Chapter 1

Taking Accountability

Positively the Best Decision

Frustration and exasperation were escalating among Janet's team. Their attempts to heighten accountability to boost organization performance and achieve better results had negligible impact. In fact, there was a noticeable decline in morale, enthusiasm, and engagement, with a touch of resentment and irritation to boot.

Fierce competition, shrinking margins, pressure to innovate, new government regulations, and a downturn in the economy had Squire Medical on its heels. Squire Medical was losing ground to the competition at an alarming rate.

Clayton offered, “It seems our plan to instill a stronger focus on personal accountability has had little to no affect on achieving more accountability. If anything, we have created stress, anxiety, acrimony, bitterness, and tension among the workforce.”

The board of directors viewed Janet as an up‐and‐coming leadership superstar. They had seen her perform miracles in other roles over the previous two years and had confidence in her abilities to resurrect what was once an industry leader. Complacency, with a hint of arrogance, had thrust Squire Medical into a downward spiral. The competition was intense and the stakes were high. Employee morale and engagement were at an all‐time low. Top talent was leaving in droves and those remaining had little hope of things getting better. There was a very real possibility that the plug may be pulled and assets sold off.

“I agree with Clayton. I have observed the same reactions,” Janet said. “We must create a culture that is engaged, focused, resilient, innovative, and agile.

“I believe I may have a solution to jump‐start that journey. I had an epiphany last night while attending a Miracles for Kids meeting. Within our volunteer group it is commonplace that every member is passionate, engaged, committed, and energetic when asked to get involved with a project. Members leap at the opportunity to participate, take ownership, and accountability. Everyone involved voluntarily chooses to take personal accountability to achieve what matters most. There is an indestructible level of personal ownership among all involved, and nothing will deter the members from accomplishing the desired outcomes.

“Obstacles, challenges, and barriers are viewed as trivial and as minor bumps in the road on our way to attaining our goals. Excuse‐making, finger‐pointing, blame, and inaction simply do not exist. The group's desire, focus, determination, and can‐do mindset are unrivaled. With all of the external challenges we are faced with at this time, that same passion, zeal, and energy are paramount to our future success here.”

Not quite sure what Janet meant, Clayton asked for clarification.

“What I discovered,” Janet shared, “is that too often accountability is something that is addressed after the fact. Most often after a mistake is made, when somebody drops the ball or when someone screws up. So naturally in those circumstances, accountability is viewed as punitive, historic, focused on blame, and unpleasant. Far too many people hold a negative connotation or perception of accountability because of their past experiences.

“Think about it, when do you typically hear the question being asked, ‘Who is accountable?’”

Andrew, dripping with indignation, chimed in, “Usually after somebody makes a mistake.”

“Exactly! So, what are people really hearing when that question is asked?”

“Who messed up and who is to blame!” Andrew stated with a tone of disdain.

“And when they are really hearing ‘who is to blame,’ what do people tend to come up with?”

“A litany of excuses, stories, and reasons,” Andrew declared. “People spend more time explaining why something is not their fault than they do on finding a solution.”

“And time spent playing the blame‐game is not helping anyone,” added Janet. “And as we hear more excuses being offered, as leaders we often are mistakenly compelled to ask the question ‘who is accountable’ even more. Not realizing that we are reinforcing the prevailing perception many hold of accountability being a negative experience. The more we ask the question after the fact, the more we fortify that belief. It can become a hairy monster that cannot be stopped.

“I cringe when I hear someone say the words, ‘We need to make them accountable.’ It even sounds like a punishment. We need to flip this and create positive experiences with accountability.

“How much more effective would we be as an organization if every employee voluntarily chose to take accountability rather than being pressured to be accountable? We need to engage employees on the front end—before the results are in. Think about it, when accountability is positioned up front, people have the opportunity to get excited about the ability to help while there is still time to influence the outcome.

“Our folks want to succeed in the workplace. They want to make a difference, find meaning in their work, and contribute. For the most part, people are not stupid, lazy, or defiant. People crave to find significance in their work and to feel they are part of a team doing something worthwhile. We have plenty of talented, smart people here at Squire. We need to engage and energize them to take accountability on the front end as we define and declare our desired results. Asking ‘Who is accountable?’ once the result is in does not change the result. Leadership is about getting our folks to voluntarily choose to take accountability while they can still help shape the outcome.

“With this approach we will begin to create positive, engaging, and forward‐looking experiences around accountability, which I believe will result in employees exhibiting accountable behaviors.”

Janet challenged her team to create positive experiences around accountability by engaging employees on the front end. Instead of the after‐the‐fact experience of “Who is accountable for failing to achieve the result?” the question became “Who is accountable to achieve the desired results?” The second format captivates people because they have the ability to choose the appropriate actions that will positively influence and move the team closer toward the desired result. Positioning accountability before the results are in promotes a heightened sense of control, which in turn leads to increased productivity and when people feel they have control and are productive it bolsters self‐esteem, morale, and engagement.

This new focus on enlisting employees and creating ownership, energy, and passion preceding a clearly defined “must‐achieve desired result” had an immediate and noticeable impact. Janet's team observed a distinct shift in employee enthusiasm and willingness to voluntarily take personal accountability to achieve desired results. Accountability began to be viewed as something that was positive, forward‐looking, and energizing.

Engaging, aligning, and enlisting employees up front requires leadership traits that reside inside all of us. Exemplary leaders foster high levels of personal accountability in a variety of ways on which we will elaborate throughout this book.

The cornerstone, and most essential element, to cultivating soaring levels of personal and organizational accountability is communicating top priority desired outcomes so that they are unquestionably clear in the minds of every employee. As we will reveal in later chapters, explicit and precise clarity on desired results or expectations is not as common as many believe, and the implications are severe.

A very close second element is connecting to both the head and the heart of those involved. Individuals must not only understand the logic behind the desired result, they must also recognize how it will benefit them. How will it make their job better or easier? How will it help their team? The organization? Their career? Their family? How will it make their life better or develop them? What is it that will light the fire within and get them to voluntarily choose to engage? What is in it for them? Deprived of compelling answers to these questions, many employees select compliance instead of commitment. To thrive and excel in the new world of work demands leadership create waves of enthusiasm and commitment. Obedience and compliance are ingredients commonly found in failure.

Janet discovered that when leadership changes the way accountability is experienced that employees welcome and embrace the opportunity to contribute fully. She understood that nobody relishes being told, “I am holding you accountable,” “I am going to make you accountable,” “You need to be accountable,” or being asked “Who is accountable for this?”

The leadership team at Squire Medical attributed the shift in perception around accountability as a key component of revitalizing their culture. As they described it, they transitioned from a “have‐to” to a “want‐to” culture. What the team had described as a complacent, slow‐moving, apathetic culture had transformed into one dubbed as agile, focused, innovative, and opportunistic. This change ultimately allowed Squire Medical not only to strengthen their competitive position in the market, but also to once again become the recognized leader.

Take Accountability or Blame? The Stakes Are High

Lack of accountability can lead to dire consequences. Consider the following scenario that played out in the Pacific Northwest back in 1993.

In what many described as the most infamous food‐poisoning outbreak in history at the time, 732 people became seriously ill. Four children died and 178 others were left with severe injuries, including kidney and brain damage. Panic set in throughout the Pacific Northwest. Investigators quickly discovered that people had become stricken with the E. coli virus after consuming food from Jack in the Box.

As the story was reported, Jack in the Box chose to ignore Washington state laws stating to cook hamburgers to a temperature of 155 degrees to completely kill E. coli, and instead adhered to a standard of 140 degrees.

The company's almost unforgivable response was, “No comment.” That soon led to Jack in the Box blaming their meat supplier, Vons Companies, Inc. Vons, evidently, was in no mood to take that sitting down and in a variety of ways pointed the finger of blame at the meat inspectors.

The meat inspectors were all too willing to play the blame‐game and some declared that it was the fault of the USDA due to their inadequate number of inspectors. In testimony, some went as far as to blame Congress for not providing sufficient budgets.

On and on it went. No accountability. As a result of their refusal to immediately take accountability, and with their reputation tarnished, it took Jack in the Box years to recover financially.

Jack in the Box eventually became known as an industry leader in safety and health procedures because of changes throughout the company.

Flashback to Chicago a decade earlier. Seven people died after taking capsules of Tylenol that some lunatic had laced with cyanide. Hysteria set in worldwide.

Within 48 hours Johnson & Johnson not only recalled all Tylenol products from around the globe, they incinerated $300 million (estimated in today's dollars) worth of product. This took their market share from over 35 percent to rapidly approaching zero within 48 hours.

Many people would have given Tylenol a break. After all, Tylenol could not reasonably foresee something like this taking place. Instead, Johnson & Johnson chose the approach of taking accountability and ownership.

The company determined and believed they had not done enough to protect consumers. They adopted a steadfast mindset of “what else can we do to protect and keep consumers safe?” Within weeks following the tragedy they developed tamperproof packaging, which is still used today. In fact, if you have a headache today you need to plan three days in advance so you can figure out how to open the darn package. But at the time of this tragedy, they were the innovators with the concept.

Because of their accountable “what else can we do?” mindset Tylenol recaptured over 80 percent of their market only months following their launch of the revolutionary tamperproof packaging.

Take accountability and recover in two months? Play the blame‐game and recover in years? The choice is always yours to make.

These stories clearly demonstrate the power of taking accountability. The decision as to whether you take accountability is solely yours, your team's, or your organization's.

The Magic of Taking Accountability

It is essential and vitally important to understand that nobody can make any other person accountable. One can choose to take accountability and model it in hopes that others choose to do the same. But again, you absolutely cannot make anyone accountable. In fact, you cannot make any other person do anything. The choice to take accountability is personal. You either will take accountability or you will not.

Vanquish the phrase “make them accountable,” and any variation of that, from your vocabulary. You can, however, hold others accountable. And there are best practices associated with holding others accountable. We will address those later.

Let us experience both choices.

“Good morning. I'm here to pick up the truck I rented for today,” I offered to the inattentive employee seated behind the counter. As he grunted and reluctantly peeled himself from his chair and slowly moved toward the counter, I looked at my son who mirrored my expression of concern with what we both believed we were about to experience. “You Evans?” he mumbled, never making eye contact. “Yes. I called last night to confirm my reservation and to let you know what time I would be here to pick up the truck.”

“We talked to you five minutes ago to tell you not to show up because we don't got no truck for you.” Dumbfounded and with a look of confusion, I silently glanced at my son, wondering if I had missed something. From the expression on his face, it was obvious that Nick and I were on the same page.

Nick was always observant of the experiences employees create for customers. Even as a very young child he would ask me to take him to a specific Burger King over another one that was closer to home because he liked the way the employees treated customers at the store farther down the road. Nick has a penchant for engaged, upbeat, enthusiastic, accountable employees who display a can‐do mindset. Never one to openly judge, and always with kindness, fairness, and generosity in his heart, Nick developed a habit of closely examining the experiences employees created for customers. After quickly synthesizing an interaction he would then render a decision on whether or not he would want that employee representing his future company.

Without a word, we communicated to one another, “What on earth is this guy talking about?” We had left the house fifteen minutes ago. Nobody called the house before we left and my mobile phone never rang during the drive to the rental agency.

“I believe there is a misunderstanding. What is your name?” I calmly asked the employee.

“Arnie,” he shared.

“Arnie, I did not speak with anybody from your company in the last twelve hours. My last communication was yesterday, with you I believe, to confirm the reservation and the pick‐up time. We are ten minutes early. My phone did not ring and I have no message from anyone from your company. So, are you telling me that there is no truck here for me, or just not the one I wanted?”

Arnie, with a hint of disdain, uttered, “My boss talked with you and told you we got no trucks today. We told you not to show up.”

Knowing my son was watching me closely, I took a deep breath, looked at Nick, whom I could sense was anxious to see how I would respond. I took a few seconds, attempted to synthesize the series of events, and consider that perhaps I missed something.

Reminding myself to remain calm, I offered to Arnie, “I am 99 percent certain I did not speak with anyone from your company in the last ten minutes. If I did, and was told there was no truck, I would not have shown up. Do you have any trucks at all available today? We are moving a bunch of furniture into an apartment today and we need a truck. I'll take any truck you have.”

“Do you see any trucks in the lot?” Arnie sarcastically questioned with a strong dose of indifference.

I must admit, that caught me off guard and maybe in my younger years would have set me off. However, we acquire wisdom, patience, and grace as we age. “No, Arnie. I don't see any trucks in your lot. Is there anything you or your boss can do to help me? You do have other locations in the area, don't you? Can you check with them to see if any have the same type of truck I reserved?”

“We're a franchise. I don't know what other franchise owners have.”

“Would you call a few or maybe check on your computer to see if one of the other franchises in the area might have what I need?”

Without a response, acknowledgment, or eye contact, Arnie pulled out his cell phone and walked away. Nick and I looked at each other wondering if he was checking for us, was ordering lunch, or had just given up on us. Nick took on an expression of bewilderment. He jokingly declared that someone might be playing a prank on us. I asked Nick, “Is Arnie the type of employee you would want working for you?”

“My lord no,” Nick asserted. “He seems angry that we showed up, has no interest in trying to resolve the situation, has not offered any alternatives, is taking no initiative to accommodate us, and has pretty much called you a liar. He's blamed you and his boss for creating this situation. He's pathetic and I would never use this rental agency in the future. Why on earth the owner of this company would have him interfacing with customers is perplexing.”

After watching Arnie whisper into his phone in the back office for fifteen minutes he finally strolled out and ventured back to the counter. “Got a truck for you at the Moon Township location if you want it.”

“That is about an hour away, Arnie. Is there anything closer?” Arnie looked as though someone had just asked him to solve world hunger.

“Do you want it or not? It ain't the same size truck, but you can't be choosy.”

Reluctantly submitting to Arnie, I said, “I'll take it. We cannot move without a truck.”

Arnie blurted into the phone, “He wants it,” and walked into the back office never to be seen again.

We all have had similar interactions with the Arnies of the world. At work, while shopping, while getting your car repaired, with our children, while traveling, when dining out—the list is endless. These are instances when you are dealing with someone who has no interest in helping resolve any problems, snags, or hiccups. They are drawn into the trap of blaming others, fashioning excuses, withdrawing from the predicament, or even ignoring the dilemma. Instead of focusing on what they can do to help achieve the desired outcome, they choose to take the easy way out and engage in the unwinnable blame‐game.

Apathetic, disengaged, cynical, negative, pessimistic, disinterested, lethargic, aloof, inactive, bitter, indifferent, entitled, confused, lazy, and lacking ownership are just a few of the words that commonly describe folks that renounce accountability and are sucked into the blame‐game.

Throughout the remainder of this book we will share pragmatic and memorable principles and natural laws that are proven to generate increased levels of personal, team, and organizational accountability.

The Rewards of Taking Accountability

About two miles into our drive to Moon Township, Nick suggested that we stop by, or call, a competing truck rental firm not too far from us. We pulled over into a store parking lot and made the call.

What a difference that phone call made.

From the way Chris, the sales rep, answered the phone I sensed this was a great suggestion from Nick.

Chris was filled with the desire and willingness to find a solution for us. His focus, engagement, and energy were contagious.

I had the call on speakerphone, and as Chris was doing his thing, Nick and I were giving one another a thumbs‐up. This was a guy we wanted to work with.

Chris suggested we stop by and take a look at what they had available, and that if what they had did not suit our needs, he would make sure he found us something that would.

As we approached the counter to ask for Chris, a pleasant voice wafted from behind, “Mr. Evans, I'm Chris. I am pleased to meet you. I have some trucks lined up outside. What a gorgeous day you two have for moving. Follow me and I'll show you what we have.”

“Wow! Thanks so much, Chris. I really appreciate you taking time to help us with such short notice.”

“Not a problem at all, sir. That is why I'm here. I wish we had more trucks on hand to show you, but this weekend is really busy. If none of these work for you, I can connect with other lots in the area to make sure you have a truck for your move today. Whatever it takes. I am here to please.”

As much as we wanted to work with Chris, he did not have a truck large enough for our needs.

“No problem at all,” Chris said with a smile. “Follow me into the office and let me make a few calls.” He got on the phone. “Jim, this is Chris at the McKnight site. I need you to help out my friends. Do you have a twenty‐four foot truck available today? Great, I am sending Mr. Evans and his son over. Please take good care of them.”

Nick and I climbed into the car to go pick up the truck. We looked at each other and said in what anyone observing would have thought was rigorously rehearsed choreographed synchrony, “Hire that man! That was a great experience!” What a difference in mindset, attitude, engagement, and accountability from our stop earlier in the morning.

There was nothing that was going to deter Chris from helping us. No barrier, challenge, or obstacle was going to prevent Chris from creating a very happy customer, and two customers for life. Chris chose to take accountability to achieve what mattered most to him and his company.

It was obvious that Chris was crystal clear on what mattered most to his organization. Creating exceptional client experiences is one of the company's highest desired results. That desired outcome manifested itself in the manner Chris worked with us. There was no need for his manager or owner to tell him how to behave or interact with customers. When Chris found himself in a position to influence that desired result, there was not a challenge, barrier, or obstacle that was going to prevent him from doing so. Chris could have easily used several “reasons” to offer an excuse as to why he could not help us. Instead, he maintained a can‐do mindset and focused on finding a solution. He seized complete ownership to create an optimal experience and chose to take personal accountability to ensure that outcome was realized.

Accountability Accelerator

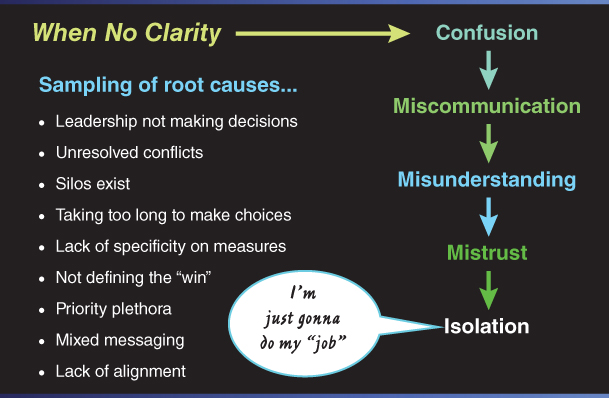

Implant, embed, and tattoo this into your brain. When your team members or employees possess only a hazy, faint, or general understanding of your must‐achieve desired results, it smothers the flames of peak performance and accountability. Worse yet, it fuels confusion, misunderstanding, miscommunication, lack of collaboration, and disenchantment.

Furthermore, when the corresponding metrics of your desired results are nebulous, or inexact, it is no better than employees not knowing them at all. Being “close” may be helpful when playing horseshoes, but not so much in business.

Your desired results (outcomes) must be memorable and internalized by every single employee involved. Equally as important, every employee must know how each of the results is being measured, what the desired metric (goal) is, and where the team or organization stands today (current metric) in relation to the desired outcome. As my former colleague and best‐selling author Dr. John Kotter regularly proclaimed, “If employees do not know where the team resides today against the desired outcome, how can they possibly make an informed decision of what actions to take in order to help move the needle in the right direction?” Think about it this way. If the players on a basketball team did not know the score of the game, did not know if they were winning or losing, or how many points they needed to ensure victory, how would that influence the decisions they make during the game? Let's take this a step further. Suppose some of the players believed they had scored enough points to win, while others felt more buckets were needed, how would that affect team play? Robbed of this information, how could the players possibly make informed decisions on how to best execute?

Many supervisors, managers, and leaders assume their employees know the top goals and objectives. Data collected over the past twenty‐five years reveals that nearly nine times out of ten, employees are not clear beyond any doubt on what is expected of them, or on their organization's most important goals and objectives. The consequences are grave.

Imagine you are a member of a highly skilled team on a clandestine mission essential to securing peace on earth. Your team is navigating the high seas as you journey to your classified outpost. Once at your desired location the mission's success is all but guaranteed. The captain of your vessel asks you to tend the helm, proceed at full speed, and hold course at 225° SW for six hours. Instead, at full speed, you maintain course at 220° SW, which is close to 225°, for six hours. What ramifications may that have on your mission's success? But you were close to doing what you were asked!

Suppose you are a musher in the Iditarod, and each of your sled dogs was running only a few degrees in different directions. What impact would that have on your desired outcome of winning the competition?

Daresay you were injured and needed an ambulance. Your friend quickly grabs her phone and dials a number “close” to the ambulance service number. How long will you be waiting for your ambulance?

Picture yourself quarterbacking a team. You identify a weakness in your opponent's defense and you call the perfect play to capitalize on it. But some of your teammates thought they heard you call a play that was “close” to the one you specified. What may happen when the ball is snapped to you?

While reading a magazine, you stumble upon what you believe is the perfect cake recipe for your upcoming family holiday event. As you follow the directions, you are pretty “close” to including all of the ingredients, but exclude the flour and sugar. What feedback might you receive from your family about your cake?

The notion of clarity and the impact it has upon high levels of accountability and performance was reinforced in my mind not long ago. I was joining my colleague Al to work with a client. When I arrived at the hotel to meet him I noticed Al rented a convertible sports car for our trip and that stirred up some internal anxiety.

Al typically drove as though he was competing to win the Indianapolis 500. He drove the same way he managed his business—full acceleration, proactive, and enthused. So I was a bit reluctant to sit shotgun for our three‐hour drive heading north on California State Route 1, which promised tight winding roadways, slow‐moving tourists, treacherous cliff‐side overhangs, few passing lanes, not to mention the frequent landslides and erosion. I prepared to white‐knuckle it and hope for the best.

We met in the lobby at 5 AM. It was still dark outside and heavy raindrops were pinging off the rooftop. As is typical near the shore, there was also a low‐hanging veil of thick fog that limited our vision severely. Not realizing it until we were several minutes into our trip, I discovered that the weather was a gift from above. The elements had come together to protect me from Al's nerve‐racking driving.

Without clear vision, direction, or sense of where he was, Al had no alternative but to move slowly, tentatively, and react to what was around him. Both of us were a bit stressed, anxious, apprehensive, nervous, and frustrated because of our circumstances.

I secretly prayed the weather would not change until we arrived at our destination.

Al's cautious driving fortified a crucial business lesson and foundational leadership practice: the importance of a well‐articulated and crystal‐clear vision of where you are going, that connects to the head and the hearts of those you are relying on to help you get there.

Exemplary leaders paint such a vivid picture of the future that employees can see themselves in it. When employees at all levels can see that future, and what is in it for them, they will voluntarily choose to take appropriate actions to help create it. It is like increasing the speed limit from 30 mph to 75 mph. The premise is simple actually. It is difficult to act inconsistently with how you see yourself in the future.

I am not talking about a long‐winded, overly verbose vision that you often may see (but not read) hanging in a corporate lobby.

What we are referring to is extreme clarity on the top two or three most meaningful results that, once accomplished, will place you, your team, or organization in a much better circumstance. Dr. Kotter referred to these desired results as “The Big Opportunities.” Another colleague of mine, Chris McChesney, co‐author of The 4 Disciplines of Execution, calls them “Wildly Important Goals.”

Selecting your two or three top priority results is not a simple task. However, it is essential to establishing heightened levels of personal and organizational accountability. At any given time, organizations have so much in play (strategies, efforts, initiatives), almost all of which are important, that asking senior leaders to select just two or three is challenging, yet absolutely vital.

There will always be more good ideas than capacity to execute on them. If every “good idea” and every goal your team or organization is targeting becomes a top priority result then you end up with no focus. If everything becomes a priority, then nothing is a priority and the result is a giant blur that chokes performance and effectiveness. The law of diminishing returns takes over and you will end up with poor to mediocre outcomes with all of your objectives. When employees are overwhelmed with a plethora of priorities, they default to a focus of being “active” rather than focusing on what matters most: your top priority results. Activity alone does not guarantee desired results will be achieved.

The key is to create unmistakable clarity on the top two or three top priority results that exist at this particular point in time that, when accomplished, will bring about the highest return. Once one or more are realized, new top priority results replace them. The top priority results are not static, but rather dynamic based upon external and internal driving forces.

Metrics are essential for focus and guidance, but your desired results should be outcomes from achieving those metrics. The selected outcomes must benefit all stakeholders and members of the team. A groundswell of momentum and waves of passion can be generated for a cause, but almost never for a metric.

Finally, the outcomes must be precise so that everyone involved is clear on what success looks like. Desired results such as “to be the industry leader,” or “become world‐class,” may be admirable and worth pursuing, and not many would argue with them either. But they do not provide the absolute clarity necessary. As an employee, these may sound great to me, but I am probably asking myself what exactly do I need to do to help us be the industry leader, or become world‐class? How close are we? How will I know when we get there? What does it look like?

When a vision, outcome, or set of desired results, is foggy, cloudy, hazy, or nebulous, employees will act and feel the way Al and I did during that trip: stressed, anxious, apprehensive, worried, nervous, unsure, and frustrated. They will be reactive, tentative, slow‐moving, and lack engagement. Those feelings and actions asphyxiate optimal performance and stifle accountability.

Imagine Al driving on that same road on a clear, sunny day. I did, and I experienced how he behaved and felt: engaged, fast‐moving, proactive, empowered, confident, assertive, poised, and with a can‐do mindset.

The same thing holds true in the business world. Clarity on must‐achieve desired results will generate those same desirable behaviors and feelings.

Close is not good enough. Unmistakable precision and accuracy are imperative.

Shine the Spotlight on the One and Only

There are times when even the best intentions inadvertently undermine the development of high levels of accountability, engagement, collaboration, and teamwork. The scenario that played out with Cameron Medical is a classic example.

At the annual sales conference, Barbara's opening comments, clear vision of the future, and the benefit it would bring to all in attendance created excitement. The conference was in full swing and the 720 salespeople attending hungered to learn more about the new products as well as the new sales plans and quotas.

Barbara was the newly appointed senior vice president of sales at Cameron Medical. She and her team were confident that the new products and technology now available to their clients had set up Cameron Medical to have perhaps their best year ever.

The sales force was adrenalized to learn that cross‐selling and collaborating with sales representatives from other regions would be instituted. This change in approach would allow them to increase individual sales and ultimately their income.

The remainder of the conference agenda included a heavy focus on product‐training, consultative‐selling skills, and developing regional sales plans.

Nancy, David, and Tony had started with Cameron Medical together seven years prior and had forged a strong friendship over the years. Although in different regions, they supported, encouraged, and helped one another over the years. As the regional teams were assembling to move into their breakout rooms, the three friends committed to meet for a drink following the regional team dinners on day three.

The next two days were a whirlwind. Intense product and sales training were followed by detailed specificity and discussion of regional sales plans. The processes and guidelines for the newly adopted strategies of cross‐selling and collaboration with salespeople in other regions were introduced and meticulously covered. Over the three days, excitement about the future possibilities swelled.

The regional vice presidents devoted the final afternoon to focusing on regional revenue goals and individual revenue assignments.

With the conference concluded, it was time for the three friends to meet up. David was the first to arrive and spotted a table in the back corner. He sat down, and was soon joined by Nancy and Tony. The three friends all appeared exhausted, but upbeat. It had been a demanding and intense, but rewarding three days.

The friends spent time catching up on family and talked about the new products and sales processes. All three agreed the new products and processes would set them up to have their best year ever.

The conversation quickly turned to the regional and individual sales contributions their vice presidents introduced during the regional breakout meetings.

“These new products are exceptional, but the increase in my revenue target is substantial and has me more than a little bit worried,” Tony admitted to his friends.

“Really?” Nancy replied. “I am feeling pretty good. My assignment is almost identical to what I had last year. Your numbers seem more aggressive than ours.”

“I am glad I do not have your number, Tony. I think I might be able to hit 100 percent of mine even though it is more than what I have done in my best years,” David said with some tentativeness in his voice.

“We were told that it will be a stretch and will require us to be more innovative and creative, and push us to think outside of the box and take risks,” Tony disclosed.

“The message we received was different,” Nancy divulged. “We were told to stick with what has worked and not to change our approach dramatically.”

“Even with the new products, growing to $1.4 billion will be tough,” Tony added.

“What do you mean $1.4 billion?” asked Nancy. “Walt told our team that $1.1 billion was the company target.”

“Wow, Maureen made us work with an organizational objective of $1.25 billion when we were developing our plans,” David confided. “It seems all of us came away from our breakouts with a different understanding of strategies and the actual organizational goal.”

As the friends talked they discovered that each regional vice president introduced different organizational goals and strategies to their regional teams.

Tony's vice president zeroed in on the “stretch” goal that the senior team felt could be achieved if the stars aligned. David's vice president used the goal the senior team felt was more reasonable. Nancy's vice president focused on the number to which the senior team had committed to the board of directors.

Annoyed, Tony claimed, “They do not even agree with what we are supposed to go after. You know what? I am just going to do my job and focus on what I have to do. Based upon what you shared with me, Nancy, the quota they assigned me is 22 percent more than what they really need from me.”

David thought aloud, “I am not sure now if my number is enough, or too much. Is it a stretch goal, must achieve, or nice to have?”

“I have made President's Club for the past six years,” Nancy remarked. “If your regions are using much higher numbers than ours, how will that impact how my performance is viewed? I am confused.”

The reality was Barbara and her regional vice presidents were quite confident that the new cutting‐edge products coupled with the new selling strategies would easily produce $1.1 billion in sales. That was a slam dunk in their minds and was the number provided to the board of directors.

In their hearts, they believed that $1.25 billion was more likely and that if everything fell into place perfectly $1.4 billion was possible.

Similar scenarios play out often in organizations of all types, and although planting a stretch goal in the minds of those you are relying upon is well intended, often it triggers negative consequences.

The lack of clarity and complete alignment around one specific desired result for Cameron Medical led to confusion, miscommunication, misunderstandings, mistrust, cynicism, apathy, stress, frustration, and isolation.

The enthusiasm, engagement, passion, and energy infused throughout the sales force was demolished by lack of alignment on the part of the senior executives.

Upon discovering the unintended consequences of their actions, the leadership team at Cameron took measures to wipe out any confusion. Though it took several weeks of focus, attention, resources, and time, the senior team at Cameron eventually mobilized the sales force to rally around one metric, $1.3 billion, and the desired behaviors for flawless execution.

Cameron Medical closed out the year with sales of $1.37 billion. Their best year ever.

An Unexpected and Illuminating Discovery

My former colleague and mentor, Tom Peters, co‐author of In Search of Excellence and many more best‐selling books, once told me, “If leaders would just get out of the way, most organizations would achieve incredible results.” His thinking was that senior leaders should spend more time visioning, strategizing, and removing obstacles, and less time directing.

George S. Patton put it this way, “Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and they will surprise you with their ingenuity.”

We could not agree more with both of them. When leadership (at any level) provides pristine clarity on top desired results, employees will astonish and amaze. Angela experienced it firsthand with her team at Lakeshore Bionics.

Angela was uneasy to the point of being distressed about her impending leave. She confided to me that she had been losing sleep dwelling on what might happen during her absence. In less than three weeks Angela would be taking leave for health‐related issues. For the four months of her sabbatical, she would be completely out of touch with anyone from Lakeshore Bionics.

“We are in the midst of implementing new systems and structures that are integral to all functions within Lakeshore Bionics. All eyes are on my team right now. Anything short of awe‐inspiring success will be viewed as disappointment.

“There is a lot riding on this. Lakeshore's recently announced growth plans, new strategic partnerships and distribution channels, my team's future, and, as selfish as this may sound, my position here. There are a lot of people counting on my team right now.”

Over eighteen years, Angela had climbed her way to a senior leadership position with Lakeshore Bionics. She described her leadership style as a bit controlling, hands‐on, directive, and with a heavy dose of managing the actions of her people. Her belief was that without her presiding over their actions it was wishful thinking on her part to expect much.

Having the opportunity to provide coaching and consulting to Angela over the prior two months, I can attest that her self‐assessment was spot‐on, and perhaps a bit light on the “command” sentiment.

It was obvious why she was feeling anxious, stressed, and apprehensive. Angela clearly did not believe her team could pull this off without her.

I encouraged Angela to spend focused time to visualize what success would look like upon her return.

Angela meticulously crafted her vision of what she was hoping her team would achieve in her absence. She spent two weeks agonizing over and detailing every one of the most crucial results that must be realized, why they were important, and how success would be measured.

A few days prior to her departure, Angela shared her vision of success with a small team of her key leaders and managers. The sparkling clarity of what was expected was unmistakable to everyone. They were aligned and committed. Yet, Angela was still distraught.

Upon her return four months later, Angela was astonished to find her team had far exceeded everything she had hoped for. Although pleased, she was puzzled. How did this happen?

As Angela talked with her team, she learned that because she was so clear in her presabbatical communication detailing her vision of success and specificity in clarifying the top desired outcomes, her people had no problem figuring out how to make them reality. In fact, she was astonished with the level of innovation, creativity, and ingenuity her team displayed during her absence.

The results she needed her team to produce were so precise, measureable, and memorable that each team member knew exactly how they contributed, no matter their role.

She discovered she did not have to waste time, energy, and effort on directing, telling, enforcing, and instructing her people. She stumbled upon a key leadership practice of creating a highly accountable culture. Angela learned that if she was precise and clear on the desired results her team must accomplish, they would figure out how to get it done. Angela found that when what is expected of them is clear, her team would voluntarily tap into their discretionary performance area to give more than what is required to achieve what matters most.

With this crucial learning as motivation, Angela's thirst to learn more was unquenchable. By internalizing, practicing, and implementing the best practices of fostering a high‐performing and accountable team, she developed into what her CEO called a model leader that he encouraged others to emulate.

Do They Know the Rules of the Game?

There is a considerable difference in the degree of engagement, commitment, passion, and personal accountability possessed by employees coming to work every day playing to win, versus those playing not to lose. This is not a subtle issue. Are your employees coming to work every day trying to keep their heads above water, or are they focused on what they can do to further the cause and help the organization move closer to what matters most? Lack of clarity breeds the mindset of playing not to lose and brings about inaction, confusion, misunderstandings, lack of alignment, anxiety, frustration, and ultimately resignation to a “just doing my job” mindset that smothers peak performance and accountability in any organization.

Deprived of the “rules of the game” and immaculate understanding of what matters most (must‐achieve desired results), the tsunami of the “day‐job” mentality takes over and employees can easily allow themselves to be sucked into the trap of busywork.

The leadership team at CVP International embraced this idea and used it to develop a culture with unsurpassed levels of accountability, ownership, collaboration, and engagement.

Debby, the senior vice president of human resources at CVP International, invited me to meet with the company's senior team of nine. CVP International partners with local and international organizations to promote social and economic change throughout the world. A highly successful firm over the years, they were looking to become even more effective. Debby shared with me that Robert, her CEO, held the topic of accountability near and dear to his heart. Her belief was that Robert would embrace the opportunity to create even higher levels of accountability among all employees.

The firm was considering several options to further develop their personnel in order to leap to the next level of performance. We were offered a window of four hours to meet with the senior leadership team, share a bit about our work, and present the case for enhancing levels of personal accountability as the most viable and beneficial option. Debby coached me in advance, sharing that these team members would be skeptical. They had already been pitched by several other firms, and were growing weary of the dog and pony shows. Debby confided that she had had to do a lot of “internal selling” simply to get this team to submit to yet another consultant's presentation. We were warned that some might choose not to show up.

Prior to our meeting with the team, Debby was able to secure a thirty‐minute telephone conversation for us to speak with Robert in order to gain a sense of what was most important to him and what he believed would propel them to the next tier of greatness.

During that conversation, we asked Robert what were the top two or three most important things his organization must achieve over the next twelve to eighteen months. This is not a simple question to answer for any CEO. There is so much that must be done in organizations, and to narrow it down to only two or three top priorities is incredibly difficult. Robert spent the next twenty‐five minutes whittling down a list of eighteen important goals down to what he believed were the three “must‐achieve no matter what” desired results.

With only a minute left in our telephone appointment, we asked one final question to Robert, “What percentage of your employees know that these are the three most important results that must be achieved?” Without hesitation, Robert confidently responded, “At least 90 percent.”

We thanked Robert for his time and told him we looked forward to meeting personally the following week.

Debby escorted us into the boardroom thirty minutes before the meeting. While we were setting up, Karen strolled in and, without introducing herself, grumbled, “How long is this going to take?”

As the next five members of the leadership team arrived, I noticed their excitement about spending four hours with me mirrored, or was substantially less, than Karen's.

Jim arrived and stated that Derek and Ken chose not to attend as their mornings had filled up and they did not have time for this. Robert was the final member to arrive. He had just finished a call with a colleague in Nigeria, and it was obvious from his demeanor that there was an issue weighing on his mind. Based on what appeared to be a common sentiment in the room—not much interest in being there—we decided to alter the planned approach.

Instead of starting with the standard introductions and niceties, along with a quick overview of our work and sharing our understanding of what they were hoping to achieve with whatever firm they chose to partner, we opted for another tactic.

“Before we start, would you open up the materials we developed for you to page six? We know your time is valuable and you all have a lot on your plate. So, let's jump right into this.

“You will see that page six is a blank lined page. Without discussing with your colleagues, write down on that page the answer to the following question, ‘If you were sitting in Robert's office and asked him what the top three must‐achieve desired results this organization must absolutely realize over the next twelve to eighteen months, how would Robert respond?’”

The facial expressions of the team were priceless. We could only imagine what they were thinking. Seven perplexed faces looked at us and then at each other, wondering what in the world they were doing here.

“Go ahead. Write them down exactly as you believe Robert would respond. We will give you five minutes to think about it.”

Robert glanced at us with what seemed to be calm assurance. You will recall that he confidently claimed to us during our telephone discussion a few days earlier that at least 90 percent of all employees, not just his senior leadership team, would be able to answer that question exactly the way he did.

As the other members sat in silent contemplation for two, three, then four minutes without writing anything in the materials, Robert's optimism turned to concern bordering on dismay.

“One more minute to finish your list, team. If you cannot come up with three, write down at least one,” we told the group.

“Now that you have your list compiled, we have two more requests for you team. Next to each result that you recorded, please write down two numbers for us. First, what percentage of your sixty‐seven hundred employees would answer the question exactly the way you did? We will give you one minute to write down that percentage.

“Secondly, how are you measuring the result? In other words, what is the metric you are using? For example, if you wrote down that we must achieve optimal customer satisfaction, how are you measuring that? What is the metric, or result, that you must achieve, and where does the organization stand against that metric today?

“Okay, so let me capture these on the whiteboard. Karen, share with me just one that you recorded on page six.”

“Well, I am not sure this is right, but I wrote down ‘employee satisfaction.’”

“Great. How many of you in the room, by show of hands, wrote down ‘employee satisfaction’?”

Two hands went up, and Robert's was not one of them.

“So, Karen, what percentage of your sixty‐seven hundred employees would have responded exactly as you did?”

Shyly and almost inaudibly, Karen said, “I wrote down 95 percent.”

“Okay, great. So let me note that on the whiteboard.

Attempting to be humorous, we suggested to Karen, “So two out of seven members of your senior team had that as a must‐achieve desired result, but you believe 95 percent of all employees would have stated that result?

“And finally, Karen, what is the metric you are using to measure that result?”

Karen whispered, “I did not get that far. I am not sure how we measure that.”

“No problem at all. Karen. Let's move on to another one. Jim, share just one that you have on your list.”

Reluctantly, Jim offered, “Healthy EBITDA.”

“Perfect. So how many of you in the room had EBITDA on page six?”

One other hand went up. Yes, of course, it was the chief financial officer.

“Okay Jim, what percentage of your sixty‐seven hundred employees would have answered exactly the way you did?”

“Well, I had written down half, but based upon what I am seeing here, I want to adjust that now.”

“For now, let's use what you have. What is the EBITDA metric that must be achieved?”

“We need to be at 12.7 or better.”

“And Jim, how many employees would know that number, or for that matter, would know what EBITDA is and how they contribute toward improving that metric?”

Humbly, Jim responded with, “Few to none.”

This exercise went on for another ten minutes. As the list of top three desired results swelled to nineteen, we could see that Robert had a moment of self‐discovery. He allowed the conversation to go on for another five minutes and then asked if he could speak with his team.

As we have discussed to this point, clearly defined desired results are foundational to cultivating high levels of accountability. See figure 1.1 for common consequences when this principle is absent, and for a partial list of some of root causes.

Figure 1.1: Lack of Clarity: Consequences and Sampling of Root Causes

“This has been eye opening for me. I need to take ownership for our lack of alignment around what is most important. I assumed you all knew. I failed you. I was certain that all of you would answer Mike's question with the same three results I identified with him on the telephone last week. I was wrong. If I did not stop this exercise that list may have ballooned to thirty or more. I would like Mike to help us come to agreement on and help us create clarity and alignment around the top three must‐achieve desired results for this firm. Then we must do what is necessary to make sure all sixty‐seven hundred of our employees know those results are what we want them to take accountability to help us achieve. Everything they do should contribute to assuring we achieve those results.”

All seven members enthusiastically agreed.

Sandra asked, “I see the value in everyone knowing the most crucial desired results, but I am not sure I get the whole ‘metric’ thing. Why is developing a metric for each one so important? Is not just knowing what is important effective enough?”

“A very valid question, Sandra,” I replied. “And the reason is rather simple. If employees do not know how we are measuring success, and where we stand today in relation to our desired state, how can they possibly show up daily and make a conscious decision about what they can do each day to take accountability to help move the needle in the right direction? It would be like opening up a board game with hundreds of pieces, but no directions detailing how to play and, more important, how to win. If I do not know how to win, how can I possibly make a purposeful decision about what action I can take to do so?

“Another bonus is that employees are at their best, and most engaged in their work, when they believe they are playing a winnable game. The highest standard to which a leader can aspire is if they are creating a winnable game for those they lead. To do so, everyone must know how we are keeping score and what the score is today.

“Suppose this huge whiteboard in the front of this room was instead a window and that we were five floors up looking over a playground basketball court. Close your eyes and create this picture in your mind. On that basketball court are a bunch of kids in the middle of a game. Assume we cannot see any scoreboard, but we know they are keeping score based on the behaviors they're displaying. Tell me what you are seeing that suggests you know they are keeping score?”

The group in the room rapidly began to shout out responses.

- “They are high‐fiving each other after a basket.”

- “I see them supporting and encouraging each other.”

- “They are playing hard, hustling, and giving it their all.”

- “They are cheering for one another.”

- “They are engaged and focused.”

- “They are talking to each other and giving advice and feedback.”

- “Everyone is contributing. Even the subs on the bench are involved and energized.”

“That was a simple exercise demonstrating how the power of keeping score ignites a variety of beneficial behaviors. Are those the types of behaviors you believe would contribute to creating a culture of accountability within CVP International?”

The message was received loud and clear.

After six months of concerted effort by Robert and his entire team to adopt and implement this key accountability principle among others, Robert called us with an update. He reported that the board of directors commended him and his team for leading the organization into heights of performance they never believed would be realized. Furthermore, they confided that they sensed a positive difference in the attitude and demeanor of the culture.

Robert went on to share a story about his recently hired new chief of party in Nigeria. After being on board for less than a week, Dikembe knocked on Robert's door and, unsolicited, offered his plan to help the firm achieve the three must‐achieve desired results that the team identified several weeks earlier.

“Evidently,” Robert exclaimed, “the constant discussion about these three results among all employees within the organization and the fact all meetings begin with a thirty‐second reminder of how that meeting will help move us closer to one of the results was eye opening for him. Dikembe divulged that the abundance of visual reminders and employee passion inspired him to proactively seek me out to pledge his alignment and dedication to doing whatever it takes to make sure we achieve them all.”

Creating a winnable game for your team or your employees is compulsory to cultivating a highly accountable organization. Employees at every level must be keenly aware of the rules of the game: the desired results; how each of those results is being measured; and where the team or organization stands today in relation to the desired metric (what must be achieved).

Heightened levels of employee engagement, commitment, creativity, perseverance, alignment, collaboration, and morale are additional bonuses resulting from this key principle.