TWO

Action Inquiry as a Manner of Speaking

On the basis of Chapter 1, you can now begin to practice action inquiry within yourself whenever you wish (though you may find, as we did in our early years of practice, that you need a lot of support to cultivate this wish). By the end of this chapter, you will have received enough guidance about how to practice action inquiry in conversations to begin practicing the interpersonal quality of action inquiry at work and in other areas of your life. You may even find you would like to share the practices with a select group of friends or co-workers. Just as we saw in Chapter 1 that the primary value for ourselves in exercising personal action inquiry is a deeper sense of integrity, so we will find in this chapter that the primary value for our relationships in exercising interpersonal action inquiry is a deeper sense of mutuality.

Let’s begin this chapter by listening in to Anthony as he makes a first try at action inquiry that leads him into a rich vein of leadership learning that transforms his division and his career. Later in the chapter, we describe a specific way of exercising action inquiry each time we speak. And we end the chapter with a specific discipline that small groups who wish to improve their leadership effectiveness can use. But first, let’s gain an intuitive appreciation for action inquiry and see how you can practice it no matter what your formal position may be in your organization or family.

Anthony’s Action Inquiry Leadership Experiments

Anthony is a staff member in a consulting firm. As a benefits consultant in the Wheeling office of an international human resources consulting firm, he has for the past two years immersed himself in the narrowly specialized world of a very complex method for comparing company benefit programs for large corporate clients. He has become one of the firm’s few experts in this method. This role fulfills his personal ambition to “do something unique to differentiate myself.”25

Now he would like to break out of his cocoon as a specialized individual contributor, and an opportunity to play a more value-added, entrepreneurial leadership role presents itself. This opportunity has two components. Anthony sees a quality improvement opportunity and he has ready access to the office’s strategic management team. The organization of the Wheeling office is a nonhierarchical one, with the office divided into 12 teams, each headed by a team coordinator who reports to the office manager. The team coordinators are plagued by a problem that Anthony feels he can help them address: shortcomings in a myriad of administrative functions such as billing, training, hiring and new employee initiation, career tracking, work allocation, and performance review. The team coordinators are supposed to oversee all these functions while simultaneously bringing in new clients and working with ongoing clients. The coordinators are constantly forced to juggle priorities amid tight time constraints. Clients, employees, and the coordinators themselves suffer the consequences.

No one has assigned him this project, but Anthony makes a significant commitment at the outset and develops a plan to help ameliorate some of the team coordinators’ problems. First, he will meet with the office manager to discuss the project, then meet briefly with each team coordinator to explain his proposed approach. Next, he will prepare questions for interviews and a survey instrument and will administer both. After analyzing the data, he will present feedback to the team coordinators at one of their monthly meetings. A collaboratively determined action plan will then be developed and implemented. In effect, Anthony has traded in the time he might have spent lamenting the ineffectual situation and blaming others for time that he’s put into imagining a creative, inquiring, mutuality-enhancing response.

With his flexible plan in mind, Anthony meets with Don, the office manager. Scheduled for half an hour, this meeting, as Anthony puts it, “blossomed into two hours of discussion about our team coordinator problems and how this project could help address them.” An important clarification occurs in this meeting. Don suggests that Anthony should make recommendations to the team coordinators after collecting his data, but Anthony responds that he does not intend to recommend solutions, “but rather to facilitate a collaborative effort involving all of the team coordinators.” We see that Anthony is sensitive to optimizing all participants’ sense of mutuality.26

Anthony proceeds with the survey and interviews. After several further discussions with Don, he decides to survey the team coordinators explicitly on their responsibilities—those they wish to retain, those they would prefer to delegate to their team members, and those they believe should be handled through a centralized office administration.

As Anthony describes his experience:

My follow-up discussions with the team coordinators were fantastic opportunities to experiment with my behavior on a one-to-one basis. They were very willing to open up and discuss sensitive subjects and were also appreciative of my efforts to make their lives easier.

Each coordinator directs a given consulting specialty. I had to constantly be aware of how to frame questions, which areas to hone in on, which to tactfully sidestep. For instance, on several occasions, I drew a chart with “market growth” and “market penetration” on the two axes (the old star/dog/cash cow diagram). While talking with the coordinator of a health care team, I marked his team in the star category, and a defined benefit team in the dog category. Should the leaders of these two teams have the same set of responsibilities? Perhaps the health care coordinator should let expenses rise to permit getting more revenue, while the defined benefit coordinator should work on cutting costs to increase profit.

In any event, the chart proved to be a perfect arena for using my framing/advocating/illustrating/inquiring skills. You can’t just tell a senior manager and expert who’s been in the business 25 years that he should change his behavior. But the components of action inquiry verbal behavior came right out of me. “Let’s talk about revenues and expenses for the next few minutes (framing). I don’t think that two separate team coordinators should necessarily share the same focus regarding profit generation (advocating). Look here on this chart. See how the pension team is at the opposite end of the spectrum from the health care team (illustrating)? Would you have them focus on the same issues (inquiring)?” It was an opportunity to increase the team coordinators’ awareness.

In the following, we more closely examine the four different “parts of speech”—framing, advocating, illustrating, and inquiring—to which Anthony refers in the foregoing paragraph. By way of concluding this story, Anthony suffered an attack of stage fright just before his final presentation at the monthly senior management meeting, not surprisingly in that he was making himself vulnerable by experimenting with new behavior while surrounded by his superiors. Despite this, the meeting itself went well. It resulted in the selection of three teams as pilots to test the notion of delegating coordinating functions so as to encourage leadership skills development by subordinates. Anthony received a promotion shortly thereafter.27

Improving the Effectiveness of Our Speaking by Interweaving Four Parts of Speech

What is it that Anthony learns about talking that begins to give him enough confidence to enter unfamiliar and uncertain realms, where everyone is senior to him in formal organizational power, but where he nevertheless speaks improvisationally as if he were among peers?

Speaking is the primary and most influential medium of action in the human universe—in business, in school, among parents and children, and between lovers. Our claim is that the four parts of speech—framing, advocating, illustrating, and inquiring—represent the very atoms of human action. If we can cultivate a silent, listening, triple-loop awareness to our own actions and to a team’s current dynamics, as we have just seen Anthony begin to do in the midst of his meetings, we can arrange and rearrange the interweaving of these atoms as we speak, peacefully harnessing the human equivalent of technological, unilateral nuclear power.

During the industrial age and the current electro-informational age, we have become technically powerful, but have not cultivated our powers of action. People who speak of moving from talk to action are apparently not awake to the fact that talk is the essence of action (and they probably talk relatively ineffectively). We are, in fact, deeply influenced by how we speak to one another. The very best managers often have an intuitive appreciation for much of what we are now saying and have semi-intentionally cultivated an art of speaking. However, most of us are rarely aware of how much we are influenced by the nuclear dynamics of conversational action. Instead of attending to the dynamic process of conversation, we focus all of our deliberate attention only on the content of the words being spoken.

Our claim is that Anthony’s speaking became increasingly effective as he became present enough to his own ongoing talking to increasingly balance and integrate the four parts of speech. In other words, if you find that your speaking is dominated by one or two of these types of speech, the recommendation is to try adding more of the other types. You can then test these claims by your own conversational experiments.

Here are definitions and examples of the four parts of speech:28

1) Framing refers to explicitly stating what the purpose is for the present occasion, what the dilemma is that everyone is at the meeting to resolve, what assumptions you think are shared or not shared (but need to be tested out loud to be sure). That is, put your perspective as well as your understanding of the others’ perspectives out onto the table for examination. This is the element of speaking most often missing from conversations and meetings. The leader or initiator too often assumes the others know and share the overall objective. Explicit framing (or reframing, if the conversation appears off track) is useful precisely because the assumption of a shared frame is frequently untrue. When people have to guess at the frame (“What’s he getting at?”), we frequently guess wrong and, because the frame is veiled, it is not surprising that we often impute negative, manipulative motives.

For example, instead of starting out right away with the first item of the meeting, the leader can provide and test an explicit frame: “We’re about halfway through to our final deadline and we’ve gathered a lot of information and shared different approaches, but we haven’t yet made a single decision. To me, the most important thing we can do today is agree on something … make at least one decision we can feel good about. I think XYZ is our best chance, so I want to start with that. Do you all agree with this assessment, or do you have other candidates for what it’s most important to do today?” (Actually, after you’ve reviewed the next three parts of speech, you will see that this example of testing a possible frame for the meeting includes all four parts of speech.)

2) Advocating refers to explicitly asserting an option, perception, feeling, or strategy for action in relatively abstract terms (e.g., “We’ve got to get shipments out faster”). Some people speak almost entirely in terms of advocacy; others rarely advocate at all. Either extreme—only advocating or never advocating—is likely to be relatively ineffective. For example, “Do you have an extra pen?” is not an explicit advocacy, but an inquiry. The person you are asking may truthfully say, “No” and turn away. In contrast, if you say “I need a pen [advocacy]. Do you have an extra one [inquiry]?” the other is more likely to say something like, “No, but there’s a whole box in the secretary’s office.”

The most difficult type of advocacy for most people to make effectively is an advocacy about how we feel—especially how we feel about what is occurring at the moment. This is difficult partly because we ourselves are often only partially aware of how we feel; also, we are reluctant to become vulnerable. Furthermore, social norms against generating potential embarrassment can make current feelings seem undiscussable. For all these reasons, feelings usually enter conversations only when they have become so strong that they burst in, and then they are likely to be offered in a way that harshly evaluates others (“Damn it, will you loudmouths shut up!”). This way of advocating feelings is usually very ineffective, however, because it invites defensiveness. By contrast, a vulnerable description is more likely to invite honest sharing by others (“I’m feeling frustrated and shut out by the machinegun pace of this conversation and I don’t see it getting us to agreement. Does anyone else feel this way?”).29

3) Illustrating involves telling a bit of a concrete story that puts meat on the bones of the advocacy and thereby orients and motivates others more clearly. For example: “We’ve got to get shipments out faster [advocacy]. Jake Tarn, our biggest client, has got a rush order of his own, and he needs our parts before the end of the week [illustration].” The illustration suggests an entirely different mission and strategy than might have been inferred from the advocacy alone. The advocacy alone may be taken as a criticism of the subordinate or of another department, or may elicit an inappropriate response. It might, for example, unleash a yearlong systemwide change, when the real target was intended to be much more specific and near-term. However, an illustration without an advocacy has no directional to it at all.

You may be convinced that your advocacy contains one and only one implication for action, and that your subordinate or peer is at fault for misunderstanding. But in this case, it is your conviction that is a colossal metaphysical mistake. Implications are by their very nature inexhaustible. There is never one and only one implication or interpretation of an action. That is why it is so important to be explicit about each of the four parts of speech and to interweave them sequentially if we wish to increase our reliability in achieving shared purposes.

4) Inquiring, obviously, involves questioning others, in order to learn something from them. In principle, the simplest thing in the world; in practice, one of the most difficult things in the world to do effectively. Why? One reason is that we often inquire rhetorically, as we just did. We don’t give the other the opportunity to respond; or we suggest by our tone that we don’t really want a true answer. “How are you?” we say dozens of times each day, not really wanting to know. “You agree, don’t you?” we say, making it clear what answer we want.30

If we are inquiring about an advocacy we are making, the trick is to encourage the other to disconfirm our assumptions if that is how he or she truly feels. In this way, if the other confirms us, we can be confident the confirmation means something, and if not, then we see that the task ahead is to reach an agreement. At this point, it is likely to be useful to switch from focusing on one’s own point of view and inquire further about how the other frames, advocates, and illustrates the issue we are discussing.

A second reason why it is difficult to inquire effectively is that an inquiry is much less likely to be effective if it is not preceded by framing, advocacy, and illustration. Naked inquiry often causes the other to wonder what frame, advocacy, and illustration are implied and to respond carefully and defensively: “How much inventory do we have on hand?” (“Hmm, he’s trying to build a case for reducing our manpower.”)

Notice that the central value running through the four parts of speech is mutuality. In advocating and illustrating, we present our own current point of view as cogently and persuasively as possible. In framing and inquiring, we extend ourselves as creatively as we can to embrace others’ points of view.

But how do we know what to inquire about, or what illustration to use, what to advocate, and how to frame the overall situation on any given occasion? The general answer is that each of these four parts of speech originates from our first-person research into the four territories of experience we discussed in Chapter 1 (see Figure 2.1).

Here is how they come together. To determine what inquiry invites the widest possible shared understanding and coordinated action in the current situation (and to hear the responses clearly), we need to attend primarily to the external world territory of experience (e.g., “What is it about the business climate now that makes you take such a strong position?”). To determine what illustration is most apt now, we need to attend primarily to the stories that our behaviors tell or embody (e.g., “The fact that you’ve interrupted me twice and are virtually shouting makes me wonder what is making you angry about this.”). To determine what strategy to advocate, we need to attend primarily to the cognitive/emotional territory of experience (e.g., “We may come up with a creative strategy for facing this market if we can figure out a way to advance what we are each fighting for at the same time.”). To discover what frame may be most inclusive and well-focused for our common activity, we need to attend primarily to the final territory of experience, the territory of intuitive intentions (e.g., “I’m realizing that if we want to keep growing this company and our leadership team over the next decade, maybe the best gift we can give it is to learn how the two of us and our two divisions can collaborate better. Is that kind of ten-year vision at all compatible with yours?”).

Figure 2.1 How the Four Parts of Speech Draw Their Timely Content from the Four Territories of Experience

Exercising the super-vision to interweave these four parts of speech may seem a poor investment to you because it sounds like a lot of work that provides virtually no unilateral, technical power to get results. Indeed, using inquiry and illustration to discover and tell truths that make us vulnerable to other perspectives may seem deeply threatening to whatever momentum we have developed (or imagine we have developed) in manipulating situations unilaterally. A large part of each of us does not want our momentum interrupted. Therefore, we are hesitant to try a true framing, advocacy, illustration, and inquiry approach because speaking like that may call forth true responses that interrupt our momentum and disconfirm our happy dreams. That is why it is most motivating to start trying conversational action inquiry in situations where we are already dissatisfied with the results we’ve achieved through our ordinary approach. Then there is little to lose by trying in a new way. But as we have already said, while such interpersonal action inquiry can enhance our joint efficiency and efficacy, the primary value to be gained is increased mutuality. Not until we ourselves transform to the point of valuing mutuality above unilateral control will we become fully comfortable with this approach to speaking.

We will not succeed in framing, advocating, illustrating, and inquiring regularly and effectively, however, until we strongly and sincerely want to be aware of ourselves in action in the present. Nor will we succeed in framing, advocating, illustrating, and inquiring effectively until we strongly and sincerely want to know the true response, especially when it questions our current frame, advocacy, and illustration. We may gradually come to feel in our bones that only actions based on truth and mutuality are good for us, for others, and for our organizations. (Developing this feeling is a lifetime journey in its own right, and we explore some of the major stages in that journey in Chapters 4 through 7.)32

Not only must we really wish to know the truth about how others are experiencing the situation, but we need to act/inquire in a way that also convinces the other person(s) that we wish to be questioned and even proven wrong. Why? Because people generally are reluctant to disconfirm another person’s frame, advocacy, or illustration. To do so directly is often thought of as rude—as making the other “lose face.” The more sensitive the question, the more important it is to illustrate why it is important to us to hear a disconfirming response if that is, in fact, the true response.

A Disciplined Way to Practice the Four Parts of Speech

Eight years ago, our associates Erica Foldy, Jenny Rudolph, and Steve Taylor formed a voluntary learning team. It meets once a month to practice action inquiry. They have helped other such groups to start as well. In their version, individuals usually present cases about significant interactions they have had (or that they plan to have). Live cases between the members of the group also occur. In fact, Anthony’s story, told earlier in the chapter, was an ongoing action inquiry project that he sought the members’ help on. The members of another such group sometimes use the immediacy of e-mail to ask for help with specific challenges they are facing that very day at work.

Rudolph, Foldy, and Taylor (2001) have written one of the few careful descriptions of how this process can work on a given occasion. The rest of this chapter presents a much-condensed version of their description. It illustrates a kind of conversation that directly supports personal self-transformation toward greater clarity, using framing, advocating, illustrating, and inquiring. You, too, can potentially create a small group of colleagues, or of outside the office friends, to discuss cases like the ones we invited you to begin writing at the end of Chapter 1.

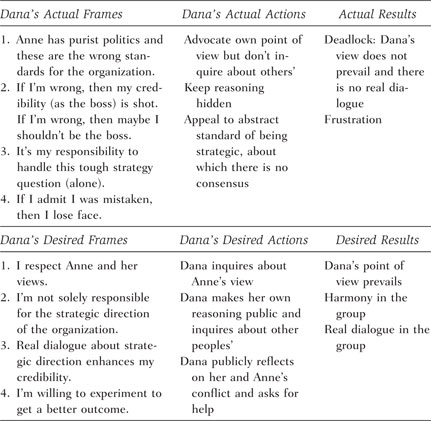

The point of working through such a case is to help the casewriter (and others) see how she or he is stymied and to avoid similar problems in the future. The grid (see Figure 2.3) provides one overarching frame-work that guides this work. Using the tools described in the following, we analyze the case and fill in the grid with observations about Dana’s implicit assumptions, actions, and results.33

In this particular case, Dana is the director at Action on Changing Technology (ACT), a union-based coalition that addresses the occupational health effects of computer technology. When this conversation takes place, Dana has been the director for less than a year. Anne, the other person in the case, predates Dana at the organization by about a year and a half. Anne hadn’t wanted the director position. Anne is very smart organizationally and politically, despite her youth. Dana has a lot of respect for her and relies on her heavily, especially when she first takes the director’s post.

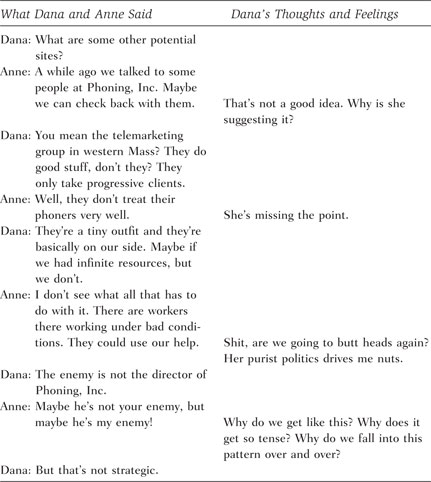

Anne and Dana had a very good relationship for the first few months after Dana arrived, but at some point it began to get strained. More and more often now, their conversations reach an impasse. In the following example (Figure 2.2), typical of the pattern, Dana and Anne argue about what sites are appropriate targets for their organization’s help. Two other staff members, Miriam and Fred, are present, but quiet, during the following exchange. Read Figure 2.2 now.

The group starts by seeking to learn what Dana’s desired results are. What does Dana want to get out of this interaction? The right-hand “Thoughts and Feelings” column of the dialogue (Figure 2.2) often provides clues about the casewriter’s desired results.

Dana’s right-hand column suggests she thinks Anne’s nomination of a target site for an educational effort is wrongheaded. She thinks, “That’s not a good idea,” and “She’s missing the point.” In the spoken dialogue Dana attempts to set Anne straight, exclaiming, “The enemy is not the director of Phoning Inc.” and when Anne retorts that maybe he is Anne’s enemy, Dana’s rejoinder is, “But that’s not strategic.” Note that all these comments, both to herself and spoken out loud to Anne, are brief advocacies related to the content of what they may do. In effect, they all come from an attention concentrated in the cognitive territory of experience. None of them relates to the process of how each is currently speaking; none of them comes from attention to the behavioral territory of experience at the time of the action.

What is the right sort of target, as far as Dana is concerned? We get a hint that it is not a small, progressive organization when Dana attempts to turn aside Anne’s suggested target by saying, “They do good stuff, don’t they? They only take progressive clients” and “They’re a tiny outfit and they’re basically on our side.” Note that these comments vary between a rhetorical inquiry (which she answers herself), an illustration (“They’re a tiny outfit”), and an advocacy. This whole part of the conversation is framed by Dana’s first inquiry about other potential sites.

Figure 2.2 Example Dialogue with Concurrent Inner Monologue

The learning group notes these patterns and asks Dana if she can clarify why she said these things. She says she wanted to influence the group to identify targets that fit her criteria. Dana could have encouraged all staff members to name potential sites, then framed a subsequent part of the conversation as an attempt to develop shared criteria for a good site. Instead, she is implicitly trying to enforce her own criteria for a good site.35

Dana also seems to be bothered by the conflict between herself and Anne. She thinks to herself, “Shit, are we going to butt heads again?” and “Why do we get like this? Why does it get so tense?” When the group queries Dana about this, she says she wants a harmonious discussion that will help the organization move forward.

By this time in the conversation about Dana’s case, the irony of Dana’s wanting a harmonious discussion in which only her point of view is allowed to prevail is plain to all, especially Dana. In hindsight, Dana notes that she had another goal in the conversation which was less obvious to her at the time and which seems to have been overridden by her desire to have her viewpoint prevail. That other desired outcome was “to have a real dialogue.” “What is a real dialogue?” someone asks. Dana says a real dialogue is one in which Anne and Dana share their views fully, listen to each other, and negotiate actively. In other words, Dana begins to realize that she holds an espoused value of mutuality (real dialogue), but that her operative value in the conversation is one of attempted unilateral control.

When we compare Dana’s “desired results” with the ones she got, we get a clear picture of the challenge facing Dana. In this case, the actual results are almost the exact opposite of what Dana hoped for. Instead of having her point of view prevail, she and Anne are deadlocked. Instead of real dialogue, they have dueling assertions. Instead of harmony, they have simmering frustration. How did this happen? If we trace counterclockwise along the grid in Figure 2.3 from Actual Results to Actual Actions to Actual Frames to Desired Frames to Desired Actions, we begin to see the answer.

We try to imagine the Desired Actions as concretely as possible. For example, one way for Dana to publicly reflect on her and Anne’s conflict and ask for help is to say:

“I feel in a dilemma here. On the one hand, I really want us to target the organizations I think are right. On the other, when I push my view I think that contributes to a pattern that Anne and I repeat over and over that has stymied us in the past: I say my view, then she says hers, and we don’t seem to have much of an impact on each other. I’m not getting my way, she’s not getting hers, and we are all just stuck. I think I’m open to influence on what the right strategy is. I believe if we worked together, we might actually come up with a better strategy than the ones Anne and I are individually carrying around in our heads. Would others of you be willing to give this a try?”

Figure 2.3 Case Summary Using a Grid

Note that to say any of this, Dana first has to detach from her advocacies in the cognitive territory of experience and pay a new kind of attention to the behavioral territory of experience. What are the advantages of exercising super-vision and saying something like what’s just been posed?

This group approach has three advantages. First, it invites the silent Miriam and Fred into the conversation, empowering them, increasing the overall mutuality within the group, and reducing the likelihood of sheer polarization between Dana and Anne. Second, it describes the deadlock in the current process, a whole realm that Dana was not directly and explicitly aware of during the original conversation. The third advantage of this approach is that it explicitly invites the use of mutual influence to generate a possible double-loop change in strategy for the organization. If Dana and her colleagues (and you!) are able to learn how to attend to the action-flow of meetings as they occur, then she (and they and you) may be able to help others mired in a similar situation.37

We now turn to Chapter 3 to address the question of how personal and interpersonal action inquiry can expand into organizational action inquiry.