WHEN I ASK THE MANAGERS and other professionals who attend my classes how many of them are involved in creating change of some sort in their organizations, close to 90 percent raise their hands. When I ask the same managers about the results of their efforts, most admit that the results leave much to be desired. Inertia, resistance, habitual routines, and entrenched cultures slow the participants’ progress at every turn.

There is no doubt that the capacity to lead change is at the top of the list of leadership competencies. But in today’s fast-paced and resource-constrained environment, many of us are delivering 100 percent on the current demands of our jobs. Not only is there little time to think about the current business, but we cannot easily carve out the time to sense new trends coming down the line or to develop ourselves further for a future move. That’s why a majority of the mangers I surveyed said that routine and operational aspects of their work consume too much of their time.

One of my executive MBA students recently told me, “I know that I have to carve out more time to think strategically about my company’s business, but all my peers are executing to the hilt and I don’t want to fall behind.” Prompted to describe her predicament, she was at a loss to explain what she should be doing increasing your outsight by redefining your job instead. She just knew that she was limiting her contribution by merely responding to the many client requests getting pushed down to her level without stopping to consider how the pieces fell together or how to prioritize directives coming down the line. But she didn’t dare stop, because everyone around her was continuing to push on the operational front.

What does it mean to take a more strategic approach to our jobs? Boiled down to its essence, strategy entails knowing what to do among the many things competing for our attention, how to get it done, and why. Unfortunately, the way most of us do our work leaves little room for this kind of strategic thinking.

Consider your typical work routine. For most of the managers I meet, the day usually begins with a quick check of the most urgent emails, followed by a round of long, routine, and often boring meetings and conference calls with the team or key customers. Incessant travel and dealing with the chronic talent shortages and high turnover of the emerging markets or the retrenchment of the more mature ones adds an unprecedented burden of overwork. With a multiplication of corporate initiatives, compliance procedures, and urgent requests from all corners, the responsibilities pile on. At the end of a long day, the inbox is full again and the requested reports (or budgets or analyses) have yet to be finished. There is little time to think about why you do what you do, about the meaning and purpose of your work beyond the immediate deliverables. It’s no wonder routine crowds out strategy.

This chapter is about how to apply the outsight principle to adopt a more strategic approach to your work, whether you are taking charge in a new role or simply stepping up to leadership within the confines of your current position. It will show you how to reallocate your time to prioritize unfamiliar and nonroutine activities that will increase your capacity to act more strategically through a wider view of your business, your group’s place in the larger organization, and your work’s contribution to outcomes that matter (figure 2-1).

FIGURE 2-1

Increasing your outsight by redefining your job

Doing the Wrong Things Well

Sophie, a rising star in her firm’s supply-chain operation, was stupefied to learn that a radical reorganization of the procurement function was being discussed without her input. Rewarded to date for steady annual improvements, she had consistently delivered on her key performance indicators but failed to notice the competitive shifts in her firm’s markets. These shifts were making her firm’s historical approach to purchasing and warehousing expensive and ineffective. Nor was she aware of the resulting internal shuffle for resources and power at the higher levels of her company and the extent to which her higher-ups were now pressured to increase cost efficiencies. She was the last to hear about any new imperatives, let alone anticipate them.

Although she had built a loyal, high-performing team, Sophie had few relationships outside her group and even fewer at her boss’s level. Putting in long hours to continuously improve her operation left her little time to keep up with the latest trends in supply-chain management. Her function area, the supply chain, was also in the midst of a radical transformation as manufacturers expanded internationally, pursued strategic sourcing, and built more collaborative and sustainable relationships with suppliers. Lacking outsight on innovations in her field, she was blindsided by a proposal from her counterpart in manufacturing.

Her first reaction was defensive. The supply chain was her purview, and her results were impeccable; if a strategic review was in order, she should be the one in charge, she argued. But without the benefit of the broader, cross-functional, and external perspective that her boss expected of someone three years into the job, her ideas were discounted as parochial. Lacking greater strategic insight, she could not form a sellable plan for the future—one that took into account new industry realities and the shifting priorities of her firm.

At first, Sophie thought hard about quitting and moving to a “less political” firm. After all, she was only trying to do the right thing. It seemed to her that the only way to be heard was to spend time schmoozing with senior management instead of getting the job done. Only after some patient coaching from a senior manager did she start to venture outside her cocoon and talk to a broader set of people inside and outside the company. Reluctantly, she conducted a study to learn what other companies were doing. Next, she brought in a consultant to help her narrow down her options. This project brought her in contact with a range of people at her boss’s level, across the different divisions of the company. She learned about how they saw the business evolving. Eventually, after a 180-degree turn in how she defined and went about her job, she came to see that a very different supply-chain strategy was indeed required, one that made irrelevant most of what she had built.

Sophie learned the hard way that she was very efficient—at the wrong thing. She was not much different from many successful managers who continue to devote the bulk of their time to doing what they have learned too well. They define their jobs narrowly, in terms of their own areas of expertise, and confine their activities to where they have historically contributed the most value and consistent results. At first, this narrow role is what’s expected of them. But over time, expectations shift. To avoid the kind of competency trap Sophie fell into, you need to understand how once-useful mind-sets and operating habits can persist long after they have outlived their usefulness.

Avoid the Competency Trap

We all like to do what we already do well. Sports coaches tell us that amateur golfers spend too much of their time practicing their best swings, at the expense of the aspects of their game that need more work. Likewise, every year, we see the downfall of yet another company that was once the undisputed leader in a given product, service, or technology, but that missed the boat when a new, disruptive technology came along.1

That is precisely what happens when we let the operational “day job” crowd out our engagement in more strategic, higher-value-added activities. Like athletes and companies, managers and professionals overinvest in their strengths under the false assumption that what produced their past successes will necessarily lead to future wins. Eventually we become trapped in well-honed routines that no longer correspond to the requirements of a new environment.

Consider Jeff, a general manager for a beverage company subsidiary. A star salesman before he became a star sales manager, Jeff also succeeded as country head in two successive assignments, both positions in which the general manager’s job was actually a mega–sales manager position, and the business required a turnaround. His third assignment, in Indonesia, looked like more of the same, albeit at a larger scale and scope. After two years of implementing what everyone regarded as a successful turnaround strategy, Jeff was sure that his results had put him squarely in the running for senior management. But no new assignment was in sight, and a poor performance review hinted that Jeff’s bosses were starting to expect something else from him.

What was going on? Although Jeff was still delivering results as before, his bosses now wanted to know more about his capacity to lead at a higher level. All the indicators left them doubtful.

For starters, it was becoming obvious that he was on the verge of losing his head of sales and marketing. Rajiv was the only person in the operation with the technological expertise required to develop and implement the company’s new digital strategy in its local market. The extroverted and relationship-oriented Jeff had little patience with the IT and data issues that consumed his highly analytical Indian marketing chief, and the cultural differences between the two men only made their communication harder. Rajiv saw his job as aligning new marketing technologies with business goals, serving as a liaison to the centralized brand groups, evaluating and choosing technology providers, and helping craft new digital business models. Jeff wanted Rajiv to devote more time to managing relationships with the group’s distributors, the cornerstone of his strategy, and felt that Rajiv was neglecting his sales responsibilities. Every time they spoke, the conversation ended in a stalemate. Unbeknownst to him, Jeff’s managers worried that he was ill equipped to manage the diverse teams he would encounter in a higher-level assignment.

Jeff’s bosses were also displeased by the way he routinely ignored corporate initiatives and failed to keep the brand and staff functions informed and involved. Earlier, Jeff’s superiors had shown more patience with his lone-ranger tactics, because the turnarounds he had been asked to pull off called for speedy and decisive action. Now his bosses were curious to see if he could adapt to changing circumstances. The Indonesian operation was in the black again, thanks to Jeff’s tried-and-true approach. E-commerce initiatives were forcing leaders to grapple with some of the responsibilities that typically fell to marketing, such as how to deliver brand messages directly via the web. But Jeff continued to define the local strategy pretty much in terms of sales, neglecting the views and priorities of his peers in the company’s corporate staff.

Not surprisingly, the leadership bench in Indonesia remained underdeveloped. Jeff routinely stifled his team’s development by intervening in the details of their work, “adding too much value,” as leadership coach Marshall Goldsmith jokingly describes this sort of micromanagement.2 Jeff was starting to itch for a new challenge, but unfortunately, he had made himself so indispensable that there was no one ready to succeed him. Let’s analyze how Jeff had gotten himself into a competency trap.

We enjoy what we do well, so we do more of it and get still better at it. The more we do something, the more expert we become at it and the more we enjoy doing it. Such a feedback loop motivates us to get even more experience. The mastery we feel is like a drug, deepening both our enjoyment and our sense of self-efficacy.3 It also biases us to believe that the things we do well are the most valuable and important, justifying the time we devote to them. As one unusually frank, high-potential manager told me, it can be hard to do otherwise: “I annoy a lot of people by not being sympathetic to their priorities. It’s feedback I’ve had throughout my career: you work on things you like and think are important. It is a problem. It can seem disrespectful. Do I want to work on it? I should but probably never will.”

It was much the same for Jeff, who found himself solving other people’s problems over and over again. When his managers failed to build relationships with key clients, Jeff stepped in. When accounts were not settled, he rushed to the rescue. Instead of working through his team, he was working for them. “I can’t sit still if I see a problem that could have real financial consequences,” Jeff would say. “I need to hammer away at it until things get done correctly.”

His direct reports teased him for this: they made him a “Jeff’s hierarchy of needs” diagram, based on Abraham Maslow’s famous pyramid (figure 2-2).4 Below the bottom rung (physiological needs), they had drawn another, titled “Solving problems.” Jeff liked the diagram; it reflected how he liked to see himself. When he was solving problems, his most basic needs were met: he felt valuable, decisive, competent, and in control of the ultimate outcome.

FIGURE 2-2

Jeff’s “hierarchy of needs” pyramid

When we allocate more time to what we do best, we devote less time to learning other things that are also important. The problem isn’t just what we are doing; it’s what we’re neglecting to do (and not learning to do) instead. Because experience and competence work together in a virtuous (or vicious) cycle, when that competence is in demand, as it often is, it invites further utilization. So some leadership muscles get very strong while others remain underdeveloped.

Jeff, like many successful managers, was focusing too much on the details—particularly in his domain of functional expertise—and micromanaging his teams so that he single-handedly drove performance. What was he failing to do? A lot. He wasn’t strategizing for the more stable medium term made possible by his successful turnaround. He wasn’t taking into account the views and priorities of his corporate support functions. He wasn’t having difficult conversations with key members of his team or coaching them through the issues that got them in over their heads. He wasn’t keeping his far-off boss adequately informed. It’s not that Jeff was unable to do any of these things; he just didn’t know how to do them in a way that didn’t seem like a huge time sink.

Over time, it gets more costly to invest in learning to do new things. The better we are at something, the higher the opportunity cost of spending time doing something else. The returns from exploiting what we already do well are more certain and closer in time and space than the returns from exploring potential new areas in which we will necessarily feel weak at first.5 This self-reinforcing property of learning makes people sustain their current focus in the short term.

A team of Harvard Business School researchers set out to discover how bosses spend their time.a They asked the administrative assistants of the chief executives of ninety-four Italian firms to record their activities for a week. What did the executives spend the most time on? You guessed it: they spent 60 percent of their time in meetings.

Years earlier, a classic study compared managers who were rated highly effective by their own teams with managers who were successful in moving up to higher positions.b The biggest difference between the two groups of managers was how they spent their time. The effective managers spent most of their time working with their direct reports inside their teams. The successful managers spent much more time on networking activities with peers in other units and higher-ups throughout the organization.

Even if you don’t have the luxury of an assistant, in this age of apps, it’s easy to track what you spend your time on, at work and at home. Start by simply observing what you do in a typical week. You might, for example, track how much time you spend alone in your office and inside versus outside your department. You can use tools like these to keep tabs on your time:c

Toggl and ATracker: These apps let you track anything you do; you simply tap on your phone to start or stop each activity. ATracker’s reports show how much time you are spending on routine tasks and formal activities like meetings.

TIME Planner: This app combines scheduling and time tracking features. You can schedule some reflection time at 1 p.m., for example, then be reminded to do it, and then register whether you’ve actually done it.

My Minutes: This app helps you meet your time management goals. If you resolve to spend at most forty-five minutes on a presentation, for example, the app tells you when you’re out of time and when you’ve hit your goal.

a. Oriana Bandiera, Luigi Guiso, Andrea Prat, and Raffaella Sadun, “What Do CEOs Do?” working paper 11-081 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2011).

b. Fred Luthans, “Successful vs. Effective Real Managers,” Academy of Management Executive 2, no. 2 (1988): 127–132.

c. Adapted from Laura Vanderkam, “10 Time-Tracking Apps That Will Make You More Productive in 2014,” Fast Company, January 6, 2014, www.fastcompany.com/3024249/10-time-tracking-apps-that-will-make-you-moreproductive-in-2014.

Perversely, the trap is sprung precisely because we are delivering on our results. When we are reaching and exceeding the goals our bosses have set for us, many will conspire to keep us where we are because we can be relied upon to perform. And they will justify their self-serving decision by pointing out that we have not shown enough leadership potential.

Jeff was so busy solving problems as they arose that he never stopped to put in place clear operating guidelines and performance objectives to guide his team. He failed to notice that his successful market strategy had run its course and that the operation needed a new post-turnaround direction. His constant intervention undermined the development of his key talents two or three layers below. Instead of working through his team, he was working for them. All this came at a cost: although he was working 24-7, neither his team nor his superiors were happy.

Because most of us come to define our jobs in terms of our core strengths and skills, similar versions of this story play out whenever we are asked to move from the familiar to the unfamiliar. We have difficulty making the transition from work firmly rooted in our own functional knowledge or expertise to work that depends on guiding diverse parties, many outside our direct control, to a shared goal—that is, the work of leadership. The sidebar “How Do You Spend Your Time?” illustrates the importance of making this transition.

Understand What Leaders Really Do

What muscles should Jeff be strengthening instead? To answer this question, first consider the age-old distinction between management and leadership.6 At its essence, management entails doing today’s work as efficiently and competently as possible within established goals, procedures, and organizational structures. Leadership, in contrast, is aimed at creating change in what we do and how we do it, which is why leadership requires working outside established goals, procedures, and structures and explaining to others why it’s important to change—even when the reasons may be blatantly obvious to us.

When doing our routine work, we’re asking, “How can we do the work better (i.e., faster, in a less costly way, with higher quality)?” We spend our time with our teams and current customers, or on our individual contributions, executing on plans and goals to which we have committed. We usually know what we’ll get for the time, effort, and resources we invest. We have faith that we’ll meet our goals because we are using the skills and procedures that have worked for us in the past.

When doing leadership work, we’re asking, “What should we be doing instead?” We spend our time on things that might not have any immediate payoff and may not even pay off at all. For example, we might be looking beyond our normal functions to envision a different future. Because transformation is always more uncertain than incremental progress (or decline), belief in the rightness of a new direction requires a leap of faith. We are more inclined to take the leap when the change engages us and when we buy into not only what the leaders do but, more importantly, who they are and what they stand for. In other words, to act like leaders, we will have to devote much of our time to the following practices:

• Bridging across diverse people and groups

• Envisioning new possibilities

• Engaging people in the change process

• Embodying the change

Become a Bridge

Consider the conventional wisdom about how to lead a team effectively: set clear goals; assign clear tasks to members; manage the team’s internal dynamics and norms; communicate regularly; pay attention to how members feel, and give them recognition; and so on. These are important things to do, but they may not make much of a difference to your results.

In study after study over more than twenty years, MIT professor Deborah Ancona and her colleagues have consistently debunked this widespread belief about effective team leadership.7 They found that the team leaders who delivered the best results did not spend the bulk of their time playing these internal roles. Instead, the best leaders worked as bridges between the team and its external environment. They spent much of their time outside, not inside the team. They went out on reconnaissance, made sure the right information and resources were getting to the team, broadcasted accomplishments selectively, and secured buy-in from higher up when things got controversial. Moreover, successful leaders monitored what other teams—potential competitors, potential teams from whom they could learn and not reinvent the wheel—were doing.

Take, for example, a former BP manager named Vivienne Cox. When she took charge of a newly formed Gas, Power & Renewables group, she inherited a number of small, “futuristic” but peripheral businesses, including solar and wind energy and hydrogen gas. A neophyte on alternative energy, Cox gathered inputs from a broad group of outsiders to her group and company to analyze the business environment and to brainstorm ideas. These conversations brought to light the urgency of moving away from a purely petroleum-based business model.8

Cox is a classic example of the leader as a bridge between her team and the relevant parties outside the team. She chose a “number two,” who was complementary to her in his focus on internal and company processes, while she herself maintained a strategic, external, and inspirational role. She spent much of her time of talking to key people across and outside the firm to develop a strategic perspective on the nature of the threats and opportunities facing her nascent group and to sell the emerging notion of low-carbon power to then CEO John Browne and her peers. Her network included thought leaders in a range of sectors (more on this in chapter 3). She placed outsiders like her strategic adviser in key roles to transcend a parochial view. And Cox brought in key BP peers like the heads of technology and China to make sure her team was also informed by those who saw the world with a different lens.

Once she had a strategic direction in mind for her alternative-energy business, Cox activated her network to spread “sound bites” about the alternative energy industry across the company. She explained: “It can be so helpful to make a comment here, have a conversation there—it’s the socialisation of facts and ideas, creating a buzz. It’s much more important than presentations. If it works well, you create a demand for the information—they come to you to ask for more.”9

Another good example is Jack Klues, former CEO of Vivaki, the media-buying arm of Publicis Groupe. Publicis had consolidated many separate media operations to increase its purchasing power with the likes of Google and Yahoo and to consolidate expertise in digital advertising. The job entailed weaving together disparate talents to exploit the new economies of scale. Klues described his role: “I’ve always thought my job was to be a ‘connector.’ I see myself as connecting interesting and smart pieces in new and different ways … I was the one person about whom the other twenty media directors could say: ‘Yeah, we’ll work for him.’ And I think they all thought they were smarter than me in their particular areas, and they were probably right. But the job was about bringing the parts together. I didn’t get the job, because I knew something they didn’t know, and that something became the Holy Grail.”10

Table 2-1 outlines two contrasting roles team leaders play. When you play a hub role, your team and customers are at the center of your work; when you play a bridge role, as Cox did, you work to link your team to the rest of the relevant world. Both roles are critical. What role was Jeff playing? He was clearly a hub. But when people rate the effectiveness of leaders, guess which ones come out on top? The bridges. Leaders who focus on the right-hand column outperform the leaders on the left at nearly every turn.

TABLE 2-1

Are you a hub or a bridge?

| Hub roles | Bridge roles |

|

• Set goals for the team

• Assign roles to your people

• Assign tasks

• Monitor progress toward goals

• Manage team member performance; conduct performance evaluations

• Hold meetings to coordinate work

• Create a good climate inside the team

|

• Align team goals with organizational priorities

• Funnel critical information and resources into the team to ensure progress toward goals

• Get the support of key allies outside the team

• Enhance the external visibility and reputation of the team

• Get recognition for good performers and place them in great next assignments

|

No matter what kind of organization you work in, team leaders who scout ideas from outside the group, seek feedback from and coordinate with a range of outsiders, monitor the shifting winds within the organization, and obtain support and resources from top managers are able to build more innovative products and services faster than those who dedicate themselves solely to managing inside the team. Part of the secret of their success is that all their bridging activity gives them the outsight they need to develop a point of view on their business, see the big picture organizationally, and set direction accordingly.

Do the “Vision Thing”

Of course, a leader can form a bridge across boundaries but still focus on the wrong things. Even so, the external perspective gained by redefining your work more broadly is a key determinant of whether you, as the leader, will have good strategic ideas. More importantly, an external perspective helps you translate your ideas into an attractive vision of the future for your team and organization.

Broad vision is not an obvious job requirement for many people, including former US president George H. W. Bush. When asked to look away from the short-term, specific goals of his campaign and start focusing on a future to which his voters might aspire, he famously replied, “Oh—you mean the vision thing?”

Although Bush derided the idea of broad vision and although execution-focused managers underplay its importance, the ability to envision possibilities for the future and to share that vision with others distinguishes leaders from nonleaders. Large-scale surveys by the likes of leadership gurus James Kouzes and Barry Posner bear out this observation.11 Most people can easily describe what is inadequate, unsatisfactory, or meaningless about what they are doing. But they stay stuck in their jobs for lack of vision of a better way.

Across studies and research traditions, vision has been found to be a defining feature of leadership. But what does it look like in action? The following capabilities or practices are some specific ways good leaders develop vision.a

Sensing Opportunities and Threats in the Environment

• Simplifying complex situations

• Seeing patterns in seemingly unconnected phenomena

• Foreseeing events that may affect the organization’s bottom line

Setting Strategic Direction

• Encouraging new business

• Defining new strategies

• Making decisions with an eye toward the big picture

Inspiring Others to Look beyond Current Practice

• Asking questions that challenge the status quo

• Being open to new ways of doing things

• Bringing an external perspective

a. Manfred F. R. Kets de Vries, Pierre Vrignaud, Elizabeth Florent-Treacy, and Konstantin Korotov, “360-degree feedback instrument: An overview,” INSEAD Working Paper, 2007.

Just what does it mean to be visionary? Most everyone agrees that envisioning involves creating a compelling image of the future: what could be and, more importantly, what you, as a leader, would like the future to be.12 But the kind of vision that takes an organization forward doesn’t come from a solitary process of inspired thought. Nor is it about Moses coming down from the mountain with the tablets. It’s certainly not the mind-numbing vision statement crafted by the typical organization. The sidebar “What Does It Mean to Have Vision?” lists numerous important capabilities that contribute to true strategic vision.

Let’s examine how Vivienne Cox acquired her vision. Her prior role had been to run BP’s oil and gas trading operation according to clear-cut, BP-specified performance indicators and planning processes. In her new role, she had to decide what to do about all the bits and pieces of alternative-energy business that had sprouted around the edges of the organization and see if they might fit together. After much bridging to external sources of insight—and this included asking herself and key stakeholders whether BP should, as a big oil company, be in the alternative-energy business—she and her team started to coalesce around a low-carbon future that made sense at BP. Cox next asked, “What should be our ambition?” The conversations that ensued focused on where to compete and on what basis the Alternative Energy group might expect to win. Only much later did her group develop business plans specifying targets such as deal volume and market share.

As Cox’s example shows, crafting a vision entails developing and articulating an aspiration. Strategy involves using that aspiration to guide a set of choices about how to best invest time and resources to produce the result you actually want. Both are a far cry from participating in the organization’s annual planning process, as Roger Martin, former dean of the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, has repeatedly explained.13 In annual planning, there is a clear process for producing and presenting a document consisting of a list of initiatives with their associated time frames and assigned resources. At best, an annual plan produces incremental gains. Envisioning the future is a much more dynamic, creative, and collaborative process of imagining a transformation in what an organization does and how it does it.

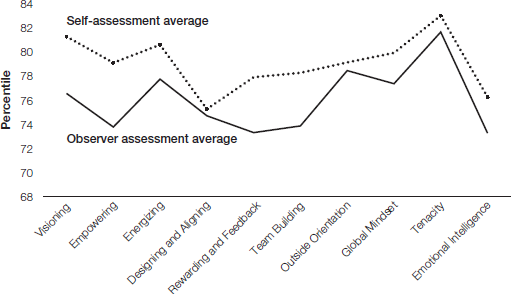

Many successful and competent managers are what I call vision-impaired. In the 360-degree assessments of the managers who come to my programs, envisioning the future direction of the company is one of the dimension of leadership competency on which most participants invariably fall short, compared with other skills such as team building and providing rewards and feedback.14 Figure 2-3, taken from a summary of feedback from 427 executives and 3,626 observers, shows the notable gap between how these managers see themselves and how the people they work with—juniors, peers, and seniors—view the managers with respect to vision. The gap between the managers’ self-perceptions of their envisioning skills and the views of their superiors is even bigger.

FIGURE 2-3

Mind the gap: 360-degree assessment of leadership competencies

Note: Table based on a sample of 427 executive education participants and their 3,626 observers. “Envisioning the Future,” one of the two competencies (along with “Empowering”) with the lowest scores and largest gap between the self-assessment and observer scores, as compared with other competencies such as “Designing and Aligning” and “Outside Orientation.”

Asked to explain the gap, many managers say that their job is to implement what comes down from the top. They believe that strategy and vision are the purview of senior managers and outside consultants who formulate grand plans and then hand them off for execution to the rest of the organization.

Historically, strategy and vision were indeed handed down from the top. But technology has profoundly altered that neat division of labor, eliminating many of the tasks—performance monitoring, instant feedback, and reports and presentations—that were staples of managerial work even five years ago. Increasingly, executives are required to shift their emphasis from improving current operations and performance indicators to shaping a common understanding of the organization’s present environment and its desired future direction. When an empowered front line is in constant contact with customers and suppliers, and these same customers and suppliers increasingly participate in the innovation process, vision and strategy are no longer the exclusive purview of the CEO. Fast-cycle response and coordination depends on the layers of strategists beneath the C-suite. But we’ll never figure out vision and strategy if we remain shut up in our offices, as Jacob tried to do.

Engage, Then Lead

No matter how much strategic foresight you might have and how compelling your ideas, if no one else buys in, not much happens. Nor do people buy in for abstract, theoretical reasons; they buy in because you have somehow connected with them personally.15

Kent, a division manager for a tech company that was having trouble adapting to new marketplace realities, learned this lesson the hard way. He had developed a clear and strong point of view about what his company needed to do to provide more integrated solutions for its customers and to better serve some underexploited markets. And he was determined to push his vision through the organization, damn the torpedoes. But he failed to bring people along. One day, he invited a consultant he knew well to sit in the audience as he gave his PowerPoint pitch to a cross-functional team. Kent drove through a long and complicated set of slides and was visibly surprised when his audience alternated between indifference and pushing back on his ideas.

“You heard me say some important things,” Kent told the consultant, “but everyone went to sleep. What happened?”

Admitting that the points Kent made were important, the consultant nevertheless told him why people tuned out: “You didn’t build any bridges to those who didn’t immediately agree with you.”

Years later, Kent understood what had gone wrong. “I had a vision,” he recalled, “and I was waiting for everyone else to agree. I was not going to put my vision out for revision—it would fly as it was, or not.”

Kent hadn’t realized that the quality of a leader’s idea is not the only thing people consider when making up their minds about whether to engage with the leader. Naive leaders act as if the idea itself is the ultimate selling point. Experienced leaders, on the other hand, understand that the process is just as important, if not more so. How they develop and implement their ideas, and how leaders interact with others in this process, determine whether people become engaged in the leaders’ efforts.

A simple formula summarizes what I have concluded are the three key components for success in leading change:

The idea + the process + you = success in leading change

I came to this formula after noticing an interesting pattern in my classes when we analyze a written case study and the effectiveness of the leader-protagonist. My students rarely discuss what the protagonist is actually advocating, and they talk even less about the outcomes his idea has produced.

Process is hugely important not because results are unimportant but because most change efforts have long-term horizons and because results take time. People make up their mind about whether they want to buy in much earlier, while the initiative is still in progress and the jury is still out on its ultimate success. Consciously or unconsciously, they are looking for clues about whether the initiative will succeed and what success means for them, and they use those clues to place their bets.

So, the bulk of people’s attention is devoted to the process the leader uses to come up with and implement the idea: Was the leader inclusive or exclusive, participative or directive? Did he or she involve the right people and enough of them? What levers is the leader using, and are they the right ones? Table 2-2 shows how all the classic steps involved in leading change involve personal choices that are based on the leader’s stylistic preferences.

TABLE 2-2

Steps and styles in leading change

| Key steps in leading changea | Stylistic choices that influence the change process |

|

• Create urgency

• Form a guiding coalition

• Craft a vision

• Communicate the vision

• Empower others to act on it

• Secure short-term wins

• Embed the change in the organization’s systems and processes

|

• Where do I get my information?

• How much do I involve others?

• What people do I involve?

• How many?

• How will I sell my ideas?

• What should my role be?

• How fast should we go?

|

a. See John Kotter, “Why Transformation Efforts Fail,” Harvard Business Review 73, no. 2 (1995): 59–67, for a classic treatment of key steps in leading change.

All of these “how” facets of the leader’s behavior increase (or erode) people’s willingness to give the leader the benefit of the doubt and increase (or erode) their faith that eventually the results will follow. In other words, people create a self-fulfilling prophecy: if they have faith in the leader, then they will cooperate and commit, thereby increasing the likelihood of success. Inexperienced leaders don’t just overly focus on the idea; they often try to jump directly from the idea to a new structure to support it without passing through the necessary phase of showing what their initiative looks like and what its desirable results may be. The sidebar “A Tale of Two Chief Diversity Officers” shows the drastically different outcomes that can result when leaders either engage their people or fail to do so.

Probably one of the hardest leadership transitions is the move from a line job with a clear time horizon and financial results to a support role in which the job is to influence those with bottom-line responsibility. It’s even harder if the support job involves something that many managers espouse but that is actually at the bottom of their list of priorities, like diversity. That’s the situation faced by new diversity officers—the people charged with putting in place a system to help the organization become more diverse and inclusive—and the situation is often made worse if they are novices to the subject. That’s also why many companies have implemented diversity initiatives without seeing much by way of results.

Recently I observed two people take charge as diversity chiefs. Both people were in financial services firms, both moving into the role from the business side, and both without experience in this area.

The first, Nia Joynson-Romanzina, the head of global diversity and inclusion at Swiss Re, sought first to find out what the company thought about diversity and how it could think differently.17 She started by knocking on doors and talking to executive committee members and group board members. “It became very clear that we were divided into two camps,” she told me in an interview. “One wanted to get more women in leadership; the other camp said, ‘If this is all about women, count me out.’ I realized very quickly that this is a very polarizing topic.”

But her conversations revealed that a commitment to diversity of thought and opinion was the one thing that brought everyone together. She explained: “That gave me an understanding of the extent to which gender diversity can be polarizing, while the notion of diversity of thought and opinion was something that everybody could buy into. It evolved naturally into a discussion around inclusion.”

As she went about her internal discussions, Joynson-Romanzina also identified the key external conferences, working groups, and thought leaders that might inform her approach. She concluded that although Swiss Re was already a diverse company, unconscious biases were discouraging employees from grabbing the next rungs on the ladder or including others in their teams.

A chance to show what was possible came her way when a change-minded, newly appointed CEO of a Swiss Re business decided that although business was going well, the company could benefit from the infusion of new, more diverse talent. He opened up all the most senior management positions, encouraging everyone to apply. Success would mean being more client-centric; a diversity of viewpoints, genders, culture, education, skills, and so on was a key factor in achieving this.

Shortly before applications closed, the CEO noticed the lack of diversity in the list of candidates; virtually no women were applying for the roles. While scratching his head, he consulted with Joynson-Romanzina, who told him to look beyond his existing network. “Women are less likely to feel qualified, even when they are,” she explained. “You need to go out and tell women, and men, very specifically that they should be applying. There is no guarantee that they will get the job, but they should at least apply.”

He did just that, extending the application deadline to allow the effort to take effect. A diverse hiring team was brought on board and put through training about unconscious bias. Also, Joynson-Romanzina was invited into the room to join the decision making to challenge any unconscious biases and to ensure an equal playing field for all.

The CEO ended up with an executive group with much greater cross-functionality and generational balance and a female representation of over 40 percent, up from 17 percent before the exercise. In each position, the best person won the job, and there was consensus on that.

This very visible win formed the basis of Joynson-Romanzina’s vision and strategy to address diversity shortfalls and enhance the inclusion of employees. While many companies begin by setting numerical targets, she concluded that starting with a numbers focus would raise resistance and distract from the fundamental and long-term change that had to happen. “This is about changing mind-sets,” she said. “Include first, and the numbers will follow.”

The second diversity officer took a very different tack. She wanted to get the vision right first. For her, this meant taking inventory of what was currently in place across the widespread niches of the organization and how that mapped onto what the research was saying. Of course, she found many inconsistent practices and a great lack of coherence in what the firm was doing.

So, her first priority was to create a model to integrate the different pieces into a holistic framework. She assembled a project group to do just that. The result was a five-part model that included the full diversity landscape, from the business case to a set of cornerstone principles, to all the HR processes in which the principles needed to be embedded. Once she had a best-in-class model, she started to present it to different stakeholders. While many of them applauded the thoroughness of her effort, they weren’t quite sure what the goal was or what their part should be.

a. Herminia Ibarra and Nana von Bernuth, “Inclusive Leadership: Unlocking Diverse Talent,” INSEAD Knowledge, January 15, 2014.

Embody the Change

Of course, there is a big difference between reading about what leaders do and actually observing them in person. Our classroom conversation changes dramatically when we watch a video of the leader in action; the discussion becomes more personal, visceral, and emotional. Often, the participants are at a loss for words to explain their reactions objectively. Judgments now hinge on our personal connection to the leader: “Did I like him? Was he approachable or distant? Did he seem genuine, authentic? Was he listening to the audience, engaging them? Would I want to work with him? Does he speak to me?” Of course, the aha moment is when they realize that others react to them as leaders in the same visceral way.

A big part of stepping up to leadership is recognizing that of the three components of my formula (the idea + the process + you), the you part always trumps the idea and is the filter through which people evaluate the process. Your subordinates, peers, and bosses will decide whether your process is fair, whether you have the best interests of the organization in mind (as opposed to simply working to further your career), and whether you actually walk the talk.

What goes into that critically important you? Most people have been taught to think that it’s all about your management style. But style is only one manifestation of who you are, and many styles can be effective within the same sort of situation. What people are gauging instead has to do with your passion, conviction, and coherence—in other words, your charisma, the magic, indefinable word often used to describe great leaders.

Years ago, management professor Jay Conger set out to unveil the mysteries of charisma by getting people to name leaders they found charismatic and then observing what these charismatic leaders did.16 The leaders were a highly diverse lot in appearance, personality, and leadership style. Some of the charismatic leaders were authoritarian types; others much more collaborative. Some were personable; others, like Steve Jobs, were not. As it turns out, Conger and other researchers who have built on his work found that charisma is less a quality of a person than a quality of a person’s relationships with others.17

People were seen as charismatic, Conger and others found, when they had compelling ideas that were somehow “right for the times.” Because charismatic leaders tend to bridge across organizational groups and external constituents, they are excellent at sensing trends, threats, and opportunities in the environment and therefore able to generate sounder, more appealing ideas. But as we saw above, the idea is only one part of the equation and often the least important. The other attributes of charismatic leaders, Conger and others learned, were all about the process and the leaders themselves. These attributes had to do with how and why charismatic leaders engaged followers and what the leaders found inspiring about who they were as people. Specifically, charismatic leaders have three other things in common:

• Strong convictions based on their personal experience

• Good and frequent communication, mostly through personal stories

Take Margaret Thatcher, for example. She is still controversial today, and many people certainly disliked her.18 But she changed the course of British history by espousing a clear and simple message that she believed in passionately and that was entirely coherent with her formative experiences and personal story.

Thatcher’s signature was her legendary skill in the art of political debate. No one could marshal the facts and figures like she did. But all her knowledge and analytical mastery wasn’t enough to explain how she managed first to stand out from the pack to break into the highest levels of government and then, as prime minister, to lead her nation through a dramatic turnaround.

What distinguished her from all the other gifted politicians around her was how she used her personal experience to crystallize a powerful political message that she personally embodied. How did she inspire people to act? How did she convey what really mattered to her? She told stories about herself. About how she learned to be thrifty and stick to a budget. About how she was taught not to follow the crowd, but rather to stick to her guns. And she, a grocer’s daughter, and a woman at that, attracted a large following of people who believed what she believed.

Did you know that she grew up in a home that had no indoor plumbing? Her father believed in austerity and made no concessions for anything not essential. This and many other formative experiences profoundly shaped Thatcher’s beliefs as a politician. She used herself as a metaphor for what she felt was missing in the United Kingdom: a sense of self-determination and redemption through hard work and delayed gratification. She made meaning of her life in a way that aligned with what she wanted the British people to understand and buy into, and it was the meaning she infused into her policies, and not the policies themselves, that got them through.

Simon Sinek, whose TED talk on leadership is one of the most viewed, calls this behavior “working the golden circle.” As he explains it, most of us attempt to persuade by talking about what needs to be done and how to do it. We think the secret of persuasion lies in presenting great arguments. Through our logic and mastery, we push our ideas. This doesn’t work very well, because we follow people who inspire us, not people who are merely competent. Instead, leaders who inspire action always start with the why—their deepest beliefs, convictions, and purpose. In that way, they touch people more deeply. Thus, the why lies in the center of the golden circle of inspiration.

Make Your Job a Platform

How do you develop the capacities to bridge different groups, envision a future, engage others, and embody the change? How do you start learning to become a more effective change leader, right now where you are? You start by making your job a platform for doing and learning new things.

Among leaders who have managed to step up, this learning process is nothing like the simpler skill-building process you might employ, say, to improve your negotiation or listening skills. It’s a more complex process that involves changing your perspective on what is important and worth doing. So, the best place to begin is by increasing your outsight on the world outside your immediate work and unit by broadening the scope of your job and, therefore, your own horizons about what you might be doing instead.

No matter what your current situation is, there are five things you can do to begin to make your job a platform for expanding your leadership:

• Get involved in projects outside your area

• Participate in extracurricular activities

• Communicate your personal why

• Create slack in your schedule

Develop Your Sensors

Leaders are constantly trying to understand the bigger context in which they operate. How will new technologies reshape the industry? How will changing cultural expectations shift the role of business in society? How does the globalization of labor markets affect the organization’s recruitment and expansion plans? While a good manager executes flawlessly, leaders develop their outsight into bigger questions such as these. This attention to context requires a well-developed set of sensors that orient you to what is potentially important in a vast sea of information.

Let’s return to Sophie, whom we met earlier in this chapter. She got into trouble because her nose was so close to the grindstone that she had no idea what was going on in her company or its markets. Nor was she privy to the political fights being played out above her, the discussions about integrating manufacturing and supply, and the factions that formed around different ways of proceeding.

The more senior you become or the more widespread your responsibilities, the more your job requires you to sense the world around you. Consider the point of view expressed by David Kenny, currently the CEO of The Weather Channel:

A leader has to understand the world. You have to be far more external, more cosmopolitan, have a more global view than ever before, to define your company’s place in that, its purpose and value … I spend my time with media owners talking about how they think about digital, Facebook, … [and] what can we do to invent new pricing models. I spend time with tech companies that support new media. With clients, I am interested in things like: What did the G20 mean to [them]? How will all that debt change future generations? I also spend time with governments … I cycle back to clients, I report back on what I have heard, to help them understand that their networks will move in that direction too.19

How does a more junior leader develop sensors? Salim, who had worked as an assistant to the president of a large division of a multinational consumer-goods company before his current assignment as the general manager of a small country in an emerging economy, attributed his success to his capacity to understand the big picture:

You need to have a very broad understanding of the business. Otherwise you get completely lost when the supply chain guy calls you, speaking to you in “supply-chain-ese,” or when the finance person expects you to understand his language. This demands a certain capacity for synthesis, because there is a huge volume of stuff that is going to be hitting you from all over. If you are not able to very quickly distill and understand the big themes, you are going to be completely overwhelmed when your boss suddenly calls and pulls a question you weren’t expecting out of the hat.

When I asked Salim how he approaches his job, he talked about “developing a nose for the trends” that allowed him to take initiative:

You can’t wait and react all the time. So there are times when I will go to my boss and say, “Do you realize A, B and C?” And he says, “How did you know that?” I say, “I was looking at this report and that report and thinking about that discussion we had the last time, and this is what I have picked up in my conversations.” It is a certain capacity to manage information. You have to have your information system well ordered, so that when [my boss] calls me and says, “I need an input into this or that,” I am able to convert my knowledge into value-adding stuff.

Of course, Salim had the benefit of a stint as assistant to the CEO, a perch from which he could observe how all the dots connected.20 For those of us whose past experience has been limited to one function or business unit, the next order of priority is to find a project that broadens our vision and increases our capacity to connect the dots. Another method, as we’ll see in chapter 3, is to start working on expanding our networks.

Find a Project Outside Your Area

In my survey about what most helped people step up to leadership, one of the top items was “experience in an internal project outside my usual responsibilities.” All companies have projects that cut across lines of business, hierarchical levels, and functional specialties. For example, a global product launch can provide exposure to senior leadership, and a cross-functional project can open doors to new opportunities. Your job is to find out what these projects are, who’s involved, and how to sign up.

François, for example, worked in sales for a multinational pharmaceutical firm. Although he found his job exciting, it was not so different from his previous job in another company, and he looked forward to a promotion as business unit director in sales and marketing management. Because there were no such positions available in his company, François crafted for himself three small projects that increased both his leadership skills and his reputation with his bosses. First, he organized a business meeting for peers in France, where he was based, and in Belgium. As a result, he gained the attention of the area vice president. Next, he created and led a competitive intelligence group for the French affiliate, increasing his visibility at the European level. His work on these two projects raised his profile. Finally, the European medical director named him to a cross-functional group tasked with creating a handbook on how to identify and manage key opinion leaders. His country, France, became a pilot site, and François ran the project.

Many people hesitate to take on extra work. After all, we all struggle to claw back time for our personal lives, and project work almost always comes on top of our day jobs. But when it comes to stepping up to leadership, getting experience across business lines is a better choice than further deepening your skill base within a functional or business silo. One of my students had a great piece of advice for her classmates: “We all managed to make time for our executive MBAs while still doing our day jobs. When the program ends, don’t let the day job reabsorb the learning time. Keep that time aside, and use it to evolve your work.”

The new skills, the big-picture perspective, the extra-group connections, and the ideas about future opportunities that you gain from temporary assignments like these are well worth the investment. One of my students signed up for a project to rethink best leadership practices at his company, part of an effort to increase engagement and reduce turnover of key employees. Working across the lines showed him how to have influence without formal authority and how his former work habits had stymied talent development. The experience helped him discover an interest in consulting, and he moved into an advisory position two years later.

Indeed, in a world in which hierarchical ascension is being replaced by “jungle-gym careers” consisting of lateral moves, people will progress and develop through their involvement in “hot projects.”21 Such projects involve you in different facets of the business and in new problems that need solving and, ideally, expose you to people who see the world differently than you do.

Participate in Extracurricular Activities

When an internal project is simply not available (or even when it is), professional roles outside your organization can be invaluable for learning and practicing new ways of operating, raising your profile, and, maybe more importantly, revising your own limited view of yourself and improving your career prospects. Let’s consider an example.

Robert, a senior policy expert, passionately wanted to run one of his company’s businesses and to be held accountable for its P&L. But he wasn’t sure he was ready, and he fixated on his own lack of cross-functional experience and limited finance expertise. While his boss, Steve, agreed in principle to find Robert a bigger assignment, Steve shared the same doubts. He had mentored Robert for years, and like many well-intentioned bosses, Steve maintained an outdated view of Robert as the “junior guy.”

To prove his merit, Robert only worked harder. It was a busy time for his function as the company prepared to launch an important new product. The birth of his second child had already put a big dent in his external activities, and the new push virtually eliminated any discretionary time for things like the industry conferences he had relied on earlier to stay current. But as he became more and more frustrated about his prospects, he finally changed tack. He decided to get active again to learn about and create alternatives to an internal promotion.

At first Robert wasn’t sure where to begin, as many of the external activities he had invested in before would only lead him, at best, to a bigger staff job. One thing he hit on was an industry group focused on innovations in a product niche that his company was also exploring. Leveraging what he knew about what his firm was doing, Robert volunteered to organize a panel. One of the people suggested to him for the panel was an entrepreneur named Thomas, who held the patents for a rapidly growing new product line but who lacked the big-company experience in which Robert was so well versed. They struck up a friendship, and over time, the entrepreneur came to rely more and more on Robert as a sounding board for his organizational dilemmas.

As their relationship developed, Robert came to a newfound appreciation of the extent to which his own knowledge and experience extended beyond the confines of his daily functional responsibilities. This new awareness also had a big effect, indirectly, on how Robert did his job. He became more curious about what other groups in his company were doing, started to ask different questions, became more confident about making suggestions, and reallocated the way he was spending his time to make room for the increasing scope of his external interests. The shift was noticeable to everyone around him, and with time, his boss and peers also came to value Robert’s perspective.

No amount of introspection about his strengths and preferences could have given Robert the outsight he gained, thanks to his relationships with Thomas. Ultimately, the self-image that Robert saw reflected in the entrepreneur’s eyes helped Robert build the confidence he needed to go after a line role more aggressively and more convincingly.

David, who made the transition from his job as a specialist in project finance and leveraged finance to a leadership position as country manager for a European commercial bank, is another good example of how extracurricular activities can help you grow. His management was happy with the status quo for the foreseeable future, and the recessionary environment in Europe limited his possibilities. Fearing a career plateau, he took two steps. First, he volunteered for a large project at the head office in Frankfurt. The project required him to spend one or two days a week away from his daily work (forcing him to delegate some of the more routine aspects of his job to his team) and connected him with a handful of senior managers he hadn’t known before. Second, he joined the Young Presidents’ Organization (YPO), where he made some connections that helped him think more creatively about possible next moves. Like Robert, David was ignorant about what kind of curriculum vitae he needed to shift in a different direction, as most of the people in his company had followed a more traditional path. That wasn’t the case at the YPO, where he also learned how to frame and sell his expertise in a way that expanded rather than limited his options.

If you are feeling stuck or stale, raise your outsight by participating in industry conferences or other professional gatherings that bring together people from different companies and walks of life. Build from your interests, not just your experience. One of my students, for example, routinely looks for opportunities to speak at conferences on topics related to his experience. He recently gave a talk at his company on life in Nigeria, where he had worked for a number of years, showing a movie about daily life in Lagos, followed by a question-and-answer session with potential candidates for expatriation. These activities have been even more worthwhile than he anticipated: “I found that building your personal brand increases your chances of getting proposals to join strategic initiatives and step out of your day-to-day job for a while.”

Teach, speak, or blog on topics that you know something about, or about which you want to learn. And if there isn’t something out there that meets your needs, create your own. A sector manager for an internet commerce organization, for example, created her own community of marketing experts from different organizations by starting a monthly breakfast group. These extracurricular activities can help you see more possibilities, increase your visibility with people who can later help you land the next role or project, and, in the process, as Robert found, motivate you to shed some of the time-consuming tasks and responsibilities that no longer merit so much of your attention. The sidebar “Sheryl Sandberg’s Side Project” describes another good example of a fruitful extracurricular activity.

Most of us know Sheryl Sandberg as Facebook’s ubiquitous chief operating officer. But what really gave her the visibility she enjoys today originated with a TED talk that had nothing to do with her day job.

Sandberg was a keen observer of her environment. Noticing the scarcity of women in Silicon Valley, she identified several issues that she believed were holding women back in business. She started to share her observations, informally and in small gatherings at first. As her ideas resonated, she was encouraged to take them public. When an opportunity to speak at TED came up, she took it.

The TED talk went viral and led to other invitations, first at a Barnard College graduation and then at Harvard Business School. Just those three talks have been viewed over one million times, a level of impact that few corporate CEOs, apart from Steve Jobs, can boast. Her best-selling book, Lean In, followed, and the rest is history.

No one else before had created that level of interest in, and discussion about, issues of women in the workplace. What does this have to do with Sandberg’s work leading Facebook? The credibility the book gave her not only helped her recruit more women to Facebook but also landed her a position on Facebook’s board and expanded the reach of her network.

Communicate “Why”

The overwhelming success of the TED conferences and videos has produced a cottage industry of books and workshops that teach people how to do a TED-type talk.22 People are signing up in droves to learn because communication skills are at a premium today, no matter what we do. As we step up to bigger leadership roles, we find ourselves having to present our ideas more often and to more audiences who don’t necessarily share the same assumptions or bases of expertise as our own. So, we have to rely on the least common denominator to get our message across. That is usually a good story.

TED talks have a recipe that anyone can follow. It often starts with a story from the speaker’s personal experience; the story illustrates and motivates the main point the person wants to make. Once the audience is hooked by the story, the main points—the technical or scientific bits—are easier to follow and retain. The talk usually ends with the moral of the personal story, reminding the audience that the message, no matter how arcane, is personal. It’s embodied.

For example, author Elizabeth Gilbert begins her talk about the nature of creative genius by talking about the predicament in which she found herself after the unexpected success of her book, Eat, Pray, Love. Everyone told her, and she herself believed, that she had reached the pinnacle of success in her thirties. It would only be downhill from there. How would she motivate herself to do her job as a writer for the decades to come? She set out to answer that question for herself by researching the creative process. She learned that beliefs about creativity have changed over the centuries, from an archaic view of genius as something that visited a person, to today’s view of genius as an innate personal trait. The research helped her understand that we can’t set out to produce great creative work directly, because we don’t always have control over our inspiration. All we can do is our own part, and that’s to work daily and methodically so that we’re in place when inspiration comes.

All great stories, from Antigone to Casablanca to Star Wars, derive their power from a beginning-middle-end story structure and these other basic characteristics:a

A protagonist: The listener needs someone to care about. The story must be about a person or group whose struggles we can relate to.

A catalyst: In the beginning, a catalyst is what compels the protagonist to take action. Somehow, the world has changed so that something important is at stake. It’s up to the protagonist to put things right again.

Trials and tribulations: In the middle of the story, obstacles produce frustration, conflict, and drama and often lead the protagonist to change in an essential way. As in The Odyssey, the trials reveal, test, and shape the protagonist’s character. Time is spent wandering in the wilderness, far from home.

A turning point and resolution: Near the end of the story, there comes a point of no return, after which the protagonist can no longer see or do things the same way as before. The protagonist either succeeds magnificently (or fails tragically).

a. Adapted from Herminia Ibarra and Kent Lineback, “What’s Your Story?” Harvard Business Review 83, no. 1 (2005): 64–71.

According to psychologist Jerome Bruner, a message is twenty times more likely to be remembered accurately and longer when it is conveyed through a well-constructed story than when it is based on facts or figures. I am not sure what I would have remembered from Gilbert’s talk had she simply cited the studies and presented a model about conditions under which creative genius is manifest. But I remember well her story about her daily struggle to write after the literary world declared her an international hit. Seldom is a good story so needed as when we want others to believe what we believe so that they will act as we want them to act. From ancient times the world over, good stories like Gilbert’s relate the challenges that test, shape, and reveal the leader’s character or purpose.23 The sidebar “Elements of a Good Story” lays out the very basics that help the storyteller engage the audience.

What do you believe, and how did you come to believe it? The answer lies in your personal story: how you grew up, the experiences that shaped you, the challenging moments when you had to rise to the occasion, the personal failures that taught you important lessons.24 When we want someone to know us, we share stories of our childhood, our families, our school years, our first loves, the development of our political views, and so on. Why do we buy famous leaders’ biographies and autobiographies? We want to know more about their life growing up, about their exploits, triumphs, traumas, and foibles—not the five-point plan they put in place to increase margins. At work, though, it doesn’t occur to many of us to reveal our personal sides, and that is a lost opportunity.

You probably already know which stories are your best ones. What you need to learn now is how and when to tell them in the service of your leadership. One way to learn is to pay attention to people who are good at telling stories. What do these storytellers do? It helps even more to practice. One great advantage of the different job-expanding methods outlined above is that they also provide ready-made, live audiences for practicing telling your story.

Any context will do in which you’re likely to be asked, “What can you tell me about yourself?” or “What do you do?” or “Where are we going?”25 Start with your clubs and associations: volunteer to speak at every occasion that comes up. Or, if this is too radical a step, join an organization like Toastmasters, or take a storytelling seminar that will have you practicing in front of a safe audience of strangers. As you get better, seize opportunities inside your organization: a farewell party or the annual off-site. One of my managers happened to take a storytelling class, by serendipity, the week he was scheduled to give a big presentation to his organization. He threw out the PowerPoint presentation he’d assembled and told three stories instead. He told me he had never had such positive feedback on his speaking.

Tell and retell your stories. Rework them as you would work on draft after draft of an epic novel until you’ve got the right version of your favorites, the one that’s most compelling and feels most true to you.

Get Some Slack

Many years ago, a still-unknown management scholar named John Kotter took a handheld camera and followed a bunch of general managers around to see what they actually did (as opposed to what everyone assumed they were doing). The biggest thing that surprised him was how inefficient the most successful managers seemed to be.26

Much of their work didn’t take place in planned meetings or even inside offices or conference rooms. Often, the work didn’t even look like work. Instead they walked around, bumping into people serendipitously, wandering into their offices, hashing out deals in the airport lounge with key customers, and so on. These chance “meetings” were usually very short and often seemed random. But each manager made good use of these impromptu encounters to get information, mention or reinforce an important priority, or further develop his (they were all men at the time) relationships with the people whose paths he crossed. This seemingly unsystematic approach, rather than filling out reports or giving formal presentations, was the successful manager’s day job.

Kotter also filmed the managers’ agendas. As you might expect, the contrast between the diaries of the more effective managers and those of the less effective ones is striking. But it’s not what you might expect. The most effective managers had plenty of slack in their schedule: lots of unscheduled time. The less effective managers had diaries overflowing with meetings, travel, conference calls, and formal presentations.

The new ways of thinking and acting involved in stepping up to leadership require a precious and scarce resource—time. If you’re like most of the managers and professionals I teach, routine and immediate demands crowd out the time you need for the more unstructured work of leadership. When you are stretched to the hilt, it’s hard to ask yourself, “Am I focusing on the right things?” We fail to build in the necessary slack, precisely because time is short and there is so much to do.

In a recent book titled Scarcity, economists Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir make an interesting parallel between poverty of money and poverty of time.27 Both, they show, produce “tunneling,” a narrow focus on the short term and a seeming incapacity to delay short-term gratification for the sake of future rewards.

To make the point, Mullainathan and Shafir tell a story about an overstretched acute-care hospital that was always fully booked. With the operating rooms at 100 percent capacity, when emergency cases arose—and they always did—the hospital was forced to bump long-scheduled but less urgent surgeries: “As a result, hospital staff sometimes performed surgery at 2 a.m.; physicians often waited several hours to perform two-hour procedures; and staff members regularly worked unplanned overtime.” Because the hospital was constantly behind, it was constantly reshuffling the work, an inefficient and stressful way of operating.

As most organizations in trouble are apt to do, the hospital hired an external consultant who came up with a surprising solution: leave one operating room unused, set aside for unanticipated cases. The hospital administrators responded as most of us would: “We are already too busy, and they want to take something away from us. This is crazy.”

Much like the overcommitted person who cannot imagine taking on the additional and time-consuming task of stepping back and reorganizing, let alone giving up a precious resource for something that might or might not occur, the hospital’s managers were skeptical. But the operating-room gambit worked. Having an empty room allowed the hospital staff to react to unforeseen emergencies much more efficiently, without having to reschedule everything. It reduced overwork, and the quality of operations improved.

So it is for the overextended manager. It’s when we are at our busiest that we most need to free up time so that we can use it for the nonroutine and the unexpected. In this way, we increase our capacity to lead, as Kotter’s effective general managers did.

Add Before You Subtract

There are two very different kinds of problems in allocating your time to leadership work. The first, a difficult but tractable problem, is making yourself spend more time on the things you know are really important, but not urgent. This is hard to do, but there are tried-and-true techniques for doing so.28 The second, harder problem is changing your views about what is important.

The only way to tackle this second problem is to get involved in activities that will make you think differently about what you should be doing and why: boundary-spanning roles that make you more attuned to the environment outside your team, projects outside your main area of expertise, and activities outside your firm. These are medium-term investments without immediate payoff, so as you add them, you won’t be able to subtract much of what you used to do-just yet. The sidebar “Getting Started: Experiments with Your Job” offers ways for overextended managers to step out of their unproductive routines. Only when the new roles start to pay off will you be motivated and able to start letting go of the old ones.

GETTING STARTED

> In the next three days, start observing someone whom you consider a strategic thinker or visionary leader. Learn how he thinks and communicates.

> Over the next three weeks, find a project (inside or outside your organization) outside your area of expertise, and sign up for it.

> Over the next three months, watch some TED talks. Pay specific attention to how people tell their story to underscore the point they want to make. In your domain, find leaders who are also good at telling stories to make a point, and listen to how they do it. Sign up for a course in storytelling.

✓ Success creates competency traps. We fall into a competency trap when these three things occur:

– You enjoy what you do well, so you do more of it and get yet better at it.

– When you allocate more time to what you do best, you devote less time to learning other things that are also important.

– Over time, it gets more costly to invest in learning to do new things.

✓ To act like a leader, you must devote time to four tasks you won’t learn to do if you are in a competency trap:

– Bridging across diverse people and groups.

– Envisioning new possibilities.

– Engaging people in the change process.

– Embodying the change.

✓ It’s hard to learn these things directly and especially without the benefit of a new assignment. So, no matter what your current situation is, there are five things you can do to begin to make your job a platform for expanding your leadership:

– Develop your situation sensors.