SIX

The Individualist Action-Logic: Bridge to transforming leadership

In Chapters 1 through 3, we said that action inquiry centers on a process of learning. This learning process is not a mechanistic, automated feedback process producing continuous change, but is instead a bumpy, discontinuous, sometimes upending, and transformational kind of learning. This learning affords individuals and organizations a widening and deepening of vision and new capacities for learning from single-, double-, and triple-loop feedback in the moment of action.

In Chapters 4 and 5, we began to illustrate this bumpy lifetime learning process. Virtually every person goes through several action-logic transformations during early life. We begin life in a stage we call the Impulsive action-logic, which we do not discuss in this book. The vast majority of us transform from the Impulsive action-logic to the Opportunist action-logic sometime between the ages of 3 and 6. A very large majority of us proceed to transform from Opportunist to Diplomat, usually between the ages of 12 and 16. A certain proportion of us transform to the Expert action-logic by the time we are 21. Many more of us do so during the decade after we join the workforce.

These transformations are likely to be bumpy because neither we ourselves, nor, frequently, our parents, teachers, or bosses know that we are going through them. Neither they nor we are intentionally guiding us through such transformations with a developmental map, such as we are constructing here.

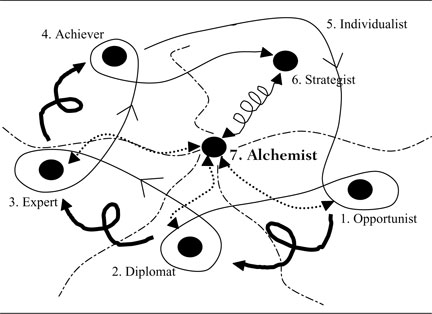

But even with a developmental map, the process is likely to remain bumpy because, like the Escher painting of the artist drawing himself, we are truly redrawing ourselves and all our mental maps in each developmental change. In fact, linear lists of the frames or action-logics are themselves misleading in that they imply a straightforward movement, with the map itself remaining unchanged. Yet that is not the personal experience of developmental transformation.92

Figure 6.1 may come a little closer to conveying some of the experiential qualities of a lifetime path of development. To illustrate the upending quality of each change in our basic action-logic, the three transformations between Opportunist and Achiever are each shown as a kind of backward somersault. Then, the Individualist action-logic is shown not as a destination, but as a path that somersaults reflectively through one’s previous history and through the growing recognition of alternative action-logics, until one reaches the Strategist action-logic (described more fully in Chapter 7). Then the journey from Strategist to Alchemist is shown as different in kind again. The double-headed arrows between Alchemist and all the earlier action-logics suggest an ongoing, time out of time process that will be discussed in Chapter 12.

The Diplomat, Expert, and Achiever follow a progression through what are identified as the conventional action-logics. The conventional action-logics take social categories, norms, and power-structures for granted as constituting the very nature of a stable reality. We are learning how to relate by gradually gaining increasing skill and control in one territory of experience after another—first, the outside world, as an Opportunist; next, the world of our own actions, as a Diplomat; then the world of thought, as an Expert; and then the interplay among all three as an Achiever. As persons operating within conventional action-logics, we typically do not recognize ourselves as seeing ourselves, others, and the world through a particular frame or action-logic. Nor do we realize that our action-logics have been transforming into different ones over the course of our lives. With the longer personal history that we gain by the time we enter our thirties, and with the greater sense of familial, organizational, and societal diversity and change with which our longer history may have endowed us, some of us begin to realize that we may be able to develop some inquiry, choice, and control over the fundamental assumptions we and others make about ourselves and the world we are encountering.93

Figure 6.1 A Late-Stage Appreciation of the Dynamics and Simultaneity of Different Action-Logics

Table 5-1 shows that in the sample of 497 well-educated, working adults in the United States, fully 90 percent score as holding conventional action-logics. Only 7 percent profile at postconventional action-logics, which include the Individualist, Strategist, and Alchemist stages, referred to as “Later action-logics” in the table. (The other 3 percent profile at the preconventional Opportunist stage.) Yet, as we will see in the rest of this book, the small percentage of postconventional leaders have a disproportionate effect on our collective capacities to transform ourselves and our institutions toward greater efficacy, mutuality, and integrity. As we learn more about the advantages of a transformational perspective, more of us may wish to embark on adult transformational journeys.

Postconventional Action-Logics

Whereas the conventional action-logics appreciate similarity and stability, postconventional action-logics increasingly appreciate differences and participating in ongoing, creative transformation of action-logics. Thus, the postconventional action-logics are less and less implicit frames that limit one’s choice, and more and more become explicit frames (like this whole theory of developmental action inquiry) that highlight the multiplicity of action-logics and the developing freedom and what we call the response-ability to choose one’s action-logic on each occasion.94

Furthermore, persons constructing these postconventional action-logics increasingly appreciate that they are exercising forms of power with others in each social interaction. They increasingly recognize that they are either reinforcing or transforming existing action-logics and structures of power as they do so. They see not only that new, shared frames can be generated in the present situation, but also that shared frames often must be generated, if high quality cooperative work is to have any chance of occurring (because members of the new team come from different national cultures, or have different skills [e.g., sales vs. accounting], or different corporate recognition and reward systems, or different action-logics).

During our journey into postconventional action-logics, we develop the capacity to think intersystemically in action about the different action-logics at play and how they mutually influence one another. No longer is the world a place of discrete objects, like billiard balls on a table, that cause subsequent events unilaterally and sequentially, based on an initially planned strategic act. Instead, causation is recognized as circular, relational, and systemic, and the assessment measures one chooses are recognized as reflecting one’s action-logic as well as feedback from the outside world. Now, for the first time, the skills of framing, advocating, illustrating, and inquiring that we introduced in Chapter 2, and the skill of seeking disconfirming feedback become more like principles of discourse than mere skills.

Other related changes occur—the principles by which we aspire to live have a stronger influence; the rules of others become less determining and are increasingly felt as a restriction of questionable legitimacy. At the same time, the question of whether we or our institutions are acting consistently with espoused principles becomes more motivating and more insistent. Likewise, the related question of how to overcome our own incongruities and avoid hypocrisy becomes more urgent. Differences within a person or organization are no longer covered-up or projected onto some external enemy or scapegoat. Instead, they are treated as the raw material for constructing a genuine integrity in action, as Steve Thompson, the underwater pipeline manager, began to do in Chapter 1.

There are many ways to develop heightened awareness of the degree to which we do not reliably act in a way that harmoniously accomplishes our intended outcomes. One is to engage in various forms of spiritual practice that aim at generating a heightened ongoing presence to ourselves. Another is to start our own small group where members present and analyze cases about specific efforts to act effectively that have not yielded the intended results (as illustrated in Chapter 2). A third is to write a critical/constructive autobiography, in dialogue with developmental theory (and possibly in dialogue with a mentor or executive coach as well).95

Art’s autobiographical writing at the end of Chapter 5 gave us a first taste of that activity, and much of the rest of this present chapter offers a fuller example of this practice. One of the authors has guided many people over the past 20 years in doing so. Celia, an African-American executive in her late forties wrote the following “career autobiography” as part of her doctoral program. Her story is an exemplar of Individualist self-reflection. As you read her autobiography, you may wish to take brief notes on incidents in your own past life that now seem to you to reflect one or another of the action-logics at work. This reflective practice can help us become more self-accepting of ourselves, as well as more accepting of others whom we today find expressing action-logics that no longer mesmerize and constrain us.

Celia, “Tracing the Roots of My Dream”

Opportunist and Diplomat

My years through college were really my Impulsive years, and I have decided not to go back that far for this discussion. Rather, I think this discussion starts after college with the Opportunist action-logic because I found myself trying to gain a skill and a sense of where my personal power would fit. I was searching for a place where I would feel comfortable. I also see that by doing this kind of assessment, I was blending in to the Diplomat frame because I found myself trying to understand others and gain a sense of their cultures and what made people make the decisions they did. I do not see a clean break between these two frames for me.

In reflecting back I realize that the first time I began analyzing the workplace was when I took on my first “real” job. Shortly after I was married, I started my first job at the Riggs Bank in Washington, D.C. I had never before experienced prejudice firsthand, but I sure did there. Tellers would make black customers wait longer for service than whites and would call them derogatory names when they were not in earshot (although sometimes I think the black people could hear them). The bank wanted me to move into training, but I had no passion for the numbers and in fact was a terrible teller. The environment just did not suit me, so I moved on.96

I became a receptionist for a major communications law firm that was also in the District. I was not challenged by the job and spent most of my time finding out what made the people tick that worked there. My error rate was abysmal and my intention was to pursue a life of mediocrity simply to provide a paycheck.

My next adventure was with the Aluminum Company of America (ALCOA). I was hired into what I understood was a quasi-professional job, tracking government contracts. It was here that I realized that I was basically a rabble-rouser at heart. I challenged secretaries for why they were still “getting coffee for their guy” and managers for why they weren’t willing to delegate tasks of any real interest. While the picture sounds somewhat dismal, I did learn a great deal. After I was finally out of the clerical functions, I was going to the Hill to Senate and House hearings on various things that affected the aluminum industry. I loved this part of the job and writing reports on trends for the plant managers.

Next, I was interviewed by the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) for the administrator position to one of the directors. The culture of AFSCME fit me, and I was molding my actions to succeed in the union. This was the first acknowledgement or even understanding that I was cut out to be an agent of change. I loved working for AFSCME. It became a real cause for me. I learned about ways to help employees gain fairness from their employers and the power of collective bargaining and written contracts. I became a labor zealot.

I met Alex in Boston in 1976, the weekend after the 4th of July. He was in charge of a SWAT-like team that was put together to settle a strike of the Massachusetts State Employees over contract negotiations. He pulled the whole initiative together and really created a strong presence with the government officials and the union members. Our story is history from there. We moved to Virginia when the strike was settled and a solid union was built. Here we worked for the national headquarters of AFSCME, traveling all over the country either managing organizing drives or settling strikes. Shortly after that we both officially divorced our respective spouses and married each other.

Expert

97

I took a stand about myself when I met Alex. This was a turning point in my life. Alex was a mentor to me. No one has had a more profound influence on my life. He helped me understand the personal power that I had and gain confidence in myself to pursue my own dreams. He is the person that taught me how to present my ideas with passion. He showed me that I could stand on my own and build a life that I wanted and not one that someone else expected for me. Alex was and is a true leader. People gravitated to him. He had a mission and he was pursuing it aggressively. He is about building people-focused workplaces where wages and working conditions are fair and conducive to productivity. Prior to this point I was very conventional and married to a guy I knew I never should have married. There was no passion for life, and my first husband had no vision for his future. Had I not met my second husband, I probably would have stayed in that dissatisfying relationship much longer.

I believe that I was moving into the Expert stage because I was taking charge of myself and beginning to master myself and my outside world. Prior to this I was unsure of myself and often did not feel competent. I was the youngest of a family of very high achievers. My mother’s favorite statement about me was that I was the “loving one,” implying that I lacked the genius of the others. Meeting Alex brought me into my own. I was going to do things now because I thought they were right for me not because others thought so.

My life for the next few years became one of exploring the new me. I was far enough removed from my immediate family that I could really find out who I was. I was also madly in love with Alex. I was continuing to develop a deep passion for the trials of workers and becoming really focused on the inequities of the workplace. However, another perspective was emerging—the political nature of institutions, both labor and companies. Many things were done in the name of good for the worker that were often more good for the union and its long-term survival and less for the worker. I saw corrupt union officials and managers who would stoop to almost anything to maintain their power.

Regression to Earlier Action-Logics

Alex was eventually recruited from this position to head up human resources at the Office of Social Services in New Jersey. I was offered a position with a joint labor/management committee to help establish areas of partnership between labor and management—although those words were not used then.98

I threw myself into this job. I had a rough beginning. In retrospect I believe that I had dropped back to the Diplomat frame as I was trying to adapt to this new work environment. At times I think I was also operating from an Opportunist perspective. Both of these approaches probably made it harder for me than if I had known about these differences and had the foresight to stay in the Expert mode.

I also had not made the mental change from being adversarial to collaborative. I was confrontational in style, I talked at people to convince them rather than to bring them in, and did not know how to listen in constructive ways. I was threatened if someone challenged my point of view and I tried to argue them over to mine. I was angry because no one thought the work we were doing in the pilot employee involvement efforts was significant.

My husband, however, was off in his own world at this time. I never knew or asked what was consuming him and did not want to know. I believe that he was taken by the power of his job. This was a dark period for me. I considered getting a divorce, but I truly loved Alex and could see us together. Life without him did not seem like a viable option. We needed to work this through. To this day I am not sure he knows how serious this dark year and a half was. I still see vividly what was going on and feel my loneliness. This whole period after the pilot fizzled is what I would characterize as a period of dormancy.

Transition Toward Achiever

What should I do? I needed to believe that I was smart enough to be successful, but what did I need to do to grow? I decided to go to graduate school. If I could not get real fulfillment on the job, I would learn more so I could contribute more. Somehow Alex came back into focus for me—he was there again. Maybe this is because I got focus for myself. He drove me to take the GREs and waited for the exam to be finished. He cheered me on when I thought I did not do well (which I did not). He supported me all the way in getting through my master’s degree. It seemed as though every day I was applying to the workplace something I had learned in school. I graduated with flying colors, which was totally affirming to my ability. It restored my self-esteem.

My role became an internal consultant to state agencies. I worked with senior managers who wanted to change the way they lead their organizations and try different models. I started to move into the maverick situation again. I had a passion for organization development. I was, however, much less dogmatic and more facilitative and interested in discovery. It seemed like such a natural progression from where I was. Again, I was out front of my colleagues. This time, though, I was not scared to be. I was pursuing a dream that fit and I knew was my destiny.99

During this period my mother died very unexpectedly. This had a profound impact on me. I was unprepared for how much I would mourn her loss. Maybe it was because I was finally coming to grips with our relationship. I was learning so much about myself and how to build positive relationships—those based on dialogue and understanding and not debate—that I was finally able to dialogue with her and not feel threatened or put down or defensive. Here, I got a first Individualist taste: my mother’s perspective was no longer oppressive and to be avoided. Instead, her perspective and mine now seemed deliciously different and to be savored. But she died before I could really come to closure with her on our relationship. I think she will never know how significant she was in shaping my life. Perhaps that is why I resented her so often. I think I cried for my mother every day for two years, usually when I drove to work by myself. She always flooded in. In many ways she kept me going because she would have been so proud of me getting my master’s.

From here I landed my dream job. I became the director of quality for a state agency. I was part of the executive team and in charge of consulting to that team relative to total quality system implementation. I had been working all this time for an opportunity of this magnitude. I was calmer about the role I was playing and I did not need to be so central as I had before. I was more secure about myself, who I was and what I brought to the table. But all exciting periods end. The ending here was hard again. The commissioner changed due to a change in the political environment and the emphasis on organizational change and quality diminished. I was crushed. I still could not quite get full endorsement. It was time again to move on. It moved me to the next plateau of learning, but before this happened I again went into dormancy.

The Individualist Journey

Alex again faced career change, and this time it was not so positive. I always had faith that he would regroup, and he did, but this time it was more of a struggle. I was now in limbo and so was he. The halcyon days were in the distance. But I realize now what strength we both have together. I could no longer stay with the state both financially and because the luster was gone. Alex was no longer there and the joy of being in the same business was gone. We were in a financial upheaval and something needed to be done. I was moving from holding the secondary career to holding the primary career. I was not prepared for this change, but in looking back it seems my whole life was about coming of age for myself, coming to really be me and making my dream come true.100

I was canvassed by several firms in New York City for potential positions. After consultation with my husband I decided to venture forth. In truth, I was flattered by the potential, but also scared. Moving from the public/labor sector to the private/management sector would mean a whole lifestyle change for me that I was not sure I was prepared for. At any rate, I went to the interviews and cried all the way home because I knew that I was going to be offered a job and would be making a critical change in my life. The first job fell through, and I was crushed. I had worked all the issues through in my mind and with my husband, and we were ready to go.

My old job became unbearable. Fortunately, more offers were coming my way and I received a wonderful offer from Chemical Bank. I landed a job at a vice-president level heading up professional development for one division.

Being at Chemical was like I always belonged there. I knew what to do and how to do it. I knew how to pull together a department and how to deal with the executives in the company. In reality I had been dealing with executives all my life—my husband was one and in many ways so was I. I quickly moved into the role of strategist to the business heads after I launched a successful executive development program. The business relied on me for quality improvement advice, and I was slotted to become the quality officer for the business after I had completed my tour of duty at the head of professional development. I was doing global initiatives, working with the sales force to improve their performance measures and streamline their pipeline reporting process. It was really a dream job and I was doing well at it.

Then the merger hit and all things creative and strategic of the sort I was working on came to a screeching halt. At this time I came across the Executive PhD Program I later joined and began to collect further data on it. Head-hunters were also calling, and I had time to look at other opportunities.

Today, as an internal consultant, I am less at the center of client system and more at the boundaries helping them discover for themselves. This is a real growth point for me. I no longer need to be as dominant as in the past, I have fewer answers and many more questions, and the questions center around the clients’ discovering their own strengths. I am more fluid in how I approach things. I see things more from a strategic point of view. I also recognize the power of dialogue and the negativity of debate. Ultimately I would like to run my own business.101

As her story ends, we see Celia moving from being more of a junior to her husband and her mother toward full seniority, becoming the primary career person and the senior generation in her family. She is also moving from being more of a zealot to being more of a facilitator of collaborative inquiry, even in a business environment that does not conform to her values. In this we hear resonances with the Strategist action-logic that we will explore in Chapter 7.

It is particularly interesting that, as she closes, Celia is considering leaving big business to create an environment more attuned to her own priorities. In our work, we see an increasing number of managers profiling at this Individualist action-logic, and they are frequently people who have recently left inside jobs to take a role in small consulting firms both where they have more control over their working environment and where their primary job becomes listening deeply into others’ worlds in order to facilitate transformational change. This trend may be influenced by the decreasing job security in firms worldwide. It may also derive from the increased interest in our own psychology, which, in turn, may be influenced by the postmodern, expressive trends in popular culture and technology. Or, are more and more of us responding to the dramatic signs we are receiving in the post-9/11 era that the environmental, political, business, and spiritual worlds are a systemic whole, that is calling us to optimize a triple bottom line—economic profitability, political mutuality, and ecological sustainability—rather than simple-mindedly taking sides?

Having read Celia’s story, you have likely begun to form some impressions of the kinds of thoughts and actions that are characteristic of the Individualist action-logic. Once again, we offer a summary of characteristics in Table 6-1.

Summary

The dawning of awareness of postconventional understanding may be a confusing time for us. The Individualist’s dark side includes troubled feelings of something unravelling or needing resolving, along with a sense of paralysis about how to move, because we have not yet developed postrelativistic principles.

Table 6-1 Managerial Style Characteristics Associated with the Individualist Developmental Action-Logic

102Yet this is also likely to be a time of renewed freshness of each fully tasted experience, of dramatic new insight into the uniqueness of our-self and of others, of forging relationships that reach new levels of intimacy, and of perusing new interests in the world. Excitement alternates with doubt in unfamiliar ways. If this sounds like a contradictory jumble, as the ups and downs of Celia’s story sometimes seem, then this is a fair representation of the Individualist’s experience. Looking back at Figure 6.1, you will see that there is no stopping point for the Individualist, and that he or she is in part engaged in a journey that reeval-uates all prior life experiences and action-logics.

The Individualist is a bridge between two worlds. One is the pre-constituted, relatively stable and hierarchical understandings we grow into as children, as we learn how to function as members of a preconsti-tuted culture. The other is the emergent, relatively fluid and mutual understandings that highlight the power of responsible adults to lead their children, their subordinates, and their peers in transforming change.

From the point of view of conventional-stage employees, Individualist managers tend to provide less certainty and firm leadership. This is in part because the Individualist is aware of the layers upon layers of assumptions and interpretations at work in the current situation.

Practice Immediacy

Just as the Individualist action-logic is a bridge to transforming leadership, there is a certain capacity for in-the-moment immediacy—for awareness and choice and artistic practice in the present—that is a bridge to the finely tuned performance of timely action inquiry in the later, postconventional action-logics. We suggested earlier that you experiment for one week with each new practice we offered before trying the next practice. If you have done this, you will have accumulated a number of practices to employ throughout your day. Now, you may be ready to start paying attention to how you are developing more immediacy with them.103

- When your watch alarm goes off each hour for your noticing exercise, does it take less and less time (we started with 30 seconds) to notice how you feel mentally, emotionally, and physically?

- Has it become automatic to notice how you feel as you transition from one activity to another?

- Do you find fewer and fewer surprises as you do your check-ins at meal and bed times?

- Do you find it takes less time to accurately name, for yourself, how you feel about things as they happen?

- Do you find yourself naturally incorporating how you feel about situations as you are advocating?

- Do you find yourself noticing rushing, stuffing, and closed Expert reactions sooner after the events that evoked them? Or even as they are evoked?

- Do you find yourself resisting others’ points of view less often, and expressing curiosity about their points of view more often?

- Does there seem to be less fog in your awareness? (Or does there seem to be more fog because you are more aware of how often you are foggy?)

The Next Step

The Strategist action-logic, to which we turn next, is the first general response to the question of how to lead timely and transforming change in a mutual way that invites and even sometimes challenges others to join in the leadership process. Most persons at the Individualist action-logic are eager to continue transforming in this direction.