1. The future of AIDS: a still-unfolding global challenge

The world is approaching a moment of truth in the still-unfolding response to the AIDS epidemic.

The worldwide mobilization to combat a disease unheard of 30 years ago has generated historic achievements. For the first time, complex, lifelong management of a chronic disease has been widely implemented in low-income countries, averting millions of deaths.1 Prevention services have also been introduced in antenatal settings to prevent infants from becoming infected, and the overall number of new HIV infections in 2009 for both children and adults was more than 20% lower worldwide than in 1997.2

The pandemic has also elicited an unprecedented global mobilization of political and financial resources. For the first time in history, a United Nations program was established dedicated to fighting a single disease and the first-ever special session of the UN General Assembly was held devoted to a particular health condition. AIDS also led to the creation of a major new addition to global health financing architecture, The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. As of 2008, total annual resources for HIV programs in low- and middle-income countries reached US$ 15.6 billion, an astonishing 53-fold rise in 12 years.3,4 And, by 2010 an estimated 5 million people in low- and middle-income countries were receiving antiretroviral treatment, a remarkable 12-fold increase in less than a decade.5

Against this historic progress, ominous signs suggest that the AIDS response is beginning to fracture. In May 2010, the New York Times profiled Uganda’s biggest AIDS clinic, where stalled funding has prompted authorities to cap the number of patients enrolled in HIV treatment.6 Citing Uganda as the “first and most obvious example of how the war on global AIDS is falling apart,” the Times reported that the “golden window” of worldwide generosity appears to be closing, consigning countless newly diagnosed Ugandans to an early death.

The world has traveled this road before. From the Green Revolution that made acute hunger a thing of the past in scores of countries throughout the world to major initiatives that eradicated malaria from large swathes of the world, the global community has repeatedly mobilized to address global health inequities, only to lose interest or to declare victory prematurely. The results have been catastrophic, especially in Africa, where conditions that have been unknown in upper- and middle-income countries for decades continue to cost millions of lives each year.

Will this same tragic story be repeated with AIDS? Or will decision-makers throughout the world learn from the mistakes of the past and chart a different, healthier, more enlightened course?

In 2031, the world will mark 50 years since AIDS was first reported. Recognizing the generations-long challenge posed by AIDS, UNAIDS launched aids2031 as an independent consortium, composed of experts in public health, economics, biomedicine, the social sciences, international development, and community activism. Organized into nine thematic working groups, the aids2031 Consortium has examined possible futures of the pandemic, the factors most likely to determine its future course, and the steps needed to sharply reduce the number of new HIV infections and AIDS deaths over the next generation.

AIDS: Taking a Long-Term View examines the AIDS challenge, using a future-oriented lens to identify successful strategies that need to be strengthened and ways in which the response to AIDS must change. It directly refutes the growing “AIDS fatigue” reported among key international donors, some national governments, and global opinion leaders, and rejects the either/or choice between focused initiatives to address specific diseases and strengthened broad-based health services. Both approaches are needed.

If the AIDS landscape is to undergo transformation by 2031, when the world marks the 50th anniversary of the initial recognition of the pandemic, AIDS must remain high on the global agenda. A long-term and sustainable response is needed that continues to generate and apply new knowledge.

Reflecting on the past, looking toward the future

The emergence of the epidemic more than a generation ago represented a historic and unexpected development. By the early 1980s, experts believed that the era of infectious disease was fast becoming a relic of an earlier era. While developing countries might continue to grapple with old diseases that had been largely banished from industrialized settings but never brought under control globally—including malaria and tuberculosis—it was assumed that the world overall was entering an epoch when chronic diseases associated with rising affluence would consume the efforts of health planners and medical researchers.

AIDS upset all these expectations and assumptions. In three decades, HIV has infected more than 60 million people worldwide.7 More than 27 million have died of AIDS-related causes. AIDS is the leading cause of death in sub-Saharan Africa and one of the leading causes of death worldwide among reproductive-age women.

The epidemic has inflicted the “single greatest reversal in human development” in modern history.8 In sub-Saharan Africa, home to two-thirds of all people living with HIV, average life expectancy has fallen by more than a decade during the last 20 years as a result of AIDS (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Life expectancy at birth, selected regions 1950–1955 to 2005–2010.

Source: Population Division of the Department of Economics and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat/World Population Prospects.

Although sub-Saharan Africa has been most affected, other regions have not been spared. Even though HIV prevalence in Asia is only a small fraction of that in Africa, the region experienced 300,000 AIDS deaths in 2009.9 Moreover, as Figure 1.2 illustrates, existing trends are not encouraging in Asia and the modes of transmission are changing. The pandemic costs affected Asian households more than US$ 2 billion annually and is projected to cause an additional 6 million Asian households to fall into poverty by 2015.10

Figure 1.2. Past and projected new HIV infections in Asia by population group.

Source: CAA: Redefining AIDS in Asia Technical Annex.

Much is certain about the epidemic’s future. AIDS will remain an enormous global challenge. Even with a robust and much stronger effort to prevent new infections and deliver effective therapies, the disease will undoubtedly remain a major cause of death worldwide. In Southern Africa, AIDS will continue to pose an existential threat to national economies, agricultural sectors, and both urban and rural communities.

Yet much about the future of AIDS remains uncertain. In large measure, the pandemic’s severity in 2031 will depend on choices to be made in the next few years. This chapter summarizes the sobering results of modeling undertaken by the aids2031 Modeling Working Group. If efforts to tackle AIDS become smarter, more focused, and more community centered, tens of millions of lives can be saved over the next generation. If actions to address AIDS instead remain static or weaken over time, the result will be millions of preventable new infections and AIDS will claim many more millions of lives.

Figure 1.3. Annual AIDS deaths (adults 15–49 years) comparing current trends against expanded scenario. The cumulative number of deaths avoided between 2008 and 2031 in the expanded scenario is more than 7 million.

Source: aids2031 Modeling Working Group (unpublished data)

What the history of AIDS may tell us about the future

More than 33.3 million people worldwide are living with HIV, and nearly 5,000 die every day. Each hour, around 200 people die of AIDS. There are around 7,400 new infections every day.11 The statistics are numbing, conveying the extraordinary human toll of the disease.

What was once a new disease has long since become familiar. The well-documented history of the epidemic tells us important facts that are relevant to the future. Consider some of the known facts.

Epidemics often differ radically within and between countries and regions

The so-called “global AIDS epidemic” is, in reality, an amalgamation of multiple local epidemics that often differ markedly from one another. Although women account for 60% or more of all people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, men tend to predominate among HIV cases in most other regions.12 Whereas sexual intercourse is the primary mode of transmission in India overall, extremely high rates of infection are reported among people who inject drugs in certain districts.13 In Benin, Kenya, and Tanzania, the variation between the highest-prevalence district and the lowest is 12-fold, 15-fold, and 16-fold, respectively.14 Meanwhile, HIV prevalence in Côte d’Ivoire is more than twice as high as in Liberia or Guinea, even though these countries share national borders.15

These and other variations teach us is that AIDS programs and policies must address the unique set of circumstances in particular settings. Certain principles may apply to AIDS responses everywhere—such as the value of a rights-based approach or the importance of engaging affected communities in the response—but no cookie-cutter model exists for addressing the broadly divergent types of epidemics around the world.

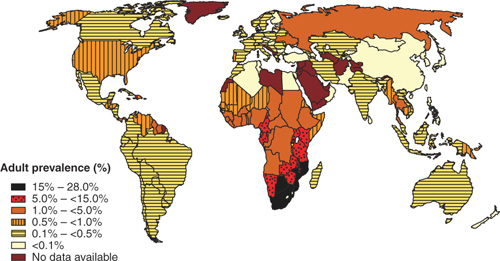

The pandemic is constantly evolving

Even when epidemiological trends appear stable, the pandemic is constantly changing. As Figures 1.4–1.6 illustrate, what began as epidemics with differing characteristics primarily confined to a handful of countries progressively spread to affect the entire world.

Figure 1.4. Progress of the AIDS pandemic, 1990.

Source: Adapted from UNAIDS data.

Figure 1.5. Progress of the AIDS pandemic, 2000.

Source: Adapted from UNAIDS data.

Figure 1.6. Progress of the AIDS pandemic, 2009.

Source: Adapted from UNAIDS data.

Within regions and countries, the nature of individual epidemics has changed over time. In China, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, epidemics that were previously characterized primarily by transmission via injecting drug use are now increasingly driven by sexual transmission.16 In many European countries, epidemics that were earlier concentrated in gay communities have given way to epidemics in which heterosexual adults and immigrants to the region are also at risk of infection.17 As the epidemic has matured and become endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, older adults in stable, long-term relationships now account for the largest share of new infections in many African countries.18

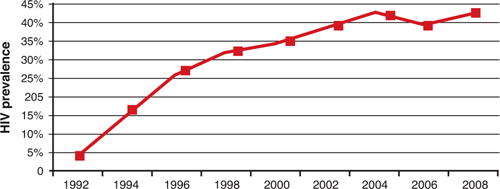

The evolution of each epidemic is affected by its social, economic, and physical environment

Patterns of social and economic life often determine the trajectory of local epidemics. In New York City, a “synergism of plagues,” abetted by the planned shrinkage of municipal services as a result of the city’s acute fiscal crisis in the 1970s, was directly tied to the explosion of HIV in the early 1980s among low-income drug users.19 The astonishing emergence of South Africa’s HIV epidemic in the 1990s—with estimated HIV prevalence rising from less than 1% at the beginning of the decade to nearly 20% by the turn of the century—coincided with the dramatic social and population dislocations associated with the demise of apartheid. In Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the disintegration of the Soviet Union triggered radical shifts in sexual and drug-using behaviors and the rapid deterioration of public health services, contributing to sharp increases in HIV transmission.

The history of human relations and labor patterns in Southern Africa is indelibly tied to the epidemic’s severity in that subregion. The countries with exceptionally high HIV prevalence are generally called “hyperendemic.” Southern Africa is home to nine hyperendemic countries where adult HIV prevalence exceeds 10%, about which the aids2031 Hyperendemic Working Group concludes: “A central historical feature shared by all the hyperendemic countries was the rapid, forced proletarianization of males, the establishment of circular migratory patterns and, post-independence, large-scale urbanization.”20 These trends triggered broad-scale migration of male workers, disrupted households, contributed to high rates of sexual concurrency, and destroyed traditional methods for setting social norms. The eventual results are evident in South Africa’s rapidly growing informal urban settlements, where infection rates are twice the national average.21

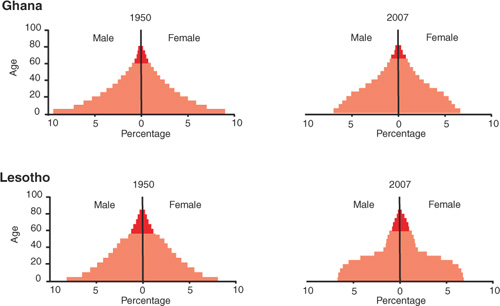

The epidemic has become firmly entrenched in Southern Africa

AIDS is a pressing health challenge for scores of countries, but its effects are especially pronounced in Southern Africa. With just 2% of the world’s population, Southern Africa accounts for 34% of all people living with HIV.22 It is impossible to speak of the future of Southern Africa without discussing the future of AIDS.

As Figure 1.7 reveals, the epidemic has skewed population structures in countries such as Lesotho. The figure for Ghana shows a more typical change in age structure resulting from lowered birth rates and improved life expectancy. By contrast, Lesotho, with one of the world’s highest levels of HIV infection, shows a marked depletion of the population of working-age adults. In hyperendemic settings, the extraordinary loss of adults in their 30s and 40s has interrupted the natural process that imparts learning and values to younger generations, resulting in national populations that consist largely of the very young and the very old. These patterns not only reflect the epidemic’s extraordinary impact, but also illustrate the degree to which AIDS undermines the ability of hyperendemic countries to mount a robust and sustained response to the epidemic.

Figure 1.7. Changes in population structure: Ghana and Lesotho.

Source: Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision.

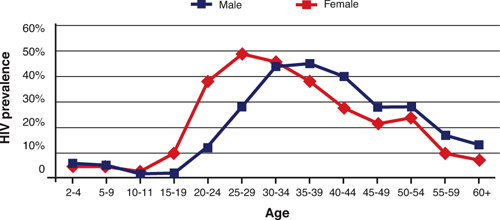

AIDS discriminates

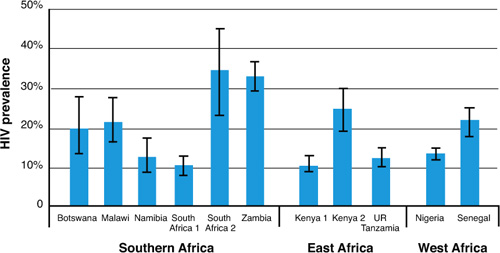

Although AIDS epidemics began among the most affluent in some countries, they almost invariably visit their harshest effects on marginalized groups. Adult HIV prevalence for the world as a whole is 0.7%, yet an estimated 13% of people who inject drugs, 6% of men who have sex with men, and 3% of sex workers are living with HIV.29 Moreover, these global estimates, derived from national surveys, significantly understate the pandemic’s burden on these populations in particular settings. National surveys in Malawi, for example, indicate that more than 70% of sex workers in the country are infected.30 Even in sub-Saharan Africa, where heterosexual intercourse has long been assumed to be the almost exclusive driver of epidemics, recent studies have documented exceptionally high HIV prevalence among these key populations. As Figure 1.10 illustrates, multiple studies have documented levels of HIV infection among men who have sex with men that consistently exceed overall adult HIV prevalence in these settings. In Kenya, men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, and sex workers and their clients account for roughly one in three new HIV infections.31 In Senegal, men who have sex with men are believed to represent up to 20% of all incident infections.32

Figure 1.10. HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in sub-Saharan Africa (2002–2008). [Note: South Africa 1 and 2 and Kenya 1 and 2 refer to the results from different studies.]

Source: WHO/UNAIDS 2009 AIDS epidemic update.

The pandemic’s history cautions us to anticipate unexpected turns over the next generation

Although HIV information systems remain weak in many countries (an issue that Chapter 2, “Generating knowledge for the future,” addresses in some detail), the ability to monitor and understand national epidemics has greatly improved. After experiencing a rapid increase during its first 15 years, the pandemic appears to have stabilized globally, with the annual number of new infections about 20% lower today than in the mid-1990s.33 With the exception of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where new infections continue to increase, the pandemic appears to have stabilized or slowed in most regions.

This apparent stabilization of the pandemic has given rise to a general consensus in the popular media that the future of the pandemic can be projected with some accuracy. AIDS, it is said, has “peaked,” with a slow but steady decline in rates of new infections likely to occur in the foreseeable future.

This emerging confidence in our ability to predict the future of the pandemic ignores previous experience with other infectious diseases and with AIDS itself.34 Studies of endemic syphilis, for example, have documented that waves of infections are common over time, with spikes in incident cases often separated by a decade or more.35 This is especially likely for epidemics that have become concentrated in particular populations. After a sharp decline in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men more than two decades ago in high-income countries, rates of new infections have steadily increased since the early 1990s.36 In part, this reflects the fact that new cohorts of young people enter the population of sexually active adults over time.

Indeed, AIDS has repeatedly defied predictions and is sure to do so in the future. In December 1995, the WHO Global Programme on AIDS erroneously projected that the pandemic’s center would be in Southeast Asia, with more modest growth predicted in sub-Saharan Africa.37 A decade ago, few would have predicted that more than 1 million people would be living with HIV today in the Russian Federation. And certainly few observers foresaw a reversal in Uganda’s longstanding gains in reducing HIV prevalence.38 On the more favorable side of the ledger, only a small number of scientists were prepared for the emergence in the mid-1990s of combination antiretroviral therapy, which, for those who had access to it, rapidly converted the disease from an invariably fatal condition to one that is chronic and manageable.

The pandemic’s past teaches that political, economic, and social shocks can greatly affect the trajectory of AIDS. In this regard, the accelerating rate of population migration in many regions is cause for concern. A study of six Asian countries by the aids2031 Working Group on Countries in Rapid Economic Transition concludes that major, continued population movements, particularly associated with growing urbanization, may facilitate the spread of HIV over the next generation.39 In China alone, 300 million people are expected to migrate over the next 20 to 30 years.40 Although mobility on its own is not a risk factor for HIV, migration often increases risk and vulnerability by disrupting social and familial networks, contributing to sexual risk taking and drug use, and subjecting individuals to violence and discrimination. In Asia, population migration has been strongly linked with the spread of infectious diseases.41

Other changes are also foreseeable. The introduction of antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings is rapidly altering attitudes about AIDS in many parts of the world where infection has long been regarded as a death sentence. Although the availability of treatment is arguably a prerequisite for a strong, sustainable effort to prevent new HIV infections (an issue Chapter 4, “Financing AIDS programs over the next generation,” addresses in greater detail), the health benefits of treatment may also cause some to view the disease with less concern and alarm. In high-income countries, especially among men who have sex with men, evidence indicates that sharp reductions in HIV-related death and illness have contributed to an increase in sexual risk behaviors, ultimately resulting in rises in HIV incidence.42 Were such trends to be replicated elsewhere, the results could be potentially catastrophic.

In short, much about the future of the pandemic remains unclear. This uncertainty necessitates continued vigilance in the AIDS effort worldwide.

AIDS in a changing world

As a disease that is fundamentally linked to the way humans live and how they relate to one another, AIDS is inextricably entwined with the future of our world—and our world is rapidly changing.

Globalization

Regions that once seemed remote from each other have drawn considerably closer as a result of increased international travel, breakthroughs in communications technology, and the internationalization of commerce, social trends, and political groupings. These trends have already had important effects on the pandemic and will continue to do so.

Globalization may bring benefits as well as challenges. Whereas humans have historically concerned themselves primarily with problems in their own countries or communities, the increasing inter-connectedness of our world makes it possible to mobilize global endeavors to address global problems. Thus, an Irish rock star can galvanize global attention on the pandemic’s intense burdens in sub-Saharan Africa, and an African-born player for a major European football club can focus attention on problems in his home country.

A key driver of globalization, the revolution in information and communication technology, is changing the ways people communicate about behaviors and issues.45 Although speaking about the “digital divide” between rich and poor countries is common, this gap is narrowing quickly, as use of the Internet and mobile communications technology is growing fastest in developing countries. Technological advances also may upend historic patterns; in developing countries, for example, women are more likely than men to use SMS text messaging to communicate. As with other aspects of globalization, communications advances may provide new avenues for intervention while at the same time raising new challenges. Social networking technologies offer new ways to mobilize communities and societies to take action, but they may also facilitate increased risk behavior; in some countries, sex work solicitation is rapidly transitioning from brothels, streets, and other traditional venues to the Web and mobile phones.

Globalization also teaches us something else. We sometimes speak as if we are living in a unique moment in human history, but this is not the first era of globalization. Between 1890 and 1913, levels of international trade and financial transactions were comparable to today’s.46 But unforeseen political and economic shocks, including World War I and the Great Depression, brought this earlier era of globalization to an abrupt end. This history reminds us that although we can—and should—do our best to anticipate future trends, unexpected surprises may well be in store, testing our ability to adapt to a radically different set of circumstances.

Climate change

Extreme weather events and other disasters associated with climate change, as well as the increased frequency and severity of droughts in developing countries, are likely to generate up to 150 million climate-change refugees in coming decades47 and further accelerate the exodus from rural villages to urban settings. Although mobility itself is not a risk factor for HIV, large-scale population dislocations frequently place people in situations of increased risk and vulnerability. By exacerbating the degradation of agricultural sectors, climate change may worsen the well-documented effects of AIDS on household food security and agricultural economies in sub-Saharan Africa.

Climate change could have other real, although indirect, effects on the future of AIDS by reducing funding for health programs in low- and middle-income countries. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change projects that developing countries will incur annual costs of adapting to climate change of US$27 billion to 66 billion by 203048; other researchers predict that associated costs will be considerably higher.49 With such extraordinary costs looming, developing countries and external donors may struggle to accommodate other competing needs, such as AIDS, other infectious diseases, or health-systems strengthening.

Population growth

By 2031, the global population is projected to exceed 8 billion people. Countries are already finding that stability in the percentage of the national population infected with HIV translates over time into increasing numbers of people living with the disease. Population growth also has the potential to increase social conflict regarding natural resources such as water or food, which could give rise to greater population mobility and further increase risks of and vulnerabilities to HIV.

A changing global power structure

Existing global structures and mechanisms for AIDS decision-making arose out of political and economic power structures put in place after World War II. The victors in that conflict forged global institutions that have played central roles in the AIDS response, including the United Nations system and the World Bank. The major AIDS donors also have largely reflected the Atlantic orientation of global power in the second half of the 20th century.

These power dynamics are rapidly changing. China, India, and other Asian economies are growing far more rapidly than those represented by the Group of Seven major industrialized countries. Brazil, Russia, South Africa, and other countries are also rapidly coming into their own as global and regional powers, illustrated most vividly by the G20’s replacement of the G7 as a key forum for global decision-making. Meanwhile, the traditional global powers, most recently buffeted by the global financial and economic crisis, confront worrisome structural challenges associated with economic stagnation, long-term budget deficits, and rapidly aging populations.

How these trends will affect the future of AIDS is uncertain. The relative political and economic decline of the donors that have helped underwrite the massive build-up of financial resources for AIDS is a cause for concern, at least. And the transition to a more multipolar world could conceivably make it even more difficult to marshal coordinated global action on major problems. But these trends also offer potential opportunities, as the corresponding development of new global powers offers the prospect of new AIDS donors coming on the scene in future years.

Scenarios for the pandemic’s future

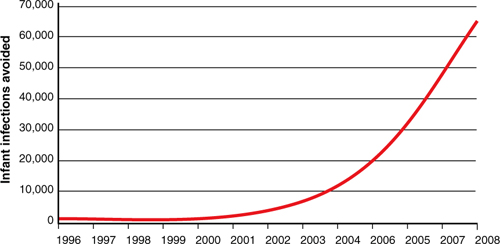

Perhaps the clearest message of the pandemic’s history to date is that concerted action can make a difference. Antiretroviral treatment had saved 2.9 million lives worldwide between 1996 and 2008.50 Similarly, as Figure 1.11 shows, expanded access to services to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission averted at least 200,000 new infections globally between 1996 and 2008, with these life-saving results increasing from year to year as services have been expanded.51

Figure 1.11. Estimate of the annual number of infant infections averted through the provision of antiretroviral prophylaxis to HIV-positive pregnant women globally (1996–2008).

Source: WHO/UNAIDS 2009 AIDS epidemic update.

The magnitude and quality of the continued response to AIDS will be determining factors in the pandemic’s future. To clarify the long-term implications of choices to be made in the coming years, the aids2031 Modeling Working Group produced a series of mathematical models on potential AIDS futures in 22 countries, including 12 in Africa (Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Zambia), six in Asia (Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam), two in Eastern Europe (Russia and Ukraine), and two in Latin America (Brazil and Mexico). For each of these countries, the model took into account the interaction between different sexually transmitted diseases and HIV, the role of heterogeneity in sexual behavior, patterns of sexual acts within partnerships, networks of concurrent sexual partnerships, patterns of incidence as a function of age, and the impact of interventions. For intervention impact, the modelers relied on the public health literature, including clinical trials and epidemiological studies; the models all assumed constant coverage and impact from 2015 onward. Models further assumed that receipt of antiretroviral therapy would reduce the likelihood of onward HIV transmission, a conclusion that is consistent with numerous studies that have correlated viral load with transmissibility.

Using these various data sources, modelers charted the likely future of epidemics in these 22 countries according to various scenarios, calculating the number of incident infections, total HIV prevalence in 2031, and the number of AIDS deaths likely to occur under each scenario between 2010 and 2031. Importantly, the models aim to quantify the long-term impact of choices that will be made in the next several years, tracing the ultimate impact in 2031 to political choices made between 2010 and 2015. One possible future scenario, the “status quo” scenario, calculates results based on a continuation of current coverage levels. A second scenario envisages an intensification of HIV prevention and treatment programs toward saturation coverage.

The results of the modeling exercises led to several fundamental conclusions about the epidemic’s future and the choices facing global decision-makers over the course of the next several years.

Choices made in the next five years will profoundly affect how the pandemic will look in 2031

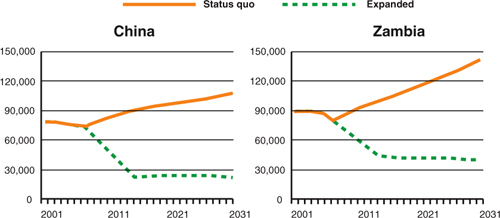

Maintaining existing coverage levels would allow nearly 50 million cumulative new infections among 15- to 49-year-olds in these 22 countries by 2031. By contrast, as shown in Figure 1.12, expanded coverage would avert more than 26 million of these infections (or more than half).

Figure 1.12. Projection of new HIV infections and number of adults infected according to status quo and an expanded scenario based on information received from 22 countries.

Source: aids2031 Modeling Working Group (unpublished data)

The impact of these choices in specific countries is revealing. Consider South Africa, for example, home to the world’s largest number of people living with HIV. If current coverage levels continued, HIV prevalence in 2031 would be the same (18%) as it was in 2008, the most recent year for which data is available.52 Yet this stability in prevalence is deceiving; with the projected growth in population, a stable prevalence would mean 12 million new infections between now and 2031. By contrast, if AIDS response efforts are strengthened over the next several years, HIV prevalence would be one-third lower in 2031, assuming that scaled-up treatment will help slow the rate of new infections by lowering the level of virus circulating in communities. In Nigeria, Mozambique, and Zambia, reductions would be even sharper, with projected prevalence in 2031 nearly 50% lower under an intensified response. The flattening of all the curves after 2015 reflects the assumption that all intervention coverage and impacts is constant after that date.

In Zambia, the annual number of new infections in 2031 would be nearly four times greater with a continuation of current service coverage than with an intensified, expanded response, as Figure 1.13 shows. In China, where population growth will be a critical driver in the number of new HIV infections over the next generation, the status quo scenario would result in more than three times as many incident infections in 2031 as in an expanded response, also shown in Figure 1.13. HIV-related deaths in Zambia would be more than twice as high in 2031 if current coverage levels continue, and the mortality rate in China would be more than three times as high.

Figure 1.13. Current and projected annual new HIV infections in adults (15–49 years) in China and Zambia, according to different scenarios.

Source: WHO/UNAIDS 2009 AIDS epidemic update.

To achieve dramatic change, all available tools must be used to their maximum advantage

To avert tens of millions of deaths over the next generation, as projected in the most favorable scenario, the best results possible must be obtained with the available tools. This demands continuous quality improvement, results-based management, and program evaluation to improve performance over time (see Chapter 3, “Using knowledge for a better future”). Such improvements over time could be expected to continue beyond 2015, leading to better future results than shown in the projections.

Prioritizing HIV prevention is critical to accelerated progress between now and 2031

The level of resources devoted to HIV treatment in low- and middle-income countries is roughly 2.5 times greater than amounts dedicated to HIV prevention.53 Increasingly, AIDS efforts are characterized by an approach that focuses almost exclusively on treating existing infections and devotes meager resources to preventing new infections. This approach mimics the path high-income countries have taken. In the United States, for example, only 3% of government outlays for HIV are currently allocated to prevention programs.54 Without substantial targeted HIV prevention efforts, new HIV infections will continue to outpace treatment efforts—even while recognizing some prevention efforts from expanded treatment.

Figure 1.14 demonstrates that the long-term results of this approach would be potentially devastating in resource-limited settings. In Zambia, nearly twice as many incident infections would occur in 2031 under a treatment-only approach as would occur with a combination of robust prevention and treatment efforts.

Figure 1.14. Current and projected impact of intervention strategies on new HIV infections among adults in Zambia.

Source: aids2031 unpublished data.

To achieve optimal results for 2031, new prevention tools will be needed

To make truly revolutionary gains in the epidemic over the next two decades, new and better prevention tools are needed, along with structural changes in many communities and societies. According to the aids2031 Modeling Working Group, achieving a 90% reduction in HIV incidence by 2031 necessitates a 70% reduction in the average number of sexual partners.55 This effect far exceeds results obtained with existing prevention tools, pointing to the need for additional prevention options and a broader approach to prevention that accounts for social drivers of national epidemics.

Figure 1.12 is telling. With an expanded response that achieves maximum coverage for both HIV prevention and treatment, the annual number of new HIV infections in Zambia would be half what it was in 2001 and roughly 50% lower than current HIV incidence. This would represent significant progress, but it would still leave Zambia grappling with an enormous health crisis that would sap national resources and push countless households into poverty.

The world should aim higher. However, reaching this lofty goal will require new scientific tools and improved knowledge about ways to change sexual behavior and prevent new infections, topics that the following chapter addresses in depth.

Delivering treatment to those who need it will be vital to minimizing the pandemic’s impact

Securing the gains envisaged in the intensified/expanded scenario will require continued, sustained support for scaling up HIV treatment. As Figure 1.15 illustrates, current coverage trends would cover fewer than half the number of people who would receive treatment under the optimal scenario in 2016. By 2031, the number of people receiving treatment in the optimal scenario would be more than 60% higher than with current trends.

Figure 1.15. Current and projected number of adults (15–49 years) receiving treatment in Zambia.

Source: aids2031 unpublished data.

These projections underscore the need to intensify measures to mitigate the pandemic’s impact

An important lesson learned thus far in the global AIDS response is that even the most heavily affected societies have proven to be far more resilient than projected earlier in the epidemic.56 Yet this resilience masks enormous individual and societal burdens, many of which are likely to endure for generations.

A case in point is the extraordinary number of the world’s children who have been orphaned by the pandemic. In sub-Saharan Africa, more than 14.8 million children have lost one or both parents to AIDS.57 As the projections summarize, vulnerable households will still face significant numbers of deaths and further burdens, even under the most favorable scenarios.58

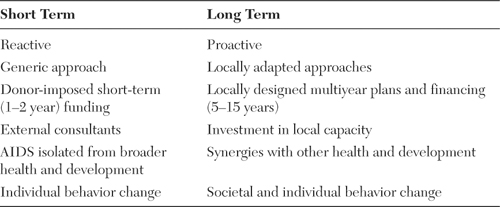

Over the last three decades, the primary focus of the AIDS response has been on getting programs up and running, frequently in communities with little health infrastructure. In many cases, the goal has been to achieve immediate results. In some cases, responses have been premised on the expectation that an imminent biomedical breakthrough will resolve the need for further action. Typically, more difficult challenges—such as changing community norms or gender relations, or addressing the impact of labor or economic structures on individual or collective vulnerability—have been dismissed as too long range and time-intensive to merit investment in the context of an emergency.

The overarching theme of this report is that AIDS is a generations-long challenge and thus requires a generations-long response that adopts a longer-term mindset. In moving forward, the imperative of scaling up must be matched by an equally strong commitment to quality, efficiency, and sustainability. And, to achieve long-term success with AIDS, underlying drivers of national and local epidemics must be addressed, even if these efforts are unlikely to achieve results in the short term. Table 1.1 details the characteristics of the long-term and short-term approaches.

Table 1.1. Selected characteristics of shifting from a short-term to long-term approach

As with any effort that must be sustained over many years, complacency and denial are the enemies of long-term success; already, signs of the world’s fading interest in AIDS are apparent. But with concerted efforts and a changed approach as described in this book, success in the AIDS response is achievable. A great deal of the knowledge needed to radically reduce the number of new HIV infections and AIDS deaths over the next generation is already available, and the world possesses the research capacity to generate the new preventive and therapeutic tools that will be required. Even in the midst of worldwide economic uncertainty and anxiety, little doubt arises that sufficient resources exist to address AIDS and other global health challenges.

The subsequent chapters detail the steps needed to place a global AIDS response on a long-term and sustainable footing. In the final chapter, the aids2031 Consortium offers recommendations for the steps that need to be taken now to ensure long-range success.

Endnotes

1 UNAIDS and WHO, AIDS Epidemic Update (Geneva: UNAIDS and WHO, 2009).

2 UNAIDS, AIDS Info: UNAIDS Reference Report (Geneva: 2010).

3 UNAIDS and the Kaiser Family Foundation, Financing the Response to AIDS in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: International Assistance from the G8, European Commission, and Other Donor Governments in 2009, July 2010. Accessed 2 August 2010 at http://www.kff.org/hivaids/7347.cfm.

4 UNAIDS, Report on the Global HIV Epidemic (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2006).

5 UNAIDS, MDG6: Six Things You Need to Know about the AIDS Response Today (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2010).

6 McNeil, D. G. “At Front Lines, AIDS War Is Falling Apart,” The New York Times, 10 May 2010. Accessed 16 June 2010 at www.nytimes.com/2010/05/10/world/africa/10aids.html.

7 UNAIDS and WHO, AIDS Epidemic Update (Geneva: UNAIDS and WHO, 2009).

8 UNDP, Human Development Report (New York: United Nations Development Programme, 2005).

9 UNAIDS, AIDS Info: UNAIDS Reference Report (Geneva: 2010).

10 Commission on AIDS in Asia, Redefining AIDS in Asia: Crafting an Effective Response (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2008).

11 UNAIDS, MDG6: Six Things You Need to Know about the AIDS Response Today (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2010).

12 UNAIDS and WHO. 2009. Op cit.

13 National AIDS Control Organisation, HIV Sentinel Surveillance and HIV Estimation in India 2007: A Technical Brief, 2008. Accessed 22 June 2010 at www.nacoonline.org/Quick_Links/Publication/.

14 UNAIDS and WHO. 2009. Op cit.

15 UNAIDS, Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2008).

16 UNAIDS and WHO. 2009. Op cit.

17 Ibid.

18 Khobotlo, M., R. Tshehlo, J. Nkonyana, M. Ramoseme, et. al., Lesotho: HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis (Maseru, Lesotho: Lesotho National AIDS Commission, 2009); Gelmon, L., P. Kenya, F. Oguya, B. Cheluget, and G. Haile, Kenya: HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis (Nairobi, Kenya: National AIDS Control Council, 2009); Mngadi, S., N. Fraser, H. Mkhatshwa, T. Lapidos, et. al., Swaziland: HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis (Mbabane, Swaziland: National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS, 2009); Bosu, W., K. Yeboah, G. Rangalyan, K. Atuahene, et. al., Modes of HIV Transmission in West Africa: Analysis of the Distribution of New HIV Infections in Ghana and Recommendations for Prevention (Accra: Ghana AIDS Commission, 2009); Asiimwe, A., A. Koleros, and J. Chapman, Understanding the Dynamics of the HIV Epidemic in Rwanda: Modeling the Expected Distribution of New HIV Infections by Exposure Group (Kigali, Rwanda: National AIDS Control Commission, MEASURE Evaluation, 2009).

19 Wallace, R., “A Synergism of Plagues: ‘Planned Shrinkage,’ Contagious Housing Destruction, and AIDS in the Bronx,” Environment Research 47, no. 1 (1988): 1–33.

20 aids2031 Hyper-Endemic Working Group, Turning Off the Tap: Understanding and Overcoming the HIV Epidemic in Southern Africa (Johannesburg, South Africa: Nelson Mandela Foundation, 2010. http://www.nelsonmandela.org/index.php/publications/full/turning_off_the_tap_understanding_and_overcoming_the_hiv_epidemic_in_southe/ (Accessed August 6, 2010)

21 Shisana, O., T. Rehle, and L. Simbayi, South African National HIV Prevalence, HIV Incidence, Behaviour, and Communication Survey (Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press, 2005).

22 UNAIDS, AIDS Info: UNAIDS Reference Report (Geneva: 2010).

23 Whiteside, Alan, with Alison Hickey, Jane Tomlinson, and Nkosinathi Ngcobo, “What is driving the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Swaziland? And what more can we do about it?” Report prepared for the National Emergency Response Committee on HIV/AIDS and UNAIDS, Mbabane, April 2003. NERCHA, UNAIDS, and the World Bank Global HIV/AIDS Programme, Swaziland HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis, NERCHA Mbabane Swaziland, March 2009.

24 National Emergency Council on HIV/AIDS, Swaziland HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis Study, National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS (NERCHA) Mbabane Swaziland, March 2009, p. 38.

25 Andrews, Penelope E., Who’s Afraid of Polygamy? Exploring the Boundaries of Family, Equality, and Custom in South Africa, unpublished paper.

26 NERCHA 2009. Op cit p. 40.

27 Whiteside, Alan, and Greg Wood, Socio-Economic Impact of HIV/AIDS in Swaziland, Ministry of Economic Planning and Development, Government of Swaziland, 1994.

28 Whiteside, A., and A. Whalley, Reviewing ‘Emergencies’ for Swaziland: Shifting the Paradigm in a New Era, Durban: HEARD, 2007.

29 WHO, UNICEF, and UNAIDS, Towards Universal Access: Scaling Up Priority HIV/AIDS Interventions in the Health Sector. Progress Report (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009).

30 Government of Malawi, Malawi HIV and AIDS Monitoring and Evaluation Report: 2008–2009, 2010. Accessed 14 June 2010 at http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/malawi_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf.

31 Gelmon, L., P. Kenya, F. Oguya, B. Cheluget, and G. Haile. Kenya: HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis (Nairobi, Kenya: National AIDS Control Council, 2009).

32 Lowndes, C. M., M. Alary, M. Belleau, W. K. Bosu, et. al., West Africa HIV/AIDS Epidemiology and Response Synthesis: Implications for Prevention (Washington, DC: World Bank Global HIV/AIDS Program, 2008).

33 UNAIDS and WHO. 2009. Op cit.

34 Anderson, R. M., S. Gupta, and W. Ng, “The Significance of Sexual Partner Contact Networks for the Transmission Dynamics of HIV,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 3, no. 4 (1990): 417–429.

35 Grassly, N. C., C. Fraser, and G. P. Garnett, “Host Immunity and Synchronized Epidemics of Syphilis Across the United States,” Nature 433 (2005): 417–421.

36 Hall, H. I., R. Song, P. Rhodes, J. Prejean, et. al., “Estimation of HIV Incidence in the United States,” Journal of the American Medical Association 300, no. 5 (2008): 520–529.

37 Mann, J., and D. J. M. Tarantola, eds., AIDS in the World II: Global Dimensions, Social Roots, and Responses, vol. 2 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

38 UNAIDS and WHO. 2009. Op cit.

39 aids2031 Working Group on Countries in Rapid Transition in Asia, Asian Economies in Rapid Transition: HIV Now and Through 2031 (Bangkok, Thailand: UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Asia and the Pacific, 2009).

40 Statement by Dr HAO Linna, Director-General for International Cooperation of the National Population and Family Planning Commission of China at the General Debates of the 41st Session of the UN Commission on Population and Development (New York: 8 April 2008). Accessed on 30 September 2010 at http://www.un.org/esa/population/cpd/cpd2008/comm2008.htm (China statement on Agenda Item 3).

41 aids2031 Working Group on Countries in Rapid Transition in Asia, Asian Economies in Rapid Transition: HIV Now and Through 2031 (Bangkok, Thailand: UNAIDS Regional Support Team for Asia and the Pacific, 2009).

42 UNAIDS and WHO. 2009. Op cit.

43 Levin, A. M., D. T. Scadden, J. A. Zaia, and A. Krishnan, “Hematologic Aspects of HIV/AIDS,” Hematology (2001): 463–478.

44 Fraser, C., T. D. Hollingsworth, R. Chapman, F. de Wolf, and W. P. Hanage, “Variation in HIV-1 Set-point Viral Load: Epidemiological Analysis and an Evolutionary Hypothesis,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, no. 44 (2007): 17,441–17,446.

45 Cranston, P., and T. Davies, Future Connect: A Review of Social Networking Today, Tomorrow, and Beyond and the Challenges for AIDS Communicators (South Orange, N.J.: Communication for Social Change Consortium for aids2031 Communication Working Group, 2009).

46 Quinn, D. P., “Capital Account Liberalization and Financial Globalization: A Synoptic View,” International Journal of Finance & Economics 8 (2003): 189–204.

47 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2007 Report (Geneva: IPCC, 2007).

48 UNFCC, Investment and Financial Flows to Address Climate Change (Bonn, Germany: Climate Change Secretariat, 2007).

49 Parry, M., N. Arnell, P. Berry, D. Dodman, et. al., Assessing the Costs of Adaptation to Climate Change: A Review of the UNFCC and Other Recent Estimates (London: International Institute for Environment and Development and the Grantham Institute for Climate Change, Imperial College, 2009).

50 UNAIDS and WHO. 2009. Op cit.

51 Ibid.

52 UNAIDS and WHO. 2008. Op cit.

53 Izazola-Licea, J. A., J. Wiegelmann, C. Arán, T. Guthrie, P. De Lay, and C. Avila-Figueroa, “Financing the Response to HIV in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 52, no. S2 (2009): S119–S126.

54 Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, U.S. Federal Funding for HIV/AIDS: The President’s Fiscal Year 2011 Budget Request, 2010. Accessed 25 May 2010 at www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/7029-06.pdf.

55 Garnett, G. P., K. Case, T. B. Hallett, J. Stover, and P. K. Piot, “Modeling the HIV Pandemic up to 2031: From an Epidemic to an Endemic Disease,” unpublished paper.

56 UNAIDS and WHO. 2009. Op cit.

57 UNAIDS, AIDS Info: UNAIDS Reference Report (Geneva: 2010).

58 Nigeria National Agency for the Control of AIDS, United Nations General Assembly Special Session Country Progress Report, Reporting Period January 2008–December 2009.