The first three chapters introduced the reader to the accounting cycle, the Balance Sheet, and the Income Statement as well as established that accounting provides a picture of an organization but within limits and that there is no truth in accounting. The Balance Sheet provides a starting point to understand a firm’s resources and how it financed them at a point in time. The Income Statement is meant to show not only whether a firm made money (or not) but also how it generated the profit (or loss). The Income Statement is also used as the first step in forecasting a firm’s future cash flows.

This chapter illustrates the accrual method of accounting, which is what most organizations use, where revenue is recognized when goods or services are provided and expenses are matched to revenues. In other words, regardless of when cash is actually received, under the accrual method of accounting, revenue is recognized at the time of delivery. If cash is received before the goods are provided or services rendered, the cash account increases (since the firm has the cash), and a liability account is also increased (the liability reflects that the firm owes the customers goods or services). When the goods or services are then provided, the revenue is recognized and the liability is reduced. If cash is paid at the time of delivery, then cash increases and the revenue is recognized. If cash is going to be paid after delivery, then at the time of delivery, the revenue is recognized and a receivable account increases (a receivable means the customer owes the firm money). This is not as straightforward as it may seem, as there are some important complications.

When Should Revenue be Recognized?

Let us begin with revenue, the quantity of goods or services sold times the price per unit. This seems simple, and often it is. In the T-shirt vendor example in Chapter 2, $20 cash was received when the T-shirt was sold. There was no issue over the timing of the revenue because it was cash on delivery, or cash at the time of transfer. However, payments for goods or services are often received some time after delivery and, occasionally, before delivery. In Chapter 3, some T-shirts were sold with payment coming after delivery. In this case, revenue was still recognized when the goods were delivered and an asset account reflecting the amount customers owed for the T-shirts was set up.

Under the “Cash Basis” of accounting, revenue is recognized only when cash is received. This concept will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 11. For now, we will put it aside. Until Chapter 11, we are going to use what is called the “Accrual Basis” of accounting. That is, revenue will be recognized when it is earned!1 In other words, although it can occur with a cash payment, the receipt of cash does not dictate revenue recognition.

So, when is revenue recognized? New rules (both U.S. GAAP and IFRS) set up five steps:2

1. Identify a (legally enforceable) contract between the vendor and customer.

2. Identify the performance obligations (what has been promised).

3. Determine the transaction price (including any price concessions, rebates, and so on).

4. Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations.

5. Recognize the revenue as each performance obligation is satisfied.

Revenue is recognized when the product has been delivered or a portion of the service provided and when cash has been collected or the firm is reasonably assured cash will be collected.3 When revenue recognition precedes cash collection, an asset (e.g., accounts receivable) is set up. When cash collection precedes revenue recognition, a liability (e.g., deferred revenue) is set up.

There are numerous additional details beyond the scope of this book, so let us just take a look at a few examples:

How does a hairdresser recognize revenue? Like our simplified T-shirt firm earlier, services are provided (the hair is cut) and cash is paid immediately. Revenue is recognized when the hair is cut because that is when the revenue is earned.

How does an orange grove recognize revenue? The question here is one of timing: In what period should revenue be recorded? Assume there are three parts to derive revenue from an orange grove: growing the fruit, harvesting the fruit, and selling the fruit. Further assume these happen in three distinct periods: Period 1, Period 2, and Period 3, respectively. How much revenue, if any, can the firm recognize in Period 1? None. Period 2? None. Why? Because to recognize revenue you need to know the quantity and price, which the firm will not know until the oranges are sold. Because firms do not have to use a calendar year-end, it would make sense for an orange grove to pick its year-end after the selling season. What if the firm had two orange groves, one in Florida and one in Australia and the seasons did not overlap? A choice would have to be made. For one of the groves, the revenue from growing (and possibly harvesting) oranges will only be recognized in the following year. What if someone pays a flat fee for all the oranges grown in the Florida and Australia groves? Could you then recognize part of the revenue from growing? Maybe. This possibility will be discussed a bit more below.

How would a vineyard recognize revenue? Imagine a case of wine is sold for $1,200 with an additional $100 5-year storage fee. Because these are two separate transactions, the $1,200 is recognized at the time of sale and the $100 over the 5 years. But, what if the price is $1,250 for the wine and 5-year storage? In this case, each separate product or service must be valued. This can be done in many different ways. One could value the wine at $1,200 and the storage at the remaining $50. ($1,250 − $1,200). Another could prorate the wine as $1,250 × $1,200 / ($1,200 + $100) and the storage at $1,250 × $100 / ($1,200 + $100). The firm’s choice would be disclosed in the Notes to the Financial Statements.

How would a real estate developer recognize revenue? Once again, it depends. If the developer is building homes and then selling them, revenue cannot be recognized until they are sold because the price will only be known when they are sold. However, if the developer is building the home for a particular customer under a contract, then revenue can be recognized as the home is being built. Here, an assumption (with justification) has to be made as to what percentage of the work is done each period.

How should a firm that builds nuclear submarines for the government under contract recognize revenues? Can it recognize revenue as they build the submarine? Only if it has built submarines before and are reasonably sure the submarine will float (submarines do have to float).4 If this is the first submarine it has ever built, then perhaps it should wait until the submarine is built and proven to work.

Finally, how would a travel agency recognize revenue? For this example, let us go back to a travel agency in the pre-Internet era. A bricks-and-mortar travel agency where travelers would come in or call in, and an agent would book an airline flight. The agency would collect money from the traveler and give it to the airline. After the flight, the airline would pay a commission of, for instance, 5 percent to the agency. Let us assume, there are two flights booked this year for travel next year. One is for $1,000 from Boston to New York in business class. This is a full fare ticket, fully refundable or changeable. The other is for $300 from Boston to New York in coach class. This is a nonrefundable, non-changeable, use-it-or-lose-it ticket. The commission on the first ticket is $50. The commission on the second ticket is $15. Can any revenue be recognized this year or does the travel agency have to wait until next year, after the flights have taken place? When is revenue earned? At the time the work is done, when the ticket is booked, or when the flight is taken? For the first ticket, the client may cancel the flight and then no commission will be paid. The second ticket is locked in and the commission will be paid whether the customer flies or not. Regardless, all the revenue would be recognized in the year the tickets are booked as this is when the work was done. However, an allowance would be made for an estimate of the percentage of refundable tickets being canceled. This estimate would be based on past experience and industry trends.

Thus, the travel agency recognizes revenue when the ticket is sold and might set up some allowance for canceled flights. But how much revenue should be recognized? Is the revenue $1,300 (with a related inventory cost of $1,235 for a gross profit of $65) or is revenue the $65 commission? In the pre-Internet era, revenue was $65, but in the post-Internet era, it was sometimes $1,300, at least when Internet travel agencies were first set up.

What difference does it make? As can be seen from above, it has no effect on profit because the Internet travel agencies start with the ticket price and then deducts the amount the airlines keep. We end up at the same place. So, why did some Internet travel agencies do it this way? The Internet agencies were trying to raise capital and hoped investors would focus on the top line, revenue, and be fooled into thinking the agencies were generating more business and growing faster than comparable bricks-and-mortar agencies.

At the time of the brick-and-mortar travel agencies, a rule of thumb (i.e., rough estimate) for the value of a travel agency was five times revenue. In other words, if you were buying a travel agency you would pay about five times revenue, with variations to take into account location and other factors. An Internet travel agency was worth more than this because a brick-and-mortar agency could only sell to local people, whereas the Internet agency could, at least in theory, sell to anyone in the country, or even the world. Imagine that the Internet travel agency, because of its greater growth potential, was worth 10 times revenue. The estimate of the agency’s worth should have been 10 times the commission of $65. However, if an investor blindly used revenue without understanding what it entails, he might make the estimate taking 10 times $1,300. When many of these Internet travel agencies went bust, investors sued and said they had been duped, misled by the accounting. However, it was obvious what the agencies were doing. Investors were only misled if they accepted the first line as revenue without thinking about what it really meant, without looking at the numbers, and/or without having a basic idea of accounting. Although there is no doubt many of the Internet firms were trying to mislead investors, the investors appear to have been quite ready to be misled.5 Today the travel agent would be viewed as an “agent” and would be required to show only the commissions as its revenue.

Expense Recognition

How about costs? When are the costs recognized? Accountants talk about expenses, which they define as outflows from the firm, using up of assets, or incurring liabilities in the process of producing revenue or carrying out the firm’s daily operations during a period.

The concept of recording expenses in the same period as the revenues to which they relate is a fundamental principal in accounting (and referred to as the matching principal). Expenses are not defined as cash disbursements and can be recorded with, before, or after cash payments. When expense recognition precedes cash collection, a liability (e.g., accounts payable) is set up. When cash payment precedes expense recognition, an asset (e.g., prepaid expenses) is set up.

Expenses are recognized in one of two ways. First, there are those expenses that can be tied or “matched” to revenues. For example, think of the T-shirts being sold. We have a problem of how to cost the T-shirt that is sold, but the idea that when one T-shirt is sold, the cost of the shirt is matched (expensed) to the revenue makes sense. T-shirts are not expenses as the firm buys (or pays) for them from its suppliers; that is, when T-shirts become part of the firm’s resources (cash down, inventory up). The T-shirts are expenses when they are sold.

Similarly, the hair dresser could match the cost of hair spray and gel to cutting hair. The real estate developer could match the cost of materials and workers, adding them to the cost of the land, and putting it in the same period as the revenue. The travel agency could match the cost of the phones and workers to selling the tickets.

Second, those expenses that cannot be tied to revenues are recorded in the period incurred. For example, advertising is expensed in the year the advertisement runs (not when paid). Why not match the advertising to the revenue it helps produce? Because there is simply no reliable way to do it. In fact, it is impossible to even know whether an advertisement will be successful in the sense of providing any future benefits. There are many, even entertaining and award winning, advertisements that failed to increase sales.6

Note that there are two ways for management to alter accounting numbers. One is through the choice of which accounting technique, estimates or assumptions to use. The other is to change the underlying economics (in other words, decide to postpone or move up certain activities). If the firm is having a bad year and wants to increase profits, it can do so by delaying when its advertisements run. If the advertisement is delayed until next year, the cost is delayed until next year. Of course, this could adversely affect next year’s sales—but that is another issue. Likewise, in a good year, the firm could increase advertisements, thereby reducing profits in the current year with the benefit from the advertisements in the following year. Remember, there is no truth in accounting; you must understand the process in order to use accounting to gain insight into the underlying economic reality.

Standard Presentation of the Income Statement

There are many different ways to present an Income Statement. One common standard was shown in Chapter 3 and is represented below:

Not all firms have a cost of goods sold (COGS). Some service firms create a cost of services provided, but many do not, choosing instead to simply list the various individual cost categories. All the items presented are broad categories, representing the minimum required level of disclosure. More detailed information is always allowed: The question is whether the firm wants to provide it. Remember, there is a cost to provide additional information, both in its preparation and also in how it could be used by others (competitors, governments, reporters, and so on).

Many additional details, if not included in the Income Statement itself (as for the Balance Sheet), will be provided in the Notes to the Financial Statements. Let us consider revenue in more detail.

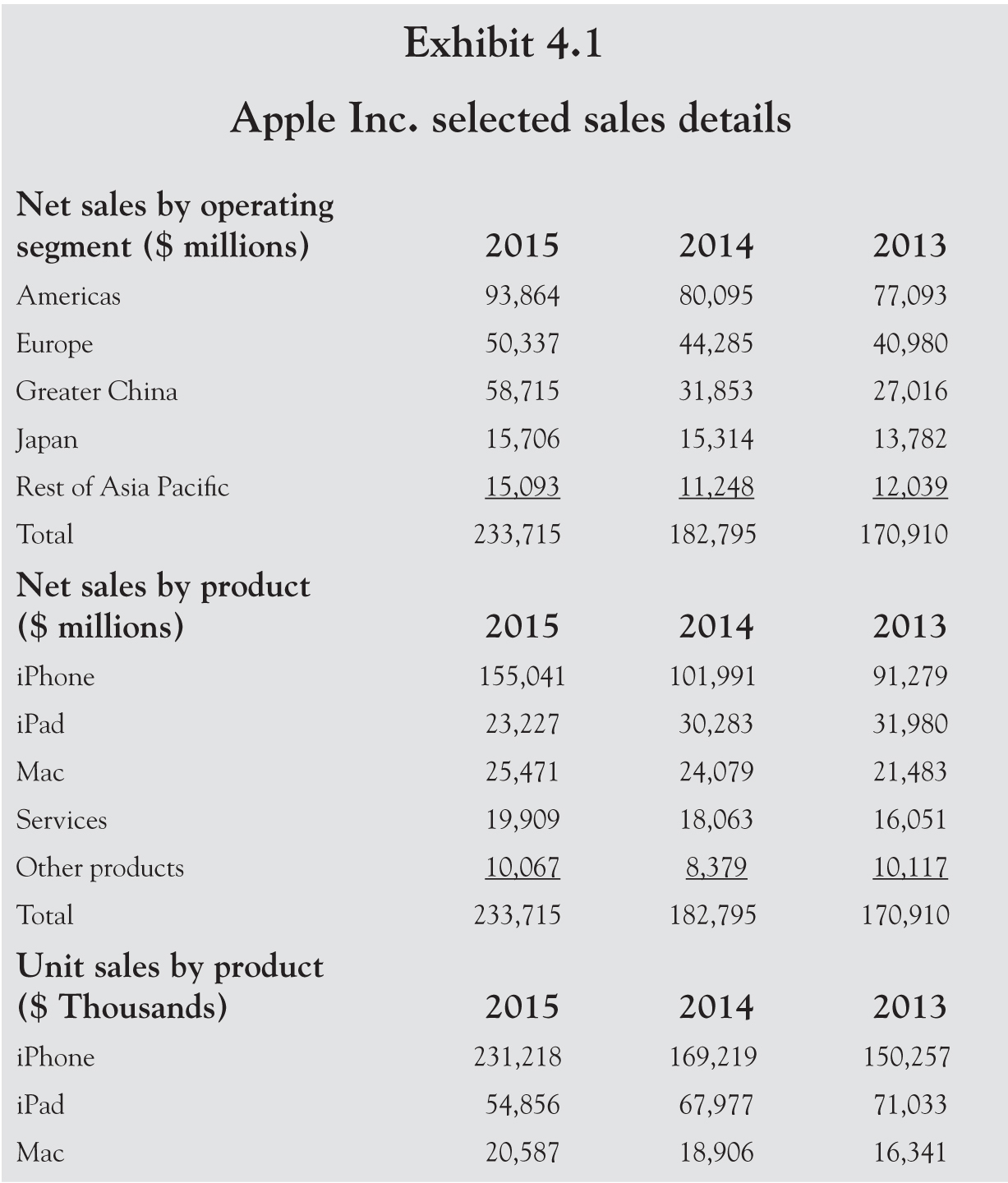

A single line for revenue would mean this amount is “net” of any returns and discounts. It may include a reduction for possible non-payments (discussed more in the next chapter). Also, depending on the nature of the firm, owners and others may want to know more about the details of the revenue. Firms are required to provide information about major classes of products as well as by geographic locations. For example, although Apple Inc.’s Income Statement reports net sales of $233,715 million for its year ending September 26, 2015, the report also discloses additional information as presented in Exhibit 4.1.

Notice that the bulk of Apple’s sales come from the Americas and from the iPhone but the highest growth is in China. The iPhone is still growing both in amount and units and at a higher rate than in the prior year. iPad sales are declining and Mac sales are somewhat flat. It is clear this data allows a reader to understand more about what Apple does and where and how it is changing over time. There is a wealth of data in an annual report beyond what is revealed in the financial statements themselves.

Revenue is not the only item for which additional information is provided. Every category of expenses also has more information, and often there are breakdowns of profit by product category and region (in effect mini-income statements). How much did Apple spend on research and development? Apple spent $8.1 billion on R&D in 2015, up from $6.0 billion in 2014 and $4.5 billion in 2013. This information is provided directly in the Income Statements. How much did Apple spend on advertising? Apple’s advertising expense was $1.8 billion in 2015, up from $1.2 billion in 2014 and $1.1 billion in 2013. This detail is found in the additional information in the Notes to the Financial Statements.

It is also worth noting how the expenses are categorized and the various subtotals presented on the Income Statement. First, there is a difference between the selling price and the direct cost (e.g., in Apple’s case, the cost to produce the product sold) and it is called gross profit. It reflects how much more a firm can sell its products for over the cost to produce or procure them. Then, the costs to operate the firm over the period are presented in a broad category called selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses. This gives a subtotal called operating profit comprised of gross profit minus SG&A. It provides the profitability of the firm before financing charges and corporate income taxes. Financing charges come next with the subtotal of profit before taxes. The expense items end with taxes and then net income or net profit (the two terms are used interchangeably and are also referred to as the “bottom line”).7

The Bottom Line

The Income Statement tries to measure a firm’s performance when revenues are earned and match expenses to the same period of revenues when possible and otherwise when incurred.

The next chapter begins our walk down the Balance Sheet looking at accounting terminology and techniques.

_________________

1There used to be an investment bank called E.F. Hutton (the firm with the same name today is a new firm which bought the name), which had a great advertisement where the announcer said, “We make our money the old-fashioned way: We earn it!” The firm had another great advertisement where it said, “When E.F. Hutton talks, people listen.” This may have nothing to do with accounting, but interesting nonetheless.

2Prior rules had many of these elements. The new rules are set to be implemented in the U.S. as of December 15, 2017 for public companies.

3Interestingly, reasonable assurance of collection is set at 50 percent under IFRS and 75 to 80 percent in the U.S.

4Submarine engineers, those who design submarines, are often in the submarine on its maiden voyage. An example of proper incentives (design the submarine well or die).

5Understand that when the Internet was established and travel agencies started doing online bookings, they said it was a new industry, a new economy, and that old accounting practices did not matter. They claimed they purchased the ticket from the airlines and sold it 2 seconds later (in fact they first obtained the order and funds, then bought the ticket and delivered it—somehow it seems to be economically the same as the brick-and-mortar process).

6One example from the late 1980s was an award winning series of advertisements for Isuzu automobiles. In the advertisements a salesman, called Joe Isuzu played by the comedian David Leisure, lied about the cars. The advertisements supposedly did increase traffic at the car dealers (and so arguably a success according to the advertising agency) but failed to increase the firm’s revenues and the cars are no longer sold in the U.S. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5IgatESU9A (viewed January 19, 2015 at 9.30 p.m. EST).

7A firm is considered in the “black” if it has made a profit or in the “red” if it has a loss. Note, the Thanksgiving Shopping Day known as Black Friday comes from the idea that it takes until sometime in late November for a retailer to make enough to cover its operating expenses for the year (and move from being in the red to being in the black).