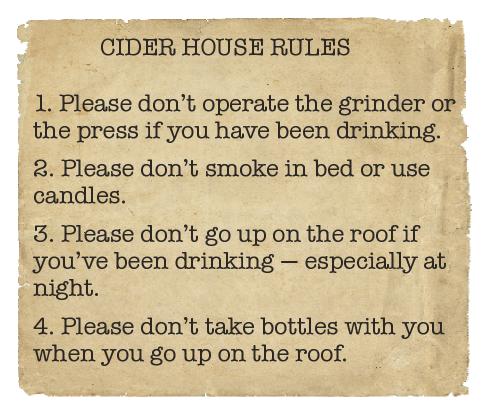

36. Cider House Rules

,

Members of the project team ignore or work around rules made by people who are unconnected to the project’s work.

The Cider House Rules, a novel by John Irving, tells the story of a group of apple pickers who return to an orchard every season to pick apples for making cider. During the weeks they pick apples, the pickers live in the old cider house. Inside it, Olive, the owner, has tacked a typewritten page headed Cider House Rules. One of the new pickers, upon reading it, can hardly fail to notice that most of the rules are being openly flouted. Inquiring about these breaches, he is told by a veteran picker, “Nobody pays attention to them rules. Every year Olive writes them up and every year nobody pays no attention.”1

1 John Irving, The Cider House Rules (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1985), p. 273.

“There are rules, and we do break them.”

—Linda Prowse

The problem with the cider house rules is that someone who does not live in the cider house—and has no intention of ever living there—is setting the rules for those who do. Olive lives in the big house and therefore does not appreciate that on hot summer nights, the roof is the only cool place to relax. Nor does she understand that drinking on the roof has become part of the apple pickers’ way of life. By setting rules that are inappropriate, she shouldn’t be surprised to discover that they are being ignored. By setting rules that are imposed on others from afar, she is asking for them to be defied.

Some development organizations have their own versions of the cider house rules. People who are not involved in project work set the rules for those who are. These organizations have a Process Improvement Office, or a Standards Group, or a Quality Department, whose task is to mandate work processes or methods. These departments might also choose tools to be used by projects or develop standards for the projects’ deliverables. These are outsiders setting rules for how a project team should do its work, potentially without any meaningful understanding of that work.

The pattern becomes more apparent when the selection of processes, methods, or tools is the only job of the selector. He does no project work; he just tells those who do the work how they should be doing it.

The outside maker of rules is rarely in the best position to determine how work should be done. When he is not intimately familiar with the work, he generally sets rules that require pointless work to be done. After all, he wants to cover all the bases (including his own rear end), and should things go wrong, his rules must be beyond criticism and absolve him of any blame. Moreover, the rule maker does not want anyone to see his rules as being in any way inadequate.

Naturally, successful project work is not complete anarchy. There must be some rules and defined processes. However, it is necessary for there to be goodness of fit between the world envisioned by the rule makers and the world inhabited by the people who are to follow those rules. The best fit comes when the process or quality specialists are regular members of the project team, or are at least closely aligned with the reality of the project’s work. Once this condition is met, the specialists are in the best position to apply their knowledge and define appropriate processes for the team. The burden shifts to the rule maker to be certain that all rules are the right rules for that project.

When the rules are appropriate, the project team will abide by them: They are useful, reasonable, and seen to be sensible. But when reality and rules differ, then reality is king, and you have cider house rules.