SO, YOU’VE BEEN WORKING on increasing your outsight by following some of the suggestions in the last three chapters. What happens next? How do these efforts add up to increase your leadership capacity? To answer these questions, you have to take a closer look at how change unfolds and at some of the common misconceptions about how it happens.

People often hope that they’ll have some sort of conversion experience: a moment when it all snaps into place, after which nothing is the same again. This image comes from the archetypal stories we heard when we were growing up: the biblical story of Saul on the road to Damascus, for example. Struck down from his horse by the hand of God, he instantaneously became Paul and devoted his life to Christ thereafter. Conversion stories exist in every culture and religion. They tell about the one event that changed everything. But it’s just not the way it really works.

A much better metaphor is the story of Ulysses, on his long, wandering journey back to Ithaca—a journey with many temptations to stray. We’ll get lost along the way, lost enough to find ourselves, as Robert Frost put it.1

So it is with stepping up to play a bigger leadership role. It’s not an event; it’s a process that takes time before it pays off.

Our new actions are important, even if they sometimes seem superficial, because they provide some necessary quick wins and fresh information about what is possible. But there is rarely a straight line to the finish. Things get complicated. We get busy. Time pressure piles on. We almost always backslide or fail to stick to our commitments. Because we’re rarely very good at our new roles at first, we are loath to let go of old behaviors. What slowly starts to become more and more apparent is that our goals for ourselves are changing. That’s when reflecting on what we have been learning by doing becomes invaluable, so that the bigger changes that ensue are driven by a new clarity of self.

The Conversion of a Process Engineer

George, a manufacturing engineer, was part of a group of functional specialists, production supervisors, and engineers selected by their company to participate in a major reengineering project.2 Somewhat bored after fifteen years in the company’s operations group, George looked forward to this two-year assignment. He was eager to learn something new, to get out of the box. When he signed up, he had no idea what consequences the move would have for his career.

Working on the reengineering project profoundly changed how he thought about his organization and the purpose of his work. George acquired a big-picture view of his company and understood, for the first time, the extent to which his prior functional perspective was limited and parochial. Over time, he came to see himself as a systems thinker. He experienced a shift in how he saw his contribution, from doing great functional work to changing the organization to better serve the customer.

As these new ways of thinking took root, George found himself disconnecting more and more from his home-base work unit, where he no longer felt he really belonged, and instead seeking out opportunities to interact not just with other project team members but with a larger external community made up of others who had also been bitten by the process-engineering bug.

These new experiences and relationships led him to redefine his sense of self, his purpose in work, and his career ambitions. After the project ended, he had no desire to return to his old group. Working to change his organization was meaningful. It gave him a sense of making a difference, and he wanted to do more of it.

This change did not happen overnight but inched up on him as he worked on the project and became an ever-more-active participant in an industrywide community of process reengineers. At the start of the training that all the project members underwent, George learned the tools of business process redesign and came to understand notions like root-cause analysis and flow-charting. It was all quite abstract and theoretical, far removed from the real problems the team was being asked to solve. He was often as confused about what he was supposed to be doing as he was stimulated. To make sense of it all, George looked outside, attending conferences, hanging around with peers doing the same thing in other organizations, and reaching out to the gurus in this field. Over time, he started to understand enough about what they thought about complex systems to start coming up with his own ideas for his organization. His active participation in the world of reengineering made his new and often puzzling experiences come alive, replete with personal implications for a possible new identity as an agent for change.

Many of the leaders whose stories I have told in the preceding chapters started learning about leadership in an equally abstract way. They were exposed to classic leadership concepts, read the best sellers, hired coaches to help them improve their style, and thought hard about what they wanted and needed to change. But all that is a far cry from actually learning to do the work of leadership and coming to a deep-seated understanding of why leadership is important and personally meaningful. For that to happen, they had to live through a transition process, like George’s, that was often more challenging than they first expected.

Process, Not Outcome

Most methods for changing ask you to begin with the end in mind, the desired outcome.3 But in reality, knowing what kind of leader you want to become comes last, not first, in the stepping-up process.

George could have told you that he no longer felt challenged in his old job and that it lacked meaning for him. But no matter how much time he spent reflecting on where he wanted to go and who he wanted to become, he was never going to find the purpose he found in the reengineering work. Only his direct experiences led him to a deeper understanding of his desire for change and allowed him to construct a more attractive, concrete alternative.

Getting there wasn’t easy. During the first year of the reengineering project, George had a hard time reconciling his new role as a change agent with his earlier views about what kind of work was worth doing. For example, he learned that he actually loved managing a team—something that had been a tedious chore for him before—when the work was something he cared passionately about. But there was a price to pay for the learning: as his thinking about his organization and its problems changed, he didn’t fit in so well anymore with his old crowd.

So it is with the executives who attend my courses. After an intensive week learning about the ideas presented in the last three chapters, they go home with a personalized action plan. This plan is just meant to get them started; it is by no means a one-shot deal. More often than not, they initially commit to the low-hanging fruit, the obvious and immediate things they need to do to improve their key working relationships, extend their networks, and explore new projects. They add before they subtract, meaning that they focus mostly on what else they can do, before they start dropping things from their usual operating routines. In general, the executives tend to become very busy soon after they return to work. They get sidetracked and become frustrated with the slow pace of progress. Some of them start to give up. Those who stick to it, with help from each other via virtual group meetings and a second on-campus session, gradually start to see some evolution, but not without some hard thinking about what they must leave behind and what they will keep doing.

George and all my participants went through what I call the stepping-up process. This process is what happens in between A (where you are today) and B (where you eventually might arrive) (figure 5-1). Stepping up is a transition, and transitions are unpredictable, messy, nonlinear, and emotionally charged, for many reasons:4

• B is unknown and uncertain.

• A is no longer viable.

• There are many possible routes to B.

• B changes as we approach it.

The net result is that managing a transition is completely unlike shooting for a known outcome.5 Think about it as the difference between making a dish following a recipe and becoming a great chef. When you are trying to make something that tastes good, you pretty much achieve the desired outcome if you get the right ingredients and follow the recipe. It’s an input-output model, where the output can vary, from more to less tasty or from looking more to less like the picture in the recipe book. With practice, most people can expect to become a better cook than they were at the start.

FIGURE 5-1

Stepping up to leadership is a process of moving from A to Ba

Any process of personal change is composed of three parts: A, B, and the transition between them. A, our current state, is how we do things and who we are today. It may not be optimal, but it is familiar and comfortable because we know what to expect. We’ve been successful at A, and we know how we will be measured and evaluated when doing A. B, the future state we aspire to, is the unknown. It’s where we think we are trying to go, but that’s not always clear or well defined at the start, and it usually shifts while we are trudging through the transition. B tends to change as we change.

a. William Bridges, Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change (Philadelphia: Da Capo Lifelong Books, 2009).

When you are trying to become a great chef, the inputs also matter, but there is no direct relationship between the time and effort you put in and the outcome you get. Becoming a great chef depends on conditions that increase the likelihood that your cooking will be inventive-conditions like training under a great chef, traveling to far-off places to learn about new ingredients, a serendipitous encounter with a famous food critic, and a strong network of the best food suppliers. But none of these will guarantee that you’ll meet your goal. Success in this case depends on your becoming a different person from who you were at the start.

Stepping up to leadership is more like becoming a great chef than following a recipe. The process changes who you are in ways that you might not anticipate.

Stage 1: Disconfirmation

• Feeling the gap between where you are and where you want to be

• Increased urgency to spur first action steps

Stage 2: Simple Addition

• Adding new roles and behaviors (without subtracting old ones)

• Increased outsight; getting quick wins on low-hanging fruit

Stage 3: Complication

• Back-sliding, setbacks

• Exhaustion from making time for both old and new behaviors; obstruction as the people around you encourage your “old” self

Stage 4: Course Correction

• Frustrations that raise bigger career questions

• Time to “bring the outsight back in”: reflection on new experiences to reexamine old goals and make new ones

Stage 5: Internalization

• Changes that stick because they are motivated by your new identity and express who you have become

Although you can’t anticipate what B will actually look like as you start stepping up to a bigger leadership role, you can anticipate predictable stages in the transition. In my research and teaching, I have observed that the process typically follows a sequence of five stages. You don’t move from today’s problematic state (stage 1) to competent leadership (stage 5) in one fell swoop but rather navigate a series of steps in between (see the sidebar “Stages of Stepping Up to a Bigger Leadership Role”).

Disconfirmation

The stepping-up process almost always starts with a gap between where you are and where you want to be. That’s the spark that motivates us to take action.

Indeed, most forms of adult learning and change start with some sort of dissatisfaction or frustration generated by information or feedback that disconfirms our expectations.6 For years, psychologists using the carrot-and-stick analogy have stressed the importance of the stick, or a painful motivator, in sparking personal change—for example, the catalytic role of a negative performance appraisal or 360-degree assessment and the disconfirmation provided by a failure or personal disappointment. This frustration is the stick. When coupled with a carrot, such as strong personal ambition, a driving purpose, and a vision of our ideal selves, all the elements are in place for successful change. That’s the theory, anyway.

The problem is that the carrot-and-stick theory of self-motivation rarely works, because change is so difficult. The statistics are depressing. Some 80 percent of people who make New Year’s resolutions fall off the wagon by mid-February. Two-thirds of dieters gain back any lost weight within a year. Some people sign up for a year’s gym membership and never show up; many stop after the first month. Seventy percent of coronary bypass patients revert to their unhealthy habits within two years of their operation.7 Even in life-and-death situations, we’re often resolutely resistant to change. We may know what we need to change and agree that it is desirable, but we find it hard to do anyhow.

Likewise, most managers seek a leadership course or coaching because of a stick (e.g., negative feedback from important stakeholders like their bosses) or a carrot (e.g., a desire to get promoted or increase their impact). But the managers still make little progress, because they lack a sense of urgency to do something about the feedback (“Yes, I need to lose weight and exercise more. I’ll start next Monday”).

Let’s return to Jeff, whose team wrote “Solving problems” at the bottom of his Maslow pyramid of human needs (chapter 2). The negative performance appraisal he received for the first time ever, despite stellar results, didn’t motivate him to change. Instead, he rationalized the negative feedback by explaining to his boss why it was a good thing for the company that he, Jeff, was such a micromanager.

So what did raise Jeff’s urgency enough to put stepping up at the top of the priority list? It happened when his boss told him, “It’s time for you to choose what path you want to follow. You are a valued manager, and we are expanding rapidly in the emerging markets. There will be many more operations for you to turn around, and you will be compensated handsomely. But if you want to eventually move into the senior leadership of this firm, you need to decide now, because which way you go determines your next assignment.”

The tricky thing was that Jeff loved hands-on problem solving. But would he still love it so much after the nth time doing more or less the same? Jeff realized he would eventually get bored and find himself without other options. He concluded that the time to take action was now.

People like Jeff start to take the first steps only when they get this kind of now-or-never urgency. His urgency shot up when he realized that if he stayed too long in the same kind of role, he would never get a shot at the top. Other people experience an urgency infusion from meeting people who are clearly making a bigger impact or from one of the biggest urgency raisers of all—losing their job or an opportunity they really wanted.

Simple Addition

It’s hard to stop doing something that is rewarding when there isn’t a better, more interesting way to spend your time. That’s why the best place to start is often by doing what I call simple addition: doing some new things that allow you to practice new behaviors and push you outside the box of your usual work routines and networks.

As described earlier in the book, Jacob never got around to delegating more and micromanaging less until he found something more interesting to do: working on his company’s acquisition strategy. The problem, however, was that he was finding it hard to stick to his personal goal of spending two hours of uninterrupted time in his office, because every time he shut the door, one of his direct reports came knocking. They came knocking because he hadn’t yet performed a second crucial operation: subtraction. He was still doing too much of the work himself.

As we saw, Jacob also resolved to patch up his relationship with his sales director and to get to know his peers across the lines better so that they were more likely to consider his ideas. After all, there was no use spending two hours a day thinking strategically if no one paid attention to his well-thought-out ideas. To increase his team’s autonomy, Jacob also started investing more time coaching his subordinates and scheduling more meetings, to improve communication and detect problems earlier (and thus avoid the constant firefighting). He found himself busier than he had ever been.

Like Jacob, high achievers who start working on new skills typically find themselves with more things to do than there is time for. It’s tough to squeeze new roles and activities into an already-full schedule, and our early efforts inevitably take time before they pay off enough that we willingly shed time-consuming tasks and responsibilities that no longer merit so much of our attention.8 In the interim, our work continues to cue our old routines, and we find it hard to stick to the new plan. Only when the new leadership activity has become rewarding enough to be sustaining do people like Jacob stop investing large chunks of their time on the older, more ingrained operating habits.

Complication

Jacob had entered what I call the complication stage. He found himself reverting to his comfortable “driver” style, and his team concluded that his efforts to behave differently were not genuine.

Personal change, like organizational change, is rarely the linear, upward progression we naively hope it to be. (We assume that it’s just a matter of getting hit by the right trigger or catalyst—or brick to the head.) Changing ourselves is also rarely the way theory tells us it should be—the familiar S curve with a slow takeoff followed by rapid progress past the tipping point. In fact, things usually get worse before they get better. Personal change is more like a line of peaks and valleys, false starts, new beginnings, rocky progress (figure 5-2).

We’ve already discussed one reason for the circuitous path to real change: your own capacity to stick with it through the harder times. A second reason is that many of the people around you don’t think you can or will sustain the changes-and that implicit expectation affects you much more than you’d think. Toward the end of my courses, when my students are feeling the most energized and motivated to go back to work and make some real changes, I show them a single-frame cartoon. In the background, a bespectacled man is bursting through an office door, arms raised in victory. He is wearing a superhero’s cape and tights with “MANAGER’S EMPOWERMENT SEMINAR” emblazoned across his chest. Meanwhile in the foreground, a single worker, hunched over her desk and clutching her head, looks away and grimaces. Everyone laughs, but they get it.

FIGURE 5-2

Models of personal change

The problem, as the cartoon illustrates, is that your newly inspired self inevitably returns to a team or an organization that does not understand or appreciate the new thinking to which you have been exposed. Your bosses, teams, close work colleagues, and even your friends and family haven’t had the conversion experience. Worse, they will be suspicious of any new and unpredictable behavior on your part. Often, their attitude is, “If we just ignore him, he will get over it.” Consciously or not, they remain invested in your old self. The pressures of the old situation conspire against your will to change, and soon, it’s back to business as usual.

One financial services executive, Olav, fell exactly into this trap. He took a one-month-long general management course, as he needed a break from his longtime career with a firm he had helped to found. “I was burned out, unenthusiastic,” he said. “I thought of taking the course as hitting the refresh button.” During the training, Olav got excited by what he learned about leading change: “When I came back, I was pumped up to create change in my firm.” But after a month away, his to-do list was long and everyone was eager for him to take care of what hadn’t gotten done while he was away. The changes he looked forward to implementing failed to materialize.

Making progress through the complication stage often requires a new assignment, because staying in the old situation keeps you vulnerable to all the old expectations of the people who have come to know (and love) you in the old role. A new assignment is exactly what got Jeff through the transition. After he stepped up in the old job, his boss rewarded him with a stretch assignment: heading a larger unit that served a much larger market. This organization was way too big and complex to be run in Jeff’s familiar, hands-on way, and although it needed improvement, it was not a turnaround. It forced him to do a very different job, to grow his network, and to change his sense of himself: it motivated him to take the change to the next level.

Course Correction

The frustration of the complication stage eventually led Olav to revisit his goals for himself. His training course had opened up a whole new world. He picked up exciting ideas about how to shake up his stodgy company. He met peers who shared similar experiences, and he was exposed to career paths he had never even envisioned. Before the program, he had simply wanted to refresh himself. But his ambitions grew as a result of everything he had experienced. An image of himself as someone who could more confidently take on a strategic role began to blossom. Unfortunately, neither his cofounder nor his subordinates were prepared for the metamorphosis; his fledgling efforts were stymied at each turn by a firm that hadn’t grown as he had. On reflection, Olav realized he had outgrown the junior role his cofounder still expected him to play. Olav course-corrected his goals and ended up leaving to take an entrepreneurial path, starting his own firm.

Note that Olav’s goals didn’t guide his stepping-up process; they emerged from the process. He had not been clear about his objectives, simply because he himself did not previously know what they were. What good would it have done him to spend a lot of time up front getting clear on what his objectives were?9

How we set our objectives and how those goals help us perform are topics that have fascinated psychologists for decades.10 Unfortunately, much advice to people in the midst of a transition comes down to mechanistic prescriptions, like setting specific, measurable, ambitious goals that presume a static world and leave little room for iteration. Most theories say, for example, that the most effective goals are concrete and measurable. But many times, our concrete goals don’t take into account the likelihood that the new behaviors required to meet our goals will end up changing our objectives.

When the executives I teach come back to campus after months away working on the action commitments they made during the training, they typically return armed with different goals and concerns than those they had stated at the outset. After addressing the most problematic aspects of their 360-degree feedback, their other most urgent problems, and their personal goals that were the easiest to achieve, the executives start thinking about the medium to longer term. They also start thinking more about their own agendas, not just what other people want them to do.

This is when they begin to bring the outsight back in—to reflect, revise, and course-correct their goals for their careers and for themselves. In Olav’s case, his frustration (and anger) ultimately led him to a deeper realization: he had outgrown his organization; in any case, it wasn’t going to let him keep growing. This realization took a while to hit home because he was still operating under an older set of career and personal goals, ones that concerned his role in his current company.

While the changes we make at first begin with small steps and incremental moves, at some point it becomes important to reexamine the goals, priorities, and ambitions that have been driving us and to ask whether they are still relevant for the future. As we gain experience, we are better placed to judge our relative success or failure in meeting the goals we have previously set for ourselves and, more importantly, to step back to appraise whether our goals have changed.

Internalization

Psychologists use the term internalization to refer to the process by which superficial changes, tentative experiments, and fuzzy career goals become your own. I call it bringing the outsight back in. When you internalize a change, it becomes grounded—real and tangible—in your direct experience and is rooted in new self definitions. The outsights become insights.

Internalization is the necessary step that allows people to move from what they know and do to who they are.11 There is a big difference between doing what you think you are supposed to do and doing things because of who you are and what you firmly believe. For example, a manager might know that she has to deviate from her PowerPoint bullets to deliver a more emotional speech to badly demoralized employees and actually do a decent job of it. But if she has internalized the value of inspiring and connecting to people in a more personal way, she will deliver a more powerful speech because it is congruent with her values and her sense of the value she wants to bring: it’s who she is. Likewise, it was one thing when I first told the story about being advised to “mark my territory” in class; it’s quite another to appropriate it to make a point I now firmly believe.

FIGURE 5-3

The transition process

Figure 5-3 summarizes the five stages of the transition process. It’s a circle because, interestingly, becoming the kind of person you aspire to be is the most powerful motivator of all. This motivation will raise your urgency to keep going and seek out even more opportunities to lead. And the cycle begins again.

Stepping Up or Stepping Out?

In some instances, stepping up results in a move to a new assignment, as it did for Jeff. Alternatively, a person might stay in the same job but approach her work in a completely new and different way, as Sophie did. Other times, the journey leads us to a major career change, as it did for Olav.

How do we recognize when we have outgrown our jobs or organizations? When is it time to go? Many people who step up to leadership eventually get to this question, which is not always easy to answer. As we saw earlier, leadership experience increases clarity about who we are and want to become and creates urgency for more opportunities to develop our leadership further. When these motives remain unfulfilled by our organizations, we start to look elsewhere.

Many of the executives in this book ultimately asked themselves, “Should I stay or should I go?” For example, during her stint running alternative energy at BP, Vivienne Cox realized that her leadership style and philosophy had been evolving away from what she saw as the dominant model at her company. Her experiments with doing it more her way, within the context of a new venture within her organization, made her want to play around with her self-conception further. But the limits to what was possible within BP were hard and clear, and she ran up against them. So, she continued the work in a different role at another organization.

When a person reaches his midcareer, the stay-or-go question is often laden with psychological meaning, as it was for Robert (chapter 2), who ultimately realized that his motive for leaving wasn’t just getting a bigger job. It was part of a growing-up process that required breaking free from his dysfunctional relationship with a father-figure boss and mentor whom Robert had never dared to oppose.

Having had a certain measure of career success, Robert, Vivienne, and many of the other managers whom I interviewed for this book came to ask themselves whether they wanted more of the same or something different, and whether their current organization allowed them sufficient rein to express the leader they had become. For anyone facing these kinds of questions, research on adult development suggests that making sense of the deeper outsights gained in the stepping-up process requires a more personal kind of reflection.12

A Life of Transitions

Psychologist Daniel Levinson is credited with having popularized the ideas of the seven-year itch and the midlife crisis. His research found that change tends to come in cycles and that lives evolve in alternating periods of stability and transition.

Stability periods, he said, lasted on average about seven years. That doesn’t mean that we don’t make any changes during these periods, and certainly, we make more frequent changes today than when Levinson first conducted his studies in the 1970s.13 But the changes we make during these periods are more incremental. They don’t upset everything. During a relatively stable period (relative because, of course, our lives are constantly evolving), we make a few key decisions regarding our work and family life, and these become the priorities around which we organize our lives and fit in (or leave out) everything else. Our job is to execute and implement “the plan.” But after a while, we realize that something is not working in what we have set up. Maybe we’ve changed, maybe the situation has changed, and sometimes it’s both.

During transition periods, which are shorter and typically last about three years, people become more open to reconsidering not just what they are doing but the premises and goals on which their actions are based. They consider, and often make, more radical changes. Our job now is to probe the choices we have made, explore alternative possibilities, and plant the seeds from which might grow a new period of relative stability.

If you find yourself in a transitional period, it’s probably because you’ve started doing some different things that give you a glimpse of new possibilities. That’s when you need to step back and ask yourself questions like these:a

• What am I really getting from and giving to my work, colleagues, professional community—and myself?

• Do I know what I truly want for myself and others? How can I start finding out?

• What are my central values, and how are they reflected in my work?

• What are my greatest talents, and how am I using (or wasting) them?

• What have I done with my early ambitions, and what do I want of them now?

• Can I live my work life in a way that leaves enough room for other important facets of my life?

• How satisfactory is my present state and trajectory, and what changes can I make to provide a better basis for the future?

a. Daniel J. Levinson, The Seasons of a Man’s Life (New York: Knopf, 1978), 192.

According to Levinson’s research, the most potentially turbulent transition period of all happens sometime around age forty (many have argued, however, that today, fifty is the new forty because we are living and staying active longer).14 At midlife or midcareer (however we may define it), people gain more urgency for change, seeing it as a now-or-never proposition. They feel that they still have enough time to play out another chapter of their lives or careers but not enough to waste time in an outdated one. They want to give rein to facets of themselves they have not had time to express. They also have enough experience with earlier choices to be able to evaluate them. And stuff happens that changes our priorities as well as the opportunities available. That’s when we start asking the big questions (see the sidebar “The Big Questions”).

One of the biggest challenges of a midcareer transition is knowing what to change and what to keep. Sometimes the temptation is to change everything at once. But major, external moves like changing jobs and careers won’t always take us to a better place. James Marcia, a student of the great psychologist Erik Erickson, argued that what is more important instead is to grow by questioning where we are today, actively entertaining alternatives, and eventually committing to making changes, whether they are external changes like job moves or more internal changes like changing the way we think about what we do and why.15

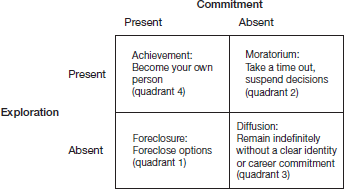

His model of the different “identity states” that can characterize a person at any given moment is summarized in figure 5-4. Each of the four states describes where a person falls along two continua: exploration on the one hand and commitment to concrete choices on the other. When we commit to a career path, job, or company without ever exploring whether it is the right choice for us, we foreclose on options that might be more rewarding (quadrant 1). If we don’t yet commit but continue to explore, such as taking a sabbatical, going back to school for a spell, or even job hopping in search of ourselves, we are in what Marcia calls the moratorium stage (quadrant 2). But when we question endlessly without truly exploring anything in depth and never commit to an old or a new career path, we also forgo the possibility of mastery and maturity. Marcia calls this stage identity diffusion (quadrant 3), because we are figuratively all over the place. As one person I interviewed put it, “There are two types of people. Some are always jumping. Some never jump—they settle down too easily and get stuck.” To be a growing adult means making commitments that are informed by prior exploration and questioning (quadrant 4); this stage is identity achievement, an apt term because it only comes to us through a process of becoming ourselves.

The problem with what Marcia calls foreclosure is that we often don’t realize that’s what we are doing. No one chooses to foreclose options explicitly. But that’s what happens when we let the years elapse without asking ourselves the big questions. Too much certainty is as much a problem as too much doubt, not necessarily because we might be in the wrong job but because we might unwittingly remain the victim of other people’s values and expectations. Sometimes we so fully internalize what other people think is right for us that we don’t ever become what Harvard psychologist Robert Kegan calls “self-authoring.”16 Earlier in our lives and careers, Kegan explains, we make decisions according to social expectations about what constitutes a good job, a good employer, and a loyal employee. The task at midcareer is to understand those hidden assumptions so that we can break free from our “ought selves”-what important people in our lives think we ought to be-to become our own person. The sidebar “Self-Assessment: Are You in a Career-Building Period or in a Career-Transitioning Period?” can help you understand where you are in a transition.

FIGURE 5-4

The four states of exploration and commitment in managing transitions

Source: Adapted from J. E. Marcia, “Development and Validation of Ego Identity Status,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 3 (1966): 551–558.

| YES | NO | |

| 1. I have been in the same job, career path, or organization for at least seven years. | ______ | ______ |

| 2. I find myself feeling a bit restless professionally. | ______ | ______ |

| 3. On balance, my job is more draining than energizing. | ______ | ______ |

| 4. I resent not having more time for my outside interests or family. | ______ | ______ |

| 5. My family configuration is changing in ways that free me up to explore different options; for example, my kids have left for college or my partner’s career situation has changed. | ______ | ______ |

| 6. I envy (or admire) the people around me who have made major professional changes. | ______ | ______ |

| 7. My work has lost some of its meaning for me. | ______ | ______ |

| 8. I find that my career ambitions are changing. | ______ | ______ |

| 9. Recent personal events (e.g., a health scare, the death of a loved one, the birth of a child, marriage, or divorce) have led me to reappraise what I really want. | ______ | ______ |

| 10. I don’t jump out of bed in the morning excited about the upcoming day. | ______ | ______ |

Assess whether you are in a transitional period by totaling the number of “yes” responses:

| 6–10 | You are likely to be deep into a career-transitioning period. Make time to reflect not only on your new experiences but also on whether your life goals and priorities need rethinking. |

| 3–5 | You may be entering a career-transitioning period. Work to increase outsight via new activities and relationships. |

| 2 or below | You are more likely to be in a career-building period. |

The process of bringing the outsight back in might lead you to make significant external changes in your career and lifestyle; alternatively, you may entertain doubts but decide to remain where you are, making changes that can be significant even if they are not so visible to the outside world. The stepping-up process outlined in this chapter describes the path to getting there.

CHAPTER 5 SUMMARY

✓ Stepping up to play a bigger leadership role is not an event; it’s a process that takes time before it pays off. It is a transition built from small changes.

✓ Most methods for changing ask you to begin with the end in mind-the desired outcome. But in reality, knowing what kind of leader you want to become comes last, not first, in the stepping-up process.

✓ The transition process is rarely linear; difficulties and complications will inevitably arise and often follow a predictable sequence of five stages:

1. Disconfirmation

2. Simple addition

3. Complication

4. Course correction

5. Internalization

✓ Getting unstuck when problems inevitably arise requires that you reflect and integrate the new learning-to bring the outsight back in-so that the ensuing changes are driven by a new self-image that is based on your direct experience.

✓ Making major, external moves like changing jobs and careers, however, does not necessarily take you to a better place. More important is to grow by questioning where you are today, actively entertaining alternatives, and eventually committing to making changes. The changes can be external, like job moves, or more internal, like changing the way you think about what you do and why.

✓ Breaking free from your “ought self”—what important people in your life think you ought to be—is at the heart of the transition process.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.