Providing meaningful information: Part A—Beyond the search

Diana Delgado; Michelle Demetres Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, United States

Abstract

This chapter introduces scholarly publication and the informationst's role in supporting researchers embarking on this journey. It breaks down the scholarly communications lifecycle into three sections and illustrates techniques on how the informationist may assist in each stage. The Pre-Pre-Publishing section covers establishing a good research project, focusing the question, appropriate format for topic, reaching the target audience, authorship, and filing for patents. Pre-Publishing covers topics such as literature review, trustworthiness, determining publisher/sponsor longevity, pros and cons of impact factors, visibility/reach, open access considerations, and acceptance rate/time to publication. The Publishing: Navigating the submission process section, focuses on assisting the researcher with the “Instructions for authors,” choosing Keywords/subject headings, Copyright, and Open researcher and contributor ID (ORCID). The last section is a case study where assistance by an informationist is provided to a researcher whose manuscript has been returned by reviewers with a request for extensive edits.

Keywords

Scholarly publishing; Scholarly communication; Pre-Publication; Publishing; Copyright; Informationist

3.1 Introduction

Contributing to scholarly communication is a requirement for many members of the medical and academic fields. This expectation now extends to many professionals who have little experience with the scholarly publishing process. As Rowan Murray predicted in the text Writing for Academic Journals, “the pressure on academics to publish in journals increases year by year. In addition, as more institutions are granted university status, and new disciplines join higher education, there is an urgent need for support in this area” (Murray, 2005). An informationist's involvement often begins at the literature search. Owing to the nature of our profession, we are often best suited to help a researcher take the analysis that goes into a research project, and help them present this to peers and advance their careers. Therefore, it is important for informationists to be well versed in the ins-and-outs of publishing, as the lifecycle of a researcher's literature search might end in publication.

3.2 Pre-pre-publishing: Getting started

Before the pre-publishing process can begin, there are several questions the informationist should ask the researcher. Nailing down the following will determine which direction the researcher should take, or whether or not they should pursue publication at all.

3.2.1 What do you have to say?

Developing a well-defined and well-thought-out topic is essential before beginning any steps in the writing or publishing process. Starting with a well-articulated idea will help dictate the direction the researcher will take in all the steps that follow. Using the PICO(T) model for clinical questions (Table 3.1) is a great way to map out an idea.

Table 3.1

| P | Population/patient | Can be individuals diagnosed with a certain disease, age group, gender, ethnicity, etc. |

| I | Intervention/indicator | This is the variable of interest. This can include a drug or surgical treatment, exposure to disease, risk behavior, etc. |

| C | Comparator/control | Includes placebo, absence of risk factor, standard of care, etc. |

| O | Outcome | Measureable evidence such as desired/undesired effects, survival/mortality rates |

| T | Time | Length of observation or intervention |

Based on Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club, 123(3), A12–A13.

The importance of developing an outline or protocol seems to go without saying, but making sure you convey this to the researcher will save innumerable headaches as the writing process progresses. This is especially important in long-term projects, where it is easy to lose track of where you've been, or where you are going. As the informationist is there at the beginning of the research process with the literature search, helping the researcher develop their writing in a robust and organized way is the first step toward successful publication.

3.2.2 Is the paper worth writing?

Using the FINER (feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, and relevant) criteria for a good research question (Table 3.2) is a good way to determine if the idea is worth pursuing (Pirmez, Brandao, & Momen, 2016). It helps the researcher to find out if there is already similar information or conclusions available on the topic before they begin. Having a unique point of view is important for work to be accepted to a scholarly journal. Will this article be redundant in regards to the available scholarly literature? All submitted work must be original, and if the same conclusions (while not technically plagiarism) are found elsewhere, the article will most likely not be accepted. This includes work that the researcher may have already published. It is also important to explain to the researcher that, ethically, they should publish in the “smallest publishable unit.” This means that it is considered unethical to break up research that logically belongs in the same articles in order to try and get more published work, also known as “salami slicing.”

Table 3.2

| (F)easible | ||

| Is it feasible? | Research idea/study plan | Are there enough subjects (eligible and willing)? Do you have the required technical expertise? Do you have access to the required resources? |

| Publishing | Have you or anyone on your team published before? Do you have time to write the manuscript? If rejected by first choice journal do you have time to submit to second choice journal? | |

| (I)nteresting | ||

| Is it interesting? | Research idea | Do you have passion for it? Do others? |

| Publishing | Will it be interesting for you/your team and readership? Are there like-minded researchers that you may consider reaching out to coauthor with? | |

| (N)ovel | ||

| Is it novel? | Research idea | Is it a new research idea? Are you in some way contributing new information or findings to the field? |

| Publishing | Have you conducted a literature review to determine if the topic is novel? How does your work differ from previous publications? | |

| (E)thical | ||

| Is it ethical? | Research idea | How will you handle informed consent, anonymity and confidentiality? Has the study been approved by the institutional review board? |

| Publishing | Does the work salami slice, plagiarize? Have all contributors been properly credited via authorship or acknowledgment? | |

| (R)elevant | ||

| Is it relevant? | Research idea | Will your work have impact on scientific knowledge, clinical practice, or policy? |

| Publishing | Where will you submit your manuscript to? Consider where your paper will have the greatest impact (scientific knowledge, clinical practice, or policy) Does the journal accept your manuscript format? Who is your target audience? Is your target audience the journal’s readership? Will your work be discoverable? Where it is journal indexed? | |

Here, we have adapted the bare bone principles of FINER (Pirmez et al., 2016) and applied them not just to research idea development, but for publishing considerations as well.

3.2.3 What format is appropriate?

There are many different formats that published work can take. Some examples include: review articles, editorials, case report, letter to the editor, books or book chapters, conference abstracts, and poster presentations. It is important to remind the researcher that each format has its own rules for structure, and not all journals will accept all formats.

3.2.4 Who is your audience?

Determining who will be reading the article can help decide where the researcher should publish, as different journals will have different reach and readership. For example, an article addressing nurses should be published in a journal that nurses read. Audience can also influence the tone of the writing.

3.2.5 Who will be credited as an author?

Defining who will be credited as an author and in what capacity (first author? last author? and corresponding author?) is important to tackle at the beginning of the process. In their 2016 report, the ICMJE recommends that authorship should be based on the following four criteria:

- 1. Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work.

- 2. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

- 3. Final approval of the version to be published.

- 4. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved (ICMJE, 2016).

Also, be sure to remind the researcher that all authors involved in a manuscript must provide full disclosure. This includes conflicts of interest (are any of the authors employed by a company that might benefit from the article’s publication?) or any sources that provided funding for the work, including grants.

3.2.6 Do you plan on filing for a patent using this work?

It is important to inform the researcher about patent laws if the work they intend to publish involves an invention or patentable entity. If they are planning to obtain legal rights from the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) via patent application, there are certain regulations of which they should be aware.

Under US patent law, “a person is entitled to a patent unless, among other things, the invention has already been patented or described in a printed publication or is otherwise available to the public before the filing date of the patent application that claims the invention (Title 35 U.S. Code sec. 102(a)(1))” (Reed, 2013). This means that if the patent was previously publically disclosed, the researcher's application will be rejected. Disclosure can include written and oral disclosure, including (but not limited to) journal articles, theses, or public seminars. The idea of “public disclosure” gets a little vague when it comes to grant proposals or meeting abstracts. If the disclosure is “not sufficiently detailed to actually enable someone to make your invention, then that disclosure may not harm your chances of getting a patent” (Mohan-Ram, 2001).

An informationist should inform the researcher that she need not wait until the application has been accepted or rejected for publication. “[A]fter merely filing the patent application, the applicant is free to publicly disclose any aspect of the invention that is covered in the patent application, even though the application may be years away from grant”(Reed, 2013). So, most likely the researcher would want to first apply for patent, and publish later.

3.3 Pre-publishing: Choosing the right journal

A major part of assisting a researcher in getting their work published is determining where to do so. As, ethically, a researcher can only submit an article to one journal at a given time, it is important to choose one that is appropriate. Remind the researcher that simultaneous submission is considered unethical. If an article is rejected by a journal, they can, and should, revise and resubmit it elsewhere, but they must receive a rejection notification first. Bhandarkar (2013) outlines a list of dos and don'ts for authors to avoid misconduct:

- 1. Never submit the same manuscript to more than one journal simultaneously.

- 2. If a manuscript that is under peer review of one journal is to be submitted to another journal:

- a. Inform the coauthors and get their written consent.

- b. Write to the Editor of the first journal, asking that the paper be withdrawn.

- c. Get a formal communication from the Editor of the first journal that the article has been withdrawn from peer review process.

- d. If such a communication is not received, do not submit the manuscript to another journal.

- e. Preserve this communication and submit it to the second journal at the time of submission (Bhandarkar, 2013).

Here are a few steps to help them vet the many options, ideally coming up with a list of three target journals. Remind the researchers that these criteria should be looked at collectively in order to get a complete picture.

- 1. Search to see where similar papers have been published. What some authors fail to realize is that they have already developed a list of potential journals by the time they have finished the manuscript—their bibliography. Chances are there will be several articles published in the same journals, providing a good place to start investigating.

- 2. Do you read it/trust it? Do your colleagues? A researcher wants their article to make the most impact possible, so the more widely read/known the journal, the better. If the author or their colleagues have never heard of a journal, there is a chance it might be producing less-than-quality content. Firsthand experience with a particular journal is invaluable, so it helps to have the researcher talk to other authors who have published in a particular journal. Trustworthiness can also be evaluated through author/editor credentials. Have the researcher check out the editorial board. A journal’s editors should ideally be known, international experts in the field. Having an international board helps to reduce bias, and can help to recognize the best research from all over the world.

- 3. Who is the publisher/sponsor? Is it a society journal? A recognizable publisher name or society is a good indicator that a journal is trustworthy. Since there is money to be made in publishing, many predatory journals have cropped up, scamming authors with high publishing fees. These are strictly for-profit operations, wherein published papers do not undergo any peer review or quality control, despite being advertised as such.

- 4. Longevity—How many volumes has the journal published? Longer running journals can typically be considered more trustworthy than journals with shorter runs. If a journal has been around for a while, it is usually for good reason.

- 5. Impact factor of journals in the field. Many researchers will look at the impact factor and make a decision based on this metric alone. This is ill-advised and the informationist should let the author know that impact factor should only be one part of the whole when deciding where to publish. Impact factors were designed with the idea of managing library journal collections, as they were deemed helpful in “determining the optimum makeup of both special and general collections”(Garfield, 1972). As Pirmez et al. point out, “things can get more complicated when this metric is deployed to measure and define what is beyond its natural limits” (Pirmez et al., 2016).

- 6. Where is the journal indexed? Have the author take a look at visibility/reach. In which databases is it available—MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, etc.? Explain that if an author wants their article to get the best possible exposure for maximum readership, then a widely indexed journal is an important factor.

- 7. Is the journal open access? If a journal is open access, it means that the content is freely accessible for readers, without subscription costs or paywalls. Often times, funding bodies will have open access requirements that accompany their grants. It is important for the researcher to know their open access obligations before choosing a journal.

Remind the author that just because an open access journal means there are no fees for the reader, this does not mean that there are no fees for them. Often times, publishing in an open access journal will be contingent upon APCs or Article Processing Costs/Charges. These can be anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars, and vary from journal to journal. Sometimes these fees are covered by research grants. Some institutions will also have APC reimbursement funds, so it is important for informationist to be familiar with the options available at their institution. - 8. What is the journal’s acceptance rate? Time to publication. This will help authors get an idea of what they are in for once they have submitted an article for publication. First time authors are often unaware of how long the process can take, even just to get a rejection letter.

Other than information provided on the journal’s homepage, there are several tools an informationist can point authors to in order to answer these questions. Table 3.3 can be used as a guide.

Table 3.3

| Resource | What you'll find |

|---|---|

| JANE (Journal/Author Name Estimator)—Free | A freely available Web-based tool to identify suitable journals. Simply copy and paste your abstract into the search box, and JANE will then compare your document to millions of documents in Medline to find the best matching journals, authors, or articles |

| PubsHub—Subscription only | A variety of information for clinicians and scientists who are trying to determine where to publish or present their research. Covering over 3400 biomedical publications, the PubsHub database contains details on journal impact factors, acceptance rates, publication turnaround times, MEDLINE indexing, and more. For researchers interested in presenting works at conferences, PubsHub provides details such as number of attendees, upcoming dates and locations, and whether abstracts are published, for more than 2000 conferences. Particularly helpful with acceptance rates and publication timelines |

| Journal Citation Reports—Subscription only | The current standard for impact factors, using citation data drawn from over 8400 scholarly and technical journals worldwide. Coverage is both multidisciplinary and international, and incorporates journals from over 3000 publishers in 60 nations. Contains citation data on journals, and includes virtually all specialties in the areas of science, technology, and the social sciences. JCR Web shows the relationship between citing and cited journals. Search by journal title or broad discipline |

| Ulrich’s Web—Subscription only | Bibliographic and access information about serials published throughout the world, covering all subjects. Entries provide pricing, subscription, and distribution details as well as publisher and editor contacts. Direct links to URLs and e-mail addresses given when available, along with reviews excerpted from Magazines for Libraries and Library Journal. This is a particularly good resource for indexing information |

| SHERPA/RoMEO—Free | RoMEO is part of SHERPA Services based at the University of Nottingham, and is a regularly updated database of journal's copyright policies. Helpful for determining open access policies and procedures |

| Scopus—Subscription only | Compare journals by: SJR (SCImago Journal Rank—weighted by the prestige of a journal), IPP (Impact per Publication—ratio of citations per article published in a journal), SNIP (Source Normalized Impact per Paper—measures a source’s contextual citation impact), Citations, Documents, % of Not Cited, and % of Reviews |

3.4 Publishing: Navigating the submission process

3.4.1 Instructions for authors

An “Instructions for Authors” page will often address many of the researcher's questions about their target journals. You can usually find them on a journal’s homepage. Each journal will have different requirements, therefore it is important to follow each journal’s specifications carefully. These will often include information on the following:

- ● How to format the article and abstract, including word count, required headings, etc.

- ● The instructions page should identify what types of articles are accepted; not all journals will accept all types of articles.

- ● How to format illustrations and figures.

- ● Publishing agreements, including the self-archiving policy and copyright terms.

3.4.2 Keywords

Some journals will require authors to provide keywords or subject headings for their articles. As an informationist with a keen knowledge of the importance of keywords for findability, we are uniquely suited to help in this regard. Let authors know that this is how their peers will find their article in a literature search, and that a wider audience generally leads to more citations. Warn about keywords that are too broad, and to be sure to use the maximum number of keywords allowed by the publisher.

Some publishers specify the vocabulary to be used, such as MeSH. If they are having difficulty in choosing terms, search PubMed for articles on a similar topic, and look at the terms that were assigned to that article.

3.4.3 Copyright

Most authors, even those who have previously published, know little about copyright. This is where the informationist can assist in breaking down the key points in an intimidating area.

A copyright agreement defines which rights the author maintains or transfers, to what degree, and under which circumstances. It also defines what other people can and cannot do with their work.

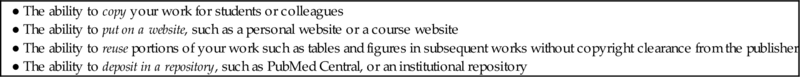

Transferring copyright does not have to be all or nothing. Remind the researcher to read the full copyright agreement carefully. Table 3.4 describes the minimum rights that an author should try to retain.

Table 3.4

Depending on a researcher's funding sources (was the research supported by grant funding? and from which funding body?), there may be mandatory open access requirements. If the copyright transfer agreement does not include terms that are acceptable (e.g., the agreement does not allow self-archiving) the researcher can attach an addendum to the agreement. The publisher may or may not accept this addendum, and if not, they must decide if they still want to publish in this journal.

The SPARC Author Addendum is a legal instrument that modifies the publisher’s agreement and allows authors to keep key rights to their articles. The Author Addendum is a free resource developed by SPARC in partnership with Creative Commons and Science Commons, established nonprofit organizations that offer a range of copyright options for many different creative endeavors (SPARC, 2016).

3.4.4 Open researcher and contributor ID (ORCID)

Informationists can also introduce researchers to the ORCID initiative. The ORCID ID is a URI with a 16-digit number that is unique and persistent for each researcher (ORCID, 2017). Many publishers require authors to have an ORCID ID for publication. Registration is fast and free. Profiles can be populated manually by the researcher, or through article databases/citation linking services and journal publishers. Having an ORCID ID helps address the problem of misattribution due to the shared or ambiguous author names, and the ID remains the same throughout a researcher's career, regardless of change in affiliation (Akers, Sarkozy, Wu, & Slyman, 2016).

3.5 Case study: Republishing

One early morning a discouraged psychiatrist, in a last ditch effort, visited the library asking to speak to a librarian. He explained that he and his colleague had submitted a literature review to a journal and the reviewers determined extensive edits would be required if the manuscript was to be accepted for publication. The authors were required to make these substantive edits within 2 weeks. A consultation was immediately arranged with a Scholarly Communications Informationist. The lead author shared the reviewer’s ratings and comments and met with the informationist to discuss the next steps. The reviewer’s major criticisms were that the methods were inadequate in describing the literature review and the results were not clearly presented and lacking references.

During the first consultation, the informationist also learned that

- ● a bibliographic management tool had not been used

- ● the search terms and databases were recorded but not reported

- ● the citations and in-text formatting did not conform to the instruction to authors

- ● the authors had not considered backup journals to publish their work

- ● the authors had not took full advantage of submitting keywords to describe their paper—submitting just four when the journal allowed up to ten

- ● the authors did not know where the journal was indexed

In this particular case, the client was very motivated to get a publication. As a result, the author shared the submitted manuscript for the informationist to review. The informationist was able to quickly set up an additional consultation to guide the author on database searching, search strategy documentation, and the use of bibliographic management tools, specifically EndNote. Including the databases selected and the search strategies greatly improved the clarity of the research methods. In addition, the authors added a table describing all the studies that were relevant to their overall findings. The expanded search, which included controlled vocabulary and text words, increased the number of citations included in the literature review. By using EndNote the authors were able to quickly import database results and ensure their citations and in-text formatting correctly conformed to the journal's specifications.

To ensure discoverability of the paper, the informationist tracked where the journal was indexed and supplemented the authors’ list of keywords with controlled vocabulary from select indexing databases. The databases chosen were those that the authors routinely searched themselves and that their targeted audience most likely to use.

Using the manuscript's bibliography, PubsHub, JANE, Journal Citation Reports and Ulrich’s Web, the informationist provided a report of three backup journals for manuscript submission. The report included journal descriptions and scope, impact factor, indexing information, acceptance rate and time to publication, and links to instructions for authors.

The author’s resubmitted manuscript was accepted and additional training sessions were offered to the psychiatry faculty. Sessions included EndNote, preparing to publish and database searching.