“I’M LIKE THE FIRE PATROL,” says Jacob, a thirty-five-year-old production manager for a midsized European food manufacturer. “I run from one corner to the other to fix things, just to keep producing.”1 To step up to a bigger leadership role in his organization, Jacob knows he needs to get out from under all the operational details that are keeping him from thinking about important strategic issues his unit faces. He should be focused on issues such as how best to continue to expand the business, how to increase cross-enterprise collaboration, and how to anticipate the fast-changing market. His solution? He tries to set aside two hours of uninterrupted thinking time every day. As you might expect, this tactic isn’t working.

Perhaps you, like Jacob, are feeling the frustration of having too much on your plate and not enough time to reflect on how your business is changing and how to become a better leader. It’s all too easy to fall hostage to the urgent over the important. But you face an even bigger challenge in stepping up to play a leadership role: you can only learn what you need to know about your job and about yourself by doing it—not by just thinking about it.

Most traditional leadership training or coaching aims to change the way you think, asking you to reflect on who you are and who you’d like to become. Indeed, introspection and self-reflection have become the holy grail of leadership development. Increase your self awareness first. Know who you are. Define your leadership purpose and authentic self, and these insights will guide your leadership journey. There is an entire leadership cottage industry based on this idea, with thousands of books, programs, and courses designed to help you find your leadership style, be an authentic leader, and play from your leadership strengths while working on your weaknesses.2

If you’ve tried these sorts of methods, then you know just how limited they are. They can greatly help you identify your current strengths and leadership style. But as we’ll see, your current way of thinking about your job and yourself is exactly what’s keeping you from stepping up. You’ll need to change your mind-set, and there’s only one way to do that: by acting differently.

Aristotle observed that people become virtuous by acting virtuous: if you do good, you’ll be good.3 His insight has been confirmed in a wealth of social psychology research showing that people change their minds by first changing their behavior.4 Simply put, change happens from the outside in, not from the inside out (figure 1-1). As management guru Richard Pascale puts it, “Adults are more likely to act their way into a new way of thinking than to think their way into a new way of acting.”5

So it is with leadership. Research on how adults learn shows that the logical sequence—think, then act—is actually reversed in personal change processes such as those involved in becoming a better leader. Paradoxically, we only increase our self-knowledge in the process of making changes.6 We try something new and then observe the results—how it feels to us, how others around us react—and only later reflect on and perhaps internalize what our experience taught us. In other words, we act like a leader and then think like a leader (thus the title of the book).

FIGURE 1-1

Becoming a leader: the traditional sequence (think, then act) versus the way it really works (act, then think)

How Leaders Really Become Leaders

Throughout my entire career as a researcher, an author, an educator, and an adviser, I have examined how people navigate important transitions at work. I have written numerous Harvard Business Review articles on leadership and career transitions (along with Working Identity, a book on the same topic). Interestingly, most of what I’ve learned about transitions goes against conventional wisdom.

The fallacy of changing from the inside out persists because of the way leadership is traditionally studied. Researchers all too often identify high-performing leaders, innovative leaders, or authentic leaders and then set out to study who these leaders are or what they do. Inevitably, the researchers discover that effective leaders are highly self-aware, purpose-driven, and authentic. But with little insight on how the leaders became that way, the research falls short of providing realistic guidance for our own personal journeys.

My research focuses instead on the development of a leader’s identity—how people come to see and define themselves as leaders.7 I have found that people become leaders by doing leadership work. Doing leadership work sparks two important, interrelated processes, one external and one internal. The external process is about developing a reputation for leadership potential or competency; it can dramatically change how we see ourselves. The internal process concerns the evolution of our own internal motivations and self-definition; it doesn’t happen in a vacuum but rather in our relationships with others.

When we act like a leader by proposing new ideas, making contributions outside our area of expertise, or connecting people and resources to a worthwhile goal (to cite just a few examples), people see us behaving as leaders and confirm as much. The social recognition and the reputation that develop over time with repeated demonstrations of leadership create conditions for what psychologists call internalizing a leadership identity—coming to see oneself as a leader and seizing more and more opportunities to behave accordingly. As a person’s capacity for leadership grows, so too does the likelihood of receiving endorsement from all corners of the organization by, for example, being given a bigger job. And the cycle continues.

This cycle of acting like a leader and then thinking like a leader—of change from the outside in—creates what I call outsight.

The Outsight Principle

For Jacob and many of the other people whose stories form the basis for this book, deep-seated ways of thinking keep us from making—or sticking to—the behavioral adjustments necessary for leadership. How we think—what we notice, believe to be the truth, prioritize, and value—directly affects what we do. In fact, inside-out thinking can actually impede change.

Our mind-sets are very difficult to change because changing requires experience in what we are least apt to do. Without the benefit of an outside-in approach to change, our self-conceptions and therefore our habitual patterns of thought and action are rigidly fenced in by the past. No one pigeonholes us better than we ourselves do. The paradox of change is that the only way to alter the way we think is by doing the very things our habitual thinking keeps us from doing.

This outsight principle is the core idea of this book. The principle holds that the only way to think like a leader is to first act: to plunge yourself into new projects and activities, interact with very different kinds of people, and experiment with unfamiliar ways of getting things done. Those freshly challenging experiences and their outcomes will transform the habitual actions and thoughts that currently define your limits. In times of transition and uncertainty, thinking and introspection should follow action and experimentation—not vice versa. New experiences not only change how you think—your perspective on what is important and worth doing—but also change who you become. They help you let go of old sources of self-esteem, old goals, and old habits, not just because the old ways no longer fit the situation at hand but because you have discovered new purposes and more relevant and valuable things to do.

Outsight, much more than reflection, lets you reshape your image of what you can do and what is worth doing. Who you are as a leader is not the starting point on your development journey, but rather the outcome of learning about yourself. This knowledge can only come about when you do new things and work with new and different people. You don’t unearth your true self; it emerges from what you do.

But we get stuck when we try to approach change the other way around, from the inside out. Contrary to popular opinion, too much introspection anchors us in the past and amplifies our blinders, shielding us from discovering our leadership potential and leaving us unprepared for fundamental shifts in the situations around us (table 1-1). This is akin to looking for the lost watch under the proverbial streetlamp when the answers to new problems demand greater outsight—the fresh, external perspective we get when we do different things. The great social psychologist Karl Weick put it very succinctly: “How can I know who I am until I see what I do?”8

TABLE 1-1

The difference between insight and outsight

| Insight | Outsight |

| • Internal knowledge | • External knowledge |

| • Past experience | • New experience |

| • Thinking | • Acting |

Lost in Transition

To help put this idea of outsight into perspective, let’s return to Jacob, the production manager of a food manufacturer. After a private investor bought out his company, Jacob’s first priority was to guide one of his operations through a major upgrade of the manufacturing process. But with the constant firefighting and cross-functional conflicts at the factories, he had little time to think about important strategic issues like how to best continue expanding the business.

Jacob attributed his thus-far stellar results to his hands-on and demanding style. But after a devastating 360-degree feedback report, he became painfully aware that his direct reports were tired of his constant micromanagement (and bad temper) and that his boss expected him to collaborate more, and fight less, with his peers in the other disciplines, and that he was often the last to know about the future initiatives his company was considering.

Although Jacob’s job title had not changed since the buyout, what was now expected of him had changed by quite a bit. Jacob had come into the role with an established track record of turning around factories, one at a time. Now he was managing two, and the second plant was not only twice as large as any he had ever managed, but also in a different location from the first. And although he had enjoyed a strong intracompany network and staff groups with whom to toss around new ideas and keep abreast of new developments, he now found himself on his own. A distant boss and few peers in his geographic region meant he had no one with whom to exchange ideas about increasing cost efficiencies and modernizing the plants.

Despite the scathing evaluation from his team, an escalating fight with his counterpart in sales, and being obviously out of the loop at leadership team meetings, Jacob just worked harder doing more of the same. He was proud of his rigor and hands-on approach to factory management.

Jacob’s predicaments are typical. He was tired of putting out fires and having to approve and follow up on nearly every move his people made, and he knew that they wanted more space. He wanted instead to concentrate on the more strategic issues facing him, but it seemed that every time he sat down to think, he was interrupted by a new problem the team wanted him to solve. Jacob attributed their passivity to the top-down culture instilled by his predecessor, but failed to see that he himself was not stepping up to a do-it-yourself leadership transition.

The Do-It-Yourself Transition: Why Outsight Is More Important Than Ever

A promotion or new job assignment used to mean that the time had come to adjust or even reinvent your leadership. Today more than ever, major transitions do not come neatly labeled with a new job title or formal move. Subtle (and not-so-subtle) shifts in your business environments create new—but not always clearly articulated—expectations for what and how you deliver. This kind of ambiguity about the timing of the transition was the case for Jacob. Figure 1-2, prepared from a 2013 survey of my executive program alumni, shows how managerial jobs have changed between 2011 and 2013.

FIGURE 1-2

How managers’ jobs are changing, from 2011 to 2013

The percentage of respondents saying these are the responsibilities that have changed over the past two years

Source: Author’s survey of 173 INSEAD executive program alumni, conducted in October 2013.

The changes in managerial responsibilities are not trivial and require commensurate adjustment. Yet among the people who reported major changes in what was expected of them, only 47 percent had been promoted in the two years preceding the survey. The rest were nevertheless expected to step up to a significantly bigger leadership role while still sitting in the same jobs and holding the same titles, like Jacob. This need to step up to leadership with little specific outside recognition or guidance is what I call the do-it-yourself transition.

No matter how long you have been doing your current job and how far you might be from a next formal role or assignment, this do-it-yourself environment means that today, more than ever, what made you successful so far can easily keep you from succeeding in the future. The pace of change is ever faster, and agility is at a premium. Most people understand the importance of agility: in the same survey of executive program alumni, fully 79 percent agreed that “what got you here won’t get you there.”9 But people still find it hard to reinvent themselves, because what they are being asked to do clashes with how they think about their jobs and how they think about themselves.

The more your current situation tilts toward a do-it-yourself environment, the more outsight you need to make the transition (see the sidebar “Self-Assessment: Is Your Work Environment Telling You It’s Time to Change?” at the end of this chapter). If you don’t create new opportunities within the confines of your “day job,” they may never come your way.

How This Book Evolved

This book describes what outsight is and how to obtain it and use it to step up to a bigger leadership role, no matter what you’re doing today. The ideas in this book are the same ones in The Leadership Transition, an executive education course that I developed and taught for over ten years at INSEAD. Nearly five hundred participants from over thirty countries have gone through the program. I have read their sponsors’ evaluations, analyzed the participants’ 360-degree feedback, listened to their challenges, and watched the evolution of their personal goals, from the time the leaders first arrive to when they return for a second round three months later. From the earliest days of teaching The Leadership Transition, my INSEAD colleagues and I have used the outsight ideas to guide participants successfully through their transitions.

Both this book and my course are based on my decades of research on work transitions. The notion of outsight that is central here originated in some of my earlier work on how professionals stepped up from project management to client advisory services and on how people change careers.10 In both areas of study, I found that introspection didn’t help people figure out how to do a completely different job or move into a completely different career—or even figure out if they wanted to. This finding also held for people stepping up to leadership.

Many of the ideas about how to increase outsight also came out of my original research. For example, my PhD thesis on why some people’s ideas for innovative products and processes meet fertile ground, and why other ideas don’t, led to some leadership-networking concepts discussed here.11

As my leadership course evolved, I zoomed in on two cohorts for more in-depth interviews. A research assistant and I interviewed the thirty participants in one year’s program—all the participants from different companies and industries. We also wrote case studies about a few participants; the case studies are the basis for some of the stories you will read in this book. Years later, we interviewed a second cohort, a group of forty high-potential managers striving to move up to the next level in a large consumer-goods company; we hoped to flesh out the pitfalls and successful strategies involved in stepping up.

I also took advantage of many opportunities to validate or adapt my theories about what it takes to step up to bigger leadership roles. I shared my findings with dozens of companies and many alumni and HR and talent management groups. I spoke with headhunters about the alarmingly high failure rates of the executives they placed, and I met with leadership development specialists trying to put in place better practices in their companies. I adapted my course accordingly, in light of all these inputs. In 2013, I conducted a survey of my alumni to learn more about how their jobs were changing, what leadership competencies the leaders thought were necessary, what was helping them to step up, and what they still found hard. The result is this book about outsight and how we can increase our outsight to become better leaders.

FIGURE 1-3

The outsight principle: becoming a leader, from the outside in

How Outsight Works

The stepping-up guidelines detailed in this book are based on three critical sources of outsight. First is the kind of work you do. Second, new roles and activities put you in contact with new and different people who see the world differently than you do. Rethinking yourself comes last in this framework, because you can only do so productively when you are challenged by new situations and informed by new inputs. Developing outsight is not a one-shot deal but an iterative process of testing old assumptions and experimenting with new possibilities.

So the best place to begin is by making changes in how you do your job, what kinds of relationships you form, and how you do what you do (figure 1-3). These outsight sources form a tripod, working together to define and shape your identity as a leader (or to hold you back). Ignore any one of the legs, and the foundation is not stable. That’s why no amount of self-reflection can create change without important changes to what you do and with whom you do it.

How, specifically, do these outsight principles work? Let’s examine each of the three essential sources of leadership outsight, using Jacob as an example, to see some concrete actions.

Redefine Your Job

As Jacob’s intuition told him, stepping up to leadership implies, first and foremost, shifting how he spends his time. But two hours of quiet time in his office isn’t the right investment. In fact, most of the required shifts in what Jacob does must take him off the factory floor, where his office is located.

In today’s fast-paced business world, value is created much more collaboratively, outside the lines of self-contained groups and organizational boundaries.12 People who can not only spot but also mobilize others around trends in a rapidly changing environment reap the greatest rewards—recognition, impact, and mobility. To be successful, Jacob must first redefine his job, shifting from a focus on improving current factory operations to understanding the firm’s new environment and creating a shared strategic vision among his functional peers so that his manufacturing operation is better aligned with organizational-level priorities. The work involved in understanding how his industry is shifting, how his organization creates value, how value creation may change in the future, and how he can influence the people who are critical to creating value—whether or not they are inside his group or firm—is very different from the many functional activities that currently occupy his time.

As mentioned earlier, Jacob wanted to concentrate on the capital investments his company would require over the next two years, but he had no time for this sort of introspection. He complained about “the fire patrol” of overseeing his people and his production facilities. But he knew that his boss expected him to craft a strategy based on a view of the overall business as opposed to the perspective of a super–factory director and to actively work to bring on board the relevant stakeholders.

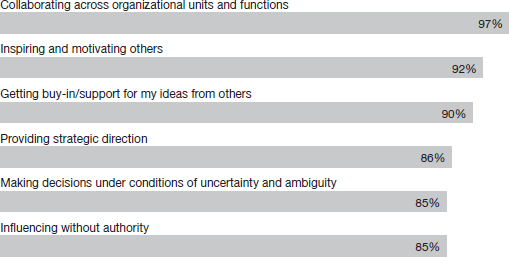

Jacob’s focus so far had been successful and is typical of many managers at his stage of development. Early in our careers, we accomplish things within the confines of our specialty groups. We make the transition to managing the work of others, usually within our own functional or technical areas, typically in domains in which we are expert. But as we start to move into bigger leadership roles, the picture starts to change radically.13 When I asked the participants in my survey what competencies were most critical to their leadership effectiveness, they listed competencies that required a great deal of outsight focus (figure 1-4). But not surprisingly, 57 percent of the same managers also responded “somewhat or very true” to the statement “I let the routine and operational aspects of my work consume too much of my time.”

As psychologists remind us, knowing what we should be doing and actually doing it are two very different things.14 Shifting from driving results ourselves to providing strategic direction for others is no easy task. It requires collaborating across organizational units or functions instead of mostly working within the confines of our own groups or functions. It means refocusing our attention from having good technical ideas to getting buy-in for those ideas from an extended and diverse set of stakeholders. Ultimately, we are moving away from implementing directives that are handed down from above to making decisions under conditions of uncertainty or ambiguity about how the business will evolve. All of these shifts depend on us to change our priorities and points of view about what matters most. Only then do we actually start changing the way we allocate our time. The only place to begin is by moving away from the comfort and urgency of the old daily routine.

FIGURE 1-4

The most important leadership competencies

The percentage of respondents saying these leadership abilities are important or extremely important to being effective today

Source: Author’s survey of 173 INSEAD executive program alumni, conducted in October 2013.

Chapter 2 further develops the idea of redefining your job as the first step to increasing your outsight. It argues that the place to start stepping up to leadership is changing the scope of your “day job” away from the technical and operational demands that currently consume you in favor of more strategic concerns. Prioritizing activities that make you more attuned to your environment outside your group and firm, grabbing opportunities to work on projects outside your main area of expertise, expanding your professional contributions from the outside in, and maintaining slack in a relentless daily schedule will give you the outsight you need to think more like a leader.

Network Across and Out

It’s hard to develop strategic foresight on the factory floor. As we saw, to step up to leadership, Jacob needed to see the big picture, to spend less time “on the dance floor” and more time “up on the balcony,” as Harvard professor Ronald Heifetz describes it.15 Jacob would thus also have to change the web of relationships within which he operates to spend more time outside.

Ultimately, he needed to understand that the most valuable role he could play would be a bridge or linchpin between the production environment and the rest of the organization. Like many successful managers, he had grown accustomed to getting things done through a reliable and extensive set of mostly internal working relationships; these had paid off handsomely over the years. For Jacob, these operational networks were very useful for exchanging job-related information, solving problems within his functional role, and finding good people to staff teams. But they stopped short of preparing him for the future, because they did not reach outside the walls of his current mind-set.

When challenged to think beyond their functional specialty and to concern themselves with strategic issues to support the overall business, many managers do not immediately grasp that these are also relational—and not just analytical—tasks. Nor do they easily understand that exchanges and interactions with a diverse array of current and potential stakeholders are not distractions from real work, but are actually at the heart of the managers’ new roles.

But how do we come to think more cross-functionally and strategically? Where do we get the insight and confidence we need to make important decisions under conditions of uncertainty? As experienced leaders understand, lateral and vertical relationships with other functional and business unit managers—all people outside our immediate control—are a critical lifeline for figuring out how our contributions fit into the overall picture and how to sell our ideas, learn about relevant trends, and compete for resources. Only in relation to people doing these things do we come to understand and value what they do and why. These outsights help us to figure out what our own focus should be—and therefore, which tasks we can delegate, which ones we can ignore and, which ones deserve our personal attention.

Our networks are critical for our leadership development for another reason, too. When it comes to learning how to do new things, we also need advice, feedback, and coaching from people who have been there and can help us grow, learn, and advance. We need people to recognize our efforts, to encourage and guide early steps, and to model the way. It helps a lot to have some points of reference when we are not sure where we are going.

But the sad state of affairs, however, is that most of the executives I teach have networks composed of contacts primarily within their functions, units, and organizations—networks that help them do today’s (or yesterday’s) job but fail to help them step up to leadership. In Jacob’s case, he was on his own to figure it out. Similarly, many of the people who come to my courses also report that they are not getting the help they need from inside their departments and companies. My survey shows that the biggest sources of help were external. The managers’ bosses or predecessors came in fourth place as bases of support, putting the managers squarely in a classic do-it-yourself transition (figure 1-5).

In fact, only 10 percent of the participants answered “very true” when asked if they had a mentor or sponsor who looked out for their career. Stepping up to leadership, therefore, means not only learning to do different things and to think differently about what needs to be done but also learning in different, more self-guided, peer-driven, and external ways. In brief, it means actively creating a network from which you can learn as much as, if not more than, you can from your boss.

FIGURE 1-5

Expand your network out and across: help for becoming a more effective leader

Looking outside: the percentage of respondents rating each of the following helpful to extremely helpful in becoming a more effective leader

Source: Author’s survey of 173 INSEAD executive program alumni, conducted in October 2013.

Chapter 3 shows how much good leadership depends on having the right network of professional relationships. It discusses how to branch out beyond the strong and comforting ties of friends and colleagues to connect to people who can help you see your work and yourself in a different light. Even if you don’t yet value networking activities, are swamped with more immediate job demands, and suspect anyhow that networking is mostly self-serving manipulation, a few simple steps will demonstrate why you can’t afford not to build connective advantage.

Be More Playful with Your Self

To really change what he does and the network he relies on to do it, Jacob would have to play around a bit with his own ideas about himself. Both the scope of his job and the nature of his working relationships were a product of his self-concept—his likes and dislikes, strengths and weaknesses, stylistic preferences and comfort zone. Now he needed to shift from his familiar, hands-on, and directive leadership style to a style in which he would delegate more of the day-to-day work to his team and begin to collaborate more extensively with the other divisions. The improved empowerment and communication he had been trying so hard to implement didn’t stick, because they clashed with his sense of authentic self.

To an even greater extent than doing a different job and establishing a different network of work relationships, people in transition to bigger leadership roles must reinvent their own identities. They must transform how they see themselves, how others see them, and what work values and personal goals drive their actions.

While the personal transformation typically involves a shift in leadership style, it is much more than that. Consider the following: 50 percent of the managers I surveyed responded “somewhat or very true” to the statement “My leadership style sometimes gets in the way of my success.” In Jacob’s case, he admitted that if results lagged behind his expectations, he would often leap into the situation without allowing the team members the time and space to arrive at their own solution. When managers like Jacob are asked to consider what is holding them back from broadening their stylistic repertory, many almost invariably reveal an unflinching results orientation and commitment to delivering at all costs. This orientation not only has made them successful but also constitutes the core of their professional identities. The managers want to change, but the change is not who they truly are.

For example, among the competencies rated as most critical for effective leaders, my survey respondents listed “motivating and inspiring” as the second-most important. Jacob also listed the same, although he was not rated very highly by his team on this capacity. Motivation and inspiration, however, aren’t tools you can select out of a toolbox by, say, increasing your communication to keep people better informed. Instead, the capacity to motivate and inspire depends much more on your ability to infuse the work with meaning and purpose for everyone involved.16 When this capability doesn’t come naturally, you tend to see it as an exercise in manipulation. Likewise, coming to grips with the political realities of organizational life and managing them effectively and authentically are among the biggest hurdles of transitioning to a bigger leadership role.17 Although many of the aspiring leaders whom I teach cite the ability to influence without authority as a critical competence, many leaders are not as effective as they might be at it, because they view the exercise of influence as playing politics.

Things like stretching outside your stylistic comfort zone and reconciling yourself to the inherently political nature of organizational life, in turn, require a more playful approach than what you might adopt if you see it as “working on yourself.” When you’re playing with various self-concepts, you favor exploration, withholding commitment until you know more about where you are going. You focus less on achievement than on learning. If it doesn’t work for you, then you try something else instead.

Chapter 4 explains why trying to adapt to many of the challenges involved in greater leadership roles can make you feel like an impostor. No one wants to lose herself in the process of change, yet the only way to start thinking like a leader is to act like one, even when it feels inauthentic at first. This chapter shows how you can stop straitjacketing your identity in the guise of authenticity. The out-sight you gain from trying to be someone you’re not (yet) helps you more than any introspection about the leader you might become.

Stepping Up

Stepping up to play a bigger leadership role is not an event or an outcome. It’s a process that you need to understand to make it pay off.

| YES | NO | |

| 1. My industry has changed a lot over the past few years. | ______ | ______ |

| 2. My company’s top leadership has changed. | ______ | ______ |

| 3. My company has grown or reduced significantly in size recently. | ______ | ______ |

| 4. We are undergoing a major change effort. | ______ | ______ |

| 5. We have new competitors we did not have a few years ago. | ______ | ______ |

| 6. Technology is changing how we do business. | ______ | ______ |

| 7. I need to interact with more stakeholders to do my job. | ______ | ______ |

| 8. I have been in the same job for more than two years. | ______ | ______ |

| 9. I have been sent for leadership training. | ______ | ______ |

| 10. Our business is becoming much more international. | ______ | ______ |

Total Score

Assess whether your work environment is telling you it’s time to change by totaling the number of “yes” responses:

| 8–10 | Your environment is changing dramatically, and your leadership must change accordingly. |

| 4–7 | Your environment is changing in important ways, and with it, the expectations for you to step up to leadership are growing. |

| 3 or below | Your environment is experiencing moderate shifts; prepare for changing expectations of you. |

Between realizing that you’re in a do-it-yourself transition and actually experiencing the accumulated benefits of the new out-sights you’re getting lies a stepping-up process that is less linear than what you would expect. The transition involved is rarely the upward and onward progression you’d like; nor does it tend to unfold according to any theoretical logic. The transition moves forward and then falls backward repeatedly, but at some point, if you learn enough along the way, the transition sustains its momentum.

Most of the leadership books written for people who want to get from A to B simply tell you what B is: what great leadership looks like. Or, they tell you how to identify a good B for you and then how to measure the gap between your current A and that B. Then they give you a few simple tactics that supposedly will help you fill the gap. Few of the books guide you through the complications in between.

The complex step-up process is the subject of chapter 5. Describing the predictable sequence of stages that change the way you think about A and B, the chapter prepares you for the complications that will inevitably arise in between. It helps you get unstuck when problems arise (they will) and builds a foundation that sustains more enduring changes. You’ve succeeded in stepping up when the bigger changes that ensue are driven by a new clarity of self that is informed by your direct leadership experience.

![]()

How much are you like Jacob? How much has the way you work evolved over the past couple of years? How about your network—is it growing and extending beyond the usual suspects? And how much are you willing to challenge the way you see yourself? The action and thinking shifts that all of us, like Jacob, must make as we step up to bigger leadership roles are the subject of the next four chapters.

Jack Welch famously said, “When the rate of change outside exceeds the rate of change inside, the end is in sight.”18 Before you read ahead, take a moment to evaluate the extent to which changes in your work environment signal that the time has come for a do-it-yourself transition (see the sidebar “Self-Assessment: Is Your Work Environment Telling You It’s Time to Change?”).

CHAPTER 1 SUMMARY

✓ To step up to leadership, you have to learn to think like a leader.

✓ The way you think is a product of your past experience.

✓ The only way to change how you think, therefore, is to do different things.

✓ Doing things—rather than simply thinking about them—will increase your outsight on what leadership is all about.

✓ Outsight comes from a “tripod” of sources: new ways of doing your work (your job), new relationships (your network), and new ways of connecting to and engaging people (yourself).

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.