Monthly Closing Procedures

10.1 The Closing Process

10.2 Closing Cash Journals

10.3 Closing Employee Accounts

10.4 Developing a Trial Balance

10.5 Adjusting Entries

10.6 The Adjusted Trial Balance

10.7 Generating Financial Statements

Accounts and Operations

Financial Statements

This subchapter provides an overview of the monthly closing process and walks you through the steps involved. We summarize standard monthly closing procedures for accounts and operations as well as how to process interim (monthly) financial reports.

Accounts and Operations

Chances are, the end of the month at your business is a fairly busy time. Even if your company doesn’t produce monthly financial statements, certain bookkeeping tasks must be performed every 30 days or so, including:

• Sending customer statements

• Reviewing and paying bills as necessary

• Making tax payments

SEE ALSO 12.1, “Advanced Planning”

SEE ALSO 12.2, “Payroll Taxes”

• Processing employee expense reports

• Updating employee records

• Reconciling your bank accounts

SEE ALSO 3.4, “Preparing a Bank Reconciliation”

Some of these procedures are covered in separate chapters, as noted. The rest, and how to coordinate them with your closing duties, are detailed in the sections that follow.

Financial Statements

All organizations have to produce financial statements at least once a year for many purposes. Large public companies must file quarterly as well. And in practice, many businesses choose to generate monthly financial reports to keep tabs on how they’re doing.

Procedures vary from firm to firm, but the steps you use to summarize data from transactions into financial statements are fairly standard:

1. Summarize and total journals. Reconcile to supporting accounts or ledgers.

2. Post reconciled totals to the general ledger. Compute general ledger balances for each account.

3. Compile a trial balance using general ledger balances. Be sure debits equal credits. If they don’t, go back and check postings to locate source of imbalance.

4. Prepare adjusting entries to ensure all costs and revenues are recorded in the proper period. Record to general journal, and post to general ledger.

5. Use revised general ledger balances to prepare the adjusted trial balance.

6. If you’re preparing interim financial statements (those for periods prior to the end of the year), you can take the numbers directly from the trial balance and plug them into the balance sheet and income statement.

To reconcile means to verify that account totals agree with supporting data or calculations.

The trial balance is a listing of the general ledger accounts to see if total debits and credits are equal.

Adjusting entries are journal entries typically made at the end of the period to be sure costs and revenue match and are recorded in the proper period and correct any errors in the general ledger accounts.

The adjusted trial balance is a listing of general ledger accounts that have been adjusted and corrected to see if they balance.

In the rest of this chapter, we take you through these steps in detail. But feel free to flip back to our list at any time if you want to know where you are in the process.

Cash Receipts and Sales

Cash Disbursements and Purchases

This subchapter focuses on closing the books and making sure all activity is properly summarized and posted. We discuss sending monthly statements, paying bills, and recording credit card costs. In addition, you learn how to close cash journals, post to the general ledger, and reconcile account totals with supporting data.

Cash Receipts and Sales

The totals from your cash receipts and sales journal need to be reconciled and posted to the general ledger at the end of the month. But before you get to that point, you need to perform other bookkeeping duties first.

Generating Monthly Statements

Although it’s not required, it’s good business practice to compile a monthly accounts receivable aging schedule to check on the status of outstanding customer accounts. This not only enables you to keep tabs on how well customers are paying their bills, but it can be converted into statement information for your monthly billing. (Most accounting software programs automatically generate statements from aged balances.)

SEE ALSO 4.3, “Accounts Receivable”

The Hobby Company doesn’t have a lot of open accounts, so management probably has a pretty good handle on who is behind on payment. But we’ve included an aging schedule for 10/31 as an example:

THE HOBBY COMPANY

A/R AGING SCHEDULE

OCTOBER 31

The Hobby Company should talk to Fun, Inc., about why they haven’t paid their bill for $580. It is already over 90 days old, which is too old to let pass and could suggest a problem. The end of the month is a good time to analyze accounts to determine where to concentrate your collection efforts and who might need to be cut off. At the end of this process, you’d be ready for billing. The monthly statement for Fun, Inc., generated from this data would look like this:

SEE ALSO 4.3, “Accounts Receivable”

Recording Credit Card Fees

If your business accepts credit cards, you will have an additional fee to record at the end of the month. Credit card companies can charge a variety of fees, from a monthly percentage of sales, to charges for customer support, securing internet transactions, and handling disputed accounts. This is why it’s so important to shop around initially when pricing credit cards, and be sure you’re aware of all monthly charges upfront.

You’ll find the fee amount listed as a charge on the monthly statement you receive from the bank processing your transactions. If, for example, you had credit card sales of $5,500 and a 5 percent fee, your monthly charge would be $275, which you would record with the following entry:

If your bank statement isn’t available at closing time, you might be able to make an entry based on total credit sales. This is called an accrual.

SEE ALSO 10.5, “Adjusting Entries”

Summarizing the Cash and Sales Journal

Throughout the month, you’ve been recording cash taken in from sales, customer payments, and other transactions in either a cash receipts journal or cash and sales journal.

SEE ALSO 4.1, “Recording Sales”

Unless you sell only a few high-ticket items—say luxury goods or specialized machinery or vehicles—it’s unlikely that you’ll journalize sales individually. Not only is it impractical, it’s also inefficient. Most retailers, for example, record sales on a daily basis after totaling cash register tapes. Manufacturers compile a daily sales summary. As an example, let’s look at the October cash and sales journal for The Hobby Company. The Hobby Company sells gaming systems and records sales on a twice-weekly basis.

At the end of the month, Hobby totals each of these columns and then cross-foots (adds the column totals together) to be sure the debits equal credits. (Note: In the case of the Miscellaneous column, these items are added for balancing purposes only. The individual amounts are recorded to the accounts listed in the posting reference column.)

THE HOBBY COMPANY

CASH AND SALES JOURNAL

Because the totals balance, we know Hobby’s accountant recorded the appropriate amounts of debits and credits. If the totals hadn’t agreed, Hobby would have had to go back to the original transactions to find the mistake. An automated system would automatically reconcile these totals, but if there were an error you would still likely have to review the initial transactions.

SEE ALSO 15.1, “Benefits of Computerized Accounting”

At 10/31, Hobby will post the following to the general ledger:

Reconciling Accounts

You’ve determined that Hobby’s cash receipts journal columns cross-foot and have posted the monthly sales to the general ledger. Next you’ll want to be sure the company’s accounts receivable balance in the general ledger reconciles with the accounts receivable subledgers. The subledger contains the individual records for each customer’s account, so all you need to do is add them up.

SEE ALSO 4.3, “Accounts Receivable”

For example, the general ledger account for accounts receivable appears as follows at the end of the month:

Now we would have to go to the subledger and tally the individual customer account balances to see if they agree. (Again, in a computerized system this would be done automatically.) For the sake of simplicity, we’ll assume The Hobby Company only has three open customer accounts:

Account 124, TR Crow Co., has been paid off, so the only subsidiary ledger balances carried forward are from accounts 121 and 123. When added, these amounts should agree with total accounts receivable per the general ledger if the entries have been posted correctly.

The accounts receivable ledger and subsidiary ledgers are in balance, so we can move on. If there had been a difference, we would have checked the math and made sure each transaction was entered properly.

Cash Disbursements and Purchases

Just as with cash receipts, you’ll keep track of cash payments made to purchase inventory or fixed assets or to pay various expenses in a specialized journal called the cash disbursements journal. The totals from this record will be posted to the general ledger at the end of the month, after certain bookkeeping duties are taken care of.

Reviewing Accounts Payable

The end of the month is a good time to review your accounts and be sure you’re paying all bills in a timely manner. Some companies find it useful to prepare an aging schedule, which shows how much you owe and for how long. If your company uses a voucher system, you can compare vouchers paid to checks that have been written.

SEE ALSO 6.4, “Cash Disbursements”

You should also review both paid and unpaid bills to determine that all have been recorded in the appropriate period. Any amounts owed but not yet paid, which are known as accruals, need to be recorded in this month’s accounts.

SEE ALSO 10.4, “Developing a Trial Balance”

Temporary Holding Accounts

Sometimes you have to pay a bill before knowing how the costs are going to be allocated. For example, if you use an outside payroll service, you are often required to remit the amount to them for total payroll, before they’ve sent you the detail of how it breaks down. In this case, you might post the disbursement to a holding account until you have the full details. This is often called a suspense account or a temporary distribution account.

When you’ve received the proper documentation, you’re able to reverse the amount in this account and debit it to the proper expenses. At the end of the month, you should review this account to determine adjusting entries that need to be made. List the remainder on the income statement as miscellaneous expenses.

Summarizing the Cash Disbursements Journal

During the month, The Hobby Company records all purchases and cash outlays in the cash disbursements journal as shown on the next page.

Just as with the cash and sales journal, at the end of the month, the columns are tallied and the totals are posted to the general ledger. Some companies do not include payroll in their cash disbursements ledger, choosing to make biweekly journal entries as it is paid out, and post to the general ledger separately. But for the purposes of this example, we recorded all disbursements into the cash disbursements journal and summarized them into the following journal entry.

Whether The Hobby Company uses the preceding entry or records payroll separately, as we do in the next section, the net result will be the same.

THE HOBBY COMPANY

CASH DISBURSEMENTS JOURNAL

You also need to reconcile the balance in accounts payable in the general ledger with the amounts in the accounts payable subledger (or voucher register if you use that system). This is similar to what you did with accounts receivable earlier.

The balance in accounts payable for The Hobby Company at 10/31 was $2,960. The subsidiary ledgers carried balances of $1,100, $700, $1,050, and $110, which total $2,960. So the accounts reconcile. If they had not, you would have checked your math first and then made sure all transactions were recorded properly.

10.3 Closing Employee Accounts

Reviewing Employee Expense Accounts

Updating Employee Records

Posting Payroll

At the end of the month you will perform certain activities related to payroll. Employee expense accounts must be filed and approved for payment, payroll should be posted, and employee accounts need to be updated for wages and benefits. This subchapter takes you through these tasks and shows you how to prepare the monthly adjusting entry for payroll.

Reviewing Employee Expense Accounts

If employees at your company incur expenses in the course of business, they need to file expense reports for reimbursement. Each business has its own criteria for determining what a business expense is, but standard business expenses include the following:

• Travel

• Entertainment

• Auto (for mileage or gasoline on company business)

• Supplies

Not coincidentally, these are also the items the IRS considers business expenses for tax purposes.

SEE ALSO Chapter 12, “Taxes”

SEE ALSO 14.4, “The Operating Expenses Budget”

Your company should have a system in place so employees can file for reimbursement. Standard procedure is to require employees to itemize expenses on an expense report and attach receipts. These reports are then forwarded to a supervisor for review and approval.

Many companies process reports close to the end of the month, for purposes of efficiency and comparing different employees’ expenses. This process also makes it easier for accounting to prepare a summary journal entry allocating these expenses to their various accounts. For example, in October, assume The Hobby Company had employees submit expense reports for a total of $1,250. This included travel and entertainment of $900, auto expenses of $250, and supplies expenses of $100. After noting the supervisor’s approval on the report, Hobby’s accountant approves the reports for payment. The company would need to record the following entry at 10/31:

Large companies might break down the expenses even further into travel, lodging, meals, and entertainment. But because Hobby only has about 20 employees, 3 of whom incur expenses, fewer accounts are used for simplicity.

Updating Employee Records

The end of the month is also a good time to update employee records. This includes …

• Making necessary postings to the employee earnings reports from the payroll register.

• Updating benefits to reflect new vacation time earned, days taken, absences, etc.

• Making changes or alterations to benefits as allowed from written employee request. This includes, for example, updates to health-care allowance accounts.

Part of closing payroll involves processing employee expense reports. You’ll want to be sure you’ve laid out clear guidelines for allowed expenses and supporting documentation and then have someone in a supervisory position review and approve all reports filed. The end of the month is also a good time to update payroll records on pay rates, benefits, and so on.

Posting Payroll

There are a couple ways to close payroll, depending on how your system is set up. You can do it the way The Hobby Company did in the previous section. After posting payroll biweekly to the cash disbursements journal, payroll and the rest of cash disbursements for the month are summarized to the general ledger. Other companies handle payroll separately and post monthly to the general ledger from the payroll register.

SEE ALSO 8.2, “Computing Wages”

SEE ALSO 8.5, “Recording Payroll”

If The Hobby Company recorded payroll separately in the payroll register, it would use the following alternative entry to record payroll for the month:

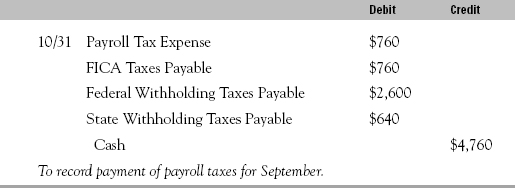

Companies also need to ensure that any payroll taxes for the previous period have been remitted and paid by the end of the month. Federal and state withholding taxes and FICA taxes must be deposited at least monthly, which means a company should be making a minimum of one payment each month. This payment includes both the federal and state withholding and FICA taxes deducted from employee paychecks as well as the company’s share of FICA taxes.

SEE ALSO 8.4, “Employer Payroll Taxes”

Let’s assume The Hobby Company had the same payroll taxes payable in September that it did in October. The entry to record the tax payment for September, which it would make at the end of October when its taxes were due, would be as follows:

Note that the entry is essentially a reversal of the tax liabilities in the initial journal entry. In addition, The Hobby Company records the payroll tax expense for its share of FICA and deducts the total amount of tax paid from cash. As a final step, because the last pay period ended on October 24, it’s necessary to make an accrual for the wages to be paid on November 2.

SEE ALSO 10.5, “Adjusting Entries”

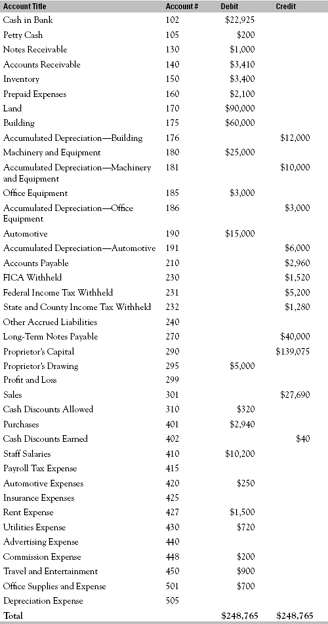

10.4 Developing a Trial Balance

After you’ve reconciled the journal balances and made sure all monthly activity is correctly posted to the general ledger, it’s time to do what is called a trial balance. This trial balance isn’t a public document. Rather, it’s a tool to help you determine if the accounts are in balance before you adjust them and prepare financial statements.

To compile the trial balance, list the ending balances from each of the general ledger accounts. The initials near the entries indicate the journal that the entry was posted from. CD is cash disbursements journal, CR is cash and sales journal, GJ is general journal.

The balances from each general ledger account are carried forward to the trial balance. Accounts here are set up in order: balance sheet first and then income statement. Some accounts such as depreciation have zero balances at this point because adjusting entries have not yet been made. We cover how to make adjusting entries in the next subchapter.

The important thing at this point is that the general ledger balances are properly computed and transferred to the correct accounts in the trial balance. A computerized system will do this automatically for you.

THE HOBBY COMPANY TRIAL

BALANCE AS OF 10/31

We are fortunate that in this trial balance the Debit and Credit columns equal. If they had not been—as is often the case—we would have had to troubleshoot to find the source of the error before we moved on.

Some common ways accountants check for errors include …

• Checking to see if the difference is divisible by 9. If it is, two digits in one of the numbers might have been reversed.

• Verifying that if the difference is 10 or 100, a 0 wasn’t added where it shouldn’t be.

• Dividing the difference in half. If the answer is a number on the trial balance, perhaps a debit or a credit has been misclassified.

By the time you’re putting together the trial balance, you’ve come pretty far along the accounting cycle. You’ve recorded your transactions, summarized them for the period (a month in this case), and posted them to the general ledger. Once you transfer these numbers to the trial balance, you can start to see your company’s financial situation and how you’ve performed. Now you’re ready to make your final adjustments.

Identifying Adjusting Entries

Recording Accruals

Working with Deferrals

The purpose of adjusting entries is to ensure that all transactions are recognized in the proper period. In this subchapter, we cover the various types of adjusting entries and how to make them.

Identifying Adjusting Entries

At the end of each month, you will need to adjust accounts that have had activity that’s not yet been recorded. Some adjustments such as depreciation, amortization, and interest are made regularly. These are usually a set amount, so the entries should be fairly straightforward. In fact, in computerized accounting systems they are typically referred to as recurring entries and can often be set up to be made automatically each month. Others, such as expenses incurred, but not paid and unearned revenues, will require some digging. You will need to look at unpaid bills, for example, to see if any are due. Or consider prepayments made on service contracts that won’t finish for months.

Over time, you will develop a list or special journal of entries you commonly need to adjust, and the monthly process should become routine.

Recording Accruals

Accruals—which affect revenue and expense accounts—are among the most common adjusting entries. Unless you’re using the cash method of accounting, you most likely need to record accruals at the end of the month. You will use these records to adjust the books for expenses that have been incurred but not paid and revenues that have been earned but payment is not yet due from a customer.

SEE ALSO 2.2, “Timing”

For example, if The Hobby Company has telephone charges of $150 for October but does not receive the bill until early November, an accrual must be set up as follows to recognize the expense in the October financial statements:

Most likely, The Hobby Company would have discovered the need for this entry by reviewing monthly expenses and noting that you hadn’t paid October phone expenses. Remember, they’re doing the closing after the period has ended, in November, so bills for the previous month or portions of it are starting to come in as other companies close their own books. In the interest of matching revenues and expenses, you want to record as much in the period realized or incurred as you can. In other cases, you might uncover potential accruals by going through the unpaid bill file and noting those for which payment is due.

Accrued Expenses

Accrued expenses are fairly common and usually result from one of these reasons:

• You are not yet obligated to pay an expense.

• You have not been billed for an expense.

• You have incurred a liability but not paid it for whatever reason.

Common accrued expenses include the following:

• Salaries

• Payroll taxes

• Income tax expense

For example, if Hobby incurred $1,000 in advertising services but did not receive the bill until the first week in November, they would still need to record the expense for October as follows:

When Hobby ultimately makes the payment in November, instead of debiting advertising expense—because they’d properly recognized the expense as a liability the month before—the company makes this entry:

A second type of accrued expense involves assets that are converted to expenses as they’re used up. Supplies, for example, often receive this treatment. If you have $600 of supplies at the beginning of the month, purchase $100, and only have $250 left at the end, you would make the following entry to adjust the balance and reflect the cost of supplies used:

Accrued Revenue

Just as you can incur expenses that aren’t yet due to be paid, you can also earn revenue for services for which your customer isn’t yet required to pay. This includes unbilled revenue and interest income.

Interest charged on notes or loans accumulates monthly but you won’t receive it until the debt is paid off. So if you have a note receivable from a customer with a face value of $1,200 and 10 percent interest payable in 3 months when the note is due, you’ll likely be required to make an adjusting entry to record interest monthly as you earn it.

First you would need to compute the monthly interest:

Amount × Interest ÷ 12 = Monthly interest earned

$1,200 × .10 = $120 ÷ 12 = $10

At the end of the first month, you would make the following adjusting entry to record earned income not received:

Two months later when the note is due, you would record the following entry:

Working with Deferrals

Deferrals are expenses or revenues incurred or earned in the current period but not recognized because they benefit future periods. Common examples are amounts prepaid in full for annual expenses like insurance or advance payments on contracts. Deferrals are set up as either assets or liabilities, with expenses and revenues recorded as they are incurred or earned, as explained in the following sections.

Deferred Expenses

Deferred expenses are sometimes called prepaid expenses because they often result from contracts for services that must be paid at the offset, but may benefit many periods in the future.

A good way to locate deferred expenses is to review any contracts or policies for which you pay an annual fee. Insurance, advertising, or rental agreements, which require payment up front, are often accounted for as deferred or prepaid expenses. Note that these amounts are classified as assets to reflect the purchase of something of value that has not yet been used. At the end of the period, the prepaid asset or deferral is credited to reflect the portion used or expired, as follows.

Note that some accountants also consider depreciation of fixed assets and amortization on intangibles and other types of assets a deferral. Basically, depreciation is a long-term, period-by-period recognition of asset usage. For the purposes of this book we cover depreciation in our chapter on fixed assets.

SEE ALSO 7.2, “Depreciation”

Deferred Revenue

Deferred revenue (also called deferred income) is revenue that’s been received but not yet earned. For this reason, it’s often called unearned revenue. Deferred revenue is recorded as a liability on the balance sheet, because the services or products for this revenue are still owed in future periods. The most common type of deferral here is a customer deposit on merchandise not yet delivered.

For example, if a company receives $1,200 in advance payment in June for a corporate training session in December, the following would need to be recorded:

The purpose of making adjusting entries is to help ensure that transactions are recorded in the correct period to properly match revenues and expenses. These entries are often for accruals and out-of-period items (inventory or services received but not yet recorded and expense items generally prorated to the period end, such as wages, interest, payroll taxes, or unbilled revenues). Other adjusting entries are deferrals—prepaid expenses or advance payments for goods or services of some kind.

10.6 The Adjusted Trial Balance

Posting Adjusting Entries

Preparing the Adjusted Trial Balance

This subchapter covers the posting of adjusting entries to the general ledger and preparation of the adjusted trial balance.

Posting Adjusting Entries

Adjusting entries are recorded first in the general journal. Then they’re posted to the general ledger and the adjusted balances are recalculated. The adjusted balances are then transferred to the adjusted trial balance, which becomes the basis for the financial statements.

THE HOBBY COMPANY

GENERAL JOURNAL

Going through the records, Hobby’s accounts discovered they had never entered the 10/31 payroll tax payment. (September taxes are due to be deposited in the next month.) So they added this journal entry as well:

Following are the general ledger accounts. The initials are posting references: CR is the cash receipts journal (cash and sales journal) and sales journal, GJ is the general journal, and CD is the cash disbursements journal.

Preparing the Adjusted Trial Balance

After you’ve made your adjusting entries, you need to compute new balances for the affected accounts, unless you have an automated system. Sometimes it’s easier to post the adjusting entries first to the trial balance, adding or subtracting to get new balances before posting to the general ledger. Either way, you need to confirm that the numbers in your adjusted trial balance add up before finalizing your general ledger.

SEE ALSO 11.3, “Preparing a Trial Balance”

To prepare the adjusted trial balance for The Hobby Company, its accountants took the adjusted account balances (bolded amounts) from the general ledger as follows:

THE HOBBY COMPANY

ADJUSTED TRIAL BALANCE

AS OF 10/31

The totals for the adjusted trial balance differ from those in the original trial balance in subChapter 10.3 because of adjusting entries. The fact that the debit and credit balances still agree means the entries have been properly recorded and summarized. An entry still could have been omitted, but if the company is careful and thorough in its bookkeeping, most adjusting entries become regular monthly occurrences, reducing the chance of error.

10.7 Generating Financial Statements

The Income Statement

The Balance Sheet

The financial statements are generated from the adjusted trial balance. In this subchapter, you learn how to put it all together and generate an interim balance sheet and income statement. You’ll also compute net income and transfer those earnings to the balance sheet as an increase in retained earnings.

The Income Statement

To prepare the income statement for the month, you can take the amounts directly from the adjusted trial balance, as The Hobby Company did:

THE HOBBY COMPANY INCOME STATEMENT

FOR THE MONTH ENDED 10/31

| Sales | $27,690 |

| Cash Discounts Allowed | $320 |

| Net Sales | $27,370 |

| Cost of Goods Sold | $4,400 |

| Gross Margin | $22,970 |

| Staff Salaries | $12,950 |

| Payroll Tax Expense | $760 |

| Automotive Expense | $250 |

| Insurance Expense | $100 |

| Utilities Expense | $720 |

| Rent Expense | $1,500 |

| Telephone Expense | $150 |

| Advertising Expense | $1,000 |

| Commissions | $200 |

| Travel and Entertainment | $900 |

| Office Supplies | $700 |

| Depreciation | $1,400 |

| Total Operating Expenses | $20,630 |

| NET INCOME | $2,340 |

The balance sheet is compiled with the asset and liability numbers. Note the amount in retained earnings (given a 0 balance in that account at the beginning) is equal to net income. Sometimes this calculation is done using a statement of retained earnings.

SEE ALSO 11.5, “Opening New Books”

Note that cash on the balance sheet is composed of petty cash and cash in the bank. This is standard format for financial statements.

Having followed The Hobby Company through its monthly closing, you should have a pretty good idea of the steps involved. To review:

1. Close accounts and summarize transactions in various journals.

2. Post from journals to the general ledger.

3. Check to be sure general ledger totals agree with supporting documentation (subledgers for accounts receivable and accounts payable).

4. Put together a trial balance with the general ledger account totals. Don’t worry if everything doesn’t add up right away, because there are still adjustments to come.

5. Make adjusting entries for items like depreciation or liabilities you’ve incurred but not yet recorded.

6. Post those entries to the trial balance to arrive at the adjusted trial balance.

7. Check to see if adjusted trial balance adds up.

8. If it balances, post the entries to the general ledger and the adjusted trial balance numbers directly into your income statement and balance sheet.

The main difference if you have a computerized system is that your final statements or “reports” will be automatically generated from the entries you make. As a side note, you should keep a separate record of the general journal entries you make and all reconciliation reports. This will come in handy in the event you’re audited or you need to review an adjustment or balance.

After that, you’re done…for this month, at any rate. Now it’s time to start over. In the next chapter, we look at the year-end procedures. That’s when you’ll officially close all your accounts and ready your books for next year.