64. Children of Lake Wobegon

,

Photo by Marja Flick-Buijs

The manager gives performance ratings that fail to differentiate sufficiently between strong and weak performers.

In A Prairie Home Companion, public radio fixture Garrison Keillor delivers the news from the fictional small town Lake Wobegon, “where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average.”

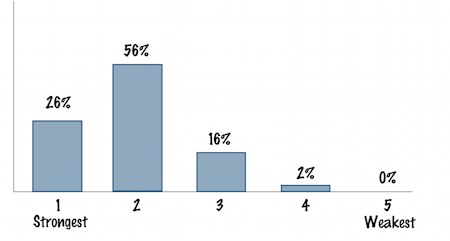

Performance ratings frequently fall into a narrow range suited only to the children of Lake Wobegon. Consider the example in Figure 64.1:

This pattern is a symptom of management’s failure to confront marginal performance and to recognize extraordinary performance. The “Lake Wobegon effect” is destructive for several reasons; first and foremost of these is that it reveals a culture of lying.

The one thing you can say with total confidence about the distribution of performance implied by the graph shown above is that it is not real. For how many decades have we seen consistent reports that individual performance in software engineering varies by an order of magnitude (or more) among the members of teams of any significant size? We accept these reported results in part because they conform to our own observations in the workplace. And yet, in far too many companies, the performance ratings turned in to HR once or twice a year tend to show relatively little variance from a near-universal “above-average” average.

The Lake Wobegon effect typically results from a combination of causes: HR-led confusion, senior management stupidity, and team leadership cowardice.

Human resources professionals create confusion when they issue contradictory guidelines for assessing and rating performance. A common example is mixing both absolute and relative criteria in the same performance-rating system. We have seen multiple examples of systems that in some places define the various levels of performance in absolute terms with respect to job requirements (for example, 1 = exceeds job requirements, 2 = consistently meets job requirements, 3 = usually meets job requirements, 4 = does not meet some job requirements, and so on). Elsewhere in the same system, a document specifies that the ratings are expected to conform to a preconceived distribution—say, 10 to 15 percent will be “1,” 20 to 30 percent will be “2,” 45 to 55 percent will be “3,” and so on. These percentages imply that the ratings are relative to the employee population rather than to some absolute quality.

Senior managers sometimes create incentives to avoid confronting employees whose performance is deficient. One of the classics is this one-two punch:

1. “We’re building a high-performing learning organization, so any employee who receives a performance rating of ‘4’ or ‘5’ must immediately be put on a performance improvement plan or ‘managed out’ of the organization.”

2. “Due to a short-term budget squeeze, all open requisitions for new hires and replacements have been temporarily frozen until further notice.”

In such circumstances, more than one manager has concluded (sometimes erroneously) that he will get more net work from a poorly performing Waldo than he would from an empty chair.

As much fun as it is to blame things on HR and bozoid executives, the most common reason managers don’t confront marginal performance lies closer to home: It’s difficult to get it right, and in any case, having a really frank discussion with a poor performer always feels terrible. So, managers put it off.

Constructively engaging with a poorly performing employee at some point requires the manager to shift roles slightly. During the early stages of performance management, the manager is in coach mode: explaining, demonstrating, assisting, answering questions, and above all, encouraging the employee. When it comes time to assess performance and to render some kind of rating, the manager has to act more as a judge. “Here is what you accomplished,” he says. “These things went well; these others left room for improvement,” and so on.

When the employee in question is not meeting the expectations of the role, this inadequacy is frequently not apparent to the employee unless and until the manager switches from coach to judge. Since this switch is relatively infrequent (rarely more than four times per year, often fewer) and is almost always uncomfortable for both manager and employee, it is easy to see how the judge role’s message can be muted or even omitted.

In addition to the Lake Wobegon effect, failing to confront marginal performance has another tell-tale symptom: the “shrink-wrapped job.” As Waldo fails—and as you fail as his manager to confront his poor performance—you may instead take things off his plate, things you need to have done right. His more-capable peers (and you) pick up the slack. This happens gradually, but before too long, his apparent performance has improved to a tolerable level. Of course, this is only so because he’s now doing far less than his role calls for.

What is so bad about using only a narrow portion of the performance-rating scale, and shrink-wrapping a few jobs? The simple answer is that it is unfair to your team members. You are lying to them about where they stand, and thus depriving them of the information they need to manage their careers.

You are lying to your very best performers by not letting them know that you know how really spectacular (and appreciated) their work has been. Let’s face it: Everyone on the team knows who walks on water, including those doing so. Recognizing such contributions is the right thing to do. If that means giving an astronomical performance rating, then do it.

You are lying to your weaker performers by not giving them an early warning that their performance imperils their employment. Sometimes, poor performance results from failing to understand expectations, and sometimes employees can—and do—correct their performance. They go on to succeed or even excel if they learn early enough that they are not cutting it.

You are lying to many of those rated in the middle of the pack by implying that the middle is larger than it really is. An excellent performer who doesn’t receive top ratings is not sufficiently recognized and rewarded. At the same time, a marginal performer receiving a “3” rating in a five-point system will feel more comfortable if 50 percent of all employees get “3” than he would if only 20 percent do.

You are telling the truth only to the truly average.