8

Leading the Change

Driving Innovation in How Your Organization Manages Talent

We know the challenges of agile talent are on the rise.1 According to Plunkett Research, global revenues for established consultancies (combining HR, IT, strategy, operations, and business advisory services) totaled $431 billion in 2014, up 4 percent from 2013.2 That agile talent is a global phenomenon is shown in the fact that the US share of these revenues is $180 billion, less than half the global total. The data only includes revenue figures reported by consulting firms with more than one person. Plunkett mentions the one-person businesses in the summary to its 2014 research report: “In contrast to the size and infrastructure of the leading management consulting companies, a large portion of the industry is comprised of very small companies—in many cases these are one-person shops, perhaps operating from a spare bedroom at home. This part of the business has grown rapidly.”3

Whether agile talent is a firm or an individual, the challenge of change is always significant, and particularly so for cloud resourcing. In this chapter, we focus on a framework to guide agile-talent planning, we identify key threats to successful change, and we offer readers several tools and techniques that provide practical guidance during change management.

Variations on Agile Talent

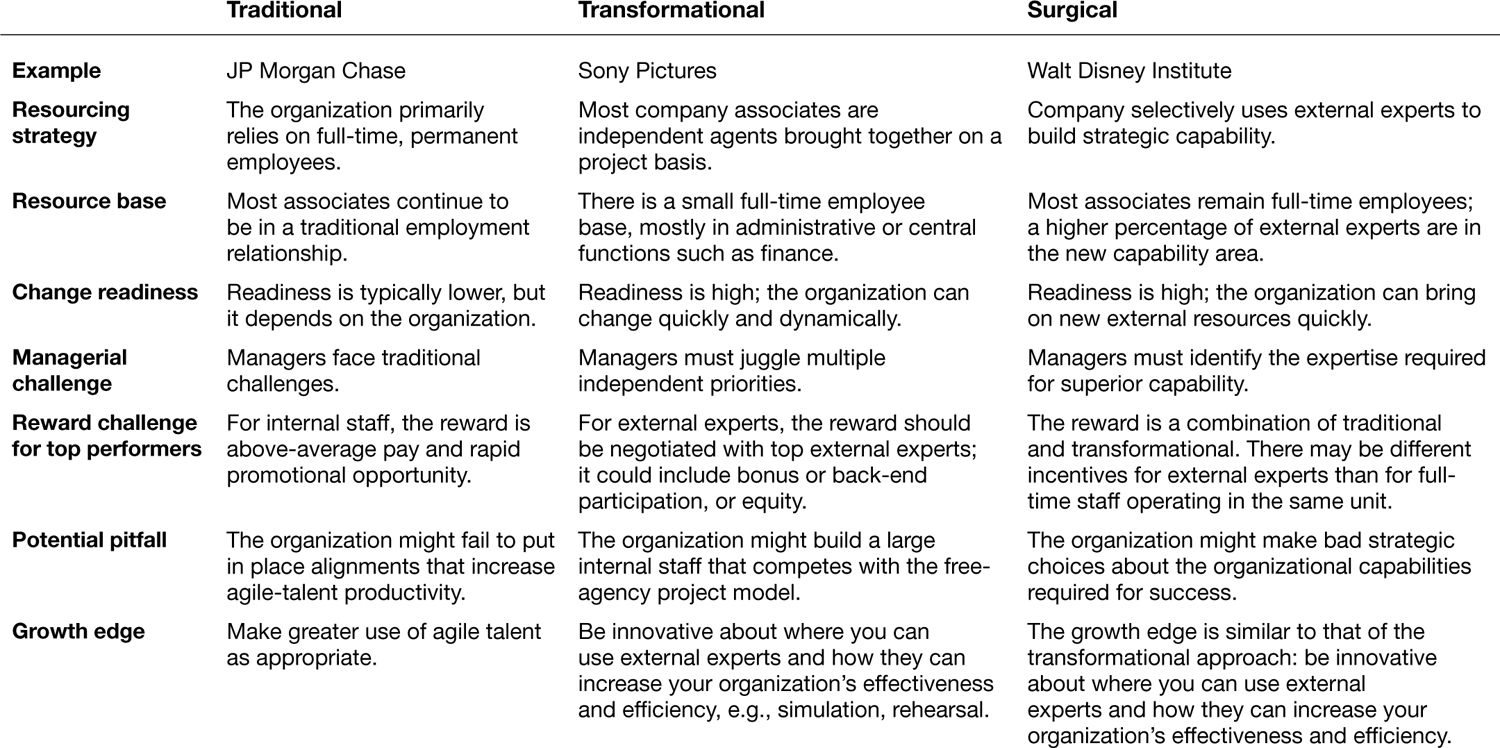

In a global economy embracing agile talent, it makes sense that organizations are taking different paths in gaining the advantage of what it offers. As described earlier, there are three alternative paths a company can take.

The Traditional Path

The traditional path is the null version of agile talent, and it is probably the situation in which most organizations find themselves. In this approach, leaders of traditionally structured and managed organizations choose to take greater advantage of what these new opportunities offer on an exception basis. The traditional version of agile talent requires the least change; the dominant logic of strategy and organization is that a significant majority of work will continue to be performed by full-time, permanent employees and that external experts will primarily be drawn into work on an exception basis, where their skills are strategically important and generally available. “Rent the best, and ensure success” is the mantra of this approach. We believe that for the foreseeable future, the traditional approach is likely to continue to be the most prevalent version of agile talent.

The Transformational Path

Organizations that depend on virtual organization structures are uncommon, but there are a few. Industries such as motion pictures and other entertainment offer a glimpse of the possibilities of working with the agile talent of the future. For example, many of today’s movies are funded by a myriad of production companies. And in the movie credits, it’s not unusual to see scores of supporting firms that have provided services from health and safety for the cast and crew to leased lighting equipment.

Software start-ups in Silicon Valley are the leading industry that is comfortable with the transformational approach. Andreesen Horowitz, a well-known investment firm, trumpets its competitive edge as the ability to connect start-up companies to the company’s unique agile-talent network. And described earlier, a growing number of agile-talent organizations operate on a community model where independent experts come together from across independent firms to work on joint projects, and the firm provides basic administrative services. Cordence, now a community of over two thousand consultants, enjoys aggregate revenues of over $600 million. Interestingly, Cordence consultants are generally happier with their organization than are most consultants.4

The Surgical Capability Growth Path

This third category, surgical capability growth, describes organizations that choose to take a more selective, or surgical approach, to the use of agile talent. In this case, agile talent is applied to accelerate capability development or change. The surgical path is an intermediate state between traditional and transformational approaches to agile talent. For example, as Michael Lewis observes in his book Flash Boys, as high-speed trading became a critical capability for brokerage firms, the industry could not find sufficient full-time talent.5 There were few technical experts who had the competence to create the new equity trading platforms and private exchanges that were required to meet the expansion of the business. To remain competitive in this new world, firms relied on agile talent and other resourcing arrangements to quickly grow their capability. For example, the Disney Institute grew over time, but early in its history, it brought in a core group of agile talent, including consultants and executive education specialists, to power its early growth and development.

![]()

Table 8-1 presents some advantages and disadvantages of the three approaches to agile talent and gives some examples of companies using each one. Despite the distinctions in these approaches, we also know that they intersect. In the movie industry, a transformational catalyst, the breakup of the so-called Hollywood studio system in the early 1950s and the introduction of independent production companies, shifted the use of agile talent from traditional to transformational. As the producer role gained in influence, producers developed their own virtual teams, which they regularly brought together to plan, make, and distribute their movies. Relationships between the producers and their favorite directors, cast, and crew created the modern movie production: an intense, high-performing cast with some individuals involved for years and others for only months or weeks.

The path to transformational change in agile talent is incremental; organizations shift from a traditional resourcing format to the intermediate state we’ve described as surgical capability growth. Few organizations outside of industries like finance and entertainment have gone all the way to transformation, and we believe that most organizations may, in fact, continue to operate fundamentally in a traditional manner. But clearly, global experience in business process outsourcing, together with increased availability of agile talent in developing countries, has led organizational leaders to feel more confident and potentially more adventurous about broadening and deepening their use of external resourcing.

The Challenge of Change

Determining the depth and focus of involvement in agile talent is a critical first step for any leader. Whether the organization is incrementally upping its involvement in agile talent, tapping the cloud for help quickly and powerfully building specific capability, or aiming over time to fundamentally transform the way the organization chooses to resource work, there is the practical challenge of managing change. In prior chapters, we have described some of the specific areas where change is required or beneficial. In this chapter, we provide a more integrative view of how an organization should approach the change process. And we show how cultural issues that arise in the course of change are best identified and addressed. Without question, leaders skilled at managing change—strategically and culturally—are more likely to achieve their goals.6

The Mind-Set of Successful Change

Imagine some great television interviewer in conversation with a trio of corporate chief executives, all of whom are reflecting on the shift in their organization’s resourcing philosophy. Although each of the three companies is in a different industry—banking, pharmaceuticals, and supply-chain logistics—and while each CEO is from a different continent, the companies clearly have some experiences in common.

Change Is Essential

This is the first point on which the CEOs agree. Change is essential as an ongoing response to shifting external and internal trends and circumstances. The leader’s role is to make sure the company is adapting—changing—in the best possible way. With respect to each company’s relationship to agile talent specifically, one of the most important messages a leader can send is the necessity of a more complex internal and external approach to staffing. We earlier pointed out that the leadership code factor where most managers are weakest is human capital developer, which requires understanding and meeting the talent needs of the organization in the future. In this context, it is crucial that leaders help their people understand why the organization is likely to depend more significantly on external resourcing, how a richer mix of resources will affect how the organization works, and what the shifts mean for full-time employees.

Change Is Hard

Change is resisted because it is hard. That’s the second conclusion of the CEOs in our pilot study. And change is hard because it is complex. We all know the statistic that 70 percent of change efforts do not achieve their goals; that observation, popularized by John Kotter, has been reported broadly.7 A second statistic makes this lack of successful change even more interesting and meaningful: 90 percent of change efforts began with a technically sound problem diagnosis and implementation plan.8 For many full-time employees, the increased use of agile talent implies greater hassle in dealing with people who are not “us” and whose loyalty and motivation are suspect. Full-time employees may fear that working with externals also means risk: risk of losing a job, changing a career, or moving to a new city.

We have seen this us-versus-them mentality play out in divisive ways in many organizations working with agile talent. The expert model in consulting exacerbates the problem and is difficult to change because most of the large firms are dependent on this business model. In the expert model, a large team of experts enters into your organization to solve a problem using their superior industry knowledge. The process of outside experts solving problems and then handing off the solution for implementation to internals creates resistance. To address this issue, we have utilized a more collaborative approach that is an alternative to the expert model. We call this approach the capability transfer model. Rather than sending in a large team of experts to solve the problem, we utilize a smaller team of more senior external experts who work with a combination of teams that are set up internally with the client to work with our agile talent. In the kind of work we do, these internal teams typically consist of a working team, seven to ten internal, high-potential influencers who go through a guided process with our senior external experts to create a roadmap for change. The roadmap includes a diagnostic and a plan for implementation. This team meets periodically with a second team of senior sponsor-level executives who provide guidance and support and who ultimately make decisions based on the recommendations of the working group and external talent. This process enables an everyone-is-us attitude rather than an us-versus-them climate. The process also accelerates change because the internals now really own the change.

Change Is Personal

Change is also hard because it’s personal. And for the architects of change, the decision makers, it’s often not personal. It’s what happens to people at lower levels of the organization. Take the case of Undercover Boss, an internationally franchised reality television show that places well-disguised company CEOs or other top leaders of organizations on the front lines of their own organization. The premise of the show works because we want executives to experience what the rest of us experience each day. And that is the challenge for leaders, to understand how the changes they are making will affect the work and motivation of the people who must implement the change. In every episode of Undercover Boss, the CEO of the company has some kind of epiphany about how ideas translated into action have an impact on people’s lives personally.

The capability transfer model of change also addresses the personal nature of change. In the expert model, a sophisticated resolution of the problem is handed off to internals for implementation. People resist change that they don’t own. They don’t own the expert model, because they have not been part of the change. They often believe that significant internal issues (politics, culture, and so on) have been missed or ignored by the outside experts, who focus primarily on a content resolution to whatever the challenge is. In the capability transfer model, the internal issues have been vetted by the internal working team and again by the sponsor teams. The process itself drives buy-in to change from the beginning.

Change Occurs at Multiple Levels

Finally, change follows its own path, despite our efforts to precisely engineer it. A timeless quote from the movie Jurassic Park illustrates this point: “If there’s one thing the history of evolution has taught us, it’s that life will not be contained. Life breaks free. It expands to new territories. It crashes through barriers painfully, maybe even dangerously, but—well, there it is.”9

Change is similar. And while it cannot be fully controlled, its unintended consequences can be anticipated. We think of four directions of change: what are the likely impacts on individuals, the team, the organization, and external stakeholders such as customers? Agile talent is likely to affect all of these levels, and a smart leadership team carefully considers both the probable and possible results of this change and takes proactive steps where possible.

The Pilot’s Checklist

A recent study of technology developments by Jim Johnson and colleagues found that initiatives were more likely to be successful when five factors were present:10

- EXECUTIVE SUPPORT: According to Johnson and his colleagues, the lack of executive support, or the wrong sponsorship, is the number one factor in project failure.

- USER INVOLVEMENT: A project will fail if it doesn’t meet the needs or expectations of its users or customers, and is more likely to fail when the users are not actively involved.

- EXPERIENCED PROJECT MANAGEMENT: Successful projects invariably have an experienced and talented project manager leading the work.

- CLEAR BUSINESS OBJECTIVES: Project success follows from setting the right objectives and ensuring that these objectives are clear, kept up front, and revisited frequently.

- MINIMIZED SCOPE CHANGE: Scope changes are as fraught in IT projects as in building construction. Effective project managers plan up front and keep scope changes to a minimum.

While Johnson and his colleague’s research is specific to IT project management, the findings are similar in concept to the pilot’s checklist, a change-management framework originally developed by Dave Ulrich, Steve Kerr, and others to support the GE Work-Out program. The pilot’s checklist is a tool that we have used in virtually every project we have undertaken at the RBL Group. The pilot’s checklist honors the tradition of an airplane pilot walking around the airplane, inspecting the aircraft’s flight-worthiness, before takeoff. The value of the checklist is that it ensures a sharp focus on the factors that will make or break the success of the pilot’s mission. So too with the change version of pilot’s checklist.

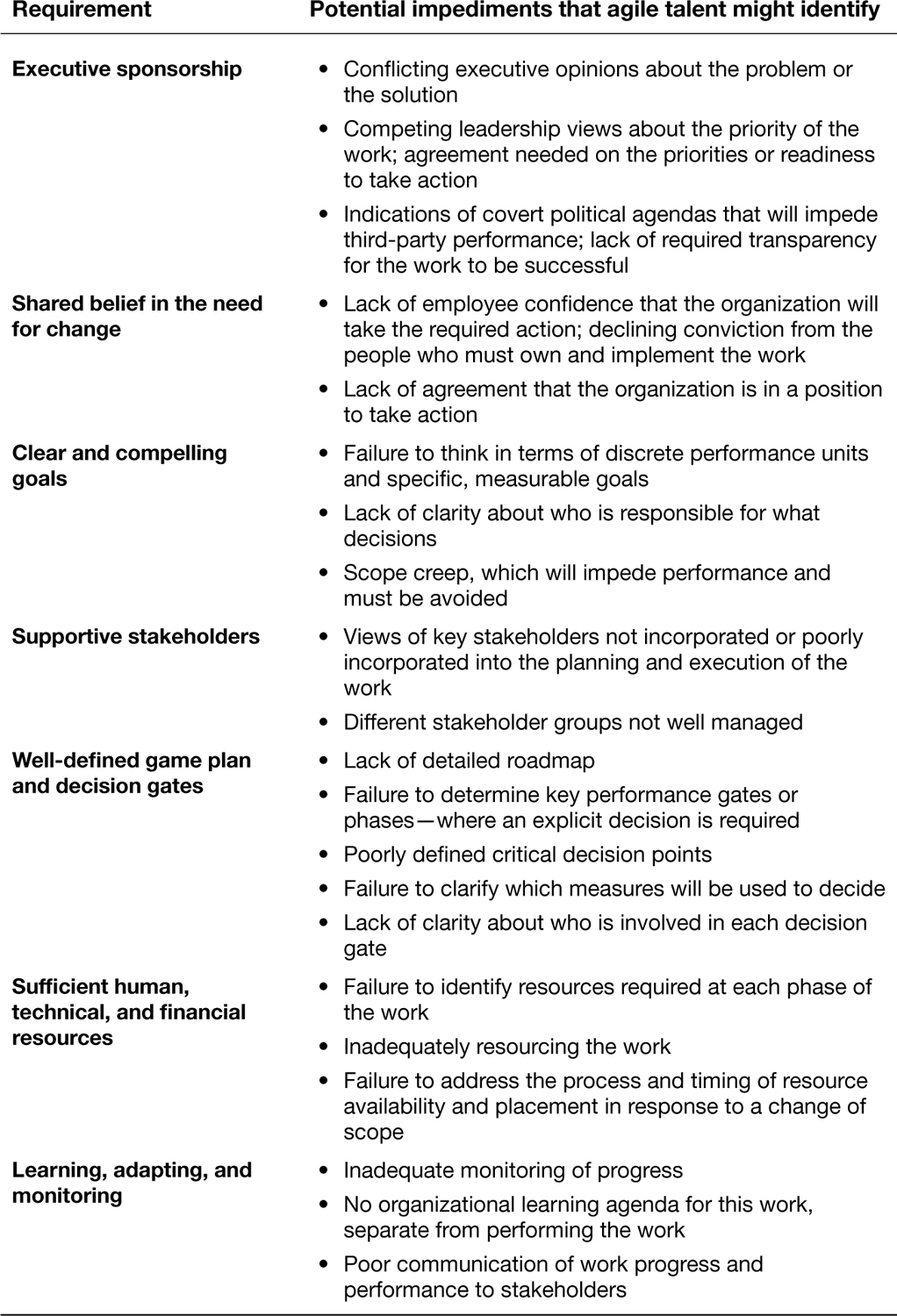

The pilot’s checklist identifies seven basic requirements for successful change management. The framework was initially created as a checklist to aid work teams addressing specific improvement projects to make sure that projects came in on time and on budget.

Tool 8-1 is a pilot’s checklist of requirements for a successful change venture. Read the requirements, keeping in mind a recent change effort at your organization. Then rate each requirement to identify what led to the success or failure of the change venture.

TOOL 8-1

The pilot’s checklist: identifying what leads to the success or failure of a change venture

Rate your organization on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 = disagree strongly, and 5 = agree strongly.

| Requirement | Rating |

|---|---|

| Executive sponsorship: We have clear and sufficient executive sponsorship and support. | |

| Shared belief in the need for change: There is sufficient broad agreement about the importance of the actions we are taking and why these actions are important and necessary to the organization. | |

| Clear and compelling goals: The goals are sufficiently clear and compelling to the individuals who are involved. | |

| Supportive stakeholders: The stakeholders for this change effort—individuals who must support or at least be non-antagonistic to the actions taken—are sufficiently supportive. | |

| Well-defined game plan and decision gates: The plan for this change effort is sufficiently detailed and defined, and the critical decisions are well enough identified. | |

| Sufficient human, technical, and financial resources: The critical and essential resources are in place or available as needed. | |

| Learning, adapting, and monitoring: A process is sufficiently in place for key actors and team members to review and assess progress, identify problems, and address impending issues. |

Involve the External Expert Community

Applying the pilot’s checklist is helpful in identifying what may get in the way of a viable plan to make greater use of agile talent. A not-very-well-used but potentially helpful source of information is the external experts who know your organization best. This agile talent may be able to provide unique insight on how the organization is unintentionally harming its efforts to drive greater cloud resourcing; for example, excessive payment delays may lead key agile talent to choose to work for a competitor. Table 8-2 suggests some potential impediments to success.

Dealing with Cultural Obstacles to Change

The pilot’s checklist offers a roadmap for effective change management, but it doesn’t explicitly address cultural obstacles to the change that leaders intend to put in place. All organizations have cultural elements that resist change; while some companies are more suspicious of external experts and resist using them, PepsiCo and Mars regularly work with a wide range of consultancies.

Some years ago, we created a tool to help leaders explicate the cultural barriers to change in their organizations. We called it the organization virus detector. For example, the HR leadership of TASC, a large high-tech contractor to the Pentagon, identified cultural factors as far more of a risk factor than financial or technical issues. As chief HR officer Jim Lawler put it at one of our meetings, “We have outstanding technical skill and strong financial backing. But, to grow, we need to develop a more agile culture.”

Test your organization’s cultural challenges to change. Bring a small group of your organization’s managers together to review and discuss an upcoming opportunity to involve external experts in an important project or initiative. Ask each manager to identify what he or she sees as three of the critical cultural obstacles to the success of this venture. Then bring the right group of people together to resolve the issue. For example, one manager might identify “activity mania—we like to be so busy that we don’t set or manage priorities.”

Once each leader has chosen his or her three potential obstacles, share the lists and agree on the three that are most worrisome for this particular undertaking.

Finally, as a leadership team, discuss what can and must be done to reduce and hopefully eliminate the negative impact of the viruses. Tool 8-2 lists many of the most common viruses that impede change. You can use this tool to help you identify your most worrisome obstacles.

TOOL 8-2

Using the organization virus detector: identifying the three most important cultural risk factors in managing change in your organization

The RBL Group uses this cultural virus tool to help teams of managers identify organization risk factors and then share how they manifest and what could be done to eliminate them. The full tool has thirty-six common viruses that impede change. Managers are asked to select one or two viruses that they consider the most threatening to the organization’s ability to work effectively. The complete virus detector can be licensed from the RBL Group.

| Common cultural risk factors, or viruses, in managing change in your organization (sample viruses) |

|---|

| 1. Overinform: We meet and meet again before we decide, which slows down decisions. |

| 2. Have it my way: We don’t learn from each other; “not invented here” syndrome. |

| 3. Good, but . . . : Criticism is a company sport. We always find something wrong. |

| 4. False positive: We agree in person, then disagree in private. |

| 5. We know best: We know what our customers need far better than they do. |

The Road to Abilene

A favorite teaching moment of ours was created years ago by Professor Jerry Harvey.11 Harvey described what he called the Abilene paradox; alternatively, it has come to be known as the paradox of agreement. The fable goes as follows:

On a hot afternoon visiting in Coleman, Texas, the family is comfortably playing dominoes on a porch, until the father-in-law suggests that they take a trip to Abilene [fifty-three miles north] for dinner. The wife says, “Sounds like a great idea.” The husband, despite having reservations because the drive is long and hot, thinks that his preferences must be out-of-step with the group and says, “Sounds good to me. I just hope your mother wants to go.” The mother-in-law then says, “Of course I want to go. I haven’t been to Abilene in a long time.”

The drive is hot, dusty, and long. When they arrive at the cafeteria, the food is as bad as the drive. They arrive back home four hours later, exhausted.

One of them dishonestly says, “It was a great trip, wasn’t it?” The mother-in-law says that, actually, she would rather have stayed home, but went along since the other three were so enthusiastic. The husband says, “I wasn’t delighted to be doing what we were doing. I only went to satisfy the rest of you.” The wife says, “I just went along to keep you happy. I would have had to be crazy to want to go out in the heat like that.” The father-in-law then says that he only suggested it because he thought the others might be bored.

The group sits back, perplexed that they together decided to take a trip which none of them wanted. They each would have preferred to sit comfortably, but did not admit to it when they still had time to enjoy the afternoon.12

The message of the Abilene fable is to manage the journey actively, and this suggests an additional tool of change management we might call second session C. The original session C is an invention of General Electric. Twice annually, the executive team, starting with CEO Jeff Immelt, reviews the organization and talent of each of GE’s businesses. We suggest the addition of a semiannual corporate review of agile-talent activity within the organization. Leaders ought to regularly and systematically ask how well the organization is utilizing its agile talent; discussion should include problematic areas and ways in which the organization is performing brilliantly in how it seeks and works with external help. We expand on this approach in the next chapter.

Summary

As organizations develop an increasing depth and range of agile-talent solutions, change management becomes a more critical skill. As other chapters have pointed out, the culture and human capital practices of the organization will have a significant impact on the reaction to third-party experts and on the effectiveness of their productivity. However, leaders have ways to better manage the change processes and the behavior of the organization to increase the effectiveness of its agile talent. In the next and last chapter of the book, we take a broader lens and consider how agile talent is developing and its implications for the future.