3. Using knowledge for a better future

This chapter envisages radical changes in our approach to AIDS programs and policies. Achievements will need to be measured with a longer-term perspective, focusing on outcomes rather than process. Uncomfortable topics that have long been avoided will need to be opened up and discussed frankly. These include the long-term future of AIDS treatment, or the equivocal evidence base of some of the programmatic strategies that the AIDS community has pursued. And all stakeholders will need to be more honest and critical when life-saving services are withheld from marginalized communities that need them the most, whether due to funding problems or through apathy, discomfort, or malice.

Much has been achieved in the planning and implementation of sound AIDS programs. As of mid-2010, an estimated 5 million people in low- and middle-income countries were receiving antiretroviral therapy, a 12-fold increase over numbers in 2002. Globally, the annual number of new infections has modestly declined.

Yet it is fair to ask whether the global AIDS effort has always achieved good value for its money. Despite a more than 53-fold increase in AIDS funding in barely over a decade, the epidemic continues to outpace the rate at which programs are delivering.

A review of spending patterns in sub-Saharan Africa suggests that knowledge is often poorly used to guide AIDS efforts (see Figure 3.1). For example, Botswana, Lesotho, and Swaziland are located in the same subregion and have comparable HIV prevalence, yet they devote markedly different shares of total AIDS spending to prevention, treatment, and orphan support programs. Rwanda, Congo, and Côte d’Ivoire have similar HIV prevalence, but administrative costs consume nearly four times as much in Rwanda and Congo. Settings undoubtedly matter, and there are legitimate reasons for divergent national approaches to AIDS. But the sharp differences in resource allocations among similarly situated countries also suggest a lack of strategic rigor.

Figure 3.1. Allocation of HIV/AIDS resources in sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic, UNAIDS 2008.

These failures are especially noteworthy with respect to HIV prevention. Although substantial evidence supports the need for strategies to prevent HIV, national strategies often ignore the evidence or use it poorly. Evidence on whether prevention programs are having any impact is typically lacking, and monitoring efforts generally focus more on counting the number of people who receive services than on measuring actual outcomes.

Prevention efforts also illustrate an additional impediment to success. Even when programs have been rationally planned, sound policies do not often accompany them. One out of three countries lacks a law barring HIV-based discrimination, dozens of countries have enacted punitive laws targeting people living with HIV, and the overwhelming majority of countries have laws in place that reinforce the marginalization of populations most at risk. Many national policies and programs leave HIV stigma largely unaddressed, and few countries in sub-Saharan Africa have implemented comprehensive policy frameworks to promote gender equity and empower women and girls.

This chapter proposes new ways of planning, implementing, and evaluating AIDS programs and policies. It proposes a much closer link between knowledge generation and actual programs and policies. It also argues for a shift in paradigms to generate a steady transition of programmatic authority from international agencies to countries and communities, with plans in place to build the local capacity that will be required to respond to AIDS over the long term.

Designing more effective programs to prevent HIV transmission

If the picture of AIDS is to be substantially more favorable in 2031 than it is today, markedly greater progress is required in preventing new infections. Given the rate at which the pandemic itself is outpacing programmatic scale-up, incremental improvements will not suffice. Prevention programs will need to have radically greater impact in the coming years if a sense of achievement, rather than despair, is to mark the 50th anniversary of the first report of AIDS.

Ensuring success over the next generation demands immediate steps to reverse the historic underinvestment in HIV prevention. Current spending on HIV prevention is highly inadequate to provide prevention services to those who need them.1 In addition, new approaches to the design and delivery of prevention programs are needed to maximize the impact of available tools.

Focusing prevention programs where they are most needed

A first order of business in expanding and improving HIV prevention is to focus programs where they are most needed, using locally specific knowledge to determine prevention strategies, priorities, and resource allocations. National governments will continue to have a key role in allocating resources for HIV prevention, but district and local levels need to assume more authority in planning and setting priorities, to ensure the local relevance of prevention strategies. Recent estimates of HIV incidence by modes of transmission in different countries have demonstrated that national prevention priorities often bear little resemblance to the actual cutting edge of the epidemics. For example, in Swaziland, where people over 25 years of age account for two out of three new infections, few prevention programs focus on older adults.2 Uganda’s prevention strategies are heavily weighted toward young people, yet high rates of new infection among adults in monogamous and steady partnerships represent 43% of new infections.3

Recent analyses have particularly noted the tendency for decision-makers to focus insufficient effort on key populations at elevated risk, especially men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, and sex workers and their clients. Even though men who have sex with men account for 15% or more of incident infections in Kenya and parts of West Africa, prevention programs for this population are virtually nonexistent in such settings.4

The recommendation to use epidemiological and sociological data to determine prevention priorities is not meant to suggest that there is a magic formula for allocating finite resources. In particular, a low percentage of new infections in a particular population may indicate that existing prevention strategies are working, not that the population has no need for services. Indeed, a perfect recipe for a resurgence of AIDS in a vulnerable population is the premature withdrawal of prevention services. As with treatment, prevention of infection is a lifelong undertaking that requires reinforcement and adaptation over time.

Finding synergies in HIV prevention

A number of factors influence HIV transmission: individual norms and desires, physical environments that encourage or impede risk, the dynamics of sexual coupling, access to prevention tools and services, prevailing social norms regarding human sexuality or drug use, gender norms and other broad societal beliefs, and policy frameworks. Effective disease prevention must not only address the individual, but also focus on the social ecology in which individual decisions are made.

Virtually every major public health success has been built on a combination of behavioral, biomedical, social, and structural approaches. As just one example, consider efforts to reduce the harmful effects of tobacco use. These have included individual smoking cessation interventions; biomedical tools to alleviate nicotine dependence; marketing strategies to forge social norms that discourage smoking; and a broad range of policy reforms, including smoking bans in public places, litigation against tobacco companies, and punitive taxation schemes for tobacco products.

A comprehensive sustainable approach to HIV prevention must combine behavioral strategies that promote risk reduction, biomedical strategies that reduce the biological likelihood that risky behavior will result in HIV transmission, and social and structural interventions that address the environmental factors that either impede or support risk reduction.

HIV prevention efforts to date have been overwhelmingly oriented toward a narrow spectrum of individual behavioral interventions, complemented by a handful of biomedical tools (such as antiretrovirals to prevent mother-to-child transmission and adult male circumcision) and minimal support for broad-based social or structural approaches. If one reviews most national HIV prevention plans or grant proposals to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, prevention efforts are typically described as a disconnected set of strategies.10 Frequently, no overarching goals for reducing new infections or changing behaviors are articulated, and potential synergies between prevention and treatment programs are not well examined, at a time when, for example, evidence is growing that antiretroviral therapy can play an important role in reducing HIV transmission.

This haphazard approach to program planning and design for HIV prevention contrasts sharply with the approach taken for treatment programs. In the case of treatment, the vast majority of countries have established clear national targets for treatment scale-up. Systemic barriers to treatment expansion (such as weak procurement and supply management, or poorly developed regulatory systems) have been identified, mapped, and addressed. Rigorous monitoring and evaluation systems have been put in place, and strategic efforts have been implemented to overcome capacity constraints on treatment scale-up. From national policymakers to clinicians, to community leaders, intensive efforts have focused on ways to increase knowledge of HIV status, bring patients into health systems, and help individuals adhere to treatment. Where major gaps have been noted, such as the lack of robust pharmacovigilance systems or inadequate capacity to monitor the emergence of drug resistance, international players have worked with countries to put new systems in place to fill these gaps.

Of course, important differences exist between HIV prevention and treatment. Yet the chasm between our approach to treatment and our efforts to develop, implement, and monitor prevention programs and policies is wide, indeed.

Any sound prevention plan must combine diverse programmatic elements based on documented needs, define how success will be achieved, and articulate a robust approach to monitoring and evaluation to see whether the program is achieving its desired impact. This approach is not a new idea, yet it is striking how seldom this common-sense approach has been put into practice.

To improve the effectiveness and sustainability of AIDS efforts, program planners need to pay greater attention to potential synergies between different components of “combination prevention”. For example, although HIV testing and behavior change programs undoubtedly have a role to play in prevention efforts, they may have greater impact if they are combined and focused on particular populations. For example, consider serodiscordant couples, in which the uninfected partner stands a roughly 80% chance of becoming infected within a year if the infected partner is not treated.11 In Kenya, an estimated 44% of married or cohabitating people living with HIV have partners who are uninfected.12 HIV testing has not always had the desired prevention impact in every setting or for every population, yet overwhelming evidence points to the fact that testing couples together dramatically lowers the odds that the uninfected partner will contract HIV.13 Focusing testing efforts on couples represents precisely the kind of high-impact strategy that long-term success on AIDS requires.

Other synergies are also apparent but often imperfectly captured. Harm-reduction programs for drug users, for instance, will be more effective if they are combined with policy changes or with outreach to reduce official harassment of program participants and service providers.

A redesigned response needs a longer-term horizon. For example, trial results demonstrating that adult male circumcision sharply reduces the risk of female-to-male sexual transmission have prompted countries with high HIV prevalence and infrequent rates of circumcision to begin designing programs to deliver safe circumcision services to adult males. By 2009, 13 countries in sub-Saharan Africa had developed or were in the process of developing operational plans to offer circumcision services to men. This is a healthy development, but a long-term planning perspective would supplement this adult-focused approach with planning and implementation of routine circumcision of male neonates. The reasons for a broader approach to circumcision scale-up are apparent if one thinks about the long term. In 2031, a male child born the year of this book’s publication will be 21 years old. If current patterns of sexual behavior continue, the majority of this year’s male infants will likely be sexually active, and a considerable percentage will already be infected with HIV. By planning now to minimize the epidemic’s long-term burdens, programs will achieve a greater, more sustained effect.

Addressing key social forces and structural factors

To address the long-wave phenomenon of HIV, greater efforts must focus on alleviating the social, political, economic, and environmental factors that increase vulnerability to infection.20 Greater attention to social and structural factors acknowledges the reality that human behavior typically involves an interplay among individual factors (such as knowledge, motivation, skills, and opportunity), environmental factors (such as geographical settings or physical conditions that either promote or inhibit risk reduction), social factors (such as social norms, gender relations, and social capital), and structural factors (such as laws, policies, and economic or institutional arrangements that affect individual decision-making or access to prevention services).

Planning for social and structural components of combination prevention should be driven by the locally specific sociological assessments discussed in Chapter 2. “Generating knowledge for the future.” Based on the articulated causal pathways in particular settings and evidence collected to test social science hypotheses, decision-makers will be better equipped to move from a short-term, emergency-style response to one that is more sustainable and enduring. For example, depending on documented needs and national circumstances, a comprehensive strategy to prevent transmission during sex work combines typical short-term approaches (for example, condom distribution, community mobilization, and increased health service access) with longer-term strategies, such as legal reform, efforts to alter gender norms, creation of employment alternatives to sex work, and efforts to deter sex tourism.

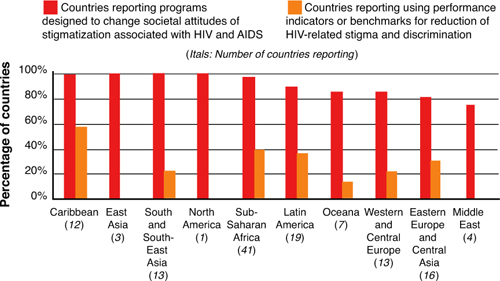

Anti-stigma programming offers another example of how a strategically designed program of combination prevention might differ from current approaches. Stigma is almost universally cited as a major impediment to service scale-up and utilization, and most countries include anti-stigma language in their national AIDS plans. But national plans seldom articulate the specific elements and desired intermediate and ultimate outcomes of anti-stigma strategies, and often do not specifically budget for stigma programming. As Figure 3.2 describes, anti-stigma efforts are seldom monitored against specific performance indicators. Moreover, many countries undermine the success of even haphazardly assembled antistigma efforts through policy frameworks that often reinforce and perpetuate stigma. As recommended by the aids2031 Programmatic Response Working Group, every country should have specific budgets, work plans, and performance targets, to implement strategies to alleviate stigma and prevent discrimination.

Figure 3.2. Percentage of countries (by region) reporting programs designed to change societal attitudes of stigmatization associated with HIV with and without impact indicators.

Adapted from UNAIDS Country Progress Reports 2008.

To develop, implement, and monitor strategies to address social and structural drivers, decision-makers should undertake an evidence-guided, multistep process. To take the example of addressing a concentrated epidemic characterized by substantial HIV transmission among sex workers, decision-makers should consider the following:

- Identify the target populations and locations for the intervention.

- Identify the key behavioural patterns and drivers of behavioural patterns for the target population (for example, nature of sex work, primary motivations for becoming involved in sex work, applicable legal frameworks, crucial power-brokers, role of law enforcement).

- Choose the level of structural intervention (for example, legal reform, community empowerment, interventions to reduce police violence, and so on).

- Describe planned or potential changes and outcomes as a result of the structural intervention (for instance, increase in condom use, formation of sex worker networks, reductions in reported violence against sex workers, changes in police attitudes).

- Design the intervention (for example, enhanced opportunities for self-help among sex worker networks, condom access and promotion, anti-violence programs, mechanisms for legal recourse, advocacy for decriminalization, income-generating alternatives, and so on).

- Implement, monitor, evaluate, and feed results into program design and implementation.

This approach is potentially useful in addressing epidemic drivers in broadly diverse settings. For example, where locally specific analyses suggest that gender inequality is increasing the vulnerability of women and girls, program planners may reasonably conclude that strategies to promote gender equality and empower women represent essential components of a comprehensive prevention response. Depending on available data, such approaches could include microfinance initiatives, legal recognition of property and inheritance rights, and other programs to increase women’s earning potential and economic independence; legal reform to outlaw violence against women; and social change processes to alter gender norms, with a particular focus on changing the attitudes and behavior of men and boys.

More focused policy reforms may also contribute to risk reduction or improve the effectiveness of prevention efforts. For example, Thailand, Cambodia, and other countries have used regulatory powers to increase condom use in brothels, leading to dramatic reductions in HIV transmission. Similarly, changing laws to allow pharmacies to sell syringes has been shown to reduce needle sharing and the prevalence of used syringes in public places.21 Analyses also suggest that implementing supervised injection facilities for drug users is a cost-effective strategy to reduce the sharing of needles and to link people who use drugs into service systems.22

As with other components of combination HIV prevention, social or structural interventions need to be carefully planned and strategically incorporated as elements of a comprehensive approach to AIDS. Informed by a rigorous analysis of relevant social dynamics, processes, and contexts, structural approaches should be articulated with clear causal pathways, incorporating specific, well-designed indicators for monitoring progress. Above all, social and structural interventions cannot be viewed as a short-term fix in the way that behavioral interventions have often erroneously been regarded. Structural approaches need to be linked to budget lines that are sufficient to support project cycles of 5 to 15 years or more.

Sustaining HIV/AIDS treatment

The AIDS field has drawn inspiration and a sense of accomplishment from the steadily rising rates of treatment coverage in recent years. These achievements are real, but they also mask a more disturbing reality. With at least two million people dying of AIDS-related causes each year, the reality is that coverage levels are artificially inflated by our failure to deliver life-prolonging treatments to those who need them. The continuing high death toll—most of it preventable—effectively reduces the treatment denominator, partially obscuring the degree to which the goal of universal access to treatment remains unfulfilled.

We can and must do better. It will not be possible to achieve ambitious aims for significantly reducing the prevalence of HIV by 2031 without ensuring treatment to those who need it. Despite the considerable progress that has been made in scaling up treatment programs, most people who need antiretroviral therapy currently lack access.23 Although the scale-up of treatment programs has arguably been guided somewhat more by evidence than corresponding efforts to prevent new infections, important challenges that threaten the long-term viability of treatment efforts remain. In particular, changes in program design and delivery strategies are needed to maximize the efficiency and sustainability of HIV treatment. A new initiative to maximize the use of antiretroviral therapy, called “Treatment 2.0,” advocates for “better combination of treatment regimens, cheaper and simpler diagnostic tools, and community-led approaches to delivery.”24

Minimizing treatment costs

Many countries are missing opportunities to lower the costs of commodities used for treatment, even in an era when generic competition, agreements with pharmaceutical companies, and the support of such organizations as UNITAID and the Clinton Foundation are helping reduce the costs of drugs and diagnostics. According to one aids2031 analysis, there is considerable variation across countries in the prices paid for the same antiretroviral drugs, even among countries of a similar socioeconomic status.25

To maximize the long-term impact of finite funding, it is essential that national decision-makers, program implementers, and international donors collaborate to make sure that procurement of medicines and other health commodities is as efficient as possible. WHO’s AIDS Medicines and Diagnostic Service provides up-to-date guidance on the most recent purchase prices for antiretrovirals and other technologies, but it is evident that many stakeholders are not availing themselves of this resource. Incentives should be built into AIDS financing schemes to ensure that purchases reflect the best value for money (an issue that Chapter 4, “Financing AIDS programs over the next generation,” addresses in greater detail).

Additional work is also needed by organizations such as the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), formerly called the Clinton Global HIV/AIDS Initiative, to further reduce the costs of producing key commodities. Mechanisms to lower commodity costs include technology transfer, facilitated negotiations between different players in the production chain, volume guarantees, pooled purchasing, and even support for minority producers to guarantee competition.

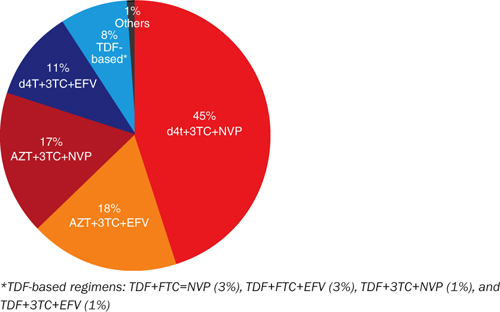

Maximizing treatment gains: a new approach to HIV treatment

In 2008, all but 2% of patients on antiretroviral therapy in low- and middle-income countries were receiving first-line regimens.26 However, the growth over time in demand for second-line regimens is inevitable, as drug resistance develops. While the prices of second-line regimens have fallen somewhat in recent years, they remain several times more costly than first-line regimens.27 Sustaining HIV treatment access requires concerted global efforts to maximize the time patients are able to sustain first-line regimens and to lower the prices of the second-line regimens that will be required in future years.

Clear evidence does not exist regarding which affordable regimen will last the longest and thereby preserve treatment gains. As Figure 3.3 illustrates, developing countries have opted for a wide range of first-line regimens. These patterns strongly suggest that many countries are placing patients on suboptimal regimens that invite emergence of resistance, increased patient drop-out due to toxicities, and expedited the need for more costly second- and third-line regimens.

Figure 3.3. Main first-line antiretroviral regimens used among 2.4 million adults in 36 low- and middle-income countries (December 2008).

Source: WHO Towards universal access report 2009.

This is a critical research priority to enable program planners in low-income countries to use limited resources to maximize individual health and longevity.

Especially in low-income countries where large proportions of the population lack access to the most rudimentary health services, existing second-line regimens likely will remain unaffordable. With competing health priorities, some health systems may decide that it is impossible to deliver second-line regimens through the public sector. Although it is the conclusion of aids2031 that sufficient resources exist to ensure access to high-quality HIV prevention and treatment services over the next generation (a proposition more fully explained in Chapter 4), prioritizing among competing health needs is the job of national governments and country-level stakeholders, not technical experts at the global level.

Regardless of a country’s decision regarding access to second- and third-line drugs, it is evident that selecting the longest-lasting first-line regimen is an urgent necessity. Not only will optimally effective first-line regimens delay or avert the much higher costs associated with second-line drugs, but in settings in which second-line therapy is not available, they will help keep patients alive and healthy until future research breakthroughs can deliver additional, more affordable options for resource-limited settings.

Enhancing treatment adherence

To date, treatment scale-up has been based almost exclusively on a traditional medical model. Clinicians aim to prescribe effective regimens and apply the best diagnostic tools at their disposal. From a programmatic standpoint, monitoring has focused primarily on the number of individuals receiving antiretroviral treatment.

Although all these factors are critically important, they are insufficient on their own to maximize and sustain medical outcomes. HIV treatment demands especially high levels of treatment adherence, with suboptimal adherence representing the primary cause of treatment failure. With future access to second-line regimens uncertain in many of the countries most heavily affected by the pandemic, maximizing treatment adherence is vital to long-term sustainability of treatment gains.

Several case studies have identified patient support strategies that appear to increase treatment adherence, such as treatment “buddies” who work with patients to address impediments to adherence.28 However, these initiatives are infrequently incorporated in clinical settings. Some studies have found antiretroviral adherence rates in developing countries to be equal to or superior to those documented in high-income settings,29 while other field-based studies have detected significantly less favorable adherence levels.30

Funders and program implementers urgently need to prioritize adherence support services as essential components of HIV treatment programs. These services are vital to optimizing treatment gains over the long term.

An enabling environment for a sound programmatic response

For a disease so closely linked to social context, with burdens disproportionately visited on key marginalized populations, the importance of a sound and supportive legal framework is evident. Unfortunately, problematic legal frameworks continue to undermine rights-based approaches to AIDS and deter individuals most at risk from using needed services. This problem is not new, but has instead been a fundamental weakness of AIDS efforts from the epidemic’s beginning. As we look toward the next generation and the challenge of sustaining an optimally effective AIDS response, significantly stronger global solidarity and greater political courage are needed to remove legal and policy barriers.

Institutionalized discrimination reinforces the social marginalization of the groups at highest risk of infection. Despite the strategic imperative of delivering evidence-informed prevention services to these vulnerable groups who are being devastated by the epidemic, countries too often erect immense barriers to sound, rights-based programming. Among 92 countries reporting data to WHO and its partners in 2009, only 30 countries permitted needle and syringe exchange programs, and opioid substitution therapy was available in only 26 countries.31 As Figure 3.4 illustrates, such barriers are especially common in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where AIDS epidemics have historically been driven by drug-related transmission. More than 50 countries impose coercive or compulsory treatment or the death penalty for people convicted of drug offenses,32 a legal approach that inevitably drives drug users away from services. Seventy-six countries (most of them low- and middle-income countries) criminalize sexual relations between members of the same sex, including seven that provide for the death penalty.33 And laws in at least 110 countries make it illegal to offer or solicit sex in exchange for money.34

Figure 3.4. Percentage of countries reporting laws, regulations, or policies that present obstacles to services for injecting drug users.

Source: UNAIDS Country Progress Reports 2008.

A prerequisite to a sound AIDS response is for all countries to have in place a minimum legal framework to remove key legal and policy impediments. As recommended by the aids2031 Social Drivers Working Group,35 this minimum legal standard includes the following:

• Decriminalize HIV status, transmission and exposure

• Decriminalize same-sex relationships/sexual practices

• Guarantee equal rights of people living with HIV

• Guarantee equal rights to men and women

• Eliminate laws that limit access to health services for marginalized populations, including sex workers, people in same-sex relationships, and drug users

• Decriminalize harm-reduction approaches for prevention of AIDS among those injecting drugs

If widespread enactment of this minimum framework is to come about, political decision-makers cannot be let off the hook for actions that undermine AIDS efforts. Global solidarity can, in fact, make a difference. In recent years, substantially greater attention has focused on the corrosive and discriminatory effects of national policies that restrict the ability of people living with HIV to cross national borders. Although such laws have been a feature of national AIDS policies since the pandemic’s first decade, there are signs that this discriminatory edifice is beginning to crumble in the face of global criticism. Over the last two years, countries such as the Czech Republic, South Korea, and the U.S. have taken steps to remove such counterproductive policies.

Building sustainable national and local capacity

Even while urging national ownership of the AIDS fight, the international community has largely sought to implement programs for developing countries. With a certainty that they know best how to respond to culturally distinct epidemics in countries they only partially understand, international donors and technical agencies have imposed theory-based approaches that inevitably obtain disappointing results. In the process, the international community has encouraged a dependence on external AIDS assistance in many countries that is wholly incompatible with the stated aim of national ownership.

Not only has this approach yielded unsatisfactory results in many cases, it is also a poor recipe for sustainability. Donors are often fickle when it comes to their commitments, and fashions in the international development field frequently change over time. Basing the long-term AIDS response on such a fragile base is dangerous.

This approach is also indicative of the kind of short-term perspective that has frequently characterized AIDS programs. In an emergency phase, getting programs up and running may indeed be the first priority. Over the long term, however, it will be necessary to have strong, durable, self-replenishing mechanisms in place to support the generations-long struggle against AIDS.

Transitioning to local control

A new approach is urgently needed to build the professional skills, managerial expertise, and analytical aptitude in the countries and communities that will grapple first-hand with AIDS for decades to come. As the aids2031 Programmatic Response Working Group recommends,36 donors, developing country governments, and multilateral agencies should enforce a “new compact” for AIDS programs. Contracts for the delivery of AIDS programs in low- and middle-income countries should include clear, unambiguous milestones for building capacity. Where appropriate, this would include creating physical infrastructure and providing on-the-job training and professional development for in-country staff to acquire the skills and experience they will need to administer the program over the long run. Not only will this approach promote a sustainable response, but it will also be more efficient, as financial requirements for international staff are nearly always greater than for local personnel.

Each contract of an international NGO should include an extensive handover period, governed by specific milestones, during which day-to-day management of the program is steadily transitioned to in-country staff—either to a local community organization or to a public agency. International NGOs must understand that their ability to compete for future contracts from donor agencies will depend on a strong track record of building sustainable capacity in countries. And donors need to commit to a continuation of funding for successful, locally managed programs.

Strengthening national systems

Weak national infrastructure has repeatedly undermined the impact of AIDS programs. Special attention has recently focused on strengthening national health systems, but a durable AIDS effort depends on the capacity of other systems as well, including education, welfare, and justice.

Although strengthening health systems is important, both for AIDS programs and other health priorities, the emerging discourse poses the challenge as an either/or choice between focusing on disease-specific programs and strengthening broader health systems. This type of thinking would have made the historic successes of the AIDS response impossible to achieve. The AIDS response has actually been one of the drivers of the increases in Official Development Assistance (ODA) for health during the last decade. Sufficient funds exist to provide robust support for both scaled-up efforts to address priority diseases and actions to strengthen national health systems, as Chapter 4 discusses in greater detail. Careful planning is needed to ensure that the broader systemic benefits of AIDS funding are maximized.

To the extent that the world is serious about strengthening health systems, it will demonstrate seriousness in monitoring and evaluating such initiatives. Initiatives for strengthening health systems should have clearly defined, transparent impact indicators in place, with regular reporting of results.

Building AIDS-resilient communities

If AIDS has taught us one lesson, it is that communities, neighborhoods, and social networks have an enormous capacity to influence attitudes, drive change and innovation, and persuade decision-makers to pay attention to their needs. Indeed, one cannot understand AIDS without recognizing the potential for even the most marginalized and disempowered groups to create change. Building strong and enduring social capital in affected communities enables a robust community response to continually regenerate itself, a recipe for a more sustainable response.

Placing communities at the center of AIDS programs has important implications for programmatic effectiveness and sustainability. Programmatic efforts must be built on a strong community foundation to succeed over the long run.

Different types of social capital are important to a long-term AIDS strategy. Bonding social capital is the sociological term for the horizontal relationships between members of the same group that reinforce social solidarity. Bridging social capital refers to social interactions between different groups. Linking social capital connects groups of people across power hierarchies, connecting a less powerful social group with individuals or institutions that possess greater power and influence.

Bonding social capital is the glue that holds communities together. The power of group solidarity has helped make some of the most noteworthy community-centered HIV-prevention efforts so successful. Although it is most common to think of bonding social capital as a phenomenon that occurs within a geographic setting, the enormous expansion of international travel and communication has also given rise to emerging global “communities” centered on more shared characteristics than a common geographic setting. In contrast to the internal community dynamics that characterize bonding social capital, bridging social capital is defined by the external links that communities establish with other groups, potentially increasing the reach of community-generated strategies.

Linking social capital is the means by which a disempowered or disadvantaged group calls attention to its needs and persuades those with power to take action to benefit the community. Linkages between relatively disempowered communities and empowered actors with the ability to make or influence decision-making on public policy have played an important role in strengthening AIDS efforts.37 The Treatment Action Campaign’s successful drive to persuade the South African government to alter its misguided earlier approach to AIDS is an excellent example; although street protests, creative use of the media, and other political tools played a central role in bringing policy change, mobilizing partnership with diverse and influential actors was also key.38

Unfortunately, many trends in AIDS programming undermine the social capital on which a sustainable and vigorous response depends. Consider bonding social capital, for instance. The ideal end result of bonding social capital is the development of AIDS-resilient communities that collaborate to identify problems, agree on goals and priorities, and implement responses to address problems.39 Characteristics of AIDS-resilient communities include open community dialogue, collaborative decision-making, and reliance on the community’s strengths and resources to respond to problems.40

Unfortunately, key attributes of AIDS programming often weaken the social capital needed to produce AIDS-resilient communities. Community members may serve as key informants during a program’s formative stage or sit on a program’s consumer advisory board, for example, but far too often AIDS programs fail to encourage true community ownership or leadership.

A separate set of problems impedes linking social capital. Often disparities in power are so vast that success stories such as the Treatment Access Campaign are unlikely ever to emerge without focused action. Yet given the documented power of community activism in the history of AIDS, it is remarkable how little funding is made available for civil society advocacy and watchdog functions.

Investing in medical education

New cadres of AIDS-competent health professionals are needed to meet the long-term challenge AIDS poses in developing countries. Home to two-thirds of people living with HIV,41 Southern Africa claims only 3% of the global health workforce.42 Although task shifting, professional mentoring programs, and telemedicine techniques certainly help extend available human resources further than they would otherwise go, they cannot compensate over the next generation for an acute shortage of health workers needed to deliver essential treatment and care.

The prevailing scattershot approach to building durable human resources for health needs to be replaced by a much more ambitious, more strategic, adequately funded, decades-long initiative to build regional and national institutions capable of serving as a human resource pipeline for health systems. The well-documented “brain drain” of health personnel from poor countries to high-income countries has sometimes deterred donors from prioritizing investment in medical and public health education systems in low- and middle-income countries. This needs to change. Sustaining an effective AIDS response is simply not feasible without deploying substantial numbers of new health personnel in high-burden countries.

Managing programs to enhance their long-term efficiency and effectiveness

In the transition from a singular emphasis on programmatic scale-up at any cost to an approach that focuses as much effort on maximizing quality, efficiency, and impact, programs need to be managed more rigorously for results.43 This requires not only a new mentality among national governments, international donors, and program implementers, but also new skills in implementing organizations and access to user-friendly monitoring and management tools.

Recent experience has demonstrated the potential benefits of using business principles to guide programmatic scale-up. Created in 2002, the Avahan India AIDS Initiative, a joint collaboration between the Indian government and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, undertook investigations and mapping to understand the target populations, conducted marketing research to determine their needs and preferences, established specific programmatic goals and benchmarks for program delivery and management, and implemented rigorous monitoring systems to determine whether such targets had been achieved.44 These management practices and monitoring tools generated a high degree of confidence that Avahan had achieved the coverage levels it sought.

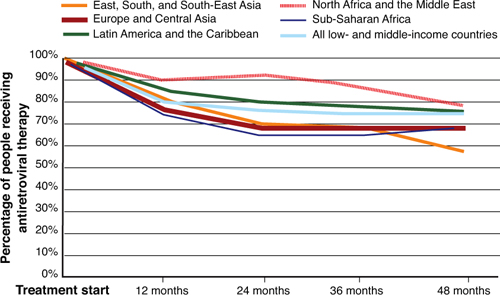

Prevention programs are not alone in the need to use business practices to guide programming and monitoring efforts. Treatment programs with high drop-out rates would also benefit from better monitoring systems. As Figure 3.5 illustrates, retention rates may be cause for concern; in Asia, for example, fewer than 60% of antiretroviral patients were still enrolled in treatment 48 months after starting therapy.

Figure 3.5. Trends in retention on antiretroviral therapy in low- and middle-income countries by regions (2008).

Source: WHO Toward universal access report 2009.

Patients may drop out of a treatment program for numerous possible reasons. A number of developing countries are using electronic medical record systems to better monitor and interpret data on patient retention, recognizing that such systems would more than pay for themselves by improving care coordination and preserving treatment gains.

Ensuring quality

In a sustainable, long-term AIDS response, a commitment to scaling up must be matched by a commensurate dedication to the highest service quality. If a sex worker who seeks HIV counseling encounters social disapproval and hostility, for instance, the counseling program will not achieve its desired ends because the client is unlikely to continue seeking services at the site. As a recent analysis commissioned by UNAIDS advises, improving the quality of HIV-prevention programming involves a continuous loop of inspection, quality assurance, continuous quality improvement, and total quality management.45 In short, quality control should continually inform service delivery and adaptation of programmatic efforts.

Promoting the efficient use of finite resources

The paucity of data on AIDS service efficiency is striking, and the limited available evidence suggests that there is need for improvement. In a five-country study, the cost per client receiving HIV voluntary counseling and testing varied from US$3 to US$1,000, independent of the size of the program.46

A more rigorous approach to program management is required to increase efficiency. Mapping average unit costs for providers in a single country, it is possible to clearly differentiate the most efficient providers from the most inefficient.47 Increased investment in operational research and more systematized service monitoring could lead to the establishment of baseline and target unit costs to guide program oversight.

Unfortunately, current ways of doing business are not always conducive to an efficient use of limited resources. For example, national governments and individual program managers are burdened with multiple, inconsistent donor-reporting requirements. In a typical low- or middle-income country that relies on international donor funding, multiple channels of aid from multiple sources require country officials to submit thousands of quarterly reports each year and host hundreds of site visits.48 Instead of focusing on service delivery, country officials and program managers are drowning in paperwork. International donors have repeatedly pledged to streamline, harmonize, and align reporting requirements to support rather than undermine national strategies, including in the Paris Declaration on AIDS Effectiveness and in the broadly endorsed “Three Ones” approach to HIV programming. The “Three Ones” approach calls for 1) a single agreed-upon national AIDS framework that includes the work of all partners; 2) a single national AIDS coordinating body; and 3) a unified monitoring and evaluation system. Similar to repeated donor pledges to devote at least 0.7% of national wealth to international development assistance, the commitment to lessen reporting burdens and improve coordination in support of national plans has been honored only infrequently.49 Taxpayers have every right to know that their country’s spending on AIDS is being used for its intended purposes. However, the go-it-alone approach of individual donors with respect to reporting requirements reduces efficiency and diminishes the impact of AIDS spending. It also fails to promote accountability for results because few donor-reporting schemes collect information on the impact of their programs.

Placing people living with HIV at the center of AIDS efforts

In the quest to sustain AIDS programs for the coming decades, it is obvious that no group in the world has a clearer stake in a sustainable response than people living with HIV. They are also ideally positioned to lead AIDS programmatic efforts and deliver essential services and support. Not only are people living with HIV uniquely qualified to provide information and support to their peers, but their encounters with service recipients are more likely to be informed by an intimate and nuanced understanding of the challenges these individuals face.

The absence of people living with HIV in programmatic efforts is especially acute in the prevention field. This is a curious shortcoming, in that individuals who are living with HIV often have an especially extensive understanding of the factors and circumstances that contribute to risky behavior and of the impediments that people face in avoiding transmission. For those who are uninfected, people living with HIV can also be the most compelling source of information and support for risk reduction.

AIDS programs, especially prevention programs, should undertake the massive hiring of people living with HIV. In addition to strengthening the relevance and cultural competence of AIDS services, this approach would help develop new cadres of AIDS leaders, support efforts to alleviate AIDS stigma, and provide economic opportunities for many people who currently lack them.

Cultivating a new generation of AIDS leaders

To ensure that AIDS programs have the well-prepared leaders they need to thrive in future decades, focused efforts should be undertaken to cultivate, develop, and train a new generation of AIDS leaders. In 2009, aids2031 convened the second of two global Young Leaders Summits, where young people recommended steps to actively promote vibrant youth leadership in AIDS programming. The young people at the summit endorsed a “5% for the Future Campaign,” calling for at least 5% of donor contributions to be allocated to youth-led organizations as a strategy to build sustainable AIDS leadership and encourage more youth-relevant AIDS programs. They also recommended the establishment of a Young Leadership Mentorship Hub to enable young leaders to exchange ideas with, and learn from, more established leaders, including decision-makers in the media and in the AIDS policy field.

Political leadership for an effective response

This chapter has focused on translating knowledge into practice. With better knowledge, the aids2031 Consortium contends, it will be possible to achieve substantially more favorable results.

Too often lack of knowledge is not the only obstacle to a successful AIDS response. Instead, it is the timidity of political leaders, who have refused to put in place policies and strategies known to be effective. Time after time, political leaders have heeded popular opinion more than the evidence of what works.

Not only do political courage and commitment need to increase in the coming years if the AIDS challenge is to be met, but a new type of leadership also is required. For the typical political leader—focused on the next election cycle or on time-limited work plans—the strategic horizon seldom extends beyond three or five years. However, mounting a sustainable fight against the generations-long challenge of AIDS requires continuity, long-term planning, and a broad national consensus. Leaders need to summon the resources within themselves to make sound decisions on AIDS, even when results may sometimes be apparent only many years down the road.

Forging a durable national consensus on AIDS requires true leadership. Decision-makers need to avoid the temptation to pit groups against one another or to pretend that AIDS is not a national priority because it often primarily affects marginalized segments of society. Instead, leaders need to lead, working to instill values of social solidarity, inclusion, and compassion throughout society.

Over the next generation, the success or failure of the AIDS response will depend above all else on strong, enduring, evidence-based national leadership. But global solidarity also is critical to mobilizing needed resources and generating critical new knowledge and health tools. Preserving the potential of the AIDS response to inspire passion and goodwill will remain vital in the coming years.

With the looming challenge of climate change and a proliferating array of security issues, the global political agenda continues to expand. However, the pandemic is not going away. AIDS must remain high on the global political agenda—at the United Nations, among donor governments, and in key political groupings, such as the G-20.

In high-prevalence countries, AIDS needs to remain a paramount political issue in the coming decades, involving people from all walks of life in a common national endeavor. Senior political leaders and parliamentarians need to speak openly and often about their national epidemic. An annual parliamentary debate should be mandatory in high-burden countries, informed by a report on country progress, remaining gaps, and future action plans.

Building and maintaining national commitment will be especially challenging in countries with lower HIV prevalence. In these settings, AIDS will not be one of the foremost issues in the minds of political leaders, but it cannot be allowed to slip into oblivion, because this would risk an expansion of the epidemic. Here, regional groupings have a potentially important role to play in building solidarity and commitment for continuing vigilance.

Long-term success demands overcoming political impediments that have long frustrated AIDS efforts. In particular, political courage is required to prioritize sound, rights-based approaches with respect to marginalized populations that have too often been ignored, such as men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, and sex workers. The difficulties in overcoming popular prejudices are real, but the history of AIDS teaches that genuine progress is achievable.

Endnotes

1 Global HIV Prevention Working Group, Global HIV Prevention Progress Report Card, http://www.globalhivprevention.org (Accessed 7 August 2010).

2 Mngadi, S., N. Fraser, H. Mkhatshwa, T. Lapidos, et al., Swaziland: HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis (Mbabane, Swaziland: National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS, 2009).

3 Colvin, M., Gorgens-Albino, M., and Kasedde, S., “Analysis of HIV prevention responses and modes of HIV transmission: the UNAIDS-GAMET–supported synthesis process,” 2008, http://www.unaidsrstesa.org/files/u1/analysis_hiv_prevention_response_and_mot.pdf (Accessed August 1, 2010).

4 Gelmon, L., P. Kenya, F. Oguya, B. Cheluget, and G. Haile, Kenya: HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis (Nairobi, Kenya: National AIDS Control Council, 2009); Bosu, W., K. Yeboah, G. Rangalyan, K. Atuahene, et al., Modes of HIV Transmission in West Africa: Analysis of the Distribution of New HIV Infections in Ghana and Recommendations for Prevention (Accra, Ghana: Ghana AIDS Commission, 2009).

5 UNAIDS, AIDS Info: 2010 UNAIDS Reference Report (Geneva: 2010).

6 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Pregnancy and Childbirth, 2007. Accessed 14 June 2010 at www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/perinatal/index.htm.

7 UNAIDS and WHO. 2009. Op cit.

8 Ibid.

9 Botswana National AIDS Control Agency, Progress Report of the National Response to the 2001 Declaration of Commitment on HIV and AIDS: Botswana Country Report 2010 (2010); Republic of Rwanda, United Nations General Assembly Special Session on HIV and AIDS Country Progress Report: 2008-2009, 2010. Accessed 26 May 2010 at http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/rwanda_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf; Zambia Ministry of Health and National AIDS Council, Zambia Country Report: Monitoring the Declaration of Commitment on HIV and AIDS and the Universal Access (2010).

10 The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Report of the Technical Review Panel and the Secretariat on Round 9 Proposals, 20th Board Meeting, http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/trp/reports (Accessed August 7, 2010).

11 Wawer, M. J., R. H. Grey, N. K. Sweankambo, D. Serwadda, et al., “Rates of HIV-1 Transmission Per Coital Act, by Stage of HIV-1 Infection, in Rakai, Uganda,” Journal of Infectious Disease 191, no. 9 (2005): 1,403–1,409.

12 National AIDS and STI Control Program, Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2007 (Nairobi: Kenya Ministry of Health, 2009). Accessed 23 June 2010 at www.usaid.gov/ke/ke.buproc/AIDS_Indicator_Survey_KEN_2007.pdf.

13 Allen, S., E. Karita, E. Chomba, D. L. Roth, et al., “Promotion of Couples’ Voluntary Counseling and Testing in Individuals and Couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: A Randomized Trial,” BMC Public Health 7 (2007): 349.

14 Des Jarlais, D. C., Perlis, T., Arasteh K, et al. “HIV incidence among injecting drug users in New York City, 1990 to 2002: Use of serologic test algorithm, to assess expansion of HIV prevention services,” Am J Public Health 95 (2005): 1439–1444.

15 WHO, UNICEF, and UNAIDS, Towards Universal Access: Scaling Up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009).

16 Strathdee, S. A., Hallett, T. B., Bobrova, N., et al. “HIV and risk environments for injecting drug users: the past, present and future,” The Lancet 376 (2010): 268–284.

17 Mathers, B. M., L. Degenhardt, A. Hammad, L. Wiessing, et al., “Global Epidemiology of Injecting Drug Use and HIV Among People Who Inject Drugs: A Systematic Review,” The Lancet 372, no. 9,651 (2008): 1,733–1,745.

18 WHO, UNICEF, and UNAIDS. 2009. Op cit.

19 http://www.viennadeclaration.com/the-declaration.html (Accessed on August 5, 2010).

20 Rao Gupta, G., and E. Weiss, “Gender and HIV: Reflecting Back, Moving Forward,” in HIV/AIDS: Global Frontiers in Prevention/Intervention, edited by C. Pope, R. T. White, and R. Malow (New York: Rutledge, 2008).

21 Groseclose, S. L., B. Weinstein, T. S. Jones, L. A. Valleroy, L. J. Fehrs, and W. J. Kassler, “Impact of Increased Legal Access to Needles and Syringes on Practices of Injecting Drug Users and Policy Officers—Connecticut, 1992–1993,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes Human Retroviral 10, no. 1 (1995): 71–72.

22 Des Jarlais, D. C., K. Arasteh, and H. Hagan, “Evaluating Vancouver’s Supervised Injection Facility: Data and Dollars, Symbols and Ethics,” Canadian Medical Association Journal 179 (2008): 1,105–1,106.

23 WHO, UNICEF, and UNAIDS. 2009. Op cit.

24 Is this the Future of Treatment? Imagine Treatment 2.0, UNAIDS OUTLOOK Report 2 (2010): 46–53.

25 Wirtz, V., Forsythe, S., Valencia-Mendoza, A., et al, “Factors influencing global antiretroviral procurement prices,” (2009) (Suppl 1):S6.

26 WHO, UNICEF, and UNAIDS. 2009. Op cit.

27 Ibid.

28 Behforouz, H. L., P. E. Farmer, and J. S. Mukherjee, “From Directly Observed Therapy to Accompagnateurs: Enhancing AIDS Treatment Outcomes in Haiti and in Boston,” Clinical Infectious Diseases 38, no. S5 (2004): S429–S436.

29 Coetzee, D., K. Hildebrand, A. Boulle, G. Maartens, et al., “Outcomes After Two Years of Providing Antiretroviral Treatment in Khayelitsha, South Africa,” AIDS 18, no. 6 (2004): 887–895; Katzenstein, D., M. Laga, and J. P. Moatti, “The Evaluation of the HIV/AIDS Drug Access Initiatives in Cote D’Ivoire, Senegal, and Uganda: How Access to Antiretroviral Treatment Can Become Feasible in Africa,” AIDS 17, no. 3 (2003): S1–S4.

30 Nwauche, C. A., O. Erhabor, O. A. Ejele, and C. I. Akani, “Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among HIV-Infected Subjects in a Resource-Limited Setting in the Niger Delta of Nigeria,” African Journal of Health Sciences 13 (2006): 13–17.

31 WHO, UNICEF, and UNAIDS. 2009. Op cit.

32 International Planned Parenthood Federation, Verdict on a Virus: Public Health, Human Rights, and Criminal Law, 2008. Accessed 23 June 2010 at www.ippf.org/en/What-we-do/AIDS+and+HIV/Verdict+on+a+virus.htm.

33 Ottosson, D., State-Sponsored Homophobia: A World Survey of Laws Prohibiting Same Sex Activity Between Consenting Adults (Brussels: International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association, 2009).

34 International Planned Parenthood Federation, Verdict on a Virus: Public Health, Human Rights, and Criminal Law, 2008. Accessed 23 June 2010 at www.ippf.org/en/What-we-do/AIDS+and+HIV/Verdict+on+a+virus.htm.

35 aids2031 Social Drivers Working Group, Revolutionizing the AIDS Response: Enhancing Individual Resilience and Supporting AIDS Competent Communities (Clark University, Worcester, Mass.: aids2031 Social Drivers Working Group, 2010).

36 Aids2031 Programmatic Working Group Report, “Making Choices, Embracing Complexity, Driving and Managing Change: The HIV Programmatic Response Over the Next Generation,” http://www.aids2031.org/working-groups/programmatic-response (Accessed August 9, 2010).

37 De Waal, A., AIDS and Power: Why There Is No Political Crisis—Yet (London: Zed Books, 2006).

38 Grebe, E., “The Emergence of Effective ‘AIDS Response Coalitions’: A Comparison of Uganda and South Africa,” presentation paper, aids2031 Mobilizing Social Capital in a World with AIDS Workshop, Salzburg, Austria, March 2009.

39 Fisher, W. F. and B. Thomas-Slayter, 2010 Report and Recommendations from the Workshop on Mobilizing Social Capital in a World with AIDS, March 2009 (Salzburg, Austria); Campbell, N., E. Murray, J. Darbyshire, J. Emery, et al., “Designing and Evaluating Complex Interventions to Improve Health Care,” British Medical Journal 334, no. 7,591 (2007): 455–459; Campbell, C., Letting Them Die: Why HIV/AIDS Prevention Programs Fail (Indiana University Press, 2003); Lamboray, J., and S. M. Skevington, “Defining AIDS Competence: A Working Model for Practical Purposes,” Journal of International Development 13, no. 4 (2001): 513–521.

40 Campbell, N., E. Murray, J. Darbyshire, J. Emery, et al., “Designing and Evaluating Complex Interventions to Improve Health Care,” British Medical Journal 334, no. 7,591 (2007): 455–459.

41 UNAIDS and WHO, AIDS Epidemic Update (Geneva: UNAIDS and WHO, 2009).

42 World Health Organization, The Global Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006). Accessed 23 June 2010 at www.who.int/whr/2006/en/.

43 Bertozzi, S. M., M. Laga, S. Bautista-Arredondo, and A. Coutinho, “HIV Prevention 5: Making HIV Prevention Programs Work,” The Lancet 372, no. 9,641: 831–844.

44 Verma, R., A. Shekhar, S. Khobragade, R. Adhikary, B. George, et al., “Scale-Up and Coverage of Avahan: A Large-Scale HIV-Prevention Program Among Female Sex Workers in Four Indian States,” Sexually Transmitted Infections 86 (2010): 176–182.

45 Maguerez, G., and J. Ogden, UNAIDS Discussion Document: Catalyzing Quality Improvements in HIV Prevention: Review of Current Practice, and Presentation of a New Approach (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2009).

46 Marseille E., L. Dandona, N. Marshall, P. Gaist, S. Bautista-Arredondo, et al., “HIV Prevention Costs and Program Scale: Data from the PANCEA Project in Five Low and Middle-Income Countries,” BMC Health Services Research 7 (2007): 108.

47 Bertozzi, S. M., M. Laga, S. Bautista-Arredondo, and A. Coutinho, “HIV Prevention 5: Making HIV Prevention Programs Work,” The Lancet 372, no. 9,641 (2008): 831–844.

48 Birdsall, N., W. Savedoff, K. Vyborny, and A. Mahgoub, Cash on Delivery: A New Approach to Foreign Aid with an Application to Primary Schooling (Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development, 2010).

49 Ibid.