Chapter 4

THE MONEY MARKETS

Part of the global debt capital markets, the money markets are a separate market in their own right. Generally, money market securities are defined as debt instruments with an original maturity of less than 1 year.

Money markets exist in every market economy, which is practically every country in the world. They are often the first element of a developing capital market. Money market debt is an important part of global capital markets, and facilitates the smooth running of the banking industry, as well as providing working capital for industrial and commercial corporate institutions. The market provides users with a wide range of opportunities and funding possibilities, and is characterised by the diverse range of products that can be traded within it. Money market instruments allow issuers, including financial organisations and corporates, to raise funds for short‐term periods at relatively low interest rates. These issuers include sovereign governments, who issue Treasury bills (T‐bills), corporates issuing commercial paper (CP), and banks issuing bills and certificates of deposit (CDs). At the same time, investors are attracted to the market because the instruments are highly liquid and carry relatively low credit risk. The Treasury bill market in any country is that country's lowest risk instrument, and consequently carries the lowest yield of any debt instrument. Indeed, the first market that develops in any country is usually the Treasury bill market. Investors in the money market include banks, local authorities, corporations, money market investment funds and mutual funds, and individuals.

In addition to cash instruments, in certain jurisdictions the money markets also consist of a range of exchange‐traded and over‐the‐counter derivative instruments. These instruments are used mainly to establish future borrowing and lending rates, and to hedge or change existing interest‐rate exposure. This activity is carried out by banks, central banks, and corporates. The main derivatives are short‐term interest‐rate futures, forward rate agreements, and short‐dated interest‐rate swaps, such as overnight index swaps.

In this chapter we review the cash and derivative instruments traded in the money market, including interest‐rate futures and forward rate agreements.

INTRODUCTION

The cash instruments traded in money markets include the following:

- Time deposits;

- Treasury bills;

- Certificates of deposit;

- Commercial paper;

- Banker's acceptances;

- Bills of exchange;

- Repo and stock lending.

Treasury bills are used by sovereign governments to raise short‐term funds, while certificates of deposit (CDs) are used by banks to raise finance. The other instruments are used by corporates and occasionally banks. Each instrument represents an obligation on the borrower to repay the amount borrowed on the maturity date, together with interest if this applies. The instruments above fall into one of two main classes of money market securities: those quoted on a yield basis and those quoted on a discount basis. These two terms are discussed below. A repurchase agreement or “repo” is also a money market instrument.

The calculation of interest in the money markets often differs from the calculation of accrued interest in the corresponding bond market. Generally, the day‐count convention in the money market is the exact number of days that the instrument is held over the number of days in the year. In the UK sterling market, the year base is 365 days, so the interest calculation for sterling money market instruments is given by (4.1):

However, the majority of currencies, including the US dollar and the euro, calculate interest on a 360‐day base. The process by which an interest rate quoted on one basis is converted to one quoted on the other basis is shown at (4.18). Those markets that calculate interest based on a 365‐day year are also listed in the last section of this chapter.

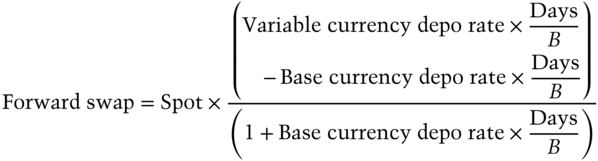

Dealers will want to know the interest day base for a currency before dealing in it as foreign exchange (FX) or as money markets. Bloomberg users can use screen DCX to look up the number of days of an interest period. For instance, Figure 4.1 shows screen DCX for the US dollar market, for a loan taken out on 16 November 2005 for spot value on 18 November 2005 for a straight 3‐month period. This matures on 21 February 2006; we see from Figure 4.1 that this is a good day. We see also that 20 February 2006 is a USD holiday. The loan period is actually 95 days, and 93 days under the 30/360‐day convention (a bond market accrued interest convention). The number of business days is 62.

Figure 4.1 Bloomberg screen DCX used for a US dollar market, 3‐month loan taken out for value 18 November 2005

© 2005 Bloomberg Finance LP. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

For the same loan taken out in Singapore dollars, look at Figure 4.2. This shows that 20 February 2006 is not a public holiday for SGD and so the loan runs for the period 18 December 2005 to 20 February 2006.

Figure 4.2 Bloomberg screen DCX for a Singapore dollar market, 3‐month loan taken out for value 18 November 2005

© 2005 Bloomberg Finance LP. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Settlement of money market instruments can be for value today (generally only when traded before midday), tomorrow, or 2 days forward, which is known as spot. The latter is most common.

SECURITIES QUOTED ON A YIELD BASIS

Two of the instruments in the list in the Introduction are yield‐based instruments.

Money market deposits

These are fixed interest term deposits of up to 1 year with banks and securities houses. They are also known as time deposits or clean deposits. They are not negotiable so cannot be liquidated before maturity. The interest rate on the deposit is fixed for the term and related to the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) of the same term. Interest and capital are paid on maturity.

The effective rate on a money market deposit is the annual equivalent interest rate for an instrument with a maturity of less than 1 year.

Certificates of deposit

Certificates of deposit (CDs) are receipts from banks for deposits that have been placed with them. They were first introduced in the sterling market in 1958. The deposits themselves carry a fixed rate of interest related to LIBOR and have a fixed term to maturity, so cannot be withdrawn before maturity. However, the certificates themselves can be traded in a secondary market – that is, they are negotiable. CDs are therefore very similar to negotiable money market deposits, although the yields are usually below the equivalent tenor deposit rates because of the added benefit of liquidity. Most CDs issued are of between 1 and 3 months' maturity, although they do trade in maturities of 1 to 5 years. Interest is paid on maturity except for CDs lasting longer than 1 year, where interest is paid annually or, occasionally, semi‐annually.

Banks, merchant banks, and building societies issue CDs to raise funds to finance their business activities. A CD will have a stated interest rate and fixed maturity date, and can be issued in any denomination. On issue a CD is sold for face value, so the settlement proceeds of a CD on issue are always equal to its nominal value. The interest is paid, together with the face amount, on maturity. The interest rate is sometimes called the coupon, but unless the CD is held to maturity this will not equal the yield, which is of course the current rate available in the market and varies over time. The largest group of CD investors are banks, money market funds, corporates, and local authority treasurers.

Unlike coupons on bonds, which are paid in rounded amounts, CD coupons are calculated to the exact day.

CD yields

The coupon quoted on a CD is a function of the credit quality of the issuing bank, its expected liquidity level in the market and, of course, the maturity of the CD, as this will be considered relative to the money market yield curve. As CDs are issued by banks as part of their short‐term funding and liquidity requirement, issue volumes are driven by the demand for bank loans and the availability of alternative sources of funds for bank customers. The credit quality of the issuing bank is the primary consideration, however. In the sterling market, the lowest yield is paid by “clearer” CDs, which are CDs issued by the clearing banks – such as Lloyds Bank, HSBC, and Barclays plc. In the US market, “prime” CDs, issued by highly rated domestic banks, trade at a lower yield than non‐prime CDs. In both markets, CDs issued by foreign banks – such as French or Japanese banks – will trade at higher yields.

Euro‐CDs, which are CDs issued in a different currency from that of the home currency, also trade at higher yields in the US because of reserve and deposit insurance restrictions.

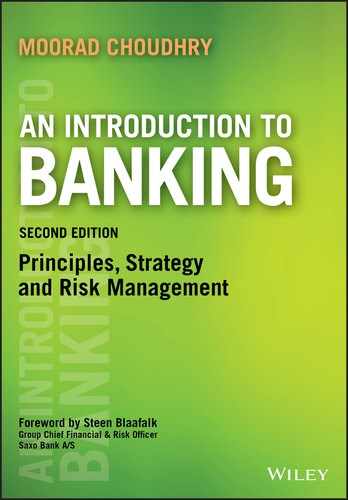

If the current market price of the CD including accrued interest is P and the current quoted yield is r, the yield can be calculated given the price using (4.2):

The price can be calculated given the yield using (4.3):

where

| C | = | Quoted coupon on the CD; |

| M | = | Face value of the CD; |

| B | = | Year day basis (365 or 360); |

| F | = | Maturity value of the CD; |

| Nim | = | Number of days between issue and maturity; |

| Nsm | = | Number of days between settlement and maturity; |

| Nis | = | Number of days between issue and settlement. |

After issue a CD can be traded in the secondary market. The secondary market in CDs in the UK is very liquid, and CDs will trade at the rate prevalent at the time, which will invariably be different from the coupon rate on the CD at issue. When a CD is traded in the secondary market, the settlement proceeds will need to take into account interest that has accrued on the paper and the different rate at which the CD has now been dealt. The formula for calculating the settlement figure is given at (4.4), which applies to the sterling market and its 365 day‐count basis:

The settlement figure for a new issue CD is, of course, its face value…!1

The tenor of a CD is the life of the CD in days, while days remaining is the number of days left to maturity from the time of trade.

The return on holding a CD is given by (4.5):

SECURITIES QUOTED ON A DISCOUNT BASIS

The remaining money market instruments are all quoted on a discount basis, and so are known as “discount” instruments. This means that they are issued on a discount to face value, and are redeemed on maturity at face value. Hence, T‐bills, bills of exchange, banker's acceptances, and CP are examples of money market securities that are quoted on a discount basis – that is, they are sold on the basis of a discount to par. The difference between the price paid at the time of purchase and the redemption value (par) is the interest earned by the holder of the paper. Explicit interest is not paid on discount instruments, rather interest is reflected implicitly in the difference between the discounted issue price and the par value received at maturity.

Treasury bills

Treasury bills (T‐bills) are short‐term government “IOUs” of short duration, often 3‐month maturity. For example, if a bill is issued on 10 January it will mature on 10 April. Bills of 1‐month and 6‐month maturity are issued in certain markets, but only rarely by the UK Treasury. On maturity the holder of a T‐bill receives the par value of the bill by presenting it to the central bank. In the UK, most such bills are denominated in sterling but issues are also made in euros. In a capital market, T‐bill yields are regarded as the risk‐free yield, as they represent the yield from short‐term government debt. In emerging markets, they are often the most liquid instruments available for investors.

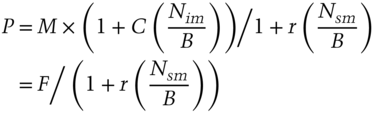

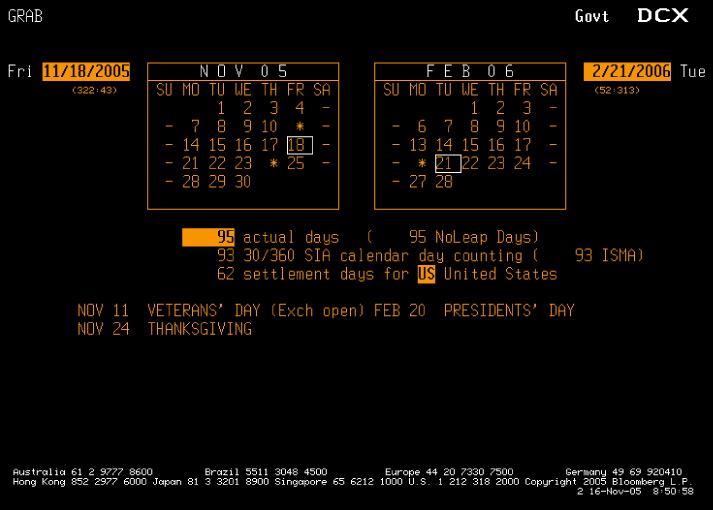

A sterling T‐bill with £10 million face value issued for 91 days will be redeemed on maturity at £10 million. If the 3‐month yield at the time of issue is 5.25%, the price of the bill at issue is:

In the UK market, the interest rate on discount instruments is quoted as a discount rate rather than a yield. This is the amount of discount expressed as an annualised percentage of the face value, and not as a percentage of the original amount paid. By definition, the discount rate is always lower than the corresponding yield. If the discount rate on a bill is d, then the amount of discount is given by (4.6):

The price P paid for the bill is the face value minus the discount amount, given by (4.7):

If we know the yield on the bill, then we can calculate its price at issue by using the simple present value formula, as shown at (4.8):

The discount rate d for T‐bills is calculated using (4.9):

The relationship between discount rate and true yield is given by (4.10):

Banker's acceptances

A banker's acceptance is a written promise issued by a borrower to a bank to repay borrowed funds. The lending bank lends funds and in return accepts the banker's acceptance. The acceptance is negotiable and can be sold in the secondary market. The investor who buys the acceptance can collect the loan on the day that repayment is due. If the borrower defaults, the investor has legal recourse to the bank that made the first acceptance. Banker's acceptances are also known as bills of exchange, bank bills, trade bills, or commercial bills.

Essentially, banker's acceptances are instruments created to facilitate commercial trade transactions. The instrument is called a banker's acceptance because a bank accepts the ultimate responsibility to repay the loan to its holder. The use of banker's acceptances to finance commercial transactions is known as acceptance financing. The transactions for which acceptances are created include import and export of goods, the storage and shipping of goods between two overseas countries, where neither the importer nor the exporter is based in the home country,2 and the storage and shipping of goods between two entities based at home. Acceptances are discount instruments and are purchased by banks, local authorities, and money market investment funds.

The rate that a bank charges a customer for issuing a banker's acceptance is a function of the rate at which the bank thinks it will be able to sell it in the secondary market. A commission is added to this rate. For ineligible banker's acceptances (see below), the issuing bank will add an amount to offset the cost of additional reserve requirements.

Eligible banker's acceptance

An accepting bank that chooses to retain a banker's acceptance in its portfolio may be able to use it as collateral for a loan obtained from the central bank during open market operations – for example, the Bank of England in the UK and the Federal Reserve in the US. Not all acceptances are eligible to be used as collateral in this way, as they must meet certain criteria set by the central bank. The main requirement for eligibility is that the acceptance must be within a certain maturity band (a maximum of 6 months in the US and 3 months in the UK), and that it must have been created to finance a self‐liquidating commercial transaction. In the US, eligibility is also important because the Federal Reserve imposes a reserve requirement on funds raised via banker's acceptances that are ineligible. Banker's acceptances sold by an accepting bank are potential liabilities for the bank, but the reserve imposes a limit on the amount of eligible banker's acceptances that a bank may issue. Bills eligible for deposit at a central bank enjoy a finer rate than ineligible bills, and also act as a benchmark for prices in the secondary market.

COMMERCIAL PAPER

Commercial paper (CP) is a short‐term money market funding instrument issued by corporates. In the UK and US it is a discount instrument. A company's short‐term capital and working capital requirement is usually sourced directly from banks in the form of bank loans. An alternative short‐term funding instrument is CP, which is available to corporates that have a sufficiently strong credit rating. CP is a short‐term unsecured promissory note. The issuer of the note promises to pay its holder a specified amount on a specified maturity date. CP normally has a zero coupon and trades at a discount to its face value. The discount represents interest to the investor in the period to maturity. CP is typically issued in bearer form, although some issues are in registered form.

Originally, the CP market was restricted to borrowers with high credit ratings, and although lower rated borrowers do now issue CP, sometimes by obtaining credit enhancements or setting up collateral arrangements, issuance in the market is still dominated by highly rated companies. The majority of issues are very short term, from 30 to 90 days in maturity; it is extremely rare to observe paper with a maturity of more than 270 days or 9 months. This is because of regulatory requirements in the US,3 which state that debt instruments with a maturity of less than 270 days need not be registered. Companies therefore issue CP with a maturity lower than 9 months and so avoid the administration costs associated with registering issues with the SEC.

There are two major markets, the US dollar market with an outstanding amount in 2005 of just under $1 trillion, and the eurocommercial paper market with an outstanding value of $490 billion at the end of 2005.4Commercial paper markets are wholesale markets, and transactions are typically very large. In the US, over a third of all CP is purchased by money market unit trusts, known as mutual funds; other investors include pension fund managers, retail or commercial banks, local authorities, and corporate treasurers. A comparison between US CP and eurocommercial paper is given in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Comparison of US CP and eurocommercial paper

| US CP | Eurocommercial paper | |

| Currency | US dollar | Any euro currency |

| Maturity | 1–270 days | 2–365 days |

| Common maturity | 30–180 days | 30–90 days |

| Interest | Zero coupon, issued at discount | Fixed coupon |

| Quotation | On a discount rate basis | On a yield basis |

| Settlement | T+0; T+1 | T+2 |

| Registration | Bearer form | Bearer form |

| Negotiable | Yes | Yes |

Although there is a secondary market in CP, very little trading activity takes place since investors generally hold CP until maturity. This is to be expected because investors purchase CP that matches their specific maturity requirement. When an investor does wish to sell paper, it can be sold back to the dealer or, where the issuer has placed the paper directly in the market (and not via an investment bank), it can be sold back to the issuer.

Commercial paper programmes

The issuers of CP are often divided into two categories of company: banking and financial institutions, and non‐financial companies. The majority of CP issues are by financial companies. Financial companies include not only banks but also the financing arms of corporates – such as British Airways, BP, and Ford Motor Credit. Most of the issuers have strong credit ratings, but lower rated borrowers have tapped the market, often after arranging credit support from a higher rated company, such as a letter of credit from a bank, or by arranging collateral for the issue in the form of high‐quality assets such as Treasury bonds. CP issued with credit support is known as credit‐supported commercial paper, while paper backed by assets is known naturally enough as asset‐backed commercial paper. Paper that is backed by a bank letter of credit is termed LOC paper. Although banks charge a fee for issuing letters of credit, borrowers are often happy to arrange for this, since by doing so they are able to tap the CP market. The yield paid on an issue of CP will be lower than that on a commercial bank loan.

Although CP is a short‐dated security, typically of 3–6‐month maturity, it is issued within a longer term programme, usually for 3–5 years for euro paper; US CP programmes are often open ended. For example, a company might arrange a 5‐year CP programme with a limit of $100 million. Once the programme is established, the company can issue CP up to this amount – say, for maturities of 30 or 60 days. The programme is continuous and new CP can be issued at any time, daily if required. The total amount in issue cannot exceed the limit set for the programme. A CP programme can be used by a company to manage its short‐term liquidity – that is, its working capital requirements. New paper can be issued whenever a need for cash arises, and for an appropriate maturity.

Issuers often roll over their funding and use funds from a new issue of CP to redeem a maturing issue. There is a risk that an issuer might be unable to roll over the paper where there is a lack of investor interest in the new issue. To provide protection against this risk, issuers often arrange a standby line of credit from a bank, normally for all of the CP programme, to draw against in the event that it cannot place a new issue.

There are two methods by which CP is issued, known as direct‐issued or direct paper and dealer‐issued or dealer paper. Direct paper is sold by the issuing firm directly to investors, and no agent bank or securities house is involved. It is common for financial companies to issue CP directly to their customers, often because they have continuous programmes and constantly roll over their paper. It is therefore cost‐effective for them to have their own sales arm and sell their CP direct. The treasury arms of certain non‐financial companies also issue direct paper. This includes, for example, British Airways plc corporate treasury, which runs a continuous direct CP programme, used to provide short‐term working capital for the company. Dealer paper is paper that is sold using a banking or securities house intermediary. In the US, dealer CP is effectively dominated by investment banks, as retail (commercial) banks were until recently forbidden from underwriting commercial paper. This restriction has since been removed and now both investment banks and commercial paper underwrite dealer paper.

Commercial paper yields

CP is sold at a discount to its maturity value, and the difference between this maturity value and the purchase price is the interest earned by the investor. The CP day‐count base is 360 days in the US and euro markets, and 365 days in the UK. The paper is quoted on a discount yield basis, in the same manner as T‐bills. The yield on CP follows that of other money market instruments and is a function of the short‐dated yield curve. The yield on CP is higher than the T‐bill rate; this is due to the credit risk that the investor is exposed to when holding CP, for tax reasons (in certain jurisdictions interest earned on T‐bills is exempt from income tax) and because of the lower level of liquidity available in the CP market. CP also pays a higher yield than CDs due to the lower liquidity of the CP market.

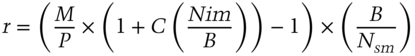

Although CP is a discount instrument and trades as such in the US and UK, euro currency eurocommercial paper trades on a yield basis, similar to a CD. The expressions below illustrate the relationship between true yield and discount rate:

where M is the face value of the instrument, rd is the discount rate, and r the true yield.

REPO

The term repo is used to cover one of two different transactions, the classic repo and the sell/buyback, and sometimes is spoken of in the same context as a similar instrument, the stock loan. A fourth instrument is also economically similar in some respects to a repo, known as the total return swap, which is now commonly encountered as part of the market in credit derivatives. However, although these transactions differ in terms of their mechanics, legal documentation, and accounting treatment, the economic effect of each of them is very similar. The structure of any particular market and the motivations of particular counterparties will determine which transaction is entered into; there is also some crossover between markets and participants.

Market participants enter into classic repo because they wish to invest cash, for which the transaction is deemed to be cash driven, or because they wish to borrow a certain stock, for which purpose the trade is stock driven. A sell/buyback, which is sometimes referred to as a buy–sell, is entered into for similar reasons, but the trade itself operates under different mechanics and documentation.5 A stock loan is just that, a borrowing of stock against a fee. Long‐term holders of stock will therefore enter into stock loans simply to enhance their return.

During the interbank liquidity crisis from September 2008 to well into 2009, when unsecured inter‐bank markets dried up, repo was the only funding mechanism still available to many banks.

Definition

A repo agreement is a transaction in which one party sells securities to another, and at the same time and as part of the same transaction, commits to repurchase identical securities on a specified date at a specified price. The seller delivers securities and receives cash from the buyer. The cash is supplied at a predetermined rate – the repo rate – which remains constant during the term of the trade. On maturity, the original seller receives back collateral of equivalent type and quality and returns the cash plus repo interest. One party to the repo requires either the cash or the securities and provides collateral to the other party, as well as some form of compensation for the temporary use of the desired asset. Although legal title to the securities is transferred, the seller retains both the economic benefits and the market risk of owning them. This means that the “seller” will suffer if the market value of the collateral drops during the term of the repo, as she still retains beneficial ownership of the collateral. The “buyer” in a repo is not affected in P&L account terms if the value of the collateral drops, although there are other concerns for the buyer if this happens.

We have given here the legal definition of repo. However, the purpose of the transaction as we have described above is to borrow or lend cash, which is why we have used inverted commas when referring to sellers and buyers. The “seller” of stock is really interested in borrowing cash, on which she or he will pay interest at a specified interest rate. The “buyer” requires security or collateral against the loan he or she has advanced, and/or the specific security to borrow for a period of time. The first and most important thing to state is that repo is a secured loan of cash, and would be categorised as a money market yield instrument.6

THE CLASSIC REPO

The classic repo is the instrument encountered in the US, UK, and other markets. In a classic repo, one party will enter into a contract to sell securities, simultaneously agreeing to purchase them back at a specified future date and price. The securities can be bonds or equities but can also be money market instruments, such as T‐bills. The buyer of the securities is handing over cash, which on the termination of the trade will be returned to him, and on which he will receive interest.

The seller in a classic repo is selling or offering stock, and therefore receiving cash, whereas the buyer is buying or bidding for stock, and consequently paying cash. So, if the 1‐week repo interest rate is quoted by a market‐making bank as “512–514”, this means that the market‐maker will bid for stock – that is, lend the cash – at 5.50% and offers stock or pays interest on cash at 5.25%.

Illustration of classic repo

There will be two parties to a repo trade, let us say Bank A (the seller of securities) and Bank B (the buyer of securities). On the trade date the two banks enter into an agreement whereby on a set date – the value or settlement date – Bank A will sell to Bank B a nominal amount of securities in exchange for cash.7 The price received for the securities is the market value of the stock on the value date. The agreement also demands that on the termination date Bank B will sell identical stock back to Bank A at the previously agreed price, and, consequently, Bank B will have its cash returned with interest at the agreed repo rate.

In essence, a repo agreement is a secured loan (or collateralised loan) in which the repo rate reflects the interest charged.

On the value date, stock and cash change hands. This is known as the start date, first leg, or opening leg, while the termination date is known as the second leg or closing leg. When the cash is returned to Bank B, it is accompanied by the interest charged on the cash during the term of the trade. This interest is calculated at a specified rate known as the repo rate. It is important to remember that, although in legal terms the stock is initially “sold” to Bank B, the economic effects of ownership are retained with Bank A. This means that if the stock falls in price it is Bank A that will suffer a capital loss. Similarly, if the stock involved is a bond and there is a coupon payment during the term of trade, this coupon is to the benefit of Bank A and, although Bank B will have received it on the coupon date, it must be handed over on the same day or immediately after to Bank A. This reflects the fact that, although legal title to the collateral passes to the repo buyer, the economic costs and benefits of the collateral remain with the seller.

A classic repo transaction is subject to a legal contract signed in advance by both parties. A standard document will suffice; it is not necessary to sign a legal agreement prior to each transaction.

Note that, although we have called the two parties in this case “Bank A” and “Bank B”, it is not only banks that are involved in repo transactions – we have used these terms for the purposes of illustration only.

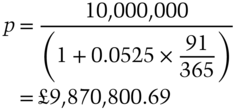

The basic mechanism is illustrated in Figure 4.8.

Figure 4.8 Classic repo transaction

A seller in a repo transaction is entering into a repo, whereas a buyer is entering into a reverse repo. In Figure 4.8 the repo counterparty is Bank A, while Bank B is entering into a reverse repo. That is, a reverse repo is a purchase of securities that are sold back on termination. As is evident from Figure 4.8, every repo is a reverse repo, and the name given is dependent on whose viewpoint one is looking at the transaction from.8

Examples of classic repo

The basic principle is illustrated with the following example. This considers a specific repo – that is, one in which the collateral supplied is specified as a particular stock – as opposed to a general collateral (GC) trade in which a basket of collateral can be supplied, of any particular issue, as long as it is of the required type and credit quality.

We first consider a classic repo in the UK gilt market between two market counterparties in the 5.75% Treasury 2012 gilt stock as at 2 December 2005. The terms of the trade are given in Table 4.2 and the trade is illustrated in Figure 4.9.

Table 4.2 Terms of a classic repo trade

| Trade date | 2 December 2005 |

| Value date | 5 December 2005 |

| Repo term | 1 month |

| Termination date | 5 January 2006 |

| Collateral (stock) | UKT 5% 2012 |

| Nominal amount | £10,000,000 |

| Price | 104.17 |

| Accrued interest (89 days) | 1.2292818 |

| Dirty price | 105.3993 |

| Haircut | 0% |

| Settlement proceeds (wired amount) | £10,539,928.18 |

| Repo rate | 4.50% |

| Repo interest | £40,282.74 |

| Termination proceeds | £10,580,210.92 |

Figure 4.9 Classic repo trade example

The repo counterparty delivers to the reverse repo counterparty £10 million nominal of the stock, and in return receives the purchase proceeds. In this example, no margin has been taken, so the start proceeds are equal to the market value of the stock, which is £10,539,928. It is common for a rounded sum to be transferred on the opening leg. The repo rate is 4.50%, so the repo interest charged for the trade is:

or £40,282.74. The sterling market day‐count basis is actual/365, so the repo interest is based on a 7‐day repo rate of 4.50%. Repo rates are agreed at the time of the trade and are quoted, like all interest rates, on an annualised basis. The settlement price (dirty price) is used because it is the market value of the bonds on the particular trade date and therefore indicates the cash value of the gilts. By doing this, the cash investor minimises credit exposure by equating the value of the cash and the collateral.

On termination, the repo counterparty receives back its stock, for which it hands over the original proceeds plus the repo interest calculated above.

REPO COLLATERAL

The collateral in a repo trade is the security passed to the lender of cash by the borrower of cash. It is not always secondary to the transaction; in stock‐driven transactions the requirement for specific collateral is the motivation behind the trade. However, in a classic repo or sell/buyback, the collateral is always the security handed over against cash.9 In a stock loan transaction, the collateral against stock lent can be either securities or cash. Collateral is used in repo to provide security against default by the cash borrower. Therefore, it is protection against counterparty risk or credit risk, the risk that the cash‐borrowing counterparty defaults on the loan. A secured or collateralised loan is theoretically lower credit risk exposure for a cash lender compared with an unsecured loan.

The most commonly encountered collateral is government bonds, and the repo market in government bonds is the largest in the world. Other forms of collateral include Eurobonds, other forms of corporate and supranational debt, asset‐backed bonds, mortgage‐backed bonds, money market securities such as T‐bills, and equities.

In any market where there is a defined class of collateral of identical credit quality, this is known as general collateral (GC). So, for example, in the UK gilt market a GC repo is one where any gilt will be acceptable as repo collateral. Another form of GC might be “AA‐rated sterling Eurobonds”. In the US market, the term stock collateral is sometimes used to refer to GC securities. In equity repo it is more problematic to define GC and by definition almost all trades are specifics; however, it is becoming more common for counterparties to specify any equity being acceptable if it is in an established index – for example, a FTSE 100 or a CAC 40 stock – and this is perhaps the equity market equivalent of GC. If a specific security is required in a reverse repo or as the other side of a sell/buyback, this is known as a specific or specific collateral. A specific stock that is in high demand in the market, such that the repo rate against it is significantly different from the GC rate, is known as a special.

Where a coupon payment is received on collateral during the term of a repo, it is to the benefit of the repo seller. Under the standard repo legal agreement, legal title to collateral is transferred to the buyer during the term of the repo, but it is accepted that the economic benefits remain with the seller. For this reason, the coupon is returned to the seller. In classic repo (and in stock lending) the coupon is returned to the seller on the dividend date, or in some cases on the following date. In a sell/buyback the effect of the coupon is incorporated in the repurchase price. This includes interest on the coupon amount that is payable by the buyer during the period from the coupon date to the buyback date.

LEGAL TREATMENT

Classic repo is carried out under a legal agreement that defines the transaction as a full transfer of the title to the stock. The standard legal agreement is the PSA/ISMA GRMA, which we review in the book An Introduction to Repo Markets 3e. It is now possible to trade sell/buybacks under this agreement as well. This agreement was based on the PSA standard legal agreement used in the US domestic market, and was compiled because certain financial institutions were not allowed to borrow or lend securities legally. By transacting repo under the PSA agreement, these institutions were defined as legally buying and selling securities rather than borrowing or lending them.

MARGIN

To reduce the level of risk exposure in a repo transaction, it is common for the lender of cash to ask for a margin, which is where the market value of collateral is higher than the value of cash lent out in the repo. This is a form of protection should the cash‐borrowing counterparty default on the loan. Another term for margin is overcollateralisation or a haircut. There are two types of margin: initial margin taken at the start of the trade and variation margin, which is called if required during the term of the trade.

Initial margin

The cash proceeds in a repo are typically no more than the market value of the collateral. This minimises credit exposure by equating the value of the cash to that of the collateral. The market value of the collateral is calculated at its dirty price, not clean price – that is, including accrued interest. This is referred to as accrual pricing. To calculate the accrued interest on the (bond) collateral we require the day‐count basis for the particular bond.

The start proceeds of a repo can be less than the market value of the collateral by an agreed amount or percentage. This is known as the initial margin or haircut. The initial margin protects the buyer against:

- A sudden fall in the market value of the collateral;

- Illiquidity of collateral;

- Other sources of volatility of value (for example, approaching maturity);

- Counterparty risk.

The margin level of repo varies from 0–2% for collateral such as UK gilts, to 5% for cross‐currency and equity repo, to 10–35% for emerging market debt repo.

In both classic repo and sell/buyback, any initial margin is given to the supplier of cash in the transaction. This remains the case in the case of specific repo. For initial margin, the market value of the bond collateral is reduced (or given a haircut) by the percentage of the initial margin and the nominal value determined from this reduced amount. In a stock loan transaction, the lender of stock will ask for margin.

There are two methods for calculating margin; for a 2% margin this could be one of the following:

- The dirty price of the bonds × 0.98;

- The dirty price of the bonds

1.02.

1.02.

The two methods do not give the same value! The RRRA repo page on Bloomberg uses the second method for its calculations, and this method is turning into something of a convention.

For a 2% margin level, the PSA/ISMA GRMA defines a “margin ratio” as:

The size of margin required in any particular transaction is a function of the following:

- The credit quality of the counterparty supplying the collateral: for example, a central bank counterparty, inter‐bank counterparty, and corporate will all suggest different margin levels;

- The term of the repo: an overnight repo is inherently lower risk than a 1‐year repo;

- The duration (price volatility) of the collateral: for example, a T‐bill against the long bond;

- The existence or absence of a legal agreement: a repo traded under a standard agreement is considered lower risk.

However, in the final analysis, margin is required to guard against market risk, the risk that the value of collateral will drop during the course of the repo. Therefore, the margin call must reflect the risks prevalent in the market at the time; extremely volatile market conditions may call for large increases in initial margin.

Variation margin

The market value of collateral is maintained through the use of variation margin. So, if the market value of collateral falls, the buyer calls for extra cash or collateral. If the market value of collateral rises, the seller calls for extra cash or collateral. In order to reduce the administrative burden, margin calls can be limited to changes in the market value of collateral in excess of an agreed amount or percentage, which is called a margin maintenance limit.

The standard market documentation that exists for the three structures covered so far includes clauses that allow parties to a transaction to call for variation margin during the term of a repo. This can be in the form of extra collateral, if the value of collateral has dropped in relation to the asset exchanged, or a return of collateral, if the value has risen. If the cash‐borrowing counterparty is unable to supply more collateral where required, he will have to return a portion of the cash loan. Both parties have an interest in making and meeting margin calls, although there is no obligation. The level at which variation margin is triggered is often agreed beforehand in the legal agreement put in place between individual counterparties. Although primarily viewed as an instrument used by the supplier of cash against a fall in the value of the collateral, variation margin can of course also be called by the repo seller if the value of the collateral has risen.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE

The market in foreign exchange is an excellent example of a liquid, transparent, and immediate global financial market. Rates in the foreign exchange (FX) markets move at a rapid pace and in fact trading in FX is a different discipline to bond trading or money markets trading. There is considerable literature on the FX markets, as it is a separate subject in its own right. However, some banks organise their forward desk as part of the money market desk and not the foreign exchange desk, necessitating its inclusion in this chapter. For this reason, we present an overview summary of FX in this chapter, both spot and forward.

Market conventions

The price quotation for currencies generally follows the ISO convention, which is also used by the SWIFT and Reuters dealing systems, and is the three‐letter code used to identify a currency, such as USD for US dollar and GBP for sterling. The rate convention is to quote everything in terms of one unit of the US dollar, so that the dollar and Swiss franc rate is quoted as USD/CHF, and is the number of Swiss francs to one US dollar. The exception is for sterling, which is quoted as GBP/USD and is the number of US dollars to the pound. The rate for euros has been quoted both ways round, for example, EUR/USD, although some banks, for example, RBS Financial Markets in the UK, quotes euros to the pound, that is GBP/EUR.

Spot exchange rates

A spot FX trade is an outright purchase or sale of one currency against another currency, with delivery 2 working days after the trade date. Non‐working days do not count, so a trade on a Friday is settled on the following Tuesday. There are some exceptions to this, for example, trades of US dollar against Canadian dollar are settled the next working day. Note that in some currencies, generally in the Middle East, markets are closed on Friday but open on Saturday. A settlement date that falls on a public holiday in the country of one of the two currencies is delayed for settlement by that day. An FX transaction is possible between any two currencies. However, to reduce the number of quotes that need to be made the market generally quotes only against the US dollar or occasionally sterling or euro, so that the exchange rate between two non‐dollar currencies is calculated from the rate for each currency against the dollar. The resulting exchange rate is known as the cross‐rate. Cross‐rates themselves are also traded between banks in addition to dollar‐based rates. This is usually because the relationship between two rates is closer than that of either against the dollar, for example, the Swiss franc moves more closely in line with the euro than against the dollar, so in practice one observes that the dollar/Swiss franc rate is more a function of the euro/franc rate.

The spot FX quote is a two‐way bid–offer price, just as in the bond and money markets, and indicates the rate at which a bank is prepared to buy the base currency against the variable currency; this is the “bid” for the variable currency, so is the lower rate. The other side of the quote is the rate at which the bank is prepared to sell the base currency against the variable currency. For example, a quote of 1.6245–1.6255 for GBP/USD means that the bank is prepared to buy sterling for $1.6245 and to sell sterling for $1.6255. The convention in the FX market is uniform across countries, unlike the money markets. Although the money market convention for bid–offer quotes is, for example, 5½–5¼%, meaning that the “bid” for paper – the rate at which the bank will lend funds, say in the CD market – is the higher rate and always on the left, this convention is reversed in certain countries. In the FX markets, the convention is always the same as the one just described.

The difference between the two sides in a quote is the bank's dealing spread. Rates are quoted to 1/100th of a cent, known as a pip. In the quote above, the spread is 10 pips; however, this amount is a function of the size of the quote number, so that the rate for USD/JPY at, say, 110.10–110.20 indicates a spread of 0.10 yen. Generally, only the pips in the two rates are quoted, so that, for example, the quote above would be simply “45–55”. The “big figure” is not quoted.

Forward exchange rates

We consider forward exchange rates in the next two sections.

Forward outright

The spot exchange rate is the rate for immediate delivery (notwithstanding that actual delivery is 2 days forward). A forward contract or simply forward is an outright purchase or sale of one currency in exchange for another currency for settlement on a specified date at some point in the future. The exchange rate is quoted in the same way as the spot rate, with the bank buying the base currency on the bid side and selling it on the offered side. In some emerging markets no liquid forward market exists, so forwards are settled in cash against the spot rate on the maturity date. These non‐deliverable forwards are considered at the end of this section.

Although some commentators have stated that the forward rate may be seen as the market's view of where the spot rate will be on the maturity date of the forward transaction, this is incorrect. A forward rate is calculated on the current interest rates of the two currencies involved, and the principle of no‐arbitrage pricing ensures that there is no profit to be gained from simultaneous (and opposite) dealing in spot and forward. Consider the following strategy:

- Borrow US dollars for 6 months starting from the spot value date;

- Sell dollars and buy sterling for value spot;

- Deposit the long sterling position for 6 months from the spot value date;

- Sell forward today the sterling principal and interest, which mature in 6 months' time into dollars.

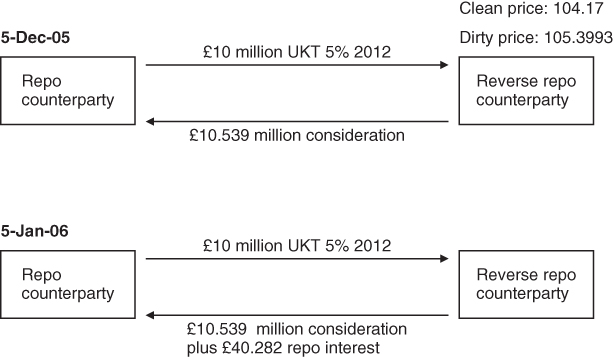

The market will adjust the forward price so that the two initial transactions if carried out simultaneously will generate a zero profit/loss. The forward rates quoted in the trade will be calculated on the 6 months deposit rates for dollars and sterling; in general, the calculation of a forward rate is given as 2.1.

The year day‐count base B will be either 365 or 360 depending on the convention for the currency in question.

Forward swaps

The calculation given above illustrates how a forward rate is calculated and quoted in theory. In practice, as spot rates change rapidly, often many times even in 1 minute, it would be tedious to keep recalculating the forward rate so often. Therefore, banks quote a forward spread over the spot rate, which can then be added or subtracted to the spot rate as it changes. This spread is known as the swap points. An approximate value for the number of swap points is given by (4.16) below.

The approximation is not accurate enough for forwards maturing more than 30 days from now, in which case another equation must be used. This is given as (4.17). It is also possible to calculate an approximate deposit rate differential from the swap points by rearranging (4.16).

Forward cross‐rates

A forward cross‐rate is calculated in the same way as spot cross‐rates. The formulas given for spot cross‐rates can be adapted to forward rates.

Forward‐forwards

A forward‐forward swap is a deal between two forward dates rather than from the spot date to a forward date. This is the same terminology and meaning as in the bond markets, where a forward or a forward‐forward rate is the zero‐coupon interest rate between two points both beginning in the future. In the foreign exchange market, an example would be a contract to sell sterling 3 months forward and buy it back in 6 months' time. Here, the swap is for the 3‐month period between the 3‐month date and the 6‐month date. The reason a bank or corporate might do this is to hedge a forward exposure or because of a particular view it has on forward rates, in effect deposit rates.

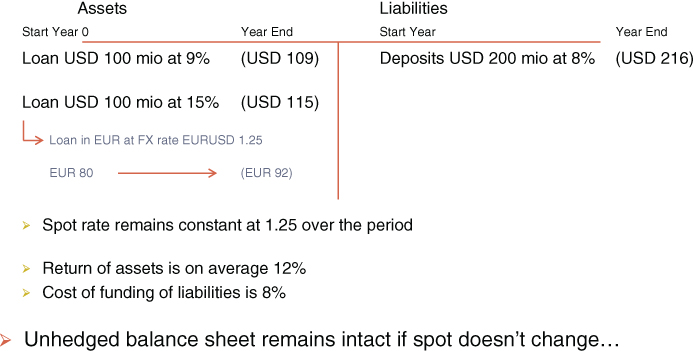

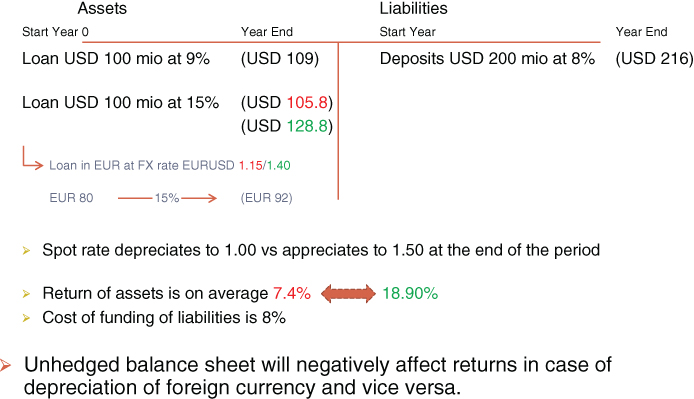

FX BALANCE SHEET HEDGING

The majority of the world's banks hold assets that are denominated in the domestic reporting currency. That said, many vanilla commercial banks originate assets and/or raise liabilities that are in a different currency to their reporting currency. This generates an element of structural balance sheet risk because the reporting currency is different and the FX rate impacts final reporting numbers. Where the asset is funded by liabilities in a different currency, this generates a further liquidity risk exposure.

The approach to hedging this first‐order FX risk (“reporting risk”, if you like) is orthodox as practised by most banks. We present the basic principles as a series illustration of a worked example, shown in Figures 4.10 to 4.13.

Figure 4.10 FX balance sheet hedging- part (ii)

Figure 4.11 FX balance sheet hedging- part (iii)

Figure 4.12 FX balance sheet hedging- part (iv)

Figure 4.13 FX balance sheet hedging‐ part (i)

Other instruments that may be used in off‐balance‐sheet hedging include:

- Cross currency swaps;

- Options.

Exotic options such as knock‐ins, knock‐outs, digitals, or even window barriers will inject optionality into your hedge again but at a price.

It is safe to say that 95% of the world's banks' FX hedging requirements can be met with cash or plain vanilla derivative products. Hedging is as much art as science, so there is often little upside payoff in structuring a sophisticated hedge that costs you almost as much as it is meant to save you.

CURRENCIES USING MONEY MARKET YEAR BASE OF 365 DAYS

- Sterling;

- Hong Kong dollar;

- Malaysian ringgit;

- Singapore dollar;

- South African rand;

- Taiwan dollar;

- Thai baht.

In addition, the domestic markets, but not the international markets, of the following currencies also use a 365‐day base:

- Australian dollar;

- Canadian dollar;

- Japanese yen;

- New Zealand dollar.

To convert an interest rate i quoted on a 365‐day basis to one quoted on a 360‐day basis (i*) we use the expressions given at (4.18):