reaction to the latest push from the Board to close Coranderrk and relocate its residents to Lake Tyers Aboriginal station. The writer, identified as C.C., notes that the ‘veteran aborigine, is an extraordinarily emotional being’ that ‘can be studied at the Coranderrk station’.

THE LAST OF THE TRIBES. (By C.C. in Melbourne “Age.”)

He crouches and buries his face on his knees.

And hides in the dark of his hair;

For he cannot look up to the storm smitten trees.

Or think of the loneliness there;

Of the loss and the loneliness there.

Kendall wrote his poem, “The Last of His Tribe,” fifty years ago, but a few members of the aboriginal race still linger. The poet scorned realism and gave rein to his delicate fancy. While the veteran aborigine is an extraordinarily emotional being, he is not given to dreaming sadly of the days that have flown or of the “honey-voiced woman.” who watched “like a mourner for him.” He can be studied at the Coranderrk station. Despite his frequent contention that his allowance of one pound of fresh beef per day – double the ration given to the soldier at the battle front – is a wretchedly inadequate meat supply, he laughs as often and as heartily as any other person in the Commonwealth.