7

Leading Agile Talent

Understanding the Skills You Need and How to Apply Them

As with success in meeting other strategic changes, the effective tapping of agile talent depends on the quality of leadership. Unless leaders embrace the opportunity for, and tactics of, greater talent agility and actively sponsor the shift, employees and lower-level managers are likely to be resistant. Where leaders do not take the actions needed to effectively implement agile talent, this talent will not deliver the benefits.

On a recent trip to Kyoto, one of us learned about a unique sixteenth-century security system at Nijo Castle. Called the nightingale floor, it was designed to “chirp” when walked upon, alerting the guards if an intruder was sneaking in.

With its defensive orientation, the nightingale floor is a fitting metaphor for how frequently leaders and organizations are inclined to see agile talent in us-versus-them terms. Rather than view agile talent as partners and a valued extension or reinforcement of internal capability, organizations too often view external talent with suspicion, or as a necessary but lamentable evil.

With this attitude, the organization is disadvantaged in multiple ways: disengaged agile talent wastes the time and effort of both the externals and the internal staff working with it or depending on it. The often-costly investment of working with external talent is sub-optimized. The organization is inattentive to good counsel and best practices. And over time, the organization may develop a reputation for being poor clients or for establishing poor working relations with external talent. Such a reputation makes agile talent less engaged with the organization and consequently less effective. With less effective external resources, the organization feels less compelled to engage its outside talent, and a downward spiral of poor performance can ensue.

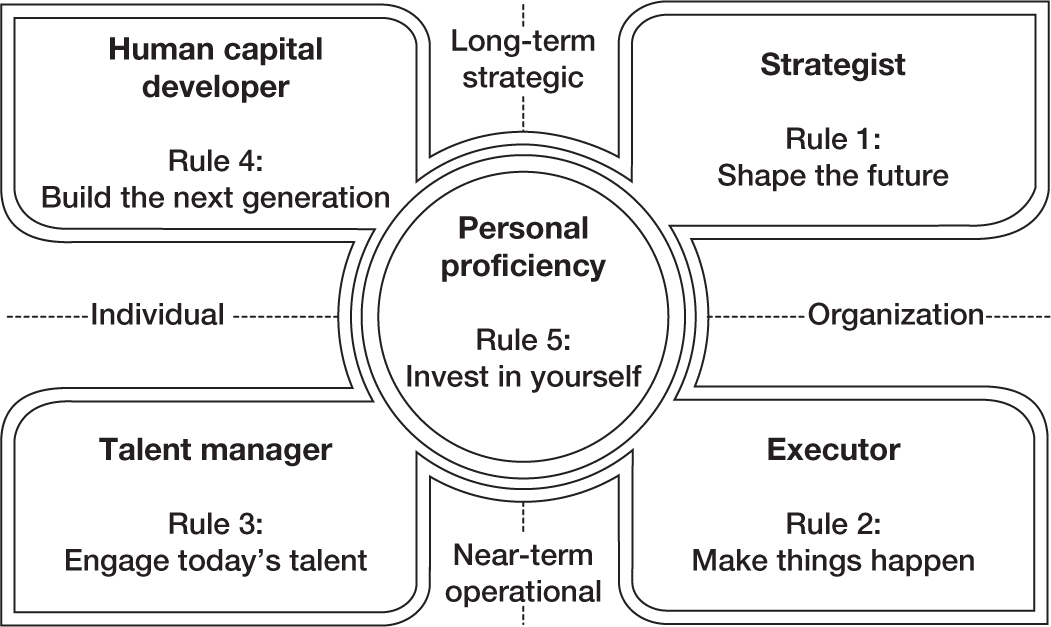

The Leadership Code

What are the skills required by the leaders of organizations seeking the benefits of agile talent and expanding their use of cloud resourcing? Our work in leadership development is helpful in this context. Faced with the incredible volume of information about leadership (over 475 million separate entries in a Google search), we honed in on the opinions of experts in the field who had earned a reputation for their work in leaders and leadership. In our discussions with them, we focused on two fundamental questions:

- What percentage of effective leadership is described similarly across the range of leadership research and theories?

- If there are common skill sets that all leaders must master to be an effective leader, regardless of industry (or not-for-profit status), what are these skills?

FIGURE 7-1

The leadership code: five foundational competencies

Source: Dave Ulrich, Norm Smallwood, and Kate Sweetman, The Leadership Code: Five Rules to Lead By (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2008), 14.

Our study found that 60 to 70 percent of good leadership is similarly described by theorists and researchers. When asked to describe the 60 to 70 percent, the respondents showed an exceedingly high degree of convergence in concept, regardless of small differences in nuance and language. We call these basics the leadership code, which we examined in detail in The Leadership Code: Five Rules to Lead By.1 Figure 7-1 presents a visual framework of the five rules of leadership constituting the code.

Strategist: Shape the Future

Strategists answer the question “Where are we going?” and ensure that the workforce—both internal and external—understands the goals of the organization, the workforce’s contribution to those goals, and the importance of people’s effort and performance to customers, investors and other stakeholders. Strategists envision the possibilities, define the strategy, build internal and external support, ensure critical inputs (investments, skills), build the organization, devise the change plan, and engage both internal and external resources in owning and achieving the goals. In short, strategists position their organization for both current and future success.

Executor: Make Things Happen

The executor competence complements the strategist: executors answer the question “How will we make sure we get to where we are going?” They translate strategy into a plan of action, make change happen, and ensure a high-performing culture that is consistent with the organization’s goals, establishes accountability, supports innovation, and puts the right people together in the right teams with a clear focus. Leaders operating as executors establish the organizational and performance disciplines that convert plans into programs of action and that convert action into results.

Talent Manager: Engage Today’s Talent

Effective leaders develop and engage talent: they identify the skills needed for high performance, and they encourage, develop, and motivate people—internal and external—to feel ownership for the organization’s goals. Talent managers ensure that the competencies required for success are in place, accessible, and delivered effectively and cost- and time-efficiently. To engage people, talent managers appropriately deploy both technical and interpersonal skills and build enthusiasm through communication and involvement. As performance disciplinarians, talent managers are unafraid to take prompt action in response to poor performance, but they equally act as coaches and mentors, and investors in high performance.

Human Capital Developer: Build the Next Generation

Talent managers focus on current goals and challenges and the agile talent required to overcome these challenges. But industries change and a key task of effective leaders is to be thoughtfully aware of new performance requirements requiring new capabilities. For example, Uber senior leaders recognize that the next generation of their business is likely to involve a massively disruptive shift from driver to autonomous (or self-driving) taxis. Consequently, they established a relationship with Carnegie Mellon University’s National Robotics Engineering Center, the same center that is providing innovative robotics technology to the US military.

Uber leaders provide a helpful example of the fourth leader discipline: human capital developers. This leadership competency ensures that the leaders’ organization has the skills required for future performance as well as for responding to current needs. Human capital developers enable the organization to develop a people plan that defines the skills and perspectives required for continuing achievement as the organization and its strategic goals evolve over time. In doing so, leaders also demonstrate creative, innovative, and unexpected solutions. For example, JP Morgan Chase has brought into the bank young PhD mathematicians and physicists, as well as finance experts, to provide analytic support to its equity and bond traders.

Over the last several years, we’ve collected data from thousands of managers through a 360-degree survey to assess leadership code competence. The pattern in our results is clear and illuminating: without doubt, the domain of human capital development has the lowest competence score for leaders across every industry and every region (table 7-1).

TABLE 7-1

Competence of business leaders in foundational disciplines

| Leadership domain | Mean competence score* |

|---|---|

| Strategist | 3.7 |

| Executor | 3.7 |

| Talent manager | 3.7 |

| Human capital developer | 3.5 |

| Personal proficiency | 3.8 |

Source: RBL survey.

*Mean self-evaluation score of over 20,000 managers participating in a 360-degree survey about their competence in various leadership domains. Participants were from diverse industries and various geographic regions globally. Score is on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = poor performance and 5 = outstanding performance.

The relevance of this to agile talent is obvious. The premise of agile talent is that as capability requirements change in response to technology or competitive changes or the performance expectations of investors and regulators, leaders must anticipate and respond to these needs. Leadership skill as a human capital developer is critical to this combination of insight and action. But as we will soon point out, all of the leadership disciplines contribute to success in utilizing agile talent for the benefit of the organization.

Personal Proficiency: Invest in Yourself

A fifth leadership discipline is personal proficiency. Effective leaders are good models. Strong leaders inspire loyalty and goodwill in others because they themselves act with integrity and trustworthiness. They provide a model of appropriate behavior to others—at all levels of the organization, as well as to agile talent operating on behalf of the organization—and deal with difficult situations in an open and evenhanded way. Other qualities they exemplify include clear thinking, self-insight, stress management, modeling lifelong learning, and taking care of oneself physically.

How Strong Leaders Make Agile Talent Work

What are the important leadership actions that lead to success in agile talent? As outlined earlier, executives described the top-five reasons for utilizing expert talent:

- Increase availability of expertise

- Reduce cost

- Avoid adding permanent headcount

- Increase the speed of getting things done

- Externals challenge our thinking and assumptions

Executives have busy calendars and they face many issues and people competing for their time and attention. What are the high-value ways that leaders apply the leadership code to the effective use of agile talent? We focus on all of the five leadership dimensions.

Strategist: Providing the Sponsorship Needed

Effective strategists understand the impact of a few critical leader behaviors on the performance of external resources. In this regard, there is no more crucial area than ensuring the right level and kind of sponsorship.

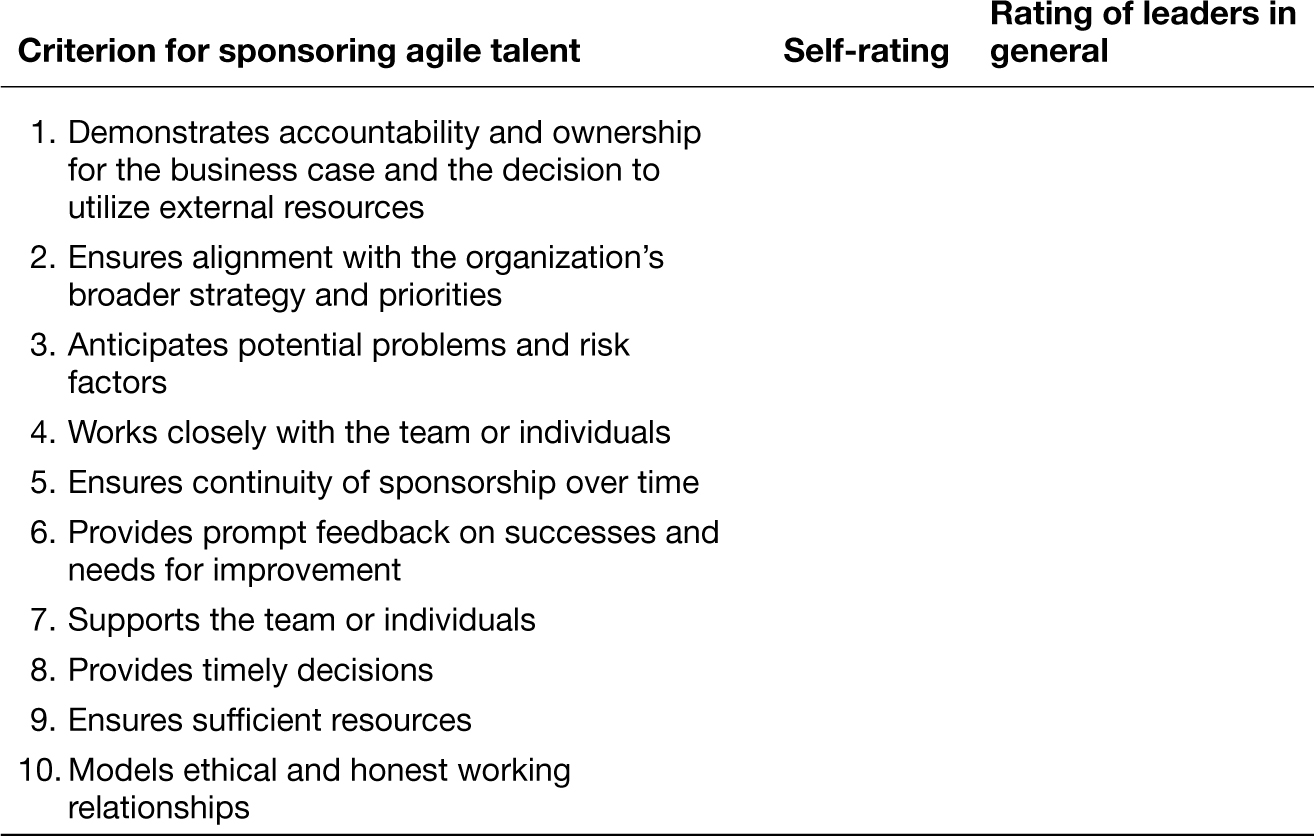

In an earlier chapter, we reported an interesting finding from our survey of executives: slightly above half of responding leaders described their organization as effective in ensuring that the work of external resources was appropriately sponsored. This is good news for the satisfied half of the executives and worrisome for the remaining ones, who expressed concern or criticism. What does good sponsorship look like? We provide a number of key criteria in tool 7-1.

TOOL 7-1

How well do you sponsor agile talent?

Rate your organization on each criterion on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = almost never, and 5 = almost always. Then rate where you think other leaders in your organization stand on the same criteria.

After you have filled in tool 7-1, notice how the scores are distributed:

- Does the leadership of your organization provide a high-enough level of sponsorship for agile talent to deliver real value consistently?

- Are you satisfied with the quality of your sponsorship or that of your immediate boss?

If the answer to either or both questions is no, consider these additional questions:

Executor: Good Leaders Plan and Clear the Way

If a key deliverable of the strategist is providing the required sponsorship, the equivalent executor competency is the leader’s role in clearing the way for the organization to achieve high performance. Steve Jobs was once asked who best exemplified what it takes for a business to be successful. He replied, “My model for business is the Beatles. They were four guys who kept each other’s negative tendencies in check. They balanced each other, and the total was greater than the sum of the parts. That’s how I see business: great things in business are never done by one person, they’re done by a team of people.”2 Jobs’s comment points out that putting the right people together with the right skills to achieve a clear and common goal is at the heart of execution. When agile talent is added to the mix, the way that leaders set goals, review performance, and build strong teams becomes even more important. The inclusion of agile talent in an organization raises an additional complexity: the need to build effective relationships between internal and external resources.

When the respondents in our survey were asked how well their organization brings together internal and external resources in common cause, we found an interesting mix. Slightly less than half of the executives in our study report that their organization does a good job of helping external resources build the right internal relationships to succeed. Another 30 percent are neutral, describing their organization as neither strong nor weak; 20 percent of executives are highly critical.

Google is a good example of an organization working hard to improve executor skills in its organization. Google’s Project Oxygen, currently under way as a key research project in HR, focuses on what it takes to build and lead a great team. For example, Google has identified the importance of pairing challenging project goals with short time horizons.

IBM took a different tack in helping its software development managers be stronger team-building executors and focused on the career-stages research reviewed earlier. The company found that high-performing teams had more than the technical expertise required. The teams also had the right combination of career stages: namely, stage 1 and 2 individuals responsible for doing the work and stage 3 professionals and managers who managed work streams, coordinated the work of professionals, integrated their work with the efforts of other teams, and mentored and coached individuals. Stage 4 professionals, in turn, ensured that the teams had the resources and other support they needed and, when necessary, protected the team from interruption.

Another critical element in effective internal-external teamwork is simply time together. Katzenbach and Smith describe the importance of time for teamwork in his research on high-performing teams. A good example of making time is the Zappos quarterly “all-hands meeting,” which combines information about company performance, team-building activities that include both internal and external talent, and inspirational guest speakers. Zappos also supports internal-external teamwork through its blog Zappos Insights as a way to keep people informed about performance and company events and activities. The blog is a powerful and simple way to engage external agile talent.

Ongoing performance feedback is another effective tool for effective internal-external teamwork. Our pilot study asked executives to describe how effective their organizations were in providing external resources with regular feedback on their contribution. We found a very similar trend to the findings for internal-external relationships: approximately 50 percent of executives report that their organizations provide externals with timely feedback on performance, 30 percent were neutral in their ratings, and 20 percent see a need for improvement.

Finally, executors are mindful of the need for ongoing improvement in the effectiveness of their organizations and what can be improved through tools like after-action review. As described earlier, after-action reviews are a US military tool created to improve learning from both successful projects and failures. We asked executives, “How well does the organization use after-action review to learn from the actions and results of external experts?” and found that only a third of executives were positive in their ratings of after-action review frequency and quality. An equal segment of executives was less sanguine, believing that their organization could use after-action review more often and effectively.

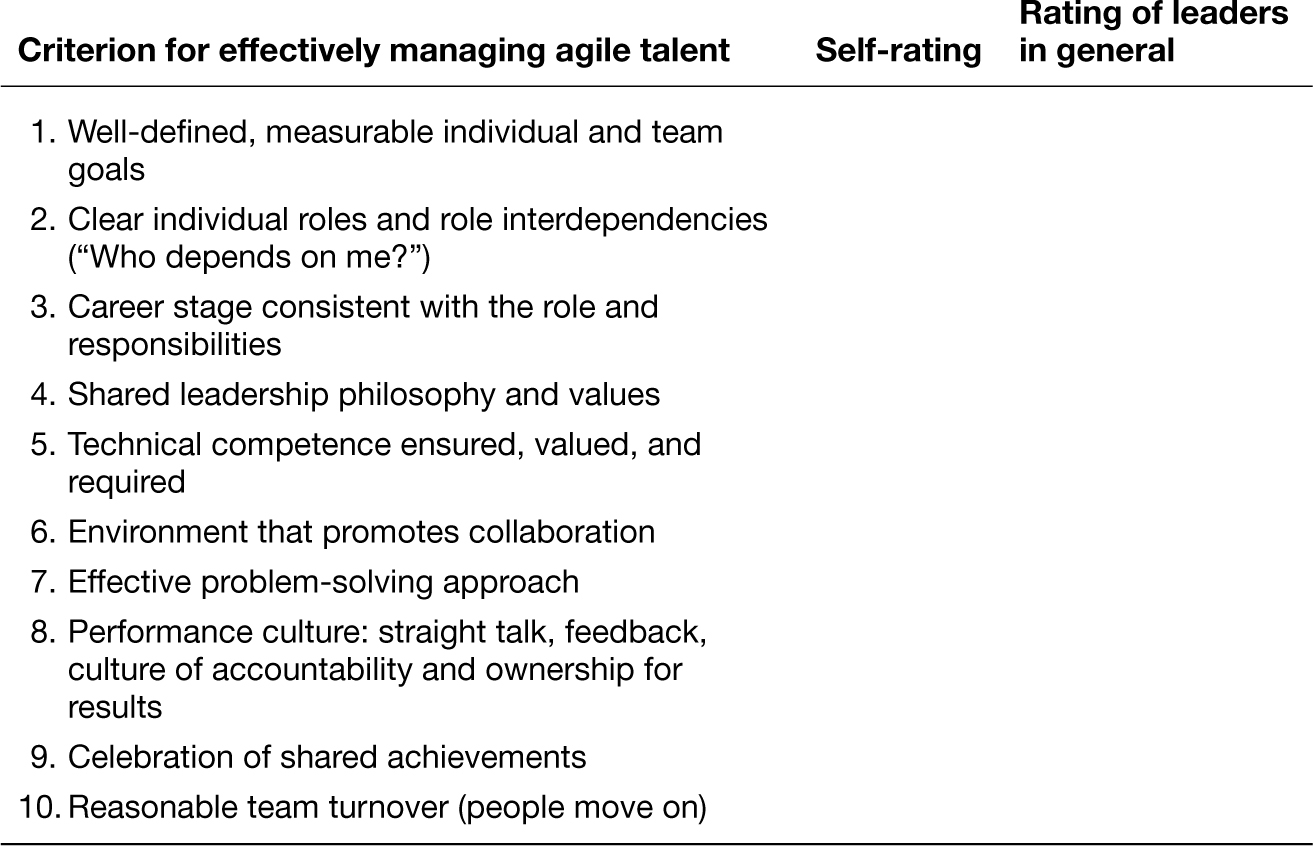

Talent Manager: Matchmaker for Development

The talent management aspect of good leadership plays an obviously critical role in agile talent. This manager ensures that the organization has the skills required to achieve today’s goals, overcome performance challenges, and the systems in place to continue to sharpen employees’ competencies and contribution.

Talent management starts with recognition of the skill set and competency mix required to achieve the team or organization’s goals. Good leaders use a systematic approach to decide how to best resource an initiative. They understand the relative importance of a given task over other priorities and consider alternative resourcing approaches in light of short- and long-term benefits. They use a version of the strategic resourcing matrix to decide when it makes sense to own resources and when it makes more sense to rent or hire them, with the expectation that the agile talent is excited by a project opportunity but not interested in becoming a long-term employee. Mark Zuckerberg describes his philosophy of resourcing at Facebook as follows: “We want Facebook to be one of the best places people can go to learn how to build stuff. If you want to build a company, nothing is better than jumping in and trying to build one. But Facebook is also great for entrepreneurs/hackers. If people want to come for a few years and move on and build something great, that’s something we’re proud of.”3

A strong talent manager recognizes that selecting project leaders to work with or to oversee the external talent is an important decision. A recent study pointed out that among research labs in R&D organizations, the talent mix is the principal determinant of lab productivity.4 When external experts are asked to describe great internal project managers with whom they have worked, they consistently report the following qualities listed in tool 7-2. You can use this tool to consider how well your organization applies the skills of talent manager to external resources and how well you do so yourself.

TOOL 7-2

How well does your organization manage agile talent?

Rate your organization on each criterion on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 = almost never, and 5 = almost always. Then rate where you think other leaders in your organization stand on the same criteria.

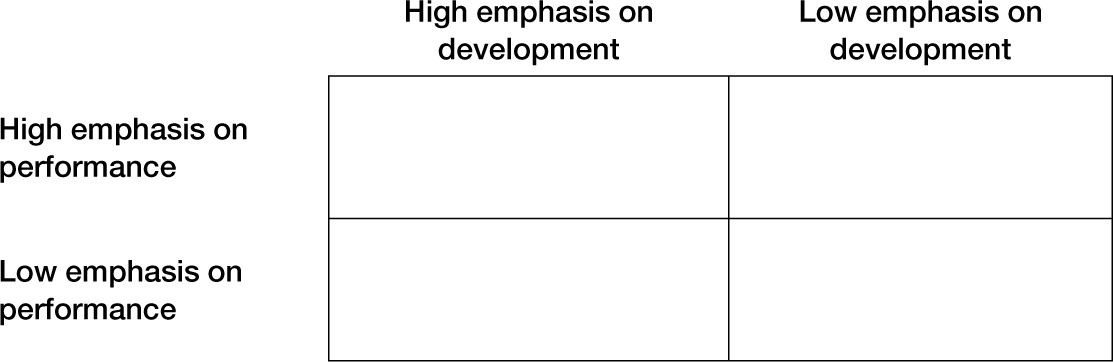

Using a matrix like the one in tool 7-3 helps leaders select project managers who will do a good job of managing externals and will grow professionally as a result of the experience. The optimal condition is the top left box: a dual emphasis on both performance and development. And this in turn requires that the organization have a process for assessing project management aptitude and performance and for supporting the development of project management competence.

TOOL 7-3

Determining a prospective talent manager’s emphasis in working with agile talent

Check which box in the matrix best represents the aptitude of the talent manager you are considering for developing and supporting your agile talent.

Effective talent managers also build effective systems of development that link internal and external agile talent. Many organizations bring in expert externals, typically stage 3 or 4, to work as coaches for their younger leaders or for professionals that have run into performance difficulty. Norwegian multinational oil and gas company Statoil took this concept to the next level by creating “schools” in areas like oil-field project management, where leaders were explicitly connected to external experts in the area through educational opportunity and coaching. For Statoil, this was a critical initiative: despite the typically high level of Norwegian technical professionalism, the extreme, harsh climate of working in the North Sea and the Arctic Circle challenged Statoil to step up its effectiveness. A similar approach was used to build skills in other critical areas such as HR management. By combining coaching with education and work on key priorities, Statoil developed a unique cadre of talent in multiple areas.

Human Capital Developer: Build Ongoing Competence

Companies are utilizing agile talent because it offers them another route to the expertise they need to compete, perform, and grow. Partnerships with third-party agile talent continue to expand because organizations benefit from the access to expertise that enables them to increase strategic organizational capability and to deliver these capabilities more quickly, effectively, and cost-efficiently. We have described the implications of the strategist and executor roles of the leadership code, how organizations improve the use and performance of external experts. The role of human capital developer is particularly important because this aspect of good leadership prepares the organization for the future and is most likely to utilize agile, external talent.

The Leadership Code describes a number of skills that are at the heart of leadership competence in this area.5 From the perspective of agile talent, effective leaders demonstrate excellence in human capital development when they think and act from the outside in.

The first test in outside-in thinking is what we call mapping the workforce. Mapping the workforce is another way of asking, Do we have the skills we will need to achieve our goals in the foreseeable future? In chapter 2, we described how organizations best assess the opportunity for agile talent. Uber, we mentioned, demonstrated this capability by recognizing that its strategy was linked longer term to self-driving cars and that robotics was going to be a critical area of technical expertise. Interestingly, Uber later ended up hiring the entire team, thus complicating efforts by other firms to make use of the Carnegie Mellon capability. By contrast, GoPro, the wearable-camera company, recently expanded its strategic vision to include other wearable technology. In this vein, it is working with a range of business and technical consultants in the fashion industry and with several joint ventures.

The agile-talent twist on mapping the workforce is that a good map includes both internal and external players. A leader who thinks of only internal resources and full-time employees has limited his or her resourcing options.

Mapping the workforce is the opener, but strong human capital developers also understand the importance of the organization’s reputation as an employer of agile talent. Earlier, we discussed the importance of employer branding to the attraction and retention of external as well as internal agile talent. Talented external experts are typically in demand, have more opportunity than they can handle, and are disposed to work in organizations that value them and their contribution.

Our work with Driscoll’s reinforces this point. As we mentioned, the leaders invested the necessary time in agile-talent orientation, ensuring that the external team understood and supported the company’s vision and values.

As we said earlier, the leadership of Driscoll’s recognized that our knowledge as leadership consultants and our commitment to its strategy and culture made a difference. By sharing the history and importance of the company vision and way of working, and by requiring that deliverables be framed in terms of the mission and values, the company made the external resources feel and act as partners rather than a pair of hands. Do we have evidence that this investment of time made a substantive difference? No. But by making their success our success, Driscoll’s certainly raised the level of consultant ownership and pride.

Human capital developers take seriously their responsibility as skill and career developers and extend this responsibility to the agile talent with whom they work. For example, Google is broadly committed to publishing the results of innovative internal and external work as long as there is no strategy impairment. For external resources, this commitment is significant. Management and technical consultants often rely on the publicity surrounding their work as a means of gaining future project opportunities and building their reputation for expertise.

Human capital developers take an interest in the careers and development of external resources. Leaders have always been expected to mentor and coach internal employees, but cloud-resourcing logic invites leaders to also be open to doing the same thing for external talent as well. The very process of supporting a career through conversation and the demonstration of active interest builds engagement and improves the relationship.

Smart leaders also understand that today’s consultant may be tomorrow’s internal employee or leader. External agile talent has long considered the move from consultancy to client organization as an attractive career path. Leaders considering external experts have the benefit of seeing them in action. A thoughtful leader sees this talent as an important source of experienced recruits.

Outside-in thinking about emerging skills and needed capabilities encourages leaders to be active networkers. Smart leaders are eager to learn how other organizations are approaching opportunity or responding to similar challenges. External resources are an excellent source of industry insight and innovation. For example, we were recently asked by the chief HR officer of Hewlett-Packard to give her team a presentation on strategic talent issues facing high-technology companies. Similarly, Bill Allen, head of HR at Macy’s, made it a point to engage us in a series of discussions about the future of HR with his top managers before initiating an HR organizational transformation. And Pat Hedley, a managing director of the private equity giant General Atlantic, agreed to chair a newly formed private-equity HR association to stay up-to-date on HR trends in her industry.

More fundamentally, leaders who operate from the outside-in tend to build inclusive rather than exclusive cultures. We talked earlier about the importance of engaging external resources from day one and the value of treating this important element of your overall workforce with respect and trust rather than suspicion. A leader who encourages networks and a broad set of external relationships is more likely to appreciate what it takes for agile talent to learn how to perform in a new organizational environment. And the leader is more likely to provide a sufficient orientation and introductions to facilitate the individual’s success. In a savvy leader’s view, the individual is a part of the organization’s larger performance system rather than a temporary intruder.

Effective human capital developers also invest in giving their employees outside experiences, so that the workers are sensitive to other cultures and organizational environments and are more likely to welcome and cooperate with external resources. The great global consumer products company P&G invests significantly in training and development because leaders over multiple generations of management have found that employees who have these outside experiences are more collaborative, team oriented, and open to other points of view.

We think a similar result occurs when companies invest time in building relationships between internal and external experts. In the Gallup survey of engagement, the most committed people have work relationships that matter to them.6 Organizations can take advantage of this association between meaningful work and engagement by offering its workers appropriate assignments and by building communities of practice that support diversity or technical skills. These communities operate most effectively when they are inclusive, not divisive. Leaders need to ensure that external talent is both welcomed into these communities and expected to contribute best practices and innovative ways of working as a condition of employment. Strong networks lead to faster learning and more collaboration.

Personal Proficiency Ties It All Together

Unlike the preceding leadership competencies, personal proficiency is about the model a leader presents through his or her actions, choices, way of solving problems, and values. We’ve always enjoyed the question, very fitting in the context of personal proficiency, “Why would anyone want to be led by you?” This question has special meaning for agile talent.

A personally proficient leader expresses his or her humanity in dealings with agile talent. These leaders understand that beyond the technical or functional requirements of the work itself, the most difficult aspects of agile-talent work are often personal and interpersonal. Operating as a consultant, an external adviser, a freelance software architect, or any other external expert can be a lonely existence. And it is often a challenging one: a person faces the loneliness of working in a new organization, the stresses of coming and going on assignment from workplace to workplace, getting to know and work with new people and their individuality, and learning to operate effectively in new organizational environments, each with their own unique culture.

When all is said and done, effective leadership is an act of generosity. Good leaders are remembered as being generous with their time, hospitable to colleagues and guests, and willing mentors. All of these qualities are as important to external talent as they are to internal talent. The leadership qualities described by the personal proficiency competency create high-performance environments for part-time and temporary as well as permanent staff.

Summary

This chapter reviewed how the actions and skills of leaders have a significant impact on the effectiveness of agile talent. Leaders who have the competencies of the leadership code are more able to build high-performance organizations and create an environment of inclusion that attracts and retains agile talent—whether the talent is there for a gig, a project, or a career.

In the last several chapters, we’ve described the alignment challenge in getting the most from agile talent. The results of our survey suggest that the skills required by leaders who wish to make the most of agile-talent resourcing are often well in place. This is good news. Many of the executives report positively on their organization’s efforts to set appropriate goals, anticipate potential problems and difficulties, establish relationships between internal staff and external talent, and provide helpful feedback and communication updates. We also found that consistently between 25 and 35 percent of executives are less fulsome in their assessments, are more critical of their organization’s handling of external resources, and asserted that their organizations had both the opportunity and the need to improve.

In the next chapter, we turn from aligning the organization to leading the change, the next step in securing agile talent.