5

Ensuring Professional Excellence

Growing Talent That You Don’t Even Own

We have examined the importance of positioning the organization to better attract, welcome, and onboard agile talent. An employer branding approach enables organizations to appeal on a more targeted basis to needed external (and internal) resources. Because brand is a contract, not an advertisement, leaders must make the brand real by assessing the situation, defining needs for change, and reducing or closing the gap between what the employer brand offers and what it actually delivers.

From discussions with executives across industries, we also know that creating an environment that addresses the work and career interests of external experts is not often a priority for many organizations despite their dependence on externals. Our findings show that over half of executives see at least some potential for improvement. And, without doubt, a targeted employer brand, robust orientation and onboarding, and ongoing information sharing create a more productive environment for external talent. When leaders thoughtfully invest in building stronger connections with their external experts, they increase the likelihood that externals will do their best work and that the organization will continue to attract the skill it needs to achieve its vision and strategy.

In this chapter, we review how smart leaders ensure that their organization has the right mix of internal and external resources and that external experts have the required interpersonal skills and strategic perspective to successfully collaborate with internal colleagues. We consider three questions on this issue:

- In addition to technical or functional expertise, are there other criteria important to building the right internal-external relationships?

- How important are team skills and a bias to collaborate?

- What is the role and importance of interpersonal competence or career maturity?

From Introduction to Contribution

The framework that best describes the set of skills and behavioral competencies external experts need to thrive is called the career stages of performance. Researchers Gene Dalton and Paul Thompson of Harvard Business School and, subsequently, the Brigham Young University Marriott School of Management, developed the stages framework.1 Their work was based originally on research with R&D and engineering organizations, and was later extended by other researchers including us.2 We were fortunate to work closely with Professors Dalton and Thompson for many years at a former consultancy, The Novations Group. Their work has greatly influenced our approach.

Dalton and Thompson’s concept of career development departs from descriptions of expertise that emphasize technical depth. Dalton and Thompson found that career high performers moved through a series of four distinct stages of development (table 5-1). And as these high performers moved from one stage to the next, they were challenged to let go of the behaviors that previously made them successful, to pick up the new skills and perspective needed at the next stage.

TABLE 5-1

Career stages of performance

| Stage | How the individual contributes to the organization at this stage |

|---|---|

| Stage 1: Helper/learner | Earning trust and learning the work and the organization’s culture |

| Stage 2: Independent contributor/specialist | Demonstrating credibility and expertise |

| Stage 3: Mentor/coach | Contributing through and developing others; coordinating work between teams |

| Stage 4: Sponsor/strategist | Shaping or influencing organizational direction |

Stage 1: Earning Trust, and Helping and Learning

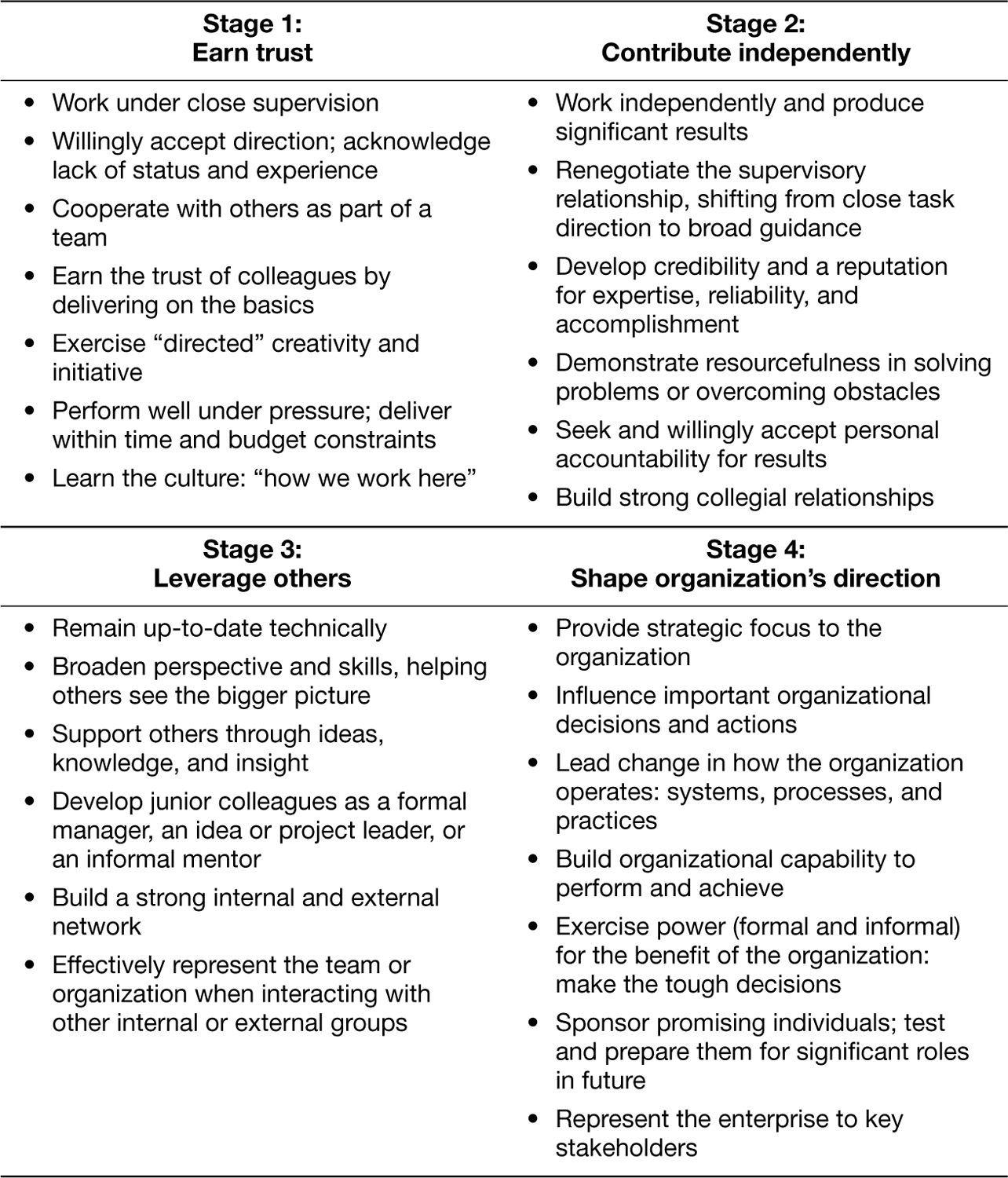

People in stage 1 are apprentices, and high performers at this stage help and learn and earn trust. The work of stage 1 is learning the ropes and developing the technical reputation, cultural insight, and relationships necessary to do the right job in the right way with the right colleagues. Table 5-2 summarizes the work of stage 1 professionals.

TABLE 5-2

What high performers in stage 1 do

- Work under close supervision

- Willingly accept direction; acknowledge lack of status and experience

- Cooperate with others as part of a team

- Earn the trust of colleagues by delivering on the basics

- Exercise “directed” creativity and initiative

- Perform well under pressure; deliver within time and budget constraints

- Learn the culture: “how we work here”

A willing acceptance of supervision is key to success in stage 1. The individual is unproven and lacks organizational status credentials. As an apprentice, the individual will be closely monitored until the person can manage his or her own work and has formed effective working relationships. Successful stage 1 professionals accept these limits and work through them.

Cultural savvy is a second critical factor, and the best performers at this stage demonstrate cultural aptitude. Every organization has its own unique way of doing things. Stage 1 professionals are expected to understand the values and norms of the organization and operate accordingly.

Creativity and initiative are important at stage 1, but until professionals demonstrate technical skill and build trusting relationships, they lack the standing to credibly recommend a better way.

At all career stages, but particularly at stage 1, mentors play a crucial role. A good mentor opens doors, makes introductions, provides practical counsel, and offers informed career guidance. Smart stage 1 professionals, and in fact professionals at all stages, recognize that reciprocity is core to any mutually satisfying relationship and certainly a mentoring relationship. We explore the topic of mentorship later in the book.

Both of us had early mentors who significantly influenced our work while we were at Exxon. Jon worked extensively with Herb Shepherd, a “father” of organization development and a cofounder of the National Training Laboratories in the United States. Shepherd taught Jon how to work with executives and to be patient in the change management process. Both of us were fortunate to have Thompson—an external—as a mentor while at Exxon.

Mentors like Shepherd and Thompson provide a mirror of reality for young (and not-so-young) knowledge workers who, in turn, work hard to show the mentor that they have what it takes to succeed. This reciprocity for both people involved in the relationship is a key to success. The apprentice learns from a more experienced and wiser professional while the mentor gets a bright, hardworking apprentice to get things done.

How long can an individual remain in stage 1? Unfortunately, some individuals never leave this stage; they do not progress technically, do not establish professional credibility, and continue to seek direction.

Stage 2: Contributing Independently

Stage 2 of professional development is the stage of the “arrived” technical or functional professional. The individual has reached technical maturity and enjoys acknowledged expertise. But while technical mojo is absolutely necessary for this stage of high performers, it is not sufficient. The professional must have the credibility and relationships to be recognized as an expert and sought out for his or her expertise. Dalton and Thompson describe the transition from apprentice to specialist as a renegotiation of the managerial relationship, from close supervision to broad navigational guidance. At stage 2, individuals are expected to demonstrate the technical expertise needed to solve difficult problems, the felt accountability to meet commitments, the resourcefulness to overcome obstacles, and the trust of colleagues inside and outside the organization. Table 5-3 summarizes the skills of stage 2 professionals.

TABLE 5-3

What high performers in stage 2 do

- Work independently and produce significant results

- Establish credibility in a specific technical or functional area of expertise

- Renegotiate their supervisory relationship, shifting from close task direction to broad guidance

- Develop a reputation for work quality, reliability, and meeting commitments

- Demonstrate resourcefulness in solving problems or overcoming obstacles

- Seek and willingly accept personal accountability for results

- Build strong collegial relationships

Ambitious stage 2 employees actively seek ways to distinguish themselves as contributors. At this stage, professionals feel the competing tugs of competition and cooperation; stage 2 people must develop the team skills to work with and influence others. Some years ago, research by the People Operations team at Google put to bed the myth of the iconic expert who waits in the laboratory for difficult challenges and heroically solves them. Expertise is as much about outreach and initiative as it is about response.

Many experts are inclined to remain in stage 2. We call the most successful among them super stage 2s. Maintaining your status as stage 2 is not an easy path, requiring an expert to stay on top of the technology advances over time. This may be a greater challenge in some technical and functional areas than in others. Some years ago, Tom Jones, an IEEE fellow and the president of the University of South Carolina, estimated the half-life of an engineering degree to be around a decade; he further postulated that over a forty-year career, a typical engineer would need to spend ninety-six hundred hours to remain current. Ninety-six hundred hours is approximately twice the number of hours needed for the original degree.3 No wonder that while super stage 2s are highly valued and often highly compensated, they are fairly rare. Functions evolve, technologies change, and recent graduates are often seen as offering technical know-how that is cheaper and more current.

Ultimately, the performance of stage 2 professional is limited by two factors. The first is their individual skill or expertise. Anders Ericcson and his coauthors were correct in citing the multi-thousand-hour rule, asserting that expertise is about practice and experience.4 The second factor is time. Regardless of how technically and interpersonally outstanding the individuals may be, experts who want to increase their productivity, status, and responsibility must figure out how to increase their contribution beyond what they can individually accomplish. That is the challenge that professionals overcome in stage 3.

Stage 3: Contributing Through Others

The key to contributing beyond your personal limits is the ability to leverage the efforts of others. This is the stage 3 challenge; at this stage, experts are expected to contribute through others. The most obvious way to do so is as a formal manager. However, there are other ways for high performers to deliver a strong stage 3 performance.

What defines effective stage 3 professionals? First, they must remain up-to-date in their technical field. Over time, breadth compensates for depth: it enables the experts to see and share the bigger picture of the technology and make the right connections between various technologies, as well as between technical and business needs. Stage 3 professionals are, in short, integrators and optimizers.5 Table 5-4 outlines the competences of this group of professionals.

TABLE 5-4

What high performers in stage 3 do

- Remain up-to-date technically

- Broaden their perspective and skills, helping others see the bigger picture

- Support others through ideas, knowledge, and insight

- Develop junior colleagues as a formal manager, an idea or project leader, or an informal mentor

- Build a strong internal and external network

- Effectively represent the team or organization when interacting with other internal or external groups

Stage 3 high performers are networkers and relationship builders: they build and maintain a strong network to get things done and keep in touch. Even more importantly, high-performing stage 3s are coaches and talent developers. Mentorship of less experienced colleagues is a hallmark of stage 3.

Stage 4: Shaping Organization Direction

The transition from stage 2 to 3 challenges individuals to break free of the limits of individual contribution. Stage 4 represents an equally significant shift: strategic guidance or influence. We think of stage 4 high performers as shaping organization direction. Primarily, this level of professional development requires an outside-in perspective, an informed point of view about the changing strategic needs of the larger organization and the ability to communicate this point of view clearly, succinctly, and persuasively (table 5-5).

TABLE 5-5

What high performers in stage 4 do

- Provide strategic focus to the organization

- Influence important organizational decisions and actions

- Lead change in how the organization operates: systems, processes, and practices

- Build organizational capability to align with strategic organizational goals

- Exercise power (formal and informal) for the benefit of the organization: make the tough decisions

- Sponsor promising individuals; test and prepare them for significant roles in future

- Represent the enterprise to key stakeholders

While these skills might seem more manager oriented than technical, typically we see many technical stage 4 contributors especially in technology-oriented organizations. A former chief geologist of a major oil company and now a senior technical leader and certainly a stage 4, describes his role this way: “My job is to ensure that our company has the tools, talent, and culture to find significant oil and gas reserves.”

The preceding discussion of stage 4 in technical fields points out a critical skill of the high-performing stage 4. Whether the position is managerial or not, the role calls for solid leadership skills. That means a vision for the future, shifting from trying to influence to taking accountability for power, and knowing how to drive the actions that produce real change.

In our leadership pipeline audits, we sometimes find a business without any stage 4 leaders. Under these circumstances, the entire organization downshifts its performance. This happens because no one is responsible to set direction or provide resources to important projects. Stage 4 leaders, whether they are managerial or technical, are key to setting the vision and providing the infrastructure under which everything else must flow. When there is confusion, there is lack of accountability and a natural tendency to mediocrity. Tough choices and trade-offs must be made, and when they are not, the consequence is poor performance.

What Drives Development

One of the most interesting findings from the career stages research is the lack of gender or age as a critical determinant of stage. Women were slightly less represented in stages 3 and 4 but not much, and the difference continues to decrease. And age just doesn’t seem to be a factor, as table 5-6 suggests. Moreover, stage development has little or nothing to do with the prestige of the universities attended, specific area of specialization, or degree. What does matter is how the individuals are managed and the opportunities offered them to grow and develop.6

TABLE 5-6

Average age of individuals by career stage

| Career stage | Average age |

|---|---|

| Stage 1: Helper/learner | 38 |

| Stage 2: Independent contributor/specialist | 38 |

| Stage 3: Coach/mentor | 39 |

| Stage 4: Sponsor/strategist | 41 |

Source: Jon Younger and Kurt Sandholtz, “Helping R&D Professionals Build Successful Careers,” Research and Technology Management 60, no. 6 (November–December 1997).

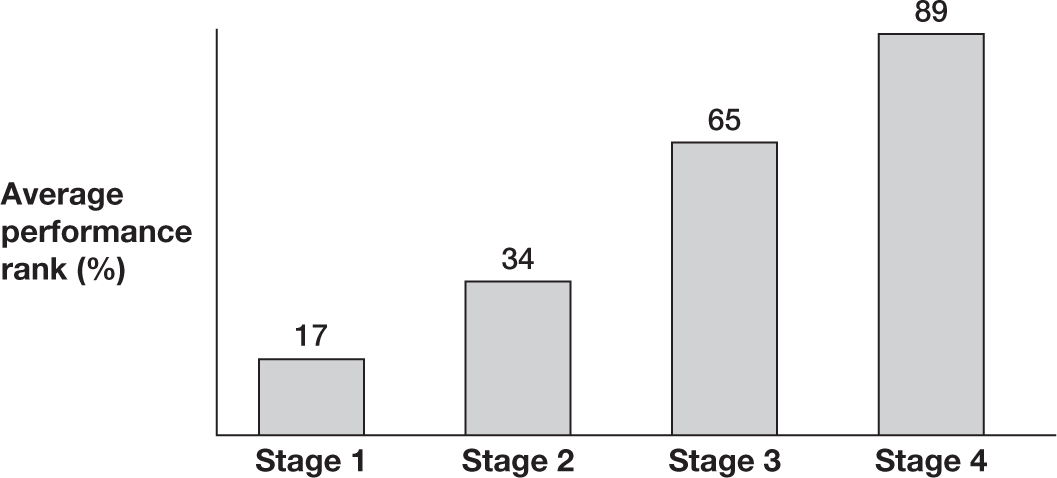

Is there a relationship between career stage and performance relative to peers? The answer is an unequivocal yes. In an IRI reported study we conducted several years ago, managers in a wide variety of technical organizations were asked to rate the performance value of their subordinates; employees were separately evaluated by stage. The data was clear (figure 5-1).7

FIGURE 5-1

The relationship between individuals’ career stage and their-perceived contribution

Sources: Gene W. Dalton and Paul H. Thompson, Novations: Strategies for Career Management (Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman, 1986); Jon Younger and Kurt Sandholtz, “Helping R&D Professionals Build Successful Careers,” Research Technology Management 40, no. 6 (November–December 1997).

Note: Briefly, stage 1 is roughly equivalent to an apprentice level; stage 2, an independent contributor or specialist; stage 3, a mentor or coach; stage 4, a sponsor or director.

How the Career Stages Help Leaders Find and Support Agile Talent

The career-stages model offers an interesting and useful way of thinking about technical experts and expertise. It suggests a number of very specific ways that leaders can improve the selection and performance of external experts.

Not Just Technical

The clear message of the stages is that technical expertise, while obviously necessary, is not sufficient. Instead, we suggest a broader way of thinking about the requirements for success for external agile talent. In our view, agile talent has the technical skill, credibility, reliability, and relationship skills to be successful. These individuals are the people whom others want to call on for help when technical skill is required.

Both the executives and technical professionals we have interviewed and taught made this point repeatedly. Technical and functional experts must be more than expert at their craft. They must be good at working with the people who will implement their products, analyses, or recommendations, and these experts must have a strong-enough understanding of the organization’s culture and norms to operate in an informed and respectful way. If they cannot meet these requirements, they will not be successful, however academically brilliant they might be. This is the reason why two equivalently technically talented individuals may have quite different career and contribution trajectories. It is also why some individuals never choose to develop beyond stage 1, or stall out in stage 2.

The career-stages research debunks the threadbare view of the expert as technical savant—the iconic scientist locked in a lab, unable to work effectively with others, brilliant but arrogant and brusque. Instead, the research findings offer a more helpful view: stage 2 demonstrates expertise and the ability to cooperate with colleagues; stage 3 shifts from the heroic individual expert to the coach and mentor who contributes through others; and, finally, stage 4 becomes the strategist and sponsor, influencing and shaping organizational direction.

Teaching and Using the Career Stages

An obvious first application of the career-stages approach to agile talent through cloud resourcing is to communicate and teach the approach as a tool in identifying resource needs and evaluating internal and external expert resources. Organizations like Exxon Mobil, Intel, Chevron, McKesson, and other leading global organizations have found career stages a helpful and easily understood framework for assessing the developmental stage of individuals and the mix of stages in a team or organization.

Match the Work and Stage

A second important application of the career-stage framework is enabling leaders to more rigorously determine the career stage required of external talents, and specifying the tasks or responsibilities to assign them. For example, a biotechnology manager who needs to add a contract researcher to his or her team traditionally describes the skills and experiences in terms of technical qualifications and work experience. Knowing which career stage the manager expects a contractor to fill adds additional precision to these specifications and focuses the search and credentials needed. What is the career stage role that this individual expected to play—stage 2, 3, or 4? Job and experience requirements would be more clearly defined. Use tool 5-1 for a simple approach to assessing the career stage of the individual and the job you hope to fill with agile talent.

We recommend a three-step diagnosis for identifying an individual’s career stage:

- WHICH STAGE BEST REPRESENTS THE INDIVIDUAL’S BEHAVIOR? First, identify which career stages provides the closest overall description of how the individual performs; the role the person adopts in relationships with colleagues, subordinates, and his or her supervisor; and the person’s competence and effectiveness in working with others. In this first step, ignore the individual’s formal role and position. Realistically, many managers operate in stage 2 despite their role as a leader and mentor, and many nonmanagers provide coaching and mentorship consistent with stage 3. It is helpful to get multiple views on the individual’s career stage. Different colleagues, with different perspectives, may experience the person’s work in varied ways.

- IS THE INDIVIDUAL IN TRANSITION FROM ONE STAGE TO THE NEXT? The career stages is a progressive rather than a prescriptive model; more often than not, individuals are in transition from one career stage to the next. This is important. If the individual is in transit, with one foot in stage 2 and another in stage 3, the role he or she plays will differ from an individual who is more fully in one stage or another. This behavior needs to be recognized. The tasks the person is assigned, whether he or she is an internal or an external resource, should reflect the transition the individual is making.

- WHAT, IF ANY, ORGANIZATIONAL AND CONTEXTUAL FACTORS MAY BE AFFECTING THE INDIVIDUAL’S CAREER-STAGE PERFORMANCE? Particularly when working with external talent, it is important to understand any extrinsic and contextual factors that may influence their performance. Organizational factors include how the individual is used, the role he or she is given, the way the person is managed, and the way that the work is communicated to others with whom the individual must work. For example, if the individual’s work director is an insecure stage 2, the supervisor is more likely to manage with a heavy hand. If internal team members are far more senior in career stage, they may discount the ability of the external resource to contribute; if they are far less senior in stage terms, it will be difficult for any real collaboration to occur. External factors may also play a role. Many individuals currently face the challenge of a young family or aging parents; both situations typically make significant demands on the individual’s time. Consequently, an individual may choose to take on a role typical of a lower career stage, making less of a demand on time and travel, in order to meet family requirements.

TOOL 5-1

Assessing the career stage of an individual or a job

Use this tool to compare the qualifications of each of the four career stages, and then decide where the individual you are assessing fits. You can also do the same thing for the job you are hoping to fill with agile talent.

Recommendations for implementing a career-stages approach:

- START WITH THE ORGANIZATION FIRST. For example, if Twitter is interested in attracting a senior software developer on a short contract basis, what does “senior” mean? We suggest it means more, or should mean more, than technical experience. Whether explicit or implicit, specifications should address the other critical success factors of a senior software developer. The career-stages approach provides an easily understood and data-based reference point.

- ASSESS THE STAGE OF INDIVIDUALS WHO MAY DO THE TASK. As we suggested above, assessing the stage of individuals is obviously important. However, when considering external agile talent, leaders may have difficulty identifying a person’s career stage during a brief interview. But stepping outside the boundaries of the interview will help. Speak with prior client organizations or colleagues who have worked with the individual in the past. As described above, share a summary of the career stages, and ask your associates which stage most closely resembles the individual’s way of working. Keep in mind that career stage is not a personality test; it is a description of how individuals go about their work at different stages of development.

- DETERMINE THE FIT. After assessing the career stage of the work to be done and the career stages of the individuals who are being considered for the project or consulting contract, identify which individual is the best fit for the work and the group. It is at this stage that the details of experience and personality come into play.

Align Peer and Supervisory Relationships

It is particularly important to ensure that there is not too great a gulf between internal and external experts working together, and especially when you are selecting internal project managers of external experts. Obviously, it wouldn’t do to have a stage 2 internal project leader managing a stage 3 or 4 external expert—but such an arrangement happens too often and is often disastrous. The flip side is equally likely to end in difficulty. A very senior project leader managing a junior external resource or team is likely to be frustrated by the quality and speed of progress. The findings of the career-stage research are clear with respect to internal project management of high-performing external experts: the internal project manager must be operating at stage 3 or higher or must be making clear, fast strides toward stage 3. If they are stage 2, the competitive tendency of that stage may reduce the performance of external talents. For example, we collaborated with a major investment bank to help them build a plan for accelerated leader development. It was a timely project that was linked to strategy business goals, and its success was a priority for senior management. Yet, a mismatch in career stage hurt its contribution. The bank appointed an ambitious young stage 2 professional to work with and support the consulting team. Instead, he saw the team as competition and insisted on controlling all communication between the consulting team and the organization. This created significant delays in completing the project, and it ultimately led to the company abandoning the project.

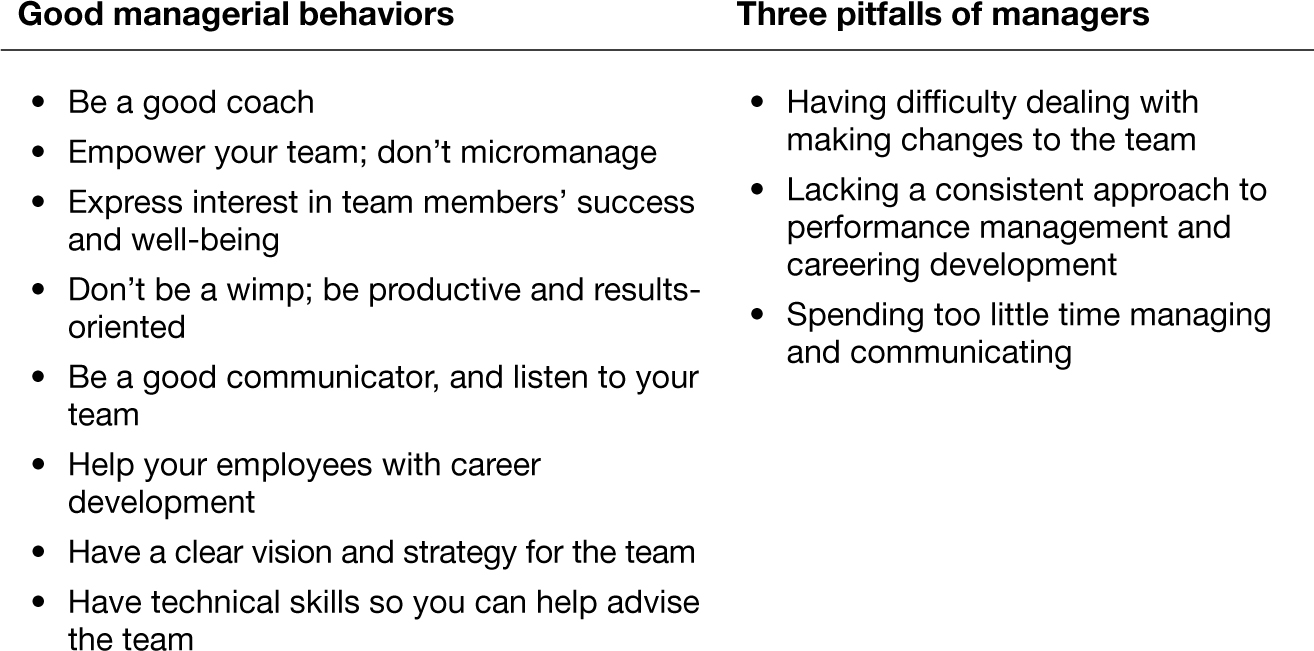

Google rediscovered the career-stages research in its internal study of “good” and “bad” managerial behaviors. Unsurprising for those of us who are familiar with the career-stages literature, but evidently an epiphany for the Google HR team, is the list of behaviors compiled by Google HR and based on extensive analytics (table 5-7). The left side of the table is a full-on description of stage 3.8

Google’s good boss, bad boss analysis

Source: Adam Bryant, “Google’s quest to build a better boss,” New York Times, March 12, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/13/business/13hire.html.

Career Stage Is Not the Same as Hierarchy

One of the common concerns about the four stages is to think of it in terms of the organization’s hierarchy. There is some truth to this as expectations change for how someone works as he or she spends time in an organization. For example, if someone is considered a high performer at age twenty-five but continues to work the same way at age thirty-five, managers ask what is wrong. In addition, there is no need to try to limit the number of stage 3 contributors. Stage 3 roles don’t need formal leadership positions. They can be technical people who have changed the nature of their contribution. Think of a business partner in IT, HR, or finance. The person assigned to the business partner role could be in stage 1, 2, or 3. As a stage 1 business partner, he or she tends to execute projects under the direction of another person. As a stage 3 business partner, the individual translates business needs into projects for his or her function. In every organization for which we have done work on this issue, there are never enough stage 3 people. Stage 3 professionals are usually the key to successful initiatives because the stage 3s who are not managers are closer to the technical work and the customer and are able to integrate the work of others to achieve effective outcomes.

Define the Optimal Mix at a Team Level

The old expression “The magic is in the mix” certainly fits the definition of the optimal distribution of career stages on a team. IBM and Microsoft are two of many technical organizations that regularly bring together mixed teams of internal software developers and external agile talent to a development team. What mix of career stages delivers the expertise required to achieve the goals of the organization?

It turns out that IBM looked carefully at this issue several years ago. Research leadership noticed that some software development teams dubbed “super teams” were many times more productive than others as measured by schedule, cost, and numbers of people. The team studied the difference between super teams and other teams.

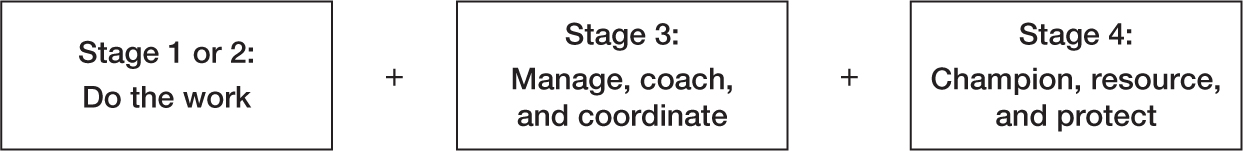

They discovered that the greatest differentiator was whether the team was staffed according to career-stages concepts. The most successful teams had the right mix of stage 1 through 4 experts at each stage of a project, operating with specific roles in mind for each stage (figure 5-2).

FIGURE 5-2

IBM super project teams: the right mix of career stages and roles

By contrast, poorer-performing project teams were under-resourced in stages 3 and 4 and typically attempted to close the performance gap by bringing on additional stage 1 and 2 professionals at critical points in time. This approach generally increased both costs and schedule slips.9

Closing the Gap

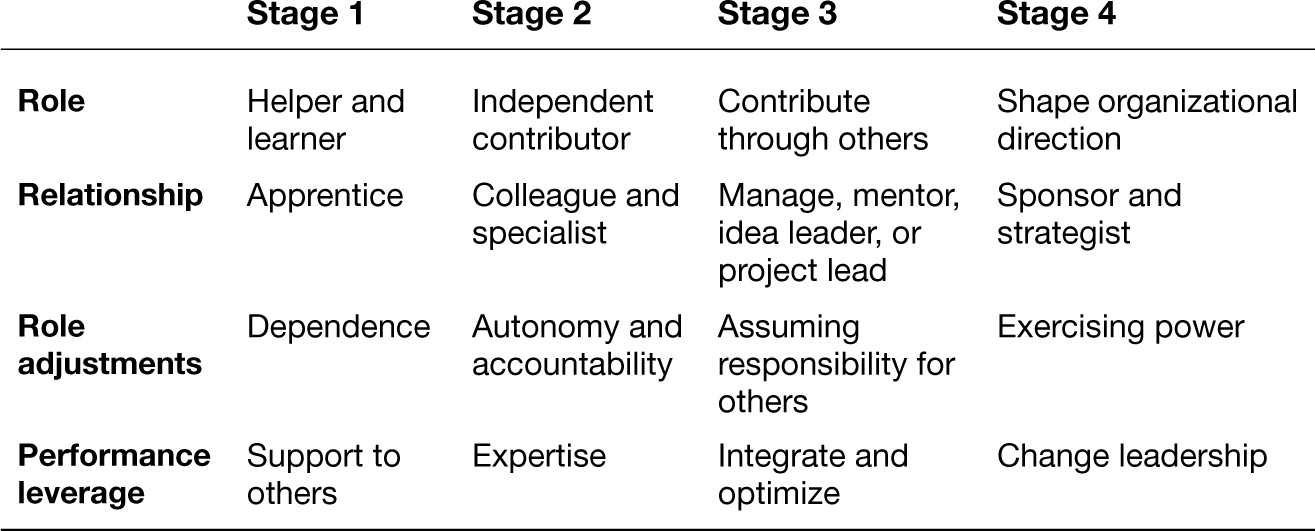

Determining the right mix of career stages for your agile talent is a five-step process. Tool 5-2 provides a simple framework of the career stages. It describes the role played in each stage, the individual’s relationship to colleagues, what the role demands, and the performance leverage (how individuals at each stage deliver value).

With this tool in hand, take the following steps:

- Review the career stages. After getting an overview, you might find it helpful to identify individuals who are well known and who are good representatives of different stages. Giving individuals models to relate to, that make the career stages real, is a useful first step.

- Sort your current resources—both internal and external, on contract or advising—by career stage. For those moving between stages, indicate whether they have progressed sufficiently to perform at the higher stage.

- Define your organization’s optimal mix by career stage today and a year or two ahead: what mix of stages is required to do the work of the function or technical team or organization at a high-performing level? And, based on this assessment, identify them. Defining these mixes also defines the gap between the “what is” and the “what should be.”

- Determine the plan to close the gap. Here is where the organization returns to the strategic resourcing matrix we described in chapter 3 and provided in figure 3-1. What mix of internal staff and agile talent will provide the organization with the greatest opportunity to improve effectiveness and efficiency? What are the opportunities and prerequisites for building, buying, or renting expertise?

- Finally, take action to implement the plan. The actions broadly fit into three categories. First, where will a change in the resourcing mix enable the organization to take greater advantage of agile resourcing? Use the strategic resourcing matrix from figure 3-1 to make this determination. Second, how should the composition of internal resources be modified to complement agile talent resourcing plans? For example, if project managers don’t have stage 3 skills, how can the organization accelerate their development and competence to make the best use of contractors and other externals? Third, be clear and insistent about the stage mix of external resources needed to deliver the value required and put in place a process of performance review and feedback to ensure the requirements are met.

TOOL 5-2

Determining the right mix of stages among externals and internals on your team

See the text for how to use this tool.

Summary

There are a variety of applications of the career stages; we have only reviewed a few in this chapter. The most fundamental is the help that the career-stages approach provides in answering the question “What do I need to do to be seen as a strong performer?” In a study we completed several years ago, only 43 percent of the technical professionals we polled could confidently respond positively to the question “I know what I need to do to be successful in this organization.” A good working knowledge of the career stages by both managers and individuals increased this number to 80 percent.

We have examined how agile talent is best attracted, recruited, developed, and engaged, whether the experts are internal staff or external partners. In the next chapter, we look at practical methods of increasing the productivity of external agile talent, setting up and aligning responsibilities within the mixed team, and more fully engaging externals who are working in your organization.